Abstract

During the late 1930s, as Japan escalated war preparations with China, and after Governor-General Minami formalized the assimilationist ideology of “Japan and Korea as One Body”, cinema in Korea experienced a fundamental transformation. Korean filmmakers had little choice but to make co-productions that aimed to draw Koreans toward Japanese ways of thinking and living, while promoting a sense of loyalty to the Japanese Empire. Within this colonial context, and especially after the 1940 Korean Film Law facilitated the absorption of the Korean film industry into the Japanese film industry, a particular type of masculine hegemony was encouraged by a comprehensive censorship process. To show how this fluid and dynamic process worked, this article draws on some key theoretical concepts of hegemony to analyze the construction of masculinity in three of the most notable of these wartime co-productions: Angels on the Streets (1941), Spring in the Korean Peninsula (1941), and Suicide Squad at the Watchtower (1943). It analyzes how the colonial authorities sought to reorient Korean audiences toward a particular worldview by means of a process that we call a “cinema of assimilation” – a cultural hegemonic exercise designed to draw Koreans closer to the social, political and economic habits and priorities of their occupiers.

Introduction

Cinema in colonial Korea (1910-1945) experienced a key turning point following the March First Independence Movement in 1919, which had inspired a number of nationalist protests against the Japanese occupation. Although the movement was violently quashed by the military-led Korean Colonial Government (hereafter KCG), Governor-General Saitō Makoto thereafter sought to relax Japanese administrative control over Korean cultural and artistic activities. Writers, actors, filmmakers, theater entrepreneurs, and other intellectuals grasped this opportunity to express Korean culture, giving rise to a level of cultural nationalism and colonial modernity beyond a simplistic “imperialist repression versus national resistance” construct (Robinson 1988; Shin and Robinson 1999). Enabling Koreans to gain film production training and experience – or at least not preventing them from doing so – stimulated the birth of a Korean “occupied” cinema (Yecies and Shim 2011).

However, in 1937 as Japan began escalating preparations for war with China, and after Governor-General Minami Jirō formalized the assimilationist policy of naisen ittai (naeseon ilche in Korean), meaning “Japan and Korea as One Body” in 1938, colonial Korea underwent some fundamental changes.2 During this period, the KCG used locally produced feature films as tools to draw Koreans toward Japanese ways of thinking and living, thus encapsulating Japan’s attempted manifestation of cultural hegemony over Korea.

In particular, the Japanese authorities enforced a strict film policy that prohibited the exhibition of Western entertainment and “spectacle” films while promoting pro-Japanese propaganda films – made under a “system of cooperation” (Chung 2012).In this environment, Korean filmmakers collaborated with their Japanese counterparts and “co-produced” films that promulgated a sense of unity between the two nations, and attempted to reaffirm loyalty to the Japanese Empire in the minds of its colonial subjects.

Under the 1940 Korean Film Law, all films made in Korea were subject to strict censorship. Scripts could be banned, and thus never reach production, if they “misrepresented” Japanese national culture or detracted from the advance of Japan’s “ideological project” in Korea. The narrative themes and images expressed in the surviving films co-produced by Korean and Japanese filmmakers following the enactment of the Korean Film Law offers insights into how the Japanese occupation authorities endeavored to capture the hearts and minds of their colonial subjects. In so doing, a particular type of masculine hegemony was constructed – a phenomenon that, although fluid and dynamic in character, grew directly out of the exhaustive approval process of colonial censorship.

In order to show how this process worked, this article draws on some key concepts in the theory of hegemony to analyze the construction of masculinity in three of the most notable films co-produced by Korean and Japanese filmmakers in the early 1940s: Angels on the Streets (hereafter Angels), Spring in the Korean Peninsula (hereafter Spring), and Suicide Squad at the Watchtower (hereafter Suicide). While these three “transcolonial coproductions” (Kwon 2012) have drawn a variety of critical responses, the present study sets out to explicate the conditions and consequences of socio-political change through film, rather than explaining the effects that the production and dissemination of these films produced on audiences. In adopting this approach, this article shows how the occupation authorities sought to reorient Korean audiences toward a particular worldview in a process that we call a “cinema of assimilation” – a cultural hegemonic exercise designed to draw Koreans closer to Japanese social, economic and political (in other words, cultural) ethics and practices.3 In other words, Japan sought to exploit cultural mechanisms such as film and other fictional constructions of masculinity in order to create a new hegemony – especially after 1940 when Korean filmmakers had been entirely absorbed by the Japanese film industry.

In terms of hegemonic theory, these productions were intended to infiltrate the national-popular consciousness, bolstering the Korean people’s innate “commonsense” with the “good sense” of the Japanese. As far as film was concerned, the crucial nexus in this process of transition to good sense was the assignment of gender roles. The hegemonic moment emerges in a way that sees not just the marginalization of women through roles as whore or mother, but in a manner that ensures that films (and the films discussed in this article in particular) become a key social and cultural mechanism that underscores the interests of men (Kyung Hyun Kim 2004: 8). In these ways, the three films under discussion replaced the escapist experience that had previously been a strong element of cinema-going with an intensified type of propaganda cinema of assimilation.

The concept of cultural hegemony has received substantial attention in the various branches of film and media studies.4 A number of articles are noteworthy for indicating the innovative ways in which the concept of hegemony is being applied, as well as the breadth of analysis of the concept. For those interested in cinema and politics, Hollywood’s appeal is seen as transnational while also reflecting a hegemonic struggle around the construction of democratic subject positions and the expansion of a particular national identity (Semati and Sotirin, 1999). For others focusing on genre, the James Bond action movie franchise effectively diffuses American values on a global scale, thus contributing to the duplication of American hegemony (Shin and Gon 2008). Beyond the aforementioned studies, there is no doubt that the concept of hegemony continues to make a substantive contribution to research on film (and the media more broadly) as a cultural mechanism that is key to the dissemination of particular views and understandings of society. What becomes immediately apparent from a review of the literature, however, is the failure to adequately describe and define how this phenomenon actually operates; this, in turn, leads to easy assumptions and a taken-for-granted attitude to the process of gender construction. Such attitudes are evident in Corkin (2000), Gerteis (2007), and Min (2003). Although “hegemony” either figures explicitly in the title alone, or appears throughout these former studies, the concept is never explained or defined. This taken-for-granted attitude wrongly assumes that the reader understands the significance of hegemony at both the cultural and national-popular levels. While trying to avoid a detailed critique of the application of hegemony to film and media studies, we will attempt to fill this existing theoretical lacuna and offer a definition and description of the concept as it applies to film in the Japanese-Korean context.

Cultural Transformations: A Theoretical Framework

To build on some of the important work discussed above, the present work explicates the socio-political conditions and consequences of the use of film in relation to the hegemonic processes to which colonial Korea was subjected. To do this, the work on hegemony by Antonio Gramsci is examined, in particular his notes on the relationship between “commonsense” and “good sense” and, most importantly, the transformation of the former into the latter. The failure of previous scholars to adequately link the concept of hegemony with film in Korea (let alone film in general) is the primary motivation in presenting this discussion.

For Gramsci, the concept of hegemony defines an ethico-political moment when the ideas and practices of a particular group within a society assume ethical and political authority. To retain power, this group must unite the ethical or societial component with the coercive or political component to build a new “Integral State” that is, a new amalgam of political society + civil society (1971: 263). It is this expansion of the state beyond the political, economic and social spheres (as conventionally understood) so as to incorporate the average citizen (and their private values) that Harvey (2005: 39) identifies as crucial to the acceptance of a new “hegemonic moment”. This explains why it was necessary for Japanese colonialism in Korea – which may not have relied on hegemonic tactics at the outset of the occupation – to eventually extend its control into the private sphere of communities, families and individuals.

This process was not simple or straightforward: it involved making the “commonsense” of the Korean people subaltern while simultaneously infusing it with the nascent “good sense” of the Japanese. This kind of transformation is important to understanding the success or failure of hegemony to develop (Howson and Smith 2008: 4). As a quotidian ideology, commonsense demands conformism and reflects the everyday life and beliefs of a particular social group that, in turn, expresses its cherished cultural traditions. Inherent in the concept of commonsense is a particular ethical and political legitimacy that provides the basis for the identification of a given group, and that in turn influences its relationship to authority. However, for the Japanese, the insertion of their interests into their military-led colony required an immediate engagement with the broader Korean culture in order to legitimate and progress these interests and to present them in terms of “good sense” rather than raw domination. This is the basis for Caprio’s characterization of the Japanese as a hegemonic people during the colonial period (2009: 50).

A consequence of this hegemonic transformation is that for the colonizing group whose interests are seen to become ascendant, there is a belief that the society affected will in turn move from disunity to unity. This desire for unity fitted well with Japan’s belief that it held a great deal in common with the Korean people, to the point that Japan saw its actions as a form of integration rather than colonization – or what Cumings (1997: 141) calls “substitutions”. However, any such imposition of authority and subsequent unity is always provisional, and it is this that produces hegemony’s dynamic character or, as Gramsci (1971: 182) called it, its “unstable equilibria”. Furthermore, such dynamism and conflict always operate at the level of the “national-popular” consciousness in society. However, by unpacking the nature of Japanese colonial hegemony – in this case through the use of film as a key hegemonic mechanism in the creation of a national-popular consciousness within a broader popular culture – it is possible to expose the socio-political conditions for the emergence of a new hegemony; or, conversely, to demonstrate Japan’s failure to create an ethico-political moment in Korea and thereby secure its desired hegemony.

Connell’s (1995: 76) framework for conceptualizing hegemonic masculinity has proved particularly fruitful in the present exploration of Korean gender constructions. She focuses on two key ideas: first, that the masculinity it re-presents is the only legitimate way for men to think, aspire and act towards creating an ideal masculinity; and second, that by building complicity with the hegemonic ideal, men will secure the dominance of their own gender while continuing the subordination of women. Connell here illustrates how a particular construct of masculinity becomes a component of a broad culturally based hegemony, assuming a parallel authority to more political and economic ideals such as democracy or capitalism. Connell thus exposes the two key constitutive parts of authority: legitimacy and power. Power operates through the ability to subordinate a particular group (or idea/practice) through the operation of particular configurations of identification and practice that enable men to position themselves in relation to it [hegemonic masculinity] (Connell and Messerschmidt 2005: 832). Thus, it was never crucial for Korean men to practice and assume an identity based on an ideal Japanese masculinity. Rather, for the vast majority of Korean men (and women as well), either as individuals or groups, it was enough to adopt certain practices that would enable them to align or position themselves in relation to what they increasingly perceived as the legitimate form of masculinity – a strategy that would in turn enable them to gain the social, political and economic advantages they sought.

While this process of alignment acts to modify the behavior of men (and women), it is also a key contributor to the constitution of power with a given society and, as a consequence, defines what is legitimate with respect to issues of identification and identity. It is this ability to confer identity and the associated advantages that men (and also women) seek to acquire that enables hegemonic masculinity to assume the authority of an ideal within a particular cultural situation or system. Describing gender-based behavior in empirical terms will only ever tell part of the story. The modernist narrative of rational men practicing a form of masculinity that will benefit them and the social system of which they are a part must be re-thought in terms of the re-presentation of a culturally authoritative or hegemonic masculinity. In Korea, film became a key mechanism in perpetuating a gendered hegemony.

Developing a New Cinematic Order

In 1937, as Japan was preparing for war with China, film exhibition in colonial Korea began experiencing fundamental changes. The shifting struggle for dominance of Japanese films on local screens, as well as the coming of sound, was instrumental to these changes (Yecies 2004; Yecies 2008).5 In this context, Korean filmmakers began seeking out increased co-production opportunities with Japanese colleagues – some of whom had been working in Korea from the early days of filmmaking, and Japan’s major studios including Shōchiku, Tōhō, and Shinkō Kinema. Soon, they would have little choice in the matter. Within a year, Japan had escalated its war-preparation efforts by unleashing a program of “unbridled nationalistic consciousness” throughout its Empire.6 As part of this campaign, the KCG’s censorship apparatus began blocking the entry of films with “Western” themes by banning nearly all films imported from the U.S. When read in the context of a nascent cultural hegemony: “Authorities and audiences found that harmless entertainment was never harmless, especially in a colonial space” (Baskett 2008: 22). Effectively, the ban prevented Korea’s 120 cinemas from screening American films, and Korea now became a key exhibition market for Japanese products.

By August 1940, the production, distribution, and exhibition of all films in Korea had come under the control of the Korean Film Law, a replica of the 1939 Japan Film Law. This policy created the legal foundations that gave rise to an ethico-political framework for a new production system. It controlled every part of filmmaking, and every member of the industry was now required to follow a mandatory registration protocol in order to maintain his or her active status.

In order to adapt themselves to this new policy environment, Korean film workers had begun using the Japanese “national” language and adopting Japanese names and—at least on the surface—expressing the nationalistic ideals expected by the colonial administration. Hence, the Korean Film Law challenged filmmakers to rethink their role as producers of creative and cultural contents in order to ensure their survival – a response that included keeping their names and ID numbers active in the colonial authorities’ comprehensive database of certified talent in Korea.

As the ideology behind the procurement of entertainment films changed, so too did official thinking about what was being produced for “educational” purposes at home and in Japan’s colonies. During this time, the domestic film industry displayed a sense of eagerness to do its part for the war effort, particularly since there was a very good chance of audiences seeing its dramatic feature films if they were endorsed by the Japanese Department of Home Affairs.7 Under Governor-General Jirō’s banner of “education is the guiding force behind national culture”,8 Korea’s film industry was transformed into a new type of propaganda tool that followed the assimilationist policy of naisen ittai and the monolingual use of Japanese language by students inside (and outside) all schools (Dong 1973: 168; Rhee 1992: 94). The advent of this state-controlled production system forced Korean filmmakers to comply with the new rules regulating their industry which controlled every aspect of the filmmaking process. Of the 51 films in the Korean Movie Data Base (aka KMDB) known to have been made in Korea between 1937 and 1945, almost all were intended to imbue Koreans with the ideology of “Japan and Korea as a single body”.9 Under Governor-General Jirō’s heavy-handed rule (1936–1942), these productions were used to serve the larger aim of helping to “mould our national character, to form our national morals, to cultivate a firm and fiery national faith . . .” (Government-General of Tyosen 1938: 227). Not surprisingly, Koreans had little choice but to comply with Japan’s tightening grip on all aspects of cinema culture – including the requirement to speak Japanese in films.

While filmmakers from both parts of Japan shared misgivings about having to produce propaganda films, Japanese filmmakers (such as Tasaka Tomotaka, Saito Torajiro, Toyoda Shiro, and Imai Tadashi) genuinely looked forward to collaborating with their Korean counterparts, whose creativity was well known despite their limited technical opportunities (Ōta 1938: 12–13). The consensus among Japanese critics writing in popular film and entertainment magazines such as Kinema Junpō, Eiga Hyōron, Nihon Eiga, Eiga Junpō, and Shin Eiga was that Korea’s film market was a new, lucrative exhibition and production frontier with great potential for collaborative projects. Hence, increased opportunities for Koreans to work with Japanese filmmakers, in turn, had lead to benefits such as gaining access to cutting-edge equipment and other scarce film supplies.

Three representative films made amidst the atmosphere of patriotic fervor and rising war hysteria – Angels, Spring, and Suicide – illustrate the ways in which filmmakers in Korea were exploring and interpreting the concept of naisen ittai following the passing of the Korean Film Law in 1940. These films not only attempted a “code-switch” into Japanese along linguistic, cultural, and political lines (Kwon 2012), but in the process they employed particular constructions of masculinity as a vehicle for demonstrating unity and loyalty in a process of “becoming one body” with Japan.

From Attraction to Assimilation

In 1934, Governor-General Ugaki ruled that 25 percent of all pictures shown in Korea had to be of “domestic” origin—meaning Japanese or Korean.10 As the number of foreign (primarily Hollywood) films was reduced, so too the colorful promotional activities linked to the dynamic cinema-going culture of the 1920s to the mid-1930s, or what has been termed the “golden age of Hollywood in Korea” (Yecies 2005), underwent a steep decline.

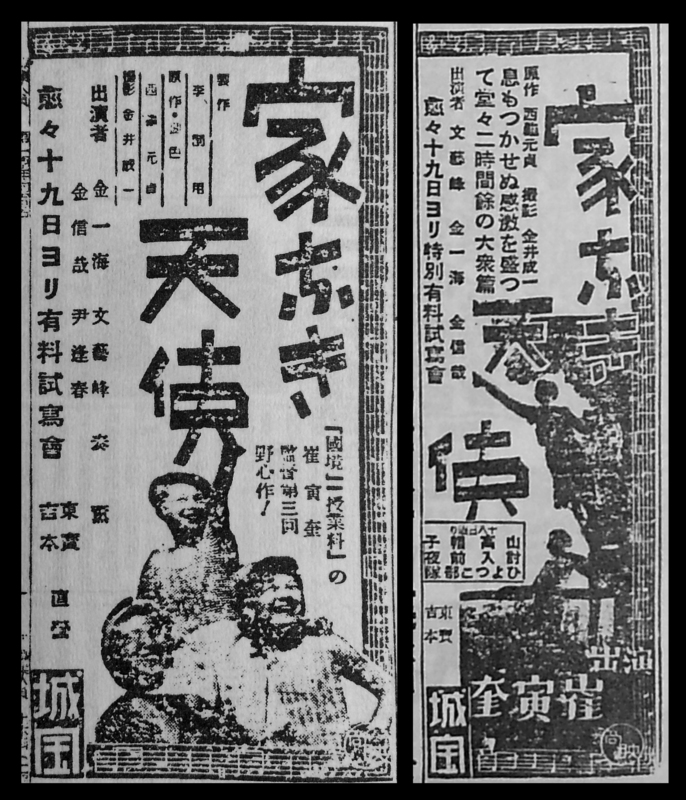

The gap left by the Hollywood spectacle films that had until the mid-1930s attracted and thrilled audiences across Korea was filled by a new breed of feature films designed to inculcate “educational” messages intended to transform the Korean people into loyal subjects of Japan. Angels was one such film. It was made with an all-Korean cast including domestic stars Kim Shin-jae, Lee Wuk-ha, Kim Il-hae, and Mun Ye-bong. No Japanese characters appeared in the film. This Korean-language drama, directed by Choi In-gyu (also known as Choi In-kyu, Che In-gyu, or Sinkei Jaku in Japanese), was inspired by the true story of a pastor who rescued homeless children (mostly young boys) in Seoul and resettled them in an orphanage in the countryside (The children’s exuberance resulting from their new lease on life is clearly displayed in the Korean newspaper advertisements in Figure 1.) At the time of its release, despite being mainly in Korean (with Japanese subtitles), Angels was one of the most popular Korean films to be exhibited in Japan, garnering praise as a “Ministry of Education recommended film.” This “thrilling masterpiece”, which ran over two hours, was approved by the censorship board in Korea in mid-July 1941, and was given a special screening in Japan in September 1941 (Sakuramoto 1983: 186; High 2003: 307–308).

|

Figure 1. Angels on the Streets. Advertisements. Maeil Sinbo (16 February 1941: 2; 18 February 1941: 2 – left to right). Author’s own collection. |

At odds with this positive reception was the view expressed by the Japanese Home Ministry that the film had been tarnished by scenes portraying Koreans in traditional dress and speaking in their native tongue. It appears that the Minister of Education had lent his support to a Korean-language film at a time when speaking Korean was frowned on by the colonial authorities. But there was another side to this decision. The strategy of using the Korean native tongue showed the integrative direction favored by the Japanese authorities – among other benefits, it ensured that Koreans would engage with the film, especially those whose proficiency in Japanese fell below the standard desired after Korean had been banned in schools.

The discovery in 2005 of a print of Angels has shed new light on the film and its possible reception.11 Watching this film more than half a century after its initial release is instructive because of the unmistakable hegemonic message it embodies, while also demonstrating how thoroughly assimilated Korean filmmakers had become with respect to the ideology of naisen ittai. The analysis herewith is designed to open up discussion about the particular visual and narrative representations of the new hegemonic masculinity employed by the filmmakers. Most importantly, by setting out the values and practices that men should aspire to it created direct links with the new colonial cultural hegemony. (Previous analyses such as the essay by Mizuno (2012) focuses on the strong female orphan who conspicuously – and perhaps unexpectedly – aspires to become a medical practitioner; this choice not only represents the marginalization of women, but shows that where they are visible it is only to follow the values and practices of men.) The two male protagonists exhibit a vital agency and moral superiority that is closely linked with submission to Japanese rule and loyalty to the Emperor.

|

Figure 2. Film stills from the KOFA DVD Angels on the Streets (1941). Author’s own collection. These images exemplify some of the ways that this film constructs representations of traditional gender relations within the complex discourses of colonialism and modernity. Men take leading roles in this film (and in the other two films under discussion). The stills reproduced here represent women in menial positions such as barmaid/hostess, office assistant, doctor’s assistant, and many are occupied with household tasks such as cleaning, cooking, and serving meals. Of note is the top-right image picturing a bar scene in which Dr. Ahn speaks with Myung-ja, the street orphan who yearns to become a physician. |

The film opens at a bar in Jongno District, which lies in the social and cultural heart of Seoul. Two men are bartending while hostesses wearing a variety of clothing styles, including traditional Korean hanboks and Japanese kimonos as well as Western-style dresses, serve and drink with the customers. Dr. Ahn, the wealthy Korean owner of a medical clinic in Jongno, in addition to a farm and a large riverfront house, is drinking heavily while seated alone at a table. He is approached by Myung-ja (played by colonial and post-colonial film star Kim Shin-jae) and her brother Yong-gil – two homeless “street angels” in tattered clothes and with flowers and cigarettes for sale. Unlike all the other occupants of the bar, Dr. Ahn extends a compassionate smile to the children and gives them money. His warmth appears in stark contrast to the abusive adults (likewise homeless and ragged squatters) who are “looking after” Myung-ja and Yong-gil in some dank room.

The narrative elements in these opening scenes – particularly where the representation of male characters is concerned – construct binary links between wealth, happiness, compassion, generosity, social mobility, and “good citizenship” on the one hand, and poverty, unhappiness, cruelty, social exclusion, and “poor citizenship” on the other. Throughout the film, Dr. Ahn maintains an attitude of benevolence toward his fellow Koreans – especially by sharing his holiday house and farm compound with his brother-in-law (a minister), who is selflessly building up a self-sustaining community of street children who are destined to become volunteer soldiers in the future.

Both the minister and the doctor function as surrogate fathers to the children (and the other characters in the film) – or at least as their guardian angels. Both men show traits of leadership in the community, and both men lead efforts to unify and transform the group (all Koreans) as though each member (young and old) is in need of “rescue” or “repair”. Through their actions and words, both advocate obedience, loyalty, and honor in terms of “good citizenship”, which in this context means being a good colonial subject. For example, Dr. Ahn treats people who are sick in body and spirit. At the end of the film he fights to defend the children against evil homeless men – who have come to the farm to seize Myung-ja and Yong-gil – but then treats their (literal) wounded bodies and (figurative) souls after the men are injured during a big chase scene across a collapsing bridge. The men agree to let the good doctor “operate” on their sinful souls, which he does by advising them to change their ways and to avoid dishonorable behavior in the future (he also gives them money). Following this symbolic undertaking, which swiftly resolves the conflicts between the characters and transforms them, Dr. Ahn turns away from the now changed men and pauses to face the Japanese flag being raised by the minister.

This coda to this final scene, which is set on the riverbank facing the farmhouse, shows the mixed group of orphaned children and adults bowing in unison and jointly pledging their loyalty to the Empire. The eldest boy in the group shows his budding leadership potential by asking everyone to bow, and then leading the citizen’s pledge of loyalty to the Emperor in Japanese—a language the orphans do not use elsewhere in the film. (In the bottom right still in Figure 2, notice how the women and the wounded evil homeless men are kept outside of the all-male circle of loyalty.) Although this scene is awkwardly inconsistent with the rest of the film, Korean producer Lee Chang-yong was no doubt aware that this ending, with its emphasis on unity between Japanese and Koreans, would meet with the approval of the colonial authorities and censorship offices in both Korea and Japan.

Given the severe limitations placed on the industry at this time, Angels is notable for its aesthetic achievements. Some prominent Koreanscholars, including Lee (2004: 202), have noted that the depiction of poverty-stricken, homeless children,played by amateur actors on real locations, predates the major worksof the Italian neorealist movement such as Open City (Roberto Rossellini, 1945) and Shoeshine (Vittorio De Sica, 1946). The strong sense of realism in Angels undoubtedly reflected the harsh social conditions underwhich Koreans were living at the time, although this may not have been intended asa critique of Japanese rule. After completing Angels, Choifine-tuned his loyalty to the Empire by producing stronger propaganda textsendorsing male-led militarism, elevating the concept of “collaboration” withKorea’s Japanese overlords to the status of a systematic program.12

In a different way to Angels, Lee Byeong-il’s first film, Spring, provides insights into events both within and outside the film industry in the early 1940s.13 It demonstrates once again how filmmakers embraced the ethic of naisen ittai and educational messages about mutual cooperation and loyalty to the Emperor. However, this message is presented in such a way so as to emphasize the ability of men in particular to ultimately overcome misadventure and misconduct to become role models for society. Female characters by contrast are seen only in passive and subaltern roles. It is impossible to ignore the gendered nature of this film and the message it projects. Spring is a melodrama portraying a complex love triangle set against the backdrop of colonial Korea’s film and recording industries, which were struggling as the result of underdeveloped production conditions. Its most intriguing feature is its re-creation of the making of The Story of Chunhyang (hereafter Chunhyang), a classic Korean tale (depicted in the top-left newspaper advertisement in Figure 3).14 This film-within-a-film, which had its origins in a traditional love story and folk tale – and was also the basis for the first ‘successful’ Korean talkie (made in 1935) – embodies the concept of loyalty, regarded as the quintessential Korean virtue. The juxtaposition of the loyalty shown by a woman to her husband with the loyalty of Korean males to Japanese values constitutes the key gendered dynamic of the movie.15

|

Figure 3. Spring in the Korean Peninsula (1941). Advertisements. Maeil Sinbo (5 November 1941: 1; 6 November 1941: 3; 8 November 1941: 1 – left to right, and top to bottom). Author’s own collection.The bottom advertisement includes a promotional tie-in campaign for Newtone, a blood replenishing and energizing cure-all-ailment tonic, which is also featured in a window display case in the inserted documentary footage of the cinema screening the Chunhyang film-within-the-film. |

In the 1941 film, the producer of Chunhyang attempts to cast his friend’s sister, eventually securing a role for her when the lead actress is fired. Predictably, the producer and sister fall in love. (The couple and their two friends, who also fall in love, appear in the top-right and bottom advertisements in Figure 3.) The male-dominated production (pictured in the top-left still in Figure 4) carries on until the manager of the recording company involved in the production, Mr. Han (who is Korean, but also speaks Japanese), tries to seduce the woman. When this scheme fails, he withdraws his investment funding and halts production of the film. In desperation, the producer steals money from the recording company, but is caught and sent to jail. However, the police, who speak Japanese – a patent symbol of colonial authority – show compassion and release him because he shows promise in the film industry. Meanwhile, a new film company (Bando Film) has been created, which foreshadows the consolidated Chosun Film Production Corporation formed as a result of the 1940 Korean Film Law.16

|

Figure 4. Film stills from the KOFA DVD Spring in the Korean Peninsula (1941). Author’s own collection.Whilst the representations of women – particularly in the workforce – in this film are more varied than in Angels on the Streets, they remain passive one-dimensional constructs who are subjugated by colonialism and traditional gender relations. TL and TR: woman as passive observer and passive object of the camera and crew’s gaze on the studio set of the Chunhyang film-within-the-film; ML: serving men as bartender and hostess; MR: office assistant in the recording company; BL: performing domestic chores; BR: the Chunhyang director, film crew, and their friends farewelling the producer (and his fiancée) who are heading to Japan. |

The local film industry portrayed in Spring, which was a box office success, serves as a cipher for the wartime Korean film industry. At a dinner ceremony, the company president announces (in Japanese, thus addressing the cinema audience as well as the dinner guests) that Bando Film will make “cultural enlightenment” films presenting Japan and Korea as one nation, and that their first project will be the completion of Chunhyang – an ideal vehicle for merging Korean culture with Japanese technological expertise in the new policy environment. However, not everyone present is overjoyed about the company’s formation and its takeover of Chunhyang. The director has no money to rent a production office, and the company’s filmmaking methods lag far behind those utilized in Japan proper. His melancholy is in stark contrast to the happiness around him. (His gloomy face appears in the top-right and bottom advertisements in Figure 3.) After all the intersecting love interests have been untangled, the producer (accompanied by his friend’s sister) is sent to Japan on a special assignment. As representatives of the Korean film industry, they are charged with visiting all of Tokyo’s film studios to learn the latest methods of collaborative filmmaking, all in the name of naisen ittai – a clear reference to the founding of the Chosun Film Production Corporation. Collaborating with Japanese filmmakers – a foreshadowing of the wholesale consolidation of the production and distribution industry in Korea – is held up as a ray of hope for the local industry’s future.

Finally, the action film Suicide offers an expanded view of the imperial ideology of naisen ittai – one without any of the awkwardness and ambiguity about gender found in Angels and Spring.This film made no bones about the operation of gender and its importance for maintaining stability and achieving success for the Empire. As the present study will show, men are the central characters of this film, and this is particularly true of the point where the gender hierarchy and the ethnic hierarchy of the early 1940s intersect. Chinese and Korean men are regarded as inferior to their Japanese counterparts, while the female characters are also aligned according to a hierarchy – one that imitates the male model but fills an inferior position. Having said this, Yong-suk as the “lady doctor” plays significant role in the film insofar as she offers a challenge to this gender and ethnic hierarchy – in the end, caught within the ethnic colonialist structures that underpinned Japanese hegemony, her position is ultimately subordinated to the male characters. With its clear-cut boundaries, the film provided a model for imperial filmmakers by demonstrating how co-production ventures were feasible while also promoting a clear ideological message: Koreans are imperial citizens and selfless dedication to the Emperor and the Empire will lead to national salvation.17

Suicide wasa 90-minute Japanese–Korean co-production made by Tōhō, one of Japan’s leading film companies, and the Chosun Film Production Corporation. It emulated the American action films popular with local audiences while utilizing the conventions of Japanese wartime documentaries (Anderson and Richie 1982: 130). The KCG supported Suicide with financial and in-kind infrastructural support over its three-year production period. The film was directed by Imai Tadashi, who would later become a prolific and controversial film director, not least because he infused his postwar films with a strong left-wing ideology. The assistant director was Choi In-gyu, of Angels fame. The film starred popular Japanese actors Takada Minoru and Hara Setsuko, known for her many roles in Japanese war films, and the well-known Korean actors Kim Shin-jae (also from Angels) and Jeon Ok.

|

Figure 5. Suicide Squad at the Watchtower (1943). Advertisements. Maeil Sinbo (24 April 1943: 4; 28 April 1943: 3; 30 April 1943: 2; 4 May 1943: 4 – top to bottom, and left to right). Author’s own collection. |

Resembling American action stories of the period such as I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang (1932), Mutiny on the Bounty (1935), and Captain Blood (1935)—films which all screened in Korea in the 1930s—and drawing on Japanese wartime documentary aesthetics, the film is set around a border security watchtower in the north of Korea. The story portrays the selfless devotion of border policemen in Korea and Manchuria in 1935, before the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War. In the village beneath the snow-covered mountains that surround the watchtower, Japanese, Chinese, and Koreans live together in harmony. Attacks from Chinese “bandits” (resistance groups opposed to Japanese occupation and thus enemies of the state) threaten their peaceful life. In one scene, a Korean policeman and a Chinese restaurant owner are killed while confronting these bandits. When the battle begins, male and female villagers hide in the local police station and contemplate a Japanese-style group suicide (predominantly a male tradition), a practice rarely found in Korea, rather than face surrender. At the last minute they are saved by the Japanese authorities who defeat the insurgents. (Signs of their fierce gun battles are showcased in the Korean newspaper advertisements in Figure 5.) The border officers’ loyalty to the Empire offers a further example of naisen ittai, and the lengths to which they were prepared go to as a way of demonstrating their unity with Japan.

Most of the dialogue in Suicide is in Japanese, even when the Chinese restaurant owner converses with his son. Korean is heard only momentarily, when Korean characters are asked to use their native tongue.18 Various details reinforce the reality that languages other than Japanese are discouraged—for example, signs beside a phone and in a classroom that read, “Use only the national language.” Clearly, the male characters in this propaganda vehicle have been thoroughly assimilated.

Suicide entertained sizable audiences in Korea, earning a reported ¥97,148 (approximately $22,638 U.S. dollars) from screenings in Seoul, Pyongyang, and Pusan (Sakuramoto 1983: 190). Judged by its box office takings, the film was a relatively successful attempt to introduce militaristic propaganda into the action–adventure and melodrama genres that had been popular before the wholesale ban placed on films imported from the U.S. and the Allied countries. Simply put, audiences at the time had few films to choose from. Suicide set out the case for a united front by Koreans while serving as a military recruiting tool for the KCG. Against this background, the film suggests that ordinary Korean men can be transformed into loyal heroes of the Empire, while also praising Korean women for their sacrifices (including the willingness of mothers to kill their babies and themselves) in the service of the war-preparation effort. It also makes the point that mobilizing every Korean citizen, and indeed the entire Empire, was vital for Japan to win the war.

For Korean filmmakers, collaborative pathways such as those pursued in the production of Angels, Spring, and Suicide – including theways in which these films portrayed their characters – were critical for avoiding censorship in Korea, which had become much more restrictive even before the ratification of the Korean Film Law in 1940. Such an approach improved their chances of gaining approval to exhibit a Korean film in Japan, although this was an even harder task than passing the local censor. Thus, after 1937, the film industry in Korea was rapidly being transformed from a cinema scene dominated by commercial entertainment films to one shaped by the political, economic and social imperatives of Japan’s hegemonic agenda. The promulgation of the Korean Film Law in 1940 only hastened the process. The new law removed what little autonomy Koreans had enjoyed in an industry already dominated by Japanese studios.

Concluding Discussion

This article has sought to demonstrate the significance of film in the development and implementation of Japan’s wartime hegemony in the Korean context. The aim here has been to show how key concepts of hegemonic theory such as Gramsci’s notions of commonsense, good sense and the ethico-political moment help us understand and apply the workings of hegemony – especially in gendered terms – through one of the most significant hegemonic mechanisms: film.

The three representative wartime filmsdiscussed above can be seen as part of a film industry that assumed the role of a broad mechanism designed to embed the ethic of naisen ittai deep in Korean culture, with the aim of inspiring Koreans of all ages (but primarily male students) to offer their hearts, minds, and bodies in the service of the Empire. While the Japanese language policy in schools and the training of Koreans literate in Japanese were important aspects of the cultural assimilation policy of the early 1940s, the film industry was crucial to the achievement of this goal, with local Korean audiences exceeding 20 million viewings in 1940 alone.xix Each film showcases some of the shared hegemonic values of the time, but played in a different key. In their various ways, these three productions exemplify the level of uncertainty in the industry and the subsequent difficulties, practical and ideological, that individual filmmakers undoubtedly experienced.

Although the propaganda messages in these films was overt, today readers may wonder whether (both Japanese and Korean) audiences saw Choi and other Korean filmmakers as mouthpieces for assimilationist propaganda that attempted to re-direct Koreans away from thoughts of rebellion and independence and toward the imperial ideology of naisen ittai. In short, the late colonial-era films discussed here attempt to portray a milieu that minimizes the cultural differences between Korea and Japan – not by blending the culture of the two nations indiscriminately, but by using the hegemonic strategy of enfolding Korea into Japan on cultural, intellectual, and practical levels. This article has extended this thesis by showing how gender – and, in particular, contemporary masculinities – operated to facilitate the transformation and incorporation of Korean “commonsense” into Japanese “good sense”.

As only 12 of the 51 films produced in Korea during the late colonial period survive, we may never know the proportion of films that embodied the propaganda message that all would be well so long as Koreans followed Imperial directives—chiefly volunteering for the war effort. Yet, based on their detailed descriptions in Japanese and Korean film periodicals of the time, most of these films envisaged a new world order where, as a result of unbending loyalty to the Emperor’s will, there would be full cultural integration between Japanese and Koreans.

However, despite commitment at the highest levels, the authorities in Korea struggled to implement a genuine “ethico-political moment,” as is evident in aspects of the films discussed above; in particular, the ethic of naisen ittai remained in Gramsci’s space of “unstable equilibria.” The linguistic, class, ethnic and cultural distinctions between the two countries persisted despite the imposition of a uniform national language. On paper, Korea and Koreans had been integrated into the Imperial family and were treated as equal to Japan and the Japanese. However, as Caprio (2009) argues, Japan’s colonization policy, which aimed for “the unity of Japan and Korea” and “the equality of Japan and Korea,” failed to achieve its goal because it was biased towards conditioning Koreans to become more like Japanese and to assist Japan’s mobilization for war.

Korea’s colonial experience was no doubt replicated elsewhere in Asia, with the details changing according to conditions in the local film industry. It is hoped that the present article will inspire others to explore comparative situations – such as Japanese films in occupied China and Taiwan, French films in Indochina, U.S. films in the Philippines, or British films in India, Singapore, and Malaya. In offering brief analyses of the construction of hegemonic masculinities in three wartime films, we are aware that only the surface of a complex and pervasive subject has been scratched – in a field that needs further cultivation.

Brian Yecies is Senior Lecturer in Cultural Studies at the University of Wollongong and author of Korea’s Occupied Cinemas, 1893-1948, New York: Routledge, 2011 (with Ae-Gyung Shim); and The Changing Face of Korean Cinema, 1960-2015, New York: Routledge, forthcoming (with Ae-Gyung Shim).

Richard Howson is a Senior Lecturer and Discipline Leader for Sociology, Cultural Studies and Science Technology Studies at the University of Wollongong and author of the monographs Challenging Hegemonic Masculinity (2006), the forthcoming Sociology of Postmarxism and is co-editor of the volumes Hegemony: Studies in Consensus and Coercion (2008), Migrant Men (2009) and the forthcoming Engaging Men in Gender Equality.

Recommended citation: Brian Yecies and Richard Howson, “The Korean ‘Cinema of Assimilation’ and the Construction of Cultural Hegemony in the Final Years of Japanese Rule,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 11, Issue 25, No. 4, June 23, 2014.

References

Anderson, Joseph L., and Donald Richie. 1982. The Japanese Film: Art and Industry. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press.

Baskett, Michael. 2008. The Attractive Empire: Transnational Film Culture in Imperial Japan. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

Caprio, Mark. 2009. Japanese Assimilation Policies in Colonial Korea, 1910-1945. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Chung, Chonghwa. 2012. “Negotiating Colonial Korean Cinema in the Japanese Empire: From the Silent Era to the Talkies, 1923–1939.” Translated by Sue Kim. Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review E-Journal, 5, Available here.

Connell, Raewyn. 1995. Masculinities. Cambridge, Polity Press; Sydney, Allen & Unwin; Berkeley, University of California Press.

Connell, Raewyn and Jim Messerschmidt. 2005. “Hegemonic Masculinity: Rethinking the Concept.” Gender & Society 19(6): 829-859.

Corkin, Stanley. 2000. “Cowboys and Free Markets: Post-World War II Westerns and U.S. Hegemony.” Cinema Journal 39(3): 66-91.

Cumings, Bruce. 1997. Korea’s Place in the Sun: A Modern History. New York: W.W. Norton.

Dong, W. 1973. “Assimilation and Social Mobilization in Korea: A Study of Japanese Colonial Policy and Political Integration Effects,” in Andrew C. Nahm (ed.), Korea Under Japanese Colonial Rule. Kalamazoo: The Center for Korean Studies – Institute of International and Area Studies, Western Michigan University, 146-182.

Eckert, C. J. 1991. “Class Over Nation: Naisen Ittai and the Korean Bourgeoisie,” in Offspring of Empire: The Koch’ang Kims and the Colonial Origins of Korean Capitalism, 1876–1945. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 224–52.

Gerteis, Christopher. 2007. “The Erotic and the Vulgar: Visual Culture and Organized Labor’s Critique of US Hegemony in Occupied Japan”. Critical Asian Studies, 39(1): 3-34.

Government-General of Tyosen (Chosen). Annual Report on Administration of Tyosen, 1937–38. Foreign Affairs Department (eds.) Tokyo: Toppau Printing Co., 1938.

Gramsci, A. 1971. Selections from the Prison Notebooks. London: Lawrence and Wishart.

Gunning, Tom. 1986. “The Cinema of Attraction: Early Film, Its Spectator and the Avant-Garde.” Wide Angle 8(3/4): 63-70.

Harvey, D. 2005. A Brief History of Neoliberalism, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

High, Peter B. 2003. The Imperial Screen: Japanese Film Culture in the Fifteen Years’ War, 1931–1945. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Howson, R. & Smith, K. 2008. “Hegemony and the operation of consensus and coercion.” In Howson, R. & Smith, K. (Eds.), Hegemony: Studies in Consensus and Coercion. New York: Routledge, 1-15.

Kim Jong-won. 2003. The Dictionary of Korean Film Directors (Hanguk Yeon ghwa Gamdok Sajeon). Seoul: Kookhak Jaryowon.

Kim, Kyung Hyun. 2004. The Remasculinization of Korean Cinema. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Kwon, N. A. 2012. “Collaboration, Coproduction, and Code-Switching: Colonial Cinema and Postcolonial Archaeology.” Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review E-Journal, 5, Available here.

Lee Young-il. 2004. History of Korean Cinema, 2nd edition (Hanguk Yeonghwa Jeonsa). Seoul: Sodo.

Lindstrom, S.F. 16 January 1937. “Nationalism Reported Making Japan Tight Market for Films.” Motion Picture Herald. 33.

Min, Eungjun (2003). “Political and Sociocultural Implications of Hollywood Hegemony in the Korean Film Industry: Resistance, Assimilation, and Articulation”. In Lee Artz & Yahya R. Kamalipour (Eds.), The Globalization of Corporate Media Hegemony. Albany: SUNY Press. 245-261.

Mizuno, Naoki. 2012. “A Propaganda Film Subverting Ethnic Hierarchy?: Suicide Squad at the Watchtower and Colonial Korea.” Translated by Andre Haag. Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture ReviewE-Journal, 5, Available here.

Ōta Tuneya. May 1938. “The Prospect of the Korean Film Industry (Chōsen Eigakai No Tenbō).” Kinema Junpō. 12–13.

Rhee, M. J. 1992. “Language Planning in Korea under the Japanese Colonial Administration,

1910–1945.” Language, Culture and Curriculum 5(2): 87–97.

Robinson, M. E. 1988. Cultural Nationalism in Colonial Korea, 1920–1925. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Sakuramoto T. 1983. “Korean Film During the 15 Year War—Korea in a Transparent

Body.” Kikan Sanzenri 34 (1983): 184–191.

Semati, M. Medhi and Patty J. Sotirin, 1999. “Hollywood’s Transnational Appeal: Hegemony and Democratic Potential?” Journal of Popular Film and Television 26(4): 176–88.

Shin, Byungju, and Gon Namkung. 2008. “Films and Cultural Hegemony: American Hegemony ‘Outside’ and ‘Inside’ the ‘007’ Movie Series.” Asian Perspective 32(2): 115-43.

Shin, Gi-Wook and Michael Robinson, eds. 1999. Colonial Modernity in Korea. Cambridge, MA and London: Harvard University Press.

Yecies, B. 2004.“Projecting Sounds of Modernity: The Rise of the Local ‘Talkie’ Technology in the Australian Cinema, 1924-1932.” Australian Historical Studies, 35(123): 54-83.

Yecies, B. 2005. “Systematization of Film Censorship in Colonial Korea: Profiteering from Hollywood’s First Golden Age, 1926–1936,” Journal of Korean Studies 10(1): 59–84.

Yecies, B. 2008. “Sounds of Celluloid Dreams: Coming of the Talkies to Cinema in Colonial Korea.” Korea Journal 48(1): 16-97.

Yecies, B. and A. Shim. 2011. Korea’s Occupied Cinemas, 1893-1948, Routledge Advances in Film Studies. New York: Routledge, 2011.

Select Filmmography of Colonial-era Films

(including films known to exist at the Korean Film Archive)

Angels on the Streets (Ie naki tenshi, aka Homeless Angel, Choi In-kyu, 1941). 2007. The Past Unearthed: Collection of Feature Films in the Japanese Colonial Period (DVD). Seoul: Korean Film Archive.

Children of the Sun (1944) – no known copy extant.

Dear Soldier (aka Mr. Soldier, Bang Han-joon, 1944). 2009. The Past Unearthed: The Third Encounter (DVD). Seoul: Korean Film Archive.

Fisherman’s Fire (An Cheol-yeong 1938). 2008. The Past Unearthed: The Second Encounter Collection of Chosun Films in the 1930s (DVD). Seoul: Korean Film Archive.

I Will Die Under My Flag (Kim Hwa-rang, 1939). Available on DVD only at the Korean Film Archive.

Love of Their Neighbors (Okazaki Renji, 1938). Available on film only at the Korean Film Archive.

Military Train (aka Troop Train, Seo Gwang-je, 1938). 2008. The Past Unearthed: The Second Encounter Collection of Chosun Films in the 1930s(DVD). Seoul: Korean Film Archive.

Portrait of Youth (Toyota Shiro, 1943). Available on DVD only at the Korean Film Archive.

Sons of the Sky (1945) – no known copy extant.

Spring in the Korean Peninsula (Hantō no haru, Lee Byeong-il, 1941). 2007. The Past Unearthed: Collection of Feature Films in the Japanese Colonial Period (DVD). Seoul: Korean Film Archive.

Straits of Chosun (Park Ki-chae, 1943). 2007. The Past Unearthed: Collection of Feature Films in the Japanese Colonial Period (DVD). Seoul: Korean Film Archive.

Story of Sim Chung (An Seok-yeong, 1937). VOD via the Korean Film Archive website. Available here.

Suicide Squad at the Watchtower (Bōrō no kesshitai, aka Suicide Troops of the Watchtower, Imai Tadashi, 1943). VOD (in person) at the Korean Film Archive library room, Seoul.

Sweet Dream (aka Mimong, Yang Ju-nam, 1936). 2008. The Past Unearthed: The Second Encounter Collection of Chosun Films in the 1930s (DVD). Seoul: Korean Film Archive.

Tuition (aka Tuition Fee, Choi In-gyu and Baek Un-haeng) 1940 – no known copy extant.

Volunteer (Ahn Suk-young, 1941). 2007. The Past Unearthed: Collection of Feature Films in the Japanese Colonial Period (DVD). Seoul: Korean Film Archive.

Vow of Love (Choi In-gyu, 1945). VOD via the Korean Film Archive website. Available here.

You and Me (Heo Yeong, 1941) Available on film only at the Korean Film Archive.

Notes

1 The authors acknowledge the support of the Korea Foundation, the Academy of Korean Studies, and the Australia-Korea Foundation, which made it possible to conduct archival and industry research for this project. Special thanks goes to Ae-Gyung Shim for her research assistance, and to the referees for their invaluable comments.

2 For a detailed discussion of naisen ittai, see Eckert (1991: 224–252).

3 The phrase “cinema of assimilation” is a play on Tom Gunning’s “cinema of attraction[s]” (1986), which refers to the response of early cinema audiences to the spectacle offered by public film screenings. Our use of the term “assimilation” refers to social proximity and the outcome of a hegemonic process rather than to a technique involving the repeated use of close-up shots. This fits neatly with the sociological definition of assimilation – the adoption of values and patterns of behavior of the majority or authoritarian group by the minority or colonized group.

4 For example, a keyword search of the Journal of Popular Film and Television from 1997 to 2013, for example, returns 77 articles where the term hegemony is used – an average of 4 to 5 articles in each volume that employs the concept, across a range of issues and genres.

5 Prior to this, Korean cinema had been dominated by Hollywood films – surprisingly, to a greater extent than in Japan. The visually dazzling Hollywood feature films that stimulated audiences in Korea during the early-to-mid 1930s included: The Last Flight (1931), The Crowd Roars (1932), Winner Take All (1932), I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang (1932), Tiger Shark (1932), Frisco Jenny (1932), Central Air Port (1933), Footlight Parade (1933), Gold Diggers of 1933 (1933), Son of a Sailor (1933), The Little Giant (1933), Captured! (1933), 42nd Street (1933), and Fashions of 1934 (1934). See Yecies 2005, and Yecies and Shim 2011.

6 As reported in the Motion Picture Herald, a major U.S. trade magazine, Japan had begun fostering “a situation whereby all business enterprises, including pictures, other than those in the control of the Japanese themselves, are made to feel painfully out of place, with merciless native competition, backed up by canny government legislation…” See Lindstrom 1937: 33.

7 The practice of distributing free tickets to Koreans as a marketing strategy to boost their patronage of Japanese films began around 1936 (Eiga Hyōron July 1941: 54–60). The KCG used such promotional strategies to increase the numbers of Koreans attending screenings of Japanese and other officially sanctioned films produced in Korea.

8 Quoted from a speech by Governor-General Minami Jirō delivered to Korea’s thirteen provincial governors in April 1937. (See Government-General of Tyosen 1938: 227.)

9 Available at the Korean Film Database.

10 Ironically, the strict Government-General Law No. 82, ratified on 7 August 1934, stimulated Korean film production because Korean films were now categorized as “domestic” products. At the same time, exploitative film promotions and other activities aimed at attracting audiences both inside and outside the cinema environment began winding down.

11 Between 2004 and 2005, the Korea Film Archive discovered prints of Angels on the Streets (1941) and Spring in the Korean Peninsula (1941) – along with Sweet Dream (1936), Military Train (1938), Fisherman’s Fire (1939), Volunteer (1941), and Straits of Korea (1943) – in the Chinese Film Archives in Beijing. Previously, Suicide Squad at the Watchtower (1943) was one of only three colonial-era feature films – along with Figure of Youth (1943), and Love and Commitment (1945) – unearthed in 1989 in the Tōhō Studio archives in Japan.

12 As a result of the critical acclaim garnered by Angels, Choi In-gyu developed a reputation for his use of a realist aesthetic in his portrayal of contemporary life. In 1940, he had directed Tuition (aka Tuition Fee), a film based on an award-winning essay by a primary school pupil telling the story of a poor student whose friends helped him to pay his tuition fees. Despite (limited) opportunities to work alone, that is, with all-Korean crews, Choi actively participated in the new production system by directing explicit propaganda films such as Children of the Sun (1944), Vow of Love (1945), and Sons of the Sky (1945). The two later filmswere “message films” designed to educate young male Koreans about military service and recruit them into the armed forces, while also persuading them to embrace loyalty to the Empire.

13 Rookie director Lee Byeong-il had gained valuable experience working at the Nikkatsu Studios in Tokyo between 1934 and 1940. Returning to Korea, he created the Myeongbo Film Company; Spring was the company’s first film. (Kim 2003: 456–457)

14 Based on a popular 17th-century pansori theater performance, in which a singer and a drummer engage audiences through music and storytelling, Chunhyang reflected the intimacies and uniqueness of Korean culture. The film tells the love story of a noble scholar and Chunhyang, the daughter of a gisaeng – traditionally regarded as belonging to the lowest social class – to whom he is secretly married. The love story unfolds against a narrative involving a corrupt official and a covert envoy sent by the king to inspect the regional bureaucracy. Seduced and threatened by the corrupt official, the heroine nevertheless maintains her fidelity to her husband. Finally, the scholar reveals his true identity, saves Chunhyang and punishes the offending official for his maladministration – thus confecting a happy ending centered on the idea of loyalty.

15 At the same time,Chunhyang also revealed the dire conditions faced by the domestic film and audio industries. Thecharacters’ aims – and, indeed, the messages carried by this film – mirror thetechnological challenges faced by film workers before the consolidation of the local film industry and the subsequent adoption of modern production methods used by Japanese filmmakers.

16 The large-scale reorganization of the industry in Korea occurred with the formation of the consolidated Chosun Film Distribution Corporation in April 1942 and the Chosun Film Production Corporation in September 1942. This major development enabled the occupying power to increase its draconian control over the film industry and to harness filmmaking as a key tool for spreading Japanese “national” culture.

17 Mizuno (2012) also comments on the strong role of the female medical student (played by Kim Shin-jae, who played an aspiring doctor in Angels), in addition to detailing the film’s production history.

18 A small party scene set in the yard of the police station shows the peaceful atmosphere of the border village in which Koreans and Japanese live in harmony together. Once the alcohol is flowing, the group of men begins singing in Japanese. Following this, a Japanese policeman asks one of his Korean colleagues to sing a traditional Korean folk song, at which point a local man launches into a Korean-style dance.

19 This was a significant figure given that the entire population of Korea, including foreign expatriates, was 24 million (Samcheolli January 1941: 163).