Twentieth Century Japanese Art and the Wartime State: Reassessing the Art of Ogawara Shū and Fujita Tsuguharu

Asato IKEDA

|

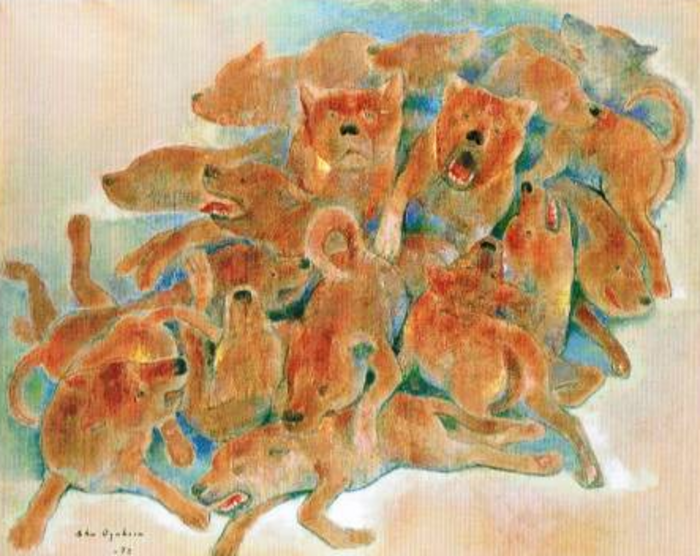

Ogawara Shū, A Herded Society, 1973 |

In 1973, Ogawara Shū (1911-2002) painted a group of Hokkaido dogs in A Herded Society (Gunka shakai). Barking, crawling over each other, and trying to jump out of the picture plane toward the viewer, these are not tame, docile pet dogs, but rather violent animals. The painting does not have a smooth finish or a focal point. The simultaneously expressive yet unsophisticated faces of the dogs add a childish quality to the work. The artist stated that this painting represented the group mentality that existed among Japanese people, not only during the war when they supported the military government without question, but also after the war when they began uncritically embracing U.S. policies. Yet, distancing oneself from the pack is not easy.

|

Ogawara Shū, A Herd, 1977 |

Another painting A Herd (Mure, 1977) creates a sense of loneliness and isolation through the use of contrasting colors and body language. In the painting, a sad-looking dog, placed in the foreground and differentiated from the pack in the indigo background, looks toward the viewers as if to ask for consolation. The dogs in the pack have mean, scary faces and some of them are ready to pounce on the isolated one.

Echoing immediate postwar discussions by political scientist Maruyama Masao and the literary group Kindai Bungaku on wartime responsibility, blind feudalism, and the need to create subjective autonomy, Ogawara not only tackled the issue of the group versus the individual, but also confronted his long-silent past: he himself had belonged to the pack, collaborating with the military and painting war propaganda in the early 1940s.1 After the war, however, he disassociated himself from major art groups in Tokyo and moved to the small town of Kuchan in Hokkaido where he was raised. The lonely dog in A Herd may be seen as a self-portrait of the artist in the postwar era.

Similar to the United States, Britain, Germany, Canada, and Australia, Japan had its own official war art program during the Second World War.2 After Japan’s defeat in 1951, however, the United States confiscated one hundred fifty three propaganda battle paintings that had been commissioned by the Japanese Imperial Army, Navy, and Air Force between 1937 and 1945. It was only after 1967, when photographer Nakagawa Ichirō found this collection of War Campaign Record Paintings (sensō sakusen kirokuga) at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Ohio, that the public paid attention to the paintings once again. Nakagawa’s “discovery” of the collection spurred a war art repatriation movement in Japan in the late 1960s. The movement was led by nationalist politicians including Nakasone Yasuhiro and Ishihara Shintarō. Also among them were former war painters Miyamoto Saburō and Ihara Usaburō who called for repatriation, claiming that the war paintings were “masterpieces” (meiga) and “valuable ethnic monuments” (kichōna minzokuteki kinenbutsu).3 Critical reflections on wartime collaboration that took place in the field of literature initiated by Ara Masato of Kindai Bungaku in the 1950s never took place among former war painters. The war art collection was eventually returned to The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo in 1970 on “indefinite loan.”4 Although the National Museum curators planned a war art exhibition in 1977, they abruptly cancelled it over fear of political controversy, citing anticipated anger from formerly colonized nations. In fact, the museum has never displayed the collection in its entirety and it has long been considered taboo, or as Sawaragi Noi calls it, Japanese modern art history’s “Pandora’s Box.”5

It was during this time when the art remained hidden in the National Museum that Ogawara, the last living former war artist, discussed his paintings in an NHK television program titled “Hovering War Paintings” (Samayoeru sensō-ga).6 The program, which was filmed one year before Ogawara died in 2002, revealed that some artists such as Koiso Ryōhei deliberately destroyed their wartime works and pulled them from their exhibitions in the postwar period. Unlike Miyamoto, Ihara, or Koiso, however, Ogawara publically spoke of his personal responsibility. The ninety year-old artist determinedly stated, “I am responsible for the war paintings. If I do not take responsibility, who does?” He stated he would “not hide what he did” and he would “leave others to make a judgment.”7

In the summer of 2008, while the Ogawara Shū Museum located in the small town of Kuchan, Hokkaido, held a modest exhibition of his works titled The Real Landscape of Myself II, another former war painter was in the spotlight in Sapporo, the capital and largest city of Hokkaido. From July 12th to September 4th, the Hokkaido Museum of Modern Art held the Léonard Foujita Exposition, which was funded by the Hokkaido Shinbun newspaper and supported by the General Council of Essonne in France.8 It featured nearly two hundred works by Fujita Tsuguharu (1868-1968), also known as Léonard Foujita. Fujita was an internationally renowned artist of École de Paris, the school of non-French modernists who resided in Paris, the world art capital of the 1920s. He was arguably the most famous Japanese artist in the world during the prewar era. In Japan, Fujita was also known as a prolific wartime painter of the late 1930s and early 1940s. Due to his wartime activities he was ostracized for many years in postwar art circles, but following a large retrospective organized by The Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo in 2006, there was renewed interest in the man and his work. Although Ogawara and Fujita have never been discussed together, their concurrent exhibitions in Hokkaido in 2008 provide an opportunity to examine these two artists who lived through the twentieth century.

|

Fujita Tsuguharu, ca. 1920s (1886-1968) Ogawara Shū, ca. 1993 (1911-2002) |

This article introduces and compares the works and lives of Ogawara Shū and Fujita Tsuguharu. By comparing Fujita Tsuguharu with another war artist, I challenge the recent uncritical museological discourse about Fujita and reassess the lesser known artist Ogawara as well.9 In so doing, I attest to the significance of unraveling the wartime art, an effort only recently begun by academic researchers. I first compare the two artists, focusing on how they started out as modernist artists, produced war propaganda, and reflected on their wartime experiences in the postwar era. I will then examine the national investment in rehabilitating Fujita into the canon of Japanese modern art history, as in the 2006 and the 2008 exhibitions. Finally, I consider what research remains to be done regarding the wartime works of these two artists in particular and Japanese war art in general.

Ogawara Shū and Fujita Tsuguharu

Both Fujita and Ogawara established careers as prewar Japanese modernists who aspired to create art that was new and original. Tokyo-born Fujita Tsuguharu studied at the Tokyo School of Fine Arts, now known as the Tokyo National School of Arts, the most prestigious art school in Japan. Upon graduation in 1913, Fujita moved to Paris to study and became a member of École de Paris. There he made friends with globally acclaimed avant-garde artists including Pablo Picasso, Amedeo Modigliani, and Henri Matisse. He produced numerous works of female nudes, which emphasized thin yet assertive calligraphic black lines and the smooth, sensuous, transparent, and ceramic-like white surface of female skin. These nudes became his “signature style” and made him the most famous Japanese artist in Paris in the 1920s. Though numerous Japanese artists lived in Paris, their success did not compare with Fujita’s. In his Nude with Tapestry (Tapesurii no rafu, 1923) for example, he painted a fully naked woman with curled hair seated on a white silky cloth, stretching her legs out in front, putting her hands around her head, and exposing her underarm hair. The background, which could be a curtain placed behind her, is punctuated with soft pink flowers, and a cat sits beside the woman. A couch or a bed on which the woman sits appears unrealistic, seemingly lacking the appropriate mass in its material. The woman does not recede in space, which creates a slight disjuncture in spatial coordination especially in the lower part of the painting: the woman appears to be floating in space. Locating himself in modernist art practice in Europe, where artists turned to non-European cultures to transcend European artistic traditions, Fujita’s use of line and his attention to the sleek, concealed quality of the canvas was rather strategic. He was fully aware of the potential of Japanese art in early 20th century Europe: “The new artistic tendency recently in Europe is ‘simplicity’. In other words, Western art is becoming Orientalized, Japanized…The reason why I was able to establish my career in Paris was that my paintings contained elements of Japanese-style painting.”10

Ogawara, by contrast, never studied abroad. In 1929 he moved to Tokyo, Japan’s artistic metropole, and after graduating from the Tokyo School of Fine Arts, joined gatherings of young Japanese artists such as École de Tokyo and The Art and Culture Association (Bijutsu bunka kyōkai). Ogawara’s main interest was in surrealism, which developed first as a literary movement in the 1920s and then as a visual art in the 1930s. Ogawara associated closely with Fukuzawa Ichirō, a leading avant-garde artist who studied in France and introduced surrealism to Japan. Adapting surrealism to the Japanese milieu, Ogawara discovered atmospheric mysticism (jyōshoteki shimpisei), which he considered to be the principle of the surreal, in the natural environment of Northern Japan (hoppōteki seikaku).11 As late as 1940, he painted in a surrealist style, exploring the inner subjectivity of humans, the realm of the unknown, the unconscious, and the uncanny.

|

Ogawara Shū, Snow, 1940 |

In Snow (Yuki, 1940), he combines the dream-like quality of surrealism with Hokkaido’s landscape of snowy mountains, from which a massive human leg appears. Unlike his dog paintings in the 1970s, this painting shows thick application of paint and the artist’s ability to create spatial depth and join foreground and background in a plausible manner. Without an upper body, the leg in the foreground goes into the mountain with its booted sole facing the viewer. The leg is trapped by a craggy tree, the tip of which looks like a ski. The work communicates the menace of nature that could swallow a human, which Ogawara would have been well aware of from his experiences during Hokkaido’s ruthless winters. The dark side of nature, however, is contrasted with the brightness of the white snow and the blue, sunny sky, which gives the painting a mysterious, eerie edge. Like Fujita, Ogawara challenged the European academicism taught in art schools, but unlike Fujita, his goal was to bring “something new” to Japanese art per se.

What brought these seemingly disparate artists together was war. As militarists dominated the government in the 1930s, the social milieu that surrounded art and artists gradually changed. As early as 1935, the state explicitly intervened, consolidating art communities through the reform of the Imperial exhibition (teiten).12 With the beginning of the war with China in 1937, the government tightened its control on artists, officially commissioning propaganda works. According to art historian Kawata Akihisa, over three hundred artists participated in official war art production and painted War Record Campaign Paintings.13 Military official Akiyama Kunio defined War Campaign Record Paintings as paintings that “have the significant historical purpose of recording and preserving the military’s war campaign forever.”14 Another official, Yamanouchi Ichirō, advocated the realist style of European neo-classicism of the eighteenth and nineteenth century, especially works by Jacques-Louis David as proper models.15 The artists “served the nation” (saikan hōkoku) by exhibiting their works in state-sponsored exhibitions such as the Holy War Art Exhibition (Seisen bijutsu tenrankai) and by travelling to war fronts to record battles.

Artistic protest against the state was rare, and those who did not paint propaganda paintings were either sent to jail or the battlefield. Matsumoto Shunsuke, who wrote “The Living Artist” (Ikiteiru gaka) in 1941, was one of the very few artists who publicly protested against the militarist views of art.16 Referring to the symposium where militarist officials declared that artists should contribute to the war by painting propaganda paintings, Matsumoto wrote, “I regret to say in the symposium entitled ‘National Defense State and the Fine Arts’ I found no value. It is wise to keep silent, but I do not believe keeping silent today is necessarily the correct thing to do.”17 Meanwhile, the state set out to eradicate art that was deemed undesirable. Authorities and police labeled surrealist works “unhealthy” and linked them to “dangerous” thoughts of communism. In 1941 they arrested the leaders of the Japanese surrealist movement, Fukuzawa and Takiguchi Shūzō.18 In addition, numerous artists and art students were sent to the battlefield as soldiers.19

In the early 1940s, Ogawara and Fujita both produced works on government commission. Ogawara was initially drafted and dispatched to Manchuria as a soldier at the age of thirty in 1941. After succumbing to pneumonia, however, he was sent back to his home in Hokkaido. As for Fujita, in the 1930s he continued to paint and exhibit, and travelled extensively both inside and outside Japan (to Akita, Okinawa, Mexico, Brazil, and the United States). But in 1940, with Europe at war, he returned to Japan where he would stay for the duration of the war. Soon Ogawara and Fujita were on their way to the front, not as tourists or soldiers, but as official war artists. Both received public recognition through their war art: Ogawara received the Army Ministry Award (Rikugun daijin shō) and Fujita was awarded the Asahi Newspaper Culture Award (Asahi bunka shō), to name two. As President of the Army Art Association (Rikugun bijutsu kyōkai), Fujita occupied a higher and more prominent position than Ogawara. He stated in the art magazine Shin bijutsu in 1943: “I feel that I have dedicated my right arm to the nation. How rewarding it is that painters can directly contribute to the nation!”20

Interestingly, both artists painted the same battle: the Japan-US battle on Attu Island near Alaska in 1943. Both paintings are currently in the war art collection at The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo mentioned above. The battle is known as the first incident in which the Japanese military employed the strategy of gyokusai, or collective suicide. As part of the Battle of Midway that started in June 1942, Japan occupied the Kiska and Attu Islands in Alaska. By May 1943 the Japanese troops ran out of food and weapons, and their commander, Colonel Yamazaki Yasuyo, decided to choose “the path of the Japanese warrior,” or death over life. Those who were injured and unable to fight were asked to commit suicide so that they would not be captured by the enemy. On the night of May 29, 1943, after performing banzai to the Emperor, the last forces waged a sudden attack on the Americans, which resulted in brutal, hand-to-hand combat. Except for 28 prisoners, all Japanese on the island (over 2,000 people) died, either killed by the Americans or blown up by their own hand.21 The following morning, the surviving Americans found piles of Japanese corpses.

|

Ogawara Shū, The Bombing of Attu, 1945 |

Ogawara and Fujita approached this battle differently. Ogawara’s The Bombing of Attu (Attsutō bakugeki, 1945), one of only three war paintings that he produced, portrays Japanese planes flying over the mountains of Alaska. Just like Snow, Ogawara paints mountains covered by snow, but this time he captures them from the aerial perspective. While a man’s leg was trapped in nature in Snow, in this painting, the mountains are dominated by the human technology or battle planes that nobly fly over them. Offering viewers a perspective from the cockpit allowed Japanese viewers to visually dictate the American territory of Attu.22 Although Attu is known for its gruesome battles, the painting does not depict them. However, since it was produced in 1945 and titled The Bombing of Attu, this painting showing the Japanese bombing of the island generates a curiously anachronistic effect, giving the impression that Japan had won the battle.

Fujita’s painting of Attu, which portrays the dramatic moment of the gruesome fight and images of hell, stands in stark contrast to Ogawara’s somewhat disengaged war propaganda. Honorable Death on Attu Island (Attsutō gyokusai, 1943) is a work that the artist, even after the war, called one of the most satisfying works of his career. In the painting, Fujita paints the collective suicide (the so-called gyokusai or “shattered jewels”) for which the battle became so well known. Japanese soldiers advance from the left, screaming and bayoneting Americans. Dark, earth-colored helmets, bayonets, and military uniforms emerge out of the mound in the foreground and form a solid, abstract pattern that echoes the high, rough wave-like pattern of the mountain landscape, creating a dynamic composition. In the mound, we also find bodies and faces of already dead soldiers. The man in the near center of the background, who raises his arm forward and looks directly at the viewers screaming, is Col. Yamazaki, who commanded Japanese force. The two soldiers who are on either side of Yamazaki are cruelly stabbing the body of the enemy with their swords. In Fujita’s work, which focuses on the violent encounter between the two forces, the death of every Japanese soldier is justified as inflicting damage, however small, on the Americans.

The war ended in 1945, but the two artists’ postwar lives and reputations in Japan were long overshadowed by their wartime experiences. In the immediate postwar years, Fujita and Ogawara were questioned about their personal responsibility and expelled from the New Art Association (Shin bijutsu kai) and the Art and Culture Association, respectively.23 It is worth noting, in contrast, that the first President of the Japan Artist Association (Nihon bijutsuka renmei), the largest postwar artist community established in 1947, was Ihara Usaburō, who had himself been a prominent war artist. Similarly, Yokoyama Taikan, who dedicated the sales of his paintings to the military and produced battle planes with his name on them, never stopped working in the postwar era. Given this, why were Fujita and Ogawara singled out and ostracized? Perhaps for Fujita, it was because of his high visibility as the President of the Army Art Association (Rikugun bijyutsu kyōkai), or the fact that the shocking rumors about his sex life in Paris during the 1920s made him an easy target. His enormous success both in 1920s France and in 1930s Japan might have made other artists envious as well. Ogawara was initially ousted for failure to pay his Association fee, but he did not challenge his expulsion over this seemingly small matter.

Facing criticisms that questioned his wartime responsibility, Fujita defended himself by claiming that artists were always pacifists by nature and thus could not be militarists.24 Putting the war controversy behind him, Fujita left Japan permanently in 1949, arriving in New York and returning to France the following year. In 1955 he became a French citizen and was baptized in 1958. He acquired his Christian name Léonard (after Leonardo da Vinci) and created his own chapel in Reims, which he decorated with stained glass and frescos. While producing art with new themes such as Christianity and children, the artist also returned to painting the female nudes that had been his “signature style” in the 1920s. Fujita never commented on his war responsibility, but shortly before he died, he made an angry statement about how he had been treated immediately following the war.

It was wrong that I was born in Japan. Japanese are so jealous of me that they want to bully me. There are no other people like the Japanese, who conspire against me behind my back. They are all liars and people I cannot trust. How they have tortured me! I always thought to clarify myself at least once before I die. They owe me in that I helped them and have painted for them, but they have forgotten my kindness. They only think about themselves and are always trying to make money. There is no one as unhappy as I am. I am truly unhappy.25

As for Ogawara, he severed his ties with the major Japanese art communities in Tokyo, isolated himself in Kuchan, and kept silent about his war art until he publicly engaged the issue in the 1970s:

I was interested in surrealism but I gradually moved away from it. All the things that surrounded me became huge social pressures that moved in one direction and against my will. Those who resisted the pressure in that society were truly strong individuals who deserve respect. Unfortunately, I chose the path of conformity and I saw many people like myself. I also saw how those who followed the dominant power skillfully changed their opinions and positions after the war. Thinking about these experiences makes me emotional.26

Although the two artists continued to paint, during their lifetimes they never again received as much public attention as they had in the prewar and wartime period.

The Fujita Tsuguharu Resurrection in the 2000s

Fujita’s image has been greatly transformed in recent years in dramatic ways. This is partially due to the scholarship on wartime art that began in the 1990s following the death of the Shōwa Emperor in 1989, but the catalyst for the change in perception of Fujita’s war art in particular was the retrospective organized in 2006 by the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, two years before his exhibition in Hokkaido.27 In terms of the number of visitors, scholarly attention, and media support, the retrospective commemorating Fujita’s 120th birthday was a big success.28 With this retrospective, Fujita, who had previously been criticized as a war collaborator, was now “resurrected” as a great modernist artist.29 The retrospective was exceptional in many ways: it gained official support from Fujita’s widow Kimiyo, who had not always encouraged exhibitions of his work in Japan, it was the largest exhibition of his work held in Japan in the postwar period, and it displayed five war paintings by Fujita that the museum had rarely displayed to the public. What was especially remarkable was how the wartime paintings were represented. Fujita’s war paintings, especially his Attu painting, were explained as his effort to expose the “terrible realities of the war,” rather than to support the war effort. Many Japanese art critics echoed this apologist—and utterly implausible— interpretation of the paintings. Natsubori Masahiro argued that Fujita’s propaganda paintings do not display militaristic tones, and Kikuhata Mokuma stated, “where can we see propaganda effects in this painting that portrays the death of our comrades?”30 Nomiyama Gyōji even further vaguely contended, “his works are rather anti-war (hansen teki).”31 This newly constructed narrative of an “anti-war” Fujita transformed the painter into a tragic figure who was misunderstood and made a scapegoat over the issue of artists’ war responsibility.

Crucial to this re-interpretation of Fujita’s life and wartime art was his prewar success in France. Fujita was friends with internationally acclaimed avant-garde artists and his art was recognized in Paris, the artistic capital of the time. The museum, however, did not investigate why such an important artist had been ignored and forgotten by the Japanese public and art historians. Furthermore, instead of highlighting the transnational aspects of international modernism, the exhibition curiously recuperated Fujita as a “Japanese” artist and made his success a story of national glory. Ozaki Masaaki, the curator of the National Museum, wrote in English, “Having taken pride in being Japanese until then, the decision to sever ties with Japan must have been a painful choice for Fujita…He wanted to compete in the world as Japanese. That wish was irrelevant to his new nationality. Even if he resided in France and led life as a Frenchman, at heart, he was Japanese.”32 Reclaiming him as “Japanese,” the exhibition narrated his life in parallel with Japanese modern history. Ozaki wrote, “The process of Japan succeeding in modernization and being ruined for announcing its hegemony over Asia corresponds with the process of Fujita succeeding in Paris and eventually getting dragged into the storm of Japanese nationalism.”33 The celebration of Fujita’s fame was not only an art historical reevaluation of an individual artist, it was a historical reevaluation of a nation as well. The museum narrated both Fujita’s life and Japan’s modern history in such a way as to highlight their innocence and passivity in being “ dragged” into the war. By focusing on this victimization, the exhibition silenced the questions of both Japan’s national and Fujita’s personal war responsibility.

It was this image of Fujita as a pioneering avant-garde pacifist artist that the 2008 Hokkaido exhibition was built on. This exhibition did not display his war paintings, but instead focused on his large panel paintings produced in the 1920s. The four monumental panels—Composition with Lions, Composition with Dogs, Battle I, and Battle II (Raion no iru kōzu, Inu no iru kōzu, Tōsō I, Tōsō II)—were featured as “Fujita’s works that have never been exhibited in Japan before.”34 They were all painted in 1929 but were missing until discovered in storage outside Paris in 1992.35 In 2000, the panels were designated as French national heritage items, and the French government and the Hokkaido Museum of Modern Art collaborated on their restoration for this exhibition.36 The sheer number of curators and institutions involved in the project attests to both countries’ interest in Fujita. Aside from this grand international collaboration, what was notable was the way Fujita’s persona was transformed—yet again.

The exhibition emphasized Fujita’s interest in monumental works and religious themes, explicitly comparing him with Italian Renaissance artists. In the catalogue written in Japanese and French, French museum curator Anne Le Diberder compared his prewar Battle panels with Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel and called Fujita’s artistic exploration, “another story of the Renaissance.”37 Half of the exhibition space was dedicated to Fujita’s postwar religious works, including Crucifixion (1960), in which the artist painted the lean bodies of Jesus Christ and two others nailed to a wooden cross against the background of an ancient city under blue sky. His chapel, named “Notre Dame de la Paix,” which features stained glass with skeleton motifs, was said to refer to the tragedies of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, therefore symbolizing peace.38 In this familiar trope of peace and Hiroshima, Fujita himself was represented as standing for peace in a most peculiar way: the catalogue concluded, “‘Notre Dame de la Paix’ reminds us of his Japanese name, Tsuguharu, which means ‘the one who inherits peace.’ His name will forever pass on the message of peace brought to us by a dove.”39 Overall, by reworking the image of Fujita created by the 2006 exhibition, which had presented him as an avant-gardist, the 2008 exhibition made him into a Renaissance humanist. Step by step, through these two solo exhibitions, the formerly denounced Japanese artist Fujita Tsuguharu acquired the new identity he had wished for decades earlier. He became Léonard Foujita, the Japanese Leonardo da Vinci and—although he never sought this—a man of peace.

War and Modernism

While Fujita is over-celebrated as a national hero and Ogawara is marginalized as “Hokkaido’s local artist,” I suggest that their works are equally significant in understanding the relationship between prewar modernism and the war. The key to this investigation is Fujita’s Battle I and II (1928), the featured works in the 2008 exhibition. In this peculiar set of panels, the Caucasian men and women depicted are all naked for no apparent reason. The men are massively muscular and the women’s bodies are plump compared to the naked women in Nude with Tapestry. One to three individuals act in a group, and there are men and women violently wrestling with dogs, having conversations, and lying down. Fujita produced separate sketches for different parts of the panels and simply put them together on the canvas, which resulted in the “obvious lack of logic in composition,” as Le Diberder put it.40 According to Le Diberder Fujita drew on his studies of Greek and Renaissance sculptures at the Louvre Museum for the panels. She also suggests that Fujita’s interest in the classics was inspired by the neo-classicism of Andre Derain and Picasso in the late 1920s, whom Fujita knew in person.41 What Le Diberder does not mention is the possible connection between modernist neo-classicism in the late 1920s and fascist classicism of the 1930s and 1940s in Italy and Germany, which recent scholars of interwar European art have begun most often in the case of Giorgio de Chirico.42 If scholars including Alan Tansman, Harry Harootunian, Leslie Pincus, and Andrew Gordon point to the possibility of talking about “Japanese fascism,” inquiring into Fujita’s “classical turn” in the late 1920s is crucial, especially because the Battle panels seem like a significant segue to his Attu painting.43 The artist’s interests in the physicality of male bodies engaged in combat and the massive group portrait apparent in the Battle are pursued further in his Attu painting. The “obvious lack of logic in composition” in the Battle is successfully resolved in Attu, where dozens of soldiers are intricately interwoven and tightly engaged with one another in such a way that the dynamics of composition remain coherent. Is Fujita’s modernist “classical turn” in late 1920s Paris in any way related to fascism? If so, how does it anticipate his later works in wartime Japan that some scholars call fascist?

The works of Ogawara, who started out as a surrealist and was later transformed into a war painter again pose a question about war and modernism. The ambiguous political position of surrealism is expressed in the scholarship of art historian John Clark. On the one hand, he emphasizes the revolutionary spirit and potentially subversive nature of Japanese surrealism. He writes, “surrealists were simply the last recalcitrants in the art world against a tacit or explicit acceptance of ultra-nationalism.”44 On the other hand, he acknowledges, “the late-nineteenth-century and early-twentieth-century art world [in Japan] became modern without modernist art forms” (emphasis original), alluding to the fact that Japanese modern artists did not quite challenge the establishment in the political sense.45 Indeed, Ogawara was not the only surrealist who painted propaganda. Whether “coerced” or not, his mentor Fukuzawa Ichirō produced a war painting in 1945, which is included in the above mentioned war art collection at the National Museum. The problem also arises from the fact that surrealism reached its pinnacle in the late 1930s under supposedly tight militarist control, and as we have seen, Ogawara could present his surrealist work as late as 1940. In fact, art critic Moriguchi Tari in 1943 stated that despite the suspicion of militarists, Japanese surrealists are not anti-nationalists.46 In other words, the cases of both Fujita and Ogawara bring into question the conventional narrative that modernism disappeared when militarism emerged until after 1945. After all, almost all war artists were prewar modernists. We are now faced with different kinds of questions: why is it that so many modernists could become war artists with little trouble and ideological conflict? What is the relationship between modernism and nationalism in Japan’s case? Further scholarship on Japanese war art needs to elucidate this complex interplay of modernism, nationalism, and the war, as in the works of Fujita and Ogawara.

Asato Ikeda ([email protected]) is a Ph.D. Candidate in the Department of Art History, Visual Art and Theory at the University of British Columbia. Her dissertation examines Japanese art during the Fifteen-Year War (1931-1945) and the question of Japanese fascism. She is co-editor, with Ming Tiampo and Aya Louisa McDonald, of an anthology on Japanese war art, which will be the first anthology on the subject in English (forthcoming from Brill Academic Publishers). She is also currently serving Japan Art History Forum as the elected graduate student representative of 2010.

Recommended citation: Asato Ikeda, “Twentieth Century Japanese Art and the Wartime State: Reassessing the Art of Ogawara Shū and Fujita Tsuguharu,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 43-2-10, October 25, 2010.

Notes

I would like to thank Mr. Yabuki Toshio, the director at the Ogawara Shu Museum of Art, for sharing with me his valuable stories on the artist. This essay is indebted to Joshua S. Mostow, John O’Brian, Sharalyn Orbaugh, Ming Tiampo, Laura Hein, and Mark Selden who gave me valuable comments and encouragement. This essay also benefited from the editorial assistance of N. J. Hall and Ben Whaley. This is an edited version of my paper presented at the 12th Annual Harvard East Asia Society Graduate Student Conference, February 2009.

Please follow the links to other websites in order to view Fujita’s works.

1 Ara Masato et al., “Zadankai: sensō sekinin wo kataru,” Kindai bungaku, 1956. Maruyama Masao, Thought and Behavior in Modern Japanese Politics, ed. Ivan Morris (London: Oxford University Press, 1969), 10.

2 For more on the worldwide comparison of war art, see Laura Brandon, Art & War (London: I.B. Tauris, 2006).

3 “Ushinawareta sensō kaiga: nijūnenkan beikoku ni kakusarete ita taiheiyō sensō meiga no zenyō” [Lost War Paintings: The Whole Story of the Pacific War Art Masterpieces That Were Hidden in the United States For Twenty Years], Shūkan Yomiuri, August 18, 1967,

4 For a discussion of the collection and the controversy over its seizure and return, see Asato Ikeda, “Japan’s Haunting War Art: Contested War Memories and Art Museums,” disClosure: A Journal of Social Theory, vol. 18 (April 2009): 5-32.

5 Sawaragi Noi, Bakushin chi no geijutsu/ The Art of Ground Zero 1999-2001 (Tokyo: Shobun sha, 2002), 390.

6 “Samayoeru sensō-ga” [Hovering War Paintings], NHK, 16 August 2003.

7 Kay Itoi and George Wehrfritz, “Japan’s Art of War: A Show of WWII Propaganda Paintings Confronts the Past,” NEWSWEEK, 4 September 2000.

8 Léonard Foujita, exh. cat. (Sapporo: The Hokkaido Museum of Modern Art, 2008). After Sapporo, the exhibition toured Tochigi, Tokyo, Fukuoka, and Miyagi.

9 Shinmyō Hidehito, Ogawara Shū: Harukanaru imāju [Ogawara Shū: Distant Images] (Sapporo: Hokkaido Newspaper, 1995).

Recent discussion on Fujita refers to the remarkable increase in the number of publications and exhibitions on Fujita in the late 2000s. Examples include: Fujita Tsuguharu Exhibition (Tokyo: Oida Gallery: 2006); Paris du monde entire: Artistes étrangers à Paris 1900-2005 (Tokyo: The National Art Center, 2007); Masterpieces from the Pola Museum of Art: Impressionism and Ècole de Paris (Yokohama: Yokohama Museum of Art, 2010); Eureka: Poetry and Criticism (May 2006); Geijutsu shinchō (April 2006); Serai (February 7, 2008). Yuhara Kanoko, Hayashi Yōko, and Kondō Fumito all published books on Fujita in the decade.

10 Fujita Tsuguharu, ”Atorie Mango,” Bura ippon: pari no yokogao, Bura ippon: pari no yokogao (Tokyo: Kodansha, 2005), 167.

11 Originally in Ogawara Shū, “Kyogōnaru kitai” [Ambitious Expectation], Hokkaido Newspaper, 15 July 1938. Reprint in Shinmyō Hidehito, Ogawara Shū, 145-147.

12 See the second chapter of Maki Kaneko’s “Art in the Service of the State: Artistic Production in Japan during the Asia-Pacific War,” Ph.D. diss. (University of East Anglia, 2006). Kaneko points out that the reform was not completely the “imposition” of government control over art; artists also requested protection from the state.

13 Kawata Akihisa, “Sensō-ga towa nanika” [What Is Sensō-ga?]. For more on Japanese official war art, see Geijutsu Shinchō, August 1995; Kawata Akihisa and Tan’o Yasunori, Imēji no nakano sensō: nisshin, nichiro sensō kara rēsen made [War in Images: From the Sino-Japanese War to the Cold War] (Tokyo:Iwanami, 1996); Hariu, Ichirō and Sawaragi Noi, et al. Sensō to bijutsu 1937-1945/ Art in Wartime Japan 1937-1945 (Tokyo: Kokusho kankōkai, 2007).

14 Akiyama Kunio, “Hon’nendo kirokuga nit suite” [On This Year’s Record Paintings], Bijutsu, May 1944, 2.

15 Yamanouchi Ichirō, “Sakusen kirokuga no ari kata” [How War Paintings Should Be], Bijutsu, May 1944, 2-5.

16 Mark H. Sandler, “The Living Artist: Matsumoto Shunsuke’s Reply to the State,” Art Journal 55.3 (Autumn, 1996): 74-82.

17 Quoted in Sandler, “The Living Artist,” 78.

18 John Clark, “Artistic Subjectivity in the Taisho and Early Showa Avant-Garde,” Japanese Art After 1945: Scream Against the Sky, ed. Alexandra Munroe (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1994), 48.

19 For artists who died on the battlefield, see Kuboshima Sei’ichirō, Mugonkan nōto [The Silence Museum Notebook] (Tokyo: Shūei sha, 2005).

20 Fujita Tsuguharu, “Sensōga ni tsuite” [On War Paintings], Shin bijutsu (February 1943): 2.

21 For more on how the American public was confounded by the suicidal act, see Life, 3 April 1944, 36.

22 For visual domination and aerial perspectives, see Kari Shepherdson-Scott, “Utopia/ Dystopia: Japan’s Image of the Manchurian Ideal,” Ph.D. diss. (Durham: Duke University, forthcoming).

23 Watashino naka no genfūkei I [The Real Landscape of Myself I], exh.cat. (Kuchan: Shu Ogawara Museum of Art, 2007).

5. Kondō Fumito. Fujita Tsuguharu: Ihōjin no shōgai (Tokyo: Kōdansha, 2006), 305-7.

24 Fujita Tsuguharu, “Gaka no ryōshin” [Artists’ Conscience], Asahi Newspaper, 25 October 1945.

25 Fujita Tsuguharu, Bura ippon : pari no yokogao (Tokyo : Kodansha, 2005), 250.

26 Quoted in Shinmyō Hidehito, Ogawara Shū, 104.

27 For examples of war art in the 1990s, see Kawata Akihisa and Tan’o Yasunori, Imēji no nakano sensō: nisshin, nichiro sensō kara rēsen made; Bert Winther-Tamaki, “Embodiment/Disembodiment: Japanese Painting during the Fifteen-Year War.” Monumenta Nipponica 52, no. 2 (Summer, 1997): 145-80.

28 In an email correspondence, curator of the National Museum Ozaki Masaaki informed me that 290,000 people visited the retrospective in Tokyo, 220,000 in Kyoto, and 80,000 in Hiroshima.

29 Link. For a more detailed examination of this exhibition, see Asato Ikeda, “Fujita Tsuguharu Retrospective 2006: Resurrection of a Former Official War Painter,” Josai University Review of Japanese Culture and Society, vol. 21 (December 2009): 97-115.

30 Natsubori Masahiro, Fujita Tsuguharu geijutsu shiron [The Art Theory of Fujita Tsuguharu](Tokyo: Miyoshi kikaku, 2004), 339; Kikuhata Mokuma, Ekaki ga kataru kindai bijutsu [Modern Art Examined By a Painter] (Fukuoka: Genshobō, 2003), 228.

31 Nomiyama Gyōji, “Boku no shitteru Fujita” [Fujita That I Know], Eureka: Poetry and Criticism (May 2006), 63.

32 Ozaki Masaaki, “On Tsuguharu Leonard Foujita,” trans. Kikuko Ogawa, Leonard Foujita, exh. cat. (Tokyo: The National Museum of Modern Art Tokyo, 2006), 191. This is an example of what art historian Bert Winther-Tamaki has called “artistic nationalism,” in which international influences and hybrid cultures are ultimately subsumed by the paradigm of nationalism. Bert Winther-Tamaki, Art in the Encounter of Nations: Japanese and American Artists in the Early Postwar Years (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2001).

33 Ozaki Masaaki, “On Tsuguharu Leonard Foujita,” 190.

34 From the exhibition website (accessed on December 15, 2008).

35 The Panels are now owned by the General Council of Essonne.

36 Léonard Foujita, exh. cat. (Sapporo: The Hokkaido Museum of Modern Art, 2008), 12-7.

37 Anne Le Diberder, “Battle and Composition: Fujita’s Unreleased Works”; “Another Story of Renaissance,” Léonard Foujit, exh. cat. (Sapporo: The Hokkaido Museum of Modern Art, 2008), 72; 84

38 This Hiroshima connection was a new element added to the Fujita narrative. It was not Fujita but rather the President of the Pen Club Yves Gandon who made the reference to Hiroshima in his speech at the opening of the chapel. Léonard Foujita. exh. cat. (Sapporo: The Hokkaido Museum of Modern Art, 2008), 174; 203.

39 Léonard Foujita. exh. cat. (Sapporo: The Hokkaido Museum of Modern Art, 2008), 203. As far as I researched, Fujita’s Chinese characters 嗣治 do not refer to peace.

40 Léonard Foujita. exh. cat. (Sapporo: The Hokkaido Museum of Modern Art, 2008), 73.

41 Léonard Foujita. exh. cat. (Sapporo: The Hokkaido Museum of Modern Art, 2008), 81.

42 Emily Braun, “Political Rhetoric and Poetic Irony: The Uses of Classicism in the Art of Fascist Italy,” On Classic Ground: Picasso, Léger, de Chirico and the New Classicism 1910-1930 (London: Tate Gallery, 1990).

43 Alan Tansman, The Aesthetics of Japanese Fascism, 1st ed. (University of California Press, 2009); Harry Harootunian, Overcome by Modernity: History, Culture, and Community in Interwar Japan (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001); Leslie Pincus, Authenticating Culture in Imperial Japan: Kuki Shūzō and the Rise of National Aesthetics (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996); Andrew Gordon, Labor and Imperial Democracy in Prewar Japan (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992).

44 John Clark, “Surrealism in Japan,” Surrealism: Revolution by Night. exh.cat. (Canberra, National Gallery of Australia, 1993), 209.

45 Clark, “Surrealism in Japan,” 204.

46 Moriguchi Tari, Bijutsu gojūsshūnen (Tokyo: Masu shobō, 1943), 532.