What is Japanese Tradition?

By Umehara Takeshi

[Debate continues in Japan on how to address what is widely felt to be a long-continuing economic, political, and social malaise. One set of prescriptions would be to return to the values of the prewar era, in particular those of the Meiji Constitution and Rescript on Education (1889 and 1890), believed by some conservatives to be “more” Japanese than the Constitution and Fundamental Law of Education that were adopted under the US occupation and came into operation in 1947. Here, Umehara Takeshi, one of Japan’s best-known scholars of philosophy and religion and himself a prominent conservative, takes issue with such a view. Japan Focus]

Nowadays some people argue that the Fundamental Law of Education [1947] should be revised, because it does not spell out respect for Japanese tradition, and after that the constitution too should be revised. It is unclear how these individuals perceive tradition, but it seems that they see the Imperial Rescript on Education [1890] as something rooted in Japanese tradition, and believe that the Japanese will become fine, moral people if moral education rooted in the spirit of this Rescript is implemented. But is it really the case that the Imperial Rescript on Education is rooted in Japanese tradition?

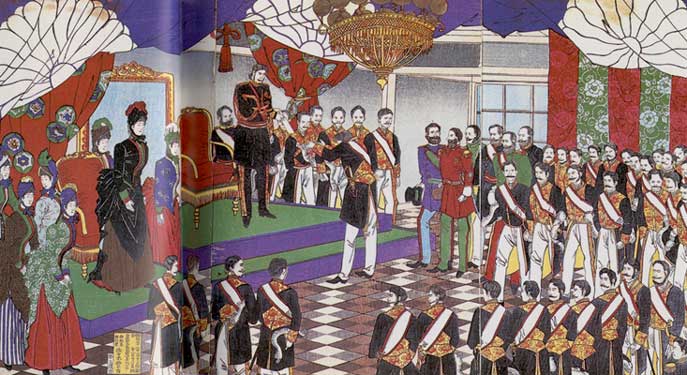

Presenting the Meiji Constitution

The Imperial Rescript spells out various virtues, the cardinal one being expressed in the words, “Should emergency arise, offer yourselves courageously to the State, and thus guard and maintain the prosperity of Our Imperial Throne coeval with heaven and earth.” In other words, in time of war defend the country by giving your life for it.

To me as one of the last of the wartime generation, during the Pacific War that was called the “Greater East Asian War” the words “die for the emperor” seemed to resound throughout heaven and earth. In conformity with these words, many of my friends fought bravely and died in a war that was recklessly started and which no effort was made to stop even when defeat was staring us in the face. It was my fortune to survive this war, but from the bottom of my heart I hated it for driving some three million Japanese to such meaningless death.

After the war, the reason I switched from specializing in Western philosophy to Japanese religion and culture because I felt it impossible to produce an original philosophy while ignoring Japanese culture and thought, and also because I became keenly aware of the magnificence of Japanese culture, despite my hatred for the Japan that had caused this war. What later became known as “Umehara Japanology” was born of this combination of love and hate.

I take the view that the Imperial Rescript on Education stemmed from the early Meiji policies of “Get rid of the Buddhas” (Haibutsu-Kishaku) and “Separate the Kami, or Japanese deities, from the Buddhas” (Shinbutsu Bunri). From the time of Prince Shotoku [574-622], Buddhism was Japan’s official religion, but it soon merged with Shinto, the religion of the Japanese people from Jomon [neolithic] times. The merger of Shinto and Buddhism, started by Gyoki [668-749] and Saicho [767-822], and perfected with Kukai’s [774-835] esoteric Buddhism (Shingon-Mikkyo), lasted as Japan’s tradition until the end of Edo.

However, as the Meiji government fell under the ideological sway of narrow-minded “National Learning” (Kokugaku) scholars, they set about implementing policies designed to separate the Kami and the Buddha and to demolish Buddhism. In the end they killed off not only the Buddha but the Kami too, and in the space created by the absence of both Buddha and Kami they set the emperor as the new divinity. This process may be described as the creation of “New Shinto” [or State Shinto]. This New Shinto contributed to making Japan a power comparable to the Western states, by internally consolidating the political control of the Satsuma-Choshu-led government that replaced the Tokugawa shogunate and by externally focusing the power of the whole nation under the emperor.

The philosopher, Watsuji Tetsuro [1889-1960], set out in his war-time book “The Philosophy and Tradition of the Philosophy of Revering the Emperor” to prove that the ideology of seeing the Emperor as a god was a Japanese tradition, but he was not successful. The idea of the Emperor as a deity can be seen in the Kojiki and Manyoshu [8th century] and in texts such as the Jinno Shotoki [14th century], but it was not until after the middle of the Edo period (circa mid-17th century) that such ideas became popular and they were then utilized in the [19th century] process of overthrowing the Tokugawa shogunate.

Under such religion, Japan developed as a modern state, became a great power, plunged into the “fifteen year war”, and met the miserable fate of defeat. The English philosopher, Bertrand Russell, raised the question of how Japan, where no one was allowed to question the divinity of the head of state, could have become a modern state.

After the war, under the orders of General MacArthur New Shinto was rejected, and an edict declaring the humanity of the Showa emperor [Hirohito] was issued. It seems bizarre that, in the 20th century where scientific thinking dominated the world, the Emperor should have had to issue an edict declaring himself human. I met the Showa Emperor several times and could not help seeing him as a genial old man who loved the study of biology. How painful it must have been for such a person to play the role of a god. Mishima Yukio totally rejected the announcement of the emperor’s humanity and wrote in his novel Voices of the Heroic Spirits (Eireitachi no koe) that the emperor should have insisted on his divinity. I believe, however, that the real modern Japan started from this declaration of the emperor’s humanity.

The fact of the present emperor alluding to Takano-no-Niikasa, the mother of Emperor Kanmu and the descendant of King Bunei of Paekche, by saying that he “feels an affinity for Korea” and telling the zealous promoters of the movement to raise the Hinomaru (national flag) and sing the Kimigayo (anthem) that “it is best for them not to be imposed by force” – something that even a liberal academic could not easily say – leads me to think that the members of the imperial family are very liberal, and probably are themselves inclined to oppose the kind of Emperor system spelled out in the Imperial Rescript on Education.

Let me repeat. The Imperial Rescript on Education is not something rooted in Japanese tradition. Is it not rather the case that revival of the Imperial Rescript on Education would allow politicians who have neither knowledge nor virtue, and who have no love whatever for traditional culture but care only for their self-interest, to make the people do their will by representing it as the order of the emperor? It seems to me that the only way to make the Japanese people truly moral is to have them come to a deep understanding of the Japanese tradition of reverence for both Kami and Buddha.

Umehara Takeshi, long the director of the International Research Center for Japanese Culture (Nichibunken) in Kyoto, is the author of numerous works on Japanese and Asian philosophy, archeology and history. For other essays by Umehara, see Japan Focus No. 135 and 167.

This article appeared in the Asahi Shimbun May 17, 2005, evening edition. It was translated for Japan Focus by Yusei Ota and Gavan McCormack. Yusei Ota is a student and Gavan McCormack a visiting professor at International Christian University in Tokyo. Gavan McCormack is also a coordinator of Japan Focus. Posted at Japan Focus July 12, 2005.