Militarizing

Owen Griffiths

Introduction: War, Media, and Militarization [1]

The January 1922 issue of Shonen kurabu (Boy’s Club) carried the first episode of an exciting new “hot-blooded novel” (nekketsu shosetsu) drawn from the fertile imagination of noted children’s writer Miyazaki Ichiu.[2] For fourteen consecutive issues Miyazaki enthralled Japanese children with depictions of Japanese valour and the Yamato spirit (Yamato damashii) locked in a titanic struggle against a duplicitous and rapacious foreign enemy. The fate of the navy and of the nation itself hung in the balance. The Imperial navy fought valiantly against a technologically superior foe but was ultimately destroyed. Then, in

Finally, I locate

In all this, Japanese sentiments were remarkably similar to those of their Euro-American counterparts. The stories of

My choice of children’s media as the agents of this narrative is informed by a belief that the best way to understand the values of adults, as well as the often yawing gap between what they say and do, is to look at the process by which they transmit knowledge of all types to children.[8] As the Chinese scholar Hu Shih observed nearly a century ago, we learn much about a people by observing how they treat their children.[9] Hu Shih was referring primarily to the worlds of childrearing and education but his comments remain relevant if we expand the meaning of childrearing and education to include all adult activities where the child is the principle intended audience. Moving beyond the confines of the family, immediate community, and schoolhouse to the public spaces of print media, we can see the power the adult world has, in its broadest sense, in shaping and defining that of the child. This is where children’s print media is most salient.

Together with the formal education of the classroom and the non-formal education of the home, the informal education offered through children’s print media was the principle means by which young Japanese were socialized and prepared for adult subjecthood[10] under the Imperial realm.[11] Prior to the advent of electronic mass media in the second half of the twentieth century, print media was the main vehicle through which children were educated and socialized in the process of being entertained. Even when not overtly didactic, print media created compelling role models for girls and boys, much of which focused heavily on a manly, martial ethos. The many stories of war and future war that graced the pages of children’s magazines during this period had a significant impact on the development of prewar Japanese martial identity, one perhaps unnoticed at the time and certainly unnoticed by subsequent generations of scholars.[12]

Although children’s print media only began as a modern institution in the 1890s, publishing houses like Hakubunkan, Jitsugyo no Nihon, and Kodansha quickly recognized the commercial potential of the vast untapped children’s market. By Miyazaki’s time, children’s magazine publishers were collectively “entertaining and uplifting” children with hundreds of thousands of copies per month, ranging over history, education, science, politics, sports, romance, and of course war.[13] Due to their low cost and portability, children’s magazines transcended geography and class and therefore performed an important mediatory function linking home, school, and playground. Moreover, because children consumed this media by choice rather than by fiat, magazines reflected children’s subjective preferences to a degree that purely educational materials did not. Thus, the power of children’s print media stemmed from its uniquely commercial impulse, its function as entertainment, and its interplay with other forms of socialization and education.

From the 1890s onward, tales of martial glory, sacrifice, patriotism, and foreign perfidy drove a significant segment of children’ print media, functioning as didactic vehicles for inculcating the essential tropes of what would become the “patriotic cannon” to generations of boys and girls. Long before the ubiquitous “human bullets” (nikudan), suicide bombers (kamikaze), and the “one hundred million” (ichioku) of the Pacific War, adult writers and publishers working from a variety of motives nourished the latent national spirit of Japanese children with a steady diet of martial imagery. One consequence of this was a chillingly social Darwinistic vision of the early 20th century world order, one grounded in the zero-sum logic of grow or die, with a distinctive sense of Japanese particularism as its saviour.

Nichibei Miraisen

Nichibei miraisen is an excellent place to begin an inquiry into the nexus of media and militarization in early 20th century

Nichibei miraisen, republished with new artworks in 2006 in an electronic format

Precise circulation figures are difficult to determine for most children’s media, but Nichibei reached hundreds of thousands of children through sales of the book and the magazines alone. By 1925, Kodansha claimed to be printing 400,000 copies of Shonen kurabu monthly, selling about 275,000.[16] Its audience was boys aged 8-16, but editors always encouraged girls to read the stories, even after Kodansha started Shojo kurabu (Girl’s Club) in January 1923.[17] Through the more informal methods of lending, borrowing, or trading, circulation for Nichibei was likely much higher.[18] It became so popular that Kodansha reissued it as a single novel in August 1923 with full-page ads in both magazines announcing its impending publication.[19] The full-page advertisement in the June 1923 issue of Shojo kurabu carried large white characters reverse printed on an exploding black ball: “GREAT HOT-BLOODED NOVEL.” To the left another headline read: “Those who love the homeland must buy this!! The great struggle of hot-blooded youth!”[20] The book solidified Miyazaki’s reputation as the premier writer of “hot-blooded novels” and helped make Kodansha the leading publisher of children’s fiction in the prewar years with Shonen kurabu and Shojo kurabu leading the way.[21] Indeed, Miyazaki held a virtual monopoly over the “hot-blooded” label with both Kodansha and Hakubunkan until his mysterious death in 1934.[22]

Miyazaki’s tale of future war began its serialized run in February 1922, the same month Japan’s representatives signed the Washington Naval Treaty with the other “great powers,” which established the “5:5:3” ratio of capital ships for the United States, the British Empire, and Japan respectively.[23] The juxtaposition of fact and fiction was not accidental or new. Riding the wave of public dissatisfaction about the Washington Treaty to great advantage,

Set about ten years in the future, Nichibei opens in Sasebo Harbour with the navy’s launching of eight new battleships to complement its eight existing battle cruisers: The “Hachi hachi kantai” (The 8/8 Squadron).[24] The story begins:

The Navy’s hachi/hachi kantai was at last ready. It had taken more than ten years and one third of each year’s total national expenditures… Despite the underhanded and detestable meddling of the United States, which had overtaken England as the world’s number one naval power, and the interference of Japanese politicians and their arguments for arms reduction, the construction of the new squadron had succeeded. … Throngs of people lined the docks of

The adventure now unfolds rapidly as the entire fleet slips its moorings under the cover of darkness and vanishes. Witnessing the departure from a hill above the harbour are retired Admiral Nango and his teenaged grandson Takuji, the story’s protagonist.[29] The old man turns to his grandson and orders him into action as planned. The next day’s newspaper headlines scream, “Break in Diplomatic Relations! Outbreak of US-Japan War! Combined Fleet Departs

Episode two treats readers with a brief lecture on modern international relations before turning to the battle. Still remaining in the fictional framework of future war,

The first attack comes from the air, as American planes bombard

Here, the story shifts to a Shishigashima (

The scene again shifts to the deck of an enemy ship as two American officers boast about how they can easily sail right up to “the little monkey country of Japan” now the Japanese fleet has been destroyed.[37] As they talk of conquering Japan’s Asian possessions and possibly even the archipelago itself, massive explosions rock the ship and it begins to sink. Suddenly, ships throughout the fleet are sinking. The Americans panic and begin firing wildly in all directions. “Monsters like giant white snakes appear and disappear through the driving rain and massive waves.”[38] They are none other than the new submarines, designed and built by the “iron arms” of Azuma and led by the young boy warrior Takuji. Unexpectedly, however, disaster strikes as an errant shell cleaves the command sub in half, throwing Takuji into the “cruel black sea.”[39] Compassion for a fallen comrade drives Rear Admiral Soda to split the submarine squadron. Half will search for Takuji while the others engage the US Atlantic Fleet in a “decisive battle.” “Can the squad defeat the mighty Americans? Will Takuji be saved?”

The final episode finds Takuji clinging to a piece of flotsam, fortuitously given him by another adrift Japanese sailor just before a giant wave separates them. The selflessness of the sailor is rewarded as the search succeeds and Takuji is saved. Readers never learn the fate of that valiant sailor. After being taken aboard ship, Takuji learns that the other half of the squadron has completely destroyed the enemy and saved the nation. Takuji utters quiet thanks and the crew rejoices. Across the Pacific, the Americans react with shock and anger on hearing the news. Some allege that

Meiji Antecedents of Future War

This abridged version of Nichibei highlights a number of themes common to the war-as-entertainment genre, all of which trace their roots back to earlier practices. The first concerns an adult understanding of the international world as one of endemic conflict where the strong devour the weak, where, as Thucydides said two millennia ago, “the powerful exact what they can, and the weak grant what they must.”[42] In the world of Taisho

Do not expect that mysterious sea snakes will always appear to save the nation. Had they not done so at that time,

The pedigree of these ideas dated back to the heady days of nation building in the Meiji era. Here, too, fiction played a central role. One of the main prototypes of future war was the “political novel” and Yano Ryukei’s 1890 Ukishiro monogatari (The Floating Battleship) in particular. Although Yano wrote Ukishiro for an adult audience, later generations of children it seems read the story with great enthusiasm.[45] Considered by some to be the first work of science fiction in modern Japan, Ukishiro became a standard for later war and future war fiction: Young, male uber-patriots embark on a South Sea adventure to “open up a giant territory tens of times the size of Japan and offer it to the Emperor…”[46] Like Miyazaki’s heroes, Yano’s adventurers are motivated by a deep dissatisfaction with Japanese passivity in the face of overwhelming foreign power. When Captain Sakura addresses his men early in the story, he says:

“The Western race carries out its exploits throughout the entire earth while the Japanese people carry out their exploits within their own country. We shouldn’t put up with such a lamentable predicament… Indeed, we should take this entire earth as our stage and carry out a great enterprise of singular proportions. Why does Japan alone need to cower in fear and move stealthily about”[47]

In this fictional address we can see strong parallels to

While the roots of children’s future war fiction can be found in the political idealism of 1880s adult fiction, early producers of this media also drew heavily on two older, indigenous traditions, one martial and one other moral. The moral imperative was kanzen/choaku (rewarding good and punishing evil), which has proved to be a durable concept in children’s writing throughout the 20th century. A good example of this was Iwaya Sazanami’s Shin hakken den (The New Biography of Eight Dogs) serialized in Shonen sekai in 1898.[49] Based on Takizawa Bakin’s Edo-era novel Nanso satomi hakken den (Biographies of Eight Dogs), it was a tale of eight young boys who traveled to a South Sea island and, through a series of daring adventures, came to rule over it. The original story, set in

Nanso Satomi Hakkenden, the original first print

In its modern incarnation, the martial imperative first intersected with the moral imperative of kanzen choaku with the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War in 1894. From its inaugural issue on January 1, 1895 until war’s end, Iwaya’s Shonen sekai carried a variety of stories of the war in each monthly issue, including reports from the front, accounts of bravery in battle, and tales drawn from

Modern Children’s Media in the Crucible of War

Iwaya Sazanami (1870-1933) stands as a giant in the world of modern Japanese children’s literature and is considered by many scholars to be the true pioneer of the field and the first to devote his entire professional life to the development of children’s media.[52] At the tender age of nineteen, Iwaya wrote what many consider to be the first full-length modern novel for children, Kogane maru (The Courageous Dog Kogane) in 1891.[53] It launched Iwaya on a career that would earn him the affectionate titles of “Uncle Fairy Tale” (Otogi Ojisan) and “Uncle Iwaya” from generations of adoring children by the time of his death in 1933. In addition to his many koen dowa and his popular collections of Japanese fairy tales (Otogibanashi), Iwaya also became Japan’s leading authority on Hans Christian Anderson and the Brothers Grimm, on whose works he laboured and lectured for many years.[54] His interest in Northern European folk and fairy tales placed him firmly at the centre of a growing Japanese interest in German letters among well-educated elite.[55] Iwaya’s intellectual and cultural affinity with Germany was reflected in the attitudes of another giant of children’s print media, Kodansha founder Noma Seiji.[56] The careers of both men career also suggests a powerful sense of commitment to the values of education, progress, and a profound attachment to the idea of Japan as a modern, masculine, and martial nation. This sentiment was evident in Iwaya’s fairy tales and storytelling performances but even more expressly in the pages of Shonen sekai (Boy’s World) he founded in 1895. Published by Hakubunkan, Shonen sekai was one of the first children’s magazines in modern

Even before Shonen sekai’s debut, Hakubunkan published two special issues on the Sino-Japanese War for children in October and November of 1895, both of which provide a clear idea of what was to come. Titled Yonen zasshi (Children’s Magazine), and edited by Iwaya himself, these two publications gave up to date accounts of Japanese bravery and valour. The November issue carried a story entitled “A Verbatim Account of Hell in the Sino-Japanese War.” This was the heroic tale of Captain Matsuzaki Naoomi, said to have been the first Japanese commissioned officer to die in the Sino-Japanese War on July 29, 1894.[59] The story opens with a group of dead Chinese soldiers on their way to hell. As they approach the River Styx (Sanzu no kawa), Captain Matsuzaki overhears and surprises them, at which point they flee across the river in fear. Laughing heartily, Captain Matsuzaki muses that nothing can be done for them and decides to head for heaven. Drawing heavily Buddhist metaphors, all of which would have been familiar to Japanese boys, the story contrasts the brave and cheerful Matsuzaki, even in death, on his way to his Edenic reward for faithful service to the Emperor/nation, with the scared, bumbling Chinese soldiers whose only fate is Hell.[60] Even Shonen sekai writers on non-military topics seemed compelled to offer their thoughts on the army’s victories in battle. Owada Takeki, for example, began his regular column on literature by telling readers how the recent, decisive victory of the Imperial forces “moved him deeply.”[61]

The deification of Captain Matsuzaki was quickly followed by other heroes from both the Sino-Japanese and Russo-Japanese wars like the resolute

An episode in

“’Hey, Yankees (Yôki)! I expect you’ve heard of Japanese hara-kiri but you’ve never seen it performed have you. Well, Onuki’s gonna show you!’ With that, he pulled open his tunic and grasping firmly his precious Japanese sword he thrust it deep into his right side. The sword sliced through his flesh as he pulled it across his body. Grasping his beloved flag, he then stuffed it into the gaping wound he had just made. That fine fellow died a brave and unparalleled death. When the American troops arrived they froze in terror at the sight.”[63]

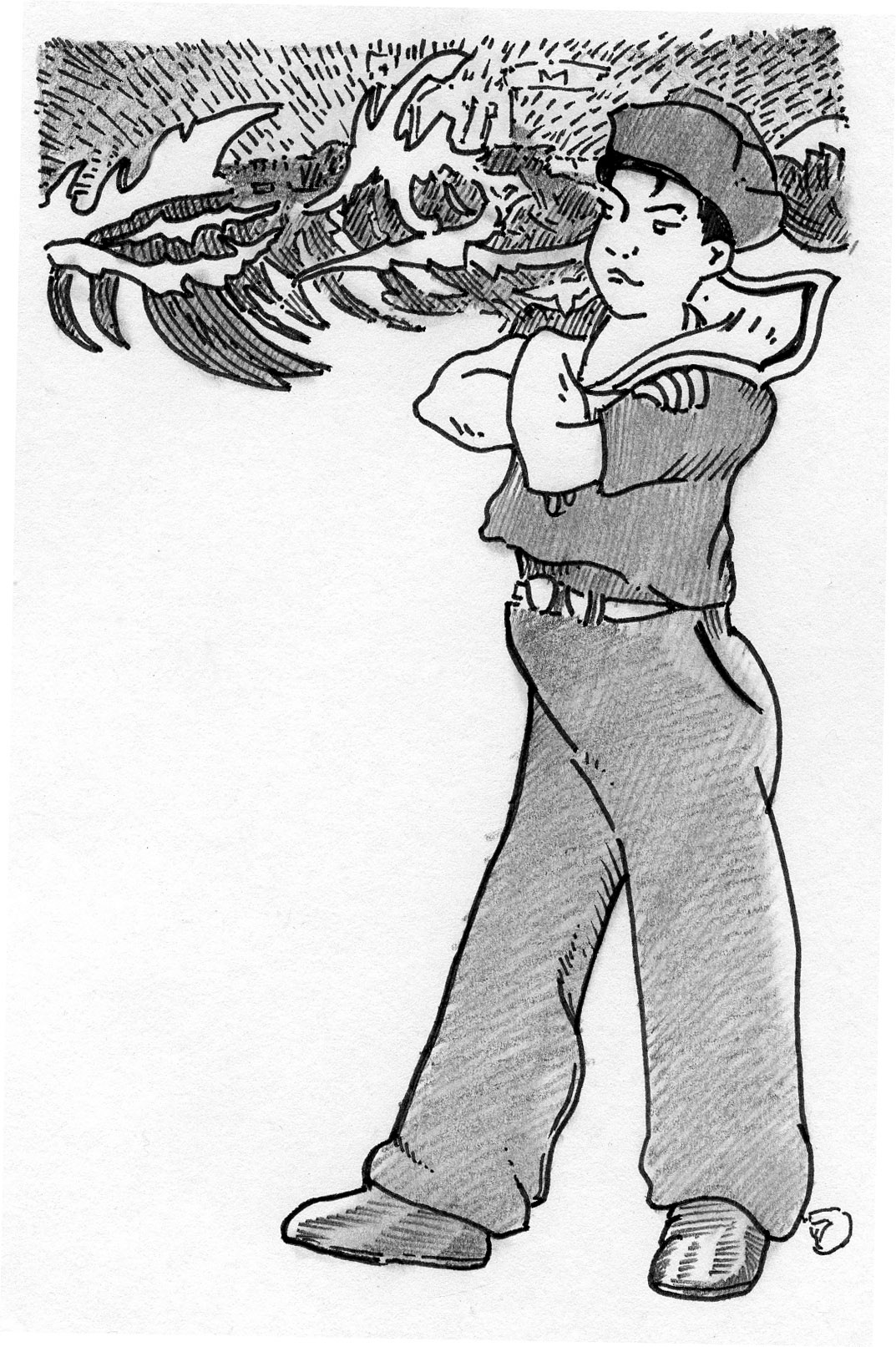

Onuki Committing seppuku [64] (Reproduction credit: Peter Manchester)

To kanzen choaku and the pantheon of past martial heroes, all excavated from

Two points are noteworthy here. The first is the fascinating blend of fact (the battleship Chiyoda and the Battle of the Yellow Sea), fiction (the story of the young Chiyodai), and fantasy (the Palace of the Sea God, the princess, and elder Matsue’s reincarnation as the king of the Sea), all of this from the man who later gained fame as a Japanese playwright in the manner of Oscar Wilde.[67] This blending of fact, fiction, and fantasy became a staple in Japanese children’s literature throughout the prewar years. The second point relates to the centrality of children as the main protagonists of the stories. Sometimes they were depicted sacrificing and dying for their country, as with young Chiyodai. In others the heroism and death of adults, usually family members, was portrayed through the eyes of the child heroes as in

Takuji, the child warrior[70] (Reproduction Credit: Peter Manchester)

In depicting the deaths of children or adults as acts to be glorified and praised, the media was not alone. Textbooks also immortalized and beautified death in war. Most commonly this was portrayed through the protagonist dying happily with a smile on his lips. One volume of the 1900 textbook series Shinhen shumiten (New Teacher’s Guide to Moral Training) carried a story entitled “A Sailor Named Mitsushima Kan” (Mitsushima kan no suihei) set during the Battle of Yellow Sea in the Sino-Japanese War. On hearing of the destruction of an enemy ship the mortally wounded Mitsushima exclaimed, “I’m so happy…then with a bright smile on his lips, Mitsushima died.”[71] Taken together, magazines and textbooks appropriated older samurai traditions of “dying well” and placed them in the contemporary context of wartime to create compelling role models to which Japanese boys could aspire. These kinds of stories were not aberrations of the last, desperate days of the Pacific War but were rather borne in the victories of modern

The manner in which the Sino-Japanese War was fictionalized and presented as entertainment for children became the prototype for constructing a manly, martial ethos throughout the first half of the 20th century. Indeed, the Sino-Japanese War was the first to be “textualized” specifically for children. Much has been written about

Tales of war and patriotism proved highly profitable throughout the world of print media. Just as the war encouraged competition and innovation among producers of adult magazines and newspapers, so, too, did it drive a similar process in children’s media. Competition between Hakubunkan’s Yonen sekai (Children’s World) and Shonen sekai and Jitsugyo no Nihon’s Nihon Shonen (Japan Youth) and Shojo no tomo (Girl’s Friend) led the way in the 1890s, driving innovation and market expansion and creating a highly commercialized and profitable children’s print media that had scarcely existed a decade earlier. Into this growing and profitable field stepped a young Oshikawa Shunro with a new adventure story, modeled on Yano’s Ukishiro and written while still a student at Tokyo Semmon Kakko (Waseda) where he studied politics.[74] A relative introduced Oshikawa to Iwaya who loved the young man’s new story and quickly took him under his wing at Hakubunkan.[75] With a preface written by Admiral Ito Yuko, a veteran of the Sino-Japanese War, Oshikawa’s new adventure novel Kaitei gunkan (The Submarine Battleship) made its debut in 1900.[76] The novel was a huge hit among boys 8 to 15. Almost overnight Oshikawa had created a new genre of children’s stories known as the adventure novel. Despite a career cut short by personal tragedy and illness, Oshikawa occupies a preeminent position in the history Japanese children’s media. He exerted a profound influence on

Kaitei gunkan was actually part of a six-novel series published between 1900 and 1907, all of which took as their point of departure Japanese passivity in the face of predatory foreign imperialism. Kaitei gunkan traces the exploits of a disgruntled former naval officer Captain Sakuragi and his hardy band of patriots who build a new submarine battleship on a secret island. The ship, the denkopan is submersible, capable of flight and is armed with futuristic torpedoes and a new ramming technology. Throughout the series, Sakuragi and his men battle the Russians, the French and the English, destroying them all. They even fight on the side of Filipino “freedom fighters” against American imperialists. Written before, during and after the Russo-Japanese War, Oshikawa’s novels rode the rollercoaster of war fever and then disgruntlement over the treaty that followed. In the process, he introduced thousands of Japanese boys to adult concerns about

According to Ito Hideo, Oshikawa’s purpose was to “oppose those who oppressed freedom” and to inculcate in young readers “the spirit of resistance at all costs”[78] Yet neither Ito nor Oshikawa himself acknowledged

Oshikawa then went on to lament the decline of bushido damashii since the Russo-Japanese War, singling out excessive pride, conceit, socialism and naturalism as the principle domestic evils. The youth of

The idea of war helping to drive the popularization of mass media in early 20th century

Cultures Collide: Martiality in

Like all things Meiji, children’s print media developed from a fascinating blend of indigenous styles and practices, critiqued and reconstructed with foreign ideas and importations. As Oshikawa drew on Yano and Iwaya and then in turn influenced

Lea wrote The Valor of Ignorance to shake Americans out of their complacency and to convince them that the romantic ideal of republican martial virtue expressed in the militia was hopelessly out of date. Modern wars, he said, required the “conversion of the nation’s potential military resources into actual power… by men more scientifically trained than lawyers, doctors, or engineers.”[89] Disparaging volunteers as a mediaeval institution,” Lea maintained that the “soul of the soldier” could not be molded “in twenty-four days by uniforming a volunteer” but took “not less than a dozen men six-and-thirty long months to hammer and temper him into the image of his maker.”[90] This necessitated “a relentless absorption of individuality” and “an annihilation of all personality.” Sounding much like Oshikawa, and later future war writers like

That Lea’s ideas animated the thinking of military men, including those in

Militarization, Media, and Mirrors

While this is essentially a Japanese story, the process by which it unfolded and the ideology that animated it were by no means unique to

Until World War II a wide range of individuals and groups throughout the industrializing world preached the gospel of militarism and militarization, often in the stated interests of preserving peace. Since 1945 militarism and militarization have understandably taken on a more pejorative tone, despite the fact that the gospel of military preparedness was never more systematically spread than during the cold war: and now again in the current war on terror. C. Wright Mills may have been one of the first to recognize this postwar shift in the 1950s when he spoke of a new “military definition of reality” throughout

In the last couple of decades, scholars and activists have begun to reexamine and refine the relationship between militarism and militarization, usually from a feminist perspective. Cynthia Enloe, a pioneer in this area, argues that “[m]ilitarism is an ideology. Militarization, by contrast is a sociopolitical process… by which the roots of militarism are driven deep down into the soil of a society.”[104] Moreover, she maintains that militarization is “a tricky process” because virtually anything can be militarized at any time, in war or in peace. Thus, for Enloe, militarization occurs “when any part of a society becomes clearly controlled by or dependent on the military or on military values.”[105] In a similar vein, Michael Geyer, argues that militarization is a “contradictory and tense social process in which civil society organizes itself for the production of violence.”[106] More recently, Catherine Lutz echoes Geyer’s definition in her study of Fayetteville North Carolina, home of Fort Bragg, focusing particularly on the development of modern war and its relationship to industrial capitalism and the nation state.[107] These scholars demonstrate the importance of analyzing militarism and militarization in terms of the relationships between power, gender, and violence and between industrial capitalism and the nation-state. They also demonstrate the utility of seeing both ideology and process through feminist lenses.

The work of these scholars alerts us to dangers in our own world, but their comments also apply equally to the world of prewar

This last category is particularly important because in

“authentic” male experience of war. Anchoring this is the idea of sacrificial death as the ultimate expression of these values, what Lea called, “the pinnacle of human greatness.”[110] The focus on dying as the ultimate sacrifice in Japanese future war also served to exclude females, at least until the end of the Pacific War. In prewar Japanese war adventures there were many girl heroes but few died and never in battle.[111] Men and boys, by contrast, died by the shipload. This form of gendered nationalism carried right through to the last desperate days of the Pacific War, by which time everyone was expected to die. Still, echoes of the prewar division of gender based on who died in battle remained as late as 1945. Kodansha’s New Year’s 1945 issue of Shonen kurabu, for example, carried Bakumatsu era poems about women dreaming of being reborn as men so they could die for the emperor.[112] The February 1945 issue even contained a young girl’s letter to the editor in which she said, “If I were a boy, I too could join the shimpu.”[113] It is difficult to know whether letters like these were actually written by girls or merely fabricated by the magazine’s editors. Either way, they do reveal a deeply gendered conception of war and death, one that was largely monopolized by males.

As Geyer and Enloe have noted militarization occurs wherever a class, caste, or other social group reserves for itself the right and responsibility to use violence. Monopolizing the right to use violence is a core component of the classic definition of the state, dating back at least to Max Weber. Charles Tilly has argued that states or other agents who produce “both the danger and, at a price, the shield against it” are effectively racketeers.[114] This is a reasonable description of what many adult producers of children’s media did in Japan and, sadly, what some leaders continue to do in our contemporary world. The producers of children’s war adventures created the danger (national destruction) and the solution (martiality and yamato damashii). The price was, to quote Lea again, the “annihilation of all personality” in selfless devotion to the nation. Seeing

Men like Iwaya, Oshikawa, and

Men make their own history, but they do not make it just as they please; they do not make it under circumstances chosen by themselves, but under circumstances directly encountered, given, and transmitted from the past. The tradition of all dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brain of the living. And just when men seem engaged in revolutionizing themselves and things, in creating something entirely new… they anxiously conjure up the spirits of the past and borrow from them names, battle slogans and costumes in order to present the new scene of world history in this time-honored disguise and this borrowed language.[116]

For Marx, this tendency was the bane of human existence, drawing us into the past at the very moment when we should be breaking with that past in an effort to construct a new future. The adult producers of

Owen Griffiths is Associate Professor of History,

_______________________________

Endnotes:

1. I would like to thank the Social Science and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) for its generous support in providing funding for this project.

2.

3. Miyazaki Ichiu, “Nichibei miraisen,” Shonen kurabu, November 1922, 67. Hereafter referred to as Nichibei.

4. Although I focus principally on

5. This phrase comes from the title of I. F. Clarke’s collection of Euro-American future war stories. The Tale of the Next Great War, 1871-1914,

6. The best discussion of this subject is I.F. Clarke, Voices Prophesying War: Future Wars, 1763-3749, Oxford University Press, 1992. For a more American focus on the same subject, see H. Bruce Franklin, War Stars: The Superweapon and the American Imagination, Oxford University Press, 1988.

7. T. J. Jackson Lears,

8. Any use of the term media must always refer to a plurality of agents, whose reciprocal interactions with the public and with each other is complex, contested, and competitive. The media can never be usefully understood as a monolithic entity. This is especially true during the formative period of its development, as with the print media in

9. Hu Shih, “Tz’u-yu te wen t’i,” Hu Shih wen-ts’un, p. 739, cited in Ping-chen Hsiung, A Tender Voyage: Children and Childhood in Late Imperial China, Stanford University Press, 2005, xiv. Hu Shih said that any society could be understood by the way its people treat their children and their women, and how they spend their leisure time.

10. Despite much public discussion of citizenship during this period, the Japanese people under the Meiji Constitution were subjects not citizens. Citizenship only emerged as a result of popular sovereignty finally being enshrined in the people under the postwar constitution.

11. This three-fold division comes from Edward Beauchamp, Education and Ideology in Modern

12. Exceptions in

13. The relationship between formal education and print media during these years is a fascinating and complex subject in its own right, but one to which I cannot do justice here. However, there are three areas of convergence between the two that are central to my story. The first is that education and media were both products of the same processes of mass production and consumption. The second is the important role played by education in creating a readership for all print media through rising literacy rates. The third is the remarkable continuity between both institutions in terms of their focus on war, patriotism, and the need for building a martial, manly society. Future war fiction, however, seems to have been exclusive to print media. The intersection of formal education and print media was best exemplified in the person of Kodansha founder Noma Seiji (1878-1938). In a 1938 eulogy to Noma, Tokutomi Soho referred to him as

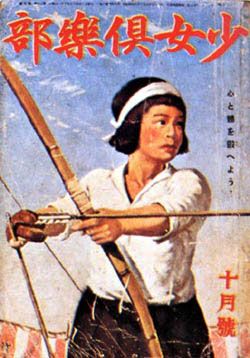

14. Thus far in my research, I have focused primarily on boy’s magazine where the martial, manly ethos was understandably most prominent. However, historical and contemporary stories focusing on war and foreign perfidy were also prominent in girl’s magazines. In fact, many writers,

15. I am currently working on a quantitative assessment of national coverage of Shonen kurabu and Shojo kurabu based on the letters to the editor published monthly in both magazines. These letters, which came from every prefecture, may not necessarily reflect actual circulation patterns but they do provide insight into Kodansha’s strategy of representing its magazines as truly national in scope.

16. These are the official figures from Kodansha Hachijunenshi Henshu Iinkai, Kuronikku Kodansha no hachijunen (Eighty Years of Kodansha), Kodansha, 1995, 116.

17. Kodansha, Shojo kurabu was printing 380,000 copies by 1925 and selling 188,710. Both magazines sold for 60 sen per copy. Ibid., 116.

18. The editors of Shonen kurabu actively encouraged this practice, regularly using its Tayori column to instruct young readers to pass on their magazines or to form reading clubs so they could enjoy the stories together.

19. Miyazaki Ichiu, Nichibei miraisen, Dainihon Yubenkai/Kodansha, 1923.

20. Shojo kurabu, June 1923, 三ã®A. Shonen kurabu also carried ads in at least two of its issues for the upcoming book. Given that both magazines were published by Kodansha, it is not surprising that the tone and language of the advertisements was the same. Nonetheless, from a gender perspective, it is interesting to note that the same basic message was directed toward both boys and girls.

21. Ueda Nobumichi, “Miyazaki Ichiu no Jidobungaku (“The Children’s Literature of Miyazaki Ichiu”) Kokusai Jidobungakkan kiyo, No. 8, March 31, 1993, 8. Available in full text online here, accessed May 14, 2006.

22.

23. The actual ratio of capital ships permitted under the treaty was as follows:

24. Of the eight, four were of the Nagato class (Nagato, Mutsu, Saga, and Tosa), two were of the Ise Class (Ise and Hyuga), and two were of the Fuso Class (Fuso and Yamashiro). Taken from Nichibei, January 1922, 49-50.

25. Ibid., 48-49. Here, I want to thank Takahashi Kazuko for her valuable assistance in reading this story. Unless otherwise noted, however, all translations are mine.

26. Ibid., 50.

27.

28. Although

29. Admiral Nango was, of course, none other than Admiral

30. Nichibei, January 1922, 55.

31. Nanyo was the phrase given to the

32. Nichibei, February 1922, 79-80.

33. Ibid., August 1922, 48-49.

34. Ibid., November 1922, 67.

35. The Unebi was a French-built cruiser commissioned by the Japanese navy in December 1886. Three months later it disappeared at sea with all hands lost en route from

36. Ibid., December 1922, 68.

37. Ibid., 72.

38. Ibid., 73.

39. Ibid., 77.

40. At this time, international treaties did not forbid submarine warfare except with regard to merchant vessels, the sinking of which was governed by the same rules as those covering surface naval warfare. The main treaty covering submarine warfare was “The Treaty Relating to the Use of Submarines and Noxious Gases in Warfare,” signed on February 6, 1922 as part of the Washington Conference negotiations. This treaty was never put in force, however, because

41. Ibid., February 1923, 87.

42. This phrase comes from Thucydides in his reconstruction of the dialogue between the Athenians and the Melians after the former had defeated the Melian’s ally Lucaedamon, reprinted from here, accessed September 15, 2006.

43. Nichibei, February 1923, 88. Oyashima comes from the Nihonshoki and refers to the original eight islands said to have been created by Izanagi and Izanami. Italics mine.

44. The idea of

45. Torigoe Shin and Nemoto Masagi make this point but without any supporting data in “Oshikawa Shunro to Tachikawa Bunko” Nihon jido bungakushi (A History of Japanese Children’s Literature), Mineruba Shobo, 2003, 108.

46. Yano Ryukei. Ukishiro Monogatari. (Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 1940), quoted in Xavier Bensky, “Dynamite Don!”: Radical Students, Patriotic Youth, and Science Fiction Novels in the Meiji Era, A paper presented at the Association for Asian Studies Chicago, IL, 2005, 9. I would like to thank Xavier for providing me with a copy of his paper. Robert Matthew maintains that Ukishiro was the first Japanese science fiction story in Japanese Science Fiction: A View of a Changing Society, The Nissan Institute/Routledge Japanese Studies Series, 1989, 10-11.

47. Quoted in Bensky, “Dynamite Don!,” 8.

48. Ibid., 10.

49. This account comes from Hasegawa Ushio, Jido senso yomimono no kindai (Modern Children’s Wartime Media), Nihon Jido Bungakushi Sosho, No. 21, Hissayamasha, 1999, 15-16.

50. Hasegawa, Jido senso, 18-19.

51. This point is made by James L. Huffman, Creating a Public: People and Press in Meiji Japan,

52. There is some debate among Japanese scholars as to Iwaya’s place as modern pioneer of children’s fiction. Some reject this title, arguing that Iwaya was not so much modern pioneer as he was popularizer of older

53. A tale of a dog who avenges the death of his father by a tiger with the help of another canine, Kogane maru reflected Iwaya’s own literary heritage, particularly the centrality kanzen choaku and his membership in the Kenyusha (Friends of the Inkstone), an elite literary group centring around Ozaki Koyo (1867-1904) and counting as its members Izumi Kyoka, Takase Bunen, and Hirotsu Ryuro. The Kenyusha was the dominant literary group in

54. Koen dowa were stories told aloud. Iwaya drew on both indigenous and foreign traditions to construct his modern versions of these.

55. The powerful Japanese attraction for German philosophy and political theory is a fascinating subject in its own right. While there is no space to discuss this here, readers should note that the attraction was not merely a matter of cultural borrowing for its own sake but reflected a deep Japanese predisposition for German ideas that was rooted in

56. The impact of Noma and Kodansha on the development of children’s print media comprises a separate chapter of my larger project. For more on Noma and Kodansha in Japanese, see Sato, ‘Kingu’ no jidai and Noma’s own autobiography Watashi no hansei (Half My Life), Kodansha, 1936, also republished as Shuppan kyojin sogyo monogatari: Sato Giryo, Noma Seiji, Iwanami Shigeo, (Founding Tales of the Great Publishers), Shoshi Shinsui, 2005. A hagiographical treatment in English is Shunkichi Akimoto, Seiji Noma, ‘Magazine King’ of

57. I have not been able to obtain accurate circulation figures but Shonen sekai’s longevity alone, compared with that of most other children’s media until the WWI years, suggests its dominance through the mid-1910s. This was certainly the official position of Hakubunkan as can be seen in Tsubotani Yoshiyoro, Hakubunkan gojunenshi (A Fifty-year History of Hakubunkan), Hakubunkan, 1937.

58. Nihon Kokkai Toshokanhen, Zasshi Mokuroku, vol. 3, Nihon Kokkai Toshokan Henbu, 1981, 1701.

59. Captain Matsuzaki’s exploits were later immortalized just before the second Sino-Japanese War in 1937 with the publication of Tsuji Zennosuke (ed), Ruishu denki dainihonshi (Collected Biographies from Imperial Japanese History), Yusankaku, 1935-1936.

60. The basic storyline comes from Hasegawa, Jido senso, 16-17.

61. Ibid., 19.

62. “Sansho wa kotsubu demo piriri to karai,” Nichibei, July 1922, 34. Sansho is a Japanese pepper.

63. Ibid., 36-37. Visual images of men committing seppuku were not uncommon in war and historical novels at this time. I have found examples in both girl’s and boy’s magazines throughout the 1920s and 1930s.

64. Ibid., 36-37. The original artist for the illustrations in Nichibei was named until the September 1922 issue when Yamada Rikken’s name appeared in each subsequent issue.

65. Hasegawa, Jido senso, 19. Huffman discusses this as well in Creating a Public, For a discussion on Kunikida’s place in modern Japanese literary history, see, Edward Fowler, The Rhetoric of Confession: Shishosetsu in Early Twentieth-Century Japanese Fiction, University of California Press, 1992, 74-75, 86-93, and Jay Rubin “Kunikida Doppo,” Ph.D. diss., University of Chicago, 1970 and Injurious to Public Morals. Fowler is only English-language literary scholar I have encountered who discusses the contributions to children’s literature made by many Meiji writers before they attained fame as producers of adult fiction.

66. This account is taken from Hasegawa, Jido senso, 19-20.

67. Kyoka’s penchant for the fantastic and the bizarre is revealed in M. Cody Poulton, Spirits of Another Sort: The Plays of Izumi Kyoka,

68. Hirotsu was also a Kenyusha member. The Kenyusha presence suggests a number of interesting points of analysis I am unable to explore here. It seems clear that Iwaya actively sought contributions from members of his own group, who were in turn happy to earn some income in the early stages of their careers. In terms of legacy, children’s fiction draws a fairly straight line from the Kenyusha men who embraced the concept of playful composition (gesaku) and kanzen choaku. This is in contrast to the naturalist movement that overtook the Kenyusha group, the adherents of whom rarely entered into the field of children’s fiction.

69. Hasegawa, Jido senso, 20-21. This story reflects a gendering trend in children’s media common to all martial traditions that permitted only Japanese boys to anticipate their fate in battle. Girls and women were relegated to support roles of nurturer or nurse whose ability to face the enemy in battle had to await their rebirth as males. This support role was not modern but the creation of new institutions like the Red Cross gave it a particularly modern focus.

70. Nichibei, November 1922, 66.

71. Quoted in Hasegawa, Jido senso, 98.

72. See Ibid., 19 and James Huffman, Creating a Public, 199-224.

73. This point is made by many including Huffman, Creating a Public and Rubin, Injurious to Public Morals.

74. Torigoe says that Kaitei gunkan’s enormous popularity since its publication in 1900 may have created renewed interest in Ukishiro among young readers. Torigoe Shin and Nemoto Masagi, “Oshikawa Shunro to Tachikawa Bunko,” 108-09.

75. Ibid., p. 111.

76. Oshikawa Shunro, Kaitei gunkan, Hakubunkan, 1900. Ito participated in the

77. Between 1911 and 1912 Oshikawa lost his two sons to illness, turned to drink and died in 1914 from acute pneumonia. Although his mentor Iwaya is better known in

78. Ito Hideo, Shonen shosetsu taikei, vol. 2, Sanichi Shobo, 1987, quoted in Torigoe Shin and Nemoto Masagi, “Oshikawa Shunro to Tachikawa Bunko,” 109.

79. Oshikawa Shunro, “Keikai subeki Nihon” (A Warning for Japan), Boken sekai, December 1910, reprinted in Meiji daizasshi fukuenpan (Meiji Reprint Series of Great Magazines), Ryudo Shuppan, 1978, 174-179.

80. Ibid., 174.

81. Ibid., 174.

82. Ibid., 176.

83. Ibid., 177.

84. Ibid., 178. Oshikawa never identified these enemies clearly but he seemed to be taking aim at the middle classes and all those who supported democratic ideals or any form of egalitarianism.

85. English and Japanese sources generally agree on the importance of Verne and Wells on the development of war adventures and science fiction in but only the Japanese sources have linked this specifically with children’s media. In English, see Susan J. Napier, The Fantastic in Modern Japanese Literature: The Subversion of Modernity, Routledge, 1996 and Robert Matthew, Japanese Science Fiction: A View of a Changing Society, Routledge, 1989.

86. A good general discussion of Euro-American literary influences on Meiji Japan is Hirakawa Sukehiro, “Japan’s Turn to the West” (trans. Bob Wakabayashi), Cambridge History of Japan, vol. 5, The Nineteenth Century, Cambridge University Press, 1989, 432-498.

87. Lea is a fascinating but relatively unknown character in modern history. Not quite five feet tall, hunchbacked, and dismissed from West Point due to ill health, Lea nonetheless managed find the martial life he so desperately sought, leading a ragtag group of Chinese soldiers against the Boxers in 1900 before fleeing to Hong Kong and Japan with a price on his head courtesy of the Empress Cixi. In Japan Lea sought out Sun Yat-sen who was so impressed by the little man, he promised to make Lea his chief military adviser. Sun finally made good on his promise ten years later. With the proclamation of the

88. Ike Ukichi, Nichibei senso, Hakubunkan, 1911. This information comes from Ueda Nobumichi, “Taisho ni okeru nichibei miraisenki no keifu” and Rees, “Homer Lea.” The Valor of Ignorance received mixed reviews in the

89. Homer Lea, The Valor of Ignorance, (Harper and Brothers, 1909), Simon Publications 2001, 47.

90. Ibid, 48, 52, 56.

91. Ibid., 52-53.

92. Ibid., 76.

93. Ibid., 82.

94. Ibid., 66.

95. Lea never explained why

96. Quoted in Hasegawa, Jido senso, 80.

97. Another example of this plotline is Abu Tempu’s future war classic “Taiyo wa ketteri” (The Sun Victorious) serialized in Shonen kurabu from January 1926 until Abu’s untimely death in November 1927.

98. Kuwahara, Shonen kurabu no goro: Showa zenki no Jido bungaku (The Age of Boy’s Club: Early Showa Children’s Literature), Keio Tsushin, 1987, 91-93.

99. By “trace” I mean create in the sense that among all the stories we tell ourselves about our origins a significant number relate to war. This is particularly true of national histories of the last 100 years and also of the manner in which we teach our children in the classroom.

100. C. Wright Mills, The Power Elite,

101. Ibid., 223.

102. The entire speech is reproduced here. Cited September 12, 2006.

103. Ibid.

104. Cynthia Enloe, The Curious Feminist: Searching for Women in a New Age of Empire,

105. Cynthia Enloe, “

106. Michael Geyer, “The Militarization of Europe, 1914-1945,” in J. R. Gillis (ed.), The Militarization of the Western World, Rutgers University Press, 1993, 79.

107. Catherine Lutz, “Making War at Home in the

108. This statement corresponds to Enloe’s first three of seven core beliefs of militarism as an ideology: “a) that armed force is the ultimate resolver of tensions; b) that human nature is prone to conflict; c) that having enemies is a natural condition.” Ibid., 219. Clearly the interpreters of Lamarck and Darwin have much to answer for.

109. A good discussion of the perceived dangers new definitions of womanhood and femininity posed to Japanese conservatives in the 1920s and 1930s is Barbara Sato, The New Japanese Woman: Modernity, Media, and Women in Interwar

110. The focus on death also serves to deflect attention away from the fact that in war one also kills. To say that one has died for a cause (for “us,” for example) is psychologically more satisfying and acceptable than to say that one has killed for that same cause. He who dies is a martyr or hero and retains a degree of humanity that he who kills does not. And until recently this has meant man against man. In the vast, linked systems of war and its remembrances constructed by most countries in the last century –

111. Girls’ magazines like Shojo kurabu and shojjo no tomo published no future war stories that I have found, although they did advertise them to girls. There were, however, numerous adventures with girl protagonists who were usually motivated to solve a mystery because of the death of a male relative. One example is

112. Kimata Osamu, “Bakumatsu aikoku josei no uta: Minatogawa kiyoku nagareshi” (Songs of Female Patriots of the Bakumatsu Era: The Minato River flows purely) Shojo kurabu, January 1945, 5-7.

113. This letter was published by Goto Shosa of the War Ministry’s Information Bureau under the title “Kamiwashi o miokuru” (Bidding Farewell to the Divine Eagles), Shojo kurabu, February 1945. 19.

114. Charles Tilly, “War Making and the State as Organized Crime,” in Peter B. Evans, Dietrich Rueschemeyer, and Theda Skocpol (eds.), Bringing the State Back In, Cambridge University Press, 1985, 170-171.

115. The reciprocal relationship between print media and the Japanese public is a central theme in Huffman’s, Creating a Public. Japanese scholars like Torigoe, Ueda, and Hasegawa, tend to shy away from the idea of print media as a collection of agents. When asking whether men like Iwaya, Oshikawa, or Miyazaki were militarists, for example, they evade the hard answer, opting for the simpler, less pointed one that these men were products of their times.

116. Karl Marx, The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napoleon, Kessinger Publishing, 2001, 3-4.

117. Helen Mears, Mirror For Americans: