Korean Prisoners-of-War in Hawaii During World War II and the Case of US Navy Abduction of Three Korean Fishermen

Yong-ho Ch’oe1

University of Hawaii at Manoa

Introduction

Although there has been much attention given to the Japanese-Americans who were detained in the infamous detention centers of Hawaii and throughout the Western United States during World War II, virtually nothing is known about the Korean prisoners-of-war (POWs) in Hawaii in the years 1943-45. Approximately 2,700 Korean POWs were captured and brought to the Island of Oahu, where they were incarcerated until the end of the war and their repatriation to Korea in December 1945. This is a preliminary report on these Koreans based on limited data I have uncovered in the hope that other interested scholars may more fully document their experience in the future.

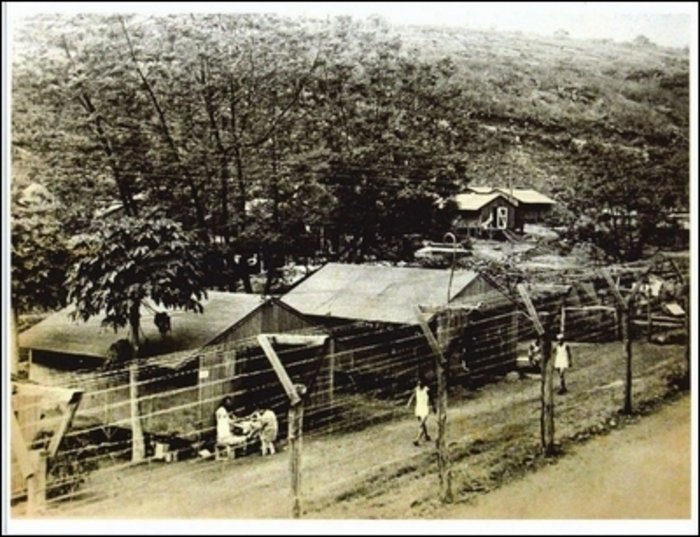

Plucked mostly from various Pacific islands toward the end of the war, these Korean POWs were detained in a camp in Honouliuli on the Island of Oahu. This camp, located in Honouliuli Gulch, west of Waipahu, was opened in March 1943 as the Honouliuli Internment Camp to detain Japanese and Japanese-American internees as well as POWs from Japan, Italy, and elsewhere. It was later renamed as Alien Internment Camp and still later as POW Compound Number 6.2

Honouliuli Camp

This camp is remembered as the detention site on Oahu that incarcerated a number of Hawaii residents of Japanese ancestry in flagrant violation of their basic human and Constitutional rights. Initially, an internment camp was established on Sand Island on Oahu right after the Pearl Harbor attack in December 1941. But with the arrivals of a large number of POWs from Italy and Japan, and with the need to move away from possible direct enemy attack, a new larger camp was set up at Honouliuli Gulch to accommodate them.

With an area of 160 acres, the Honouliuli Camp could initially accommodate approximately 3,000 internees and POWs. The camp was divided into several barbed wire enclosures to segregate various types of occupants, divided largely into two groups—civilian internees and POWs. Enclosures for Japanese internees were separated by fence according to their gender, indicating that, unlike those in mainland internment camps, the Hawaii internees were separated from their family members. As if to underscore their racist sentiment, the United States military authorities set up a separate enclosure for the small number of white civilian internees—Germans and Italians—with separate kitchen, mess hall, and toilet facilities. These internees were segregated from Japanese POWs, who were detained in separate barbed wire enclosures within the camp.3

Noncombatant Laborers

We do not know when the first Korean POWs arrived in Hawaii. In August 1943, Colonel Erik de Laval, a Counselor at the Legation of Sweden, Washington, D.C., inspected the Honouliuli camp in accordance with the Geneva Convention and reported that there were 229 internees (69 Japanese nationals and 160 Japanese-Americans internees) and two Japanese POWs. There is no mention of any Koreans in this report.4

The first arrivals of Korean POWs to the Honouliuli camp must have come in late 1943 or early 1944 as the following report suggests: “As a result of the Gilbert Island operation and the capture of Korean noncombatant prisoners of war, it has been found necessary to construct an additional enclosure to separate the Japanese from the Koreans.”5 From this report, we learn that an unknown number of Korean noncombatant POWs were brought to the Honouliuli camp after the Gilbert Islands operation and that an additional enclosure was built to accommodate these Koreans.

The military operation on the Gilbert Islands took place in November 1943. In the first counteroffensive against Japan, the United States Navy and Marines launched an attack against the Gilbert Islands, meeting fierce resistance from the Japanese defenders resulting in heavy casualties on both sides.

The initial attack targeted Makin Atoll, where the Japanese military maintained a garrison of 798 men. Shortly after landing, the Americans captured about 35 Korean laborers as prisoners, and when the operation was completed, a total of 105 POWs were taken, all but one of whom were noncombatant laborers. All these POWs except one were most likely noncombatant Korean laborers mobilized by the Japanese. Among the 798 men on the Japanese side on Makin Atoll, there was one labor unit consisting of 276 men “who had no combat training and were not assigned weapons or a battle station,” according to one report.6 It is believed that most, if not all of them, were Korean. If this is true, out of 276 Korean noncombatants, only 104, less than half, survived as prisoners while 172 died in the fighting.7

The Gilbert Islands Operation then turned against Tarawa Atoll, where more than 4,700 defenders, including 1,200 Korean laborers, were stationed.8 After four days of fierce combat, the atoll was brought under American control. The total Japanese and Korean casualties were reported to be 4,713. The only survivors were one Japanese officer, 16 enlisted men, and 129 Koreans who were taken as POWs.9 This means that out of 1,200 Korean noncombatant laborers on Tarawa, only 129 survived as POWs and nearly 1,000 died in battle.

These Korean POWs—129 from Tarawa and 104 from Makin—were believed to have been brought to the Honouliuli camp, which necessitated the construction of an additional enclosure as stated in the report cited above.

Colonized by Imperial Japan after 1910, Koreans were actively mobilized to contribute to Japan’s war cause, especially after the Pearl Harbor attack in 1941. In addition to tens of thousands of Koreans who were conscripted into the Japanese Imperial Army, a large number of noncombatant Koreans were mobilized to work as manual laborers for construction works and others for Japanese military bases and facilities on various islands scattered throughout the Pacific Ocean under Japanese control. Given no military training and issued no weapons, they were noncombatant civilian workers. The Gilbert Islands operation exacted an extraordinarily high rate of casualties among the Korean laborers in the service of Japanese imperial ambitions—more than half on Makin and nearly nine out of ten on Tarawa.

In addition to these Korean POWs from the Gilbert Islands, some 300 to 400 Korean laborers were brought to the Honouliuli camp after the American military operation on Saipan in 1944. In a telephone interview I conducted with Mr. Young Taik Chun, a second generation Korean-American, on October 27, 1990, he stated that in July or August of 1944 the United States military authorities asked him to interpret for Korean POWs at the Honoulilui camp, who had just been brought from Saipan. When he arrived at the camp, there were 300 to 400 Koreans, all of them noncombatant laborers, who had recently been transported from Saipan. According to Mr. Chun, a number of these Koreans were wounded and required medical attention, often hospitalization. Most of their wounds had been inflicted by Japanese troops through beating, sword and knife slashing, and other abuses. He saw a dozen or so with severe wounds caused by Japanese swords. Some had bullet wounds from the battle as the Americans tried to take control of the island. This report suggests blatant abuses by the Japanese military against Korean noncombatant laborers on Saipan.

As is well known, Saipan was the scene of one of the most ferocious fights as the Japanese fought to the very last man rather than surrendering. In the end, almost the entire Japanese garrison on the island—at least 30,000—perished along with about 22,000 Japanese civilian deaths.10 It is believed that a significant number of the 22,000 civilian deaths were Korean noncombatants (precise numbers are not available). Many civilians were forcibly driven to death by the Japanese, some jumping from “Suicide Cliff” and “Banzai Cliff.” Apparently only 300 to 400 Koreans survived on Saipan and were brought to the Honouliuli camp, as my witness testified.

It is likely that Korean laborers from various other Pacific islands, such as Guam, Tinian, Palau, and Peleliu were also brought to the Honouliuli camp as POWs, having experienced similar ordeals.

On September 26, 1945, The Honolulu Advertiser carried an article under the title “Fraternization Problems Here With Enemy War Prisoners.” It says:

Italians who number 4,841 and the 2,607 Koreans are most easily managed and cleanest prisoners, the former because they were trained to be topnotch soldiers and the latter because of natural racial characteristics and their relief through the Allies from Japanese oppression.

The Advertiser article provides a glimpse of the life of POWs within the camp, noting that the prisoners were shown a movie once a week and that soccer was a favorite game. It goes on: “Koreans are building a stage from scrap lumber where they plan to present their own plays and conduct their political campaign.” The camp also offered classes in English and, according to this report, the Koreans “who were extremely pro-Allies, were the most interested and best pupils.”11

A United States military report, dated July 28, 1945, states that 2,592 Koreans were detained in Hawaii with the following distributions:12

Compound No. 7 874

Compound No. 8 25

Compound No. 9 469

Compound No. 11 91

Compound No. 12 95

Compound No. 13 997

Hospital 41Total 2,592

This number increased to 2,700 by December 1945 when a complete list of the Korean POWs of the Honouliuli camp was made just before they were repatriated to Korea. A copy of this list in my possession gives names and home addresses, grouped according to provinces and counties of origin.

While in the camp, all Korean POWs received a monthly allowance of three dollars. If one performed extra work such as laundry, carpentry, etc., he was paid 80 cent a day more. The POWs were also allowed small lots where they could grow vegetables and flowers. Apparently, they did no work on behalf of the war effort. Since the prisoners were free to use or save their money as they wished, many volunteered to work, according to one former POW.13 They took their savings home when they returned to Korea. Dr. Nam-Young Chung, who served as an officer in the United States Military Government in South Korea in 1945-1948, told me in a recent interview that he personally helped several Koreans who had returned from Hawaii to cash American checks they had received at the Honouliuli POW camp.14

Three College Draftees (Hakbyŏng)

We learn very little about these Korean POWs until the arrivals of three Koreans—Pak Sundong, Yi Chongsil, and Pak Hyŏngmu—who came to the Honouliuli camp shortly after the end of the war. The so-called “student draftees” (Hakbyŏng in Korean and Gakuhei in Japanese), they were conscripted into the Japanese Imperial Army while they were enrolled in colleges in Japan. One of them, Pak Sundong, wrote a memoir detailing his life under the Japanese military, his desertion to the Allied powers, and his eventual work for the U.S. Office of Strategic Services (OSS) until the end of the war, at which time he was sent to the Honouliuli camp. His award-winning memoir appeared in a monthly magazine in Korea, Sin Tonga, in September 1965 under the title of “Momyŏl ŭi sidae” (An era of humiliation). Briefly, this is how he wound up in Honouliuli.

Three College Draftees. From left to right: Yi Chongsil, 31, Pak Hyŏngmu, 24, and Pak Sundong, 25

Drafted into the Japanese army in January 1944, along with his friend Yi Chongsil, he was sent to the frontline in Burma in June of that year where his unit engaged in fierce combat against the British. In March 1945, motivated by ardent Korean nationalist sentiment, Pak and Yi made a daring escape from the Japanese army and surrendered to the British. The two Koreans were sent to a POW camp in New Delhi, India, where they were kept along with other Japanese captives. In a daily morning exercise, all the Japanese POWs bowed toward Tokyo, pledging undying loyalty to the emperor. When the two Koreans remained erect refusing to bow, their conspicuous action drew attention from English guards, who separated them from the Japanese, at last recognizing their Korean identity. In this Korean enclosure, the third Korean—Pak Hyŏngmu (who also had deserted and surrendered)—joined them a week later.

After tough interrogation, the three were introduced to two American sergeants surnamed Ch’oe and Kim, Korean-Americans, who spoke to them in Korean. Pak Sundong described this encounter: “I felt as if I had met the Buddha in hell.” After more questions testing their Korean nationalistic determination, they were asked if they were willing to work for the American war cause against Japan, risking not only their lives but also the safety of family members back home in Korea. As fervent Korean nationalists, they expressed their willingness to work for the United States and the Allies. Asked about the risks his family members back in Korea, he responded: “Most Koreans wish to be free from Japanese suppression. Accordingly, even if my family members were to suffer persecution as a result of my work for the Allied powers in behalf of my fatherland, they would not resent me. I will surely fulfill my missions [for the Allied Powers].”15

Having agreed to work with the Allies to defeat Imperial Japan, all three Koreans were transported to unknown destinations and told not to question where they were going. Eventually they were taken to Santa Catalina Island, off the California coast, where they began intensive military training as special agents of the OSS. Secret preparations were underway to land troops on the Korean Peninsula—now known as the NAPKO Project—before invading Japan. While the three former Korean draftees were training for this operation, the war came to an end when Japan formally surrendered in August 1945. Overnight, the status of these Koreans shifted abruptly from OSS special agents to POWs. To their great dismay and indignation, they were unceremoniously put into POW uniforms once again and confined to a barbed-wire enclosure. Their bitter protests against U.S. officials for betraying their trust and cooperation–they were prepared to risk their own life for the American cause–even resorting to a hunger strike, were of no avail. They were sent to Hawaii as POWs.16

Soon after their arrival at Honouliuli, Colonel H. K. Howell, the commanding officer of the camp, invited them to a meeting, where he tried to assuage their bitter sentiment, expressing his deep sympathy with the Koreans. (Howell’s female secretary was Sin Yŏngsun, a second generation Korean-American, who interpreted for them and assisted greatly on their behalf despite her limited command of the Korean language.)17

According to Pak Sundong’s observation, the Korean POWs in the camp in general were not well disciplined and frequently conducted themselves without consideration for others. At the suggestion of Colonel Howell, the three former OSS agents started a program for Korean POWs to foster the spirit of self-reliance and self-governance toward building a democratic country. They published a Korean-language newsletter for fellow Korean POWs.18 Handwritten and mimeographed, the newsletter carried the Korean title of Chayu Han’in-bo along with the English title of Free Press for Liberated Korea. While emphasizing the idea of freedom, the newsletter maintained an editorial tone of Korean nationalism with a logo of the Korean National Flag in three colors in each issue. It tried to instill “the idea of independence and freedom which we all seek ardently.”19 Insulated from the outside world, the Korean POWs had nothing to read except some English publications provided by the United States military authorities, which most could not understand. In the newsletters, the three Hakbyŏng translated English articles appearing in Reader’s Digest and national and local English newspapers to inform and enlighten fellow Koreans about events in the outside world.

For example, newsletter No. 3 carried an abstract translation of William Hard’s article, “Way to Peace: How the United States Should Understand the Soviet Union,” which appeared in Reader’s Digest in September 1945. Another article is a digest of an article written by Ogden M. Reid, the editor of The New York Herald Tribune, who wrote after visiting China, Manchuria, Korea, and Japan. Reid said that Korea, having experienced Japan’s tyrannical rule for 40 years, had no alternative but to continue to utilize Japanese technical specialists until Koreans could be trained to run their own industry. It also drew on local newspapers in Hawaii to report on the international situation, such as the Soviet occupation of Manchuria and the impending conflict between the Chinese Nationalists and Communists, as well as on proposals to place atomic bombs under international supervision—all major current global issues.20

To instill national pride and confidence, Free Press for Liberated Korea carried several articles on Korean history emphasizing its proud achievements, such as Silla’s ch’ŏmsŏngdae (astronomical tower), Koryŏ’s ceramic works, and Han’gŭl (Korean Alphabet). In its last issue, No. 7 dated December 12, 1945, breaking its rule of allowing only Korean POWs to write for the newsletter, it included an article written by Hyŏn Sun (Soon Hyun), a prominent Korean nationalist leader and a Methodist minister who sought refuge in Hawaii after 1923.

Empathizing with the Korean POWs for the suffering they had experienced under Japanese rule, the elderly Korean nationalist bid farewell to them as they were anticipating repatriation and urged them to work to build a new Korea.21

It also distributed a photo of American commanders as well as one of Syngman Rhee (Yi Sŭngman) as individuals whom the POWs should respect. The caption on Syngman Rhee’s portrait reads:

Dr. Syngman Rhee, along with his comrades, has dedicated his life and property toward the freedom and independence of our motherland Korea. Dr. Rhee has spent the life of an exile for many years leaving his homeland. During his exile, he argued with the Allied Powers on behalf of Korea’s freedom and independence and became prominent in the United States. Before Korea’s liberation, he became a representative of the Korean Provisional Government, of which the United States governmental and political leaders became cognizant. As Korea moves toward independence, Dr. Rhee’s talent and ability draw special attention.

Rhee’s position as a nationalist leader was recognized through the newsletter by the three former students among the Korean POWs.

Hoping to attract a wide readership among the POWs, the troika printed 1,350 copies of the newsletter every week—one copy for two men. But, to their great disappointment, they found the bulk of their painstaking work discarded in trash cans unread. Although the editors tried to understand the fact that a large majority of fellow Korean POWs were uneducated laborers, the troika nevertheless were unhappy to find their labor of love little appreciated by their fellow countrymen.22

The Korean POWs organized many social organizations. Based on their origins, they formed provincial as well as county associations. In addition, they maintained associations based on respective clan lineages (Chongmunhoe). These organizations, however, were not necessarily conducive to the overall unity and harmony of the Korean POWs, according to Pak Sundong. Often, Pak said, they bad-mouthed other groups causing animosity and factional strife within the camp.23

The POWs discovered a simple way to brew alcohol. They learned that if you simply add yeast to strawberry jam, overnight it became spirits, which they imbibed as their favorite makkŏlli drink.24 As the Honolulu Advertiser reported above, soccer was their favorite sport, and they competed with Italian POWs on Sunday, November 11, 1945 before a cheering crowd of more than 600 onlookers. In spite of spirited effort and team work, the Korean team lost 5-3.25 At this game, by chance, Pak Sundong met To Chinho (Chin-Ho Tough, Jin-Ho Do), a Korean resident of Honolulu, among the crowd. This encounter was an emotional one as Pak learned that To was a fellow hometown senior from Sunch’ŏn in Chŏlla Province,26 who had moved to Hawaii in 1931 as a Buddhist missionary and played an active role in the Korean nationalist movement. (He worked as an editor of T’aepyŏngyang chubo, also known as Korean Pacific Weekly in English, and later was a founding member of the United Korean Committee, one of the most important Korean organizations in the United States.)27

Who was Pak Sundong, who gave us a valuable glimpse of the lives of Korean POWs? Little was known about him, except through his article “Momyŏl ŭi shidae”, until the 1980s publication of Cho Chŏngnae’s monumental ten-volume novel, T’aebaeak sanmaek (T’aebake Mountain Range). An epic novel detailing a saga of a turbulent era ridden with political, social, and economic upheaval in southwestern Korea on the eve of the outbreak of the Korean War, T’aebaek sanmamaek broke the ideological taboo that had prevailed for decades and has since become one of the all-time best sellers in South Korea exercising enormous influence on the political and social consciousness of post-Korean War generations. (In my view, it may well be the greatest novel written in Korean.) Among the most important characters in the novel is Kim Pŏmu, an intellectual who maintained integrity, sanity, and conscience through troubled times. Cho Chŏngnae has acknowledged that he modeled Kim Pŏmu after Pak Sundong and that Pak is his uncle (a younger brother of Cho’s mother).28 Through Cho Chŏngnae’s masterpiece, one gets a glimpse of the kind of life Pak Sundong might have led in South Korea after returning from Hawaii, and his world view, it should be noted, was obviously influenced by his experiences as a former student draftee, an OSS agent, and a POW cellmate at the Honouliuli camp. Thus, one of the Korean POWs in the Honouliuli camp emerged as a major figure in modern Korean literature.

Three Fishermen

One of the last acts as POWs of the Korean troika was to make a list of all the Koreans in the camp. It appeared as an appendix to the last issue of their newsletter, No. 7, dated December 15, 1945. Among those listed, three men, Kim Tŏkyun, Kim Kich’an, and Ch’oe Kŭmbong, deserve special mention. We learn that a US submarine kidnapped at gun point three Korean fishermen from the southern coast of Korea and brought them to the United States. Briefly this is what happened.

The war situation in early 1945 was grim for Japan, and the U.S. Navy carried out submarine operations along the southern coast of Korea with virtual impunity. On April 6, 1945, an American submarine, Tirante, surfaced in the calm sea near Samch’ŏnp’o (in South Kyŏngsang Province) where numerous Korean boats were fishing. The Tirante attacked one of the larger boats, capturing its crew and taking them back to a base. The Americans wanted information on the suspected anchorage at Yŏsu Bay. The capture of the fishermen is depicted in the Tirante’s patrol report:

[At] 1918 [7:18 pm] Surfaced, going after one of the larger schooners.

[At 1930] [7:30 pm] Having trouble coming alongside, and he isn’t cooperating. Fired a 40-mm shell through his mainsail. The shell exploded, making a big hole in the sail; a 30-cal. machine gun cut his mainsail halyard so he lowered his sails in short order.

[At] 1949 [7:49 pm] Boat alongside. We look huge by comparison. Lt. Endicott PEABODY II (All American, Harvard 1942) and SPENCE, H.W. GMlc [sic] jumped aboard, both armed to the teeth in terrifying fashion . . . . With many hoarse shouts and bursts of tommy gun fire, three thoroughly scared and whimpering fishermen were taken aboard.29

The three fishermen were abducted to the United States.

Although Korea at the time was under colonial rule of Imperial Japan, which was at war with the United States, these fishermen were engaged in utterly peaceful work. The American submarine attacked the unarmed fishing boat, seized its crew and took them from their homes. The three fishermen from Samch’ŏnp’o were Ch’oe Kŭmbong, age 42; Kim Tŏkyŏng, 43; and Kim Kichang, 44. They were brought to Pearl Harbor for interrogation. As fishermen they had little knowledge of military affairs. The interrogation report says: “POWs were generally ignorant of military information, but they are able to list and describe areas in Korean water which were restricted to all.”30 The three are included in the list POWs at Honouliuli.31

A recent Korean TV documentary, “MBC Special Documentary,” showed interviews with elderly people in Samch’ŏnp’o, which verified the story of their abduction. Yang Kŭmjŏng, a step-daughter of Kim Tŏkyun, in particular recalled vividly the story she had heard from her step-father after he returned home from the United States.32

Horace G. Underwood, later a prominent American missionary educator in Korea, was a Naval intelligence officer stationed at Pearl Harbor interrogating POWs during the war. He writes in his memoir:

I remember one group of three fishermen from Samchonpo on the South coast. After their boat was sunk by a sub, they were brought to Pearl. On questioning, I learned that the skipper had once been as far as Pusan, but the other two had never been outside Samchonpo, except for fishing. What a change to go out one morning and end up at Pearl Harbor!33

Underwood’s complacent account verifies the abduction of the fishermen peacefully engaged in daily work by the US Navy.

In 2002, North Korea, after denying it for many years, finally confessed with apology that its secret agents had kidnapped more than a dozen Japanese citizens and taken them to North Korea in the 1970s. The North Korean objective was to use these Japanese for training North Korean spies. When the North Korean admission was announced in Japan, there was outrage to the point of forcing the Japanese government to halt its diplomatic dealings with North Korea. Indeed, that outrage has governed Japanese policy toward North Korea ever since. Long before North Korea’s kidnapping, the United States committed a similar act, equally outrageous and reprehensible. The American abduction of three Korean fishermen deserves no less condemnation by the American public. Though late, the United States Navy and the United States government should offer an official apology as well as appropriate compensation to the families of these fishermen.

Conclusion

This is only a brief glimpse into the profiles of the Korean POWs detained in the Honouliuli camp based on preliminary research. As noted, almost all of the 2,700 Korean POWs were noncombatant laborers.34 They also included three former college students, who, after deserting the Japanese military and working with the OSS, were themselves imprisoned as POWs. Then, there were three fishermen, who were abducted at gun point by the crew of a submarine home ported at Pearl Harbor. These POWs were all tragic victims of the war.

To the general public in Hawaii, the Honouliuli camp is largely remembered as an internment center where Japanese-Americans were illegally incarcerated during the war. Presently the Japanese Cultural Center of Hawaii is leading a campaign to clear the camp area (now covered with heavy vegetation) and establish a memorial for those Japanese-Americans who were unjustly incarcerated. This is indeed a laudable move so that the future generations will be reminded that such an act of unconstitutionality and inhumanity should never be repeated on this land.

In building such memorial, we should not forget that the Honouliuli camp also detained 2,700 Korean POWs. The Korean POWs included three former college students who were drafted into the Japanese military and deserted to the Allied Powers and worked as special agents of OSS of the United States only to be reduced to POWs at the end of the war. They also included three fishermen who were kidnapped from Korean waters and were incarcerated in the Hawaii POW camp. They too were innocent victims of immoral and illegal acts perpetrated in the name of war. A similar memorial should mark the presence of Korean POWs at Honouliuli.

To be sure, ethnic Koreans and ethnic Japanese in Hawaii in general maintained unfriendly, if not downright hostile, sentiment toward each other throughout the war. Fortunately, such feeling has largely dissipated. In a new spirit of reconciliation and cooperation, the two Asian ethnic groups along with others in Hawaii should work together to establish a monument (and memorials as appropriate) to remember those victims of the war.

Yŏng-ho Ch’oe is professor emeritus of history at University of Hawaii at Manoa. He has written extensively on pre-modern and modern Korea history and co-edited “Sources of Korean Tradition” and “Sourcebook of Korean Civilization.

Recommended citation: Yŏng-ho Ch’oe, “Korean Prisoners-of-War in Hawaii During World War II and the Case of US Navy Abduction of Three Korean Fishermen,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 49-2-09, December 7, 2009.

Notes

1 I wish to acknowledge gratefully the kind assistance and cooperation given by Jeffery F. Burton of Trans-Sierran Archaeological Research, Tucson, Arizona, and Brian Niiya and Betsy Young of Japanese Cultural Center of Hawaii.

2 Jeffery F. Burton and Mary M. Farrell, “World War II Japanese American Internment Sites in Hawai’i” (December 2007), 63.

3 Territory of Hawaii, Office of the Military Governor, Iolani Palace, Honolulu, T.H., “Control of Civilian Internees and Prisoners of War in the Central Pacific Area.” (Undated.)

4 A copy of this report is in the Japanese Cultural Center of Hawaii Research Center, Honolulu, Hawaii.

5 Territory of Hawaii, Office of the Military Governor, Iolani Palace, Honolulu, T.H., “Control of Civilian Internees and Prisoners of War in the Central Pacific Area.” (Undated)

6 Link

7 See also this link.

8 It is possible that the Japanese defenders may also have included Korean soldiers conscripted into the Japanese Imperial Army, separate from the Korean laborers, but we have no information on this during the Gilbert Islands operation.

9 Link. The Tarawa battle exacted a heavy toll on the US Navy and Marines with 1,677 dead. Writing after the war, General Holland M. Smith, who commanded the Marines stated: “Was Tarawa worth it?” “My answer is,” he said “unqualified: No. From the very beginning the decision of the Joint Chiefs to seize Tarawa was a mistake and from their initial mistake grew the terrible drama of errors and errors of omission rather than commission, resulting in these needless casualties.” Ibid.

10 Link. These figures for “Japanese” may well have included a significant, but indeterminate, number of Koreans, both in the ranks of the military and laborers.

11 “Fraternization Problem Here With Enemy War Prisoners,” Honolulu Advertiser, September 26, 1945.

12 “Statistical Data Report For Prisoner of War Base Camp HPU 950, 28 July 1945.”

13 Testimony of Kim Han’ok, a former member of the Honouliuli camp, given to Dr. Do-Hyung Kim, “T’aep’yŏng chŏnjaeng ki Hawaii p’oro suyongso ŭi Han’in chŏnjaeng p’oro yŏn’gu (A study of Korean POWs in a Hawaii POWs detention center during the Pacific War) (Unpublished report).

14 My interview with Dr. Nam-Young Chung was conducted on April 10, 2009.

15 Pak Sundong, “Momyŏl ŭi sidae (An era of humiliation),” Sin Tonga (September 1965), 372-73.

16 Ibid., 373-81.

17 Ibid., 382-83.

18 Ibid., 383.

19 Chayu Han’in-bo, No. 7 (December 12, 1945).

20 Ibid., No. 3 (November 15, 1945).

21 Ibid., No. 7.

22 Pak Sundong, 383.

23 Ibid., 384.

24 Ibid., 382.

25 Ibid.. 384.

26 Pak Sundong, 384.

27 My interview with Mr. To Chinho took place on July 5, 1978.

28 Kwŏn Yŏngmin, T’aebak samnaek tasi ilki (Re-reading Taebaek sanmaek) (Seoul: Haenam, 1997), 50.

29 Edward L. Beach, Submarine! (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1952), 270. Peabody was later Governor of Massachusetts.

30 An interrogation report in the National Archive, Maryland, as shown in “MBC Special Documentary” (whose telecast was monitored in Honolulu on March 7, 2009).

31 Ch’oe Kŭmbong is listed in an interrogation report in the National Archive, Maryland, as Ch’ae Kŭmpong. (See “MBC Special Documentary.”) I believe these two names refer to the same person.

32 Ibid.

33 H. G. Underwood, Korea in War, Revolution and Peace: The Recollections of Horace G. Underwood (Seoul: Yonsei University Press, 2001), 91

34 Since a large number of Koreans were conscripted into the Japanese Imperial Army and were dispatched to the Pacific islands, it is possible that some of these Korean soldiers may have been captured as POWs and brought to the Honouliuli camp. But we have no information so far on this aspect.