Introduction

As a fellow Tokyoite once observed, Hokkaido people have a knack for interesting self-introductions. It’s surely in part because everyone other than the indigenous Ainu came rather recently from elsewhere, and even people in late youth and early middle age are apt to be in touch with that history of migration: of the adventures and misadventures of grandparents and great-grandparents in the throes of rapid settlement (often with corresponding displacement), industrializing agriculture and fishery, global trade, imperial expansion (“Karafuto” still coming up more often in conversation than “Sakhalin”), accompanied by requisite academic investments in fields such as agronomy, foreign language, economics, and cultural production as well as, of course, movements of resistance to the same.

It was at a ladies luncheon in Otaru, the leading military and commercial port in Hokkaido in the early twentieth century, that I first met Sonoda Mineko. “Ladies luncheon” is a stopgap translation for joshi kai, a term disliked by some women for the same reason that a generation of us objected to the use of “girls” to refer to adult women, whether 25 or 85. Maybe, though, the reader might imagine the capaciousness of the joshi kai genre by visualizing ten or so Hokkaido women in their seventh and eighth and even ninth decades surrounding a table laden with deliciousness, drawn together in animated speaking and generous listening, warmed by the midday sun of a northern winter streaming in through the windows of Atorie Kurēru.

|

“Ladies Luncheon”: Sonoda is in far back in white sweater Courtesy Takahashi Akiko, Atelier Claire |

The date was February 21, 2013, the relaxed day after the annual observation of the death by police torture of proletarian writer Kobayashi Takiji (1903-33) of “Crab Cannery Ship”1 fame on the snowy slopes of the municipal cemetery of his hometown. Most everybody at the luncheon had braved the graveside gathering or attended the evening program of music, readings, and lecture. “Atelier Claire” is a space for exhibitions, poetry readings, Article 9 meetings, film screenings, and a stray-cat clearinghouse. The last is a constant feature, so much so that the Atelier is also called Neko-no-jimusho, the “office-for-cats.” It is also the home of Takahashi Akiko, who used her retirement funds from Hokkaido Electric Power Company to construct “Claire.” There, where she felt her rights as a worker protected by “democratic unionism,”2 she opposed the construction of Hokkaido’s sole nuclear power generating station at Tomari from its planning stages on, an orientation shared by most, if not all, of the luncheon attendees.

The sole former schoolteacher at the luncheon, Sonoda Mineko, was more eager listener than speaker. It was well after we had disbanded that she called my friend who had organized the event. We were driving in the dark winter night when Sonoda asked my friend to relay something to me. Why not tell her yourself, she said. Sonoda was apologetic, as if for an intrusion. “There’re just a few things I didn’t mention. How I began to see what home economics could be in that mining town. It was actually important for the students to learn about nutrition. And I wanted them to realize that their own tastes mattered, quite apart from what was fashionable.”

I had recently seen Doi Toshikuni’s 2010 documentary, “Watashi” o ikiru (Living “Who I Am”), featuring three educators—an elementary school music teacher, a middle school home economics teacher, and a high school principal—who had in common their opposition to the imposition of the Rising Sun flag and Kimigayo anthem in school ceremonies and the harsh disciplinary actions adopted by the Tokyo Metropolitan school district to enforce it. It was in the late 1990s that the Education Ministry began a stringent campaign to enforce observation of the flag and anthem; in 1996, the “national flag and national anthem law” went into effect. These measures not only effectively constituted a final blow against dissent on the flag and anthem because they suggested continuity with the prewar regime but stifled widespread experiments with graduation ceremonies, such as the “circle style” in which all participants would be on floor level. In the case of Nezu Kimiko, the home ec teacher, the camera not only followed her lonely protests on graduation day against the flag and anthem outside the gates of the school from which she had been banished, but let us imagine her classroom presence through glimpses of her syllabi—units on cooking that were as much challenging exercises in chemistry and social studies as in culinary instruction.

|

“‘Watashi’ o ikiru”flyer. Nezu Kimiko, the home ec teacher, is pictured on the left |

That was the first time I had ever imagined “what home economics could be,” in any setting whatsoever.3 Sonoda Mineko’s postscript of a telephone call recalled and recharged that sensation. Nearly three years later, when I reminded her of that telephone call, she couldn’t remember what she had said. But you were talking about housing and the value of students’ becoming aware of their own taste, I insisted. “Well, yes, I suppose so. I was always interested in housing. Students need to know housing is a human right! It’s not something they can do anything about right away, but I wanted them to know how to think about it, to have a point of view. I thought this would help them in future. It’s a great topic for essay assignments.”

Sonoda’s telephoned after-thought, delivered diffidently but with the unmistakable energy of conviction, conveyed a mission for home economics, one claimed by several generations of teachers in Japan. Before continuing with her story, therefore, let me say a word about the history of home economics education (kateika kyōiku) in Japan. Education in any society develops in response to multiple needs. Along with changing notions about the child and the individual, state and capital are inevitably instrumental in shaping the form and content of education. Home economics has distinctive appeal as a vehicle for inculcating gendered (womanly) skills and a corresponding identity. Two decades into the Meiji Period, instruction for girls in sewing and housework combined with “ethics for girls” (joshi shūshin) to undergird the ideology of “good wife, wise mother” in service of the state.

A dramatic, indeed, utopian transformation was signaled in 1947, two years after the end of WWII, in the Education Ministry curricular guidelines mandated home economics for both boys and girls in elementary and middle school. Girls and boys were to be prepared to participate in the creation of a democratic household, in accordance with the principles of basic human rights, respect for the individual, and gender equality as proclaimed in the new Constitution. The means for implementation of these principles were elaborated in the Fundamental Law of Education.4

In practice, however, home economics as educational preparation for a democratic household in a democratic society has been constantly subject to manipulation, notably in middle and high school, in the interests of ideology (moral education) or labor needs as conceived by business and government. Girls were steered toward home economics, construed as training for maintenance of the home, in turn understood as the site for labor reproduction that provided nourishment, child education, relaxation, and increasingly, elder care.5 As a corresponding course of study, boys took classes in “industrial arts” (gijutsu). Such tendencies were boosted by events such as the “Sputnik shock” of 1957, when the former Soviet Union succeeded in launching a satellite: boys were deprived of a chance to study home economics and girls, “industrial arts.”6 Eventually—three decades later—middle school boys and girls would be taking courses combining the two areas.7

It’s important to note, however, that there has been not only spirited resistance to the backsliding but efforts to more fully realize the hard-won postwar vision of 1947. Pressure from the United Nations was also crucial. Although initially reluctant to ratify the Convention on Discrimination Against Women and the Status of Women (CEDAW), the Japanese government eventually reversed itself, which entailed among other measures the curricular reform of home economics whereby it became mandatory for boys as well as girls, at the middle school level in 1993, high school in 1994.8

What does the future hold? The Fundamental Law of Education was revised in 2007, ominously tilting toward emphasis on Japaneseness and love of homeland and away from individual autonomy.9 Article 9, the so-called no-war clause, is still on the books but has truly been eviscerated by the passage of the “security-related legislation” on September 19, 2015.10 Most worrisome is the proclamation of the legitimacy of “collective self-defense,” whereby if, let us say, a US naval warship found itself threatened by the Chinese navy in the South China Sea, Japan could legitimately set forth in defense of its ally, in other words, in a situation in which Japan itself was not directly threatened.11 This is revision of Article 9 through the back door, say an overwhelming majority of scholars of the Constitution and bar associations. But it is not only Article 9 that is under threat today. The assault against Article 24 of the Constitution, on gender equality, is not as well known but intensely dismaying and all the more menacing with the meteoric rise of the Nippon Kaigi, a broad-based political organization seeking Constitutional revision, the restoration of the emperor to his rightful position, the promotion of patriotic values, etc.—a menu irresistible to local and national conservative politicians, including half of the current cabinet, with Prime Minister Abe himself serving as “special adviser.”12

Sonoda Mineko’s formation as a home economics teacher in a declining mining town in Hokkaido condenses a chapter of postwar Japanese history: of star-reaching aspirations for a reborn, democratic Japan, whose Constitution pledged commitment not only to the principles of pacifism, but to other substantive requirements of democracy such as gender equality and a “wholesome and cultured living.” Education was a principal battleground for the actualization of these principles, and teachers’ unions a prominent vehicle for this struggle. What we learn from Sonoda’s story is how crucial union activities, and collective endeavor in general—such as the work of national organizations with local branches dedicated to the exploration of the theory and practice of democratizing education as pertinent to various disciplines—were to not just the self-evidently political struggles of the day, but to weaving the fabric of a democratic society. And home economics, of all subjects, was essential to this struggle because it entailed gender identities fundamental to the character of any society. Perhaps because “home economics” seems inherently bound up in a restrictive, retrograde understanding of women and girls, compounding its ostensibly nonintellectual basis in daily life, its possibilities as a discipline in schools and a subject of study for researchers has been forgotten. This appears to be the case in the U.S. as well, as my brief reference, above, to the example of the University of Chicago, suggests. Sonoda’s story is arresting not only as testimony to the progressive possibilities of home economics, but as a reminder of the power of group endeavor in the pursuit of postwar aspirations for democracy, the power as well of collective endeavor in promoting individual flourishing that most of us not only have not experienced but cannot imagine. Defeat in war allowed for the recognition that a democratic household, the democratic education of individual citizens with rights, and a democratic, peaceful society were mutually constitutive. Such recognition is as priceless today as it was nearly 70 years ago. Take, for example the world depicted in Andrea Arai’s The Strange Child: Education and the Psychology of Patriotism in Recessionary Japan (Stanford U.P., 2016), in which “the child” has been made the symbol of social dislocation and the target of corrective measures having little to do with familiar kinds of hard work yielding credentials and leading to employment. Anxious, not to say frantic, parents and tired teachers struggle alone, under scrutiny. Union activity as a site of protection and pursuit of the principles of democratic education to benefit students as well as teachers has become, at best, a remote memory for most educators.

If the foundations of Sonoda’s experience in Hokkaido seem too specific to resonate for many, let us be mindful of how a peripheral region can crystallize the contradictions of modernizing Japan, helping to make visible developments appearing in subtler form elsewhere. The national shift in energy policy from coal to oil is the setting for Sonoda’s coming-of-age, as a teacher, a woman, a political being. Born in 1932, she retired in 1993, the year before home economics became mandatory for high-school boys as well as girls. Her worldview changed dramatically over the course of three decades of teaching. Indeed, it was hardly predictable that she would have ended up teaching at all, especially home economics: “I looked down on women, and I looked down on home economics. It’s because of the kind of family I was raised in.” What follows is her journey as reconstructed from extended conversation.

Sonoda Mineko’s Story

Part I (June 27, 2014)

Childhood, the World of “Massan,” and Yoichi High School

NF Why don’t we start by your telling me something about your family?

SM You want to go that far back? All right. My grandfather was from Kagoshima, Shimazu domain. He revered Saigō Takamori and fought on his side in the Seinan War. After they were defeated, my grandfather fled to Hokkaido. Even when he got to Hokkaido, he kept heading north until he ended up in Kitami Mombetsu (on the Sea of Okhotsk). He found work with a fishery boss who controlled the eastern coast of Hokkaido from Kushiro on up. He tried his hand at shop keeping at some point, but his highhanded samurai mentality got in the way of dealing with customers. He did well enough, though, eventually owning an inn and a cattle farm. He even served as an elected member of the village council. When two of his older children got tuberculosis, he was able to send them to Honshu to recuperate. He died when my father, born in 1906, was 12. My grandmother had already died when he was 9.

My father went to Ikubunkan Middle School in Tokyo and from there to Meiji University.

NF Your grandfather must have left something of a fortune to make that possible!

SM No, it was my aunt, his older sister. She’d had to marry somebody she didn’t want to. He was a notorious Scrooge. If somebody he’d loaned money to couldn’t pay up because of illness, he’d strip the covers off that poor soul. That was his reputation, anyway. My aunt had gone to Hokusei Girls’ Higher School and become a Christian. Of course, she didn’t want to marry this guy, but my grandfather said, with two of your siblings having TB, there isn’t going to be anyone else willing to marry you. So they took over my grandfather’s inn. And whenever she could, Auntie would secretly send money to my father studying in Tokyo.

When we kids, my brother and I, fought over food during the war, Dad would scold us saying that when he was a student and Auntie couldn’t send him any money, he’d survive on water for the whole day. He had a live-in arrangement with one of his rich classmates, working as a houseboy (shosei). He got his breakfast and dinner from the family, but no lunch. I can understand that it must have been hard on him to be dependent on a classmate’s family, where the father belonged to the peerage.

He was a hard worker, my father. His older brother went to Chūō University, graduating from the law department, I think. He did quite well. But when my father graduated with a business degree in 1930, there were no jobs waiting for him. He lived upstairs in his brother’s house. That’s where he started married life with my mother.

Mother’s side of the family came from Kagawa. Her father was the oldest son from a not wealthy family, but he ran off with the daughter of a well-to-do family in the salt business. They took off for Hokkaido, where her family couldn’t track her down. Mother was the youngest of six, born in 1912. She got together with my father because she had a Christian older sister who was friends with Dad’s Christian sister. Mother yearned for Tokyo. She loved literature. She was so excited to be going to Tokyo, to marry a university graduate! She promised her sisters she would send them copies of Central Review (Chūō Kōron) when she was finished with them. But Dad turned out to be the kind of guy who liked the detective fiction in New Youth (Shinseinen). Mother was so embarrassed she couldn’t bring herself to tell her sisters.

Her first summer in Tokyo, the upstairs room at her brother-in-law’s was so hot that all she could do was walk around outside. Then she became pregnant with me. They had to think what to do next. There was a little rental house next to the inn that Auntie ran with her husband. So they moved back to Hokkaido and into that house. I was born in Mombetsu in 1932. Dad was told he could either become a middle school teacher or work in the tax office. No way he was going to teach, he said. So he joined the tax office, first in Nayoro, then Asahikawa, then Sapporo. He was in charge of liquor taxes. He’d dress up like a farmer and go after bootleggers. But farmers could see right through his disguise. There were stories going around that they’d heave inspectors over cliffs, killing or at least maiming them. Mother was always worried until Dad came home. Even though he was careful to cover his head and face.

|

Cities and towns in Hokkaido appearing in Sonoda Mineko’s story |

But that wasn’t all. As the kids kept coming, they didn’t like the thought that we’d be changing schools every two years. A distant relative had a steamship company in Otaru, so off we went. She turned out to be a harsh employer, and Dad didn’t want to stay on. One day, he up and announced that he was going to work for Nikka Whiskey. So our family got on the train and moved to Yoichi, the town next to Otaru.

|

Nikka Whiskey Yoichi Distillery Main Gate |

There’s going to be an NHK drama (Massan) about the president of Nikka and his Scottish wife Rita-san. I was interviewed for it because I was their adopted daughter’s playmate. A few years ago, I wrote up my experiences from those days in Yoichi Arts.13 I was sickly back then. I missed so much school. There weren’t any drugs yet for treating TB. Taketsuru Rita-san would make delicious soup and have it delivered to my house. I enjoyed many wonderful foods at their house, but I can’t remember what they were now. I should have gone to girls’ higher school during the war, but I couldn’t pass the physical. I was sent to the Red Cross hospital in Kitami instead. When the war ended, I entered the Yoichi Girls’ Higher School, which was soon consolidated with the formerly male middle school. That was my first experience of coeducation. I graduated in 1952.

NF What did you do then?

SM What could I do! Even though my father worked at Nikka, he wasn’t well paid. Mother took in piecework, and I tried to help her. Banks were where people most wanted to work. I thought working at a bank would be good, too. I wanted to be somewhere mainstream. But because my father was in the accounting department at Nikka, he didn’t want me going anywhere where he had dealings. There was only one company in Yoichi with publicly traded stock. It was a mining company. They’d refined manganese for weapons. But after the war, there was no need for weapons, and they were in the red. My father asked them to give me a job. They probably couldn’t say no to him. But once I started working there, I realized there was nothing for me to do. I was crushed. What did I do for eight hours? Sorted the mail. Went to the bank. Served tea. The head of the office said I could do anything I wanted if there was nothing to do. So I brought my knitting. “Do anything but knit,” he pleaded. “It’ll look bad to visitors.” So I read instead. One year later, there was a fire, and the company burnt down and declared bankruptcy. I got unemployment.

NF What did you decide to do then?

SM Well, one of my Yoichi High School teachers contacted me. A male library assistant was moving on to technical school. I had been on the library committee when I was a student. Was I interested in becoming an apprentice assistant?

The teacher actually came to our house to ask my father’s permission for me to take this position. Father told me later that his concern was I’d miss my chance to get married. There were so many of us kids. You have to get married within three years, he told me.

It was 1954 when I took on this apprenticeship. I was the youngest person on the staff. Remember, everybody there had been my teacher. I was saying “yes” to everything, everybody, all the time.

Three years went by and no marriage prospects turned up.

NF What next?

SM A new person joined the library staff. A college graduate. He was younger in age but senior to me. I didn’t have the right to attend faculty meetings. But he did. And he’d send me out to buy cigarettes and lunch for him. I gritted my teeth and didn’t say anything. I didn’t want them saying I was cheeky, that that’s why I was a marriage market “leftover.”

So I decided to earn some qualifications myself. I knew someone who had gotten teaching credentials through testing, without having gone to college. I thought about enrolling in a correspondence course. That would take four years.

Now, the biggest part of my job was sorting out the books in the library during summer vacation. But that’s precisely when schooling14 takes place for correspondence course students. I didn’t think my supervisor would allow it.

There were several schools I considered, like Keio and Nihon Joshidai (Japan Women’s University). I decided on Nihon Joshidai.15

Women Aren’t So Stupid! Correspondence and “Schooling” at Japan Women’s University

NF How did you make that decision?

SM While I was thinking about all this, one of my former teachers said, by the time you’re done, you’ll be thirty. No way you can compete with a male teacher. But you might make it in home economics.

I detested home ec. When I was in high school, it was taught by the language (kokugo) teacher, who didn’t know a thing. She just read out loud from a book: [when washing] “parenthesis: turn the pockets inside out.” Can you imagine?! Reading “parenthesis” out loud! I was an awful student. I harassed the teachers. When we figured out a teacher didn’t know much about a subject, my friends and I would get together, do a little research, and ask questions we knew the teacher wouldn’t be able to answer.

So I didn’t just look down on home economics. I didn’t think too highly of teachers in general, and I didn’t want to go into teaching. Nihon Joshidai had a food science course. I thought I could become a nutritionist if I enrolled in that program.

Then I learned that you needed two years of experience before you could enroll. So I resigned myself to becoming a home ec teacher. And I finally told my supervisor, the head of the library. I presented it as a fait accompli.

NF How did he take it?

SM He was furious! But looking back on it, maybe I should say he was more disappointed than angry. He was someone who inspired Ito Sei16 to become a writer. He used to say to us, “This is a college-level course. I don’t expect you to understand it.”

That was infuriating! But I learned many wonderful things from him. And he said, “All right, take four years. You can do this for four years.”

NF Did you get help from your family?

SM My brother who was two years younger had just started at Hokkaido University. There were other younger siblings. So no, I didn’t get any money from my family.

It was hard! I went to Tokyo by myself. It was late July, when the dorm rooms for the regular students became available. You had to bring your own bedding. There I was, with that heavy futon from Hokkaido! I stayed in the second floor of a wooden dormitory. It was so hot. I’d wake up and find that my body was molded into the futon from all the sweat. At first I thought I was getting sick. I was in for a series of surprises.

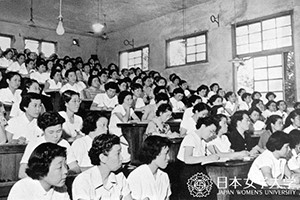

|

“Schooling” session for correspondence students at Japan Women’s University, 1953 |

First of all, to see how many women showed up in that heat for the entrance ceremony! That was 1958. There might have been about 300 women filling that auditorium. Their eyes were shining. They all wanted to study. I’d been educated to look down on women. My own family was conservative, so I’d absorbed that way of thinking. But it occurred to me then, maybe I’d been wrong to despise women!

Some of them were older, some younger than I was. I quickly realized how behind I was because of the education I’d gotten in Hokkaido. I was desperate to catch up. Only one-tenth of the enrollees would graduate.

The head of our dorm was an obāsan married to one of the silver-watch crew17 from Tokyo University. You had to kneel when you addressed her. There were several women assigned to each room, and you used “sama” in talking to each other. Nihon Joshidai thought of themselves as the authority on women’s education in Japan.

Many of my fellow students already had teaching jobs. They wanted to improve their credentials, for various reasons. There was someone from Niigata, an English teacher. She wanted to be qualified in other subjects so that she’d have some choice when she was being transferred.

She’d graduated from Aoyama Gakuin Jr. College.18 I was especially behind in English. The teachers I’d had in high school didn’t amount to much. Not that you could blame them. They’d hardly had a chance to study anything during the war. My friend from Niigata would spend whole days helping me catch up. The teacher of the course, Shibazaki Sensei, was the head of the English program at NHK. She was a kind teacher, and her explanations were so easy to understand. It was a revelation to me! This was what studying English could be! Shibazaki Sensei was strict, though. I remember her saying to another student, “You couldn’t answer my questions yesterday, either. Are you really serious?” I began to lose my smart-alecky attitude toward teachers.

Seeing other students struggle was important for me. There was a mid-term and a final at the end, which covered the whole year. If you failed an exam, you had to go for another whole summer of “schooling.” You even had to pass gym. There was one woman who was in her 70s. There were students who’d been coming for 15 years as they worked or raised their families. That first summer, there was a woman who was always at the sink, washing away. There was something … disgusting about this. It turned out she had left a baby she was still nursing at home. She was expressing her milk with her hands. That was how much she wanted to study!

I began to see how lucky I was.

NF What do you mean?

SM I was just an apprentice assistant. I didn’t have to be doing curriculum research over the summer, like the ones who were already teachers. Working at a library meant I had access to all kinds of books. That came in handy for writing reports. Oh, you had to have your reports accepted before you were allowed to take the exams. I was always desperate when I had to write reports. The slapdash reports I turned in were always rejected! At the end of the third year, I was still missing quite a few credits needed for graduation. Remember, I was only given permission to take four years for this.

That last year, I never slept in my bed. I’d fall asleep studying in the kotatsu. For my science courses, I could get help from the teachers. And unlike the others who already had teaching jobs, I didn’t have daily course preparations on top of my own studies. I managed to graduate on time.

NF Were you going to stay in Yoichi?

SM Well, my parents had moved to Tokyo in 1959 for my father to head up the Nikka Whiskey plant in Tokyo. That was in Azabu, and there was company housing across the street, in what’s now Roppongi Hills! So after that first summer in the upstairs dorm room, I went to classes from my parents’ company housing. But when I was done, there were still five younger siblings. There was no room for me. I was told to go back and take care of the family home in Yoichi.

Teaching and Learning in Utashinai, a Mining Town in Decline

NF What about a job?

SM Well, all kinds of schools in Hokkaido began writing to me once word got out that I had finished the program at Japan Women’s University. Lots of girls chose the home ec track in high school in those days—like me, they knew they weren’t going to be sent to college—and there weren’t many qualified teachers yet. But I was picky. This school was too small, that one was in the boonies of Hokkaido. I thought I was better off staying at the school library in Yoichi. But my second year after graduation, my mentors told me I couldn’t go on acting so spoiled.

Then came a query from Utashinai High School. Well, Utashinai was a city at least, and it was in central Hokkaido. The principal even came out to Yoichi to try to talk me into coming out in July of 1963. I later realized he’d come to check me out.

I went out to Utashinai to see what it was like. I expected the high school to be a reasonably impressive building. 1962 was the year of the Petroleum Industry Law. The national energy policy was shifting from coal to petroleum, and coalmines were failing one after another. This had already happened in Kyushu. Hokkaido was next. A large mine in Utashinai had already gone bankrupt. The town felt desolate.19

There wasn’t even a gas burner for cooking at the school, just a portable clay pot. I went to a house that had a room for boarders like me that someone had recommended. The lady there said that a mining town was a nosy, fussy place. Don’t take the shortcut in front of the company row houses where everybody can watch you close up, she warned. Take the main road instead.

All the time I was growing up in Yoichi, my mother told me not to do anything that would hurt my father’s reputation. I’d hated feeling constrained like that and wanted to get away from that sort of thing.

I went back to Yoichi and told the school that I’d decided against moving to Utashinai. I wanted to stay on as apprentice library assistant. They said no, I couldn’t do that because the letter of appointment had already been issued. Stick it out for a year, they said, then we’ll send for you to come back.

So I ended up going. Because I was starting in the middle of the school year, I didn’t have homeroom responsibilities. The students were pretty obedient. But I hated the town. There was no life. I had an aunt living in Sapporo, and I visited her every weekend. The boarding room lady even thought I might have a boyfriend there. Over winter vacation, I went home to my parents’ in Azabu.

|

Utashinai High School, mid 1950s-1960s From “Manabi,” Utashinai City homepage |

At the end of vacation, I learned on the ferry back to Hakodate that there’d been a fire, and the house where I boarded had burnt down. I’d left most of my things there—the good suits, the bedding. Everything was gone. I announced that I was resigning and going back to Yoichi.

Then the head of the home ec department said, “Do you think we can find somebody who’s willing to replace you in January? Because you took your time deciding whether to come here, these students went without a teacher until July. Are you going to do this to them again?”

I said I would teach until the end of the school year in March. After that, I thought I’d head out to Tokyo.

The other teachers felt sorry for me for having lost everything in the fire. One home ec teacher undid her own sweater and re-knit the yarn into a sweater for me. Another took apart her skirt, turned the fabric inside out, and sewed it into a skirt tailored to my measurements. Everybody tried to help. I couldn’t quit in March any more!

NF What was your second year like?

SM Remember I said that the principal came all the way to Yoichi? I’d thought it was to try to talk me into taking the job. But he never asked me a single question about home economics. Instead, he asked me what I thought of unions. I told him I had no interest in them. Everybody he asked confirmed that I was telling the truth.

There was only one union then, Hokkyōso (the Hokkaido Teachers Union). High school teachers belonged to it alongside elementary and middle schoolteachers. But then a new union, just for high school teachers, was started up. Kōkyōso (Kōtōgakkō Kyōshokuin Kumiai, the High School Teachers Union) was like a company union. They lured us with flattery and pay raises: we high school teachers were better educated than elementary and middle school teachers. It was only appropriate for us to be paid more, they said. The high school union promised that we would be moved up one step each in rank with a salary increase, effective immediately. I come from a family that prided itself on its samurai descent. I joined without any sense of conflict. Everybody joined. Hokkyōso was quite radical, but this was going to be a quiet union, we were told.

We took turns attending the union meetings. I didn’t mind the little allowance that came with it—like the lunch fee. The meetings were unbearably boring. The union songs didn’t appeal to me at all. The leaders’ impassioned speeches left absolutely no impression. So when the principal from Utashinai asked what I thought of unions, I could say quite honestly that I wasn’t interested in the least.

NF What about your new colleagues in Utashinai?

SM There were a number of Communist Party members on the faculty. It was quite a progressive group, really. This principal used to be a member of Hokkyōso, so he knew all about it. He had made it his mission to crush progressive elements in the school. I was his first appointee. The other new teachers had come at the start of the new school year in April. They weren’t teachers that he had chosen. “You’re my first one,” he said.

The first issue at hand was the administration of ability testing (nōryoku kentei shiken) for high school students.20 This was all about ranking the students. The union was opposed. This test wasn’t going to benefit the students in any way. The principal was determined to administer it, and he called me in: “We’re going to do this test. We’re going to put it to the faculty. I want you to speak up in favor of it.”

I told him I’d listen to what everybody had to say, and if it seemed like a good idea, I’d speak up in favor of it.

Before I took the job at Utashinai High School, everybody told me, “Remember, the principal handpicked you for this position. Just get his advice about everything and go along with what he tells you.” I knew my mentors cared about me. They were looking out for me. We’d had several study sessions before I left.

Well, I listened to everybody at the all-faculty meeting. And the test just didn’t make sense to me. So I raised my hand—not many women spoke up—and said I was opposed.

Of course, I got called in. “Why did you go against me? Didn’t you realize you were biting the hand that feeds you!?”

I hadn’t understood that I was the principal’s lapdog. He’d been calling me into his office regularly. He’d ask about this teacher and that, mostly faculty engaging in union activities. That set me to wondering about this man. A school principal should be of good character! When I grasped that he thought of me as his servant … well, that was the beginning of another set of discoveries. I began to go to study sessions held by the union. And I joined actions—like International Anti-War Day, October 21. The biggest struggle was Ampo.21 I began to see that the conservative ideas I’d brought with me were wrong.

NF How about the students?

SM In Utashinai, the mines was the only employers. There wasn’t even a farmers’ union. All the students’ families were miners. It was a closed shop, and everybody belonged to the union. It was the kind of place where, when we teachers went on strike, the students would call out from the windows, “Sensei, gambare!”

|

High-school Avenue (Kōkō Dōri), which the students ascended and descended every day From “Yama no kioku, Kashin-chiku,” Utashinai City homepage |

It was in the course of making home visits that I really started to learn about the students. The families would tell me what their working conditions were like. The Japan Coal Miners Union (Nihon Tankō Rōdōsha Kumiai, or Tanrō) was tied in with the Japanese Socialist Party.22 If you became a union official, you didn’t have to dig any more. The parents told me that the officials were “mice with black heads”—they might look like miners, but they were arrogant and had power over you. If you opposed them in anything, they could move you to an unfavorable spot in the mine, where you weren’t going to harvest much coal.

I learned so much from the dads! The kids would say, you just keep talking to our dads. Not many high school teachers make home visits, so at first, the families would get worried when I showed up. They assumed their kids had done something wrong.

NF What made you go on home visits?

SM It’s something I learned about through circles organized by the Non-governmental Educational Research group (Minkan Kyōiku, Minkyō).23 We studied to see what we could do in “daily life guidance” (seikatsu shidō). I learned that if there were students who were floundering, you divide the class up into groups and put that student in with stronger ones. The emphasis was on everybody caring about the whole group. That would become the most important point for me throughout my years as a teacher.

Through area-specific workshops, we began to see that the home economics textbooks written in Tokyo weren’t helpful for students in Hokkaido, whether with respect to food or housing. Kakyōren, the home economics research group, was established in 1965 as a national organization, and a branch was set up in Hokkaido, too.24 I was urged to join and began to study with other members. We wanted to prepare teaching materials that would truly help students.

Through the correspondence course and schooling, the contempt I’d had for women—which included myself—was corrected. When I became a teacher, and then a union member, I awakened to more contradictions in my way of thinking. Kakyōren was vital to this process.

NF What kind of changes did you think were necessary?

SM Well, housing, for starts. You have to emphasize winter in Hokkaido. Many home ec teachers don’t like to teach about housing. They prefer clothing, for instance. But I found it fascinating. I’d be selected to attend many national study sessions. We did a lot of research and wrote reports. We gathered material from newspapers, too. Made comparisons with other countries. Collected books that we thought would be useful.

Minkyō was an umbrella group, and Kakyōren, Rekikyō (history teachers’ association), and Seikatsu Shidō Kenkyū (daily life guidance research) were all part of it. If the union could get funds for two or three of us to go to a meeting, we’d pool the funds together so more of us could go.25 If we were going somewhere where we knew other teachers, we’d stay at their homes and save money. If it was a place like Lake Tōya, we’d pitch a tent!

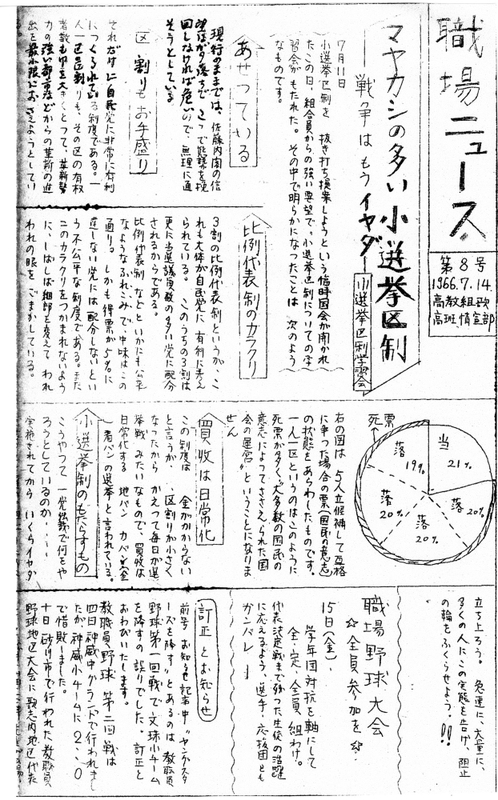

NF Shokuba nyūsu (Workplace News), the union paper of Utashinai High School, gives a good deal of coverage to the issue of in-service training generated by teachers themselves rather than the Education Ministry. I can see the teachers put a lot of energy into securing and sustaining the workshops they felt they needed, which also meant not being coerced into attending Ministry workshops. You worked on that newspaper, didn’t you? It looks like a weekly. That must have been a lot of work, on top of everything else you had to do.

|

Shokuba Nyūsu (No. 8, July 14, 1966). “Only Smoke and Mirrors: The Single Seat Constituency System. We don’t want war ever again”(report from the study session on the single seat constituency system). Courtesy Sonoda Mineko |

SM It was! About three or four of us got together at somebody’s house at night to prepare the copy. It was all handwritten and mimeographed. We were all women, and it worked out well. Of course, so much of it was new to me. Even though Kōkyōso, the high school teachers’ union, acted like a company union at the outset, it was able to shed that character. Unlike Hokkyōso, which was strictly tied to the Socialist Party, Kōkyōso granted freedom of political affiliation. Communist Party supporters were the mainstream, though.

NF How about the coalmine union?

SM It was strictly Socialist Party, no freedom of party affiliation. As I got to know the families of the students, I realized how unsupportive the union was. If a father died on the job, the family would have to leave company housing, which was free. I remember one mother begging to be hired as a cleaning woman, or any sort of job. If she went to the union office to ask for help, she’d be told they were busy and be sent away. But she could hear them playing mahjong in the back room.

Or take something like flooding caused by trees being cut down to facilitate mining operations. I had joined the Mothers’ Liaison Committee (Hahaoya Renraku-kai), and we’d go to the company to point out the problems with this policy. It was a union official who’d meet with us, defending company policy!

As the mines were closed, one after another, the union would put up banners opposing closings. What they said publicly looked good, but they were negotiating behind people’s backs. No different from Komeito26 today! They said that if we kept on opposing the closings, the company would go bankrupt, and no one would get pensions. Our teachers’ union said this made no sense. On our home visits, we’d ask the parents to keep up the opposition.

Divide and conquer—that’s how all opposition gets crushed. The moms who stood firm till the end said they’d be shunned by the other moms when they went to the public bath. I remember the leader weeping.

Back in Yoichi, when I was apprentice assistant in the library, I never voted for the Liberal Democratic Party, but I did vote Socialist. But what I saw in Utashinai changed me. There was one father who died who’d been a subcontractor, so he didn’t even belong to the union. The company brought twenty or fifty thousand yen as a gesture of condolence. The mother said maybe her daughter, who was a student of mine, would have to quit school. In the next town, where about eleven people had died, the Communist councilman organized a bereaved families’ association. One of those families was told, “If you just split off from that group, we’ll hire your son at a good rate.” But this family told the others in the group, and everybody was furious. The family in our town asked me to represent them. Eventually, they ended up receiving compensation on a par with what they would have gotten if the dad had been a member of the Coal Miners’ Union. My student ended up not having to leave school.

That’s when I began to understand that it was the Communist Party that defended the rights of workers. How much I would go on learning from then on!

NF You leave Utashinai High School after 18 years. Isn’t that a long time to go without a transfer?

SM It must have been about the 12th year when I started requesting a transfer. But no school would respond. I talked to the principal. What did he say to me? “Do you think there’s a principal somewhere who’d want to hire you?” I had to say, “I suppose not.” “Just quit the union, and I’ll recommend you to any school.”

This principal had succeeded in achieving his goal of breaking up the union. Many teachers quit, but I didn’t want to. Unless I was convinced something was right, I wasn’t going to budge. You could say that I wasn’t very worldly. So, even though I’d built up credibility as a home ec teacher, my opposition to administration policies blocked my prospects for transfer.

NF Why did you want to leave a community that had been so important to you?

SM The home ec track had been eliminated from the curriculum, but there were other high schools that still had it. And Utashinai was really declining, with steady population loss from the mine closures.

NF How did you end up getting the transfer to Kutchan High School?

SM All those years after I’d been a student and then apprentice assistant at Yoichi High School, my mentors had advanced to important positions. One of them had become principal of a top high school in Sapporo. At a meeting for high school principals, he asked the principal of Utashinai why I’d been kept there all those years. That got him worried, and he said he’d do something about it. Pathetic, isn’t it?

Transfer after 18 Years! Kutchan High School

NF What was it like, moving to Kutchan High School? It’s not that far from Yoichi, where you grew up.

SM Kutchan’s completely different from the mining town of Utashinai. There, all the students were the children of laborers. In Kutchan, there was a Self-Defense Force post. Government offices. Shops. Farms. The overall atmosphere was conservative.

I came in and tried to do the same kind of teaching I’d done in Utashinai. Divide the class into groups of students who’d support each other, for instance. It made no sense to these students. They were baffled. In Utashinai, the students would set their own homeroom goals.

NF What about graduation? Pressure to feature the flag and anthem at school ceremonies has been a contentious issue.

SM The flag and anthem were used in Kutchan. In Utashinai, we teachers spent many hours to create our own graduation ceremony, not a ready-made one. So there was no Rising Sun flag on the stage. I can’t remember whether we sang the anthem or not, but I think probably not. We even cooked rice to serve everybody.

It took a year or two, but I eventually figured out how to connect with the students in Kutchan.

Part II (March 1988)

Kutchan Home Ec Student Responses to Sonoda Sensei

And so she did. When I interviewed Sonoda in 2014, we didn’t have time to discuss her experiences at Kutchan High School (1981-88) or Otaru Commercial School, from which she retired in 1993. She did leave me with a sheaf of classroom newsletters that followed one of her homerooms from the first through third and final year of high school; recorded the books in her homeroom libraries; and printed the responses to a video screening as well as that year’s course in home economics.

What follows are selections of excerpts from responses to the video and to the yearlong course, written in March of 1988. The video was Usagi no kyūjitsu, an NHK drama special from 1988. The title might be translated as “Rabbits’ Holiday,” reflecting the days when it was common to self-mockingly refer to Japanese housing as “rabbit hutches.”27 All the students registered shock at the extravagant sums required to realize the dream of “my home,” especially in the Tokyo metropolitan area, and reflected on the physical and psychological consequences of the two-to-four hour commute on the father and therefore on the other members of the family of four featured in the drama.

Responses to “Rabbits’ Holiday”:

- When I saw the condo of the man who appeared in the middle of the video, I could hardly believe it. The bed looked like a drawer. The room was the size of the short, narrow hallway leading from the front door of my house. The minute I saw it, I remembered that one of our handouts said, “If someone is living on it, even a single tatami mat constitutes a residence.” […] This condition hasn’t come about because of land shortage, but because corporations have bought up all the land. But given the state of our politicians, no matter how unsatisfied we might be, I think things will only get worse. […] Living in such conditions, “humans will stop being humans” […] they will be broken. This is the sad reality.

- I know that land is expensive, but I think most of the cost is attributable not to construction but to the profit that companies want to realize in sales. If the price of condos were to go down, I think there wouldn’t be people getting sick from overwork, suffering nervous breakdowns from mortgage payments or keeping up with the neighbors. […] When the couple in the video go condo hunting and ask abut the price and give their joint income, it really got on my nerves to see how the seller looked them over, with condescension. I don’t live in a condo or rental unit, so we don’t have to deal with the rent going up or paying off the mortgage […] When I saw the husband in the video raising his hand against his wife or having an extramarital affair, I thought I wouldn’t want a house of my own if it was going to cause so much damage.

- No doubt thanks in part to the strength of the actors, I felt that Japanese were to be pitied in some respects. Foreigners apparently think that Japanese are rich, but I think there are many aspects that are sad. Towards the end, there was a scene in which everybody was laughing so hard it was almost sickening, but I couldn’t help thinking that about the only thing you can do is laugh it off.

- In the beginning, land didn’t belong to anyone. I wish corporations would stop thinking just about their own profit and think about everybody.

- The Japanese people know something is wrong with these prices, but in the end, they let themselves get taken in by the industry. Realizing this makes me feel a little frustrated.

- We had our house built the year before last. There was a big pachinko parlor going up where we used to live, so we were asked to move out. Being a family of six, a condo seemed too small, so we decided to build a freestanding house. But every place we looked, land was expensive, and there would be the loan for the construction to pay back. The whole family worried together (just like in “Rabbits’ Holiday”). […] Monthly payments on the loan we got for the house amounts to something over 100,000 yen. It will be paid off when our dad turns 70, so about twenty more years. It’s enough to make you dizzy, right? […] Some times, we end up squabbling over this, but we always back off right away and get on with it. That’s what our family is like.

Impressions of the Class:

- I learned that high-school home economics goes beyond the mold of middle-school home ec, which was about sewing and cooking. […] We learned about the home, about our minds and bodies, pollution, the environment, the problems facing Japan. I feel sure the things I learned in this class will be practically useful in future.

- I’m really attracted to the single life, so I’m grateful for all the things I learned in this class. […] When I went home and told my parents, “You shouldn’t buy anything that’s more than five times your annual income,” my dad said, “They teach you things like that in home ec, huh? That’s a good thing.” That made me happy.

- What made me happiest of all was that you checked every single word in our notebooks. I like taking notes and sorting them out, but in language class, for instance, they never got checked, so you feel like a fool for putting effort into your notes. […] What was hard? The tests. Not only were there mid-terms and finals. Even if they didn’t cover a broad area, the questions were taken from the text, notes, and handouts.

- I’m really glad to have learned how to make broth. Cookbooks often have recipes that say, for instance, “2 cups of broth,” but they don’t tell you how to make the broth, so I’ve avoided those recipes. […] I took the handouts home and tried to make “clear broth with ‘squeezed’ egg (shimetamago).” I wanted to teach my mother how to make broth, or rather, I wanted her to watch me do it, but she said she already knew how. […] The broth tasted all right, but the egg ended up without enough flavor. I might have made a mistake with the amount of water. It was disappointing. But there was something else that was disappointing. What it comes down to is that my family seems incapable of savoring food. They slurped up this elegant broth as if it were no different from every day miso soup. It wasn’t worth making. Moreover, one page of the handout got all soggy, and I lost the other page. It ended up being an awful experience.

- I learned many things in the course of the year. Especially in knitting, I was able to learn new stitches, and when I finished knitting my gloves, I was really glad to have learned these skills. I was also glad that when we studied textiles, we examined the fibers under a microscope and sketched them. We also experimented with combustion, so I’m very glad that we were able to gain a detailed knowledge of fibers.

- I learned a lot about housing and how to make soap. I used to wonder if home economics was even necessary, but before, I didn’t know anything about heating or furniture. Without studying, I’d never have known about these things.

- Whenever anyone asked me in middle school what my least favorite class was, I answered without hesitation, “home economics.” […] Now that I’ve taken this class, it’s so interesting that it’s almost strange to me that I hated it so much before. I think it’s because every topic we took up was something that would actually be useful, that I paid serious attention. I especially remember the class on detergents. When we learned that the detergents we use are harmful for our bodies, I went home and told my mother about it right away. Once I turn twenty, I’ll be doing everything on my own, so I plan to be careful about choosing products that are good for my body.

- I can’t deny that I used to think home ec was an unnecessary subject. But after this year, I’ve begun to think it’s the most important one. […] I’ve always wanted to become a teacher. But I didn’t know what my subject would be. After this year, I’ve decided I want to become a home ec teacher. […] You have always said, “I hope the day will come when young men will study home economics alongside young women.” I would like that, too. If I work hard and succeed in becoming a teacher, I hope that will have happened. […] It’s possible that this year of study has changed my life.

Part III (December 23, 2015)

Postscript

NF Do some of the students keep in touch with you?

SM Oh, yes. Some have class reunions. They surprise me. I remember one time when the conversation turned to food preservatives, how important it was to pay attention. I asked, “What got you interested that?” “You’re the one who brought it up in class!” Funny, I never thought that student paid any attention in class.

NF You had some troublemakers?

SM Of course. But every time I encountered one, I thought about what I was like as a student and said to myself, none of them is as bad as I was.

NF Reading your students’ comments, I wondered what kind of adults they became—whether, for instance, they vote. Do you know anything about that?

SM Well, the ones who’ve kept in touch, if I think they’re sympathetic, I’ll call them at election time. Once, completely to my surprise, one of them answered my call and proceeded to try to persuade me to vote for Komeito. She was so rational. I was impressed!

NF I believe you’ve maintained a keen interest in political issues.

SM I take part in activities as I can—if there are rallies on Article 9 or the Ampo-related legislation, for instance. What’s going on in the schools now! Kōkyōso, the high school teachers union, distributed to its membership clear plastic folders with a “stop Abe” slogan (“Abe seiji o yurusanai!) printed on them. One of them was found on a teacher’s desk. An LDP-affiliated member of the Hokkaido Assembly brought this up, and now the Board of Education has sent out questionnaires to every school to find out which teachers have this folder.28 Teachers are being encouraged to report on each other! Can you believe it?

Or what I read in Dōshin (Hokkaido Shimbun) the other day, about how the Biei Township Social Welfare Council distributed flyers in the morning edition of the various newspapers that urged citizens to think about the Ampo bills being debated in the Diet. The Biei Branch of the LDP complained and four board members ended up resigning. The LDP folks complained that such political statements were inappropriate for a group that was supposed to be promoting social welfare.29

NF Why did they resign?

SM My point exactly!

NF What else are you interested in?

|

Sonoda Mineko in Otaru (June 27, 2014) Photo by N. Field |

SM Oh, I love art and music. Travel. Seasonal activities. Yesterday was the winter solstice, so I made oshiruko (sweet azuki-bean soup) with squash in it, which is what we do in Hokkaido. I’ll put some little things up for Christmas. And then there’s New Year’s coming up, of course. Oh, I’ve been studying historical documents for about ten years. A course organized by the city. It’s so interesting. I’m pretty much able to read the writing, so I’m just enjoying learning about the content. Especially about commoners in the Edo Period.

NF What a fine career you found!

SM I feel so fortunate. To have worked with so many young people. To still be in touch with them.

Norma Field thanks Mark Selden and Michele Mason for their attentive, caring reading of this manuscript and wishes she could have responded to all their suggestions. Heartfelt thanks go to Sonoda Mineko for sharing her life with patience and acuity, with frequent reminders of the sustaining, expansive power of collective commitment for both teachers and students, exemplifying a genuine practice of “no child left behind.”

Notes

See the fine new translation by Zeljko Cipris, The Crab Cannery Ship and Other Novels of Struggle (University of Hawai’i Press, 2013). See also Heather Bowen-Struyk, “Why a Boom in Japanese Proletarian Literature? The Kobayashi Takiji Memorial and The Factory Ship” (APJ Japan Focus, June 29, 2009) and Norma Field, “Commercial Appetite and Human Need: The Accidental and Fated Revival of Kobayashi Takiji’s Cannery Ship” (APJ Japan Focus, February 17, 2009).

As she states in the Afterword to her most recent poetry collection, Henshin (Ryokugeisha: Kushiro, Hokkaido, 2016), p. 141.

I was then ignorant of the history of home economics at the University of Chicago, my long-term employer. Marion Talbot headed a Department of Household Administration in 1904, in which students would address “‘the problems of the home and the household’ through such existing disciplines as physics, chemistry, physiology, bacteriology, political economy, and sociology.” Uncertainty over whether “study of the household deserved the University’s distinguished name” and declining enrollment led to disbandment in 1956.

Some of this aspirational language survives in an Education Ministry website, Waga kuni no kyōiku keiken (Kateika kyōiku). A critical history can be found in Tsuruta Atsuko, Kateika ga nerawareteiru: Kentei fugōkaku no ura ni [Home economics education under threat: Behind the failure to pass textbook screening] (Asahi Shimbunsha, 2004), especially Chapter 4, “Home Economics as Bearer of National Policy.”

See “Kateika wa dōtoku de wa nai!” [Home economics is not morals] in Tsuruta, pp. 86-93 and “Shōshi kōreika jidai no fukushi” [Welfare in an era of declining birthrate and aging population], pp. 96-104.

In English, see Alice Gordenker, “Sewing and Cookery Aren’t Just for the Girls” in the Japan Times (November 16, 2001).

CEDAW was adopted by the UN General Assembly in 1974, with Japan voting in favor. Careful examination revealed that 150 items in Japanese law contravened provisions of the Convention, leading to protracted contestation over whether Japan would actually ratify it. In addition to home economics, the Nationality Law and labor laws had to be changed before Japan could move to ratification in 1985, the final year of the UN Decade for Women. See Nuita Yōko, Yamaguchi Mitsuko, and Kubo Kimiko, “The U.N. Convention on Eliminating Discrimination Against Women and the Status of Japan” in Women and Politics Worldwide, ed. by Barbara J. Nelson and Najma Chowdhury (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1994), pp. 398-414 for a succinct, comprehensive discussion.

See David McNeill and Adam Lebowitz, “Hammering Down the Educational Nail: Abe Revises the Fundamental Law of Education,” APJ Japan Focus (July 9, 2008).

See Lawrence Repeta, “Japan’s Proposed National Security Legislation: Will This Be the End of Article 9?” (APJ Japan Focus, June 21, 2015). Passage of the legislation (dubbed “steamrolling” by its opponents) on September 19 has led to protests at the Diet on the 19th of each month.

See Brian Wakefield and Craig Martin, “Reexamining ‘Myths’ about Japan’s Collective Self-Defense Change—What critics (and the Japanese public) do understand about Japan’s constitutional re-interpretation,” APJ Japan Focus (September 8, 2014).

Satoko Kogure’s “Turning Back the Clock on Gender Equality: Proposed Constitutional Revision Jeopardizes Japanese Women’s Rights,” APJ Japan Focus dates back to May 22, 2005, but remains depressingly current. See also David McNeill, “Nippon Kaigi and the Radical Conservative Project to Take Back Japan,” APJ Japan Focus (December 14, 2015).

Massan was the NHK morning serial drama airing from September 20014 through March 2015. It recounted the travails of Masataka Taketsuru and his Scottish wife Jessie Roberta “Rita” Cowan as they pursued his dream of brewing genuine scotch in Japan. Sonoda’s reminiscences appear in Yoichi Bungei, No. 34 (March 31, 2009) under the title “‘Nikka’ ga tanoshimi o kureta: Kodomo no koro no omoide” (Nikka brought us pleasure: Memories from childhood).

As in sukūringu, the practice of bringing together correspondence students for actual classroom instruction.

Japan Women’s University established a correspondence division in 1948, according to its website.

Poet, novelist, critic, and translator (1905-1969). Rival of proletarian writer Kobayashi Takiji (1903-33) at the Otaru Higher School of Commerce. Later became known for his translation of Lady Chatterley’s Lover, which became the subject of a protracted trial, resulting in a guilty verdict from the Supreme Court in 1957.

Expression for “top student,” from the prewar practice of the emperor bestowing silver watches to top graduates at select institutions (in the case of Tokyo Imperial University, until 1918).

The roots of this Methodist mission school go back to 1874, when missionaries from the Methodist Episcopal Church of the U.S. established a girls’ elementary school.

At its peak in 1948, Utashinai counted approximately 46,000 residents It has been Japan’s smallest city for some time now, with a population numbering 3,615 as of April 30 2016, according to the municipal homepage.

As is often the case, standardized testing in schools has been a controversial subject in postwar Japan. More familiar than the high school testing under discussion here is the Scholastic Achievement Test (gakuryoku tesuto) in compulsory schooling, that is, elementary and middle schools. The struggle over its implementation led to court battles through the 1960s, culminating in a Supreme Court decision in 1976. For a discussion in English, see Teruhisa Horio, Educational Thought and Ideology in Modern Japan: State Authority and Intellectual Freedom (University of Tokyo Press, 1988), pp. 180-87, 213-45. The original, unrevised Fundamental Law of Education (see McNeill and Leibowitz) was crucial in these struggles. The title to chapter 8 in Horio’s text captures the essence of what was at stake, for compulsory education as well as the high school testing that Sonoda Mineko encountered in its early stages: “The Ministry of Education’s Scholastic achievement Test: Economic Growth and the Destruction of Education” (p. 213) The Scholastic Achievement Test fell into abeyance for nearly 40 years but has been revived in the 21st century.

Common shortened form for Nichibei Anzen Hoshō Jōyaku, or the US-Japan Security Treaty, as it is commonly referred to in English. Deriving from the San Francisco Peace Treaty of 1951, it has notably provided for stationing sizable numbers of US troops in Japan, most significantly in Okinawa. The 1960 revision and renewal occasioned the largest mass protests in postwar Japanese history; the 1970 renewal stirred mass student uprisings. The Treaty is once again in the public eye with the second Abe regime’s heightened campaign for Consitutional revision through such measures as passage of the law legitimating collective self-defense law and insistence on relocating the Marine Air Corps Station in Futenma to Henoko Bay in Okinawa despite sustained, concerted opposition.

Acronomym for Kateika Kyōiku Kenkyūsha Renmei, or League of Researchers in Home Economics Education. According to the website, it is a nongovernmental research organization established in 1966, “in order to confront the reality of the lives of the people of Japan, to overcome the contradictions therein, and to strive to clarify directions for practice.” The summer 2015 assembly issued an appeal to mark the 50th anniversary of the organization’s founding by affirming the Constitution and the UN Convention of the Rights of the Child as a means for placing children at the center of efforts to safeguard life, peace, and democracy. Recent documents on the website reflect concerns about respecting children as autonomous beings, not the possession of parents and adults; practices necessary for achieving gender equality; domestic violence; sex education as a component of home economics; and LGBT youth.

See Horio, pp. 269-78 for how teachers sought to sustain their research and in-service training independently of, and indeed, in the face of discouragement by, the Education Ministry.

The political party formed in 1964 as the political wing of the postwar Buddhist organization, Soka Gakkai (“Value Creation Study Association”), junior coalition partner of the Liberal Democratic Party since 1999. The tension between the pacifism proclaimed by the religious association and the implication of partnership with the LDP, which has long been determined to undo Article 9, the “no-war” clause of the Constitution, came to a head last September with the forcible passage of the security legislation in September 2016. See Levi McLaughlin, “Komeito’s Soka Gakkai Protestors and Supporters: Religious Motivations for Political Activism in Contemporary Japan” (APJ Japan Focus, October 12, 2015).

According to the entry for “usagi goya” in the etymological dictionary, Gogen yurai jiten, the expression originated in a 1979 informal EC (European Community) report on strategic responses to Japanese economic strength. “We live in rabbit hutches” went on to become a derisive and, I can’t help thinking, wistful expression of Japanese recognition of the gap between economic prowess and the actual experience of everyday life on the part of most individuals.

“Abe seiken hihan no mongoniri bungu, umu o chōsa; Hokkaido no gakkō” in Asahi Shimbun ( October 15, 2015).

Regional social welfare councils (shakai fukushi kyōgikai) are non-governmental organizations. See “Biei-chō shakyō no Ampo chirashi ni Jimin yokoyari; Shobun yōkyū; ‘konran maneita’ 4 riji tainin” in Hokkaido Shimbun (December 13, 2015).