Against Forgetting: Three Generations of Artists in Japan in Dialogue about the Legacies of World War II

Rebecca Jennison and Laura Hein

Although international consensus has it that the Japanese people are unusually reluctant to face their own wartime past, this generalization has never been entirely true, as regular readers of The Asia Pacific Journal already know. Like human beings everywhere, since 1945 Japanese have debated the lessons of war and disagreed about its meaning among themselves. And, also like people everywhere, many Japanese regret both official policies and widespread individual behaviors of the past. They not only desire reconciliation with Koreans, Chinese, and other Asians, but also recognize that, as Japanese, they cannot dictate its terms. Some have already entered into cross-national dialogue about the war and the colonial violence that reached its crescendo during the war years. Moreover, precisely because reflection on such issues is uncomfortable, they struggle over how to do so, often turning to oblique or refracted approaches, what Dora Apel calls “the sideways glance,” such as through literary or artistic expression.1 Both this ambivalence and these strategies are human rather than Japanese traits.

Visual artists, filmmakers, and fiction writers have far more experience expressing complex and contradictory emotions than do historians, so their prominent role in memory studies globally is not surprising.2 They show us how to convey the complex and sometimes messy individuality of actors. When we appreciate the ways that people are simultaneously well-meaning, bigoted, intelligent, obtuse, flawed, internally contradictory, and/or troubled human beings, it is easier to recognize the individuality of perpetrators, victims, and bystanders, while still acknowledging the actions that divided them as groups. Artistic work also directs our attention to the processes of imagination and to affective linking, explaining why some acts of historical imagination feel so much more satisfying than do others. Finally, identifying these contradictory qualities helps indicate a standpoint that can make reconciliation possible.

Of course, the style in which people imagine the past is not the same for everyone. One obvious difference is generational. While debates over war remembrance have reverberated through Japanese society at regular intervals ever since 1945, their nature is shifting as the generations of people who experienced the 1940s “join the great majority” that will one day claim us all.3 In many ways, 2010 served as a powerful symbolic reminder of that generational shift in Japan because so many significant twentieth-century events were commemorated— including the 100th anniversary of the annexation and colonization of the Korean Peninsula by Japan, the 55th year since World War II ended, the 60th anniversary of the beginning of the Korean War and the 10th anniversary of the 2000 International Women’s War Crimes Tribunal.4 In East Asia as elsewhere, the grey-haired individuals who testified to their direct personal experiences of war and colonial domination have had their say and now are yielding to people who have no choice but to make a larger imaginative leap in order to understand the wartime past.

Dialogue Across Generations: Individual memories, Postremembrance, and Imaginative Reconstruction

People who lived through the war in Japan need little prompting to remember how that era smelled, sounded, and felt, as one of us realized last year when an older friend casually mentioned that she would instantly recognize the sound of a B-29 plane overhead even though it had been decades since she heard one. These individuals also carry in their heads the internal logic of Japanese society in the 1940s. By contrast, the social ethos and institutional environment of the wartime era are so distant now that it is extremely hard to imagine twenty-somethings of today’s Japan conforming to its outmoded expectations. Young Japanese today—like young Americans—can barely fathom many elements of the wartime cognitive universe, such as its rigid class and gender hierarchies or the casual daily violence meted out within military ranks. They have no choice but to piece together isolated fragments of the past, using a variety of strategies to shape their images of the war years. And, while all generations interpret the historical events of the decades before their birth through assumptions that differ from those of their parents, such shifts are especially pronounced when social change is as momentous and as abrupt as it was for mid-twentieth century Japanese.

And what of the generation in between, particularly individuals born in the 1940s and 1950s? Although they do not remember the war, they still experienced it in a profound and distinctive–although indirect–manner as numerous memoirs and commentaries attest. Marianne Hirsch has written about the differences between acts of remembrance by people with first-generation experience of the war versus those of their children. She calls this second-generation experience “postmemory,” and also differentiates it from the preoccupations of historians or others interested in more far-flung outposts of the past. Difficult experiences–as World War II was for nearly everyone in East Asia–mark people in ways that profoundly affect their child-rearing practices.5 Her primary example, Art Spiegelman’s Maus: A Survivor’s Tale, brilliantly evokes the ways that Art’s parents’ harrowing experiences in occupied Poland and Auschwitz shaped his identity despite his far more comfortable childhood in New York City. In the opening pages of that memoir, young Art expects sympathy when some other kids roller-skate off without him. Instead, his father stops sawing a board: “Friends? Your friends? If you lock them together in a room with no food for a week then you could see what it is, friends!” Small wonder that Art feels compelled to understand the forces that shaped his father’s world view, or to express that quest artistically.6

Hirsch’s work has been very influential because it builds on Freudian theory about how individuals respond to trauma—through unconscious processes of repression and displacement. Properly speaking, “postmemory” refers only to a single generation: the people who pursue remembrance in order to make the baffling conditions of their own upbringing more comprehensible. Their personal histories include elements that are completely irreconcilable with the rest of their lives. The lives of postrememberers are indelibly marked “by traumatic events that can be neither understood nor recreated.” In her formulation, their response to that dilemma is “postmemory,” which is “a powerful and very particular form of memory precisely because its connection to its object or source is mediated not through recollection but through an imaginative investment and creation.”7 Hirsch actually waffles on whether “postmemory” can extend to a third generation, both in her book and a recent essay, but, either way, her contention is that family stories and photographs are the mechanisms by which people reframe the years before their birth as essential to their identities.8 Some of these effects may stretch beyond a single generation but they are surely most powerful for the children of the people directly traumatized. As she explains, “postmemorial work ….strives to reactivate and reembody more distant social/national and archival/cultural memorial structures by reinvesting them with resonant individual and familial forms of mediation and aesthetic expression.”9 Most valuably, she calls attention to the profound emotional investment in the past by people too young to remember it and explains why this occurs. Postrememberers feel an intense desire to make their own sense out of that past to address the profound cognitive dissonance created by growing up in the homes of people still responding to already-vanished events.

Hirsch, like other memory studies scholars, has struggled with how to expand this analysis to include remembrance by larger communities. It is particularly vexing when applied to people who did not personally experience the terrible event in question. While Freudian theory provides an elegant explanation for individuals’ engagement with the traumatic past, it is far less useful in showing how larger groups arrive at a common understanding of that past or how a second generation does. One way to handle that problem is to move to a more generic understanding of trauma, the strategy employed by Dora Apel, writing on “the art of secondary witnessing” of the holocaust, her term for second-generation remembrance through artistic expression.10 And perhaps doing so better captures the processes by which individuals as well as communities make sense of their world. Yet the work of scholars such as Hirsch and Cathy Caruth remains highly influential precisely because they ground it in Freudian theory.11

One way to retain their rigorous explanation for individual behavior while opening it out to become a social phenomenon is to treat postmemory, like memory itself, as a strategy that incorporates intergenerational dialogue—which functions as a kind of talk-therapy–as well as an internal psychological process. Depictions of the past frequently develop out of intergenerational dialogue, particularly as the event in question recedes in time. This is one reason why people so often only begin talking about the past openly and frequently a decade or more after an important event. Hirsch identifies family photographs and family stories as key to postremembrance but this misdirects attention to the talismanic object when the emotional power comes from the process of conveying historical knowledge, something that artists integrate into the making of new and intensely personal talismanic objects in the form of paintings, prints, collages, videos, and other art media. The members of the generation that remembers World War II across the globe have embarked on remembrance in large part to sway younger people out of a desire to make the war emotionally comprehensible to them. Often these older individuals were only moved to begin because earlier interactions revealed the cluelessness of young people. This is why, for example, the National World War II Memorial in Washington D.C. was only planned in the 1990s and completed in 2004.

Intergenerational dialogue is central to the remembrance of the next two generations as well, although in differing ways. Moreover, such dialogue is the precise point at which the fundamentally psychological familial relationship intersects with understandings of the past for a larger community, such as a nation. Indeed, while Apel’s main concern is with the problem of finding a way to represent the holocaust that does not “risk either a falsely manipulative and moralizing political instrumentalization or a depressing sense of obsession and despair,” the strategy she charts as a more successful form of representation actually incorporates intergenerational dialogue as a central aspect of the art work itself. As she points out, Art Spiegelman solved the problem of how to tell his parents’ story without being consumed by it by explicitly framing it as a dialogue with his father.12

Nearly all people under fifty years old today who engage the events of the 1940s are rather arbitrarily choosing to do so rather than seeking to manage powerful emotions that psychically cannot be ignored, the behavior Hirsch labels “postmemory” and identifies as crucial for Art Spiegelman. To be precise, individuals so far removed from the war may identify some stubbornly incompatible shards of the wartime past that linger in the present, and may also incorporate them into their creative expression, but these projects are indirect and idiosyncratic imaginative reconstructions of the past. Such individuals often are deliberately selecting specific elements of their heritage as important statements of identity while equally deliberately ignoring other elements. By definition, such a thoughtful and conscious process cannot be a Freudian response to trauma. Older people too, are contributing to a fundamentally public social process when they shape their message for younger generations, rather than “just” giving voice to a profound psychological trauma. But, as the strategies of artists described here suggest, their engagements with their audiences, often much younger than themselves, function simultaneously to bring their concerns onto the larger social stage and to partially resolve the internal conflict. And, while the art object itself may be arresting, it is the human engagement surrounding its production, dissemination, and display that operates as therapeutic treatment.

Artists who experienced the war

How then have artists and writers contributed to reimagining the war in Japan and how important is the intergenerational process? Quite a few, including most whose World War II remembrance are internationally famous, have not only challenged wartime priorities, but also have specifically sought to reach younger people. This group includes both the creator of the autobiographical manga (and film) Barefoot Gen, Nakazawa Keiji, (b. 1939) and Nosaka Akiyuki, (b. 1930) whose novel Grave of the Fireflies was made into a prize-winning animated film in 1988 by director Takahata Isao (b. 1935).13 These works shine a harsh light on the cruelty of both the wartime government and of many individual Japanese toward young children. Nakazawa also addressed the distinctive suffering of Korean colonial subjects in Japan, beginning in the early 1970s. Because these works are about the experience of children and are in visual form, both were immediately accessible to youngsters. Nakazawa began depicting the atomic bombing in manga form the day after attending his mother’s funeral, where he was shocked to discover that her bones had become so brittle due to her exposure to radiation a quarter-century earlier that nothing but ash remained after her cremation. Nakazawa’s wife was expecting their first child when his mother died, and both were troubled by the thought that she would never meet her grandchild. Sleepless over these personal sorrows, Nakazawa then moved beyond his own family story: “I thought and thought, and it always came to this: ‘Have the Japanese pursued and settled responsibility for the war?’ ‘Have the Japanese pursued and settled the issue of the atomic bomb?’ I realized that both issues had been rendered ambiguous, that neither had been settled.…I resolved to fight a one-man battle.”14

|

Cover of Richard Minear, Autobiography of Barefoot Gen |

Internationally recognized painters Maruki Iri (1901-1995) and Maruki Toshi (1912-2000) were impelled by the same impulse to convey the horrors they personally experienced in Hiroshima in 1945 and they too squarely addressed Japanese oppression of other Asians from the 1970s. Their work includes, for example, a large 1972 painting of crows flying past a Korean woman’s chima chogori dress, symbolizing the Koreans who were brought to Hiroshima to work in the local armaments factories and who perished in 1945.15 They chose the subjects of their later paintings by talking to visitors of all ages at their first exhibitions and responding to their comments and criticisms.16

This and other work is visible here.

Similarly, in 2006, contemporary artist Tomiyama Taeko expressed her frustration at failing to fully convey the savagery of Japan’s imperial policies to her compatriots. “I feel so sad and angry. What did we do? What did I do? It is difficult to create art that expresses any perspective other than ‘Japan is the victim.’ When I try to show how many Korean people suffered, it is seen as a Korean issue. Perhaps it is easier to express this through artwork than through literature because the visual medium can communicate directly. But it is hard to find places to show such work here in Japan.”17 Tomiyama, who is still painting at age 89, is one of the last artists of her generation to retain significant control over the ways that her expression is interpreted in public. She is keenly aware that few in her audiences today share her experiences and struggles to overcome this chasm, for example by avoiding interaction with professional art dealers and art critics and exhibiting where students congregate instead. Yet Tomiyama has enjoyed far more publicity in the last fifteen years than at any earlier time, suggesting that she has successfully connected to younger Japanese who approach the war only through “postmemory” or in even less intimate ways. Her first major exhibit in Tokyo was not until 1995, when Tama University Art Museum showed Silenced by History.18 Tomiyama’s signature theme is the moral obligation to remember the unnamed victims of war. She is currently hard at work, finishing a series of paintings about today’s war in Afghanistan, drawing on her own travels there in 1967 as well as more recent images of Afghanistan taken by photojournalists.19 She has also begun three large oil paintings in response to the March 2011 earthquake, tsunami, and ongoing nuclear disaster in Fukushima, connecting the past to the present in new ways.

|

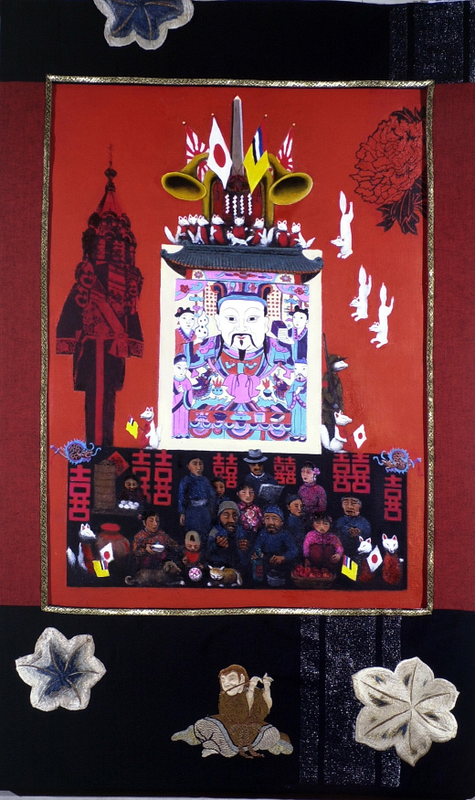

Tomiyama Taeko, Foundation of Manchukuo, painting from “Harbin: Requiem for the 20th Century,” 1995 |

The work of artists of Tomiyama’s generation is now nearly all mediated by younger museum curators, gallery owners, and art historians, who are making such art more visible, both in Japan and abroad. This group includes such “postrememberers” as museum curators Kobayashi Hiromichi at the Tama Art University Museum and Mizusawa Tamotsu at the Kamakura Museum of Modern Art. Kobayashi has also played a central role as photographer and collaborator in the production of Tomiyama Taeko’s slide and DVD works; in effect he is transmitting the artist’s ideas through new media, while developing his own “postrememberer’s” representational strategies in innovative sites of expression, further illustrating our point that these two generations work in dialogue with each other in many kinds of ways.20

Both Kobayashi and Mizusawa also have recently displayed works by Miyazaki Shin, another artist whose work is infused with his wartime memories. Like Tomiyama, Miyazaki is far better known in the 21st than he was in the 20th century. Miyazaki, born in 1922, is no longer an active artist.21 He grew up in Yamaguchi prefecture, graduated from art school in 1942 and was drafted a few months later. His unit was dispatched to northeast Manchuria and, when the Kwantung army disintegrated in August 1945, Miyazaki at first was stranded there without food, and then was taken prisoner and transported to Siberia, returning home only in 1949. He resumed painting but did not then depict his wartime experiences. In 1965, Miyazaki not only enjoyed his first exhibition but also won the Nitten Exhibition Prize for one of his paintings, “Night of the Festival” (Matsuri no Yoru). Two years later, Miyazaki’s canvas “Sideshow Performers” (Misemono Geinin) won the prestigious Yasui Sōtarō Memorial Prize. Miyazaki began teaching painting at Tama University in 1981, at age 59, and his career really only took off when he was in his sixties, after his personal experiences of the 1940s became the main topic of his work. He won a prize in 1984 for “Winter Light” (Fuyu no Hikari), and had a major exhibit of his work at Tama Art University Museum in 1992. In 1999 the Yamaguchi prefectural art museum displayed the first of his monumental paintings about Siberia, some of which were also shown at the Kamakura museum in 2001. Mizusawa, the curator in Kamakura, also commissioned two canvasses from Miyazaki for the Sao Paulo Biennale of 2004, and Miyazaki chose to depict in abstract form the miserable weeks just after Japan’s surrender. His work is visible on his official website here.

Miyazaki’s large, dark, densely textured canvasses have a potent impact for viewers but reproduce poorly. Like Tomiyama, Miyazaki is primarily concerned with giving expression to the feelings of powerless people, whose suffering is of no concern to others. He includes his former self in that group more than does Tomiyama, but never frames his experience as a national Japanese one. Nor does his work convey bitterness at his captors. Rather, it emphasizes loss, abandonment, the fragility and value of human life, and, most importantly, the intensity of his own feelings about the past. Miyazaki explains that, like Tomiyama, he is motivated in part by his horror that younger people have not yet learned to avoid war. While he struggles to articulate his tangled emotions about his personal experiences, Miyazaki is crystal-clear that he embarked upon that struggle “because we have once again entered a period of warfare.”22 His insistent demand for our attention helps explain why sustained direct interaction with survivors is such a powerful phenomenon.

Indeed, postrememberers not only receive these messages, they actively solicit and help shape them through their interactions with the older artists. Mizusawa describes Miyazaki’s work as follows: “When we experience a work by Shin Miyazaki, we are first of all overwhelmed by the silent voices that emanate from the physical object that is the artwork, regardless of its size or medium.….We hear, too, intermixed, the voices of others, for in his works the artist has committed his prayers for the eternal repose of their souls.”23 Mizusawa explains that he said this to Miyazaki in 2003 and that the artist, then 82 years old, responded to his comments by producing five huge canvases in six months rather than just the two Mizusawa had requested. One of these was “Mud,” a work that Mizusawa describes as at first seeming to signal “bottomless despair,” but, after more extended viewing, reveals “a place of surging energy that is not entirely negative.” Mizusawa, the “postrememberer,” expresses his own stance to wartime society as well as to the artwork when he explains that “these paintings present unstable, incomplete situations and fail to provide a port of refuge for the viewer’s emotions.” That emotional state, in turn, “arouses numerous memories and cannot be compressed within individual experience.”24 Message received indeed.25

Postrememberer Shimada Yoshiko

The postmemory generation includes not only curators and art historians but also artists such as Shimada Yoshiko. Shimada, born in 1959, was raised in the shadows of the U.S. Air Force Base in Tachikawa near Tokyo, formerly used by the Imperial Japanese Army. After attending university in the United States, she spent time in Berlin, where she viewed the work of artists engaging directly with the question of German war responsibility. Later, she lived in New York at the time of the first Gulf War, and saw artists dissent through their art. Comfortable in English and German, Shimada has built a transnational platform for herself, meaning that her reflections on her country of birth are informed by deep knowledge about war experience and war remembrance elsewhere. On visits to Japan in the early 1990s she was angered by the nostalgic portrayals of Japan’s war and the Shōwa Emperor, who had passed away in 1989, and so began her artistic reflection on the wartime past. In her series “Past Imperfect,” she both challenged the simplistic view that the war was an unavoidable tragedy and tied that theme to her longstanding interest in gender.

|

Shimada Yoshiko, “White Aprons” from the series “Past Imperfect” 1992 |

“Past Imperfect” explored the extent to which Japanese women had participated in and strengthened the war effort—and the costs of that collaboration to themselves, to other Japanese women, and most of all to Asian women. She chose as her symbol for their enthusiasm the white aprons, or kappogi, that wartime Japanese patriotic women’s organizations had adopted. Using old photographs of these mothers holding smiling babies, waving flags, and lighting the cigarettes of soldiers, she created collages that commented on their choices. Her critique was made sharper by the border around one of these collages, which incorporated photos of young “military comfort women.” As she explained, “I realized that Japanese women were not entirely the voiceless victims of male-dominant militarism. Many were enthusiastic fascists and willing to sacrifice themselves and to victimize others in the name of the emperor.”26 This project emphasized the ways that wartime Japanese women were drawn into the conflict as mothers of soldiers, a form of recognition that simultaneously celebrated them and severely limited their life choices, while also noting that Asian women were assigned far harsher tasks.

In this early work, Shimada seems to be distancing herself from the wartime generation’s self-serving romanticized remembrance but as time went on, she challenged herself and other postrememberers to acknowledge their own responsibility for the past, despite being born after the war. Indeed, the impetus for “Past Imperfect” came from Shimada’s recognition that she shared some of the qualities that had led so many wartime Japanese to accept the need for millions of pointless deaths. As Shimada put it, “Personally, I basically like absolute discipline, and tend to be swayed by emotion rather than logic and so I suppose it would be quite simple for me to become a fascist.”27 And, even more fundamentally, she doubts that anyone ever can be completely confident of the morality of their own behavior within a repressive society. As she put it, “when I talk about art and activism, I do not make art from the viewpoint of the oppressed or the victimized. I make art to make the oppressors think of what they do from where they are. But there is no clear borderline between the oppressors and the oppressed anymore.”28 Shimada feels a responsibility to revisit the war precisely because she did not herself experience it and so cannot be confident that she would have behaved ethically.

Shimada’s 1995 work, “Comfort Women/Women of Conformity,” expanded on the images of military comfort women that had first appeared in “Past Imperfect” by including photographs of the aged survivors and snippets of their testimonies in installation works.29 She juxtaposed them with startlingly racist eugenicist comments by famous presurrender feminists such as Hiratsuka Raichō, pointing out the racial boundaries of Hiratsuka’s imagination. If earlier feminists had combined acute gender analysis with such an absence of empathy for Asian women, how can feminists today be sure they are not replicating that pattern?

|

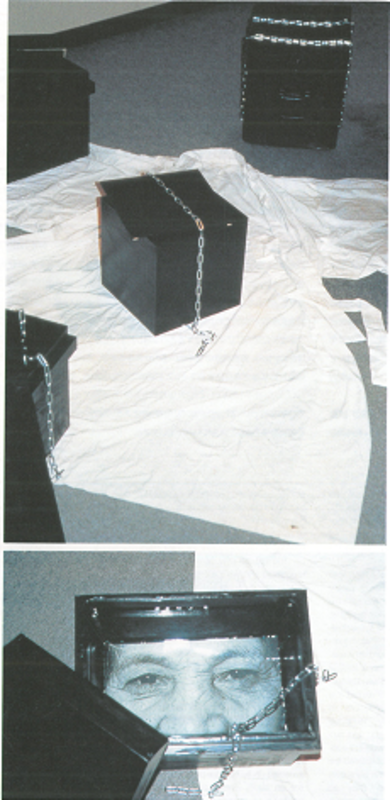

Shimada Yoshiko, image from “Black Boxes + Voice Recorder” 1996 |

Shimada’s willingness to ask herself “would I have behaved differently?” became more evident in a major exhibit at the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography in 1996. Shimada’s installation piece, “Black Boxes + Voice Recorder,” featured photographs of former “military comfort women” exhibited in chained black wooden boxes. Placed on the floor of the gallery with “lids off,” the boxes contained the portraits of the women submerged under several inches of water. Meanwhile, recordings of the women’s voices giving testimony about their wartime experiences played continuously. Shimada’s aim was to create a space in the museum for these testimonies, as well as to encourage visitors to investigate the “internal conditions” of wartime Japanese society that allowed such callous exploitation of poor Asian women. As she saw it, fully appreciating the harm inflicted on them required looking critically at the actions of Japanese women during the war and also acknowledging the ways in which Japanese men’s “humanity had been violated” under the military regime. Shimada encouraged viewers to feel empathy for the people most victimized but also to acknowledge that the worst perpetrators were trapped in a fascist system that did not protect their best interests either. Curator Kasahara Michiko wrote that Shimada’s work “represents a resistance to forgetfulness, an active will to remember. She is not an outsider, producing her work in some safe place; rather, as a Japanese woman she is placed in the ambiguous place of being one of the assailants.” And, Kasahara continues, Shimada’s labor is necessary, “or we will never be free of the nightmare of war.”30

It seems that Shimada could only fully express her discomfort with the values of wartime Japan when she imaginatively entered that past society rather than merely viewing it from a distance, suggesting that successful remembrance—as opposed to postremembrance–may require a kind of double vision that includes empathy for all involved. In other words, rather than unconscious displacement to manage trauma, it requires not only conscious acknowledgement of the pain felt by others but also an imaginative acceptance of responsibility for that pain. In other exhibitions in the early 1990s, Shimada included a live-art performance in which she herself appeared wearing the symbolic white apron, which also became the screen for projected images of the former “military comfort” women.31 Her work is effective because it encompasses both a sympathetic understanding of the weaknesses of wartime actors and a firm rejection of the values on which their actions were based, achieving a genuine dialogue with the past. As Kasahara explained, Shimada and the other artists in the 1996 exhibit “have the will to question the very basis of their way of thinking… to look at things from a view opposite to that of their own perspective and reconstruct the way they think.” Kasahara argues that feminism provided Shimada with the sense that “we Japanese, alive today, have a duty not to erase, but to preserve and pass on to future generations….the numerous crimes that were committed by the Japanese during the Second World War.”32 In the same volume, Ōgoshi Aiko draws an even stronger connection between feminism and an anti-war stance, arguing that “the threat of war lies at the root of the genderization of authority, that this is what led to the acceptance of the structure of sexual prejudice and violence, even in peacetime.”33 The question to the older generation in this implied dialogue is less about “what happened” than it is about “how did you let it happen?”

We note that here too we see intergenerational dialogue. Shimada’s choice of the military comfort women as her theme was triggered by the testimonies of Kim Haksun and other former “comfort women.” Shimada was also familiar with Tomiyama’s series of 1988 on the same subject, while Tomiyama incorporated the white apron (stylishly worn by lady foxes in her rendition) into her 1995 series “Harbin: Requiem for the 20Th Century” and “The Fox Story” of 1999. The DVD version of “The Fox Story” also featured photographs of the young comfort women, suggesting an intertextuality that moved in both directions. Both artists evoke the lost world of the past in order to warn viewers against the self-deluding character of nostalgia, and both rely on feminism as a moral guide through the past. Shimada’s critique also was powerful enough to impress “Resident Korean” artist and activist Hwangbo Kangja (b. 1957), who had already spent several years giving lectures and producing documentaries about the military comfort women. Hwangbo met Shimada through this show and invited her to collaborate on a joint exhibit based on family photographs, which was displayed in Vancouver and Gwangju.34 That project became an opportunity to work out more fully Shimada’s own relationship to war remembrance.

In this exhibit and in a later project, Shimada focused on the personal experiences of her own relatives, adopting the strategy identified by Hirsch as characteristic of postrememberers. Like Art Spiegelman, Shimada suggests that the secrets of the past resemble a locked box that retains its power as long as she carries it forward unopened, also explaining her chained black boxes of 1996. But, unlike Spiegelman, she is less interested in the inter-generational effects of traumatic war experience on herself than in the ways that keeping secrets has protected her from understanding the harm she and her family may have done to others. Indeed, while researching her family history for this project, Shimada uncovered part of her own family’s past: her grandfather, who had worked as a policeman before the war, was ordered by his superior to “dispose of dangerous criminals” in the aftermath of the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923. This was not an isolated case. Vigilante groups and police responded to rumors that Koreans were causing mayhem by murdering as many as 6,000 individuals in the wake of the earthquake.35 Shimada herself recalled that her grandfather never allowed them to make a “snapping” sound with wet towels because it reminded him of the sound of Korean victims’ skulls being struck with wooden bats. (Later, Shimada’s grandfather quit the police force to become a farmer. According to her mother, he also helped Korean conscripted laborers escape during the war.) This is precisely the kind of childhood experience that makes the case for retaining the psychological concept of “postmemory,” now expanded to include coping with the memories of perpetrators as well as victims, while examining how it becomes a broader socially relevant experience. For Shimada working through “postmemory” necessarily means refusing to evade responsibility and making amends by openly acknowledging her own connections to this past.

|

Shimada Yoshiko, Copenhagen installation of “Bones in Tansu: Family Secrets” 2004 |

That disturbing discovery led to Shimada’s next project, Bones in Tansu: Family Secrets, an ‘interactive’ installation piece that was first exhibited at A.R.T in Tokyo in 2004 and then in seven other locations internationally.36 Shimada began by exploring the boundary markers between her own private memories and public remembrance, and over the next three years solicited the anonymous personal memories of gallery viewers, which she incorporated into the exhibit. Once again, she began with family histories, although this time with memories generated by strangers, to make visible the emotions evoked by the past. This ever-expanding dialogue revealed much trauma, sometimes linked to war histories, but most often to an unexpectedly high incidence of domestic violence, including incest and sexual abuse. These traumatic stories crossed national lines. For example, participants in Manila wrote about the experience of being abused as children in response to a similar “secret” revealed by a Korean participant at the previous site. Some of the Manila children were vulnerable to predatory adults because their parents had been forced by poverty to become global migrant workers, revealing another way in which “private” family trauma is part of transnational history.37 Shimada is facilitating an open-ended dialogue among visitors that makes no assumptions in advance about who may be a victim or a perpetrator, while unequivocally condemning transgressions by making visible the pain they caused.

The Next Generation

What aspects of the wartime past matter most to younger people in Japan who wish to take a stance “against forgetting” World War II? Their engagement with the war seems to begin with their recognition that they know little about the lives of the older individuals who peopled their childhood and grow into a nagging feeling that such ignorance is a debt that requires redress, meaning that a desire for more intergenerational dialogue is at the heart of their quests. It seems likely that, as with the older artists, their interactions with historians, art historians and curators—as well as larger audiences—will continue to shape their inquiries into the past, as will transnational dialogues with other artists and social-justice activists. Eventually, so will their interactions with people younger than themselves.

One recent collaborative project arrayed “against forgetting,” Asia, Politics, and Art, is itself a transnational venture that brought together artists, musicians, scholars, and curators of various ages to explore the legacies in East Asia of World War II, the Korean War, the Vietnam War, and the current American-led wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Lee Chongwha of Seikei University organized this project on the “lingering wounds” of past wars in order to develop new kinds of dialogue for the future. Their efforts between 2006 and 2008 led to a unique collaborative publication, Zanshō no Oto (Sounds of lingering wounds).38 Their work is also in dialogue with deceased artists, as is symbolized by the fact that the inaugural conference for Asia, Politics and Art was held in the Sakima Art Museum in Ginowan, Okinawa in March 2007, in a room whose walls are covered with the enormous panels of the “Battle of Okinawa,” by Maruki Iri and Toshi.39 (Link)

Oh/Okamura Haji (b. 1976, hereafter Oh Haji) and Yamashiro Chikako (b. 1976), both of whom participated in this project, are two generations removed from direct experience of the war but explore its meaning today in their work. Not only are they far younger than Tomiyama and Miyazaki, their respective positions as a “Resident Korean” and an Okinawan complicate their status in relation to Japan. Both artists, still at formative stages in their careers, evoke the wartime era in their work, in ways that emphasize their temporal distance from the 1940s and underline their postwar identities. Interestingly, they also use some of the “postmemory” techniques discussed by Hirsch and explored artistically by Shimada, such as creating an imaginative world from the fragmentary images provided by old photographs and objects used by their relatives, and building out from the testimony of older family members and neighbors about past experiences.

Oh Haji uses a variety of spinning, weaving and dyeing techniques to create original garments, objects, and installations that give material expression to the layering of time and memory.40 The death of her Korean-born grandmother prompted the artist to explore themes of personal history and memory in greater depth. Although she had shared a home with her grandmother all her life, since Oh spoke only Japanese and her grandmother was only comfortable in Korean, they had never communicated easily. Her regret at not having worked harder to overcome the painful silences between them prompted Oh to imaginatively recall her grandmother’s life in a large, mixed-media installation piece, “Memory” (2006). “Memory” recalls Oh’s grandmother’s forced prewar move from her original home on Cheju Island in Korea to Osaka. Oh painstakingly covered a semi-sheer white cloth with a flower pattern like those on skirts worn by her grandmother. For Oh, clothing, like family photographs, provides a physical object that can bear the weight of the tasks of creating an imaginative investment and framing identity, and so—at least partially—replace the emotional satisfaction derived from communication through language.

|

Oh Haji, Image from “Memory” 2006 |

Oh had previously used thread that she had carefully unraveled from her grandmother’s Korean dresses in other projects, and later decided to photograph her Korean chima blouse, which she had hung on the wall of her room. Oh said that interacting in such ways with her grandmother’s clothing helped her “feel as if she were really there, as if she was ‘physically present.’ That was the inspiration for this work.” Knowing little of her grandmother’s thoughts and feelings, Oh hoped to gain an imaginative understanding of her life experience by making art from the clothing she left behind after her death. While they shared the label of being Korean in Japan, they shared little else until Oh decided to learn more about the older woman’s life. Oh acknowledges in her art that she moves through Japanese society with far more linguistic and cultural ease than did her grandmother and was offering redress—literally re-clothing—for her own youthful obliviousness to her grandmother’s linguistic isolation. Her forthright acknowledgement of her own complicity in that isolation and her feelings of regret give her work its power, as does the intensity of her desire to capture as much meaning as she can from the threadbare swatches of her grandmother’s garments.

Yamashiro Chikako, an Okinawan video and performance artist, has also begun exploring remembrance of the war in recent highly innovative video works that, like Oh, imaginatively place her in an ambiguous ethical relationship with elderly victims of war and colonial violence.41 Yamashiro became interested in this topic after June 2007 when the Japanese government eliminated passages from history textbooks that made reference to the “mass suicides” in the Battle of Okinawa. In the last weeks of the war the Japanese military had encouraged and sometimes ordered Okinawan civilians to kill their families and themselves in order to avoid capture by the advancing American forces. The subsequent protests against the textbook changes (Link) prompted Yamashiro to interview senior residents in a nearby care center in Okinawa on video, which she then transformed into works she exhibited at two Tokyo museums, the National Museum of Modern Art and the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography in 2009 and 2010. In a statement describing “Your Voice Came Out Through My Throat” (2009), the artist explains that many of the elderly people had never spoken of their wartime experiences. Like Yamashiro, however, they were so offended by the government’s move to revise textbooks that they told their stories to her. She extended this theme in a 2010 series, “Sinking Voices, Red Breath.”

|

Yamashiro Chikako, still image from video “Sinking Voices, Red Breath” 2010 |

They also passed on their feelings of responsibility for remembering the past, telling Yamashiro, someone of their grandchildrens’ generation, “because we survived you were born into this world. And now 65 years have passed since the war ended, we have to tell what really happened.”42 Yamashiro said she could feel the exact moment when each speaker transferred the burden of remembering the past to her in an interview with Kum Soni, another participant in the Asia, Politics, and Art project.

When talking about the war there was a moment when the elderly people would stop speaking. Perhaps, it was the instant that brought back what was most painful, most devastating in the minds of the speakers. At those moments, when they were about to speak about the most painful things, they fell silent, and began to shake or weep. …so then I just asked them to touch me and express what they were feeling in some other way.”43

In January and February 2011, Yamashiro participated in an artists’ exchange and festival in the Philippines, and began doing research for new work based on oral histories and memories of Okinawan migrants and war-brides who moved there during and after the war. She wanted to showcase Okinawan responses to the ongoing presence of US military bases in Okinawa, and also make a connection between that situation today and Okinawan participation in the Japanese military occupation of the Philippines in the 1940s. This experience will add greater moral ambiguity to her already-arresting photographs and video works. It will also add a transnational dimension to her intergenerational commentary.

These young artists are gathering fragments of the war experience and are connecting them to their own postwar stories in ways that both require intergenerational dialogue and encourage it in others. While they are clearly motivated by their sense of shared identity with specific groups of people who were systematically wronged during the war, they are not drawing a stark distinction between the descendents of victims and of perpetrators or bystanders, nor absolving themselves of responsibility. Finding a stance that expresses recognition of their own distance from the wartime victims while sympathetically acknowledging the injustice of their victimization is crucial to powerful imaginative reconstruction. This distance can be as little as the passage of time in an individual life, as with Miyazaki Shin, or it can involve soliciting the views of people who previously seemed of little interest, as with Yamashiro Chikako. What is being bridged here is the gap between postremembrance as displaced attempts at psychological healing by traumatized individuals and conscious social acts based on interaction with older or younger people.

Why do these acts matter? Acknowledgement by young people and bystanders as well as by perpetrators that victims’ suffering was not only very real but also unjustly imposed is a form of redress. This is why people feel such deep satisfaction when their own experiences are belatedly acknowledged to be of public importance, i.e., part of history. In the end, providing that sense of satisfaction to their elders is a major way that young people make the experiences of earlier generations part of their own lives. Much of the time these transactions happen invisibly around holiday dinner tables or in everyday public settings, such as classrooms. These artists are finding ways to initiate dialogue, which, rather than the art work itself, becomes a talk-therapy for themselves and frequently for others as well. The Marukis, Nakazawa, and Miyazaki all report that they were unable to express themselves on other topics until they painted or drew the war, while Shimada visited the past because she wondered how she would have behaved then—and was honest enough to admit doubts that her choices would have been ethical ones. Oh and Yamashiro both stumbled into their projects for reasons that they could only articulate after paying close attention to the older generation for the first time. Sometimes the impetus is the emotional desperation at the heart of Hirsch’s remembrance/postremembrance while others begin to care about unacknowledged war-related traumas through more cerebral processes. Both paths lead to the same result: they remind us with admirable clarity and poetic subtlety that all of us today bear responsibility for redressing the injustices of the war. And without such redress, it is very difficult to create a future that truly moves beyond the injustices of the past.

Rebecca Jennison is a professor at Kyoto Seika University in the Department of Humanities, Division of Culture and Arts, and an Asia Pacific Journal. She is active in a variety of feminist and peace networks. She recently curated with Fran Lloyd (Kingston University London) The Art of Intervention Now – London & Kyoto 介入の芸術、現在(いま)〜ロンドン&京都 at the Fleur Gallery, Kyoto Seika University (24th September – 23rd October 2010). (Link) Her most recent publications include an essay in Zanshō no Oto, Iwanami Shoten, Tokyo.(2009)『残照の音―アジア・政治・アートの未来へ』岩波書店、2009) and, with Laura Hein, Imagination Without Borders: Feminist Artist Tomiyama Taeko and Social Responsibility, Ann Arbor: Center for Japanese Studies, The University of Michigan, 2010.

Laura Hein is a professor of Japanese history at Northwestern University in Chicago and an Asia Pacific Journal coordinator. Her most recent publications, in addition to the book edited with Rebecca Jennison mentioned above and its companion website, include “Reckoning with War in the Museum: Hijikata Teiichi at the Kamakura Museum of Modern Art” Critical Asian Studies, 43.1 Winter 2011, pp. 93-110 and “Japan, the Vulnerable, and All of Us” foreword to Dreams of Repair, Eleanor Rubin Milan: Charta, 2010.

Recommended citation: Rebecca Jennison and Laura Hein, “Against Forgetting: Three Generations of Artists in Japan in Dialogue about the Legacies of World War II,” The Asia-Pacific Journal Vol 9, Issue 30 No 1, July 25, 2011.

Article on related subjects

Andrea Germer, Visual Propaganda in Wartime East Asia – The Case of Natori Yōnosuke

Sumida Local Culture Resource Center, That Unforgettable Day–The Great Tokyo Air Raid through Drawings あの日を忘れない・描かれた東京大空襲

Asato Ikeda, Twentieth Century Japanese Art and the Wartime State: Reassessing the Art of Ogawara Shū and Fujita Tsuguharu

Yuki Tanaka, War and Peace in the Art of Tezuka Osamu: The humanism of his epic manga

Nobuko Tanaka and Laura Hein, Brushing With Authority: The Life and Art of Tomiyama Taeko

Ishikawa Yoshimi, Healing Old Wounds with Manga Diplomacy. Japan’s Wartime Manga Displayed at China’s Nanjing Massacre Memorial Museum

elin O’hara slavick, Hiroshima: A Visual Record

Notes

1 Dora Apel. Memory Effects: The Holocaust and the Art of Secondary Witnessing. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press. 2002, p. 3.