Korean Forced Laborers: Redress movement presses Japanese government

By Yumi Wijers-Hasegawa

[Following Japan’s unconditional surrender in the Asia Pacific War, Japanese leaders had good reason to expect that the American Occupation would be harsh. GHQ’s initial focus on war crimes prosecutions, purging militarists from public life and dismantling zaibatsu conglomerates, however, soon yielded to “reverse course” policies that emphasized economic recovery and political stability rather than deep democratic reform. The Chinese Communist Party came to power in 1949 and the Korean War broke out in 1950, dramatically altering Northeast Asia’s geopolitical landscape. Consistent with the lenient terms of the San Francisco Peace Treaty in 1951, the United States persuaded its reluctant wartime allies and many of Japan’s former colonies to waive reparations claims against Japan as the US sponsored the former foe back into the community of nations.

By 1965, when the Japan-South Korea Basic Treaty finally normalized relations between the former colonizer and the colonized, Japan’s economy was booming and Tokyo was negotiating from a position of relative strength. Seoul needed financial help for its own economic recovery and was under pressure from Washington to sign an accord. Intensely unpopular with the South Korean public, the treaty’s “economic cooperation” formula transferred $500 million in official loans and grants (along with another $300 million in private loan credits) from Japan to South Korea, but sidestepped bitter issues of responsibility for colonial rule. Near the top of the list were the unpaid wages and other benefits owed hundreds of thousands of Koreans who had been conscripted for military service or labor in wartime Japan. Their claims were waived by the treaty.

Back in 1946, however, the Japanese government and corporations could not have predicted this remarkably favorable string of events. That year the state directed corporations to deposit unpaid wages and related monies with government agencies, and the funds were later commingled with money owed by the state itself to Koreans who had worked for the military. GHQ, in fact, approved these early moves and it was expected that former Korean workers and soldiers, or their families, would eventually receive the salaries and benefits they had earned. They never did. Today the deposits are still being held by the Bank of Japan in the amount of roughly $2 million, unadjusted for six decades of interest or inflation, while most of the soldiers and forced laborers have died.

South Korea’s Truth Commission on Forced Mobilization under Japanese Imperialism, working closely with Japanese activist groups, is currently trying to rectify this injustice and establish a reliable historical record of the entire conscription system and the treatment of forced laborers and draftees. The important article below reveals that the Japanese government assessed the benefits owed to Korean military draftees and, prior to 1965, even included a compensation fund for them in the national budget. As concerned citizens in Japan, South Korea and elsewhere become aware not only of the obligation, but also the fact that Japan once planned to disburse the unpaid wages it now holds, pressure for redress will continue to mount. The Japanese book described in the article is Japan’s Postwar Responsibility Toward Korean Military Draftees and Labor Conscripts.

It is frequently pointed out that Japan has failed to come to terms with the legacy of colonialism and war, and particularly that it has failed to provide adequate apologies and reparations to victims of war crimes and atrocities. What is less often noted is the quiet engagement of many citizens to pursue redress at the societal level and to press the government to do the right thing. Still less noted is the virtual immunity of the United States, both from international pressures and societal pressures, to make amends for its own atrocities and crimes against humanity. There has been no reckoning—or any sustained American or international movement—in response tothe indiscriminate bombing of 64 Japanese cities or the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, still less for the massive bombing of civilians in Korea, Vietnam, Iraq and elsewhere. Bill Underwood]

The government should pay its long-owed obligations to Koreans pressed into military service or labor as stipulated in documents it drew up before 1965, said a citizens’ group pushing the state to accept responsibility for its colonial rule of the peninsula.

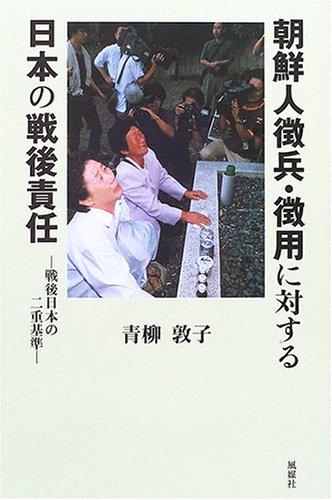

Aoyagi Atsuko (left) shows her books that demand that Japan compensate Koreans pressed into wartime service, as Iwahashi Harumi, who translated them into Korean, looks on.

The group—led by Aoyagi, a homemaker from Miyazaki Prefecture who began supporting several lawsuits in 1990 filed by Koreans pressed into military service or forced labor—published a book explaining the suits in Japanese and Korean last May.

The book also shows copies of documents that indicated plans to pay reparations to the Koreans with direct labor contracts with the state, but which were never put into effect. Not included among them, however, were the thousands of Korean “comfort women” Japan rounded up and forced into sexual slavery for its armed forces. They had no such contracts.

The documents, called “individual investigation charts,” assessed benefits, including bereavement and survivor allowances, and salary arrears for individual Koreans killed during the war.

The group believes the government disclosed the documents to Seoul in 1990, but it was not until recent years that relatives of the dead in South Korea received copies. The documents are also not widely known by Japanese or Koreans.

“My impression (until I encountered the documents) was that the drafted Koreans were treated so badly that they were not even identified as individuals,” Aoyagi said in a recent interview.

“But the documents show Japan was preparing to pay them indemnification,” which was to be equal to that of Japanese who performed the same duty, she said. “I was flabbergasted but happy to find that out.”

Late last year, the group translated the book into English. It plans to take the book to the U.N. Human Rights Commission, along with a petition calling on Japan to compensate the draftees and their survivors.

According to the group, during Japan’s 36-year colonial rule to 1945, about 365,000 Koreans fought for Japan as soldiers and army civilian employees. In addition, about 1 million Koreans were pressed into service as laborers for Japanese corporations and war-related industries.

Although Japan acknowledged that 22,182 Koreans mobilized for the war effort died, it provided no compensation to their next of kin.

Aoyagi found the documents in South Korea in 2004.

The papers say the amount to be paid to a civilian employee of the Imperial army, for example, was equivalent to 5 million yen to 6 million yen, including funeral allowance. The compensation fund was set aside in the national budget.

“As the price of a life, this amount is extremely low, but the government did pay the Japanese. It must also pay the Koreans because it was promised (to them),” Aoyagi said.

According to the group, Japan proposed to pay compensation to individual Koreans based on the charts prior to the 1965 normalization of diplomatic ties with the South.

But the two sides failed to agree on various issues, including the number of victims and the legal basis for the redress. As South Korea, still smarting from the Korean War at the time, made unexpectedly high demands, the talks deadlocked.

In the end, Japan abandoned its plans to pay individual redress and the case was “officially” closed at the government level, with Tokyo paying South Korea a lump sum of $300 million in the form of an economic assistance grant and a $200 million low-interest loan on condition that it not be held liable for individual compensation.

“Koreans were drafted into Japan’s wars by being told they were Japanese. Only Japan can bear this responsibility,” but with the postwar Korean independence, they were “no longer Japanese” and therefore not compensated, Aoyagi said. “Such a double standard is an unthinkable act of betrayal.”

After the economic assistance package was disbursed, Japan put away its charts and fell silent, without explaining anything to individual victims, Aoyagi said.

“Of course, what Japan did to the Koreans is beyond description. But the majority of people, both Koreans and Japanese, don’t even know that the drafted Koreans were paid salaries, and that Japan was planning to indemnify them until 1965,” she said.

Had Japan explained that it had once considered paying compensation for the individuals, the animosity Koreans feel might not have been as deep as it is now, Aoyagi said.

YUMI WIJERS-HASEGAWA is a staff writer for The Japan Times. This article appeared in The Japan Times, February 17, 2006. Posted at Japan Focus on February 23, 2006.

William Underwood is the author of two Japan Focus Reports on Chinese Forced Labor and Japanese government and corporate resistance to reparations, available here and here.