The Failure of Imagination: From Pearl Harbor to 9-11, Afghanistan and Iraq

John W. Dower with an introduction by Laura Hein

Introduction

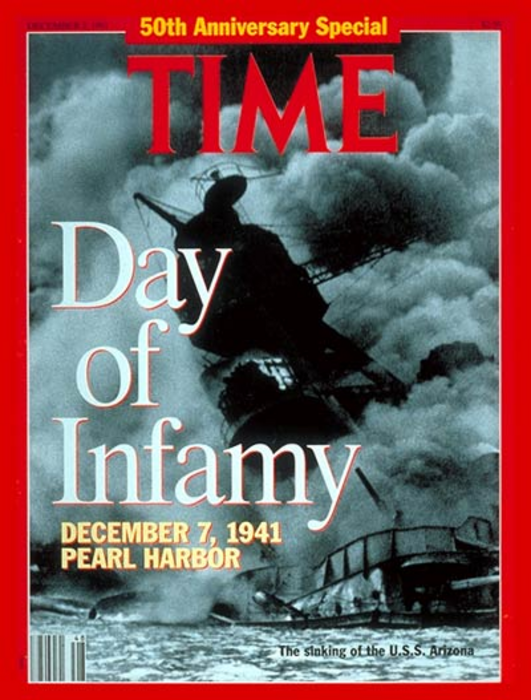

The Asia Pacific Journal is proud to offer its readers a preview of John W. Dower’s new book, Cultures of War: Pearl Harbor/ Hiroshima/ 9-11/ Iraq (New York: Norton 2010). In the first days after the Al Qaeda attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon on September 11, 2001, prominent American news sources reacted by invoking the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, and President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s description of the event as an act of “infamy.” That analogy caught the attention of many people, but Dower has thought more deeply than most about the underlying issues. The resonances between the past and the present are profound and disturbing.

Dower attends to what people do and also how they justify their actions, because he wants to know why smart people—and smart societies—do such stupid things. More precisely, he is interested in why they do the same stupid things over and over again, often with such malevolent consequences. His conclusions about the cultures of war do not bode well for the future. This excerpt focuses on why the United States government was unprepared for the attacks in 1941 and again in 2001 and, to a lesser extent, on the reasoning of both sets of attackers. The “failure of imagination” he analyzes was systemic, involving the failure to accurately perceive either the potential enemy or ourselves, regardless of the “we” in question. When it comes to war, no one seems to get it right.

Dower is particularly good at registering when his subjects are judging other societies by standards other than those reserved for themselves and teasing out the consequences of those assumptions. Some of that dissonance is racial contempt, the subject that he earlier pioneered in War Without Mercy: Race and Power in the Pacific War (New York: Pantheon Books, 1986). Readers familiar with that book will not be surprised by the dismissive language with which Americans proclaimed their natural superiority over Japanese—or the extent to which the Japanese sense of privilege based on racial pride mirrored the American one. People were franker about their racial views in the 1940s than today but, alas, Dower had no trouble finding recent assessments that emphasized similar contempt for “people with towels on their heads” and “Arabs wearing robes.” Yet, racism, although impossible to ignore, is not the precise center of the problem. That honor goes to the arrogance of thinking of one’s own society as superior because it is richer or more influential, not just on racial grounds. This smugness explains why Americans simply could not imagine the possibility of effective attacks by either the Japanese or Al Qaeda, even though, as Dower documents, ample evidence existed of not only enemy intentions but also enemy capabilities. Even more disturbingly, as he gently concludes here, on both occasions the shock of the attacks caused Americans to jump directly from under-estimating Japanese/Al Qaeda military capability to wild anxiety about “an omnipotent, unslayable hydra of destruction,” as the 9-11 Commission put it.

Dower asks what happens when Americans judge Japan or Al Qaeda by the same standards as we do the United States, and the freshness of his conclusions reveals how rarely this exercise is conducted. As he explains here, the Japanese decision to attack the United States in 1941 was a “war of choice,” dressed up as a war of necessity, in terms very like those used sixty years later by American government leaders explaining the attack on Iraq. Both decisions were based on some spectacularly wrongheaded assumptions, woven into a rationale that in other respects was logical and informed. So, for example, once Japanese leaders decided that controlling large portions of the Asian mainland was vital to national security, it became very hard not to widen the war in 1941 when faced with strong US pressures to contain their expansion. Americans likewise ignored all the lessons of the failed Soviet attempt to control Afghanistan as well as the advice of nearly all experts on Iraq. And, as the combatants in many conflicts have discovered, after the fighting has started and people have died, it is politically and psychologically easier to continue a war than to end it on any terms other than complete victory.

Refusing to treat foreigners as rational and morally recognizable human beings also blinds us to the unintended consequences of our own actions. Dower describes here how the Hearst newspaper chain congratulated itself in 1945 for having warned its readers steadily from the 1890s that Japan was dangerous. Readers of Dower’s earlier work will also recognize one of his key themes, muted in this excerpt: that, although these newsmen were writing for an American audience, Japanese people, including government officials, also read the editorials. In other words, the hostility of the Hearst papers certainly contributed to the Japanese belief that war with the United States was inevitable. The controversy erupting in August 2010 over whether a planned Islamic cultural center would defile the “sacred ground” of lower Manhattan seems likely to have similar consequences. Many of the Americans commenting on this plan seem unaware, let alone concerned, that their characterization of Islam itself as an enemy force confirms Al Qaeda’s view of the world. Indeed, acknowledging such audiences, and the legitimacy of any of their concerns, is too often treated as unpatriotic in the context of a culture of war.

In his 1999 book, Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II, (New York: Norton and the New Press) Dower explored the vast (and sometimes unintentionally hilarious) gap between American rhetoric and its actual behavior during the postwar occupation of Japan. Strikingly, most of the Americans involved remained oblivious to the contradictions, even though they were blindingly obvious to outside observers. The ease with which they ignored their own behavior rivaled Japanese wartime self-deception about their efforts to rescue Asia from Western imperialism. Both nations insisted that they be judged by their ideals rather than by their actions. No doubt Iraqi strongman Saddam Hussein did the same.

Perhaps most disturbingly, but also admirably, Dower challenges the idea that striving to put intelligent and ethical people in power is enough. He has a great eye for quirky individuals and diverse personalities, both decision makers and clever observers. Their biggest mistakes are honest ones, although secrecy, propaganda, and cynicism all play supporting roles. Rather than evil villains, the officials highlighted here are smart, usually sincere, and deeply, deeply flawed. Yet, although individuals do make a difference in Dower’s mental world, his message is that lack of respect for far-away people and absence of humility about our own behavior is embedded in institutions as well. Unless we change both the attitudes and the institutions that nurture our cultures of war, we are doomed to repeat our costly mistakes forever. LH

“Little yellow sons-of-bitches”

In all the many volumes of documents, testimony, and commentary about the intelligence failure of 1941, there are no more telling words than an informal confession made by Admiral Kimmel while the congressional hearings of 1945–46 were taking place.

Although the commanders in Pearl Harbor had received a “war warning” message from Washington on November 27, ten days before the attack, when the first wave of Japanese planes swept in, General Short was caught with his air force tightly bunched on the ground, most of his ammunition locked away, and major airfields such as Hickam without any antiaircraft guns. Admiral Kimmel’s Pacific Fleet (except the carriers, which by sheer good fortune had put out for maneuvers) was peacefully at anchor in the harbor. These were the shocking failures that led the first post–Pearl Harbor investigation to charge the two officers with dereliction of duty, later tempered in the findings of the congressional inquiry to grave errors of judgment.

|

Japanese crew cheers torpedo plane taking off from the Shokaku, one of six aircraft carriers in the attack force |

Both Short (who died in 1949) and Kimmel (who passed away in 1968, at eighty-six) argued that Washington failed to share all the information about Japanese plans it had gleaned through the still-secret Magic code-breaking operation. Never, they claimed, were they explicitly instructed to prepare for an actual attack. The two officers were given the opportunity to defend themselves in the postwar hearings, where Short read a 61-page typed statement and Kimmel’s prepared statement ran to 108 pages. The disgraced admiral’s most cryptic and persuasive explanation of why he had been caught by surprise, however, came in a lunch-break conversation with Edward Morgan, a lawyer who eventually drafted the majority report. As Morgan recalled it years later, the exchange went as follows:

Morgan: Why, after you received this ‘war warning’ message of November 27, did you leave the Fleet in Pearl Harbor?

Kimmel: All right, Morgan—I’ll give you your answer. I never thought those little yellow sons-of-bitches could pull off such an attack, so far from Japan.1

Although unvarnished language like this did not make it into the transcript of the hearings, the majority report did take care to argue that “had greater imagination and a keener awareness of the significance of intelligence existed . . . it is proper to suggest that someone should have concluded that Pearl Harbor was a likely point of Japanese attack.” Failing to think outside the box is a theme that surfaces and resurfaces in the serious general literature. Gordon Prange, for example, speaks of “psychological unpreparedness”; Roberta Wohlstetter, of “the very human tendency to pay attention to the signals that support current expectations about enemy behavior.”2

Admiral Yamamoto, like his American navy counterpart, also put the American failure in plain language—in his case, in two personal letters written shortly after the attack. On December 19, he wrote this to a fellow admiral:

Such good luck, together with negligence on the part of the arrogant enemy, enabled us to launch a successful surprise attack.3

|

Japanese attack planes taking off Japanese aerial photograph of the first torpedo bombs hitting U.S. warships on Battleship Row |

Two days later, writing to the student son of a personal friend, Yamamoto made a bit clearer what he had in mind in speaking of American arrogance. This letter, in its entirety, read as follows:

22 December 1941

My dear Yoshiki Takamura,

Thank you for your letter. That we could defeat the enemy at the outbreak of the war was because they were unguarded and also they made light of us. “Danger comes soonest when it is despised” and “don’t despise a small enemy” are really important matters. I think they can be applied not only to wars but to routine matters.

I hope you study hard, taking good care of yourself.

Good-bye,

Isoroku Yamamoto4

Yamamoto obviously misread American psychology disastrously when expressing hope that the surprise attack would strike a crippling blow at morale. The Americans, however, also disastrously misread and underestimated the Japanese. Can there be a more precise confirmation of Yamamoto’s perception of Japan being “despised” and made light of as a “small enemy” than Kimmel’s frank reference to “those little yellow sons-of-bitches”?

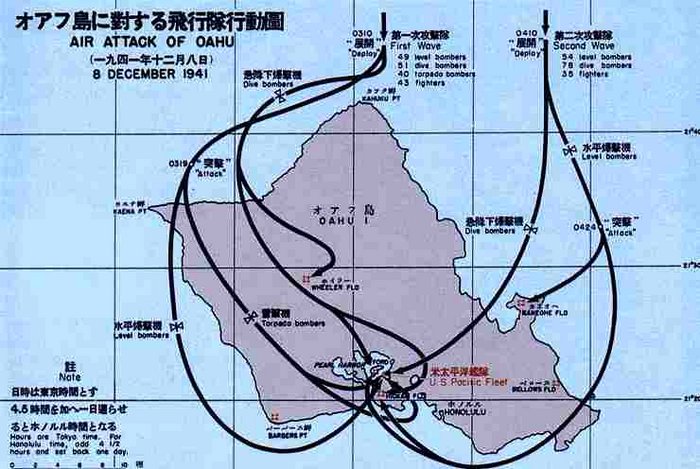

Japanese map of the Pearl Harbor attack

In a rational world, this should not have been the case. American perceptions of Japan as a potential foe traced back to the turn of the century, when Japan startled the world by defeating China and Tsarist Russia in quick succession (in the Sino-Japanese War of 1894–95 and Russo-Japanese War of 1904–5), thereby joining the Western, Caucasian, and Christian expansionist nations as one of the world’s few imperialist powers. Financiers in New York and London had helped finance the Russo-Japanese War, and many Western observers expressed admiration for the doughty “Yankees (or Brits) of the Pacific,” but such support and praise were hardly unalloyed. The obverse side of support and respect for Japan and its spectacular accomplishments in “Westernization” was fear of the “Yellow Peril”—fear, that is, that Asia’s masses would acquire the scientific skills and war-making machinery hitherto monopolized by the West.5

From the 1890s to the eve of Pearl Harbor, influential U.S. media such as the Hearst newspapers relentlessly editorialized that Japan posed a direct threat to the United States. Concurrent with Japan’s formal surrender in September 1945, the Hearst syndicate ran a two-page advertisement in Business Week proudly itemizing how “for more than 50 years, the Hearst Newspapers kept warning America about JAPAN.” The spread reproduced “a startling prophetic cartoon” from 1905 depicting a Japanese soldier standing in Korea with the sun behind him and his shadow falling across the Pacific onto the west coast of the United States. It boasted about how “the Hearst Newspapers first pointed out the ‘Yellow Peril’ of Japan to U.S. aims and interests in the Pacific” in the 1890s; how in 1898 it had “urged the annexation of the Hawaiian Islands by the United States as a defense measure against growing Japanese power in the Pacific”; how in 1912 the paper had “focused national attention on Japanese attempts to colonize Lower California”; and on, and on, up to 1941, when “the Hearst Newspapers, right up to the time that bombs fell on Pearl Harbor, were still hammering for increased naval appropriations and for strengthened fortifications in the Pacific.”6

Here, it would seem, was imagination and “psychological preparedness” in abundance; and the United States did, in fact, adopt strategic policies that took the rise of Japan into consideration. Hawaii was annexed in 1898, and from 1905 Navy planners identified Japan as the major hypothetical enemy in the Pacific; there was, of course, no other candidate. In the color-coded contingency plans the Navy introduced before World War I, war plans vis-à-vis Japan were coded “Orange.” It has been calculated that, over ensuing decades, officers at the Naval War College tested and refined the Orange plan at least 127 -times.7

In May 1940, the clarity of Japan’s intent to advance into Southeast Asia and the South Pacific led to transfer of the U.S. Pacific Fleet from the west coast of the United States to Hawaii, as a more visible “deterrent.” Several months prior to the Pearl Harbor attack, this ostensible deterrent was augmented by carefully leaked plans to strengthen U.S. forces in the Philippines with advanced B-17 “Flying Fortress” bombers. (In October 1941, Secretary of War Stimson expressed hope that the threat of these bombers would suffice to keep Japan from going after Singapore “and perhaps, if we are in good luck, to shake the Japanese out of the Axis.”) Three times in 1941—in June, July, and October—the army and navy in Hawaii were placed on alert during particularly tense moments in the deteriorating relationship between the two -countries.8

Beyond this deep history of mistrust and fear, it might have been expected that the plain nuts-and-bolts of military developments—the huge buildup of warships, aircraft, and ground forces that took place in the years preceding Pearl Harbor—would have made it apparent that Japan would be a formidable foe. This was not the case, and as a consequence it was more than just the unexpected attack that shocked Americans. Even more unnerving was the competence of the Japanese military.

This, at least, should not have come as a surprise. Japan had been working toward a capability for waging “total war” since the early 1930s. (Such thinking dated back to lessons drawn from World War I, which stimulated military strategists everywhere to consider how to mobilize the total resources of the nation in the eventuality of another great war.)9 Isolation from the world community after the takeover of Manchuria in 1931 accelerated these plans, and from 1932 on the military establishment dominated the Japanese government. The nation had been at war with China for over four years at the time Pearl Harbor was attacked; and while the interminable nature of this conflict could be taken as a sign of military shortcomings and overextension, the other side of the coin was that the China war had created an experienced fighting force and spurred major advances in military technology.

These developments were not hidden, but even the experts failed to see them clearly—or, at least, to see them whole. Thus, the list of Japan’s military capabilities that caught the Americans by surprise seems quite astounding in retrospect. Their torpedoes were more advanced than those of the Americans. (It was last-minute development of an airplane-launched torpedo with fins, capable of running shallow, that made the Pearl Harbor attack so deadly.) Their sonar, which the Americans believed inferior, was four to five times more powerful than what the U.S. military had at the time. Although the high-speed Mitsubishi “Zero,” introduced to combat in China in August 1940, was more effective than any U.S. fighter plane at the time, the Americans underestimated its range, speed, and maneuverability.

The list goes on. According to testimony introduced at the congressional hearings, the Japanese had “better material in critical areas such as flashless powder, warhead explosives, and optical equipment.” Japan’s monthly output of military aircraft by December 1941 was more than double what the Americans estimated it to be. Their pilots, intensively trained and also seasoned by combat in China, were among the best in the world. As noted in an authoritative history of the U.S. air forces in World War II, “the average pilot in the carrier groups which were destined to begin hostilities against the United States had over 800 hours” of flying experience. The “first-line strength” of the imperial air forces “gave them a commanding position in the Pacific.”10

In Prange’s emphatic estimation, on December 7, 1941, “Japan stood head and shoulders above any other nation in naval airpower.” The British military historian H. P. Willmott concludes that “in December 1941 the Imperial Japanese Navy possessed clear superiority of numbers in every type of fleet unit over the US Pacific and Asiatic fleets”; that it had “superiority over its intended prey” in the crucial category of aircraft carriers; and that in tactical technique, it was “second to none” at the opening stage of the war. Willmott also observes that the land-based Betty medium bomber developed by the Japanese in the 1930s “possessed a range and speed superior to any other medium bomber in service anywhere in the world.” Other sources call attention to the Imperial Navy’s exceptional skill in night gunnery, and its initial advantage in launching torpedoes from cruisers. As the audacious December 7 attack made painfully obvious, the ability of Japan’s naval officers to plan and execute an exceedingly bold and complex operation—particularly one involving carriers—was simply beyond imagining. Except, of course, that the Japanese had imagined it down to the last detail.11

What accounts for this American failure of imagination?

Racism is part of the answer, but only part. The Japanese were not merely “sons-of-bitches.” They were “little,” and they were “yellow.” In the American vernacular, the phrase “little yellow men” had become so common that it almost seemed to be a single word. To be “yellow” was to be alien as well as threatening (as in the “Yellow Peril”); but the reflexive adjective “little” was just as pejorative, for it connoted not merely people of generally shorter physical stature, but more broadly a race and culture inherently small in capability and in the accomplishments esteemed in the white Euro-American world.

Such contempt was not peculiar to Americans. It was integral to the conceit of a “white man’s burden” and sneering animus of white supremacy that invariably accompanied Western expansion into Asia. When, after Pearl Harbor, the Japanese swept in and conquered their supposedly impregnable outpost in Singapore, the British also expressed disbelief (and engaged in the same sort of racial invective). Wherever and whenever objectivity overrides prejudice, it is usually the exception that proves the rule.12

Still, racial blinders alone do not adequately account for the failure to anticipate Pearl Harbor. The Americans also were unable to imagine what it was like to look at the world from Tokyo. From the Japanese perspective, the entire globe was in turbulent flux and grave crisis. The nation’s situation was desperate. Its cause was just. And things had come to such a pass that there was no alternative but to take whatever risk might be necessary.13

Rationality, Desperation, and -Risk

The top-secret policy meetings that took place at the highest level in Japan from the spring of 1941, including “Imperial Conferences” at which diplomatic and military decisions were approved by the emperor, are provocative in retrospect because of the generic, rather than uniquely Japanese, outlook they reveal. It was unthinkable for the nation’s leaders to question the assumption that China, including Manchuria, was Japan’s economic lifeline, or that the war there was not merely essential to national survival but also moral and just. Indeed, with Japan having already “sacrificed hundreds of thousands of men” in invading and occupying China, it was all the more inconceivable to consider military withdrawal from the continent as the United States had demanded in pre–Pearl Harbor negotiations. It also was taken for granted that the nation could not break the military stalemate in China without access to the strategic resources of Southeast Asia, and time was running out. “Our Empire’s national power,” explained the head of the Planning Board at one critical meeting, “is declining day by day.” The argument that creation of a “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere” would ensure not only the “security and preservation of the nation” and well-being of all Asia, but ultimately “world peace,” went unchallenged.14

This was not propaganda intended for domestic or international consumption. It was what these men believed—the assumptions and emotions that guided their deliberations and decisions. And so, in the end, the policy makers agreed there was no choice but to break off relations with the United States and “move South.” To give in to U.S. demands would be “national suicide.” “I fear,” Prime Minister Tōjō stated at a critical meeting in early November, “that we would become a third-class nation after two or three years if we just sat tight.”15

The fateful decision to secure their nation’s position in Asia by pursuing a war of choice against the United States and other Allied powers was reinforced by a number of seemingly sane and rational projections. These included German victory in Europe, particularly against England and the Soviet Union; U.S. difficulties in fighting a two-front war; the strength of isolationist sentiment in the United States, and consequently probable domestic opposition to a protracted war in the Pacific; and the fact that there was a current of thinking in U.S. ruling circles, exemplified by Joseph Grew, that saw a constructive role for Japan as a “stabilizing force” against “chaos and communism” in China. Additionally, it was argued that while Japan lacked the industrial potential of the United States, its army and navy were huge; its forces, including air forces, were seasoned by combat in China; and the esprit de corps of the emperor’s loyal soldiers and sailors was superior to whatever fighting spirit the Americans could hope to marshal. (In a casual conversation a few months after arriving in defeated Japan, General MacArthur told a British diplomat he “would have given his eyeballs to have such men” as the Japanese forces he encountered in the Philippines.) Given such considerations, it did not seem unreasonable to hope that the war would end in some sort of negotiated settlement with the United States, with both sides cooperating in maintaining peace in Asia.16

Counterfactual rumination (the “what if” school of history) also helps illuminate the misplaced optimism of Japan’s war planners. That Japan was able to drag out the war for over three and a half years after Pearl Harbor was due in considerable part to the priority the United States gave to the European theater. At the same time, with a little more luck and operational shrewdness Japan might have prolonged the war even longer. For example, what if: (1) Germany had not attacked the Soviet Union while the Japanese were descending their slippery slope to war, thus leaving resistance to U.S. and British forces stronger on the European front; (2) the U.S. carriers had been berthed at Pearl Harbor at the time of the attack, and had not been by sheer chance at sea; (3) the Pearl Harbor attack force had launched a third wave of strikes and destroyed repair facilities and critical fuel sources; (4) the Japanese had changed their military code in 1942, thus thwarting major post–Pearl Harbor U.S. breakthroughs in cryptanalysis that proved critical not only in decisive battles such as Midway but also in the ongoing decimation of Japanese warships and merchant vessels by American submarines; (5) Japanese naval commanders had been less timid at decisive battles such as Midway and the Solomons? (The counterfactual question that trumps all others is what if Japan had excluded Pearl Harbor and the Philippines from the December 1941 offensive? This would have eliminated the “Remember Pearl Harbor” rage that solidified the nation behind retaliation, and forced the Roosevelt administration to decide whether or not to declare war in the face of continuing isolationist opposition.)

There is almost no end to the “what ifs” of history, and perhaps military history in particular. (Hitler’s folly in deciding to attack the Soviet Union is the great strategic what if where the war in the West is concerned.) Be that as it may, Japan’s desperation and consequent willingness to take extreme risks also enter the strategic equation. It was irrational to miscalculate the psychological impact the Pearl Harbor attack would have among Americans, and hope instead that demoralization would be the result. By the same measure, however, the U.S. leadership was grievously negligent in ignoring the possibility of direct attack once it became clear the Japanese had concluded they could not retreat in China and, unless the Western powers lifted their embargoes on strategic exports, had no alternative but to move into Southeast Asia.

Military men, like politicians, cherish cherry-picked history and the symbolism and rhetoric of past challenges and glories. When MacArthur took the Japanese surrender on the Missouri in September 1945, the flag raised at Morning Colors was the same Stars and Stripes that had flown over the Capitol in Washington on December 7, 1941, while the bulkhead overlooking the ceremony displayed the thirty-one-star flag Commodore Matthew Perry had flown on his flagship in 1853, when he initiated the gunboat diplomacy that forced Japan to abandon its feudal seclusion. In the surprise attack of December 7, the Japanese engaged in similar symbolism. As the attack force approached Pearl Harbor, the flagship Akagi ran up the “Z” flag signal that had been hoisted more than thirty-five years earlier by Admiral Heihachirō Tōgō in the decisive 1905 Battle of Tsushima, in which Tōgō’s modern warships destroyed a huge Russian armada that had sailed all the way from the Baltic, thereby assuring Japan’s emergence as a great power. The signal read, “The rise and fall of the Empire depends upon this battle; everyone will do his duty with utmost efforts.”

Shortly before this, the commander of the Pearl Harbor attack fleet read an “imperial rescript” to his men that had been prepared earlier by the emperor. “The responsibility assigned to the Combined Fleet is so grave that the rise and fall of the Empire depends upon what it is going to accomplish,” the message said. Japan’s sovereign placed his trust in the fleet to accomplish what it had long been training for, “thus destroying the enemy and demonstrating its brilliant deed throughout the whole world.”17

One side’s infamy was the other’s brilliant deed, on which the very fate of the empire depended.

Aiding and Abetting the Enemy

Al Qaeda commanded no military machine on September 11. It had been engaged in no negotiations with the United States, nor could it have been, not being a nation-state. Although Osama bin Laden’s ambitions had grown ever more expansive over the years since Al Qaeda’s founding in 1988, and although U.S. intelligence specialists took seriously his vision of a “great Caliphate,” he was not engaged in an escalating quest for autarky—for military and economic domination of a formal, secure, and self-sufficient sphere of influence—comparable to the quest that had obsessed Japan ever since its takeover of Manchuria in 1931.18

Even here, however, certain points of comparison merit attention. A full decade of mounting tensions preceded Pearl Harbor, beginning with the impasse over Manchuria. In the case of Islamist terrorism, the first attack in the United States took place in 1993, when the World Trade Center suffered extensive damage from explosives detonated in a parked van. Although later intelligence connected this to Al Qaeda, this was not clear for a number of years. A National Intelligence Estimate distributed in July 1995 predicted future terrorist attacks against and in the United States, but the 9-11 Commission concluded that Al Qaeda itself was not identified in a conspicuous manner until around 1999—three years after the NSC’s Richard Clarke dates this “discovery,” eleven years after the organization was founded, six years after the first attack on the World Trade Center, and only two years before the September 11 attack.19

Where the actual attack plans for 1941 and 2001 are concerned, both were quite long in the hatching. The Pearl Harbor operation was conceived by Admiral Yamamoto at the end of 1940, probably in December, and the first draft of an operational plan was drawn up the following March (by Commander Minoru Genda and Rear Admiral Takijirō Ōnishi, who in late 1944 would become the prime mover behind the kamikaze attacks). By April, the project had been moved into command channels, and training in activities such as aerial torpedo practice commenced in May and June. War games for the entire “Southern Operation,” including Hawaii, were carried out in Tokyo over a ten-day period beginning September 11.

The “Operation Hawaii” plan was accepted in principle by the navy chief of staff in mid-October, and Emperor Hirohito was briefed on this at the imperial palace some time between October 20 and 25. “Dress rehearsals” by the fleet began in October, and the plan received final approval by the navy general staff in early November. On November 17, vessels assigned to the attack force began making their way to Hitokappu Bay in the Kurile Islands (under Japanese control since the Russo-Japanese War), from where—on November 25 (November 26, Japan time)—the fleet would depart for the attack. In Al Qaeda’s case, where there is less information, the 9-11 Commission simply concluded that the complex September 11 operation was “the product of years of planning.”20

It is also provocative to note that collusion or at least mixed signals between the American side and the enemy preceded both catastrophic surprise attacks. In U.S.–Japanese relations, this took several forms. Despite the fact that the 1937 invasion and occupation of China provoked fairly widespread sympathy for China and condemnation of Japan in the United States, until around mid-1940 pressures to appease Japan came from many directions. For all practical purposes, isolationists associated with “Fortress America” and “America First” activities often found themselves on the same page with peace and antiwar groups. Both desired that the United States isolate itself from foreign conflicts and avoid provoking Japan in any way that might lead to hostilities. As late as October 1941, one informal council devoted to “prevention of war” that included several well-known scholars of Far Eastern relations was still urging the government to “make a deal” with Japan. At both official and public levels, attention focused far more on Europe than on Asia, particularly after Germany unleashed its blitzkrieg in 1939; to some degree, this fixation on the war in Europe strengthened popular opposition to any involvement in the conflict in Asia.21

Japanese leaders, naturally attentive to such sentiments, found them in more explicitly governmental circles as well, where officials like Ambassador Grew were cautiously receptive to the argument that Japan could be a bulwark against both domestic chaos in China and Soviet-led international communism. Although Grew became increasingly critical of Japan’s actions beginning in mid-1940, as late as September 1941 he was still urging “constructive conciliation.”22

Just as encouraging, if not more so, was the attitude within U.S. business circles. The dollar value of U.S. exports to Japan in 1937 was more than five times that of the export trade with China, and in 1940 still amounted to roughly three times the China trade. A major portion of these exports consisted of strategic materials such as aviation fuel, crude and refined oil, scrap iron, and steel—all critical to the Japanese war machine. A fair indication of sentiment in the business community emerged in a survey published in Fortune magazine in September 1940, allegedly tapping the views of some “15,000 businessmen” including directors of the 750 largest American corporations. Forty percent of respondents chose to “appease” the Japanese, and another 35 percent to “let nature take its course.”23

The United States did not begin to impose serious controls over exports until mid-1940, when Japan, following the fall of France to the Nazis, moved troops into the northern half of French Indochina and began the courtship that would culminate in the Axis alliance in September. Part of the U.S. concern involved old-fashioned colonial interests—namely, fear that losing Southeast Asia would deprive Britain of critical resources. The scenario that unfolded thereafter became an all-too-familiar tit-for-tat game: the more the U.S. government tightened economic screws to deter Japanese aggression, the more persuaded Japanese leaders became that their empire faced disaster and there was no alternative but to “move South.”

Although there was no comparable economic dimension in the rise of Islamist terrorism, there was an analogous prehistory of support and appeasement prior to September 11. In the closing decade of the Cold War, U.S. strategic planners embraced the prospect of an anticommunist “arc of Islam” stretching east from the Middle East along the underbelly of the atheistic Soviet Union. The policy birthed by such thinking took the form of covert collaboration with Pakistan and Saudi Arabia in recruiting, training, and arming radical mujahideen for the war against Soviet forces in Afghanistan between 1979 and 1989. President Ronald Reagan posed for a photograph with mujahideen leaders in the White House in 1986, and at one point CIA director William Casey, a devout Catholic, sponsored a translation of the Qur’an for dissemination to Uzbek-speaking holy warriors. More striking is the weaponry provided to these anti-Soviet zealots by true believers in Washington who were persuaded that a shared monotheism made Christians and radical Islamists kindred souls. As itemized by Steve Coll, these weapons included “antiaircraft missiles, long-range sniper rifles, night-vision goggles, delayed timing devices for plastic explosives, and electronic intercept equipment.” Also part of this covert support were Japanese-made pickup trucks, Chinese and Egyptian rockets, Milan antitank missiles, and somewhere between 2,000 and 2,500 heat-seeking Stinger missiles. Although material U.S. aid was directed primarily to the Afghan resistance forces rather than volunteer Arab fighters (like bin Laden), the U.S. government looked favorably on the latter.24

Benazir Bhutto, the Pakistani political leader assassinated in 2008, dwelled on this shortsighted Realpolitik in a book completed only days before her death. In her view, the blowback from covert engagement in the anti-Soviet Afghanistan war (which involved close U.S. collaboration with Bhutto’s political adversaries in Pakistan) was by no means an exceptional instance of myopic Western policies in the Middle East. On the contrary, the United States and European powers had a long history of engaging in “double standards” by preaching freedom and development while in actual practice supporting both dictators and, in Afghanistan, the most radical and oppressive Islamist fundamentalists. Over the course of decades, she concluded, the West had “unintentionally created its own Frankenstein’s monster.” These were harsh words and more than a little disingenuous, since while she was prime minister of Pakistan from 1993 to 1996, her own government—alarmed by the civil strife that followed the Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan in 1989—had provided covert financial support, supplies, and military advisers to the extremist Taliban who later provided a haven for bin Laden.25

Monsters commonly have multiple creators, but this does not diminish the U.S. role in helping to promote Islamist radicalism early on. Like the Japanese soldiers and sailors who became seasoned veterans in the war against China and initially benefitted materially from U.S. support through trade in strategic goods, the mujahideen—once proxy soldiers for the U.S. government and romanticized “freedom fighters” in Washington and the U.S. media—emerged from Afghanistan as hardened fighters primed for new missions. It fell to Al Qaeda, birthed in Afghanistan in 1988, to define that mission for them.

“This little terrorist in Afghanistan”

The stunning “asymmetrical” victory of Afghan and Muslim fighters over the Soviet Union emboldened Islamist radicals to believe they could prevail over U.S. military power as well. In a television interview more than three years before 9-11, bin Laden boasted that the victory of lightly armed holy warriors in Afghanistan “utterly annihilated the myth of the so-called superpowers.” (This interview was rebroadcast on Al Jazeera nine days after 9-11.) By contrast, U.S. policy makers drew few if any counterpart lessons. With the collapse of the Soviet Union, the politicized zealotry they had encouraged in Afghanistan no longer attracted top-level attention. Even within the U.S. military, the effectiveness of Islamist insurgency and terror did not prompt serious attention to counterinsurgency doctrine.26

This was true when the Soviet Union withdrew its humiliated forces from Afghanistan in 1989 and official Washington proceeded to remove the latter nation from its radar. It was still true in 2001, when the United States invaded Afghanistan and routed the Taliban in the wake of the 9-11 attacks. And, despite belated attention to counterinsurgency tactics in Iraq beginning around 2006, it would remain largely true where Afghanistan was concerned to the end of the Bush presidency, when the Taliban were on the upsurge and again helping shelter bin Laden. At the beginning of 2009, as a new administration assumed power in Washington, Russia’s ambassador to NATO looked back on the twentieth anniversary of the Soviet withdrawal and held this up as a mirror to the beleaguered U.S. military mission in Afghanistan. “They have repeated all our mistakes,” he observed, “and they have made a mountain of their own.”27

Why did top military and civilian leaders fail to take asymmetrical threats from Al Qaeda and the Islamists seriously? As with the earlier failure to take Japanese military capabilities seriously, part of the answer lies in racial arrogance and cultural condescension. When Charles Freeman, the U.S. ambassador to Saudi Arabia at the time of the first Gulf War in 1991, tried to draw attention to the mujahideen after the Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan, for example, he found no one interested, including top leaders at the CIA. “Part of the attitude in Washington,” he recalled, “was, ‘Why should we go out there and talk to people with towels on their heads?’”28

Michael Scheuer, who headed the CIA’s “bin Laden unit” until being cashiered in 1999, tells a similar story in even grittier language. Washington’s top personnel and policy makers, he declared, are “so full of themselves, they think America is invulnerable; cannot imagine the rest of the world does not want to be like us; and believe an American empire in the twenty-first century not only is our destiny, but our duty to mankind, especially to the unwashed, unlettered, undemocratic, unwhite, unshaved, and antifeminist Muslim masses.” One could only describe this hubris as “arrogance (or is it racism?),” Scheuer went on. The elites simply could not fathom that “a polyglot bunch of Arabs wearing robes, sporting scraggly beards, and squatting around campfires in Afghan deserts and mountains could pose a mortal threat to the United States.”29

This was the “little yellow men” mindset transferred to the Middle East. As in 1941, civilian and military planners underestimated the enemy and failed to grasp both the depth of their self-righteousness and their willingness to take enormous risk as well as heavy losses. Most disastrously, they were unable to imagine this enemy possessing the cunning and competence to pull off a complex and imaginative act of aggression. None of his peers challenged Deputy Secretary of Defense Wolfowitz when, five months before 9-11, he dismissed bin Laden as “this little terrorist in Afghanistan.”

Once again, as with system breakdown and leadership negligence, the diagnostic language in postmortems of the failure of imagination exposed on September 11 is essentially the same as that which analysts have long used in describing the disbelief that greeted Pearl Harbor: psychological unpreparedness, prejudices and preconceptions, gross underestimation of intentions and capabilities. There is a sense of encountering a pathologist’s repetitive case book, glossing near-identical cases. Thus, to crib from Roberta Wohlstetter: prior to September 11, American analysts (with some marginalized exceptions) and decision makers simply were unable “to project the daring and ingenuity of the enemy.” To borrow from Admiral Yamamoto’s letter to a young student: Bush administration planners were undone by the arrogance of despising a small enemy. To appropriate Admiral Kimmel’s pithy words: no one in a position of command thought that those little Muslim sons-of-bitches could pull off such a spectacular attack, so far from home.

|

World Trade Center on September 11, 2001 |

In this ethnocentric world, terrorists of the twenty-first century were “little men” in a compound sense—little because they were racially, ethnically, culturally, and religiously alien; and little because, unlike Japan sixty years earlier, and unlike the Soviet Union or China or even Iraq, Iran, and North Korea, they were not a nation-state. When Richard Clarke criticized the Bush administration’s disregard of the Al Qaeda threat, and its subsequent misguided response to September 11, his most vivid revelations concerned the immediate response—and disbelief—of the president’s inner circle of advisers:

On the morning of the 12th, DOD’s [the Department of Defense’s] focus was already beginning to shift from al Qaeda. CIA was explicit now that al Qaeda was guilty of the attacks, but Paul Wolfowitz, Rumsfeld’s deputy, was not persuaded. It was too sophisticated and complicated an operation, he said, for a terrorist group to have pulled off by itself, without a state sponsor—Iraq must have been helping -them.

On the same day, September 12, Clarke went on to record, President Bush “grabbed a few” intelligence experts including himself: “‘Look,’ he told us, ‘I know you have a lot to do and all . . . but I want you, as soon as you can, to go back over everything, everything. See if Saddam did this. See if he’s linked in any way.’”30

These responses, revealed after the invasion of Iraq, can be interpreted as genuine or Machiavellian (already preparing to use the 9-11 outrage to initiate a long-desired war against Iraq)—but in all likelihood they were both. Ensuing use of the “war on terror” to invade Iraq, with all the distortion of intelligence data this involved, was duplicitous; but the prior failure to take Al Qaeda or the terrorist threat really seriously reflected a lingering Cold War mindset. The 9-11 Commission singled out “imagination” as one of “four kinds of failures” revealed by the attacks of September 11. (The other three were “policy, capabilities, and management.”) The commission even went so far as to recommend remedying this by “institutionalizing imagination”—an oxymoron one could easily imagine the bureaucratic behemoth taking seriously to heart by forming committees, preparing flow charts, and perhaps even creating a supersecret NIA (National Imagination Agency).31

|

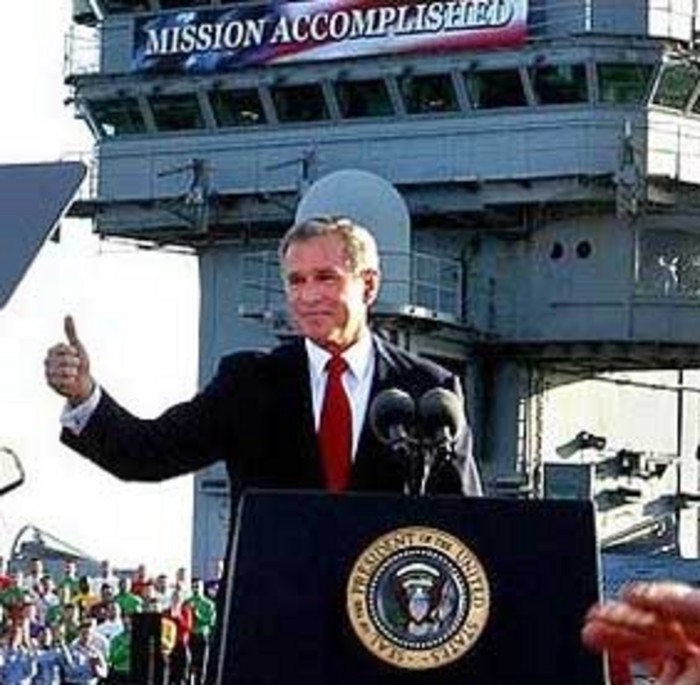

President Bush proclaims “Mission Accomplished aboard the USS Lincoln on May 1, 2003 following US invasion of Iraq |

In a passing comment, the 9-11 Commission also took note of what happens when, after unexpected catastrophe, erstwhile little men prove to be formidable adversaries:

Al Qaeda and its affiliates are popularly described as being all over the world, adaptable, resilient, needing little higher-level organization, and capable of anything. The American people are thus given the picture of an omnipotent, unslayable hydra of destruction. This image lowers expectations for government effectiveness.

What the commission was evoking was what one U.S. counterterrorism official called “the superman scenario.” The shocking success of the little Muslim men abruptly endowed them with hitherto undreamed-of powers and capabilities—to the extent of precipitating a declaration of a global war on . . . what? On a tactic (terror). On a worst-case scenario where Al Qaeda or other terrorists might obtain weapons of mass destruction. Eventually, this paranoia reached such a level that deflating hyperbole became almost a category in itself in the burgeoning popular literature on terrorism. As another counterterrorism expert put it, writing specifically about Al Qaeda, “by failing to understand the context of the organization, its very strengths and weaknesses, we magnified our mental image of terrorists as bogeymen.” Yet another posed the rhetorical question “Are they ten feet tall?” and deemed it necessary to answer this. “They’re not,” he assured his audience.32

A comparable cognitive dissonance took place after Pearl Harbor. In American eyes, the Japanese foe morphed, overnight, from little men into supermen. Until 1943 or even 1944, when the war turned unmistakably against Japan, the cartoon rendering of the enemy was often a monstrously huge figure. Like the 9-11 Commission, more sober commentators responded by warning of the danger of exaggerating the enemy’s resources and capabilities to the point where this became demoralizing. A typical essay in the Sunday New York Times Magazine in March 1942, for example, might have served as a draft for post–September 11 warnings about being carried away by the specter of an unslayable hydra of destruction. It was titled “Japanese Superman? That, Too, Is a Fallacy.”33

John Dower is Ford International Professor of Japanese history at M.I.T. His numerous publications include War Without Mercy: Race and Power in the Pacific War, and Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II, which won the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award. He is an Asia-Pacific Journal Associate. His new book, from which the present article is excerpted is, Cultures of War: Pearl Harbor / Hiroshima / 9-11 / Iraq.

Laura Hein teaches Japanese history at Northwestern University and works on democratization in postwar Japan in a variety of institutional settings. She is an Asia-Pacific Journal coordinator. A co-editor of Living With the Bomb: American and Japanese Cultural Conflicts in the Nuclear Age, her book in press is Imagination Without Borders: Feminist Artist Tomiyama Taeko and Social Responsibility. She wrote this introduction for The Asia-Pacific Journal.

Recommended citation: John Dower and Laura Hein, “The Failure of Imagination: From Pearl Harbor to 9-11, Afghanistan and Iraq,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 36-1-10, September 6, 2010.

Notes

1 Prange, Pearl Harbor, 515. Morgan recounted this to Prange in an interview in October -1976.

2 Report of the Joint Committee on the Investigation of the Pearl Harbor Attack, 259; Prange, At Dawn We Slept, 689; Wohlstetter, Pearl Harbor, -392.

3 Prange, Pearl Harbor, 552; Goldstein and Dillon, The Pearl Harbor Papers, -121.

4 Goldstein and Dillon, The Pearl Harbor Papers, -122.

5 The conflicting images of Japan at the turn of the century emerge vividly in several lavishly illustrated units on the “Visualizing Cultures” website produced at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology by John W. Dower and Shigeru Miyagawa. See visualizingcultures.mit.edu, and particularly “Throwing Off Asia” (in three parts), “Asia Rising,” and “Yellow Promise/Yellow Peril.” The latter two units are based on Japanese and foreign postcards of the Russo-Japanese War in the Leonard Lauder Collection at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and “Yellow Promise/Yellow Peril” is particularly illuminating on the ambiguous European response to Japan’s stunning emergence as a powerful imperialist -power.

6 Business Week, September 1, 1945. This ad is reproduced in John W. Dower, “Graphic Japanese, Graphic Americans: Coded Images in U.S.-Japanese Relations,” in Akira Iriye and Robert A. Wampler, eds., Partnership: The United States and Japan, 1951–2001 (Kodansha International, 2001), 304–5.

7 For general treatments of these matters, see Akira Iriye, Pacific Estrangement: Japanese and American Expansion, 1897–1911 (Harvard University Press, 1972); also Spector, Eagle against the Sun, esp. chs. 1–5. The 127 tests and revisions of Orange are noted in ibid., -57.

8 On the B-17 bombers, see Prange, Pearl Harbor, 145–52, 290–93; also Spector, Eagle against the Sun, 74–75. The three Pearl Harbor alerts are described in detail in Wohlstetter, Pearl Harbor, 71–169.

9 See, for example, Michael A. Barnhart, Japan Prepares for Total War: The Search for Economic Security, 1919–1941 (Cornell University Press, 1987).

10 Prange, Pearl Harbor, 537, 555–56; Wohlstetter, Pearl Harbor, 336–38; E. Kathleen Williams, “Air War, 1939–41,” in Wesley Frank Craven and James Lea Cate, eds., The Army Air Forces in World War II, vol. 1: Plans and Early Operations, January 1939 to August 1942 (University of Chicago Press, 1948), 79–80. On the development of the Mitsubishi Zero as seen from the Japanese side, see the translated account by the chief designer Jiro¯ Horikoshi, Eagles of Mitsubishi: The Story of the Zero Fighter (Washington University Press, 1980); also Akira Yoshimura, Zero Fighter (Praeger, 1996).

11 Prange, Pearl Harbor, 550, 569; H. P. Willmott, The Second World War in the Far East (Smithsonian Books, 1999), 54, 66, 78, 83–84; Russell F. Weigley, The American Way of War: A History of United States Military Strategy and Policy (Indiana University Press, 1973), -276.

12 For an archives-based analysis of World War II in Asia that is acutely sensitive to (and quotable about) Anglo racism, see Christopher Thorne, Allies of a Kind: The United States, Britain, and the War against Japan, 1941–1945 (Oxford University Press, 1979). American racism vis-à-vis Asians was complicated by the positive attitude many Americans had come to hold toward China by the late 1930s. Although “anti-Oriental” movements and legislation constitute a deep stain in U.S. history of the nineteenth and early twentieth century, sympathy toward the Chinese in their struggle against the Japanese was strong—a development that derived in considerable part from the exceedingly effective positive image of the Chinese purveyed by popular writers such as the Nobel Prize–winning Pearl Buck. I address these matters at length in War Without Mercy: Race and Power in the Pacific War (Pantheon, 1986).

13 It is worth keeping in mind that surprise attacks have been common in modern times. These include the attack by Germany on the Soviet Union in 1941; by North Korea on South Korea in 1950, and soon after this the entry of the People’s Republic of China into the Korean War; and the Tet offensive in the Vietnam War in -1968.

14 For examples of the bedrock assumptions noted here, see Ike, Japan’s Decision for War, 78, 80, 82, 148, 152, -160.

15 Ike, Japan’s Decision for War, 238, -246.

16 Katharine Sansom, Sir George Sansom and Japan: A Memoir (Diplomatic Press, 1972), 156 (MacArthur’s quote).

17 Goldstein and Dillon, The Pearl Harbor Papers, 155. For the Missouri surrender ceremony, see Samuel Eliot Morison, History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, vol. 14: Victory in the Pacific (Little, Brown, 1960), 362–63. The flag that had been flying over the Capitol on December 7 had previously been displayed at Casablanca (where the Allied policy of “unconditional surrender” was announced in February 1943), Rome, and -Berlin.

18 Japan’s vision of what was needed to be secure and self-sufficient escalated steadily after the Manchurian Incident of 1931, with huge leaps taking place in 1937, with the invasion of China; in mid-1940, with the movement of Japanese forces into northern French Indochina; and of course in 1941, when the “move South” precipitated the attack on Pearl Harbor. As the empire expanded, so inevitably did the political rhetoric that accompanied it. Thus, the proclaimed “New Order” of 1938 (embracing Japan, China, and the puppet state of Manchukuo) metamorphosed into the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere in 1940. Until around 1936, advocates of the “move South” fought a vigorous internecine battle with proponents of a “move North” against the Soviet Union, aimed at seizing the strategic resources of the Soviet Far East. (The Japanese army was more inclined to “move North” than the navy.) The “move North” argument continued to be advocated up to the eve of the Pearl Harbor attack, and the Americans were well aware of this from their intercepts of the Japanese diplomatic code. This was yet one more distraction—one more example of “noise”—that compounded the analysis of Japan’s intentions. Some high-level U.S. planners (such as Rear Admiral Richmond Turner of the War Plans Division) were so fixated on the “move North” possibility that, in the eyes of later critics, they seriously impeded balanced intelligence analysis; Prange, Pearl Harbor, 326–31, is strong on this. For a close analysis of the “rational” quest for autarky or autonomy that drove Japanese expansion from the Manchurian Incident to the war with China, see James B. Crowley, Japan’s Quest for Autonomy: National Security and Foreign Policy, 1930–1938 (Princeton University Press, 1966).

19 The 9-11 Commission Report, 341–42; Clarke, Against All Enemies, ch. 6 (133–54), esp. 148. Terrorist attacks on U.S. targets abroad also mark this period, of course, notably those in Beirut (1982), Libya (“Pan Am 103” in 1988), Somalia (1993, later identified as involving Al Qaeda), Saudi Arabia (1995–96), and Kenya and Tanzania (1998, instigated by Al Qaeda).

20 This timetable for planning the Pearl Harbor attack has been extracted from Prange, At Dawn We Slept, 15, 27–28, 101, 106, 157–58, 223–31, 299, 309, 324, 328, 345, 372. On Al Qaeda’s planning, see The 9-11 Commission Report, -365.

21 Warren I. Cohen, “The Role of Private Groups in the United States,” in Borg and Okamoto, Pearl Harbor as History, 421–58. The well-known scholars of Far Eastern affairs who urged conciliation with Japan included Payson Treat, A. Whitney Griswold, and Paul Clyde; ibid., 452–53. Cohen concludes his detailed study with the observation that “the American people remained overwhelmingly opposed to involvement in the Far Eastern conflict or in any war”; ibid., -456.

22 Grew abandoned his general policy of appeasing Japan in a famous “green light” cable to the State Department on September 10, 1940, but continued to maintain hope that U.S. responsiveness to Japan’s perceived interests would strengthen the influence of “moderates” within the Japanese government. His September 1941 advocacy of “constructive conciliation” came in conjunction with proposals for a personal meeting between Roosevelt and Prime Minister -Konoe.

23 Mira Wilkins, “The Role of U.S. Business,” in Borg and Okamoto, Pearl Harbor as History, 341–76. This excellent analysis includes useful tables and charts. For the Fortune opinion poll, see 350–51; Wilkins speculates that the poll, published in September 1940, was probably conducted in early July—just before the Roo-sevelt administration imposed the first serious restrictions on strategic -exports.

24 Steve Coll’s Ghost Wars: The Secret History of the CIA, Afghanistan, and Bin Laden, from the Soviet Invasion to September 10, 2001 (Penguin, 2004), won the Pulitzer Prize. See esp. 92–93, 97–98 on Casey; 90, 104 on translation of the Qur’an; 11, 125–37, 149–51, 175 on weapons and other support for the Afghan fighters; and 155 on moral support for the non-Afghan mujahideen. The U.S. role in playing midwife to the mujahideen is also documented in vivid detail in Robert Dreyfuss, Devil’s Game: How the United States Helped Unleash Fundamentalist Islam (Metropolitan, 2005), esp. ch. 11. The photograph of President Reagan meeting with mujahideen “freedom fighters” from Afghanistan is reproduced on the cover of Eqbal Ahmad, Terrorism: Theirs and Ours (Seven Stories Press, 2002).

25 Benazir Bhutto, Reconciliation: Islam, Democracy, and the West (HarperCollins, 2008), ch. 3, esp. 81–85, 149–55. Bhutto’s secret role in providing covert aid to the Taliban is noted in Coll, Ghost Wars, 289–94, 298–300.

26 Bin Laden, Messages to the World, 48 (March 1997), 65, 82 (December 1998), 109 (October 21, 2001), 192–93 (February 14, 2003). On the absence of counterinsurgency doctrine and training, see chapter 5 (notes 176–178 of this book).

27 Clifford J. Levy, “Poker-Faced, Russia Flaunts Its Afghan Card,” New York Times, February 22, -2009.

28 Freeman is quoted in Dreyfuss, Devil’s Game, 290–91 (from an April 2004 interview with the author).

29 Scheuer, Imperial Hubris, 197–98.

30 Clarke, Against All Enemies, 30–32, -232.

31 The 9-11 Commission Report, 339–48.

32 The 9-11 Commission Report, 364; Hersh, Chain of Command, 91–92; Michael A. Sheehan, Crush the Cell: How to Defeat Terrorism without Terrorizing Ourselves (Crown, 2008), 6, 14. Jack Goldsmith, a conservative lawyer who became head of the president’s Office of Legal Counsel in October 2003, devotes an entire chapter of his book to the role of “fear bordering on obsession” in driving post–9-11 administration policies; The Terror Presidency: Law and Judgment inside the Bush Administration (Norton, 2007), ch. 3 (esp. 71–76), also 165–67.

33 Nathaniel Pfeffer, “Japanese Superman? That, Too, Is a Fallacy,” New York Times Magazine, March 22, 1942. In a book written many years ago, I dwelled at length on images of the enemy from both sides of the war in the Pacific, including the metamorphoses of the Japanese from little men to supermen. See War Without Mercy, esp. ch. 5 (“Lesser Men and Supermen”). This is not a unique phenomenon, and need not involve race. A similar “little men to supermen” transformation took place, for example, in the so-called missile-gap crisis that followed the Soviet test of an intercontinental ballistic missile in -1957.