Abstract: This article, intended as a companion to the recent documentary Us and Them: Korean Indie Rock in a K-Pop World co-produced by Stephen Epstein and Timothy Tangherlini, situates Korean indie and punk rock within a broader context in order to demonstrate how what may seem a byway within Korean culture serves as a useful index of important recent societal transformations. As the nature of not only global media flows and musical circulation but Korean national identity and economic structures all undergo significant change, how should observers understand “Korean” “indie” music and its meanings as of 2015? How have the local punk and indie scenes developed in concert with, and in contrast to, K-pop?

Keywords: South Korea, popular music, indie music, punk, K-pop.

In recent years, South Korean popular music’s quest for a share of the global market has proceeded with striking speed and success: idol bands from mainstream K-Pop have now carved out a fan base around the world, and PSY’s “Gangnam Style” has become, for better or worse, the most striking viral video phenomenon that humankind has yet witnessed. As a result, K-Pop has attracted international attention, with frequent coverage in prominent media outlets, and several scholarly volumes on the topic in English released last year alone (see, e.g., Choi and Maliangkay 2014; Lie 2014; Marinescu 2014).

Less well-known is that for two decades South Korea has possessed a vibrant independent music scene that is likewise reacting to the rise of K-Pop and the nation’s ever increasing engagement with the world at large.1 New opportunities and challenges now regularly present themselves. DFSB Kollective, for example, is an export-focused music marketing and distribution agency run by Bernie Cho, a Korean-American based in Seoul. In 2015, for the fifth consecutive year, Cho and his staff brought several indie groups to Austin’s renowned South by Southwest (SXSW) music festival to perform on a branded stage, titled SeoulSonic. Since 2014, they have also helped organize the “K-Pop Night Out,” which unites mainstream and independent artists. The event, one of the best attended international showcases at SXSW, is funded by KOCCA, the Korea Creative Content Agency, a government organization located under the auspices of the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism.

Conversely, in Mullae, a neighborhood with some of the lowest rents in Seoul, a new incarnation of the iconic punk venue Skunk Hell reopened in 2015 after a several year hiatus, fleeing its previous homes in Hongdae, the district that has long served as the center of the indie scene. Not only have leases in Hongdae become quite pricey, the district has also become too commercial and corporate for the liking of Won Jong Hee (Wŏn Chŏng-hŭi), the club proprietor (Twitch 2015). As the leader of RUX, Korea’s top street punk band, Won had once reworked Cock Sparrer’s Oi! classic “England Belongs to Me” for a version in which he sang, with conviction, “Hongdae Belongs to Me.” But perhaps Hongdae no longer belongs to RUX in a gentrifying K-Pop world. Amidst growing opportunities, the local punk scene also faces displacement and loss of identity.

Last year Tim Tangherlini and I completed a documentary entitled Us and Them: Korean Indie Rock in a K-Pop World (trailer here), which updates our 2002 co-production Our Nation: A Korean Punk Rock Community. In the second film we interview bands and individuals active in Korea’s indie scene to illuminate the complex and often contradictory developments currently shaping non-mainstream music there. In this article, intended as a companion to the documentary, I hope to situate Korean indie and punk rock within a broader context and to demonstrate how what may seem a byway within Korean culture serves as a useful index of important recent societal transformations. As the nature of not only global media flows and musical circulation but Korean national identity and economic structures all undergo significant change, how should observers understand “Korean” “indie” music and its meanings as of 2015? How have the local punk and indie scenes developed in concert with, and in contrast to, K-Pop? Much commentary on K-Pop treats it as an example of the decentering of the world’s popular culture industries away from traditional national powerhouses to alternate sites of production. What can be learned from the similar movement of subcultural, niche genres from a once peripheral country back to the global center, as seen in the growing awareness of a variety of Korea-based musical artists in the US, Europe and elsewhere?

Into a K-Pop World

The origins of this article in fact go back over a quarter of a century to when I spent a year studying at Yonsei University, a generally wonderful experience that ultimately led me to shift my academic focus to Korea. One aspect I found less than wonderful, however, was the music then heard ambiently in Seoul. In the late 1980s, long before the term K-Pop was coined, Korean popular music was rife with anodyne but often overwrought concoctions and Western soft rock was ubiquitous. In grad school I’d been playing bass in bands from the punk spectrum, and I experienced music in Korea as a mild form of aural torture. One day I heard “Rainy Days and Mondays” by The Carpenters in three different locations, and I began to wish for the power to make speakers combust at will. Unfortunately, I never mastered that skill, but it was a satisfying fantasy.

Nonetheless, during the 1990s, something I did find remarkable occurred in the landscape of Korean popular music, as it experienced almost seismic change (see e.g. Howard 2006). Seo Taiji and The Boys, a massively successful and critically respected idol group introduced rap (and, with less lasting influence, metal) into the biggest pop tracks of the day and set a template for the Korean music industry that has held sway since. Homegrown artists came to exert increasing dominance over the local soundscape, but at the same time, more alternative musical forms from overseas were gaining a foothold in Korea.

In 1998 as I headed to Seoul for sabbatical research, a fellow Koreanist who knew my musical tastes urged me to visit an underground club named Drug in Hongdae, which had been developing a reputation for its artsy, non-mainstream subcultures. From the moment I walked through the club’s door and heard the band playing, I knew that I’d found my spiritual home in Korea, and I became a regular during my stay. In addition to enjoying the music and the warm sense of camaraderie with band members and fans, I was also fascinated: what had allowed a punk scene to develop in Seoul in the 1990s when the possibility seemed so remote in 1989?

That curiosity led me to produce articles and a documentary exploring the emergence of punk rock in Korea in detail. As I have discussed elsewhere (Epstein 2000), the demise of military dictatorship in Korea and the ongoing processes of democratization in the 1990s spurred a cultural flowering in various spheres, most notably film. Local music also received a major infusion of energy with the opening of numerous live clubs, long suppressed because of their potential as sites of subversive activity. The interests of youth shifted away from political protest, and the rapid growth of Korea’s economy allowed a substantial increase in disposable income. The relaxation of stringent passport requirements meant that far more young Koreans traveled overseas, often bringing back new types of music to share with friends. Consumer culture took root in a concerted way, but creative impulses were also channeled into social critique.

In retrospect, it has also become clear that during the 1990s, punk, hardcore and indie music scenes were developing across Asia. While non-mainstream rock subcultures had already arrived in Japan by the 1980s, in the following decade scenes took root in Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, Taiwan and China at roughly the same time. 2 Although each national incarnation exhibits unique characteristics, collectively they were responding to similar phenomena and share common features. Increasingly rapid globalization and the discourses surrounding it encouraged new forms of popular culture engagement around the region, both celebratory and resistant. The historical coincidence of the rise of grunge with Nirvana, followed by the punk revival in North America in the mid-1990s, when Green Day, The Offspring and Rancid found wide success, also played a pivotal role in the rise of underground scenes throughout Asia (cf. Baulch 2007; Wallach 2014). As the decade wore on, the increasing penetration of the internet and MP3 technology made the sharing of music and musical knowledge easier than ever before.

While South Korea has long held fine bands, as do neighbors around the region, indie rock from the country currently treads a different path from counterparts because of its relationship to a burgeoning national mainstream that has stepped into the global limelight. The “Korean Wave”, or Hallyu, first driven primarily by the success of Korean film and dramas a decade ago in East and Southeast Asia, has resurged with the global success of K-Pop. The more recent version has been termed “Hallyu 2.0” because of both its fresh growth and the role that Web 2.0 social media platforms have played in spreading Korean products internationally (Lee and Nornes 2014). Idol K-Pop has occasioned curiosity in Korean music more generally, and interest spiked with the 2012 release of “Gangnam Style,” whose quirkiness led many around the world to seek out less conventional forms of the nation’s contemporary music.

Since the inception of an indie and punk scene within South Korea, bands have regularly defined themselves in opposition to hegemonic culture, and K-Pop presents a ready target. Consider, for example, one indie aficionado’s indignant 250-song YouTube playlist “Korea is not just K-Pop!” disputing a widespread image of Korean music as little but manufactured boy bands and girl groups. As elsewhere, contrasts are drawn between the authenticity of indie bands and the lack thereof in groups under contract with large corporate entities. The online biography of the RockTigers, who feature in our documentary, proclaims that “The RockTigers play one and only one kind of music: rock ‘n’ roll. They offer a trend-kill to all that’s wrong with the Korean music industry.” Within the film, the members of Korea’s most successful indie band Crying Nut make a similar distinction between themselves and highly trained, cookie-cutter groups in mainstream K-Pop who have their music written for them, rather than creating it.

Nonetheless, the unexpected rise of K-Pop affords an undeniable publicity boost for Korean bands who might otherwise remain little heard internationally. The likeliest route for anyone to encounter the aforementioned YouTube playlist and its artists is via a targeted search for K-Pop; the “bait and switch” action serves as a mundane but useful example of how bands today can grow an audience by virtual (in two senses) accident. Ever more often, indie artists find themselves traveling in a common national orbit with mainstream acts. Given Crying Nut’s stature in Korea and the band’s prior international experience, it is perhaps unsurprising that they appeared during the “K-Pop Night Out” at SXSW with major stars such as HyunA, the main female performer in “Gangnam Style,” and Jay Park. (The show’s profile was raised by the attendance of Lady Gaga; an image of Crying Nut member Kim Insu wound up on grammy.com, sandwiched between Neil Young and 50 Cent.) But the stage was also shared by little-known screamo act Hollow Jan, who must have raised the eyebrows of those who expected glossier music that evening.

Recent years have seen curious examples of rapprochement, such as when pioneer punk band No Brain engaged in an energetic collaboration with idol group KARA on national television to cover the ‘80s Korean pop hit “Pinggŭl Pinggŭl” (“Round & Round”), a staple of nostalgic recreations of the period. Bands are hardly unaware of these incongruities: as Sung Kiwan (Sŏng Ki-wan), the leader of top indie group 3rd Line Butterfly, notes to our camera with cheerfully self-mocking bemusement, if K-Pop stars like Girls’ Generation can open the door for Korean indie bands to perform overseas, that is cause for celebration.

As of 2015, what I call “Special K,” a letter that acts as a national branding mechanism, has become omnipresent in Korea. One finds it most obviously in K-Pop, but it also appears in such coinages as K-drama, K-movies, K-food, K-fashion, K-cosmetics, K-beauty, K-culture, K-heritage and so on. SeoulSonic not only taps into a punning identification with the capital in its name but also stamps each annual overseas tour with a series title: e.g., “SeoulSonic 2K15.” The letter K of course stands here for “thousand”; more importantly, it seeks to exploit the magnetism of the Korea brand. DFSB Kollective’s name likewise calls implicit attention to “Special K,” a logical enough strategy, given its connection to the K-Pop industry. More problematically, however, “K-indie,” a term that irritates many tied to the scene, has been surfacing with frequency. Can what is independent partake in an official branding project? How independent is indie music if it is sponsored (and potentially co-opted) by government, anyway?

Korean “Indie” Rock

South Korea ranks among those nations that have most assiduously built their cultural industries. Several connected with the indie scene have developed pragmatic attitudes in part because as the scene grows older, those involved have aged with it. Over the course of the new millennium, neoliberal ideology emphasizing self-care has taken deep root within South Korea and affected how musicians approach their craft in their choices along a continuum of accommodation or resistance to the imposition of neoliberalism. Many retain their passion for making music, but an evolution has been evident in the scene’s character from a vibrant expression of those who are “letting the energy of youth blaze,” as the liner notes of the early Chosŏn Punk compilation put it, toward a more professional version, self-confident, self-conscious and savvy. In interviews, members of Crying Nut regularly note continued love of playing music some 20 years after formation, and an infectious enthusiasm remains palpable in stage performances. However, bands that have been part of the underground also acknowledge a longstanding conundrum over how to make a living from music and grow a fan base while avoiding accusations of selling out.

The need to strike an appropriate balance has an added urgency in Korea, which in 2006 became the first major music market in which digital sales outstripped purchases of CDs (Messerlin and Shin 2013). South Korea remains notorious for music piracy, and musicians suffer financially at the hands of aggregated subscription streaming services that return lower revenues than digital downloads but capture a larger market share than elsewhere. Mainstream K-Pop now earns significantly more from international than domestic sales and has thus developed export-oriented strategies. Domestically, groups derive more income from concerts, endorsements and appearances on entertainment programs than music sales, spurring a particular emphasis on visuals in the Korean music industry. Likewise, much of Crying Nut’s income now comes from playing corporate events. As Lee Sang-Hyuk, the band’s drummer, stated during a 2014 interview, “When we started, there was this weird pride about not appearing [on] television, not trying to promote. You were a traitor if you showed up on TV. Now it is just normal for bands to do whatever they can to promote themselves.”3

A thorny dilemma Tangherlini and I wrestled with in titling the documentary was how to designate the music we were covering. Although our first film interrogated the suitability of the always contested label “punk” among the Korean bands we covered, the term at least served as a useful starting point in interviews. Some bands in the second film, though, such as the rockabilly artists The RockTigers or the angular and dreamy 3rd Line Butterfly, fit poorly under a punk rubric. We flirted with the term “underground,” but that designation has also become ill-fitting. 3rd Line Butterfly’s music has been used for television dramas, and, as noted, Crying Nut have achieved mainstream acceptance: their biggest hit is a staple of Korean noraebang (karaoke clubs), and they have contributed anthems for Korea’s World Cup soccer campaigns.

Ultimately, we settled on “indie rock,” although “indie” is itself a disputed term that has become problematic in English usage. What once suggested a free-spirited approach and a non-mainstream musical style has lost force amidst the commodification of cool and a blurring of generic boundaries. Korea’s borrowing of “indie” has undergone similar metamorphosis. The term entered circulation in the 1990s to describe the scene developing in post-democratization Hongdae, with phrases such as indi munhwa (indie culture) becoming widespread (Song 2005) along with the rise of alternative events like fringe festivals. In relation to music, however, the oppositional force of indi in Korean has, as of 2015, dissipated even further than in English. In current local parlance its use often simply designates artists as yet unsigned by a major entertainment company (Shin 2011) rather than a DIY sensibility or an even nominally adventurous musical style.

Furthermore, internet sites have been influencing global understandings of indie music in Korea by seeking to brand such artists under a “K-Indie” rubric and wresting control away from more underground acts. Many songs that turn up on YouTube’s Mirrorball Music channel, the most wide-reaching international source of dissemination for Korean “indie” groups (“YouTube Premium Partner. Everything About Korean Indie Music”), contain the highly produced, Top 40-oriented material that US indie rock bands and Korea’s underground artists have tended to reject. The channel displays a graphic that reads “K Indie” in the bottom corner of its several hundred videos and offers differentiated playlists for rock, pop, folk, rap/hip-hop and even jazz, blues, and reggae, muddying any generic definition of Korean independent music.

Allkpop, an international K-Pop news blog with several million views a month, ran a 2014 article that provided a list of song recommendations and the accompanying teaser: “What better way to keep summer vibes alive than listening to soothing Korean indie music? The following artists fall under the indie genre because they make music that is independent of major entertainment labels or studios…They’re perfect reminders of summertime lightheartedness and lazy days spent outdoors with friends or lovers.”4 Many such bands choose cute, playful names like Neon Bunny, J Rabbit, and Lucite Tokki (t’okki means “rabbit” in Korean) and use airy acoustic instrumentation that makes the “twee” indie pop of 1980s Britain seem like death metal. Marketing this more immediately digestible branch of Korean indie to a global audience as representative carries the negative consequence of obscuring the history, range and general character of music that the underground has produced.

From Scene to Shining Scene

In many respects, Hongdae’s reputation as a hotbed of indie culture has transformed it into, if not entirely a victim of its own success, a gentrified version of itself, colonized by less challenging approaches to music that tend towards common denominators (Shin 2011). Circumscribed territory and modest admission fees had once allowed a critical mass and the emergence of coherent subcultures. The district’s rising popularity, however, has attracted a more mainstream audience. The number of clubs centered in what is now branded, with the blessings of the Seoul metropolitan marketing machinery, the “Hongdae Entertainment District” has expanded in recent years, but the general character has changed, with an emphasis away from live music to DJs, dancing and drinking. Rising rents have necessitated higher ticket prices and driven out some venues that were bolder in their bookings, such as Club Spot, which closed in 2014 because it could no longer make ends meet. Now, a night out to enjoy live music is an event, more suited to young professionals than the youth who contributed to the vitality of the early underground scene. Economics have altered the organic aspects of community formation that were once a hallmark of the scene, as the loss of critical mass also means that a regular can no longer turn up at a given venue and be assured of encountering friends.

The indie, punk, hardcore, electronica and underground hip-hop scenes are of course largely composed of artists less successful than Crying Nut. Many do maintain opposition to the creeping tentacles of commercialism, upholding a DIY ethos in the face of larger transformations. In our documentary Sung Kiwan remarks that he has felt troubled that Hongdae’s commodification degrades the indie culture he knew but then calls himself back to question whether that is too radical a standpoint. In a recent interview for the long-running fanzine bROKe, Won Jonghee spoke about Skunk Hell’s move to Mullae:

“So like the animal Skunk we have to run away again. We have our own weapons. Rather than killing you we can fart and run away. That’s a pretty cute thing to do. Fart and run away. If I don’t like you, I don’t have to take you, I can just fart and run away. That’s why we don’t want this to end up like the other Skunk Hells. We don’t want this venue to be crowded with Nikes and Starbucks and all that. We want this street to fill up with people like us.” (Twitch 2015: 7)

While Won proudly asserts outsider status, reveling in the weapons of the weak (yet strongly scented), others accept the changes more wistfully as they work to find new venues upon being muscled out of favored spaces in Hongdae to play or to congregate, such as the centrally located playground which once was a popular gathering spot for Korea’s punks.

Although the local scene may therefore have lost its centripetal force, the centrifugal energy transforming it in unanticipated ways provides the compensations of reaching new audiences. Awareness has grown that the scene’s reach no longer is restricted to a single neighborhood in a single city, or even a single nation. In standing at the vanguard of the digital revolution, Korean musicians have actively exploited the ready distribution of music videos via YouTube and the other social media that have made the nation a standard of “cool” to many around the world. Myspace, Spotify and Bandcamp and the like create opportunities to connect with fans elsewhere, and platforms such as Facebook allow direct contact with venues overseas to set up tours and find places to stay.

These tactics have, of course, become widespread among musicians globally. However, consciousness specifically of South Korea as a rapidly rising global center of pop culture, in combination with the nation’s status at the frontlines of the digital world, often create a qualitatively different experience for its bands. As we filmed, bands members, who had grown up when Korea’s self-image was vastly different and anything but cool, would refer with wonder to discovering overseas pockets of fandom of which they had had no inkling.

Indeed, perhaps the single greatest change from the first documentary is that when we shot footage in 1999, not long after the IMF Crisis, few groups expected ever to perform overseas. Just keeping a band together as members went off to fulfill their mandatory military service requirements was a substantial challenge. From the mid-2000s, however, energetic members of the scene began to organize joint festivals with counterparts in Japan (Epstein 2006; Epstein and Dunbar 2007), and as time has gone on, more and more bands now play outside of Korea. All five groups spotlighted in Us and Them (Crying Nut, 3rd Line Butterfly, The RockTigers, The Geeks and …Whatever That Means) played in the United States within a year of our filming. Tour destinations have expanded, and bands travel elsewhere in Asia and to Europe and North America ever more frequently.

Within just the last few years Korean shows have, in fact, become a staple of not only SXSW but other major international music festivals like Music Matters Live in Singapore and Canadian Music Week. Some tours even act as an unequivocal component of Korea’s cultural diplomacy with official sponsorship: in 2015 a K-Indie Rock Showcase was held at the Korean Cultural Centre UK. Although bands certainly welcome opportunities to play overseas, the role of top-down government and business interests injects a note of dissonance. The UK is home to perhaps the world’s most elitist musical press and fully developed subcultural scenes, and the Cultural Centre’s Showcase promotion sought to differentiate itself through snob appeal: “And before some of you moan and groan, it’s not Kpop. This time the KCC has prepared something for all you cool Indie and Rock fans!”

“Korean” Indie Rock

Ambiguity in the meaning and use of “indie” is perhaps to be expected, occurring as it does in scenes around the world. More interesting—and at times surprising, given the determined use of letter K branding—are the ways in which indie artists from Korea rework national identity, sometimes accentuating it, but also eliding it. Currently the most successful Korean indie band overseas is Jambinai; the band’s members were trained in traditional music at the Korean National University of the Arts and their music grafts instruments like the kŏmun’go and haegŭm to a post-rock framework as a specifically Korean point of distinction. Jambinai’s fusion approach to a genre known for its experimentation with rock textures and structures has wowed Western critics, such as a reviewer for The Guardian who found it “thrilling, unexpected, and perfectly controlled” (Denselow 2015). Earlier this month (November 2015), Jambinai signed with the prestigious British indie label Bella Union, founded by members of the Cocteau Twins, and join such renowned bands as Explosions in the Sky and The Flaming Lips on its roster.

Choosing a different method to communicate origin, the RockTigers label their music as “kimchibilly,” for which their online biography, cited above, offers a playful elaboration: “Spicing up the classic rockabilly sound, The RockTigers are giving you rockabilly that’s vintage and modern from Seoul: Kimchibilly. You haven’t tasted Seoul until you’ve had a taste of Kimchibilly.” This sly coinage strips the original genre of “rock” and leaves a portmanteau of “kimchi” and, ultimately, “hillbilly,” that combines South Korea and the American South (Kim-Russell 2011) at the same time as it trots out a familiar vision of Korea as a blend of the traditional and the modern (with the RockTigers’ own postmodern twist). The term, suggested by a Canadian fan, may well indigenize rockabilly, but it explicitly targets outsiders. The RockTigers’ promotion expects lack of familiarity with Korea and its capital and treats Korea’s most famous food item as an object of tongue-in-cheek otherness even as the band moved toward a quintessentially American form. Indeed, within Korea, The RockTigers established a particularly large following among the expatriate community, which made them among the first Korean indie bands to feature in mainstream Western media (Glionna 2010), and served as a boost in enabling them to tour overseas. What Jambinai and the Rock Tigers do share, however, is a desire to capitalize on the allure of hybridity as an export-oriented strategy and in this they resemble many Korean Wave products.

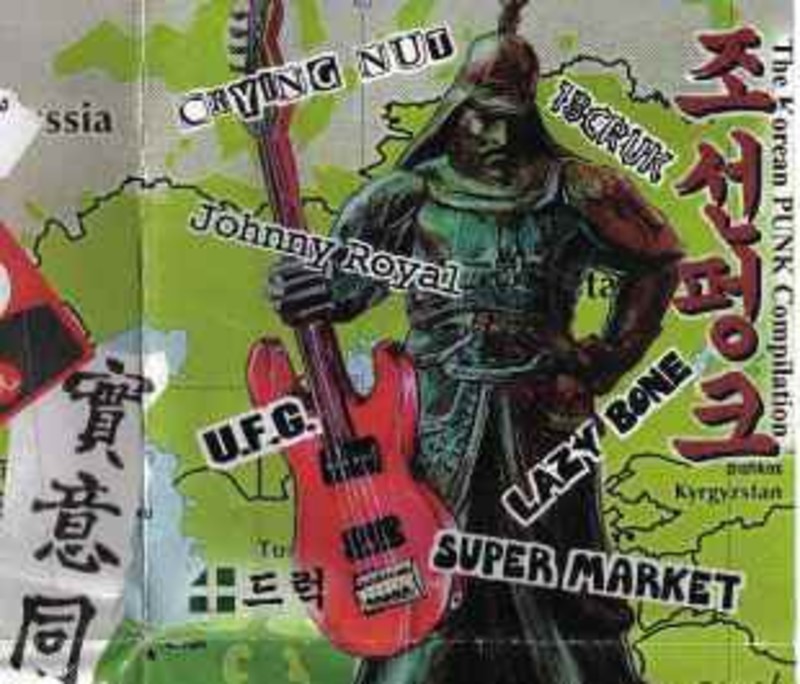

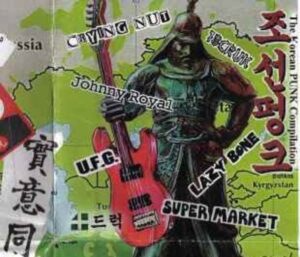

If one considers more specifically the punk and hardcore scenes over the last several years, however, a noteworthy trajectory appears in relation to national identity. In 1999, the first compilation CD to emerge from Drug carried the title Chosŏn Pŏngk’ŭ [Chosŏn Punk], whose nod to the Chosŏn dynasty (1392-1910) was intended to convey authentic yet ironic Koreanness in a very different way from “kimchibilly.” Even more striking than the title of the CD was the CD’s cover [Fig. 1], which depicts Admiral Yi Sun-shin, revered as a national savior for his role in warding off the Japanese invasions of the late sixteenth century, and thus a symbol of resistance to external threat, appearing as patron of a movement that eagerly appropriates a Western genre. Nevertheless, other than the subtitle “The Korean PUNK Compilation” and English-language band names, liner notes and song lyrics were in Korean. Punk may have arrived from beyond the nation’s borders, but localization was a crucial feature, and the target audience was entirely domestic.

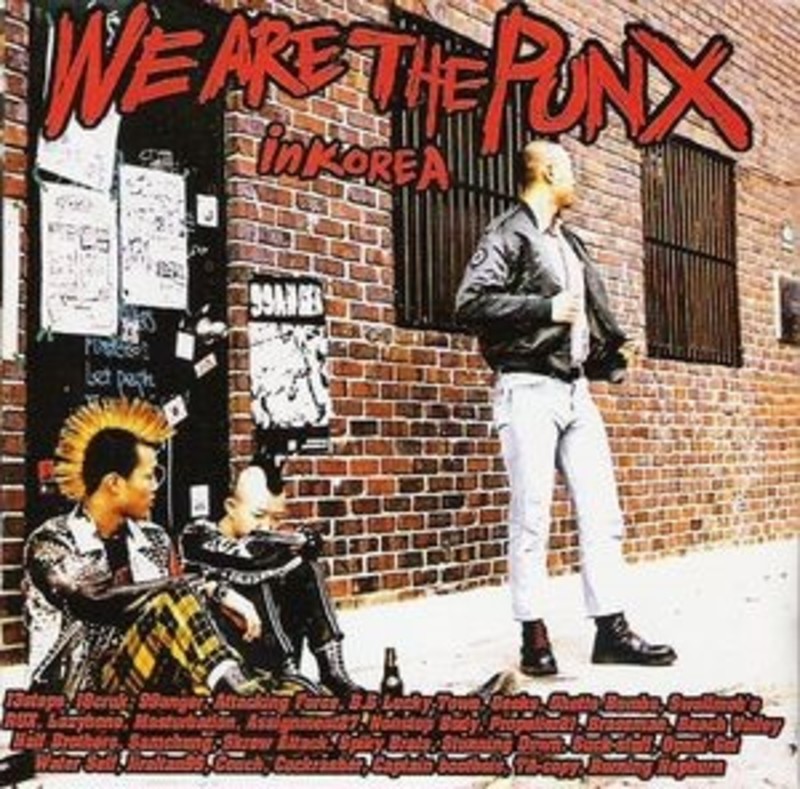

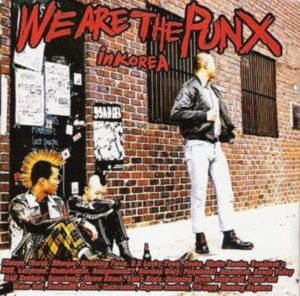

The title of the next scene compilation CD in 2003, We Are the Punx in Korea, however, already was shifting the focus significantly [Fig. 2]. “We Are the Punx” is written in much larger lettering than “in Korea” and the CDseeks to create allegiances with punks overseas and to set itself within a global context of a myriad local communities. Instead of featuring a national icon on the cover, the Korean identity of the figures present is subordinated to an international punk uniform of mohawks, combat boots, leather jackets, and Tartan pants. Accompanying liner notes from Won Jong Hee relate—in English—that,“the purpose of this compilation is … further to expand our Korean punk scene. We want to let more people from the world to know more about the local scene, produce more good bands and passionated minded [sic] punks.” Additional remarks from Joey, an American who later served as an occasional guitarist with RUX, also show that the primary source of identity was increasingly drawing on shared subculture and location, rather than national (or ethnic) belonging:

“I’m not the first Korean punk who isn’t Korean and I surely won’t be the last…It didn’t take me long to find the rest of punks. I can’t say the Korean punks because they are not all Korean. Which is why I like the title Jong Hee chose for the comp. It’s not ‘we are the Korean punx’.”

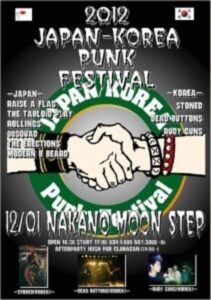

Shortly after We Are the Punx in Korea, the annual Korea-Japan Oi! Festivals began, leaving Korea intact as a reference point, but rejecting aggressive nationalism in favor of subcultural solidarity across the East Sea/Sea of Japan [fig. 3].5

As Seo Ki Seok (Sŏ Ki-sŏk), the leader of The Geeks, Korea’s most well-known hardcore band, states in an interview with the online magazine Vice: “At school, half the history book is dedicated to what Japan did to us…It’s done with a negativity that breeds passive hatred in everyone…We’re trying to readdress the balance in the hardcore scene by constantly having Japanese bands play too” (Hoban 2009).

The broadening of The Geeks’ horizons over the course of their career further suggests the arc of Korean indie music. They became among the first underground groups to play overseas, touring Southeast Asia and the US and developing a global reputation for their optimistic “youth crew” hardcore. As Seo states:

“We never set out to do anything other than play local shows. [But as] time passed we were setting new goals every year. We wanted to travel the world and we didn’t really care about how much money we were gonna lose…That’s what real hardcore is about–it’s about a global network. No matter what country you’re from it doesn’t really matter. We know for a fact we’re not in this alone, despite the fact the music we’re playing is far from commercial.” (Seo, quoted in Dunbar 2012)

Figure 3

Seo’s words are echoed in the title of their recent LP “Still Not in This Alone,” released on the American label Think Fast! Records, and his privileging of the global network of hardcore community over national identity also finds expression in an episode of Noisey’s recent documentary series Under the Influence, narrated by Tim Armstrong of Rancid: the Geeks feature prominently in an episode on the impact of the New York hardcore scene in which Seo speaks of the transformative effect that its bands had on his life.

Likewise choosing to downplay national origins in relation to the global circulation of indie music is Love X Stereo, whose electronic dance rock has been creating a buzz overseas. As their lead singer Annie Ko says, “Once a band makes it internationally, it doesn’t really matter where they’re from. We’d rather be known as a cool indie band than as a cool Korean indie band.”6 Though the Geeks and Love X Stereo differ markedly in sound, they display a similar attitude to their place as bands within a worldwide community of those bound by a shared love of music.

The Geeks and Love X Stereo are also similar in representing another crucial transformation in the Korean indie scene: Unlike K-Pop, which usually throws in mere smatterings of (often unidiomatic) English as a hooky seasoning for songs that are otherwise largely in Korean, almost all of the songs of both bands are in English; their well-educated lead singers have spent extensive periods abroad and are functionally bilingual. In the late 1990s Korean remained very much the default language of music and musicians of Hongdae, but our documentary captures the commonplace code-switching of today, with Koreans speaking in English, foreigners speaking in Korean, and individuals, both native Korean and not, moving comfortably back and forth between the two, sometimes within the span of a single utterance.

Us and Them

Over the last quarter of a century, the number of foreign residents in South Korea has increased dramatically from under 100,000 in 1990 to almost 1.75 million as of September 2015 (Kim 2015), now reaching about 3.4% of the population.7 While this figure may seem low to those from settler societies, it represents a striking change in South Korea. Once inward looking and ethnically homogenous, South Korea now officially proclaims itself a multicultural society. This demographic shift has had a marked impact on the indie scene itself, which thrives on participation by not only transnational Koreans and diaspora returnees but foreigners. Indeed, as a progressive, open and youthful set of subcultures, the indie music scene may serve as a bellwether for the direction of South Korean society in the years to come. The scene’s character, as discussed throughout this article, well exemplifies the work of Emma Campbell, who has recently argued for the development of a new type of nationalism among young South Koreans that turns away from a sense of national kinship based on shared ethnicity in favor of one based around a “globalised culturalelement that reflects shared cultural values including modernity, cosmopolitanism and status among the young” (Campbell 2015: 489).

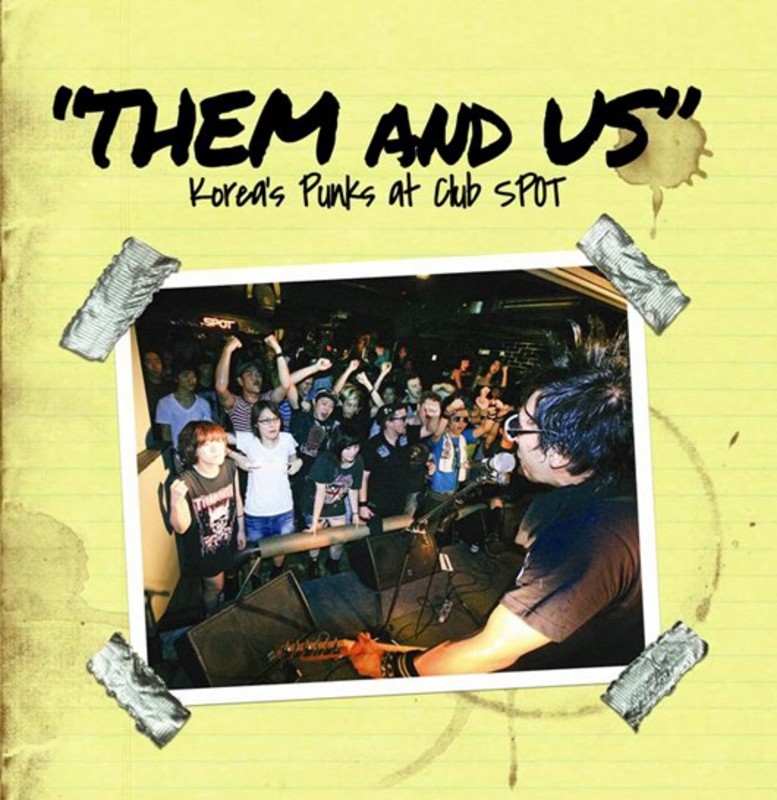

Our documentary filming in September 2011 coincided with the recording of the first punk scene compilation in several years, Them and Us: Korea’s Punks at Club Spot [Fig. 4].

Of course, the title of this CD necessitates probing who “them” and “us” are, and all the more since the initiative for the project came in large part from a Jeff Moses, a university English instructor from the US living in Seoul: the very production of the CD underscores how the Korean scene has been reaching out to the world and pulling outsiders back in return. The liner notes, composed by Moses, suggest multiple layers of inclusion:

“Them and Us” represents just a small part of the Korean punk and hardcore scene. Some of these bands helped [b]uild the scene way back in the early days, and some are the newest bands to join in. You’ll find men and women, punk and hardcore kids, Koreans and foreigners. In a time when K-Pop rules the airwaves, we all work together to promote our scene and expose people to the music we are passionate about. On this album, each band has paid tribute to a band that has inspired them and contributed one of their own original songs.”

Alliances of an “us” working together are thus seen as forming across generational, gender, subcultural and national lines, united to support the scene and build community in the face of K-Pop’s domination. The untidiness of setting boundaries of “us” and “them” is further mirrored in its implicit usage here in an oppositional sense (indie vs. K-pop) and a respectful one (bands reworking an influence).

One key area in which Korea’s indie bands differ from K-Pop, then, in any apparent move to a hybridized cultural odorlessness (Shim 2006; Shin 2009; Jung 2011: 3) is that they uphold a more intimate tie to geographic and temporal location. The Korean scene is now marked by the twin poles of an identity that is strongly local (cf. Shin 2011) and broadly international, with an increasingly ambivalent relationship to older conceptions of the national. Whereas idol K-Pop rarely features actual Korean rural landscapes or urban backgrounds in its music videos in its attempts to maintain a readily transferable global appeal, indie bands proclaim local allegiances frequently. Although one factor for the amount of homegrown color in indie music videos may be lower budgets, the use of Seoul as a regular backdrop also reflects a more vividly felt sense of place. Love X Stereo’s cosmopolitan ambitions are patent, but their most well-known song thus far is an ambivalent ode to “Soul City (Seoul City),” whose video depicts scenes of driving around the sprawling metropolis. As Ko states in an interview:

“[I]t’s not like we wanted to promote the city. It’s not like that at all. It’s our true feelings about the city. All the good and bad is in it. When I first heard Toby’s guitar riff, I instantly thought of Seoul. The way the song never seems to end, that was intentional too. We felt like Seoul never really ends, like a psychedelic song.”

Seoul has the fastest Internet services in the world, and there are so many great eateries, day or night. I love the Hangang river, I love the cycling, the Chimaek (chicken and beer shops). But I really don’t like all the negatives, the sense of failure in people’s daily lives, people working so hard for nothing, the drinking problems.”8

Bands composed of foreigners will often choose a name that explicitly reflects their current location within the capital, likewise drawing attention to their own border crossing (e.g. the Seoul City Suicides and Dongmyo Police Box).9

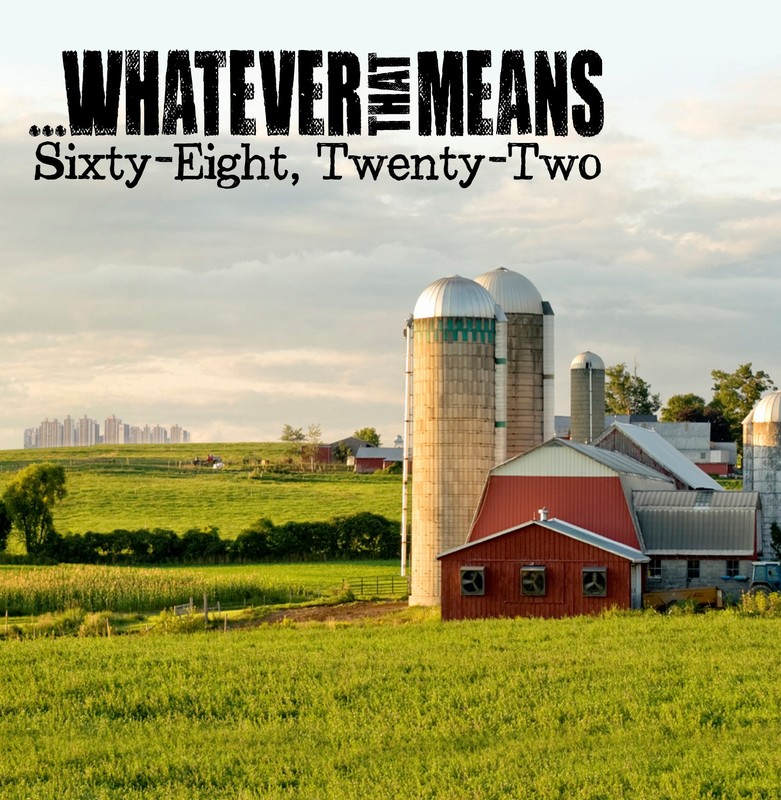

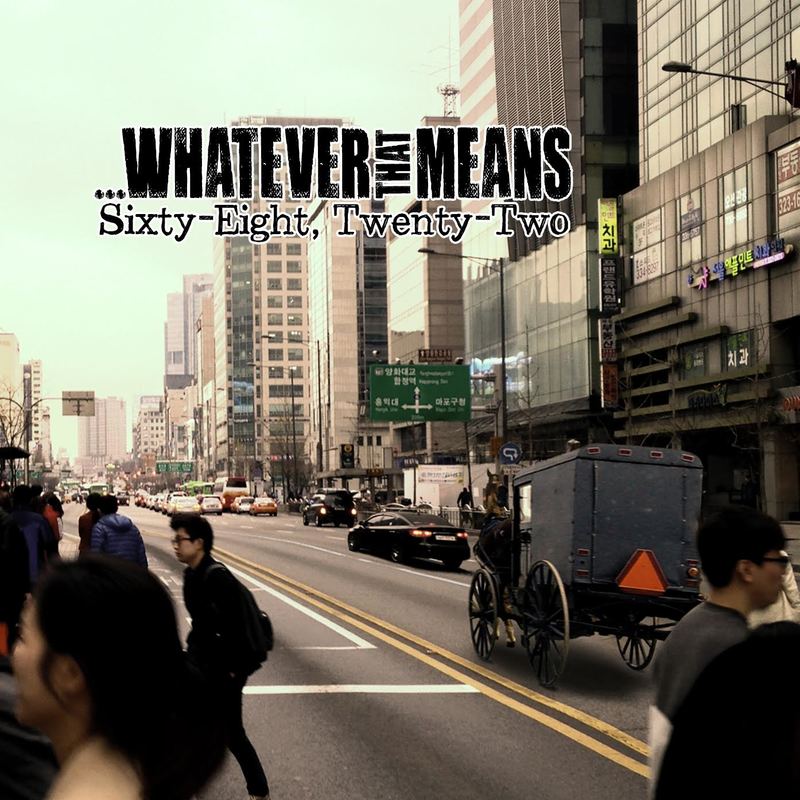

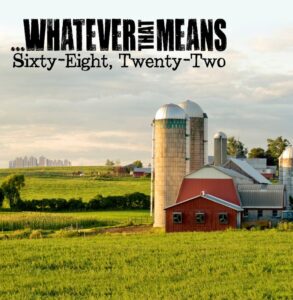

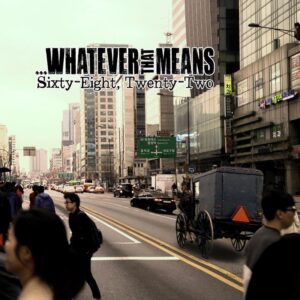

The most intriguing and explicit blending of the local and global occurs in the recent CD Sixty-Eight, Twenty-Two by …Whatever That Means, a melodic punk group, led by Jeff Moses, together with his spouse Trash Yang Moses, a stalwart of the scene who has played bass in several bands. The title track refers to the 6822 miles between Hongdae and Moses’ hometown in Pennsylvania. The CD art, some of which is included below [Figs. 4-8], has a series of ingeniously photoshopped images created by Trash that merge small-town Pennsylvania and urban Korea, such as the cover shot, which depicts a mid-Atlantic barn with a typically Korean apartment complex looming in the distance.

The accompanying music video for the title song, shot at the Moses’ apartment not far from Hongdae, with numerous well-known figures from the scene, both foreign and Korean, likewise emphasizes the collapsing of distance implied by the CD’s cover. The song’s lyrics and structure, which incorporates a verse/chorus trade off between Won Jong Hee of RUX and Moses, highlight the sense of international brotherhood and sisterhood in the Korean scene:

Come on in. Make yourself at home,

And maybe stay here for a while.

Don’t waste your time on the outside looking in.

Too many heads to count who have come and gone.

Never seen or heard again.

The rest of us are living with the lessons that we’ve learned.

Where you grow up and where you’re from,

They don’t always stay the same.

But when you find your heart somewhere,

You’ll know just what to say.

Conclusion

In our daily living in an era that on a regular basis is characterized as “rapidly globalizing,” the actual meaning of that clichéd, if legitimately applicable, phrase itself is rarely questioned at a deep level. The world was “rapidly globalizing” in the 1990s and it continues to “rapidly globalize” in 2015, but the contours of cultural globalization have evolved considerably over that period. The juxtaposition of our documentaries, filmed a dozen years apart, suggests substantial changes in the extent and nature of Korean society’s engagement with the rest of the world; the different place for the nation’s indie music locally and internationally also reflects differences in the nature of cultural globalization itself.

Taken together, the two films show how the phenomenon has developed from an indigenization of global musical forms to something far messier and more complex. The commonplace nature of mobility and border-crossing for immense swaths of the world’s population means that not only has consumption become internationalized but that people ever more frequently assume identities that pass beyond a single national state. Individuals are actively becoming producers of culture in multiple and overlapping contexts. Korean indie rock is increasingly embedded overseas and overseas indie rock musicians are increasingly embedded in Korea.

Indeed, the exponential growth in fluidity raises the question of whether, as globalization continues, national versions of “punk” or “indie” in Asia will largely be supplanted by labels that reference local scene. That is, it may not be the distant future before one speaks of Busan, Daegu or Mullae hardcore rather than Korean hardcore, much as the Los Angeles and New York hardcore scenes are referenced in preference to the category “American.” While national brand remains an obvious and almost unavoidable rubric, indie rock from South Korea effectively demonstrates that the national has undergone a very significant change even in the course of the last decade.10

In the light of my preceding discussion, I would also argue that South Korea’s music, at least, is moving well onward from the assertions made a decade ago about Western views of Chinese rock by de Kloet (2005: 324-325): “Whenever rock travels outside its perceived homeland, the West, it demands localization in order to retain its authenticity…Shown music videos of Chinese rock, Dutch students are generally dismissive; they consider Chinese rockers to be, at best, bleak, old-fashioned copies of the supposedly real rock from the West.” I am unable to assess whether youth in the Netherlands retain a similar attitude towards Chinese rock. Nonetheless, my conversations with university students from New Zealand and beyond, as well as the density and variety of comments in languages other than Korean on YouTube videos involving Korean indie bands strongly indicate that, as of 2015, many of the nation’s independent groups command respect as “authentic.” Global awareness of South Korea’s prowess as a producer of popular culture has risen, and interest has followed whether bands are engaging in palpable Korean localization à la Jambinai, or, as a result of talent, musicianship and songwriting skills, are placing an individual stamp on their music in the fashion of Love X Stereo, Hollow Jan, J Rabbit, RUX or the various bands that we treat in the documentary.

As a concluding note, I draw on the final words of Jeff Moses’ liner notes for Them and Us, and direct readers to the YouTube clips embedded throughout this article: “Enjoy the music. Support your own local scene, and if you’re ever in Korea come out to a show.”11

For information on purchasing Us and Them: Korean Indie Rock in a K-Pop World, please contact [email protected]

Recommended citation: Stephen Epstein, “Us and Them: Korean Indie Rock in a K-Pop World”, Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, Vol. 13, Issue 48, No. 1, November 30, 2015.

References

All websites accessed on November 15, 2015.

Baulch, Emma. 2007. Making Scenes: Punk, Reggae and Death Metal in 1990s Bali. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Campbell, Emma. 2015. “The End of Ethnic Nationalism? Changing Conceptions of National Identity and Belonging among Young South Koreans.” Nations and Nationalism 21.3: 483-502.

Choi, JungBong and Roald Maliangkay, eds. 2014. K-Pop: The International Rise of the Korean Music Industry. London and New York: Routledge.

de Kloet, Jeroen. 2005. “Sonic Sturdiness: The Globalization of ‘Chinese’ Rock and Pop.” Critical Studies in Media Communication 22: 4 pp. 321-338.

de Kloet, Jeroen. 2010. China with a Cut: Globalisation, Urban Youth and Popular Music. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Denselow, Robin. 2015. “Jambinai Review – Bringing Traditional Korean Music into the 21st Century.” The Guardian, Sept. 17.

Dunbar, Jon. 2012. “Korea’s Hardcore Scene.”

Epstein, Stephen. 2000. “Anarchy in the UK, Solidarity in the ROK: Punk Rock Comes to Korea.” Acta Koreana 3.1: 1-34.

Epstein, Stephen. 2001. “Nationalism and Globalization in Korean Underground Music: Our Nation, Volume One,” in Asian Nationalisms in the Age of Globalization, ed. by Roy Starrs. Curzon Press: Richmond, pp. 374-387.

Epstein, Stephen. 2006. “We Are the Punx in Korea!” in Korean Pop Music: Riding the Wave, ed. by Keith Howard. Global Oriental Press: Kent, pp. 190-207.

Epstein, Stephen and Jon Dunbar. 2007. “Skinheads of Korea, Tigers of the East,” in Cosmopatriots: On Distant Belongings and Close Encounters, Thamyris/Intersecting no. 16. ed. by Jeroen de Kloet & Edwin Jurriens. Rodopi: Haarlem, pp. 157-175.

Eum, Sung-won. 2015. “Number of Foreign Residents in Korea Triples Over Ten Years” The Hankyoreh, July 6.

Glionna, John M. 2010. “For RockTigers, It’s Rockabilly and a Lot of Seoul,” Los Angeles Times, May 13.

Hoban, Alex. 2009. “Korean Hardcore is Failing to Crush the Military.”

Howard, Keith. 2006. Korean Pop Music: Riding the Wave. Global Oriental: London.

Jung, Sun. 2011b.Korean Masculinities and Transcultural Consumption: Yonsama, Rain, Oldboy, K-Pop Idols.Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

Kim, Kang-han. 2015. “Woegugin chumini 5% nŏmnŭn ‘tamunhwa toshi’ chŏnguk 12 kot’ [‘Multicultural Cities’ with over 5% Foreign Residents Now Stand at Twelve].” Chosun Ilbo, August 28.

Kim-Russell, Sora. 2011. “Rockabilly, Born in the West, Travels East, Returns to the West.”

Lee, Sangjoon and Abé Mark Nornes. 2014. Hallyu 2.0: The Korean Wave in the Age of Social Media. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Lie, John. 2014. K-Pop: Popular Music, Cultural Amnesia, and Economic Innovation in South Korea. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Luvaas, Brent. 2013. “Exemplary Centers and Musical Elsewheres: On Authenticity and Autonomy in Indonesian Indie Music” Asian Music 44.2: 95-114.

Marinescu, Valentina, ed. (2014) The Global Impact of Korean Popular Culture: Hallyu Unbound. Lanham, ND: Lexington Books.

Matsue, Jennifer. 2008. Making Music in Japan’s Underground: The Tokyo Hardcore Scene. London and New York: Routledge.

Messerlin, Patrick and Wonkyu Shin. 2013. “The K-Pop Wave: An Economic Analysis.”

Moore, Rebekah E. 2013. “Elevating the Underground: Claiming a Space for Indie Music among Bali’s Many Soundworlds.” Asian Music 44.2: 135-159.

Novak, David. 2013. Japanoize. Music at the Edge of Circulation. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Overell, Rosemary. 2014.Affective Intensities in Extreme Music Scenes: Cases from Australia and Japan. Houndmills, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Shim, Doobo. 2006. “Hybridity and the Rise of Korean Popular Culture in Asia,” Media, Culture & Society 28.1: 25-44.

Shin, Hyunjoon. 2009. “Have you ever Seen the Rain? And Who’ll Stop the Rain?: The Globalizing Project of Korean Pop (K-Pop).” Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 10.4: 507–523.

Shin, Hyunjoon. 2011. “The Success of Hopelessness: The Evolution of Korean Indie Music.” Perfect Beat 12.2: 147-165.

Sŏng, Wan-gyŏng. 2005. “Hongdae ap indimunhwa-e kwanhan yongu” [A Study of Hongdae Indie Culture]. Master’s thesis, Inha University.

Song, Myoung-Son. 2013. “The S(e)oul of Hip-Hop: Locating Space and Identity in Korean Rap” in The Korean Wave: Korean Popular Culture in Global Context, edited by Yasue Kuwahara. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 133-148.

Straw, Will. 1991. “Systems of Articulation, Logics of Change: Communities and Scenes in Popular Music.”Cultural Studies5.3: 368–88.

Twitch, Jon W. 2015. “Return to Hell.” bRoke in Korea 21: 3, 6-7

Wallach, Jeremy. 2008. “Living the Punk Lifestyle in Jakarta.”Ethnomusicology52(1): 97-115.

Wallach, Jeremy. 2014. “‘Indieglobalization’ and the Triumph of Punk in Indonesia.” in Sounds and the City: Essays on Music, Globalisation and Place ed. Brett Lashua, Karl Spracklen and Stephen Wagg, Hampshire, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 148-161.

Notes

1 For the purposes of this article, I understand scene in the sense developed by Straw (1991: 373) as a fluid “cultural space in which a range of musical practices coexist” characterized by “the building of musical alliances and the drawing of boundaries.” As I discuss below the fluidity of this space now extends into the cybersphere and can readily overlap national boundaries.

2 English-language scholarship on indie and underground rock in Asia has focused particularly on Japan (e.g. Matsue 2008; Novak 2013; Overell 2014), Indonesia, whose punk scene is among the world’s most vibrant (inter alia, Baulch 2007; Luvaas 2013, Moore 2013, Wallach 2008 and 2014), and to a lesser extent, China (de Kloet 2005; 2010). For an insightful treatment of underground hip-hop in Korea, see Song (2013).

3 See here.

4 See here.

5 I discuss the relationship between the Korean punk scene and nationalism in greater detail in Epstein 2000, 2001, and 2006. Epstein and Dunbar (2007) offers more in relation specifically to the skinhead scene and relations with Japan.

6 Personal communication. This sentiment is echoed by Love X Stereo in various interviews.

7 Over half of the foreign residents in South Korea are from China (950,000), more than 70% of whom are ethnically Korean (Eum 2015). The number also includes a significant numbers of laborers from elsewhere in Asia, international marriage migrants, and Westerners who have come for a variety of jobs, most notably language teaching. This latter group is highly overrepresented in the Korean indie scene.

8 See here.

9 Figures involved in bringing Korean music to the outside reflect an intriguing potpourri of border crossers, including diaspora returnees such as Bernie Cho mentioned above, the CEO of DFSB Kollective. Ethnic Koreans based overseas also play a key role: Chris Park, for example, operates the koreanindie.com website out of the San Francisco Bay Area, and well-known indie musician Mike Park, who runs the influential label Asian Man Records out of a garage not far away, has been highly supportive of Korean music, having provided the narrative voiceovers for Us and Them and having toured Korea on a few occasions. Non-Koreans who do not play in bands have played an important and enthusiastic part in DIY promotion of the scene: Jon Dunbar, a long-term Seoul resident originally from Canada, has been the most active figure in documenting Korea’s punk and hardcore scene for over a decade. Support also now come from such once unlikely spots as Stockholm, where Anna Lindgren Lee, a Swedish woman married to HaSeok Lee, the manager of Korean hardcore label GMC, runs her blog Indieful ROK, and Hamilton, Ontario, home to former Seoul resident Shawn Despres, who broadcasts the radio show Sounds from the Korean Underground on local station CFMU. The show is also made available as an internet podcast.

10 In this sense, my conclusion closely resembles that of Shin (2011), although we arrive by different routes: Shin focuses on increasing attention to local spaces within a domestic context, whereas I emphasize the role of rising international interest.

11 I owe thanks to numerous people for help with this article, starting with all the bands who generously gave of their time and feature in the documentary. Annie Ko supplied additional information by e-mail, and Jeff Moses and Trash Yang Moses were particularly forthcoming with warm welcomes, engaging conversation, and some of the images that grace this article. Special thanks go to Jon Dunbar, who has developed an encyclopedic knowledge of Korean underground music over the years, and whose insightful comments on a draft have made this a better paper. Finally, I offer a special tip of the hat to my co-producer, former bandmate, academic co-conspirator and close friend, Tim Tangherlini.