New Era for Japan-Korea History Issues: Forced Labor Redress Efforts Begin to Bear Fruit

William Underwood

Historical issues involving

President Lee Myung Bak has said he “does not want to tell

Yet the tough stance of the previous president, coupled with vigorous cross-border activism involving South Korean and Japanese citizens, has begun yielding results.

On January 22, the remains of 101 Korean military conscripts killed in nearly a dozen countries were returned to

During the Yutenji memorial ceremony, a Japanese government representative expressed “deep remorse and apology” for suffering inflicted upon Koreans under Japanese colonial rule from 1910 to 1945, quoting from the written apology offered by former Prime Minister Obuchi Keizo to former President Kim Dae Jung in 1998.

Access to the main ceremony, however, was tightly restricted by the Japanese government. Media personnel, members of Japanese activist and religious groups, and even a current Japanese Diet member were barred from attending.

Memorial services for Korean remains repatriated from

Returning Korean military conscript remains has been a fitful, decades-long process.

This helped to derail the remains repatriation process within

Former Prime Minister Koizumi Junichiro promised former President Roh at their December 2004 summit meeting that

Roh stated that

Public hearings held across

Last fall the Truth Commission on Forced Mobilization reported that Yasukuni Shrine has inaccurately listed the names of 60 Koreans among the rolls of Imperial Japanese war dead. Forty-seven of the Koreans were confirmed to have died after World War II, but 13 are still alive. Shrine officials, however, refuse to remove the names of individuals once they have been enshrined. Yasukuni received the names of Korean military fatalities from the Japanese government, which never attempted to notify Korean families of their relatives’ fates.

Guided by local Japanese activists, Korean truth commission members have also conducted fact-finding investigations at former mines and construction sites across

The Japanese government claims, despite much historical evidence to the contrary, that the state was never directly involved in labor conscription by Japanese companies. On this basis,

In addition to the Yutenji bones, some 2,000 sets of civilian Korean remains have been located in Japanese temples and charnel houses since 2005, following a Japanese government request to corporations, municipalities and religious bodies to supply information. Hundreds of the remains may belong to forced laborers who died during the war. But most probably belong to Koreans who died before or after the conscription years (1939-1945) or were not labor conscripts; the latter category would apply to perhaps two-thirds of the two million or so Koreans in

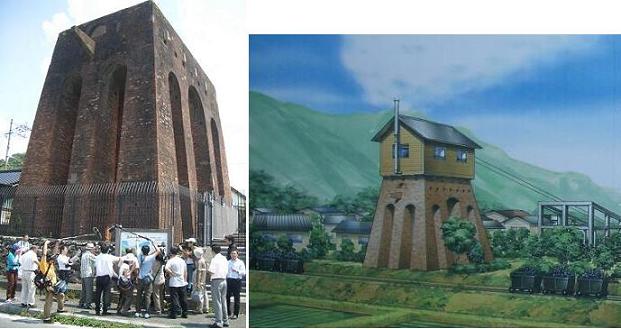

Left: Community researchers in August 2006 describe a former Mitsubishi coal mine in Iizuka,

The Roh administration in 2005 made public all 35,000 pages of diplomatic records involving the 1965 treaty that normalized relations with Japan, setting a new regional standard for information disclosure. The accord provided

In response, Roh spearheaded the passage in November 2007 of a law granting compensation from South Korean coffers to individual victims of wartime forced labor. The measure will provide just over $20,000 to families of military and civilian conscripts who died or went missing outside of Korea; conscripts who returned to Korea with disabling injuries; and families of conscripts who returned to Korea with injuries and died later. Payouts are expected to begin in May 2008.

In addition to fixed-amount compensation, the new law also calls for the South Korean state to make individualized payments to former conscripts and families based on financial deposits now held by the Bank of Japan (BOJ)—money that forced laborers earned but never received. The 60-year-old deposits consist largely of unpaid wages, pension contributions, and death and disability benefits for both civilian and military conscripts.

Partly to discourage Koreans from fleeing worksites in wartime

Wages for Korean soldiers and support personnel conscripted into the military were similarly deposited into postal savings accounts during the war. Japanese authorities deposited salary arrears and related benefits for Korean (and Taiwanese) military conscripts into the BOJ in February 1950.

It has only recently become clear that the Japanese government prior to 1965 made extensive preparations to compensate the families of Koreans killed while serving with the armed forces, even earmarking funds for this purpose in the national budget. Likewise, the original intent of the civilian deposit system was to disburse to workers the funds they had earned. The final form of the normalization treaty, however, sidestepped the question of compensating individuals for conscription and recast reparations as a purely state-level diplomatic issue. The South Korean government was aware, at least in a general sense, of

The Koizumi administration conceded in response to Diet questioning in 2004 that the Bank of Japan continues to possess more than 2 million yen in financial deposits related to Korean labor conscription. The deposits could be worth $2 billion today, if adjusted for six decades of interest and inflation. Japanese courts have confirmed the existence of wage and pension deposits in individual cases, while ruling that the 1965 treaty nullified the rights of Korean plaintiffs to claim the money. Judges have also found that the Japanese state never notified or attempted to notify ex-conscripts or families about the deposits, even when it would have been possible to do so.

The future status of these financial deposits, which remain shrouded in secrecy and are virtually unknown to the Japanese public, represents a major piece of unfinished reparations business.

At a state-level conference last December, Japanese officials reportedly supplied their Korean counterparts with name rosters and, for the first time, financial deposit information for 11,000 military conscripts.

This double standard is consistent with

Neither is the Japanese government helping to send the bones of civilian conscripts home to

Repatriation of all civilian conscript remains in

A Fukuoka-based citizens group called the Truth-Seeking Network for Forced Mobilization was formed in 2005 to facilitate the work of the South Korean government’s truth commission within

Identifying the bones of Korean forced laborers exhumed in August 2006 from a field in Sarufutsu village,

Beginning in 1991, dozens of compensation lawsuits have been filed in Japanese courts against private companies and the Japanese state for civilian and military conscription. Related litigation demanding apology and compensation has involved Koreans who were forced into military sexual slavery, exposed to the atomic bombings, killed in the Ukishima-maru accident, convicted of Class B and C war crimes, abandoned on

Virtually all of these legal efforts have failed due to the claims waiver language in the Japan-South Korea treaty and time limits for filing claims. A decision by the Toyama District Court in September 2007 was typical. Judges dismissed the suit by elderly female plaintiffs, but agreed that as teenagers they had been threatened or deceived into going to

In an unprecedented ruling in November 2007, the Japan Supreme Court found that the government’s refusal to provide health-care benefits to A-bomb survivors living overseas is illegal, and ordered the state to pay damages. The top court confirmed that the plaintiffs had been forcibly taken from

More than 600 elderly Koreans were moved—at Japanese expense—from Sakhalin to

The tens of thousands of Korean “comfort women” represent an egregious class of forced labor outside the formal conscription system. In operation from 1995 to 2006, the Asian Women’s Fund (AWF) was a landmark initiative by Japanese standards of postwar responsibility, extending prime ministerial apologies and compensation from private sources. But only about 300 women across

Last year former Prime Minister Abe Shinzo suggested that comfort women had not been forced into providing sex for

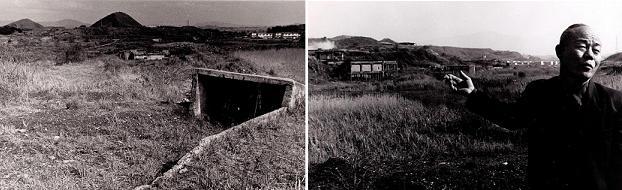

Late 1970s photos of the former Akasaka coal mine in Fukuoka operated by Aso Mining, the family firm of previous Japanese Foreign Minister Aso Taro, and a Korean forced to work there during the war. Aso Mining used an estimated 12,000 Koreans, as well as 300 Allied prisoners of war, for forced labor. (Hayashi Eidai photos)

President Lee Myung Bak vowed during his election campaign to roll back key features of the past ten years of liberal leadership in

Lee himself was born in

The global trend toward repairing historical injustices offers few parallels for the recent direct involvement of the South Korean government in redress efforts targeting a neighboring democratic state. Japanese and Korean civil society actors will try to maintain the momentum of the Roh years and continue healing the scars of forced labor. The effect upon Japanese-Korean reconciliation of Lee’s weaker commitment to reparations remains to be seen.

William Underwood, a faculty member at Kurume Institute of Technology and a Japan Focus coordinator, completed his doctorate at

Note on Sources

Much of this article is based on unpublished information obtained from the Kyosei Doin Shinso Kyumei Nettowaku (Truth-Seeking Network for Forced Mobilization), a Japanese group comprised of leading academic historians and community-based researchers. The Truth-Seeking Network cooperates closely with citizens groups in

Related Articles

William Underwood, “Names, Bones and Unpaid Wages: Reparations for Korean Forced Labor in

Yumi Wijers-Hasegawa, “Korean Forced Laborers: Redress Movement Presses Japanese Government”

Wada Haruki and Gavan McCormack, “The Comfort Women, the Asian Women’s Fund and the Digital Museum”

Korean Overseas Information Service, “Hundreds of Ethnic Koreans from Sakhalin to Return Home”