China-Korea Culture Wars and National Myths: TV Dramas as Battleground

Robert Y. Eng

China and Korea have been engaged in a culture war in recent years, contesting issues of national identity, historical territorial claims, and cultural heritage. The single most inflammatory topic in this culture war is conflicting interpretations of the history of Goguryeo (Koguryo 高句麗) (37 BCE-668 CE), which ruled large areas in present-day Northeast China and Northern Korea, and constituted one of the Three Kingdoms in Korean history, along with Baekje (Paekche 百濟) (18 BCE – 660 CE) and Silla (新羅) (57 BCE – 935 CE) (Figs. 1 and 2).1 North and South Koreans consider Goguryeo to be a key foundation state of their history. They are therefore angered by Chinese claims that the “various tribes that inhabited Koguryo [were] … among the many minorities that were eventually absorbed into “Greater China,” and therefore “its history is considered a part of Chinese national history.”2

North and South Koreans regard this view of Goguryeo as a Chinese state, advanced through research by the government-sponsored Northeast Project,3 as a usurpation of their national history. South Korean scholars have criticized The Northeast Project as a politically motivated historical distortion that “has been designed to prove that the Northeast area, including areas in which Koguryo, Old Choson, Puyo, Parhae and even modern Korea were or are situated, were historically and culturally a part of China.”4 South Korean Foreign Minister Ban Ki-moon (now the United Nations Secretary-General) stated in 2004: “It is an indisputable historical fact that Koguryo is the root of the Korean nation and an inseparable part of our history … We will sternly and confidently deal with any claims or arguments harming the legitimacy of our rights.”5

As the history wars threatened to escalate into a diplomatic crisis, both China and South Korea, which have much to gain from political cooperation and economic ties, reached an agreement in August 2004 “to refrain from waging “history wars” and leave the arguments to the historians.” Foreign Minister Ban announced that a five-point verbal understanding had been reached: “China said it was mindful of the fact that the Koguryo issue has emerged as a serious problem between the two nations. Both sides shared the view that this historical issue should not undermine bilateral relations.”6

The issue, however, remains far from resolved. Festering anger among Koreans towards the Chinese in connection with the Goguryeo dispute and other related problems7 has chilled formerly warm feelings towards China.8 The Chinese, on their part, have been rankled by what they view as Korean actions “brazenly encroaching on China’s cultural heritage.”9

Fig. 3: The Stele of King Gwanggaeto of Goguryeo, erected 414 CE, Ji’an, China |

Behind this culture war are the use and the misuse of history and culture in support of contemporary nationalistic sensibilities and political agendas. Ethno-nationalism is primarily directed internally for nations such as China that have a mixed ethnic composition, but externally for nations such as Korea that have a relatively homogeneous population.10

History in the Service of Chinese and Korean Nationalist Agendas

The problem of incorporating non-Han minorities into a modern Chinese nation-state has preoccupied Chinese governments since the fall of the Qing Dynasty in 1911. Should China adopt a federal system in which non-Chinese peoples enjoy complete sovereignty and even the right to secede? Or should China resort to compulsory assimilation of the non-Chinese peoples in order to create a single unified citizenry? In the end, the People’s Republic of China rejected both open federalism and compulsory assimilation, and adopted instead a middle way: a “unified multi-national state” (统一的多民族国家) with the Han majority (汉族) and 55 “minority nationalities” (少数民族) officially recognized since the 1950s.11

The Chinese state mobilizes history to support this theory of a “multi-cultural unity of the Chinese nation,” according to which “all ethnic societies that existed or exist within modern Chinese territory [including Goguryeo] played a role in forming the historical community of China to some degree. Thus, they are all Chinese nations, and the dynasties established by the Mongols, Manchus and others become Chinese. This includes the claim that the territory ruled by each dynasty constituted Chinese territory.”12 This historical narrative legitimates a unified nation composed of many nationalities (minzu).

For South Korea, a much more homogenous society in ethnic terms, on the other hand, the goal of national reunification is paramount. A historical narrative of the longevity, continuity and distinctiveness of a Korean nation pitted against dangerous external enemies supports this goal of national reunification.13 Thus, in both China and Korea, modern political sensibilities and conceptions of the nation as a community are being projected back in time in support of respective nation-building agendas.

Fig. 4: The Goguryeo General’s Tomb, Ji’an, China |

The construction and propagation of a national historical narrative thus serve the political needs of the present, and constitute an enterprise in which both state and society participate. History and archaeology provide the arenas for this communal project as played out not only in academia and the classroom,14 but also, importantly, in the media and in cyberspace. Television, as the preeminent traditional medium of news and entertainment with the greatest reach, plays an important role.

State Building and National Identity Formation in Chinese and Korean Television Dramas

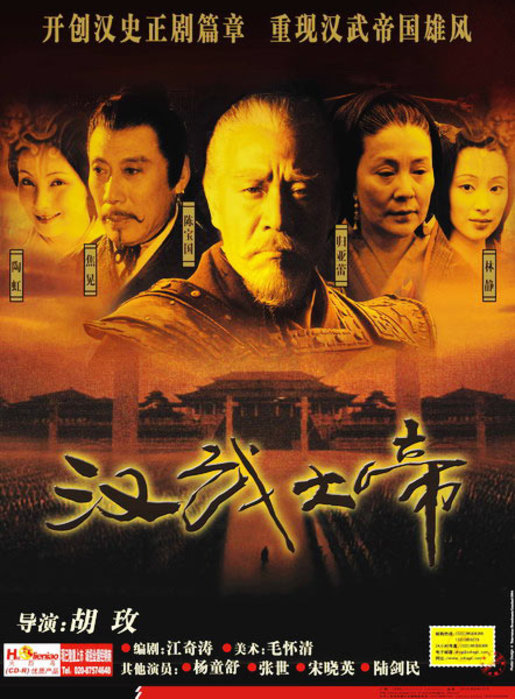

This article offers a comparative analysis of the discourse on state building and national identity formation in historical television serials in China and South Korea. I assess The Great Han Emperor Wu (Han Wu Da Di 汉武大帝) (2005) and Jumong (2007) in light of contemporary nationalistic sensibilities. The dramas portray the struggles of two rulers who confronted external and internal enemies to national unification and territorial expansion: Liu Che (劉徹) who became Emperor Wu (漢武帝) (156 – 87 BCE; r. 141 – 87 BCE) and consolidated the Han Dynasty, and Jumong (朱蒙) (58 – 19 BCE, r. 37 – 19 BCE), founder of Goguryeo (高句麗). It was during the reign of Emperor Wu when the Han Dynasty extinguished the state of Gojoseon (古朝鮮) or Ancient Joseon (Choson) and set up four commanderies in what is today Northeast China and the Northern Korean peninsula in 108 BCE: Lelang (樂浪; Korean: Nangnang), Lintun (臨屯; Korean: Imdun), Xuantu (玄菟; Korean: Hyeondo), and Zhenfan (真番; Korean: Jinbeon). Fifty years after the death of Emperor Wu, Jumong established the state of Goguryeo.

Fig. 5: Goguryeo Tomb Mural: Hunting scene, Ji’an, China |

Both The Great Han Emperor Wu and Jumong were lavish productions that attracted huge audiences and triggered a plethora of responses. The Great Han Emperor Wu (Fig. 3), a production of China Central Television (中国中央电视台) (CCTV), premiered on January 2, 2005. It set the record for advertising revenues for a CCTV drama series.15 Reportedly the most expensive television series ever made in China at a cost of 50 million yuan or US$ 6 million, The Great Han Emperor Wu portrays more than 1,700 characters in its 58 episodes.16 Director Hu Mei (胡玫) had directed the enormously popular 1997-1998 television serial on the Yongzheng Emperor in the Qing Dynasty, Yongzheng Dynasty (Yongzheng Wangchao 雍正王朝). Both Yongzheng Dynasty and The Great Han Emperor Wu fall into the category of palace dramas that have been popular since the mid-1990s. Unlike the historical serials of the 1980s, which “focused on the cultural corruption and cultural decline of the late Qing,” the later palace dramas celebrated national unity and prosperity during such pinnacles of imperial history as the Qing in the 18th century.17 To Chinese audiences, these historical serials offer political allegories for the present, a time when China is enjoying extraordinary economic growth and a growing international profile, but is also experiencing problems of political corruption, social inequities and ethnic tensions as well as territorial and other international conflicts.

Jumong (Fig. 4), a production of Munhwa Broadcasting Company (MBC), one of South Korea’s four big broadcast networks, premiered on May 15, 2006, and concluded its run on March 6, 2007. It garnered an overall rating of 50.3%, becoming the 5th highest rated historical drama and the longest-running no. 1 show with 81 episodes in Korean television history.18

Fig. 6: Poster for The Great Han Emperor Wu (2005): from left to right, master spy Liu Ling, Emperor Jing, Emperor Wu, his grandmother Empress Dowager Dou, and his consort Wei Zhifu |

Differing Milieux for TV Productions in China and Korea

The two television serials, however, were produced and broadcast in very different political, cultural and economic milieux. While the Chinese media market has become much more liberalized than before the start of economic reform in 1978, it remained under the close scrutiny of the Communist party-state. The State Administration of Radio, Film, and Television (国家广播电影电视总局),19 or SARFT, regulates media content and directly controls state media enterprises at the national level, including China Central Television or CCTV. Movie and television scripts must be submitted to SARFT for approval. Scripts that are deemed to be deleterious to public morality, social harmony and national dignity may be rejected or have revisions mandated. SARFT sets quotas on domestic television productions by genre and the quantity of foreign imports, in accordance with changes in government cultural policy.20 Both SARFT and its counterpart for monitoring print publications, the General Administration of Press and Publication (GAPP), must coordinate with the Communist Party’s Central Propaganda Department (CPD) “to make sure content promotes and remains consistent with party doctrine.”21

Even after a television drama has passed the end product review by SARFT or its local affiliated bureau, received a distribution license, and has begun to be screened on air, it may still be pulled off or subject to major revisions if it incurs the wrath of a major political leader.22 One important example is the 2003 CCTV production Marching Toward the Republic (走向共和), which aroused considerable controversy and debate over its revisionist reinterpretations of historical personalities during the last two decades of the Qing Dynasty. Some episodes suffered cuts by censors during its initial broadcast. Then plans for rebroadcasting the series were vetoed by the government. There was a lot of speculation on why the series was banned. Was it because the series promoted the idea of democracy? Or did it offend retired President Jiang Zemin who thought that he was being compared to Empress Dowager Cixi “reigning behind the curtain”? Or was it current President Hu Jintao who ordered the plug pulled because he thought the powerless “Boy Emperor” Guangxu was a stand in for him?23

Fig. 7: Poster for Jumong (2007): from left to right, Jumong, his love and political ally Soseono, his adoptive father King Geumwa, his mother Lady Yuhwa, and his rival Prince Daeso |

In comparison, government regulation of the Korean media market is more relaxed. The end of military rule and the beginning of the democratization of South Korea in 1987 brought much greater freedom of expression to Korean media. Until the passage of the new Broadcast Law by the National Assembly in December of 1999, the Ministry of Information and Communication and the Ministry of Culture and Tourism, as well as the Korean Broadcasting Commission (KBC) and the Korean Cable Communications Commission (KCCC) shared regulation of television broadcasting. Since 2000, regulation of all types of broadcasting, including terrestrial, cable, and satellite, has been placed under the KBC. Government control over media, however, is exercised mainly through administrative guidance to seek the voluntary cooperation of the broadcasters.24

A Chinese television program such as The Great Han Emperor Wu is thus shot with prior approval of its script by SARFT. In addition, the history of the Han Dynasty is well documented, and the script of The Great Han Emperor Wu was based largely on Records of the Grand Historian (史記), by Sima Qian (司馬遷) (ca. 145-90 BCE), who was Emperor Wu’s court historian and featured as a character in the series. A second source was the official History of the Former Han (漢書) by Ban Gu (班固) (32-92 CE).25 (Fig. 8)

Fig. 8: Emperor Wu in middle age (The Great Han Emperor Wu) |

Korean productions such as Jumong, on the other hand, enjoy considerably more flexibility in the script writing and shooting processes. As most television series, including Jumong, begin broadcasting only a couple of weeks after shooting begins, the writers produce “scripts on the fly” during the run of a show. Television productions thus involve a bit of improvisation and even adopt major changes in the original synopsis in response to audience reactions. Because of its enormous popularity, the series run was extended from the originally planned 60 episodes to 81.26 As sources for the story of Jumong and the history of Gojoseon (Ancient Joseon) and Goguryeo were scant and often involve fantastical details,27 the screenwriters had a free license to indulge their imaginations and create a narrative with more realistic details or depart from the original accounts significantly. For example, according to legend Jumong was born from an egg produced by his mother Yuhwa after the sun’s rays impregnated her body.28 In the television series, he was conceived after a union between Yuhwa and resistance leader Haemosu.

The target audience of Chinese and Korean television programs also varies. Chinese television programs are primarily for the consumption of domestic audiences, and its overseas audience is composed mostly of Chinese communities in Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore, North America and elsewhere. Non-Chinese audiences are limited in number except for television adaptations of Chinese literary classics such as The Romance of the Three Kingdoms that do well in East and Southeast Asian markets.29

However, Korean television programs reach both a large domestic market and a huge audience in other Asian nations, as well as Korean and other Asian communities overseas. Since the late 1990s, many East Asian and Southeast Asian nations including China and Japan have been bitten with the Korean Wave (hallyu in Korean; hanliu 韩流 in Chinese, kanryu in Japanese), with Asian consumers eagerly devouring imported Korean popular culture, particularly television serials.30 In 1997 exports of Korean media products amounted only to US$1 million, but grew exponentially thereafter to US$8 million in 1999 and US$29 million in 2002, the first year when Korean media exports exceeded imports in value. In 2009, broadcasting exports (primarily television programs) reached a level of $81 million.32

Nonetheless, the differences should not be overstated. Despite the heavier hand of state regulation in China, Chinese television programming depends more and more on advertising revenues with the dwindling of state subsidies since the 1980s, and thus must respond to consumer tastes and demands while remaining mindful of political boundaries. By the late 1990s, private capital accounts for 80% of total annual investment in television drama production, and 90% of total annual revenues for television stations is derived from advertising, mainly on their drama programs.33 While the export market for Korean television dramas is a significant and expanding source of revenues, the domestic market remains far more important: in 2009, exports account for 24% of total sales in Korea’s broadcasting sales of $337 million.34 Domestic demand and preferences remain the main influence on Korean television production, if to a lesser degree than China’s.

Furthermore, creators of historical dramas in both China and Korea may sacrifice fidelity to historical sources to create more dramatic and entertaining story lines. They may also depart from historical accuracy to pursue specific political and nationalist agendas, both to shape and respond to popular nationalist sentiments. Kim Dong-Seon, the director of the Korean historical drama Dae Jo-yeong, commented in response to queries on historical inaccuracies: “Historical dramas aren’t documentaries. Plot elements may be at odds with the historical record; the aim of shooting the show is to cultivate feelings of pride in young people!”35 Because of the huge audiences it can reach, broadcast media can play a substantial role in fortifying nationalism amongst the people of East Asia, particularly the youth.

The Goguryeo Controversy on Television

Jumong is among those Korean productions that are in tune with mainstream Korean viewers, but run afoul of both Chinese government regulators and Chinese audiences because of their political subtext. Specifically, Jumong directly addresses the Goguryeo controversy from a nationalist Korean perspective by creating a modern national foundation myth on the basis of ancient history that is itself shrouded in mythology. It was banned on Chinese television because its historical perspective of Gogureyo as a successor to Gojoseon and a precursor to later Korean states contradicts the Chinese interpretation of Gogureyo as a Chinese state that had little direct connection to the Goryeo (Koryo) Dynasty (高麗王朝) that unified Korea in 936 CE, aside from the similarity in name.36

The Great Han Emperor Wu does not address the Goguryeo controversy directly, and in its 58 episodes there is no reference to the invasion and conquest of Gojoseon in 108 BCE. Nonetheless, the series is consistent with the conception of the “multi-cultural unity of the Chinese nation” that is at the heart of the Northeast Project’s interpretation of the history of Goguryeo so adamantly rejected by the Koreans. Significantly, the opening title of the very first episode emphasizes: “According to Records of the Grand Historian and History of the Former Han, the Xiongnu (匈奴) and the Han Chinese originally came from one source. They were both descendants of the Great Yü (禹). After the fall of the Xia Dynasty, one branch of the clan of Jie (桀 [the last king of Xia]) fled north and constituted the Xiongnu nationality . . .”37 The Xiongnu, whose conflict with the Han is central to the story of The Great Han Emperor Wu, are thus representative of national minorities whose histories intersected with the history of the Han Chinese and who constitute a part of the Chinese community historically and in the present. According to the television script (but NOT Sima Qian), Emperor Wu is the brother-in-law of the Xiongnu supreme leader (chanyu 單于) by marriage,38 and the war between the Han and the Xiongnu is thus in a sense a family feud.

Jumong, on the other hand, explicitly engages the Goguryeo controversy. The struggle of Jumong and his colleagues to free the descendants of Gojoseon (Ancient Joseon) from the oppression of the Han Dynasty and to recreate the glorious Gojoseon empire is at the heart of the narrative. From the perspective of the creators of Jumong who projected the modern ideas of nationhood and the consciousness of a Korean national identity backward in time, Korea as a nation began with Gojoseon, with Goguryeo founded by Jumong as its successor state. In turn Goguryeo spun off the state of Baekje, and served as the precursor to the unified Korean kingdom under the Goryeo and Joseon dynasties. The peoples of present-day Northeast China and North Korea under Han imperial administration or within its spheres of influence were thus identified as Koreans in Jumong.

Both Jumong and The Great Han Emperor Wu tackle the issues of national identity formation and state building for a nation or nation-in-making in a period of crisis. We will compare their narratives with particular attention to the present-day political environments of China and Korea and the Gogureyo controversy.

Coming-of-Age Narratives as Metaphors for Nation Building

Both series can be seen as coming-of-age narratives, with Liu Che and Jumong growing from an uncertain young adulthood into mature and confident leaders. Their personal growth is emblematic of the growth of the Chinese and the Korean nation respectively. At the beginning of both series, neither Liu Che nor Jumong are likely future leaders of their nation, and both the Chinese and the Korean peoples are confronting serious internal and external threats to their prosperity and even survival.

The story of The Great Han Emperor Wu unfolds in the reign of Liu Che’s father, Emperor Jing, the fifth emperor of the Han Dynasty. Although already in existence for about half a century, the dynasty is still shaky. Internally, it faces a threat from the feudatories (fan 藩), hereditary kingdoms ruled by kinsmen of the imperial Liu family who collectively controlled 39 out of 54 prefectures in the empire, and some of these kings harbor imperial ambitions. Emperor Jing’s attempt to strip away land from some of the feudatories triggers a rebellion by seven of the kings in 154 BCE (episodes 4-7). Although the rebellion is suppressed, the feudatories collectively continue to present a challenge to central power.

Emperor Jing also confronts the problem of succession. He prefers to pass the throne to one of his sons, but they are still very young, and his brother the King of Liang wants to be named heir apparent, with the strong support of their mother Empress Dowager Dou (episodes 1, 8, 11). Should the Han Dynasty uphold the succession principle of father to son, as adopted by the Zhou Dynasty and by Han founder Liu Bang (Emperor Gao 漢高祖劉邦), or should it revert to the succession principle of older brother to younger brother, as practiced by the ancient Xia and Shang dynasties (episode 8)? Among Emperor Jing’s sons, Liu Che, the tenth son and the offspring of an imperial concubine, has initially little hope of becoming the Crown Prince, even though he has impressed his father as a precocious child.39

There is also the question of an ideological struggle: the early Han has adopted a Daoist approach to public policy, and Empress Dowager Dou herself strongly favors Daoism over Confucianism, whereas many officials favored by Emperor Jing and later Emperor Wu are Confucians (episodes 9-10, 15-18).

Externally, the threat stems from the nomadic Xiongnu people who are able to raid the Han frontiers and even challenge the capital of Chang’an with impunity. The Han Dynasty is forced to buy off the powerful Xiongnu, offering their chieftains Han princesses as brides.40

Fig. 9: General Wei Qing (The Great Han Emperor Wu) |

The Xiongnu military superiority over the Han rests on their ability to wage mobile warfare on horseback. In the judgment of Wei Qing (衛青), a general who serves Emperor Wu, the Han cannot defeat the Xiongnu because the latter love their horses and their women, whereas the Han do not. Moreover, the Xiongnu also possess superior steel swords whose sharpness cannot be matched by the Han swords (episode 24). (Fig. 9)

The Koreans in Jumong also confront serious internal and external threats. At the beginning of the series, the mighty Gojoseon has fallen to the Han, having been weakened by internal discord sowed by the Han. Its former territory is splintered between the four commanderies established by the Han Dynasty. Numerous Korean states and micro-states face the choice of accommodating the Han or protecting the refugees from the former Gojoseon at the risk of incurring Han wrath. The Han rules with utter ruthlessness, its Iron Army slaughtering Korean civilians and refugees at will (episode 1).41 The forces of resistance are led by Haemosu, a master archer and leader of the Damul Army, and Geumwa, the crown prince of the state of Buyeo (夫餘). Yuhwa, the princess of the Haebaek tribe, and Haemosu fall in love. After the birth of their son Jumong, Haemosu is apparently killed. Geumwa raises Jumong as his son and marries Yuhwa as his concubine (episodes 1-3).

When the action flashes forward twenty years later, King Geumwa has expanded the territories of Buyeo considerably through military conquest. Jumong is one of the three princes who are potentially heirs to the Buyeo throne. But his prospects are dim even though Geumwa loves and protects him for the sake of Haemosu and Yuhwa. Geumwa has two older sons by his queen Wonhu: Daeso, the oldest, is a superb fighter, while the immature and opportunistic Yeongpo has the affection of his mother. Jumong, on the other hand, is a spoiled and feckless skirt chaser with weak fighting skills (episodes 3-4).

Overcoming their initial weaknesses, both Liu Che and Jumong rise to become leaders of their peoples. Following some palace intrigues leading to the deposition of crown prince Liu Rong (劉榮), Liu Che’s mother Consort Wang (王美人) and her brother Tian Fen (田蚡) are then able to lobby successfully for Liu Che to be named crown prince (episodes 9-14).

Even after ascending to the throne after the death of Emperor Jing, Emperor Wu does not enjoy absolute power. His efforts to reform the court by promoting Confucians are initially thwarted by his grandmother, now the Grand Empress Dowager Dou (太皇太后), who is devoted to Daoism and has control of the military (episode 17). In the middle of a military crisis on the southeastern frontier, the gravely ill Grand Empress Dowager Dou hands Emperor Wu full political authority (episode 27). He is finally able to make Confucianism the supreme ideology for the Han state above all other teachings.

On the foundation of a flourishing economy and the beginnings of a Han military capable of taking on the Xiongnu inherited from his father Emperor Jing, Emperor Wu is now prepared to take the initiative against the Xiongnu. Over fifteen campaigns in the course of two decades, Emperor Wu’s forces finally drive the Xiongnu north of the Gobi. In 51 BCE, 36 years after the death of Emperor Wu, the Xiongnu split into two groups, one going west to invade Europe, the other surrendering to the Han. The blood of the Xiongnu people now intermingles with the blood of the Han (episode 58).

From an inauspicious beginning, Jumong too is able to mature as a leader and fighter, and emerges as a credible contender for the throne of Buyeo. Jumong reunites with his father Haemosu, who turns out not to have been killed. Under Haemosu’s spiritual guidance, Jumong becomes an expert swordsman and archer (episodes 8-12). He assumes his father’s goal of reviving the Gojoseon Empire.42 Jumong leaves Buyeo and rebuilds the Damul Army that Haemosu has led. He saves the Gojoseon refugees from persecution by the Han, defeats the Han Iron Army to gain control of the Han commanderies of Hyeondo and Yodong, establishes the new nation of Goguryeo and becomes its king, after which he continues the fight against the Han (episodes 24 ff.).

Recruiting a Meritocracy for Nation-Building

Besides their personal growth as leaders, what other factors facilitate state building by Emperor Wu and Jumong? The employment and promotion of capable men irrespective of their social status and origins are key to the success of both leaders. Emperor Wu gives important political and military assignments to worthy officials regardless of their family background. General Wei Qing, originally a stable slave whose sister Wei Zhifu (衛之夫) becomes an imperial favorite and ultimately empress, is put in charge of raising horses and creating a military academy. He eventually leads expeditions against the Xiongnu (episode 24). Despite his youth, Wei Qing’s nephew Huo Qubing (霍去病) is appointed to head a campaign against the Xiongnu, and repays Emperor Wu’s trust with a lightning strike that results in the killing and capture of over 32,000 Xiongnu troops. The captive Xiongnu prince Jin Midi (金日磾) is made a personal confidante and official by Emperor Wu (episode 51).

Jumong likewise gathers a group of capable people around him in his ascendancy. He befriends three robbers, Oyi, Mari and Hyeopbo, who become his staunch supporters (episodes 7-8). He allies with Yeontabal, the merchant prince of Gyehru, and his daughter Soseono, who becomes his great love. Their material resources, business skills and managerial talent are instrumental to the prospering of Jumong’s cause. As Jumong builds up his Damul Army, he recruits three more lieutenants from the ranks of resistance fighters against the Han: Mukguh, Jaesa and Moogol (episode 46). Jumong’s leadership qualities win over his would-be assassin Bubunno and pirate leader Buwiyum, who join his Damul Army (episodes 63-64). Particularly important is Mopalmo, director of Buyeo’s iron chamber whose experimentations ultimately lead to discovering the secrets of forging strong steel swords that are more than a match for the weapons of the Han Iron Army. He also invents the smoke bomb and other military devices (episode 58).

Both historical dramas, then, affirm the importance of a meritocracy of skilled officials, warriors, and technical experts in building national greatness. Without the capable advice and services of their loyal followers chosen for their merit regardless of social origins, neither Emperor Wu nor Jumong can succeed in their political quests of nation-building.

Portrayals of External Enemies and Internal Traitors

Fig. 10: The Xiongnu chanyu’s consort (Princess Nangong) and Jin Midi (The Great Han Emperor Wu) |

However, there are fundamental differences in the framing of the nation-building narrative in The Great Han Emperor Wu and Jumong, reflecting the different political goals of cultural constructions of national identity and political priorities for contemporary China and South Korea. For China, national identity and unity are framed as inclusive of groups that are presently characterized as national minorities that together with the Han constitute today’s multiethnic state, and the historical narrative is constructed to support this vision. The Xiongnu in the Han Empire are thus a symbolic representation of national minorities of the present. The Great Han Emperor Wu emphasizes the common roots of the Han and the Xiongnu before even the opening scene unfolds, and throughout the series the Xiongnu are portrayed as real human beings rather than cartoon villains. Though cruel, Chanyu Yizhixie (伊稚斜) is courageous, wily, and a worthy opponent of the Han. The series concludes with the former Xiongnu heir apparent Jin Midi saving Emperor Wu from an assassin and becoming one of a small group of officials to whom the emperor on his deathbed entrusts his infant son who will inherit the throne (episode 58). (Fig. 10) Unity in diversity constitutes the ideal of China’s multiethnic national identity, as expressed in the concept of “a unitary multi-national state” (tongyi de duominzu guojia 统一的多民族国家).43 The territorial integrity of a unified state guarded against the dangers of ethnic separatism is a top priority for both the Chinese state and the Han majority.

National unity also represents a top political goal for the Korean people. In the Korean context, however, national identity centers on a single Korean people unified by culture and history but politically divided since 1945. Unification of north and south, therefore, is the one issue that Korean nationalists are passionate about. Jumong presents unity among the Korean people as the key to national greatness: as Sorceress Bigeumseon reminds Jumong, even the greatest of nations, i.e. Gojoseon, will perish if it cannot remain one. Jumong must unite the scattered peoples of Gojoseon and regain its lost lands (episode 58). The Korean states and tribes are to be incorporated by peaceful means and diplomacy if possible, by war only when necessary. Jumong succeeds in uniting the five tribes of Jolbon with the Damul Army without fighting (episode 60). As a symbol of the alliance, Sorceress Soryung paints a three-legged crow on a yellow banner with the intermingled blood of Jumong and the five tribal chiefs. Jumong comes up with Gogureyo as the name for the new nation, the highest and the brightest in the world (episode 62).44

For Koreans viewing Jumong, Han colonization of Gojoseon aided by Korean collaborators conjures up parallels to and painful memories of the Japanese colonization of Korea from 1910 to 1945 and Korea’s subsequent division. The Chinese and their collaborators in Jumong are portrayed in one-dimensional terms as black villains who stand in the way of national unification, as represented by Jumong’s efforts to reconstitute the glorious Gojoseon. The ruthless and faceless Chinese Iron Army mercilessly slaughters the innocent. The renegade Yangjeong, originally a prince of the state of Gaema and a boyhood friend of Geumwa, is held hostage in the Chinese commandery of Hyeondo but then becomes a military officer (episode 1) and finally the governor of Hyeondo (episode 7). He engages in villainous acts against the Korean people until his demise at the hands of Jumong (episode 71). Yangjeong’s daughter Lady Yangseolan marries Daeso for political reasons (episodes 34-35) and becomes the queen of Buyeo. Cold and power hungry, she ruthlessly abuses Jumong’s wife Yesoya and infant son Yuri. The childless Yangseolan first attempts to poison Yuri (episode 58), and then to take him away and raise him as her son (episode 65). Yangseolan also tries to poison King Geumwa so that Daeso can ascend to the Buyeo throne (episodes 72-73).

Coming off not much better than Yangjeong and Lady Yangseolan are those Koreans who sometimes compromise or collaborate with the Chinese. Geumwa’s second son Yeongpo spends a stint in the court of Chang’an as a hostage of the Chinese, and makes several abortive attempts to use the commercial and political capital he has earned in China to secure the throne of Buyeo. Yeongpo’s older brother Daeso disparages him as being “almost a citizen of Han,” and declares that he, Daeso, as a prince of Buyeo, will never betray his country (episode 57). Yet Daeso himself, as the rival to Jumong for the Buyeo throne and for the affections of Soseono, indulges in treacherous plots against Jumong even way back when Jumong is a hapless incompetent.45 Moreover, on several occasions Daeso allies with the Chinese and their Korean surrogates, forcibly returning Korean refugees to Hyeondo, and fighting alongside his father-in-law Yangjeong against Jumong (episodes 43, 71).

If the Korean collaborators in Jumong all meet their just punishment, its Korean viewers are all too aware of the tortuous path that the resolution of the collaboration issue and the implementation of social justice have taken in South Korea since liberation from Japanese colonial rule.46 Human rights abuses and physical violence were not only committed by the Japanese colonial government and their Korean collaborators, but also by the post-colonial authoritarian governments under Syngman Rhee and then military strongmen from Park Chung-hee to Roh Tae-woo, and by the American military. Due to Cold War considerations, the American military government in the late 1940s decided to employ Koreans who had served in the Japanese colonial administration.47 Consequently a significant percentage of the South Korean government, police and military were former collaborators. During the Korean War, both the South Korean government and the U.S. military committed atrocities against the civilian population.48 From the 1960s, the government came under the domination of former collaborators who had been trained at Japanese military academies and colleges in Manchukuo during the 1930s, including most notably Gen. Park Chung-hee.49 Political repression and state violence against civilians continued, climaxing in the Gwangju (Kwangju) Massacre of 1980.50

With former collaborators accounting for a high percentage of its members and seeking to legitimize itself as the product of the independence movement, the South Korean government sponsored the creation of a “myth of national resistance that serves as the foundation myth to the Republic of Korea” and relegates collaboration to the realm of an aberration committed by a tiny minority of traitors.51 There was consequently a “cloak of silence” on the collaboration issue until the 1990s.52 As the democracy movement gained momentum, the resolution of the collaboration issue is viewed as a precondition for “the eradication of vestiges of Japanese imperialism and the restoration of national righteousness,” and a necessary step towards national unification. Concomitantly, proponents of necessity to pursue truth finding about state violence against South Korean civilians, often committed by former collaborators, is necessary not only for the restoration of honor to the victims and their families but also to advance national reconciliation.53

Accordingly, in December of 2005 President Roh Mu-hyun set up the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, with a charge “to foster national legitimacy and reconcile the past for the sake of national unity by honoring those who participated in anti-Japanese movements and by exposing the truth through investigation of incidents of human rights abuses, violence, and massacres that occurred throughout the course of Japanese rule until the present time, especially under the nation’s authoritarian regimes.”54 In addition, President Roh established the Investigative Commission on Pro-Japanese Collaborators’ Property in 2006.55 As of 2010, “more than 75% of cases concerning repression of Korean civilians by the South Korean dictatorship and military have been completed,”56 and 168 collaborators have been identified, the assets of whose descendants were seized by the Korean government, with the proceeds “distributed to the families of resistance fighters and to support projects commemorating the independence movement.”57 However, Kim Dong-choon, retired Standing Commissioner of the Truth and Reconciliation Committee, is pessimistic about the full achievement of social justice, as current President Lee Myung-bak and the new chair and standing commissioners he appointed are “hostile to the spirit of the Commission,” and many pending cases remain unresolved.58

International Relations in the Nation-Building Narratives

Related to the question of national identity is the question of regional and global political and cultural relations. China seeks to project to the world an image of a peacefully rising nation that is eager to engage with and learn from foreign nations. While The Great Han Emperor Wu is targeted at domestic and overseas Chinese audiences, its narrative is consistent with this peaceful self-image for the world.

One significant problem that confronts both Emperor Wu and Jumong is how to neutralize the military advantages of their external enemies. Emperor Wu relies on building up a supply of horses and cavalry units that are capable of fighting the Xiongnu on their own terms. Diplomacy, however, is also an important part of his strategy. While not interested in reaching a diplomatic settlement with the Xiongnu, he dispatches Zhang Qian (張騫) to the Western regions (西域) to collect intelligence about the Xiongnu, to approach potential allies against the Xiongnu, and to acquire the foreign iron technology that is the source of the Xiongnu’s superior weapons and that Han artisans are unable to replicate (episodes 24, 26). Towards the end of his life Emperor Wu enters into a political dispute over how to solve the Xiongnu problem with his heir apparent, the Crown Prince Liu Ju (劉據). Emperor Wu favors continuing the hard line against the Xiongnu, but the prince argues for a peaceful diplomatic solution so that the country which has been bankrupted by protracted foreign campaigns can recover. Liu Ju is eventually falsely accused of fomenting a rebellion and commits suicide (episodes 56-7). Shortly before his death Emperor Wu visits a veterans’ village, and cries at the great sufferings of its inhabitants. He comes to recognize the futility of warfare: the empire has greatly expanded its territories, yet people are starving, and the total population has actually declined by almost half. Issuing an edict condemning himself, he declares that no more wars should be waged. On his death bed, Emperor Wu entrusts Jin Midi with making peace with the Xiongnu and resuming a peace alliance through marriage (和親) (episode 58).

For Jumong, there is never any question of reaching a diplomatic settlement with or in any way accommodating the Han. Jumong and his followers, along with Soseono and her supporters, are committed to driving out the Han and building up Goguryeo, unlike Daeso, Yeongpo and others who make compromises and even collaborate with the Chinese. The narrative of Jumong supports the ideal of national unification through peaceful incorporation of Korean factions and uncompromising resistance against external occupiers.

Korean Technological and Institutional Superiority in Jumong’s Nation-building Narrative

Fig. 11: Map of Gojoseon (Ancient Joseon) (Jumong) |

Furthermore, the tradition of Gojoseon, portrayed in Jumong as equal or superior to Chinese civilization in antiquity and accomplishments, serves as a source of ideas and an inspiration. Jumong acquires from a merchant an ancient map of Gojoseon (episode 58), which reveals that its vast territories covered not just North Korea and Northeast China, but practically half of China Proper (Fig. 11)! If the Chinese claim the Korean peninsula north of the Han River as ancient Chinese territory through its Northeast Project, then the Koreans will repay in kind by claiming most of North China as the domain of Gojoseon.59

Fig. 12: Sacred Treasure of Gojoseon 1: The Damul Bow (Jumong) |

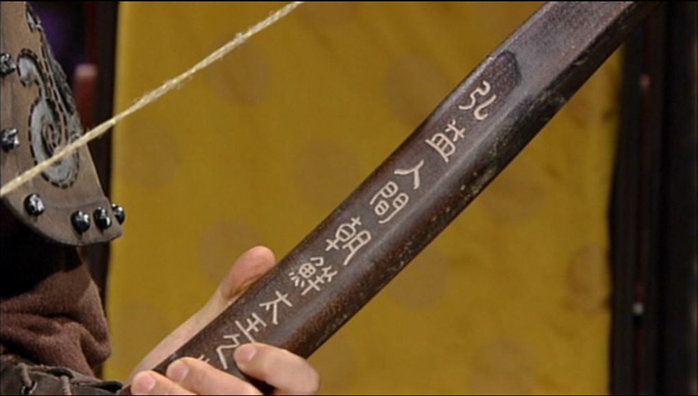

Sorceress Bigeumseon informs Jumong that he has to acquire a set of three sacred treasures of Gojoseon to fulfill his mission of establishing Goguryeo. She first reveals to him the Damul Bow, and tells him that it is not the national treasure of Buyeo, as commonly believed, but that of Gojoseon (Fig. 12). The bow symbolizes Gojoseon’s role as the ruler of the world for the good of humanity, as indicated by its inscription: “The property of the great king of Joseon benefiting humankind (弘益人間朝鮮太王之物).” The rulers of Buyeo have been selected by the gods to reconstitute Gojoseon, but they failed by abandoning the Korean refugees to the oppression of the Han. Jumong is now the chosen one, but he will have to struggle for his quest and earn the other two treasures (episode 58).

Fig. 13: Sacred Treasure of Gojoseon 1: The Damul Bow (Jumong)

|

Following Jumong’s unification of the five microstates of Jolbon and proving his merit, Bigeumseon reveals to him the second sacred treasure: the iron armor of the rulers of Gojoseon, along with a manual of secrets of its Iron Army (Figs. 13 and 14). Mopalmo, the weapons master for Jumong, has been unsuccessful in producing a light and impenetrable iron armor suited to the mobile fighting style of the Damul Army. After Soseono’s adviser Sasong succeeds in deciphering the coded manual, Molpalmo is able to mass produce light armor for Jumong’s forces (episode 68), in time for a showdown with the forces of Hyeondo (episodes 70-71).

Finally, an old man shows Jumong the third sacred treasure of Gojoseon which has been hidden in an underground library: an ancient bronze mirror with inscriptions in an ancient script as old as or older than Chinese writing (Fig. 15) (episode 72).

What is particularly striking in the nation-building narrative of Jumong is its insistence on Korean intellectual and technological superiority and self-reliance, a reflection perhaps of contemporary Koreans’ pride in their cutting-edge leadership in consumer electronics and certain other high-tech sectors. Moreover, Jumong‘s highlighting of advanced material culture in Korean antiquity serves to downplay the significant impact of Chinese culture on Korean civilization in the past. Not only has Mopalmo not borrowed Chinese military technology, he has surpassed the Chinese in weapons development, by relying on the persistence and the ingenuity of himself and his apprentices and on the military manual of Gojoseon.

Fig. 15: Sacred Treasure of Gojoseon 3: The Bronze Mirror (Jumong) |

When Jumong establishes Goguryeo, he entrusts Mari, Jaesa and Sasong to set up its legal and institutional framework. Jaesa suggests The Rites of Zhou (周禮), the source of Han institutions, as a possible model. Sasong, however, is against adopting the Han system. When Jaesa states that one should learn from one’s enemies, i.e. the Han, Sasong counters that the Han system has too many extraneous elements. Sasong further states that Gojoseon has few titles and only eight laws, and yet has been able to maintain peace and harmony: the ruler’s wisdom and honesty are more important than any law. The constitution of Goguryeo is thus to be based not on the Han system, but on the precedents of Gojoseon (episode 73). As in the case of technology, asserting Korean autonomy and distinctiveness from the Chinese constitutional and legal model is an important agenda for Korean nationalists.

The Portrayal of Women and Gender Issues

The treatment of gender issues in the narratives of The Great Han Emperor Wu and Jumong is also revealing. Sticking close to the historical sources and reflecting the traditional Confucian historiographical bias against women meddling in politics, The Great Han Emperor Wu presents a number of women who engage in palace intrigues that destabilize the state. Several women characters fit one or both of the two tropes of femmes fatales who caused dynastic ruin in Chinese historiography: the corruptive seductress who charmed political men into indulging in sensualities and neglecting their public duties; the unprincipled schemer who plotted to grab political power for herself or for her family.60

Both Consort Li (栗姬) and Consort Wang (王美人) scheme to have their sons appointed as crown prince of Emperor Jing. Liu Ling (劉陵), the daughter of Liu An (劉安), the King of Huainan (淮南王), is a master spy who resorts to the honey trap to help her father gain the throne. She has a brief liaison with Emperor Wu (episode 19) and then a long affair with his uncle Tian Fen (田蚡) (episodes 20, 28). She serves as her father’s diplomat to Grand Empress Dowager Dou, ingratiating the latter with the Daoist compendium that the King of Huainan has sponsored. She gathers intelligence for her father (episode 31), and conspires with the Xiongnu (episode 44).

The only significant exception to this coterie of designing women is Empress Dowager Dou, who despite her conservative politics and opposition to reform, does not move to depose Emperor Wu and seize power for her own family, even after his abortive attempt to bypass her authority and to bring Confucians into government through palace examinations to recruit the wise and the virtuous (episodes 17-18). More importantly, it can be argued that by restraining the emperor, she is in fact preventing him from prematurely attacking the Xiongnu before the country is ready. Not only does she not interfere with his military buildup, she also gracefully yields power to him when the time comes (episodes 28, 30).

There are some scheming villainesses in the Jumong narrative. Aside from Yangseolan, Queen Wonhu, though a loving mother to her sons Daeso and Yeongpo, engages in palace intrigues to promote them and her own clan. When King Geumwa is in a coma after being wounded in battle, Queen Wonhu prods Daeso to execute the officials loyal to King Geumwa to pave the way for Daeso to seize and consolidate power: “Bloodshed is a must to gain absolute power,” she tells Daeso (episode 34).

But generally women play a much more positive role in Jumong than in The Great Han Emperor Wu. Yuhwa is a woman of moral courage. When Han soldiers slaughter a group of captured Gojoseon refugees in front of an audience of Korean envoys at the court of the governor of Hyeondo Commandery, Yuhwa protests this massacre while other envoys, including Geumwa, keep silent fearing retaliation. She shelters the wounded Haemosu at great risk to her village (episodes 1-2). The sorceresses are important political actors, reflecting a time when shamanism was central to political and spiritual life. Although not all-powerful magicians who can alter destiny, the sorceresses nonetheless impact political events. Both Yeomieul and Bigeumseon serve as spiritual advisers to Jumong and facilitate his fulfillment of his destined role as the builder of a new nation that revives the ancient glories of Gojoseon.

Even more important is Soseono, who is both an enterprising merchant and a strong leader. She becomes a key ally of Jumong in his political quest, and marries him after the founding of Goguryeo. When it transpires that Jumong’s consort Yesoya and son Yuri are not dead after all, she gracefully leaves with her sons Biryu and Onjo by her first marriage, so that there will be no succession struggles between them and Yuri, and also to expand beyond the territory of Gojoseon by moving south with her people. The Jumong narrative credits Soseono with founding Baekje, one of the Three Kingdoms. While Jumong stays to carry on the fight against the Han and against Daeso, Soseono is engaged in a peaceful expansion into mostly virgin land. Jumong assigns his arms master Mopalmo to go with Soseono so that he can make farming tools for her new nation (episode 81).

This leading role played by strong women in Jumong (and in other Korean costume dramas such as Jewel in the Palace and Damo) contrasts with the mainstream national historiography on Goguryeo, in which national heroes are constructed as masculine and military victories are the product of Korea’s virile “national masculinity,” as Yonson Ahn notes.61 Perhaps the positive and prominent roles of women in television dramas reflect a commercial concession to women viewers who constitute the largest number of consumers of television programs, or an ideological support for gender equality in contemporary Korean society, or both.

Epilogue

Given the strongly nationalistic bent of Jumong and its negative portrayal of the Chinese, it is not surprising that it was banned in China, despite its high production value and entertaining narrative, and despite the general popularity of Korean television dramas in China.62 The most recent Korean historical drama to arouse the ire of SARFT and Chinese netizens is The Four Guardian Gods of the King (太王四神记), which marks the return to television of Bae Yong-joon, the star of Winter Sonata (2002) that was a huge hit in Asia, particularly Japan. Along with several other banned Korean history serials, The Four Guardian Gods of the King (2007), the Chinese authorities accused it of grossly distorting history. In Yeon Gaesomun (渊盖苏文), Tang Taizong, one of the greatest emperors in Chinese history, “is depicted as an ugly, foolish invader who is blinded in his left eye by the Goguryeo Generalissimo Yeon Gaesomun, while the Tang army must beg for mercy from Goguryeo before they are allowed to return to the Tang.”63

The author would like to express his deep gratitude to Yonson Ahn, Kyoko Selden, and Mark Selden for their many substantive and stylistic suggestions and comments on an earlier draft of this paper.

Robert Eng is Professor of History and Director of the Asian Studies Program and the ASDP Regional Center, University of Redlands. He is the author of Economic Imperialism in China: Silk Production and Exports, 1861-1932. He can be reached at [email protected].

Recommended Citation: Robert Y. Eng, “China-Korea Culture Wars and National Myths: TV Dramas as Battleground,” The Asia-Pacific Journal Vol 9, Issue 13 No 4, March 28, 2011.

Notes

1 The best and most objective evaluations of the Chinese and Korean positions in this dispute over history include: Yonson Ahn, “Competing Nationalisms: the Mobilisation of History and Archaeology in the Korea-China Wars over Koguryo/Gaogouli,” Japan Focus (9 February 2006); and Mark Byington, “The War of Words Between South Korea and China Over An Ancient Kingdom: Why Both Sides Are Misguided,” History News Network (6 September 2004) .

2 Yonson Ahn (2006).

3 Research by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences’ Northeast Project (东北工程), or the Northeast Borderland History and the Chain of Events Research Project (东北边疆历史与现状系列研究工程), was conducted from 2002 to 2006. Details of the project are provided in Yoon Kwy-Tak, “China’s Northeast Project and Korean History,” Korea Journal (Spring 2005): 147-155. The Web site of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences’ Research Center for Chinese Borderland History and Geography (中国社会科学院中国边疆史地研究中心), which has information on the Northeast Project and other borderland projects, is no longer online, but may be retrieved through the Internet Archive Wayback Machine at . A representative work of the project on Goguryeo is Huang Bin (黄斌) and Liu Housheng (刘厚生), Gaogouli shihua 高句丽史话 (Huhhot: Yuanfang chubanshe, 2005).

4 Park Kyeong-chul, “History of Koguryo and China’s Northeast Asian Project,” International Journal of Korean History, 7 (February 2005): 19. Park’s article provides a South Korean perspective on Goguryeo’s centrality in Korean history: “Koguryo can be seen as the core entity that spatially links the state founded by the Yemaek tribes in Manchuria i.e. Old Choson-Puyo-Parhae, with modern Korea. Moreover Koguryo also serves as the temporal link through which the continuity of the Korean nation, from Choson-Puyo – Parhae-Koryo to modern Korea, can be perceived.” Park also provides a summary of assertions by Chinese scholars in the Northeast Asia Project and rebuttals by South Korean scholars (Park, 18-24).

Among Western scholars of Korean Studies, Mark Byington and Gari Ledyard argued against the Chinese position on the ground that it is “a direct projection of the current conception of the multiethnic PRC state backward in time … to make “tributaries” and client states appear as though they formed part of a greater Chinese nation and were, by the way, quite conscious of their role as such.” On the other hand, other scholars, including John Jamieson and Andrei Lankov, maintained that Korean claims of Goguryeo as a Korean state are no more credible: Goguryeo was less culturally related to the Han (韓) peoples of Silla and Baekje in Southern Korea than being a component of the “coherent pastoral/agricultural northern continuum that inhabited what is today China’s Three Northeastern Provinces … large parts of Mongolia, Southern Siberia and Russia’s Maritime Region.” Finally, John B. Duncan, Edward J. Schultz and others strongly supported Korean claims: while traditional Chinese historical works treated Goguryeo as external to China, Goguryeo has been “an important part of the Korean collective historical memory for at least the past 1,000 years,” and therefore “to argue that Koguryo was not Korean is equivalent to saying Korea is not Korea …” See the discussion of this issue on the Korean Studies Discussion List in January of 2004; John B. Duncan, “Historical Memories of Koguryo in Koryo and Choson Korea,” Journal of Inner and East Asian Studies 1 (2004): 117-136); Edward J. Schultz, “How English-Language Scholarship Views Koguryo,” Journal of Inner and East Asian Studies 3, no. 1 (2006): 79-94.

5 Khang Hyun-sung, “China’s Historical Claim to the Warrior Kingdom of Koguryo Unites Koreans,” South China Morning Post (2 March 2004), reposted in History News Network. However, it should be pointed out that although both North and South Koreans opposed Chinese historical appropriation of Goguryeo as a Chinese state, North Korea emphasized the centrality of Goguryeo in Korean history to a greater degree than South Korea, because of the location of North Korea in the former territories of Goguryeo. In the official historiography of North Korea, Goguryeo was a successor state to Gojoseon founded by the mythical Dangun, the excavation of whose tomb was announced in October 1993. Moreover, Goguryeo was founded not in the commonly accepted date of 37 BCE after Silla’s foundation in 57 BCE, but much earlier in 277 BCE. Finally, it was Goguryeo, not Silla, that took the initiative in the unification of the Three Kingdoms, and it was Goguryeo more than either Silla or Baekje that was central to the formation of Korean ethnic identity. “History Dispute Between North Korea and China,” Vantage Point 27, no. 3 (March 2004): 14-15; Yangjin Pak, “Contested Ethnicities and Ancient Homelands in Northeast Chinese Archaeology: the Case of Koguryo and Puyo Archaeology,” Antiquity 73 (September 1999): 615-616.

6 Andrei Lankov, “The Legacy of Long-Gone States: China, Korea and the Koguryo Wars,” Japan Focus (28 September 2006) . An unofficial translation of the five-point ‘verbal agreement’ is available in Terence Roehrig, “History as a Strategic Weapon: The Korean and Chinese Struggle over Koguryo,” in Korean Studies In the World: Democracy, Peace, Prosperity, and Culture, ed. Seung Ham Yang, Yeon Sik Choi, and Jong Kun Choi (Seoul: Jimoondang, 2008), 106-107. Chinese officials, however, did not acknowledge that Goguryeo was part of Korea.

7 When North Korea applied to UNESCO to have the Goguryeo sites within its boundary designated as World Heritage sites in 2000, the Chinese followed suit with their application for World Heritage status for Goguryeo ruins within China’s Northeast in 2003. A related flashpoint is the dispute over Mount Baekdu (Korean) /Mount Changbai (Chinese) on the China-North Korea border, touching on issues of national identity, historical greatness, territorial claims and economic interests for China and the two Koreas. This mountain range is the putative birthplace of both Dangun, the legendary founder of Gojoseon (Ancient Joseon), and Bukuri Yongson, ancestor of Nurhaci of the Aisin Gioro Imperial clan that ruled China from 1644 to 1911. For a detailed analysis of this dispute, see Yonson Ahn, “China and the Two Koreas Clash over Mount Paekdu/Changbai: Memory Wars Threaten Regional Accommodation,” Japan Focus (27 July 2007). See also Roehrig (2008), 95-101.

8 In polls taken by the Pew Global Attitudes Project, the percentage of South Korean respondents who held a favorable view of China dropped from 66% in 2002 to 52% in 2007 to 38% in 2010, while the corresponding figures for respondents with an unfavorable view were 31%, 42% and 56%.

9 South Korea successfully applied in 2005 to have UNESCO list its Gangneung Danoje Festival as an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. Because the Gangneung Danoje Festival and China’s Duanwu Festival or Dragon Boat Festival have the same name in Chinese characters (端午), and both take place on the 5th day of the 5th month of the lunar calendar, the Chinese were incensed at what they saw was an infringement of China’s cultural heritage. They were further aggravated by reports that Korea has also “applied to have its ritualized Confucius memorial ceremony listed as another unique cultural heritage and is reportedly ready with an application for the listing of “Chinese traditional medicine” as “Korean traditional medicine.”” In 2009, China successfully applied for inclusion of its Dragon Boat Festival on UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage List. Antoaneta Bezlova, “The Fun’s Going out of Chinese Festivals,” Asia Times (27 February 2008); Zhu Shanshan, “Dragon Boat Festival named a UNESCO intangible cultural heritage,” Global Times (2 October 2009) .

10 Charles E. Morrison, “Challenges for Internationalism for International Cooperation in the Asia-Pacific Region,” Keynote address, 14th National Conference of the Asian Studies Development Program (7 March 2008, Chicago). Morrison identifies ethno-nationalism as the number one challenge for the Asia-Pacific Region today.

11 In Magnus Fiskesjö’s view, this model is a contemporary reformulation of the imperial Chinese model, which posits Chinese civilization as the transformative force for the enlightenment of the primitive barbarians of the periphery. The Communist government carried out a large-scale ethnic classification project in the early 1950s to “classify, order, even invent where necessary, once and for all, all the non-Han minority ethnicities.” A system of “constrained autonomy for non-Han peoples” was institutionalized as a hierarchy of autonomous administrative units from the Autonomous Region on down, with legal provisions for the protection of the rights of minority nationalities, and preferential treatment for minorities in a number of areas. Magnus Fiskesjö, “Rescuing the Empire: Chinese Nation-Building in the Twentieth Century,” European Journal of East Asian Studies, V, no. 1 (2006): 15-44. Fiskesjö, however, may have underestimated the far more intrusive nature of PRC policies.

Not only was the classification of ethnic minorities itself problematic, but the lumping together of many peoples in China proper with distinct Chinese dialects or topolets, cultures, and histories into an undifferentiated Han majority may also be questioned. Moreover, as Bin Yang points out, the term minzu (民族) can refer to both the entire Chinese nation (Zhonghuaminzu 中华民族) and each of the 56 officially recognized minzu that constitute the Chinese nation. The translation of minzu as either nationality or ethnic group is thus problematic, given that minzu is “a state invention and construction” applied only to ethnic groups recognized by the Chinese government, while “ethnicity is shifting and flexible.” Bin Yang, “Central State, Local Governments, Ethnic Groups and the Minzu Identification in Yunnan (1950s-1980s),” Modern Asian Studies 43, no. 3 (May 2009): 744.

12 Yoon Hwy-Tak (2005), 145-146.

13 Both Peter Hays Gries and Jungmin Seo point out modern Korean nationalism requires the construction of a historical narrative emphasizing the virile masculinity of Korea’s past as represented by Goguryeo’s resistance to China, given the subordination of the Joseon Dynasty to Ming and Qing China and the colonization of Korea by Japan. Borrowing the Japanese neologism minzoku (民族) or nationality, the writer Shin Chae-ho (1880-1936) discovered the heroic roots of the Korean minjok in the militaristic and expansionist exploits of Goguryeo. Gries (2005), 9; Jungmin Seo, “The Politics of Historiography in China: Contextualizing the Koguryo Controversy,” Asian Perspectives 32, no. 3 (2008): 43. While the Japanese concept of minzoku, the Chinese concept of minzu, and the Korean concept of minjok may have common etymological origins and are employed for nation-building purposes, their usage differs. Minzu refers to both the entire Chinese nation and each of the 56 constituent nationalities, whereas minzoku and minjok refer exclusively to the Japanese people and the Korean people respectively. Cf. footnote 11 above.

14 For the role played by archaeology in this debate over the ownership of Goguryeo’s heritage, see: Yonson Ahn, “The Contested Heritage of Koguryo/Gaogouli and China-Korea Conflict,” Japan Focus (11 January 2008); Kang Hyun Sook, “New Perspectives of Koguryo Archaeological Data,” in Early Korea: Reconsidering Early Korean History Through Archaeology, ed. Mark E. Byington (Cambridge, Mass.: Early Korea Project, Korea Institute, Harvard University, 2008), 13-63; also “History Dispute Between North Korea and China” and Yangjin Pak (1999) cited in note 5 above.

15 “Han Wu Da Di juzu jieda 汉武大帝剧组解答,” Quanzhou wanbao 泉州晚报 (20 January 2005).

16 The part of Liu Che who eventually became Emperor Wu was assumed by four actors, including top television star Chen Baoguo (陈宝国) as the adult emperor. A stellar cast included noted Taiwan actress Kuei Ya-Lei (歸亞蕾) in the role of Empress Dowager Dou (竇太后), the grandmother of Emperor Wu. “Facts and Flaws Make Up Epic TV Tales” People’s Daily Online (2 February 2002).

17 Ying Zhu, “Zhongzheng Dynasty and Chinese Primetime Television Drama,” Cinema Journal 44, No. 4, (Summer 2005): 3.

18 Song Il-Kook starred in the title role, with Han Hye-Jin co-starring as his great love and political ally Soseono. Jumong was directed by Lee Ju-Hwan and Kim Geun-Hong. Jumong Reference Guide, Part II, included with Jumong DVD set (YesAsia Entertainment, 2007).

19 Its official Web site is located at www.sarft.gov.cn.

20 See Joel Martinsen, “Harmonious Society vs. Popular Television,” Danwei (27 August 2006); and Joel Martinsen, “Putting a Stop to Historical Re-enactment,” Danwei (2 March 2006). In 2005, SARFT issued “The Measures for Strengthening the Administration of Import of Cultural Products,” which introduced a declaration system for such imports, and required prior examination and approval of overseas TV serials, animations and TV programs (Hong Kong Trade Development Council (HKTDC), “Cultural Products Import Administration Strengthened” (1 September 2005)). The latest set of regulations regarding the contents of television dramas, effective as of May 14, 2010, may be found on SARFT’s site.

21 Preeti Bhattacharji, Carin Zissis, and Corinne Baldwin, “Media Censorship in China,” Council on Foreign Relations (27 May 2010).

22 Ying Zhu, Michael Keane, and Ruoyan Bai, “Introduction,” in TV Drama in China, ed. Zhu, Keane, and Bai (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2008), 10.

23 Stanley Rosen, foreward to Ying Zhu, Television in Post-Reform China (London and New York: Routledge, 2008), xvii.

24 Philip Kitley, Television, Regulation, and Civil Society in Asia (London and New York: RoutledgeCurzon, 2003): 47-48. The KBC’s introduction to its functions can be found on its Web site.

25 The show was criticized by some for alleged anachronisms, factual errors, inappropriate costumes and sets, and mispronunciations, but on the whole was praised for historical veracity. “Facts and Flaws Make Up Epic TV Tales.”

26 Jumong Reference Guide, Part II, 7, 20.

27 The translation of an epic poem about the establishment of Goguryeo by Jumong, written by a Goryeo (Koryo) scholar in the early 13th century on the basis of folk beliefs and legends, is found in Sun-hee Song, “The Koguryo Foundation Myth: An Integrated Analysis,” Asian Folklore Studies 33, no. 2 (1974): 41-45. Another version of this myth, based on this poem and also Goryeo period historical works on the Three Kingdoms including Samguk Sagi and Samguk Yusa, is “King Tongmyong, the Founder of Koguryo,” in Hwang Pae-Gang et al., Korean Myths and Folk Legends (Fremont, Calif.: Jain Publishing, 2006), 13-30. See also Ken Gardiner, “Beyond the Archer and His Son: Koguryo and Han China,” Papers on Far Eastern History 20, no. 20 (September 1979): 57-82.

28 Ki-baek Lee, A New History of Korea, translated by Edward W. Wagner with Edward J. Schultz (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard-Yenching Institute, 1984), 7.

29 Ying Zhu, Television in Post-Reform China (London and New York: Routledge, 2008), 7.

30 Although Chinese broadcasters are limited to a screening a maximum of 20% foreign programming, China has aired an increasing quantity and higher quality of imported television programs since the 1980s. The broadcasting of a popular Korean drama, Where on Earth is Love?, on CCTV in 1994 opened the door for a growing number of Korean serials imported. Korea subsequently became a leading exporter of cultural products to China, along with the United States and Japan. Park Sora, “China’s Consumption of Korean Television Dramas: An Empirical Test of the “Cultural Discount” Concept,” Korea Journal (Winter 2004): 269-270.

31 Park (2004), 268.

32 Korea Creative Content Agency, “Main Statistics of Korea Content Market”

33 Ying Zhu, Michael Keane, and Ruoyan Bai, “Introduction,” in TV Drama in China, ed. Zhu, Keane, and Bai (Hong Kong: Kong Kong University Press, 2008), 10.

34 “Main Statistics of Korea Content Market.”

35 Joel Martinsen, “Korean History Doesn’t Fly on Chinese TV Screens,” Danwei (17 September 2007).

36 A list of South Korean costume dramas that have been accused by the Chinese of altering history can be found at “Bada Hanju siyi cuangai Zhongguo lishi! 八大韩剧肆意篡改中国历史!” Zailushang 在路上(9 March 2009) . Most of these dramas were banned, but even those that had been approved by SARFT were criticized by Chinese netizens or subjected to state-mandated cuts. Empress Min (明成皇后) was broadcast in China with cuts for content that allegedly distorted Chinese history. There was even controversy surrounding Dae Jang Geum (大长今), also known as Jewel in the Palace, a fictionalized series about a Joseon Dynasty woman who became Korea’s first female royal physician that was a huge hit with Chinese audiences. Some Chinese netizens accused this drama of appropriating Chinese acupuncture, herbal medicine and culinary methods as Korean heritage, thus guilty of cultural theft. See Lisa Leung, “Mediating Nationalism and Modernity: The Transnationalization of Korean Dramas on Chinese (Satellite) TV,” chapter 3 in East Asian Pop Culture: Analysing the Korean Wave, ed. Chua Beng Huat and Koichi Iwabuchi (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2008), 65.

37 It is indeed stated in juan 110 of Records of the Grand Historian that the Xiongnu’s ancestor, Chun Wei (淳維), was a descendant of the rulers of the Xia. Sima Qian, Shi Ji (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1959), juan 110, 2879.

38 According to the script of The Great Han Emperor Wu, Emperor Jing marries off his daughter and the future Emperor Wu’s older sister Princess Nangong (南宫公主) to the Xiongnu chanyu. However, Sima Qian’s Records of the Grand Historian states that Princess Nangong was first married to Marquis Zhang Zuo (張坐) and then to Marquis Er Shen (耏申). Some Song Dynasty sources do state that Princess Nangong was married to the chanyu, but this is contradicted by Sima Qian’s many mentions of the princess’ presence at the Han court. Moreover, under the Han policy of marriage alliance with the Xiongnu to buy peace (和親), the highest ranking woman aristocrats sent to marry the chunyu were daughters of kings and marquises, never imperial princesses. See the “Nangggong gongzhu 南宫公主” entry in Baidu Baike (百度百科).

39 Liu Che overturns a verdict on a complicated murder case involving a stepson who discovers that his stepmother has murdered his father years earlier and kills her. He argues that the stepson should not be convicted of matricide and sentenced to death by slicing since the stepmother is not his birth mother and demonstrates that she has no feelings of family affection by her act of murder. The stepson should therefore be convicted of ordinary murder. However, given the extenuating circumstances of his avenging his father’s wrongful death, his death sentence should be commuted to hard labor (episode 12).

40 Emperor Jing makes palace maid Qiuxiang (秋香) Princess Longqing (隆慶公主) and sends her to marry the Xiongnu chieftain (episode 3). However, the Xiongnu detect the deception and attack the frontier. Emperor Jing is then forced to send a real princess, his daughter Princess Nangong (南宮公主) (episode 8). As pointed out in footnote 38 above, this version contradicts Sima Qian’s Records of the Grand Historian.

41 According to historian Ki-baik Lee, however, “China’s colonial policy does not seem to have been marked by severe political repression” (Lee, 20).

42 Jumong conceives Gojoseon to be an empire ruling over vast territories in North Korea, and Northeast and North China. According to Ki-Baik Lee, however, Gojoseon was originally a walled-town state occupying the Daedong river basin at Pyongyang, which sometime before the 4th century BCE formed a large confederation with other walled-town states in the region between the Daedong and Liao rivers. In this interpretation, the rulers of Gojoseon were thus kings of a confederated kingdom rather than an imperial state (Lee, 14).

43 Bin Yang (2009), 743.

44 According to Kang Hyun Sook of Dongguk University, “Gogureyo” is a compound composed of the Chinese character 高, meaning large or high, and the phonetic compound 句麗, meaning village or walled town. “Together the meaning becomes large village or large fortress.” Kang (2008), 13.

45 When the three brothers are sent to a sacred mountain to search for the Damul Bow, Daeso and Yeongpo trick Jumong into a swamp, leaving him to die there (episode 4).

46 See the detailed analysis by Koen de Ceuster in his “The Nation Exorcised: The Historiography of Collaboration in South Korea,” Korean Studies, 25, no. 2 (2001): 207-242. The issue of wartime collaboration applies to all countries under occupation during World War II. See Timothy Brook, Prasenjit Duara, Suk-Jung Han, Heonik Kwon, and Margherita Zanasi, “Collaboration in War and Memory in East Asia: A Symposium,” Japan Focus I (5 July 2008).

47 Ceuster, 210-1.

48 The South Korean government carried out numerous summary executions of civilians and political prisoners suspected of posing a threat to the Rhee regime. The ROK police and right wing youth groups arrested and executed people suspected of collaborating with North Korea. Counterinsurgency against Communist guerrilla claimed numerous innocent lives. Kim Dong-choon, “The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Korea: Uncovering the Hidden Korean War,” The Asia-Pacific Journal (1 March 2010). The single biggest massacre of South Korean civilians committed by the U.S. military was the No Gun Ri Incident of 1950, in which hundreds were killed. Suhi Choi, “Silencing Survivors’ Narratives: Why Are We Again Forgetting the No Gun Ri Story?” Rhetoric & Public Affairs, 11, No. 3 (Fall 2008): 367-388.

49 Suk-Jung Han, “On the Question of Collaboration in South Korea,” Japan Focus (4 July 2008) . It was this group of generals and technocrats who had remade themselves into anti-Japanese fighters and promoted a strategy of state-led industrialization on the Manchukuo model.

50 In-sup Han, “Kwangju and Beyond: Coping with Past State Atrocities in South Korea,” Human Rights Quarterly, 27, no. 3 (August 2005): 998-1045.

51 Ceuster, 216-7. Note that this master narrative of heroic resistance as the roots of ROK is paralleled by both the historical narrative of a heroic and masculine Korea pioneered by Shin Chae-ho, and by the narrative of Jumong.

52 According to Koen de Ceuster, a counter-narrative to this ROK foundation myth surfaced first in the maverick scholarship of Im Chongguk as early as 1966, although it was only in the 1980s that his publications constituted “the first integrated efforts at coming to terms with this issue of collaboration.” However, it was not until the 1990s when a critical mass of writings on collaboration by junior scholars and journalists was published, by which time the issue had become socially relevant. Ceuster, 219-222.

53 Ceuster, 219.

54 Ahn Byung-Ook, ed., Truth and Reconciliation: Activities of the Past Three Years (Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Republic of Korea, 2009), 14.

55 Julian Ryall, “South Korea Targets Japanese Collaborators’ Descendants,” The Telegraph, 14 July 2010 .

56 Kim Dong-choon and Mark Selden, “South Korea’s Embattled Truth and Reconciliation Commission,” The Asia-Pacific Journal (1 March 2010) .

57 Ryall, op.cit.

58 Kim and Selden, op.cit.

59 In a parallel fashion to Jumong’s attribution of a vast territory to Gojoseon, North Korean historians assert that Goguryeo’s boundaries between the 4th and 5th centuries extended to the Great Wall to the west, the Songhua River to the north, and the southern part of the Korean peninsula to the south. In addition, the state of Buyeo, of which Jumong had been a prince, is said to have been founded as early as the 7th century BCE rather than the traditionally accepted date of around the 2nd century BCE. Buyeo too was said to have ruled over a huge territory, including the Russian Maritime region to the east, the Amur River to the north, the upper reaches of the Liao River to the west, and the Changbai (Baekdu) Mountains to the south. Also similar to the script of Jumong, North Korean historians interpret the expansion of Goguryeo as an effort to reconstruct the homeland of Gojoseon. Yangjin Pak, “Contested Ethnicities and Ancient Homelands …,” 615-616.

60 N. Harry Rothschild, Wu Zhao: China’s Only Woman Emperor (New York: Pearson Longman, 2008), 5-6.

61 Ahn (2006).

62 However, Jumong was aired in Hong Kong and Taiwan.

63 Joel Martinsen, “Korean History Doesn’t Fly on Chinese TV Screens.”