Fujiwara Chisa

Since the 1990s, Japan has experienced an increase in the number of single parent families due to a significant rise in the divorce rate. In response to this trend, the Japanese government introduced welfare reforms in 2002, which aimed to limit welfare expenditures for single mothers and strengthen mothers’ self-sufficiency through work. Becoming self-sufficient through work, however, is not just a matter of will and effort. As I will show in this paper, a single mother’s ability to find employment is strongly influenced by her educational and class background, an issue which until recently has received comparatively little attention. In what follows, I examine single motherhood in Japan from the perspective of social class. Poverty and social class are rarely discussed in studies of Japanese society, in part because Japan is widely considered to be a quite affluent and egalitarian society. However, social class, which is chiefly explored through educational background in this paper, is an important factor that affects the living conditions of single mothers in contemporary Japan. [1]

Section 1: Single mothers and welfare reform in Japan

Welfare reform

As in other industrialized countries, welfare support for single parent families has become a major concern of policymakers in Japan. Because of a significant increase in the number of divorced and unmarried mothers, as well as their tendency to rely upon public support, welfare expenditures on single mothers (not including widowed mothers who receive widow’s pensions) has been subject to reform in Japan.

In light of these concerns, policymakers in Japan have seen the recent reforms in the United States and the United Kingdom as an attractive model. In the U.S., welfare reforms introduced in 1996 have tried to limit welfare expenditures through the introduction of welfare-to-work policies, and have dramatically reduced single mothers’ reliance on cash assistance. Similarly, in the U.K., the New Deal policy for lone parent families introduced in 1997 aims to reduce poverty among single parent families through the introduction of welfare-to-work policies. Likewise, in Japan, the dependent children’s allowance (jido fuyo teate), which is the major source of support for divorced and unmarried mothers, has been subject to restructuring in the past two decades. In response to increasing demand, policymakers have tightened the conditions for eligibility and reduced both the amount of benefits and the number of recipients in a series of cuts carried out in 1985 and 1998. As in the U.S. and the U.K., policymakers in Japan have been concerned with the increasing caseloads and welfare expenditures.

In 2002, the Japanese government introduced a number of reforms, which aimed to limit welfare expenditures for single mothers. Since 2003, single mothers have been subject to a time limit, which reduces the dependent children’s allowance for mothers who have received the allowance for more than five years or who have been single mothers for more than seven years. In lieu of cash assistance, a number of services and programs have been extended to support single mothers’ access to work and income. The revised law about single-mother families (boshi kafu fukushi hou) of 2002 stipulates that single parents are given preference in placing their children into subsidized day care centers. Under the new 2003 regulation for child support enforcement, single mothers are able to not only lay claim to past unpaid child support payments, but also ensure that future payments will be taken directly out of the fathers’ paychecks. As work-related services, the Japanese government is urging local prefectures and cities to establish special job centers and job training benefits for single mothers.

The characteristics of single mothers in Japan

The goal of these programs is quite similar to that of the welfare reforms introduced in the U.S. and the U.K. The major objective is to increase employment among single mothers and to make them economically self-sufficient. On the surface, policymakers in the U.S., U.K. and Japan seem to face similar problems: burgeoning expenditures on welfare support for single mothers and increasing numbers of single mothers who rely on public support. However, the situation of single mothers in Japan differs quite significantly from other industrialized countries in several ways.

First of all, in comparison with the U.S. and the U.K., single motherhood in Japan is a marginal social phenomenon. Whereas the share of single mother families among all families with children is over 20 percent in the U.S. and the U.K., in Japan, they account for just 7 percent of families. Also, unmarried mothers in Japan accounted for only 8 percent of single mothers. In the United States, by contrast, over 40 percent of single mothers were unmarried. Moreover, most single mothers in Japan are in their 30’s and 40’s. Many become single parents only after marriage, childbirth, and divorce. Therefore, single motherhood in Japan is largely associated with divorced middle-age mothers rather than unmarried teenagers.

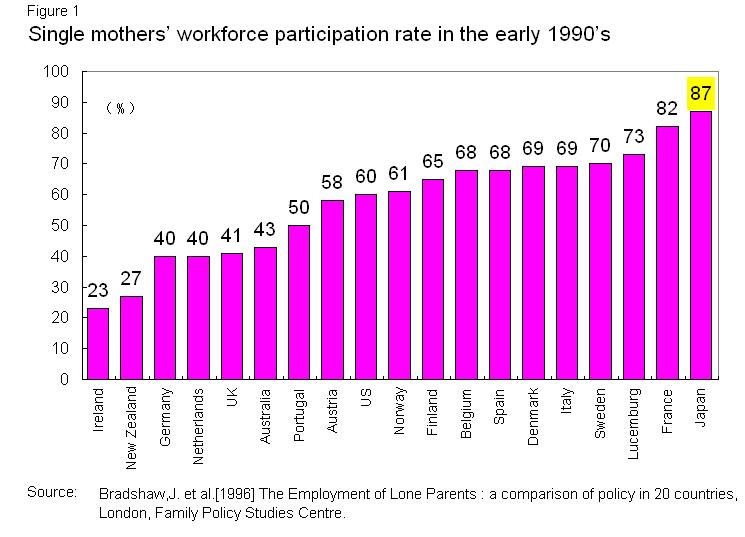

Figure 1. Single mothers’ workforce participation rate in the early 1990’s

Another characteristic of single mothers in Japan is that their work participation rate is the highest in the world, far exceeding the majority of other major industrialized countries (Figure 1). In the early 1990’s, an astonishing 87 percent of Japanese single mothers (including widows as well as divorced and unmarried mothers) were working. Even more striking is the fact that their work participation rate has been over 80 percent for the entire post-war period.

Figure 2. Married mothers’ workforce participation rate in the early 1990’s

Enlarge this image

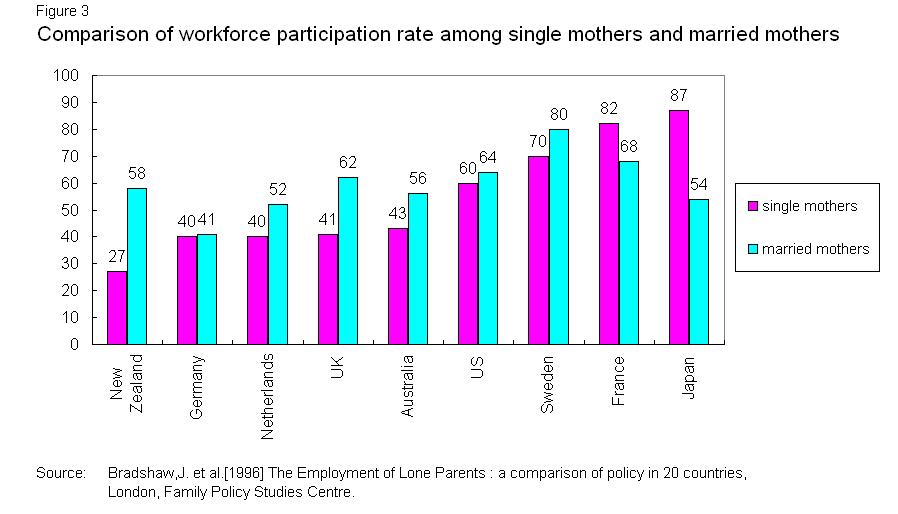

This may come as a surprise, because it is often assumed that most Japanese women are housewives. Indeed, in the 1990’s, only 54 percent of married mothers in Japan were working (Figure 2). This indicates that it remains common for Japanese women to stop working at the time of marriage and childbirth and to return to the labor market in middle-age. This makes the high work participation rate of single mothers all the more striking. As shown by Figure 3, the work participation rate of Japanese single mothers is over 30 percentage points higher than that of married mothers. A difference in the work rate of single mothers and married mothers in itself is not so unusual; it can also be seen in the United Kingdom and New Zealand. However, one particularity about Japan is that the work participation rate of single mothers, though not married mothers, is significantly higher.

Figure 4. Trends in the average annual income of households in Japan — including public and private transfer

Since almost all Japanese single mothers are working, one might assume that they are economically self-sufficient. Unfortunately, because of low salaries, it remains difficult for them to make ends meet on their incomes from work. In the 1990’s, the average annual income of single mothers amounted to less than 40 percent of the average Japanese household income (Figure 4). The increasing disparity in incomes can be explained by the growing number of dual-earner families with higher incomes. The low income of single mothers also illustrates persisting disparities in women’s and men’s average income: the average wage of women remains at about 60 percent that of men. Since the dependent children’s allowance supports mothers with low incomes, it constitutes a crucial contribution to the welfare of single mothers and their children.

The political background of welfare reform in Japan

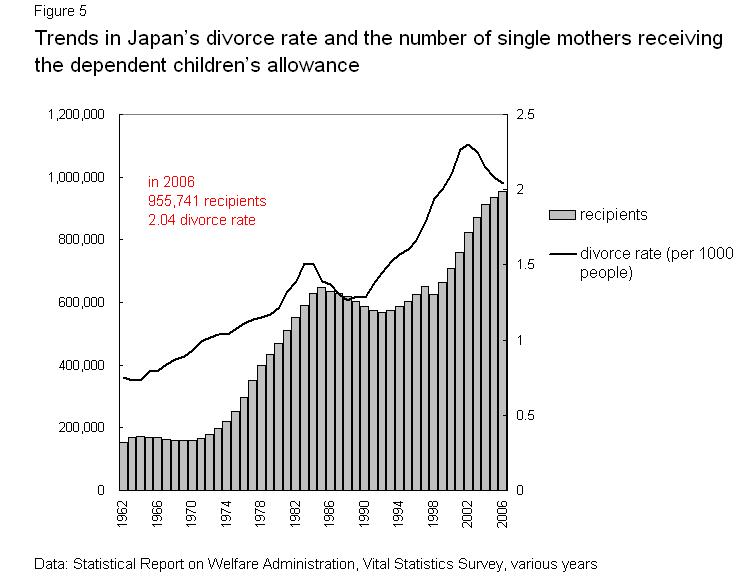

One may wonder why, in light of the high work participation rate of single mothers, the Japanese government has introduced new regulations which aim to strengthen mothers’ self-sufficiency through work, that is, to reduce state support. It was the continued increase in divorces, and therefore demand for government assistance, rather than a lack of engagement in work, that made policies toward single mother a focus of policy revisions. As Figure 5 shows, Japan’s divorce rate has increased significantly in the 1990s. Since most single mothers (71% in 2003) qualify for the dependent children’s allowance because of low income, this led to a significant increase in the demand for the dependent children’s allowance.

Figure 5. Trends in Japan’s divorce rate and the number of single mothers receiving the dependent children’s allowance

The main reason for the reforms was the government’s need to reduce expenditures in order to cut back on deficit financing. In addition, public discourse began to portray the increasing divorce rate as a modern phenomenon associated with Western countries. It is widely believed that higher educational attainment and economic independence among women has contributed to the rising divorce rate [2]. Based on the assumption that divorcees are making a personal choice, policymakers argued that mothers should not feel entitled to government support. The low income of single mothers has often been explained by the lack of work experience of women who became housewives after having children.

Class aspects of single motherhood

What is missing from this picture are the socio-economic dimensions of divorce trends. Many studies in other industrialized countries have investigated the relationship between single parent families, poverty, and social class. They have shown how the economic disadvantages of single parent families are related to class, race, ethnicity, and gender inequality. So far, no analysis of this kind has been done in Japan. This is in part due to the lack of divorce statistics which specify socio-economic background. Statistics on single mothers also rarely indicate educational background and work patterns.

Even more striking is the fact that the Japanese government has no official data assessing the poverty rate. As a matter of course, the government counts and releases the number of recipients of public assistance (seikatsu hogo), but does not seem to be interested in how many people fall through the cracks of the public assistance system. The government does not count the number of households living under the poverty line and does not release the take-up rate of public assistance system. The absence of such data has made poverty invisible in Japan. However, as in other industrialized countries, educational attainment as a factor of class background is an important issue.

Section 2: Educational attainment and employment patterns among single mothers

Data

In this section, I discuss the findings of a study group which looked at employment support services for single mothers. This group met between 2000 and 2002 with support from the Japanese Department of Labor. As a member of this group, I conducted several studies concerned with the work patterns of single mothers. The resulting group report was the first intensive study on the working conditions of single mothers in Japan.

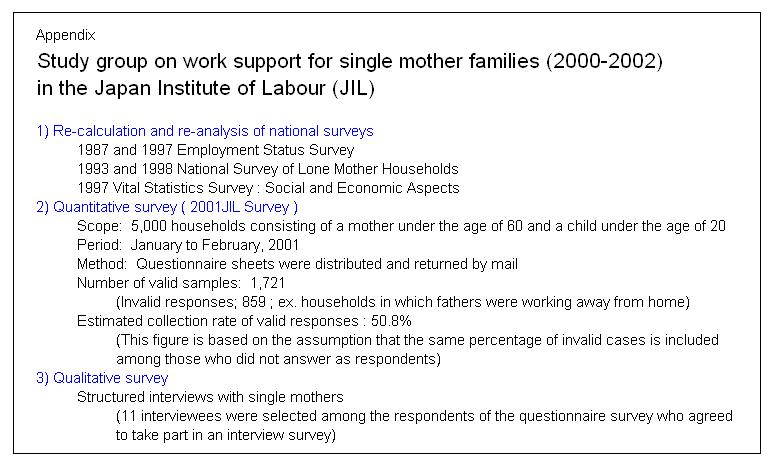

Appendix. Study group on work support for single mother families

Our research examined single parent families from several angles. First, we recalculated and analyzed several national surveys conducted by major Japanese ministries and government offices. Until then, raw data about single mother households had not been made available to individual researchers. The different datasets allowed us to compare the situation of single parents with that of married parents. We also conducted a quantitative survey with a random sample of single mothers based on the Population Census. Finally, we collected qualitative data based on interviews with single mothers. The members of this group were not particularly concerned with the class dimension of single motherhood. However, unexpectedly, our findings indicated that there were significant differences in the educational attainment of married parents and single parents.

Differences in educational background

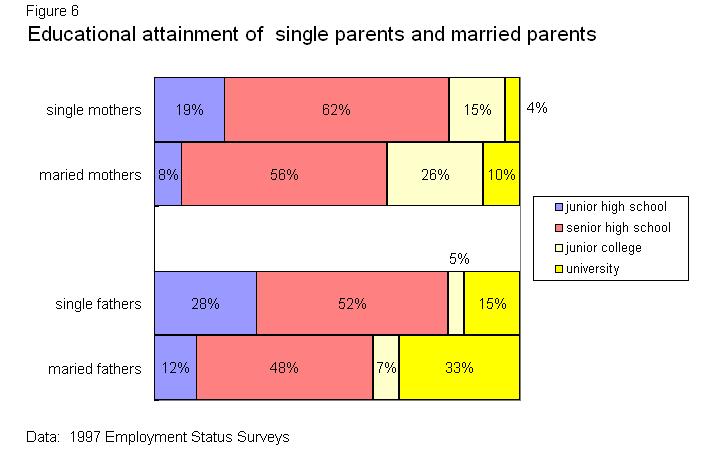

Figure 6 shows the result of a re-calculation of the Employment Status Survey of 1997. This survey is one of the largest government surveys and covers about 20,000 households. Although it includes single parent households, reports usually do not single out single mothers. The government however gave us special permission to recalculate the results in order to investigate the situation of single mothers in greater detail.

Figure 6. Educational attainment of single parents and married parents

Since there had been no existing data on the educational attainment of single mothers in Japan, and single motherhood is not as strongly associated with race, ethnicity and class in public discourse as in other industrialized countries. We were surprised to find that the educational attainment of single parents (mothers or fathers who had no spouse and lived with their own children under the age of 20) was very low. They tend to be graduates from junior or senior high school, whereas a significant proportion of married parents (mothers or fathers who lived with their spouses and their children under the age of 20) are junior college or university graduates. Among single mothers, 19 percent had not gone beyond junior high school. Among married mothers, by contrast, the ratio of junior high school graduates was just 8 percent. Moreover, 10 percent of married mothers have university degrees, whereas only 4 percent of single mothers do so.

The same tendency can be seen among single fathers. 28 percent of single fathers have only a junior high school degree, as opposed to 12 percent of married fathers. The ratio of single fathers who are university graduates is 15 percent, a rate lower than half of that of married fathers. Certainly, in terms of the age structure, single parents are on average older than married parents, so the differences of the educational attainment may be an effect of age. However, data from the Population Census also shows that single parents tend to have a lower educational attainment.

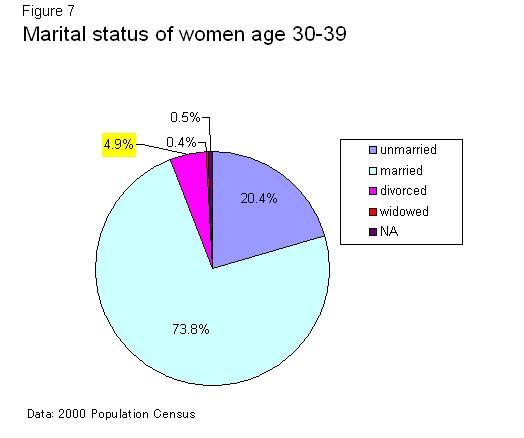

Figure 7. Marital status of women age 30-39

Figure 8. Variation in educational attainment and marital status of women age 30-39

The pie chart (Figure 7) depicts the attributes of Japanese women in their 30’s based on data from the Population Census of 2000. Among this sample of women, 73.8 percent were married, 20.4 percent were unmarried, and only 4.9 percent were divorced. The bar graph (Figure 8) indicates the educational attainment of married and divorced women. As shown in the figure, 12 percent of divorced women have only junior high school degrees. The ratio for married women of the same age is only 4 percent. Among divorced women only 6 percent were university graduates, but in the case of married women, 13 percent had university degrees. The same tendency can also be observed in other age groups and men.

Taking these observations as a point of departure, I will now examine the relationship between single mothers’ work patterns, incomes and educational attainment. Unfortunately, it is difficult to perform the same analysis for single fathers because of limited data availability.

Educational attainment and workforce participation among single mothers

Figure 9 illustrates the workforce participation rate of single mothers and married mothers. One significant finding here is that the workforce participation rate of single mothers with only a junior high school degree is lower than that of single mothers who are university graduates. Interestingly, the relationship between educational attainment and workforce participation rate is inverted in the case of married mothers. The workforce participation rate of married mothers is lower for university or college graduates. What this means is that highly educated married women tend not to work because their husbands bring home an ample salary. Japanese social policies in the areas of tax, insurance and pensions encourage married women to limit their outside paid work and remain dependent on their husbands. Consequently, many women stopped working when they were married.

Figure 9. Educational attainment and workforce participation of single mothers and married mothers

Changes in women’s work status in becoming a single mother

Another issue that has to be examined is how mothers make the transition from housewife to worker. Our survey allowed us to look at this process through which women became single mothers more closely. Figure 10 shows changes in the working status of single mothers. Before they became single mothers, 38 percent of women were not working, meaning that they were full-time housewives. Immediately after becoming single mothers, this ratio decreased to 17 percent. By the time of survey, only 13 percent were not working. In correspondence with the decreasing number of non-working mothers, the number of permanent employees among single mothers increased from 20 percent to 37 percent during the same period. Those without permanent employment were working part-time, in short-term contracts, or were self-employed.

Figure 10. Work status of single mothers

This means that even before the introduction of schemes aiming to promote employment among single mothers, becoming a single mother has meant for most women entering employment or changing their work status to full-time or permanent positions. These dramatic shifts in the working status of single mothers demonstrate their strong incentives to work. It must be added, however, that these trends do not apply evenly. We found significant differences in the probability of single mothers finding permanent employment depending on their educational attainment.

Educational attainment and single mothers’ work status

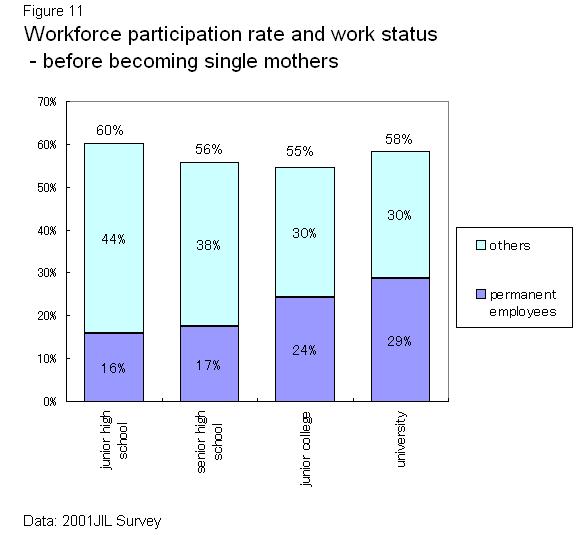

Figure 11 indicates the workforce participation rate and work status of single mothers before they became single mothers. As in the case of married mothers, there are no significant differences in the workforce participation of single mothers. However, in terms of work status, only a quarter of single mothers with junior high school degrees held permanent positions, whereas half of single mothers with university degrees worked as permanent employees.

Figure 11. Workforce participation rate and work status — before becoming single mothers

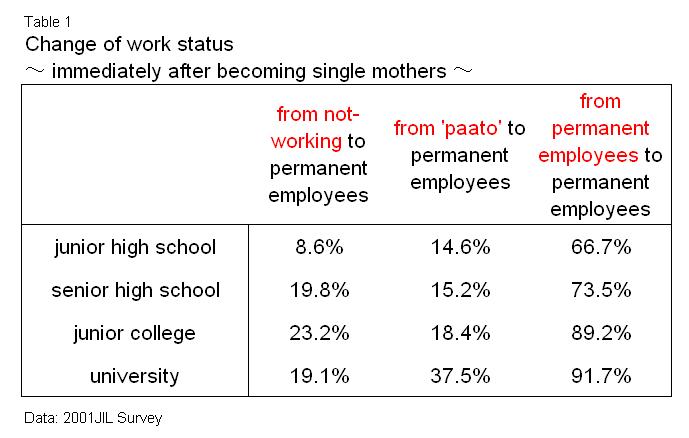

There were also differences in the process through which women became permanent employees (Table 1). The percentage of women who were not working before becoming single mothers but became permanent employees immediately afterward was 19.1 percent for university graduates, but only 8.6 percent for junior high school graduates. In addition, the ratio of women who were previously working as a paato, which refers to quasi part-time jobs, but became permanent employees immediately after becoming single mothers, was 37.5 percent for university graduates, but only 14.6 percent for junior high school graduates. It seems therefore that single mothers with high educational attainment find it easier to find permanent employment than those with less educational attainment.

Table 1. Change of work status — immediately after becoming single mothers

Enlarge this image

Changes in women’s work participation rate as single mothers

There are also significant differences in the degree to which single mothers find employment and obtain a position as a permanent employee after becoming single mothers, depending on their educational attainment.

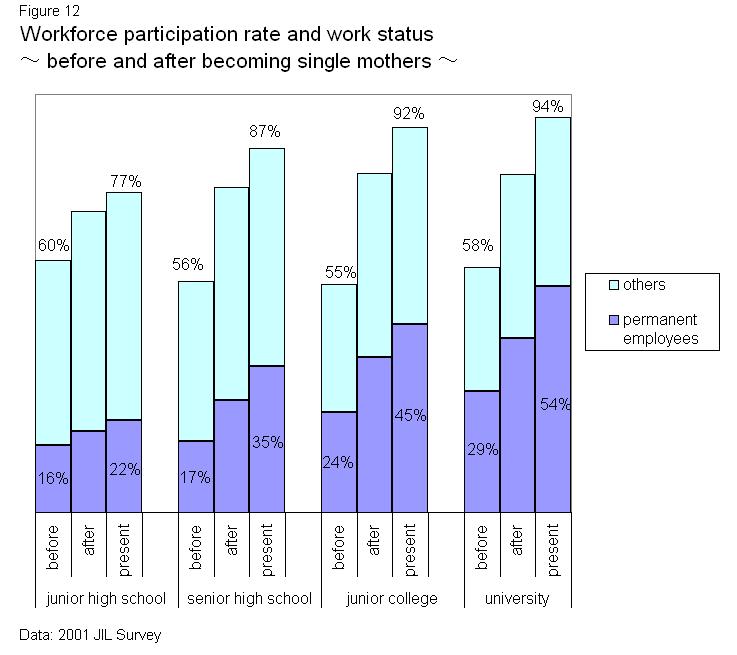

Figure 12. Workforce participation rate and work status — before and after becoming single mothers

First, according to Figure 12, the overall workforce participation rate of mothers who later became single mothers is almost the same as that other mothers regardless of educational attainment; only at the stage of becoming single mothers do we see differences. The workforce participation rate of single mothers who have higher educational attainment increases rapidly. The workforce participation rate of single mothers with lower educational attainment, by contrast, increases only moderately. As a result, at the time of the survey, there are significant disparities in the overall workforce participation rate: whereas only 77 percent of single mother junior high school graduates work, 94 percent of single mother university graduates are engaged in the workforce.

Second, it seems easier for single mothers with higher educational attainment to become permanent employees. This tendency also applies to the period preceding divorce, and persists after women become single mothers. For mothers with high educational attainment, work opportunities expand after they become single mothers. Currently, 54 percent of single mothers with a university degree are working as permanent employees, whereas only 22 percent of single mothers with no more than a junior high school degree have the same work status.

Educational attainment and income levels

As a final illustration, we will discuss the average income of working single mothers. The average annual income of working single mothers is 2.5 million yen. For permanent employees, the average annual income is 3.4 million yen. However, for paato, the average annual income is just 1.3 million yen. Paato is generally translated as “part-time workers”. The reason why I do not translate this term as “part-time workers“ is because in reality, ,paato workers do not necessarily work fewer hours than full-time workers. For example, the average working hours of single mothers who are working as paato is 33.8 hours per week (2001 JIL Survey). Over half of single mothers who are in paato positions work over 35 hours per week, just like permanent employees (50.9 percent in 2001 JIL survey, 54.4 percent in 1997 Employment Status Survey). In Japan, these workers are ironically called “full-time paato.” Therefore, I use the word “permanent employee” and paato instead of “full-time workers” and “part-time workers”. In summary, there is a large difference in the annual incomes of permanent employees and paato workers. However, even though becoming a permanent employee is the ideal for single mothers, there are significant differences within this status.

Figure 13 shows that there is no difference in wages among paato workers, regardless of educational background. However, in the case of permanent employees, we see a large gap. The average income of single mothers with a junior high school degree who are working as permanent employees is about 2.5 million yen. By contrast, the average income of university graduates working as permanent employees is approximately 4.6 million yen. In other words, it is not only more difficult for junior high school graduates to become permanent employees, but they also get paid significantly less than university graduates.

Figure 13. Variation of the average annual income of working single mothers by educational backgrounds

In summary, the workforce participation rate of single mothers in Japan is very high even though half of such women were not working before becoming single mothers. There are, however, significant differences in terms of single mothers’ ability to find jobs as permanent employees depending on their educational attainment. Single mothers with lower educational attainment find it more difficult to become permanent employees. Even when they became permanent employees, they still face a significant wage gap because of their low educational attainment. Most importantly, there is a tendency for single mothers to have a lower educational attainment than married mothers.

Section 3: Discussion

These findings have a number of implications for our understanding of single motherhood in Japan. Most observers of single mothers in Japan see their low income from work as the major problem. Even though Japanese single mothers are working, their incomes are not sufficient to make ends meet. This is also why the Japanese government has introduced work related services to reinforce their self-sufficiency through work. Although these are important issues, we also need to ask why the income of single mothers is so low.

Services and programs as a substitute for cash assistance

As single mothers’ incomes form wages remain low, government assistance in the form of the dependent children’s allowance has played an important role in assuring the welfare of single mothers and their children. However, the government has tried to reduce welfare expenditures, and in lieu of the dependent children’s allowance, a number of services and programs have been extended. Daycare services and vocational training programs are important elements for supporting working mothers, yet since many of them have been in existence for a long time, it is questionable whether they will significantly change the employment opportunities and incomes of single mothers.

Japanese policies have aimed to support the self-sufficiency of working single mothers through various programs and services. One of the oldest programs, established in 1953, is a low or no-interest loan program (boshi fukushi shikin), which is administered by single mother consultants (boshi soudan-in) in welfare offices. These loans can be used for various purposes, such as children’s education, vocational training and establishment of a small business such as a dry cleaning shop or tobacco store.

In terms of affirmative labor market policies, from 1960’s to 1970’s, job centers (koukyo shokugyo anteijo), which are available nation-wide and serve all types of job seekers as well as the unemployed, set up special sections for a group labeled ‘hard to employ’ (shushoku kon-nan sha). Since that time, single mothers in Japan have been traditionally considered one of the ‘hard to employ’ groups (other groups including the elderly, disabled, minorities (douwa chiku syusshin sha), former coal miners and so on), and thus have been eligible for a range of special work-related programs. Individuals who seek to strengthen their qualifications can also apply for subsidized vocational training in various job categories. Businesses which employ the ‘hard to employ’ can apply for a wage subsidy for the first year of their employment.

Although the revised law of 2002 stipulated that single parents be given preference in placing their children in subsidized day care centers, it is merely a statutory recognition of a continuing condition for many years. According to a 1998 survey, the majority of single mothers used day care centers to care for their children (61 percent) or sent them to kindergartens (13 percent). In contrast to the U.S. and the U.K., where informal and in-home care is common, only 12 percent of single mothers in Japan reported relying on family members or relatives (2 percent).

In addition, only very limited numbers of single mothers are ensured future child support payments by the new regulation of 2003. One reason is that in Japan, over 90 percent of divorces are settled by mutual agreement (kyogi rikon), that is, out of court. Child support payments are required by Japan’s Civil Code, but are not enforced. Child support enforcement of this kind is only possible if child support payments have been officially agreed on in a divorce settlement. It should also be added that since 2002, 80 percent of child support payments are counted toward the single mothers’ income. Since child support payments even now are not guaranteed, and a higher overall income decreases the amount of the dependent children’s allowance, the new rule creates a significant disincentive for single mothers to pursue child support payments.

Persistent wage gap between men and women

Even though the income of single mothers is very low in comparison to that of other families, it should be noted that their income is actually not lower than that of married mothers and other women. According to our data from the Employment Status Survey of 1997, the average annual working income of single mothers was 2.2 million yen, whereas the average working income of married mothers was only 1.9 million yen.

If single mothers are earning more than other women in the workforce, why is there such a widespread perception that their incomes are low? Why do they have difficulties providing for themselves and their children, even though they earn more on average than married mothers and all women? Evidently, this is not because of a lack of effort, but rather because the average wage of men is significantly higher than that of women. The average wage of married fathers was 5.9 million yen in 1997. Adding to this, many families now have two wage earners. Single mothers, by contrast, have to bring up their children with just one income in a gendered labor market. Consequently, these families find it difficult to maintain the same standard of living as two parent families.

A further observation deals with the persistent wage gap between men and women in Japan and the generally difficult working conditions facing women. According to the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), Japan ranks 42nd in the world on the Gender Empowerment Measure (GEM) in 2004. In terms of the Human Development Index (HDI), however, it ranks 7th in the world. To address this disparity between a high human development index and continuing gender inequalities, the Japanese government has made an effort to promote a gender-equal society, and has also shifted its social policy model from a male-breadwinner family with a full-time housewife to dual-earner family. Evidently, addressing gender inequalities is an important element for improving women’s status, especially in the area of the labor market.

Yet, from the perspective of single mothers, this approach to gender-equality through social policy is not entirely satisfactory. In essence, even though an increase in working women and working mothers may be seen as an improvement in women’s status, it has adverse effects on single mothers: the increase in working women and dual-earner couples has the potential to amplify the disparity between the incomes of one-parent and two-parent families. It may make it easier for women in general to work, but will not necessarily help them to earn a living wage.

Class dimensions of single motherhood

A final point concerns the continuing increase in the divorce rate in Japan in the 1990’s. It is widely believed that the rising divorce rate is a consequence of the higher educational attainment and economic independence of women. This view has also justified a reduction in welfare expenditures for single mothers’ families, and a growing focus on self-sufficiency through work over government assistance. However, as I have shown in this paper, the educational attainment of single parents actually tends to be lower than that of married parents.

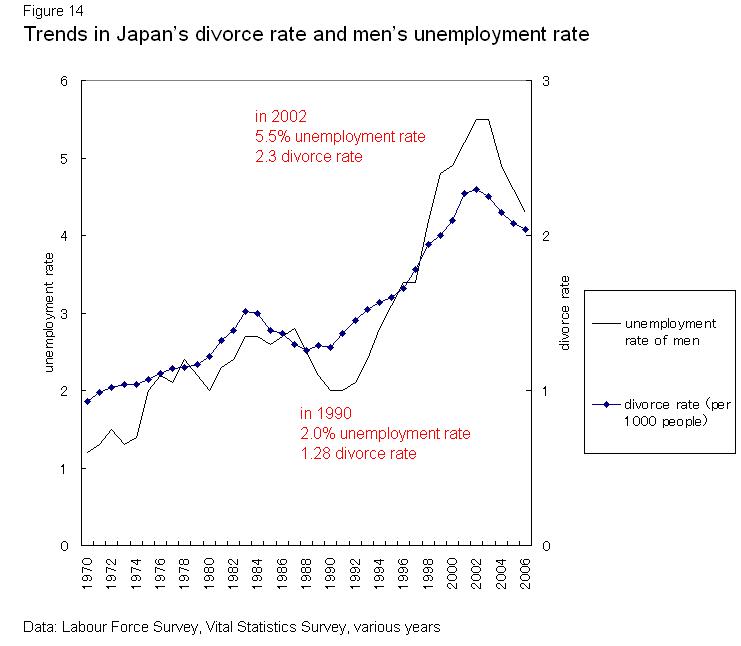

I suppose that there are two potential explanations for this. First, those with lower educational attainment have a higher tendency to divorce or become widowed than couples with higher educational attainment. The other possible explanation is that it may be more difficult for those with lower educational attainment to remarry. Unfortunately, there is no available empirical data to confirm these hypotheses. In Japan, as described in Figure 14, however, the trends in the divorce rate are quite similar to those in men’s unemployment rate. In the 1990’s, Japan was mired in a serious recession which caused unemployment to rise to unprecedented levels. It could be argued that since divorced men and women tend to have a lower level of educational attainment, an increasing risk of unemployment might lead to a rise in the tendency to divorce.

Figure 14. Trends in Japan’s divorce rate and men’s unemployment rate

It is often assumed that marriage in Japan is a system of economic security for women. Marriage, in other words, is often considered as the lifetime employment of women. However, this only applies to cases where the husband is able to provide for his wife and children on a single salary and has job security. As we have seen, however, although 38 percent of women are housewives prior to divorce, many women do work not only prior to but during marriage and after giving birth to children, possibly for financial reasons. Unfortunately, there is no data that can clearly show the relationship between unemployment, divorce, educational attainment, and socioeconomic background. However, it could be argued that individuals and families with a lower educational attainment are more vulnerable to economic crisis than those with higher educational attainment, and that for women in such situations, marriage does not constitute a reliable source of economic security. In light of the difficult living conditions of single mothers with lower educational attainment, as well as their high representation among single mothers, there seems to be little evidence to support the claim that the recent increase in divorce and single mothers is a sign of women’s growing economic independence. Instead, it might be better considered as a sign of a declining ability for women to rely on husbands and marriage for their livelihood.

Section 4: Conclusion

My analysis highlights several distinctive aspects about the situation of single mothers in Japan. First, unlike in most advanced industrialized nations, there are comparatively few single mothers in Japan. In addition, whereas limited participation in the workforce, and reliance on the welfare system has become a problem in other countries, in Japan the workforce participation rate of single mothers is strikingly high. It may be that because of the limited presence as well as high workforce participation rate, single mothers have attracted relatively little attention in public discourse. There are no stories of “welfare queens” who take advantage of the welfare state, or the reproduction of single parenthood through teenage pregnancy. Most importantly, rather than being part of a disadvantaged class or minority group, single mothers have been assumed to be middle class women whose choice to divorce is facilitated by their educational attainment and “economic independence”. This trend may also have been influenced by the general assumption Japan is a middle-class society, since 90 percent of the population identify themselves as such.

Consequently, social class is not only invisible, but has also not been considered as a factor influencing the situation of single mothers in Japan. Since single mothers also earn on average more than married women, one might not consider them to be in a disadvantaged position. However, as my analysis has shown, single mothers have on average a lower educational attainment than other mothers, meaning that many come from lower-class backgrounds. There are also significant disparities in incomes as well as ability to secure a permanent job among single mothers. The low income of single mothers is not only a consequence of gender inequality in the labor market, but is also due to lack of work opportunities for women with a lower educational attainment. Even though some single mothers with university education may do quite well, those with less than a senior high school degree face great difficulties. It is difficult for mothers with a junior high school degree to obtain a permanent job, and even when they do, their incomes are significantly lower than those of mothers with university degrees. To raise the incomes of single mothers, therefore, involve not only work opportunities, but also greater chances for educational advancement.

Viewed from this perspective, recent cuts in welfare support for working single mothers in Japan may cause great difficulties for single mothers with low educational attainment and income. Rather than chastising single mothers for their personal choices, policies need to address the problems and difficulties single mothers face as part of the working poor. After a decade of recession, it is high time to dismantle the middle-class myth and address existing class inequalities in Japanese society.

Fujiwara Chisa is an Associate Professor in the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences at Iwate University. She is the coauthor with Aya Ezawa of “America fukushi kaikaku saikou [Reconsidering U.S. Welfare Reform : An Analysis of Welfare Policies and Their Implications for Japan].” Kikan shakai hosho kenkyu [The Quarterly of Social Security Research] Vol.42, No.4. p.407-419.

This is a revised and expanded version of a paper that appeared in Japonesia Review on September 14, 2007. Posted at Japan Focus on January 2, 2008.

Notes:

[1] The author would like to thank Aya Ezawa for help in revising this paper.

[2] The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (kosei rodo sho) in a bulletin (No.102, May 19 2003) on the reforms explained: “There are a variety of the reasons behind the rise in divorce, and one can not pinpoint out a particular one. However, one of the factors is a decrease in the difficulties of divorcing compared to before, due to a change in attitudes toward divorce and increasing economic independence among women.”

References:

Ezawa, A. and Fujiwara, C. (2005a). “Lone Mothers and Welfare-to-Work Policies in Japan and the United States.” Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare Vol.32, No.4. p.41-63.

Fujiwara, C. (2005b). “Hitorioya no shugyo to kaisosei [Class Aspects of Single Parents’ Work Patterns].” Shakai-seisaku gakkai shi [The Journal of Social Policy and Labor Studies] No.13. p.161-175.

Fujiwara, C. (2007a). “Boshisetai no kaiso bunka [Class Differences among Single Mother Households: Identifying Policy Targets based on the Characteristics of Recipients of State Assistance].” Kikan kakei keizai kenkyu [Japanese Journal of Research on Household Economics] No. 73. p10-20.

Fujiwara, C. and Ezawa, A. (2007b). “America fukushi kaikaku saikou [Reconsidering U.S. Welfare Reform : An Analysis of Welfare Policies and Their Implications for Japan].” Kikan syakai hosho kenkyu [The Quarterly of Social Security Research] Vol.42, No.4. p.407-419.

Fujiwara, C. (2007c). “Koyo to fukushi no saihen [Reorganization of Work and Welfare].” M. Adachi et. al (eds.) Feminist politics no sintenkai [The Evolution of Feminist Politics]. Akashi shoten.

Nihon rodo kenkyu kiko [The Japan Institute for Labour] (2003). Boshisetai no haha e no syugyo sien ni kansuru kenkyu [A Study on Work Assistance for Single Mothers]. JIL Research Report No.156.

(Summary in English here.)