Takeshi MATSUDA

By the end of World War II, the U.S. government had recognized how important a cultural dimension of foreign policy was to accomplishing its broad national objectives. International relations in the twentieth century was no longer just a matter of relations between governments; it was a matter of people-to-people contact as well. President Harry Truman clearly sensed the advent of a new age. On August 31, 1945, he proclaimed that “the nature of present-day foreign relations makes it essential for the United States to maintain information activities abroad as an integral part of the conduct of our foreign affairs.”[1] In September 1945, Assistant Secretary of State William Benton articulately expressed similar beliefs about the importance of an international information program: “The development of modern means of communication has brought the peoples of the world into direct contact with each other. Friendship between the leaders and the diplomats of the world is important, but it is not enough. The people themselves must strive to understand each other. We must strive to interpret ourselves abroad through a program of education and of cultural exchange.”[2]

Five years later, in 1950, Truman pointed out that the U.S. overseas information and education program was achieving results: “The task is not separate and distinct from other elements of our foreign policy. It is a necessary part of all we are doing to build a peaceful world. It is as important as armed strength or economic aid.” A State Department cultural affairs officer echoed Truman’s words in later years in describing the character of American cultural diplomacy; “Together [programs of cultural relations, educational development, and information dissemination] comprise one leg of a three-legged stool of U.S. diplomatic relations–along with the political and economics.”[3] Apparently, this State Department officer wished to draw public attention to the integration of three dimensions of American foreign policy–security, economics, and culture–into a single framework.

On April 12, 1950, about two months before the onset of the Korean War, Truman announced that the United States would undertake a multimillion-dollar “Campaign of Truth” to combat worldwide communist propaganda and to give other peoples “a full and fair picture of American life and of the aims and policies of the United States Government.”[4] The U.S. cultural offensive was part of the U.S. efforts to achieve a “preponderance of power” over the Soviet Union and its communist allies.. This effort included carrying out psychological warfare and programs of gradual cultural infiltration throughout the world, including in key countries such as Japan, France, and Italy. From a historical perspective, however, the Campaign of Truth was neither new nor the first U.S. government attempt to meet the nation’s foreign policy objectives by cultural means. It was in fact part of a revival and an extension of the activities of the Office of War Information (OWI).

OWI was abolished in August 1945, and responsibility for administering the overseas information program in peacetime was transferred to the new Office of International Information and Cultural Affairs in the State Department (later designated the Office of Information and Education Exchange). But the Office of Information and Education Exchange was short-lived. In its stead, two separate offices, the Office of International Information (OII) and the Office of Educational Exchange (OEX), were established in 1948 in the State Department. OII and OEX, known jointly as the U.S. Information and Education Service, or USIE, took charge of U.S. cultural foreign policy as of 1948. USIE called itself “the third arm of foreign policy” or “a basic arm of United States foreign policy.”[5]

The U.S. Congress responded patriotically to Truman’s request for bolstering the Campaign of Truth. Actually, the anticommunist Campaign of Truth was in line with National Security Council paper 13/2 (NSC 13/2, October 1948), which called for a hard-line cold war policy toward Japan in particular and which brought about the “reverse course” in the U.S. occupation of Japan. The Campaign of Truth was supported by the significant increases in congressional appropriations that followed the outbreak of the Korean War. Indeed, Congress almost quadrupled the budget earmarked for international information activities in 1951: from $32.7 million to $121.2 million. In addition to the regular appropriation of $32.7 million for 1951, the first supplemental appropriation provided $79 million for the Campaign of Truth and the third supplemental appropriation for 1951 added another $9.5 million. Thus the Truman administration received $88.5 million over the regular appropriation of $32.7 million, including substantial increases for radio operations, press and publications, motion pictures, exchange of persons, and various other cultural activities. In the first half of 1951, for example, daily language programming by the Voice of America (VOA) increased more than 50 percent, from thirty hours and twenty-five minutes to forty-eight hours and twenty minutes. With the addition of daily broadcasts in nineteen new languages, forty-eight language programs were being produced by June 30, 1951.[6] As a result, the United States was able to maintain increasingly more powerful information and cultural programs abroad.

The Campaign of Truth in Japan

The Campaign of Truth in Japan had a specific objective in fighting the cold war: to create “a politically stable, economically viable nation that is capable of defense against internal subversion and external aggression and allied to the United States and the free world.”[7] American leaders such as Truman, Dulles, and Rockefeller had recognized the increasing importance of a cultural dimension in U.S.-Japan relations, particularly in the post-treaty period. With U.S.-Japan relations specifically in mind, a public affairs officer in the U.S. embassy in Tokyo explained the important role that the embassy was to play in 1951: “With the current stress on the power features of the Peace Treaty and on the bilateral Security Treaty, the broadly cultural aspects of the future Embassy operation take an added importance as a balance to the whole.”[8] Thus the cultural dimension of postwar U.S.-Japan relations was truly one of the three main pillars (security, economics, and culture) supporting the U.S.-Japan bilateral relationship, especially from the early 1950s on.

In aggressively pursuing its anticommunist Campaign of Truth against the background of the growing influence of communism in Japan, public affairs officers in the U.S. embassy in Tokyo implemented psychological programs aimed at combating “the misconceptions widely circulated by Soviet propaganda agencies.”[9] Saxton Bradford understood that Japanese intellectuals could not be weaned away from their firmly held misconceptions about the United States by merely listing American virtues, disparaging the Soviet Union, and sounding a call to arms against communism. The U.S. embassy in Tokyo made special efforts to reach the leaders of the press and radio who were in a position to influence the thinking of large and varied segments of the Japanese population. It considered youth leaders, labor leaders, farmer leaders, women, and government officials to be the most important target groups, in that order of priority[10]

The overseas information program was implemented not only through the media–radio, press, publications, motion pictures–but also through the libraries and information centers operating abroad and exchange programs. For example, twenty-three information centers were in place in Japan in 1951, and at least fifty American professional librarians worked in the U.S.-run information libraries scattered throughout Japan.[11] The information centers, which used an educational and cultural approach to which the Japanese proved to be particularly susceptible, were the focal point of U.S. information activities. The centers contained a theater, a large space for exhibits, and spacious meeting rooms, as well as library facilities. USIE officers, aware of the importance of reaching opinion makers in Japan, maintained contact not only with a great many city people but also with a substantial portion of the Japanese population living outside of the major cities. To interest Japanese intellectuals in the American information centers, USIE recommended that they send a particular professor or intellectual a postcard explaining the services of the center or inviting attention to a certain book or books. Apparently a frequent user of the information center, Saito Makoto, a professor at Tokyo University, was greatly appreciative of the books available there: “Such a center does more for Japan than an Army battalion and costs much less.”[12] As a result of efforts like this, the centers won public support from literate and attentive Japanese people.

The “Spiritual Vacuum” and Japan’s Vulnerability to Communism

What were the social conditions in Japan as USIE began to carry out its information and educational programs? For one thing, the entire population was in a “spiritual vacuum” and thus extremely vulnerable to communist influence. The confusion resulted largely from the war itself. The military defeat had left the Japanese in a state of kyodatsu (exhaustion and despair); they were profoundly confused, indecisive, and lacking direction in their basic philosophy of life. The Japanese emperor had been regarded as a living god, who had supreme responsibility for protecting Japan, the divine country, from destruction and desolation. But the indiscriminate bombings, defeat, and subsequent military occupation abundantly demonstrated the fallibility of the supposedly infallible deities, including the emperor. Consequently, the religious orientation of the people had been thrown into turmoil. The abolition of emperor worship with one stroke of the pen under the directive of the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers dealt the Japanese an additional crushing blow, leaving American diplomats in the U.S. embassy in Tokyo unable to identify an existing religion that might fill the “spiritual and ideological vacuum” of the Japanese.[13] Both they and the Japanese government felt they confronted two problems that had to be addressed immediately: how to fill the spiritual vacuum of the people and how to cope with Japan’s vulnerability to communism.

Not only high-ranking Japanese government officials but also conservative leaders in business and industry were seriously concerned about the social implications of Japan’s “spiritual vacuum.” Among others, Mitsui Takakimi, a former member of the Mitsui zaibatsu family, disclosed his apprehension when he met with John Rockefeller in New York City in June 1951, telling him that there was “a real need for something to fill this void.” In his opinion, the Japanese people could not comprehend the full meaning of democracy.[14] Rockefeller recognized the seriousness of the spiritual crisis facing the people of Japan, and he shared Mitsui’s concern. He knew that in Western democracies an underlying Christian faith gave people spiritual sustenance and fighting vigor in times of adversity, but the Japanese had lost this great source from which to draw a fighting incentive.[15] Rockefeller therefore suggested that the Japanese gain knowledge about the thinking and ways of the free world. He told Mitsui confidently, “Such knowledge and understanding will do much toward eliminating the intellectual and spiritual vacuum which exists as a result of Japan’s defeat and recent period of relative isolation from the rest of the world.”[16]

State Department officers such as John Emmerson were as concerned about Japan’s spiritual vacuum as Rockefeller and Mitsui. Emmerson reminded Dean Rusk that “the ‘spiritual vacuum’ in Japan, mentioned by a number of Japanese coming to this country, is a very real and serious problem.” He pointed out that if the United States wanted “to try to avoid Japan’s swing either to the Far Right or to the Far Left, some further thought and planning would seem to be required.”[17] John Foster Dulles, America’s indefatigable cold warrior, also grasped the seriousness of Japan’s vulnerability to communist propaganda. He was deeply troubled by the “mysterious Japanese elasticity”–that is, he wondered why the Japanese had become suddenly and apparently democratic in such a short period of time, even though previously they had been thoroughly controlled by military leaders. But Dulles found the answer: the Japanese were “fundamentally non-religious.” Dulles suspected that they did not “possess the requisite religious and spiritual qualities to withstand Communism over the long haul.” And yet he was pleased to know that many Japanese were anticommunist, even though he recognized that the primary reason they hated communism was not because they were opposed to it, but because communist ideology was connected so intimately with the Soviet Union. He also suspected that the Japanese never found the idea of subordination to a strong ruler an odd one, because they had no firm belief in the essential worth of the individual. In short, Dulles found it hard to believe that the Japanese would remain noncommunist for long.[18] Longtime Japan resident Otis Cary had another take on the situation; he reflected that “possibly [the] Occupation had in reality opened doors of [the] country to Communism by breaking down old patterns of people and not putting anything that people could grasp in its place.” In that way, the United States “may have done more harm than good.”[19]

Marxism also had been very popular in Japan’s universities before the Pacific War of 1941-1945. After the founding of Tokyo Imperial University in 1877, all things German enjoyed wide popularity among its students and scholars. For example, until the end of the war German history classes constituted 80 percent of the Western history classes offered. Moreover, all Japanese universities had unmistakable influences of German logic, German philosophy, and German ideas about law and the state. As a result, most Japanese scholars were under the influence of German Marxists. Marxism, especially theoretical Marxism, a stepchild of Hegelian dialectics, received considerable attention from Japanese intellectuals, in part because of this exclusive orientation of Japan’s prewar institutions of higher learning, in both form and substance, toward German academic thinking.

Political scientist Maruyama Masao has argued that after World War II Japanese intellectuals remained as much under the strong influence of Marxism and communism as they had been during the interwar years.[20] Immediately after the war, Marxists and communists enjoyed almost a monopoly of popularity and credibility among Japanese, because many had steadfastly maintained their ideological stance even while in prison during the wartime years. In Japanese academia as well, a scholarly debate over Japan’s modern capitalism raged, including the issue of dependence versus independence in Japan’s relationship with the United States.[21]

American leaders were so paranoid and obsessed with the fear of communism that they tended to exaggerate the degree of the communist threat–and they tended to view Japan through the lens of such paranoia and fear. Ethnocentrism and sometimes racism also added to the difficulty in seeing the country objectively. Consequently, many utterances of the Americans revealed their frustration and anxiety as well as their condescension and contempt toward the Japanese. Americans were not the only ones with contemptuous views of Japanese intellectuals, Jakev Levi, a correspondent of Borba, the organ of the Yugoslavian Communist Party, stopped over in Tokyo in January 1952 on his way home from covering the Korean War. After discussing a wide range of issues concerning world affairs with members of the Japanese Committee for Cultural Freedom (Nihon Bunka Jiyu Iinkai), the Yugoslavian journalist derided Japanese intellectuals for being naïve and out of touch with reality, wishy-washy about defending their own country, possessive of “no critical faculties,” and ignorant of the aggressive, imperialistic, and non-Socialist nature of the Soviet Union. Apparently, Saxton Bradford found much resonance with Levi’s characterization of Japanese intellectuals. He sent Levi’s story to the State Department, attached to his own critical commentary on Japanese intellectuals.[22] But how did the Japanese and Americans view each other’s people and cultures?

Japanese Views of America and American Culture

American diplomats in Tokyo assumed correctly that Japanese scholars had a low opinion of America, especially American culture. For one thing, Japanese scholars described America as more materialistic and less idealistic than other countries, and they found Americans to be loud, vulgar, and short on gentleness and sensitivity. In other words, Japanese professors portrayed Americans as people without much interest in cultural matters, despite all their material possessions. Japanese intellectuals also found marriage, family, and home in America to be bankrupt. In addition, they pointed out that the United States was home to racial prejudice and, in the South, the long-standing practice of racial segregation. Finally, Japanese intellectuals viewed America as a country that opted for expediency over principle and idealism. [23]

Most Japanese shared the scholars’ stereotypical images of America. They believed that American civilization lacked spiritual and cultural dimensions and that American culture was shallow. And they assumed that Americans tended to think only in material terms, because America was a materialistic nation without “soul.” They also thought that the average American was technically skillful but underdeveloped in cultural interests and intellectual capacity. As an American diplomat in Nagoya reported, “There does exist a genuine admiration for the American industrial and scientific advancements. But [there is] very little appreciation for our cultural or spiritual attainments.”[24] Most Japanese also perceived America to be a violent and immoral country, with gangsters going berserk in big cities such as Chicago and New York and Americans given to intoxication and wild sprees. Of course, these Japanese views of America and Americans did not necessarily represent the reality of modern America.

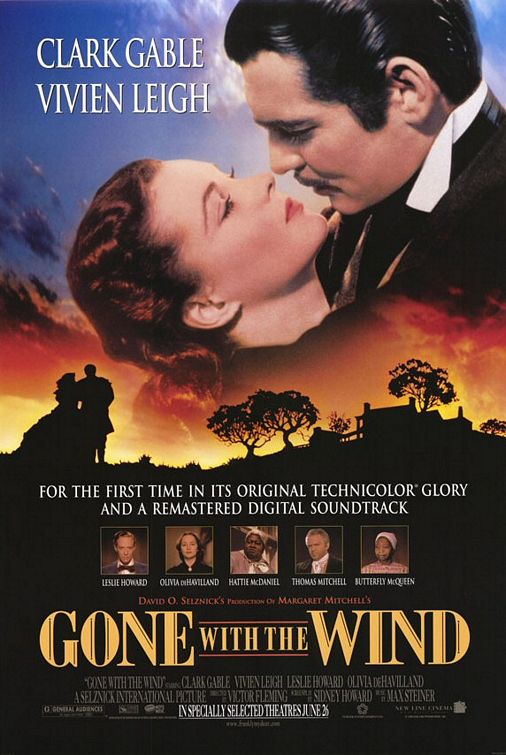

American motion pictures were partly responsible for the negative images that Japanese held of American culture. Japan had over two thousand commercial motion picture theaters. More than a third of the playing time in these theaters was given not to Japanese films but to pictures from abroad.] Indeed, American films had a tremendous influence in postwar Japan. For example, Gone with the Wind, a long-running American movie, opened on September 3, 1952, and turned out to be a great success. More often than not, however, moviegoers took away negative images of America from the films or documentaries that were made largely for amusement purposes. Indeed, Hollywood movies tended to subject Japanese viewers to exaggerated pictures of America. On the whole, then, the Japanese perceptions of American culture were less than flattering, if not entirely negative.[25]

Japanese intellectuals did not take American scholarship and culture very seriously until the end of World War II. The long association between Japanese intellectuals and their European counterparts made it easier for Japanese intellectuals to discuss European social concepts than American ones. For that reason, the Hepburn chair of American Constitution, History, and Diplomacy was not established at Tokyo Imperial University until 1918. It was the first American course offered in the history of Japanese university education.[26] Japanese scholars found the philosophy of American capitalism and individual responsibility quite difficult to understand, because American capitalism seemed to them to be something like self-interested materialism.

Japan and the Japanese in American Eyes

As described earlier, Americans and foreign visitors generally formed contemptuous assessments of Japan and the Japanese, but it appears that such assessments reflected their ignorance about the country and its people. Westerners had a tendency to misunderstand and form misconceptions about Japan and its people. Actually, they more often than not projected their preconceived ideas upon Japan and its people only to reconfirm their stereotypical image. Thus their impressionistic observations of Japan often turned out to be either a distorted view of Japan or an illusion.

And what exactly were the perceptions of Japan and the Japanese? Westerners generally lamented that Japanese had a distinct psychological disposition toward being led. Americans, in particular, were afraid that Japanese were easily moved by circumstances without logical consideration and public discussion–that is, they were prone to being confused by clever propaganda, being controlled by a few leaders, and accepting newly imported movements (such as religion-based democracy, cultural movements, peace movements, and spiritual movements) promptly and yet superficially, without understanding the true meaning of them. Americans thus had a cynical disdain for the intellectual capacity of the Japanese people.[27]

Obviously, the fear of communism reinforced such negative and effete images of Japan and its people, which necessarily reflected the Western ethnocentric and patronizing attitude toward them. Westerners seldom questioned their assumption that the Japanese were so childish and immature that they had to be taught the theory of democracy thoroughly and plainly. And yet Westerners truly believed that they were undertaking a supreme mission in which the Japanese had to be shown the true examples of advanced American, British, and Scandinavian democracy. After all, the best way to protect the Japanese from the communist threat was to explain clearly and accurately the strong points of democracy. At the same time, Westerners believed the Japanese had to be taught in the same fashion the essential spirit of Christianity, because Christianity should be the motivational power behind the anticommunist and democratic movements. Otherwise, the Japanese might begin to accept the idea that communism was not so bad after all.[28] Westerners understood that “many Japanese who are not Communists now could become Communists rather easily if they were convinced that the Communist Party was going to control Asia.”[29] This fear of communism was a powerful driving force behind the U.S. cultural offensive in Japan.

These assumptions epitomized the perceptions about Japanese intellectuals among U.S. Embassy personnel. Saxton Bradford and his colleagues at the U.S. embassy in Tokyo found certain characteristics of Japanese intellectuals quite annoying and a counterforce to the Campaign of Truth in Japan, particularly the distorted views of America and American culture that were generally shared by Japanese scholars. They were unable to stomach such views, they said, not so much because Japanese intellectuals’ opinions were based on an unfavorable interpretation of facts, but because their views were “based on a complete misapprehension of what America was like.”[Bradford profoundly regretted that university circles were infected with unfavorable stereotypes of American life, and that they were biased toward a Marxist orientation. He remarked that Japanese ignorance of America and American culture was “not that of a blank mind but rather that of a mind filled with [a] firmly held misconception about the United States.”[30] He also criticized university professors for helping to create anti-American feeling among Japanese.

Second, American public affairs officers such as Bradford and Niles W. Bond held the disdainful view that the Japanese did not have adequate political, religious, or individual experience to understand Anglo-Saxon concepts of human rights, democracy, freedom, and many others that reflected the idea of American democracy. They suspected, therefore, that the Japanese confused the substance and form of many occupation-sponsored reforms because of their lack of understanding of American ideas and thought. They suspected as well that much of what was said about democratic ideas and organizations was unintelligible and rang hollow to most Japanese, because few seemed to understand the philosophical bases on which U.S. institutions rested.[31]

Third, the American diplomats in Tokyo were disturbed by the presumed naiveté of Japanese intellectuals about the nature of world politics. Bradford was especially bothered by the fact that Japanese professors seemed to apply a double standard in judging U.S. and communist conduct, imagining an ideal Marxist society that did not actually exist in the Soviet Union and a society of predatory capitalism that did not actually exist in the United States. Bradford ascribed this unfortunate situation not only to the fact that a large portion of Japanese intellectuals did not have well-informed opinions of the United States, but also to the fact that they had no favorable views of U.S. foreign policy objectives.[32] Moreover, the American diplomats alleged that Japanese professors had practically no up-to-date knowledge of international affairs and that the Japanese were, on the whole, ignorant of the current world situation around them and the real nature of the Soviet state and Soviet foreign policy. Bradford was keenly aware that Japanese intellectuals preferred to steer a middle course and to take a neutral stance in the Cold War for fear that a commitment to either side might make Japan once again the scene of battle. But he argued that this was a dangerous illusion.[33]

Saxton Bradford and other American visitors to Japan also scornfully pointed out that two closely related traits characterized Japanese intellectuals: a disposition toward abstract theory and ivory tower thinking. American public affairs officers claimed that Japanese professors were too theoretical and not sufficiently empirical. According to them, Japanese scholars tended to elevate theory and the history of theory over analysis of what had actually happened. It was charged that Japanese leftist intellectuals were loath to listen to anyone who would not take a theoretical position, assuming that the theoretical and abstract represented the highest form of scholarship, while observational and statistical studies, particularly those related to the contemporary period, belonged to a lower order.[34]

A group of visiting professors from Stanford University also argued that these were characteristics of Japanese intellectuals. After participating in the first U.S.-Japan seminar, held in 1950, they reconfirmed their preconceived image of Japanese scholars based on their conversations with Japanese participants in the seminar. Indeed, the American professors were struck by the fact that Japanese scholars were so theoretical.[35] Theodore Cohen, the Labor Division chief of General Headquarters’ Economic and Scientific Section, regretted that the Japanese audience had not appreciated the lectures given by a professor from the Food Research Institute. The Japanese participants complained that the American lecturer “could not argue Marxist dialectic but had insisted on talking facts instead of theory.”[36]

American scholars, especially Council on Foreign Relations experts on Japan, held a similar view of their Japanese counterparts. Princeton University professor Frederick Dunn and others pointed out that Japanese elite intellectuals preferred theory to an actual description of the world in which they lived. In fact, far too many Japanese scholars seemed content to simply add annotations to those of other annotators, which resulted in a dearth of analytical studies.[37] The American professors from Stanford observed that because there was a wide gap between pure research or scholarship and “practical affairs,” Japanese intellectuals needed a great deal of mental adjustment before contemporary studies could become respectable and before there could be an easy relationship between scholars and men in public affairs.[38] As a remedial measure, they suggested that Japanese professors learn from their American counterparts an important lesson: theoretical considerations should be related to the facts.[39] And yet the harsh criticism leveled at Japanese leftist intellectuals about their overly theoretical or abstract thinking was based too much on exaggeration, and it did not necessarily hit the mark.

The second trait of Japanese intellectuals identified by Saxton Bradford was the long-standing tendency toward ivory tower thinking. Bradford did not hesitate to belittle the Japanese elite for being exceedingly withdrawn, theoretical, and of the ivory tower variety. The American diplomats like him felt that university professors were prone to becoming recluses and losing contact with broad new developments by carving out small, isolated spheres for research.[40] They charged Japanese scholars with remaining aloof from direct participation in politics and business affairs. Howard S. Ellis, Stanford professor of economics, confirmed his preconceived view that Japanese scholars had “a strong penchant toward ivory tower thinking as well as a traditionally imbedded disinclination of the academic community to concern itself intimately and genuinely with contemporary social and economic problems.” From his first-hand experience teaching the 1951 American Studies seminar, he acknowledged that the Japanese participants were “the cream of the crop from the numerous schools all over Japan” and that “their level of intellectual and professional sophistication is very high.” However, Ellis ended his commentary on a sharp note, saying that “their lack of acquaintance with America, particularly of those many subtle elements going into the American ‘way of life,’ is appalling.”[41]

In all fairness, ironically because SCAP/CI&E carefully and severely controlled expression of opinion on occupation matters, most Japanese scholars exercised self-censorship in the presence of the occupying power and kept their mouths shut altogether during the military occupation. In addition, the General Headquarters staff and American soldiers lived apart from the Japanese community for security and other reasons. Japanese intellectuals found it extremely difficult to express their views openly and freely and tended to be reticent in public discussions. Takagi Yasaka, a former student of renowned historian Frederick Jackson Turner and the pioneer of American Studies in Japan, described a situation in which “there were all too few opportunities for Japanese to discuss international problems freely with Americans or even with each other. It was difficult therefore to arrive at well informed opinions.”[42] Therefore, the Americans’ harsh criticism of Japanese intellectuals should be taken with a grain of salt.

To win the hearts and minds of the Japanese in fighting world communism, Bradford decided that the U.S. government must display more adequately and systematically the intellectual and cultural attainments of America in the mainstream of Greco-Roman traditions and the Judeo-Christian culture. He thus suggested that the United States use the strongest weapons in its cultural arsenal–books on history, economics, political science, psychology, anthropology, and sociology–in an attempt to compete with other Western books.[ He observed that in these realms of scholarship the United States was in the vanguard, and American writings on these subjects could prove that the Americans, too, were able to theorize–a point on which the Japanese needed to be assured.[43]

Once Bradford accepted this difficult task, he plunged into it as his self-imposed mission. He was determined to better acquaint Japanese academicians with the reality of the world, so they might be able to realize where the true interest of Japan lay. Perhaps because of his profound fear and obsession with the growing communist influence in Japan, Bradford insisted that “a calm analysis based on simple fact [would] be more effective than a diatribe or a monotonous diet of straight anti-communist propaganda.” He also took particular note of the Japanese admiration for American goods and techniques to tie in the Japanese economy and applied science with their American counterparts.[44]

The Cultural Cold War and Promoting Historical Studies in Japan

In the midst of this situation, how was the Campaign of Truth actually carried out in Japan? Public affairs officers at the U.S. embassy in Tokyo recognized that postwar Japan was in a state of flux–that is, it was a time of historical transformation when ideas and ideals played an important role in shaping people’s minds and perspectives and in conditioning the pattern of human behavior. Because all Japanese, not just Japan’s intellectuals, were determined to rebuild their nation from the ashes as quickly as possible, Americans believed that the study of history was enormously important; it would provide people with a sense of perspective without which the present would seem obscure and contemporary problems would look complex and confusing. Historians were in a position to throw light on the present through a deeper understanding of the past and of the historical process from past to present.

The U.S. embassy officers in Tokyo thus focused their utmost attention on Japanese historians, who, they recognized, had a great influence on Japanese readers. This effort was conducted against the backdrop of Japan’s role as a battleground of the cultural cold war in East Asia and the U.S. government’s deep commitment to fighting communism throughout the world. Actually, the Rockefeller Foundation also played a large part in fighting communism–it contributed significant funds to the humanities, of which history was an important part. For example, from 1950 to 1960 the total grants in the humanities given by the Rockefeller Foundation reportedly amounted to $37.6 million, of which about $7 million (roughly 19 percent) was earmarked for work in history.[45] Apparently, Japanese historians attracted the attention of American philanthropic foundations, including the Rockefeller Foundation.

At the time it was about to regain independence, Japan had over two hundred universities, thousands of historians, and immense library and archival resources. But American philanthropic foundations such as the Rockefeller and Ford Foundations saw Japanese historical studies rife with the growing Marxist influence over the interpretation and the writing of history.

As in other areas of intellectual inquiry, the Marxist interpretation of history, which already had been influential in the prewar years, became dominant during the American occupation of Japan after the nationalist contenders were eliminated. Japanese liberal scholars and commentators were unhappy about the situation. In his letter to the Rockefeller Foundation’s Charles Fahs, Matsumoto Shigeharu lamented, “I am convinced that Japanese historiography is presently in a state of mess. And something must be done about it before it is too late.” He called for a more humanistic approach to the study of history and a non-Marxist approach to social sciences as well.[46] Sakanishi Shiho, a woman writer, ascribed the dominance of Marxist dialectical materialism in Japan’s scholarship to SCAP’s suppression of the more traditional historical teaching and its early encouragement of the Japanese left wing.[47] Paul Langer, who was in Japan studying the history of communism among Japanese students in his capacity as a Social Science Research Council researcher, agreed with these Japanese liberals. In an interview with Rockefeller, Langer remarked that “two fields of study which seem to be particularly in hands of men committed to Communist line of thinking are Russian Studies and Japanese History. Most of Japanese history studied in schools of Japan has Marxist slant. What would be most constructive would be to offer [the] brightest young men in these two fields [a] chance to study in U.S., England or even elsewhere.”[48]

The key historical period in modern Japanese history was the last half of the nineteenth century when the foundations of modern Japan were laid. The Meiji Restoration that overthrew the feudalistic Tokugawa regime, in particular, was the focal point of historical inquiry for many Japanese scholars oriented toward Marxism. According to Fahs, “The dogmatic Marxist interpretation of that particular period provided the basis for the Communist doctrine with regard to where Japan was situated today and what the country should do tomorrow.” Fahs felt an urgent need to do something to counter the growing influence of Marxism in Japan. He and other officers of the Rockefeller Foundation thought it important “to support the few Japanese historians who were able and courageous enough to resist this prevailing dogmatism through new and more thorough studies of Japan’s modern history.”[49]

Another aspect of historical research that non-Marxist liberal scholars and the Rockefeller Foundation found peculiarly Japanese was the relative scarcity of good biography, especially political biography. Fahs identified the writings of good political biography with the development of a healthy democracy: “Biographic emphasis on the role of individuals rather than abstract social forces is healthy.”[50] To redress the messy situation, Matsumoto recommended that biographical approaches to the study of political science and history be considered, because “Marxist analysis of politics and history reduces all great leaders to pawns of inevitable historical forces.”[51] Accordingly, the officers of the Rockefeller Foundation looked for opportunities to encourage the writing of biography in Japan. Indeed, they succeeded in discovering Japanese candidates to suit their need. As a result, one grant-in-aid was awarded in 1955 to Tokyo University professor of political history Oka Yoshitake for his proposed work on the political biography of Yamagata Aritomo. And two grants-in-aid were made in 1958–1960 to Kyoto University professor Kosaka Masaaki for his proposed projects in biography and nondoctrinaire interpretations of modern Japanese history.[52] Both Japanese scholars received fellowships from the Rockefeller Foundation on the merit of their research proposals and on the integrity of their scholarship. But it seems undeniable that the decisions of the Rockefeller Foundation were made primarily with a view toward coping with too much Marxist influence in Japan.

Similarly. Professor Sakata Yoshio, who specialized in the modernization of Japan, was selected a Rockefeller Foundation fellow in 1956. Sakata of the Institute of Humanistic Sciences at Kyoto University was trying to revise Japanese intellectual history, believing strongly that doing so was “particularly important because of the distortions introduced by the Marxist school dominant among Japanese historians.”[53] He was nominated for the honor by John W. Hall, a professor of Japanese history at the University of Michigan.[54] Fahs recognized that “Our help will enable them (non-Marxist historians) to move further ahead into the Meiji period.”[ He remarked in later years that the goal of combating the Marxist influence in Japan was an important consideration in the final selection in 1956 of grantees of a coveted Rockefeller Foundation fellowship, even though the Rockefeller Foundation declared in its mission statement that it was nonpolitical and nongovernmental.[55] This episode reveals that, notwithstanding its proclaimed principles, the Rockefeller Foundation was not necessarily above dodging its ideological neutrality at the height of the cultural cold war.

Promoting Area Studies in America and Abroad

The Rockefeller Foundation was equally anxious to promote area studies at home and abroad. At first, the concept of area studies was developed as a means of coordinating the many different disciplines in the social sciences and humanities with the goal of understanding a single culture or an area. According to historian Benjamin I. Schwartz, “An area is, so to speak, a cross-disciplinary unit of collective experience within which one can discern complex interactions among economic, social, political, religious, and other spheres of life.”[56] Area studies presumably provided the best approach at the academic level to achieving a mutual understanding of the civilization of two or more countries and the spirit underlying their cultures. Scholars utilized the comparative method in integrated area studies, continually drawing contrasts between the culture under study and their own cultures. It was presumed that the development of an intercultural viewpoint contributed to objectivity in either direction. Thus the interdisciplinary or cross-disciplinary approach of research and teaching became a popular way in which to break down the unnecessary barriers between the “disciplines.” In summary, then, area studies can be defined as an “integrated study combining the method of social sciences and the subject matters of the humanities for working out the total culture or civilization of a region.”[57]

In area studies, the subject matter is usually a single culture or an area. At the risk of oversimplification, two different approaches have been proposed and practiced in area studies: the problem-oriented approach and the humanistic approach. In the problem-oriented approach, the problem may have to do with the ideas of modernization, developing economies, or democratization. This approach tends to center on the social sciences in which political science plays a particularly important part. In the humanistic approach, history and literature play a central role, with a special emphasis on the historical development of a given culture or area. This approach, because it seeks to reconstruct the total image of the culture or civilization of a given area, requires a great variety of knowledge about the area in question. Although the best approach to pursuing area studies is still being debated, whichever approach an area studies expert may choose, he or she is expected to synthesize a body of knowledge into a holistic picture of a country or area and its culture.[58]

Area studies emerged in the United States during World War II as part of the war effort. The field had grown out of the military language schools established to train young men and women in the languages of the enemy. In 1941 when the United States was at war, William J. Donovan, director of Office of Strategic Services (OSS), explained the rationale for employing the nation’s best expertise in OSS, saying that it was to “collect and analyze all information and data which may bear upon national security.”[59] Thus area studies developed to meet the need to gather and provide information about enemies. The purpose of training young people was to have them serve as interrogators of the Japanese–and later the Koreans, Chinese, and Vietnamese. The Research and Analysis branch was widely thought to be the most successful program in the OSS.[60] Anthropologist Cora DuBois believed that the collaborative work undertaken by the OSS during the war was the prelude to a new era of reformist thinking on an interdisciplinary basis: “The wall separating the social sciences are crumbling with increasing rapidity. People are beginning to think, as well as feel, about the kind of world in which they wish to live.”[61] Many scholars so trained played an important role in government activities during World War II. Two decades later, in 1964, McGeorge Bundy, dean of arts and sciences at Harvard University, recalled that “it was a curious fact of academic history that the first great center of area studies [was] in the Office of Strategic Services.”[62]

By the end of World War II, the United States had made considerable progress in area studies. In the immediate post-World War II era, area specialists were much sought after, because American political and economic expansion around the world required informed, specialized knowledge of specific regions. Concurrently, the relatively new field of area studies was urgently promoted to meet U.S. security needs as the cold war loomed large on the horizon.

As the wartime experience demonstrated, area studies were so essential to the operation of foreign policy that the federal government and private foundations such as Rockefeller, Ford, and Carnegie were willing to provide area studies specialists with generous funds to obtain the authoritative knowledge available to them. Although the U.S. government took over the responsibility for funding area studies programs with passage of the National Education Defense Act in 1958, private foundations continued to pour money into established area studies programs in the United States.[63] As a result, large infusions of federal and private money contributed to the creation of many research and teaching programs in university area studies centers that focused on different regions of the world.[64]

Meanwhile, the American government and private foundations such as Rockefeller funded the expansion of American Studies abroad and, as a result, contributed much to founding centers for American Studies in foreign countries, including Japan. The Rockefeller Foundation assisted Japanese scholars in developing American Studies in Japan with the support of the U.S. embassy as it went about conducting the Campaign of Truth in Tokyo. Ironically, however, American “soft power” diplomacy brought Japan the mixed results of solidification of the hierarchical order of Japan’s centralized university system and scholars’ abiding habit of dependency.

Takeshi Matsuda is a professor of American history at the Graduate School of International Public Policy, Osaka University. This essay is an adaptation of chapter 6 of his recent book, Soft Power and Its Perils: U.S. Cultural Policy in Early Postwar Japan and Permanent Dependency, Washington DC and Stanford, CA: Woodrow Wilson Center Press and Stanford University Press, 2007.

Notes

1. Quoted in Walter L. Hixson, Parting the Curtain: Propaganda, Culture, and the Cold War, 1945–1961 (London: Macmillan, 1997), 5.

2. William Benton, “Statement,” Department of State Bulletin, September 23, 1945, 430, as quoted in Howard R. Ludden, “The International Information Program of the United States: State Department Years, 1945–1953,” Ph.D. diss., Princeton University, Princeton, N.J., 1966, 44.

3. As quoted in Warren M. Robbins (USIA), “Toward an American Global Cultural-Educational-Informational Program in the Framework of the Present World Scene,” December 14, 1960, Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs, U.S. Department of State, Historical Collection, Special Collections Section, University of Arkansas Libraries, Fayetteville.

4. As quoted in Hixson, Parting the Curtain, 5. Also see Rosemary O’Neil, “A Brief History of Department of State Involvement in International Exchange,” fall 1972, Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs, U.S. Department of State, file 12, box 103, Historical Collection, Special Collections Section, University of Arkansas Libraries, Fayetteville.

5. Ludden, “International Information Program of the United States,” 91 and Niles W. Bond, USPOLAD, Tokyo, to U.S. Department of State, USIE Country Paper on Japan, August 16, 1951, 511.9421/8-1651, U.S. Department of State, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C. (hereafter NARA)..

6. Richard T. Arndt, “Beikoku no bunka koho gaiko–Kiwadoi baransu” [Cultural and informational diplomacy in the U.S.: The precarious balance], Kokusai Mondai 338 (May 1988): 46; Ludden, “International Information Program of the United States.’; U.S. Department of State, Secretary’s Seventh Semiannual Report, 46, cited in Ludden, “International Information Program of the United States,” 157.; Hixson, Parting the Curtain, 16; Dubro and Matsui, “Hajimete veru wo nugu amerika tainichi senno kosaku no zenbo.”; U.S. Department of State, Secretary’s Seventh Semiannual Report, Table 1, 5, as cited in Ludden, “International Information Program of the United States,” 162.

7. Robert S. Schwantes, Japanese and Americans: A Century of Cultural Relations (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1955), 313–314.

8. Saxton Bradford, USPOLAD, Tokyo to the Department of State, Desp. No. 370, September 7, 1951, 511.94/9-751, U.S. Department of State, NARA.

9. NSC 125/2, “United States Objectives and Courses of Action with Respect to Japan,” August 7, 1952, Papers Relating to Foreign Relations of the United States 1952–1954, vol. 14, China and Japan, Part 2 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1985), 1306; Confidential memorandum, Notes on USIE Japan, March 3, 1951, U.S. State Department, 511.9421/3-351, NARA.

10. Information in this section is from Saxton Bradford, AMEMBASSY, Tokyo, to U.S. Department of State, “Attitudes of Japanese Intellectuals towards the United States,” June 4, 1952, 511.94/6-452, U.S. Department of State, NARA.; Earl R. Linch, AMCONSULATE, Nagoya, to AMEMBASSY, Tokyo, “Semi-annual Evaluation Report,” December 18, 1952, 511.94/12-852, U.S. Department of State, NARA.; Confidential memorandum, Notes on USIE Japan.

11. This information was provided by Prof. Kon Madoko with the cooperation of Ms. Bungo Reiko. An American library operated abroad under the jurisdiction of the State Department was called an American information library, whereas a library run under the jurisdiction of the U.S. Army in occupied countries such as Germany, Austria, Japan, and Korea was called an information center. In Germany, however, the American information center had been called Amerika Haus since October 1947. As many as twenty-seven such centers were operating in Germany in 1951. Kon Madoko, “Amerika no joho koryu to toshokan” [Interchange of information on America and library], Kiyo Shakaigakka (Chuo University) 4 (June 1994): 38. See also Barnes and Morgan, Foreign Service of the United States, 288. Similar functions for the occupied areas of Germany, Austria, Japan, and Korea were performed in coordination with the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Occupied Areas. Ludden, “International Information Program of the United States,” 96.

12. American Embassy, Tokyo, to U.S. Department of State, Memorandum of conversation between Professor SaitÅ of Tokyo University and Cultural Attaché Margaret H. Williams, May 5, 1953, 511.94/5-1153, U.S. Department of State, NARA.

13. Tokyo 1020 to U.S. Department of State, February 2, 1951, 794.00/2-251, U.S. Department of State, NARA; Saxton Bradford, AMEMBASSY, Tokyo, to U.S. Department of State, “IIA: ICS: American Books in Japanese Translation, 1952,” April 1, 1953, 511.9421/4013, U.S. Department of State, NARA.

14. Entry of June 19, 1951, John D. Rockefeller 3rd Diaries, series 1-OMR files, record group (RG) 5 (John D. Rockefeller 3rd), Rockefeller Family Archives (hereafter Rockefeller Diaries), Rockefeller Archive Center, Tarrytown, N,Y. (hereafter RAC).

15. Tokyo 1020 to the Department of State, February 2, 1951.

16. Report to Ambassador John Foster Dulles, April 16, 1951, folder 446, box 49, series 1-OMR files, RG 5 (John D. Rockefeller 3rd), Rockefeller Family Archives, RAC.

17. John K. Emmerson to Dean Rusk, confidential office memorandum, May 18, 1951, 794.00/5-1851, U.S. Department of State, NARA. For more information on Emmerson’s thoughts, see John K. Emmerson, The Japanese Dilemma: Arms, Yen and Power (New York: Dunellen Publishing Co., 1971); and Emmerson, The Japanese Thread: A Life in the U.S. Foreign Service (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1978).

18. “Japanese Peace Treaty Problems, Sixth Meeting, May 25, 1951,” Council on Foreign Relations Study Group Report, Manuscript Division, Council on Foreign Relations, New York.

19. Entry of Otis Cary, undated, Rockefeller Diaries.

20. Maruyama Masao, “Kindai Nihon no chishikijin” [Intellectuals of modern Japan], in Koei no ichi kara [From the position of the rearguard] (Tokyo: Mirai Sha, 1982), 71–133.

21. Takauchi Toshikazu, Gendai Nihon shihonshugi ronso [A debate over modern Japanese capitalism] (Tokyo: San-ichi ShobÅ, 1973); Kojima, Nihon shihonshugi ronsoshi.

22. Present at the meeting were ÅŒhira Zengo, professor of international law, Hitotsubashi University; Amamiya Yozo, chief of the Science Department, Yomiuri Press; Naoi Takeo, a New Leader correspondent; Hazama Shinjiro, an independent socialist; Fukuzawa IchirÅ, an author and critic; Tsushima Tadayuki, a painter and author of a book on Soviet economics; Okura Asahi, an executive secretary of Japanese Committee for Cultural Freedom; Arahata Kanson, a socialist leader and former member of the Diet; and Kohori Junji, an independent socialist. Yomiuri Shimbun, January 16, 1952; Saxton Bradford, USPOLAD, Tokyo, to U.S. Department of State, January 18, 1952, 511.94/1-1852, U.S. Department of State, NARA.

23. Niles W. Bond, USPOLAD, Tokyo, to U.S. Department of State, USIE Country Paper on Japan, August 16, 1951, 511.9421/8-1651, U.S. Department of State, NARA; Bradford, AMEMBASSY, Tokyo, to U.S. Department of State, “Attitudes of Japanese Intellectuals towards the United States.”

24. Saxton Bradford, AMEMBASSY, Tokyo, to U.S. Department of State, “Psychological Factors in Japan,” February 28, 1952, 511.94/2-2852, U.S. Department of State, NARA; . Robbins (USIA), “Toward an American Global Cultural-Educational-Informational Program in the Framework of the Present World Scene.”; Linch, AMCONSULATE, Nagoya, to AMEMBASSY, Tokyo, “Semi-annual Evaluation Report.”

25. Confidential–Security Information. USIE Country Plan–Japan, Priority III, December 4, 1951, 511.94/12-451, U.S. Department of State, NARA; Civil Information and Education Section, General Headquarters, Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers, Mission and Accomplishments of the Occupation in the Civil Information and Education Fields, January 1, 1950, folder 444, box 49, series 1-OMR files, RG 5 (John D. Rockefeller 3rd), Rockefeller Family Archives, RAC, 10; “Japan Between East and West, Fourth Meeting, May 21, 1956”; Council on Foreign Relations Study Group on American Cultural Relations with Japan, “The Exchange of Cultural Materials,” Working Paper No. 5, prepared by Robert S. Schwantes, April 22, 1953, folder 42 , box 6, collection III 2Q, RAC.; Sato Tadao, “Wareware ni totte amerika towa nanika” [What does America mean to us?] Shiso no kagaku 68 (November 1967): 4; Linch, AMCONSULATE, Nagoya, to AMEMBASSY, Tokyo, “Semi-annual Evaluation Report.”; . Bradford, AMEMBASSY, Tokyo, to U.S. Department of State, “Attitudes of Japanese Intellectuals towards the United States”; Arthur Thompson, “The Development of American Studies in Japan,” American Studies 5 (July 1960): 2.

26. See the entry “The Hepburn Chair” in Nichibei bunka kÅryÅ« jiten [A dictionary of Japan-U.S. cultural interchange], ed. Kamei Shunsuke (Tokyo: Nan-undÅ, 1988), 222–223; Fukuda Sadayoshi, “Hanbei shiso” [Anti-American thought], Bungei ShunjÅ« (September 1953):

.

27. Memorandum from Round Table Conference on Christian Culture and Peace, submitted to John Foster Dulles, April 19, 1951.

28. Ibid.

29. “American Cultural Relations with Japan, Sixth Meeting, June 3, 1953,” Council on Foreign Relations Study Group Report, folder 42, box 6, collection III 2Q, Rockefeller Foundation Archives, RAC.

30. Bradford, AMEMBASSY, Tokyo, to U.S. Department of State, “Attitudes of Japanese Intellectuals towards the United States.”

31. Tokyo 1275 to U.S. Department of State, March 15, 1951, 794.00/3-1551, U.S. Department of State, NARA.

32. Saxton Bradford to Niles W. Bond, Top Secret Memorandum on Draft Psychological Strategy Plan for the Pro-U.S. Orientation of Japan, July 28, 1952, 511.94/7-2852, U.S. Department of State, NARA. Tsurumi Shunsuke, “Nihon chishikijin no Amerika zÅ” [Japanese intellectuals’ images of America], ChÅ«Å KÅron (July 1956): 170–178.

33. Robert D. Murphy to Secretary of State, confidential security information, September 5, 1952, 511.94/9-552, U.S. Department of State, NARA.

34. Bradford to Bond, Top Secret Memorandum on Draft Psychological Strategy Plan.; Interview: entry of Matsumoto Shigeharu, November 4, 1954, folder 868, box 100, series 200, RG 1.2, Rockefeller Foundation Archives, RAC.

35. “Seminars in American Studies in Japan, 1950, Report of the Stanford Professors: Joseph S. Davis, Claude A. Buss, John D. Goheen, George H. Knoles, and James T. Watkins,” folder 5, box 1, series 205, RG 1.2, Rockefeller Foundation Archives, RAC (hereafter “Report of the Stanford Professors”).

36. Entry of March 2, 1951, Charles B. Fahs Diaries, series 12.1 diaries, Rockefeller Foundation Archives, RAC (hereafter Fahs Diaries).

37. “American Cultural Relations with Japan, Sixth Meeting, June 3, 1953,” Council on Foreign Relations Study Group Report, folder 42, box 6, collection III 2Q, Rockefeller Foundation Archives, RAC.

38 “Report of the Stanford Professors.”

39. Howard S. Ellis, Department of Economics, Stanford University, to Joseph H. Willits, director for the Social Sciences, Rockefeller Foundation, September 2, 1951, folder 6, box 12, series 205, RG 1.2, Rockefeller Foundation Archives, RAC.

40. Bradford, AMEMBASSY, Tokyo, to U.S. Department of States, “Attitudes of Japanese Intellectuals towards the United States.”; Thompson, “Development of American Studies in Japan,” 2.

41. Ellis to Willits, September 2, 1951.

42. Entry of May 7, 1950, Fahs Diaries.

43. Bond, USPOLAD, Tokyo, to U.S. Department of State, USIE Country Paper on Japan.; Bradford, AMEMBASSY, Tokyo, to U.S. Department of State, “IIA: ICS: American Books in Japanese Translation, 1952.” ;

44. Bradford, AMEMBASSY, Tokyo, to U.S. Department of States, “Attitudes of Japanese Intellectuals towards the United States.”

45. John W. Dower, “E.H. Norman, Japan and the Uses of History,” in Origins of the Modern Japanese State: Selected Writings of E.H. Norman (New York: Random House, 1975), 1-6.

46. Matsumoto Shigeharu to Charles B. Fahs, August 26, 1954, folder 12, box 2, series 609, RG 1.2, Rockefeller Foundation Archives, RAC.

47. Entry of April 7, 1952, Fahs Diaries. Careful readers may recognize that these cutting remarks on Japanese historiography by Japanese liberals such as Matsumoto and Sakanishi set the stage for the Showashi ronso (Showa history debate) in the 1950s. Showashi, a short history of ShÅwa Japan, was written in 1955 by three scholars of Japanese modern history: Toyama Shigeki, Imai Seiichi, and Fujiwara Akira. An article written by Kamei Katsuichiro, a literary critic, triggered the famous debate over the writing of the modern history of Japan. This concise history of the ShÅwa period, 1926–1988, captivated many historians, political scientists, philosophers, and critics, no matter their ideological persuasion, from 1955 and beyond.

48. Entry of Paul Langer, undated, Rockefeller Diaries.

49. “Humanities Program and Related Foundation Interests in History, 1950–1960,” prepared by Charles B. Fahs, November 16, 1960, pp. 6–7, file 18, box 3, series 911, RG3, Rockefeller Foundation Archives, RAC.

50. Ibid.

51. Matsumoto Shigeharu to Charles B. Fahs, August 10, 1954, folder 12, box 2, series 609, RG 1.2, Rockefeller Foundation Archives, RAC.

52. “Humanities Program and Related Foundation Interests in History, 1950–1960,” prepared by Charles B. Fahs.

53. Entry of April 26, 1956, Charles B. Fahs Diaries, Box 18, Record Group 12.1, Rockefeller Foundation Archives, Rockefeller Archive Center, Sleepy Hollow, N.Y

54. Tokyo University Center for American Studies (Tokyo Daigaku Amerika KenkyÅ« ShiryÅ SentÄ), ed., Ueno NaozÅ sensei ni kiku [Interview with Professor Ueno NaozÅ], vol. 10 of American Studies in Japan: Oral History Series (Tokyo: Tokyo University Center for American Studies, 1980), 28.

55. Dean Rusk (president), “Statement of the Rockefeller Foundation and the General Education Board to the Special Committee to Investigate Tax-Exempt Foundations,” Eighty-third Cong., 2nd sess., August 3, 1954, 1070.

56. Benjamin I. Schwartz, “Presidential Address: Area Studies as a Critical Discipline,” Journal of Asian Studies 60 (November 1980): 15.

57. William N. Fenton, Area Studies in American Universities (Washington, D.C.: American Council on Education, 1947), 82, 22.

58. Robert Hall, Area Studies: With Special Reference to Their Implications for Research in the Social Sciences (New York: Committee on World Area Research Program, Social Science Research Council, 1948); Miyoshi Masao and Harry D. Harootunian, eds., Learning Places: The Afterlives of Area Studies (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2002); “Discussion on ‘Chiiki kenkyu no arikata’” [“How area studies should be pursued”], American Review 6 (1972): 52–78; Tokyo University Center for American Studies, Matsumoto Shigeharu sensei ni kiku [Interview with Professor Matsumoto Shigeharu], vol. 9 of American Studies in Japan: Oral History Series. (Tokyo: Tokyo University Center for American Studies, 1980), 54–55.

59. Bruce Cumings, “Boundary Displacement: The State, the Foundations, Area Studies during and after the Cold War,” in Learning Places: The Afterlives of Area Studies, ed. Miyoshi Masao and Harry D. Harootunian, (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2002), 264.

60. Harry D. Harootunian, “Postcoloniality’s Unconscious/Area Studies’ Desire,” in Learning Places: The Afterlives of Area Studies, ed. Miyoshi Masao and Harry D. Harootunian, (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2002), 155.

61. Miyoshi and Harootunian, Learning Places, 268.

62. “The Program in the Humanities: A Statement by Fahs,” undated. folder 33, box 4, series 911, RG 3.1, Rockefeller Foundation Archives, RAC; Robert Gordon Sproul, president of University of California, to Chester J. Barnard, president of Rockefeller Foundation, July 12, 1950, folder 5, box 1, series 911, RG 3, Rockefeller Foundation Archives, RAC.; Cumings, “Boundary Displacement,” 261.

63. Harootunian, “Postcoloniality’s Unconscious/Area Studies’ Desire,” 156.

64. Stanley J. Heginbotham, “Shifting the Focus of International Programs,” Chronicle of Higher Education, October 19, 1994, A68.