Anyuan: Mining China’s Revolutionary Tradition (University of California Press, 2012) seeks to answer the complex question of why the Chinese Communist revolution took such a different path from its Russian prototype. It suggests that a key distinction between the two revolutions lay in the Chinese Communists’ creative development and deployment of cultural resources – during their rise to power and afterward. Skillful “cultural positioning” and “cultural patronage” on the part of Mao Zedong, his comrades, and successors helped to construct a polity in which a once-alien Communist system came to be accepted as familiarly “Chinese.”

The book traces this process through a case study of the Anyuan coal mine on the Jiangxi-Hunan provincial border, where Mao and other pioneers of the Chinese Communist Party – most notably Li Lisan and Liu Shaoqi – mobilized an influential labor movement at the very beginning of their revolution.

|

Chapter Two, “Teaching Revolution,” is reproduced here with permission from the University of California Press. It focuses on these early mobilization efforts, which resulted in the influential Anyuan Great Strike of 1922 and led to Anyuan’s status as the major center of Chinese Communist labor organizing for the following three years.

|

Known in that period as “China’s Little Moscow,” Anyuan served then and later as a touchstone of political correctness that over time came to symbolize an authentically Chinese revolutionary tradition. The book examines the contested meanings of that tradition throughout the history of the People’s Republic down to the present, as Chinese debate their revolutionary past in search of a new political future.

|

Elizabeth J. Perry is Henry Rosovsky Professor of Government at Harvard University and Director of the Harvard-Yenching Institute and author of ANYUAN: Minging China’s Revolutionary Tradition. Other recent books include Mao’s Invisible Hand: The Political Foundation of Adaptive Governance in China; Patrolling the Revolution: Worker Militias, Citizenship, and the Modern Chinese State; and Chinese Society: Change, Conflict and Resistance.

Recommended citation: Elizabeth J. Perry, ANYUAN: Mining China’s Revolutionary Tradition, The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol 11, Issue 1, No. 4, January 14, 2013.

Chapter Two – Teaching Revolution

The Strike of 1922

Despite an accumulation of excellent scholarship on the Chinese Communist revolution, we are still hard-pressed to offer a compelling answer to a question that goes to the heart of explaining the revolution’s success: How did the intellectuals who founded the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) manage to cultivate a large and loyal following among illiterate and impoverished peasants and workers, a stratum of the populace so distant from themselves?

One might ask a similar question of many revolutions, of course, in light of the leadership role that intellectuals have typically played in nationalist and Communist movements around the world.1 It seems especially perplexing in the case of China, however, where Confucian precepts had long fostered a stark distinction between mental and manual labor. The superior status of the literati, celebrated in Mencius’s dictum that “those who labor with their brains rule over those who labor with their brawn,” contributed to a huge social and political distance between the “cultured” and “uncultured.” Moreover, although the iconoclastic New Culture Movement of the early twentieth century inspired many pro-gressive Chinese intellectuals, Mao Zedong among them, to repudiate Confucianism in favor first of anarchism and then of Marxism-Leninism, among ordinary workers and peasants these radical new ideas had made few inroads. Nationalism (as opposed to xenophobia) was also initially an ideology largely confined to the educated elite.2 For most Chinese, both the nation-state and the social classes that supposedly comprised it were still unfamiliar concepts.

As we saw in the case of the failed Ping-Liu-Li Uprising (Chapter 1), an alliance between would-be revolutionaries and their purported fol- lowers was far from a foregone conclusion. Fertile ground as Anyuan was for collective protest, preexisting solidarities and mentalities were not easily converted to alternative political purposes. Furthermore, the Communists were determined from the start to introduce new modes of grassroots organization. The founding resolution of the Chinese Communist Party, adopted in Shanghai in July 1921, began as follows: “The basic mission of this party is to establish industrial unions.”3 The resolution went on to explain the means by which this mission was to be accomplished, stressing the key role of education: “Because workers’ schools are a stage in the process of organizing industrial unions, these sorts of schools must be established in every industrial sector. . . . The main task of the workers’ schools is to raise workers’ consciousness, so that they recognize the need to establish a union.”4

In emphasizing proletarian education, CCP policy drew both upon the precedent of the Russian Revolution (where schooling for workers was an element of Bolshevik strategy) and upon contemporary experiments within China.5 At the time, Y. C. James Yen’s Mass Education Movement, Huang Yanpei’s Vocational Education Campaign, and Liang Shumin’s Rural Reconstruction Movement were part of a growing number of high-profile initiatives, intended to foster popular literacy and provide practical training, which had captured the imaginations of many concerned young Chinese intellectuals, including a number of future Communists.6 Equally significant for the ultimate success of the Chinese Communists’ pedagogical effort was the central place that education had long occupied in Chinese popular and political culture. A belief in the educability of all human beings, and an attendant obligation on the part of the intel- ligentsia to provide moral instruction to those with less education, were deeply ingrained precepts of both ancient and modern Chinese thought.7 In the late imperial period, the civil service examination system, which rewarded outstanding scholars with official government position as well as responsibility for the moral cultivation of those living under their rule, was the institutionalized expression of this philosophy.8 Seen as the sur- est path to political and economic success for families who could afford it, education for centuries had been highly prized as a means of upward mobility.9 In this particular context, “teaching revolution” would prove to be an unusually persuasive mode of popular mobilization.

When Communist study groups first formed in Beijing and Shanghai in the wake of the 1919 May Fourth Movement, their members dedicated themselves to the project of educating workers. More than a year before the formal founding of the CCP in July of 1921, Communist students from Beijing had already established a school for workers at Changxindian, a terminus along the Jing-Han Railway. Within a few months, the railroad worker-students organized a labor union that they euphemistically called a “workers’ club” (gongren julebu) to avoid arousing suspicion among the local authorities. Soon Communist activists in Shanghai followed the Changxindian model, introducing first schools and then unions among textile workers in the city.10 This linkage between mass education and grassroots organization was critical to the success of the Communist revolutionary effort.

Targeting Anyuan

Mao Zedong, having attended the founding congress of the Chinese Com- munist Party in Shanghai before returning to his native Hunan province to head a branch of the CCP-sponsored Labor Secretariat in Changsha, was eager to follow the party’s prescribed recipe for proletarian mobilization. At the time, however, factories in Hunan were generally small and scattered, and the nascent labor movement was under strong anarchist influence.11 The nearby site of Anyuan, located just across the border in Jiangxi’s Pingxiang County, was virgin territory. Its coal mine and railroad had a combined and concentrated labor force of over ten thousand workers, making it the largest industrial enterprise in the area. The region’s reputation for rebelliousness rendered it of particular interest.

In fact, Mao Zedong had been attracted to the revolutionary potential of Pingxiang even before the first CCP congress. In November 1920 he traveled there for a week to enjoy the refreshing mountain scenery and investigate local conditions. At the time, Mao was teaching Chinese literature at the First Normal School in Changsha to make ends meet, but most of his energy was already directed toward social activism. Although Mao seems not to have visited the Anyuan coal mine on his initial trip to Pingxiang, he was clearly taken by the possibilities for popular mobiliza- tion in this area. A few months earlier, thousands of Pingxiang peasants had engaged in a series of rowdy “eat-ins” at landlords’ homes; in one instance, the peasants set fire to a landlord’s house, incinerating several of his family members. Shortly after his Pingxiang journey, Mao wrote a stirring piece entitled “Open Letter to the Peasants of China” for the journal Communist Party in which he enthusiastically referred to the recent uprising: “This year’s events in Pingxiang are inklings of dawn for the awakening of the Chinese peasantry. . . . It is exactly like the first rays of sunshine from the east after a pitch black night. . . . From birth you have had to work like beasts of burden. . . . You just need to imitate the peasants of Pingxiang. . . . Of course Communism will come to your aid. . . . So long as you follow the lead of the peasants of Pingxiang, Communism will release you from all suffering so that you may enjoy unprecedented good fortune.”12

Mao’s budding interest in the power of the peasantry notwithstanding, at this early stage in its history the newly established Chinese Communist Party was oriented toward proletarian—rather than peasant— mobilization. Shortly after returning from the founding party congress, Mao Zedong made another trip to Pingxiang, this time for the express purpose of investigating conditions at the Anyuan coal mine.13 Mao embarked on his fact-finding mission in a period, in the fall of 1921, when the mine was experiencing severe economic difficulties as a result of a dramatic drop in demand for coal at the end of the First World War. To make matters worse, battling warlords had cut the critical Zhuping rail line and exacted a toll on the labor force through the forcible conscription of miners into their makeshift armies.14 That the moment was ripe for agitation was clear from the fact that several educated Hunanese railroad workers had taken it upon themselves to write to the Communist Labor Secretariat, requesting that it send someone to Anyuan to help organize a labor movement.15

To make contact with the miners, however, required a proper introduc- tion. On his initial visit, Mao stayed at the home of a man from his home county of Xiangtan, a distant relative by the name of Mao Ziyun, who happened to be employed as a supervisor at the coal mine. Renowned for his skill in using Chinese herbal medicine to heal the painful throat ailments that afflicted many miners, Mao Ziyun had befriended a good number of Anyuan workers in the course of practicing his curative techniques. Living in a comfortable house just outside the main entrance to the mine, Mao Ziyun was well situated to assist his visiting relative from Hunan. After being introduced to several miners at his kinsman’s home, Mao Zedong ventured down into the coal pits.

According to later interviews conducted with miners who encountered Mao Zedong during this visit, Mao arrived at Anyuan carrying a Hunan umbrella made of oiled paper and dressed in a long blue Mandarin gown of the sort worn by teachers at the time.16 Mao’s scholarly demeanor left a deep impression upon the workers, who recalled being surprised by the peculiar sight of a privileged intellectual anxious to interact with lowly coal miners. The Confucian separation between mental and manual labor rendered such a cross-class encounter unusual, to say the least. The miners were not the only ones struck by the cultural distance between themselves and the young teacher from Changsha. More than thirty years later, when Mao Zedong hosted a banquet for newly appointed members of the Central Military Affairs Commission, several of whom were for- mer Anyuan workers, he reminisced about his first visit to the coal mine. A participant at the 1954 banquet later reported:

Chairman Mao recalled his youthful effort to develop the labor movement in Anyuan, Pingxiang. Chairman Mao said, “In those years, after receiving some education in Marxism, I imagined I was a revolutionary. But as it turned out, when I got to the coal mine and began to interact with the workers, because I was still a student at heart and a teacher in style, the workers wouldn’t buy it. We didn’t know how to proceed. Looking back now, it was pretty amusing. I spent the whole day just walking back and forth along the railroad tracks trying to figure out what to do. . . . Only when we dropped our pretentious airs and respected the workers as our teachers did things change. Later we chatted with the workers, sharing our genuine feelings, and the worker comrades gradually began to get close to us, tell- ing us what was really on their minds.”17

Despite the initial cultural gulf that separated him from his targeted constituency, Mao, thanks to his rural upbringing and colloquial dialect, was able to converse easily with the workers—most of whom shared his Hunan origins—and by week’s end he had shed his scholar’s gown in favor of a pair of trousers, which were more suitable for forays down into the mining pits.

In his exploratory conversations with the Anyuan workers, after a few inquiries about their difficult working and living conditions, Mao Zedong turned to the topic of education. Since Mao was supporting his revolu- tionary activities by teaching in the mass education movement in Hunan, it must have seemed quite natural for him to direct the discussion toward this issue. Although the establishment of schools was official CCP policy, in accordance with the Russian revolutionary recipe, it resonated espe- cially strongly in a cultural milieu where education had long been valued as the pathway to social mobility. A miner who met with Mao Zedong on his maiden visit to Anyuan later recalled Mao’s introduction of this topic (referring, anachronistically, to Mao as “Chairman”):

The Chairman asked us whether we went to school. I answered that we weren’t even able to afford to eat, so how could we possibly manage to take classes. The Chairman asked: what if education were free? I said that if it didn’t require any money of course people would want to study. I asked the Chairman when we could get started. He pointed out that the year was almost over, but promised that the next year he would send someone to open a school. The following day I ran into the Chairman again and he repeated that he would send somebody in the new year to open a school for us.18

In December 1921 Mao Zedong returned to Anyuan to make concrete plans for establishing a school at the mine.19 He took with him three other educational activists from Hunan, including the energetic Li Lisan, who had recently returned from two years of studies in France and had joined the Communist Party in Shanghai before heading home to Hunan. In addition to Mao and Li Lisan, the advance team was composed of Song Yousheng, a teacher at a Hunan elementary school, and Zhang Liquan, a cadre in the Liaison Department of the Hunan Labor Secretariat who edited the secretariat journal, Labor Weekly, while teaching at the Hunan Jiazhong Industrial School in Changsha. The four young men stayed for several days in a small inn near the mine, inviting workers to drop by for a chat as soon as they got off work.20

Initially, the members of the Anyuan workforce most receptive to Communist overtures were railway workers, whose own educational and cultural backgrounds facilitated communication with the young intellectuals from across the border. Among the most enthusiastic was the chief engineer of the Zhuping railway, a fellow Hunanese by the name of Zhu Shaolian, who had graduated from the railroad academy in Hubei before being assigned to the job at Anyuan. When quizzed by the visitors from Hunan about their most pressing concerns, Zhu and his fellow workers reiterated what the miners had previously told Mao Zedong, complaining that their children were unable to attend school because of the prohibitive expense. Mao reportedly replied, “Suffering is caused by lack of knowl- edge. We are not only going to open a school for workers’ children. We will also open a school to educate workers.”21

Educating Anyuan

Soon after the group had returned to Hunan, Mao Zedong informed Li Lisan of his decision to send Li back to Anyuan to make good on his pedagogical pledge. Mao impressed upon Li Lisan the importance of dealing sensitively with prevailing conditions and customs. In particular, he cautioned Li about the power of the Red Gang in light of the secret society’s formidable grip on the workers. Stressing that the “reactionary ruling forces” and “dark social environment” at the mine made it impossible to undertake open revolutionary mobilization, Mao suggested a more oblique approach. First on Li’s agenda would be to establish schools for workers and their children. Only after having earned the miners’ trust as a respected teacher would Li be in a position to organize them for overtly political purposes.22

The first resolution of the newly founded CCP, as we have seen, gave the official party stamp of approval to workers’ education as a stepping-stone toward unionization. Mao’s specific instructions to Li Lisan reiterated these guiding principles. Li recalled many years later that, although Mao Zedong had chosen Anyuan because of its exceptional revolutionary potential, he warned the impatient young firebrand against premature radicalism. Instead Li was to proceed by stages, beginning with a focus on public education:

In November 1921, when Comrade Mao Zedong sent me to Anyuan to undertake the labor movement, he already had a clear idea of how to begin work among the workers, how to gradually organize so as to advance toward struggle. He told us . . . that it wouldn’t be easy to launch a revolutionary movement, and he said we must first take advantage of all legal opportunities and focus on open activities to get close to the labor movement and identify outstanding elements among the workers, gradually disciplining and organizing them be- fore establishing a [Communist] party branch. He wanted us to oper- ate under the banner of mass education, going to Anyuan with an introduction from the Hunan branch of the Mass Education Society.23

Only twenty-two years of age at the time, Li Lisan was an ideal choice to assume the role of Anyuan schoolteacher. His father was an imperial degree holder from nearby Liling County (less than thirty miles due west of Anyuan, in Hunan Province) who offered instruction in the Confucian classics, and Li Lisan himself—at his father’s insistence—had taught at an elementary school in his native Liling before heading off to Beijing and France for additional studies. Within weeks of his return from Lyons in late 1921, Li Lisan traveled to Beijing to see one of his old middle school classmates from Hunan, Luo Zhanglong, who was then directing the new Communist-sponsored school for railroad workers at the Changxindian station on the Jing-Han Railway. Impressed by what he witnessed, Li was anxious to replicate Luo’s pioneering efforts in another industrial set- ting. The fact that many of the Anyuan miners hailed from Li Lisan’s home county of Liling (as well as from Mao Zedong’s home county of Xiangtan) was an additional attraction for the would-be labor organizer.

Armed, at Mao Zedong’s suggestion, with a letter attesting to his educational credentials written by Li Liuru, the deputy director of the Hunan branch of the Mass Education Society, Li Lisan returned to Anyuan under the guise of an aspiring schoolmaster. Although the idea of worker schools derived from the Russian experience, Li’s method of implementa- tion drew self-consciously on his own cultural traditions. Upon learning that the magistrate of Pingxiang County was a top-ranked Confucian degree holder who adamantly opposed written vernacular language, Li Lisan put his own classical training to use by composing in his best literary Chinese a flowery petition requesting official permission to open a school at Anyuan.

Like Mao Zedong before him, Li Lisan relied upon the introductions of relatives to gain local access. Thanks to the help of a friend of Li Lisan’s father, a Liling man by the name of Xie Lanfang who happened to be the director of the Anyuan chamber of commerce, Li Lisan’s petition was delivered directly to the county magistrate. Delighted by the classical style and fluid calligraphy of Li’s writing, the Pingxiang magistrate invited the young scholar from Liling to meet in person to discuss his pedagogical proposal. So pleased was the conservative magistrate by Li Lisan’s Confucian-sounding pronouncements about the contribution of education to the improvement of public ethics that he immediately agreed to issue an official proclamation in support of the proposed new school. The proclamation quoted verbatim from Li’s petition: “help- ing workers to increase their knowledge in order to promote virtue.”24 Unbeknownst to the magistrate, Confucian rhetoric would pave the way toward Communist revolution.

The moralistic magistrate, who hailed from Hubei, hoped that Li Lisan’s pedagogical efforts might help to improve public civility in the notoriously roughneck town of Anyuan, where brothels, opium dens, and gambling halls far outnumbered schools. In this town of eighty thousand inhabitants, the only functioning school, — which was operated by St. James Episcopal Church with some assistance from the mining company (see Chapter 1), charged steep tuition fees in return for a strongly religious regimen of instruction. Enrollment at the church school was largely limited to the children of high-level staff; the sons and daughters of electrical engineers from Shanghai and Guangzhou were especially well represented among the few hundred children fortunate enough to attend. Ordinary workers at Anyuan had little prospect of educational advancement for either them- selves or their children.25 From the magistrate’s (mistaken) perspective, Li Lisan’s proposed school could serve as a Confucian counterweight to the Christian education being dispensed by the local church.

With assistance from Zhuping railway chief engineer Zhu Shaolian and a couple of fellow Hunanese railway workers to whom Mao had previously introduced him, Li Lisan rented the top floor (three rooms) of a house in town for his school, prominently posting the magistrate’s supportive proclamation above the front door. He also put up several announcements around town advertising the new tuition-free educational opportunity. Thirty or forty students, almost all of them the children of railway workers, soon enrolled.26 Li Lisan took advantage of his position as teacher to pay home visits to the children’s parents, thereby becoming acquainted with a number of the workers. Wearing his long Mandarin gown and striding ostentatiously from house to house to drum up additional pupils for his classes, Li acquired the moniker of “itinerant scholar-teacher” (youxue xiansheng) among the locals.27

Although his literati dress and obvious erudition allowed Li Lisan to win the approval of local officials, a crucial first step toward realizing his educational ambitions, he soon revealed that he was no ordinary Confucian teacher. Despite his Mandarin bearing, Li Lisan on evening visits to his students’ families engaged his hosts in animated discussions about the possibility of improving labor conditions through workers’ education, organization, and struggle. Railway workers—who generally had some education—initially proved much more receptive to Li’s message than did the illiterate miners. A group of Hunanese railway mechanics, includ- ing Hubei Railway Academy alumnus Zhu Shaolian (at whose house Li Lisan was living) along with several recent graduates of the progressive Jiazhong Industrial School in Changsha, formed the nucleus of Li Lisan’s coterie. Within a couple of weeks, Li had identified eight potential activists—all but one of them railway workers—whom he persuaded to join him in forming an Anyuan branch of the Socialist Youth League. At Li Lisan’s prompting, the league members (six of whom Li soon tapped to constitute a Communist Party cell) focused on educating fellow workers as their first priority. They converted the rented classrooms, occupied by the workers’ children during the day, into a school for workers at night.28

Starting with a handful of students drawn from the railway machine shop, the night school quickly expanded to enroll several dozen workers. Li Lisan’s dynamic teaching style—which combined basic literacy instruction with revolutionary messages—proved immensely popular. Employing the art of glyphomancy (the deconstruction and recombination of Chinese characters) familiar from secret-society fortune telling, Li Lisan showed how the two characters that combined horizontally to form the term for “worker” (gongren) could be repositioned vertically into a single character meaning “Heaven” (tian). When the workers stood up, he explained, they would enjoy the blessing of Heaven. Li also had a knack for translating abstract concepts into mundane metaphors. Many years later, one of his Anyuan students still recalled the memorable way in which Li had conveyed the importance of proletarian unity: “Once, when Comrade Li Lisan was lecturing about how the workers needed to unite in order to have enough power to struggle against the capitalists, he grabbed a single chopstick along with a bundle of chopsticks as an illus- tration. A single chopstick, he demonstrated, could be broken with one flick of the wrist. When bundled together, however, no single chopstick could easily be broken. This simple example left a profound impression on our thinking.”29 Soon the CCP assigned another young teacher from Hunan, Jiang Xianyun, to handle the classes for children, so that Li Lisan could devote himself to the workers full-time.30 The initial eight or nine worker-students, like the founding members of the Anyuan Socialist Youth League and Communist Party, were predominantly railway mechanics from Hunan who had attended the Jiazhong Industrial School.

The receptivity of Hunanese engineers and mechanics to Communist appeals was not an Anyuan anomaly; in other parts of China as well shared native-place origins and educational backgrounds rendered skilled male workers especially responsive to Communist initiatives.31 But whereas in many Chinese industrial enterprises occupational skill was closely aligned with gender and native-place origin, the situation at Anyuan was rather more complicated. Unlike textile mills or tobacco factories, where unskilled labor was often performed by women migrants who did not speak the local dialect, the Anyuan coal mine was an all-male operation that recruited its haulers and diggers as well as its railway engineers from within the local dialect region. The majority of unskilled miners shared with skilled railway workers a common Hunan provenance. In this they differed markedly from upper-level staff and electrical engineers, who hailed from distant urban centers in Guangdong, Jiangsu, and Zhejiang. The Hunan miners were distinct as well from those miners (a minority, but a significant minority nonetheless) who came from nearby villages in Pingxiang County itself. Despite the strong similarity in language and customs between Pingxiang and Hunan, many locals harbored resentment toward Hunanese incursions into their economy and politics that dated back to the founding of the modern coal mine.

It was obvious to Li Lisan from the outset that success at Anyuan would require substantial support from coal miners, who outnumbered railway workers by nearly ten to one. Despite the railway workers’ educational advantage over miners, their shared dialect and culture facilitated communication and cooperation. Li therefore encouraged the railroad workers—some of whom had Red Gang connections—to reach out to their sworn brothers among the miners. Although he imagined that new Communist-sponsored institutions would eventually supplant the Red Gang’s hold over the workers, Li Lisan realized (as Mao Zedong had warned) that a direct clash with the secret society would be disastrous at this preliminary stage. In order to enroll in Li’s school, therefore, miners were required first to obtain permission from their labor contractors, virtually all of whom were Elder Brother chieftains.32

When Li Lisan first headed into the coal pits to enjoin miners to attend his classes, this bizarre behavior on the part of an intellectual was greeted with sarcastic incredulity: “Is this the Episcopal Church or the Catholic Church? The Red Gang or the Green Gang? Come to spread the gospel or to enlist soldiers?”33 But Li was undeterred by the tendency to inter- pret his revolutionary efforts in terms of more familiar institutions. He persisted, prevailing upon each new student at his night school to recruit several friends, and soon the coterie of worker-students had expanded in both number and diversity. When the sixty enrollees could no longer be accommodated within the space that Li had originally rented, he formed the Educational Affairs Committee—composed of himself and his fellow teacher together with railway engineer Zhu Shaolian and one miner—to oversee the move to a larger facility. Both the school for children and the workers’ night school were relocated to a more spacious building, which housed a newly opened reading room stocked with left-wing periodicals in addition to several classrooms.34

Besides the issue of space, Li faced the problem of securing appropriate instructional materials for his educational activities. The classes for children could make use of basic textbooks that had been compiled previously by the Mass Education Society with the help of the YMCA. These con- tained beginning lessons in reading and arithmetic. More challenging, however, were the textbooks for workers, whose education was intended ultimately to instill revolutionary class consciousness in addition to functional literacy. Li Lisan later recounted how he gradually introduced subversive ideas under the cover of an officially approved curriculum: “The workers’ classes used two types of textbooks. Openly we used the textbooks prepared for mass education. But actually we used materials that we ourselves had edited. At every class we dispensed a bit of basic Marxist-Leninist knowledge, emphasizing that all the world’s wealth had been produced by the working class.”35 The first lesson in the approved thousand-character mass education reader began with the innocuous sentence “One person has two hands; two hands have ten fingers.” The unauthorized materials, by contrast, included lessons in class conflict with telling titles such as “Workers and Capitalists.”36 The combination of conventional textbooks together with unorthodox handouts called for some subterfuge on the part of the students. As one of them recalled, “When Li Lisan first opened the school, I joined. Our text was the thousand-character reader. But his lectures stressed the exploitation and oppression of the workers. Someone stood guard at the classroom door to keep outsiders from eavesdropping. Later on, stencils of Marx’s ideas were handed out for us to study. If outsiders happened to come by, we covered the stencils with the thousand-character reader.”37 Aware of the pressing need for teaching materials, Mao Zedong sent the deputy direc- tor of the Hunan branch of the Mass Education Society, Li Liuru (whose letter of introduction had opened official doors for Li Lisan and whom Mao had just recruited into the CCP) to Anyuan in the spring of 1922 for the express purpose of editing textbooks appropriate for the workers’ school there. After touring the coal pits and dormitories to observe labor and living conditions firsthand, Li Liuru compiled a four-volume series, known as Mass Reader (Pingmin Duben), which introduced students to a rudimentary understanding of Marxism-Leninism.38

Renting classrooms and printing and purchasing textbooks all took money, of course, and obtaining enough funding to underwrite these educational activities posed another challenge for Li Lisan. At first the Anyuan school was financed by the Labor Secretariat in Shanghai and the Hunan branch of the Mass Education Society in Changsha.39 But this dependence upon distant benefactors with more pressing priorities pre- sented obvious disadvantages, and Li again employed Confucian logic on local notables to remind them of the moral benefits of education. Soon the classes were supported by philanthropic contributions from members of the local elite, augmented by nominal fees from the workers themselves. The foreman for construction at the coal mine, a skilled artisan by the name of Chen Shengfang who hailed from Li Lisan’s own native county of Liling, was a particularly generous source of financial assistance.40

Unionizing Anyuan

Just as party policy prescribed, the Anyuan workers’ school served as a springboard for other modes of labor organization. One evening, some of the workers came across a journal article in their school reading room about Shanghai textile workers having recently formed a “club” (a euphe- mism for a labor union) to advance their collective interests. The workers asked Li Lisan whether they might do something similar at Anyuan, a proposal that of course delighted the eager young Communist organizer. After two preparatory meetings, Li Lisan, Zhu Shaolian, and several other workers submitted a petition to the Pingxiang County government requesting official approval to establish a “workers’ club,” which would be restricted to railway workers and miners (and explicitly exclude the com- pany staff). Satisfied with the club’s seemingly innocent motto of “forge friendships, nurture virtue, provide unity and mutual aid, and seek common happiness,” the county magistrate—without consulting the Ping- xiang Railway and Mining Company—readily approved the request.41 The new Anyuan workers’ club preparatory committee, with Li Lisan as its director and railroad engineer Zhu Shaolian as its deputy director, was headquartered in rented space at the Hubei Guild Hall, and the night school classes were moved to this more capacious site.42

Although the introduction of a labor union was a novel development, its organization and operations were evocative of local precedents. As in the Hongjiang hui of the Ping-Liu-Li Uprising (see chapter 1), club members were organized according to a decimal system. Groups of ten (shirentuan) were established in every workshop, with one leader from each workshop responsible for all of the ten-person groups in his department.43 Like Red Gang lodges, the Anyuan workers’ club had its own clandestine code phrases. Although the public motto was sufficiently innocuous to win the instant support of the magistrate, the internal maxim—which new members pledged to keep confidential—was more revealing of the proto–labor union’s actual aspirations: “protect workers’ interests and relieve the oppression and suffering of the workers.” As was true for secret societies, membership demanded an entrance fee. New initiates, after swearing a solemn oath of unity and a pledge of mutual aid, were required to contribute the equivalent of one day’s wages. Thereafter, a modest monthly fee was charged to underwrite basic operating expenses.44 Even so, finances remained an issue, and for the initial six months of its existence nearly half the income of the workers’ club (90 yuan out of a total revenue of 206 yuan) came in the form of a loan from Li Lisan himself.45

The reliance on recognizable secret-society conventions to build new revolutionary organizations was not unique to Li Lisan and the fledgling Anyuan workers’ club. At this same time, peasant movement activist Peng Pai borrowed liberally from Triad traditions to establish a radical peasant union in his native county of Haifeng, Guangdong. As Fernando Galbiati writes of the former Triads who flocked to Peng’s new peasant union, “they saw no contradiction between the two.”46

|

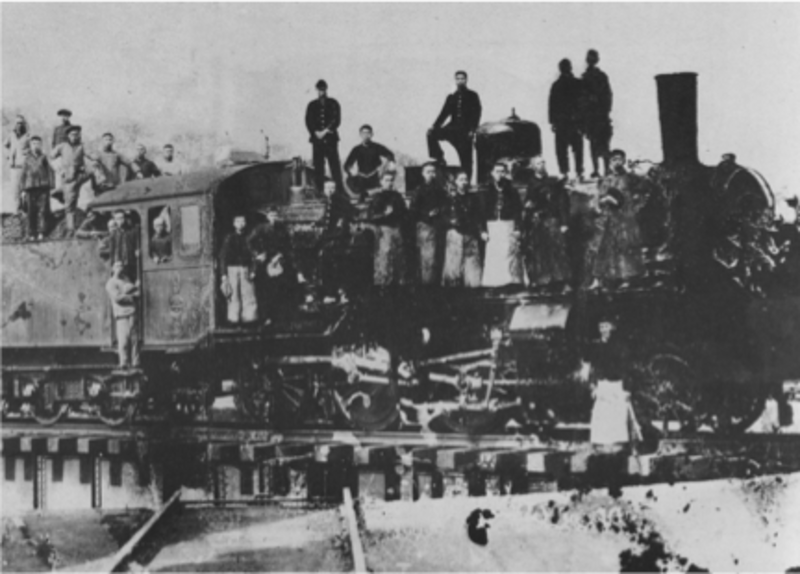

Figure 3. The Anyuan Workers’ Club Preparatory Committee. Li Lisan stands in the central row from the engine head, fifth from the right. Zhu Shaolian is looking out the window of the engineer’s booth. |

Secret societies were not the only local institution whose practices the Communists found serviceable in the process of constructing new associations. Li Lisan’s efforts at cultural positioning drew upon a broad range of familiar rituals. For example, to stir up greater interest in the workers’ club, Li decided that the night school should host a lion dance at the time of the annual Lantern Festival. In this region of China, the Lantern Festival was customarily an occasion when the local elite spon- sored exhibitions by martial arts masters, who displayed their skills and thereby attracted new disciples in the course of performing spirited lion dances. One of Li’s new recruits to the workers’ club, a highly adept performer by the name of You Congnai, was persuaded to take the lead. You was a low-level chieftain in the Red Gang whose martial arts skills were second to none. He dutifully donned a resplendent lion’s costume, tailor- made for this occasion by local artisans, and—to the loud accompaniment of cymbals and firecrackers—gamely pranced from the coal mine to the railway station, stopping along the way at the general headquarters of the company, the chamber of commerce, St. James Episcopal Church, the Hunan and Hubei native-place associations, and the homes of the gang chieftains to pay his respects. As intended, the performance attracted a large and appreciative crowd, which followed the sprightly dancer back to the workers’ club to learn how to enlist as his disciples. Contrary to popular expectation, however, the martial arts master announced to the assembled audience, “Teacher Li of the night school has instructed us that, starting tonight, we should no longer study martial arts. Instead, we should all study diligently at the night school. Anyone interested in studying, come with us.”47

It soon became clear that the Communists had in mind something altogether different from traditional pedagogy—whether of the Confu- cian literary (wen) or the martial arts (wu) variety. As lion dancer You Congnai put it to the throngs of would-be disciples, “Our teacher’s home is in Liling [Li Lisan’s native county, just across the provincial border in Hunan], but the ancestral founder of our school lives far, far away. To find him one must cross the seven seas. He’s now more than a hundred years old and his name is Teacher Ma [Marx], a bearded grandpa.”48

Li Lisan’s imaginative recruitment drive resulted in a large influx of new members to the workers’ club, but the festivities did not end there. On May Day in 1922 the Anyuan Railway and Mining Workers’ Club was publicly inaugurated with a gala parade in which hundreds of work- ers carrying red flags marched behind Li Lisan shouting revolutionary slogans: “Workers of the World, Unite!” “Long Live Labor!” “Long Live the Club!” “Down with Warlords!” “Long Live the Communist Party!” Once again Li Lisan’s ingenuity in reworking traditional practices for new mobilizing purposes was on brilliant display. Martial arts adepts among the crowd carried an open palanquin of the sort that was normally used to transport statues of deities during religious festivals (see chapter 1), but the honored passenger this day was none other than a bust of that “bearded grandpa” from across the seven seas, Karl Marx.49 Li Lisan’s innovative cultural positioning was converting familiar folk rituals into vehicles for revolutionary recruitment.

A few weeks after this boisterous public celebration of the new workers’ club, Mao Zedong returned to Anyuan to evaluate the progress of the labor movement. Expressing overall satisfaction with recent develop- ments, Mao nevertheless bluntly criticized the inclusion of “Long Live the Communist Party” among the slogans shouted in the inaugural parade. At a meeting of the recently established Communist party cell, Mao stressed the importance of strict secrecy in party affairs and the need for strengthening the organizational foundation of the labor movement before making such public declarations about the role of the Communist Party. Mao reiterated his earlier directive that mobilization must proceed gradually, avoiding any unnecessary and premature radicalism.50

Mao Zedong’s stern admonition to the Anyuan activists was an early harbinger of the Chinese Communist Party’s unease about Li Lisan’s freewheeling approach to mass mobilization. Contemporary CCP leader Zhang Guotao would later write of Li Lisan, “Completely a man of action, he looked only for results, and he was unaccustomed to restrictions from the organization . . . he always insisted that he ‘had to have an immediate solution.’”51

Impetuous and uninhibited in both personality and work style, Li Lisan’s flamboyant manner was as captivating to ordinary workers as it was disturbing to his party superiors. Li sashayed ostentatiously around the grimy coal mining town of Anyuan, dressed either in long Mandarin gown or in stylish Western coat and tie, in a fashion designed to attract attention. When the shiny metal badge (acquired in France) that he sported on his chest generated persistent rumors of Li Lisan’s invul- nerability to swords and bullets, he did nothing to dispel them. On the contrary, taking a cue from Elder Brother dragon heads whose authority rested upon their reputation for supernatural powers, Li Lisan actively encouraged the belief that he enjoyed the magical protection of “five for- eign countries” bestowed during his travels abroad.52 In this overwhelmingly male environment, where female companionship was in short sup- ply, even Li Lisan’s reputation for womanizing may have contributed to his charismatic aura.53 But surely what most endeared Li Lisan to the workers of Anyuan was the tireless dedication that he devoted to their cause, whether as a schoolteacher or as a union organizer.

Although the hundreds who had joined Li Lisan’s workers’ club still comprised but a small percentage of the total Anyuan workforce, which stood at over thirteen thousand, their enthusiasm and organization were seen by the mining company as a serious and growing threat. One of the more worrisome initiatives of the workers’ club from the perspective of the company was the establishment of a consumers’ cooperative. In July 1922 the club opened a cooperative store that offered its members low-interest loans, attractive rates for converting silver to copper currency, and basic necessities (oil, salt, cloth, rice, and the like) at below-market prices. Starting with only thirty or so members and a mere one hundred yuan in capital, the new co-op was initially a small-scale operation that conducted its activities out of the workers’ school. Modest as this begin- ning was, however, the company recognized that the cooperative—whose first general manager was Li Lisan—presented a challenge to its own monopolistic control over the workers’ livelihood. Li publicized the new venture with a simple yet appealing slogan: “cheap goods for sale.” The concrete economic benefits that resulted from co-op membership, which was restricted to those who had already joined the workers’ club, attracted a surge of new club members.54

An additional concern for the mining company was that the workers’ club (like the Red Gang whose structure it resembled) had organized its own militia. Called a “patrol team” (jianchadui), the force was recruited primarily from among Red Gang members known for their martial arts skills. Responsible for providing security for the workers’ club and its Communist leadership and for gathering intelligence on company management, the patrols carried wooden staves and drilled regularly at the night school. Their captain, Zhou Huaide, was a notoriously combative miner who hailed from Mao’s native county of Xiangtan in Hunan and had been active in the Elder Brothers Society for nearly two decades before his association with the Communists. Zhou was a veteran of the Ping-Liu-Li Uprising, having served as a petty chieftain in the Hong-jiang hui in 1906. Zhou also had a history of directing his pugilistic skills against the foreign staff at the mine, spearheading a series of assaults on German advisors and engineers until their departure en masse in 1919. Thanks to his martial prowess, Zhou was often called upon to settle disputes among his fellow workers. Because of his truculence and his standing among the workers, Zhou—like fellow gang members You Congnai (the lion dancer) and Xie Huaide (who became vice-captain of the patrols)—was specifically targeted by Li Lisan for recruitment, first to the night school and eventually to the Communist Party.55 A similar pat- tern obtained in the case of Yuan Pin’gao, a young miner from Li Lisan’s native place of Liling who was also known for exceptional martial arts skills. Yuan was persuaded by Li to study at the workers’ night school, then to join the workers’ club, then the Socialist Youth League, and eventually the Communist Party. He became a key member of the patrol team and later served as Liu Shaoqi’s trusted bodyguard after Liu’s arrival at Anyuan.56

Once prospective members had been identified and recruited, initia- tion into the Communist Party was a fairly simple affair. An inductee recalled,

Li Lisan operated a school for workers. I studied at that school. I entered the party before the strike, introduced by Li Lisan. I was inducted together with Yi Shaoqin, a supervisor on the railway. The oath swearing took place in a rented upstairs room on the walls of which there were pictures of Marx, Engels, Rosa Luxemburg, and Karl Liebknecht. The words of the oath were “Sacrifice the individual for the interests of the masses, strictly maintain secrecy, say nothing to fathers, mothers, wives, or children, observe discipline, struggle to the end for revolution!”57

For many of Li Lisan’s recruits, previous experience with Red Gang induction rituals must have lent the party initiation process a certain air of déjà vu. The qualifications for party membership were in fact quite similar to those for gang membership. When joining the Communist Party, Anyuan workers were not expected to demonstrate any particu- lar knowledge of or commitment to Marxist theory. Instead, as one of them later reported when asked about the criteria for membership, “the requirements were to keep secrets, promote mass interests, and sacrifice oneself.”58

Even if party membership did not mark a qualitative ideational break with previous secret-society beliefs and practices, rumors of the party’s rapid growth raised the disturbing specter of a militant proletariat in the eyes of the Pingxiang Mining Company. As had been the case during the Ping-Liu-Li Uprising fifteen years earlier, the challenge presented by restive workers generated a rift within the upper managerial ranks of the coal mine. Faced with the prospect of an increasingly organized and unruly workforce at just the time that a massive strike wave was sweep- ing much of industrial China,59 the directors of the mining company disagreed on how to respond. Whereas Director Li Shouquan’s revolu- tionary sympathies (see chapter 1) inclined him toward compromise, Deputy Director Shu Xiutai was intransigent. The result was vacillation between clumsy attempts to buy out the workers’ club leadership fol- lowed by hollow threats of repression. When these efforts failed to entice or intimidate either Li Lisan or Zhu Shaolian, the company petitioned the county magistrate and the garrison commander for military assistance to forcibly close down the workers’ club.60

The Great Strike of 1922

At this critical juncture, Mao Zedong paid another visit to Anyuan. Noting the further progress that Li Lisan had made in educating and mobilizing railway workers and miners alike, including the organization of a Communist Party cell that now had more than thirty members and was firmly in charge of the rapidly growing workers’ club, Mao concluded that conditions at Anyuan were ripe for a major strike. The fact that the Pingxiang Railway and Mining Company (responding to the drop in the price of coal) was several months in arrears on wage payments had angered the entire workforce. Moreover, its bungled efforts to suppress the workers’ club presented a perfect provocation for a walkout. After returning to Changsha, Mao summed up his recommendations in a letter to Li Lisan, who happened to be home in Liling at the time, calling on him to return to Anyuan immediately to carry out an orderly strike designed to elicit widespread public sympathy. Drawing on an idea from the legendary Daoist thinker Laozi that “an army burning with righteous indignation will surely win” (aibing bisheng), Mao proposed as the guiding philosophy behind the strike a literary phrase of his own: “Move the people through righteous indignation” (ai er dongren).61

In keeping with Mao’s instructions, Li Lisan hurried back to Anyuan to mobilize his followers for a general walkout. At the same time, he emphasized the important participants remembered, “Two days before the strike started, I was called to a meeting at the workers’ club at which Li Lisan presided. It was held at night, and over one hundred people attended. We were all students at the night school. Li explained that we were all going on strike, except for the electricity room, the boiler room, and the ventilation room.”62 The boiler and ventilation rooms remaining open would ensure that the pumps and fans designed to prevent flooding and gas explosions in the mine pits would continue to operate. The electricity room, which provided illumination and running water to the entire town of Anyuan, would also stay open in order to avoid plunging the community into darkness and inciting public anger and disorder.63 That these critical workshops were staffed by technicians from Jiangnan and Guangdong—the segment of the workforce among which the Hunan-born Communists had made the fewest inroads—was perhaps also a consideration in exempting them from the strike action. In any event, aside from a skeleton crew to main- tain the basic infrastructure, the whole workforce of over ten thousand miners and railway men was expected to participate.

Worried about maintaining order in this place renowned for its history of violence, Mao Zedong decided at the eleventh hour to dispatch another comrade from Hunan, Liu Shaoqi, to provide supervision and impose restraint during the impending strike.64 Liu had attended the same school as Mao in Changsha before going to the Soviet Union to study at the University of the Toilers of the East in 1921. Just returned from his year in Moscow, Liu was already known for a disciplined Leninist work style that

Mao believed could serve to temper Li Lisan’s more impulsive inclinations.65 Together, Li and Liu worked to ensure that the impending strike would proceed under party command. A miner involved in the preparations explained,

The night before the strike got underway, the leaders and members of the workers’ club convened a meeting that lasted the entire night to decide upon the strike resolution and to figure out various strike- related measures. At that time management regarded the club as a pain in the neck and the immensely popular Li Lisan as a thorn in the flesh. So they threatened to harm him. At the meeting, everyone agreed that Li Lisan should not go out in public for the period of the strike. But then who should be in charge of the negotiations? This led to a very spirited debate. . . . In the end, Comrade Li Lisan made the decision, “The strike is led by the party. Comrade Liu Shaoqi was sent by the party to undertake a leadership role. Naturally he must serve as the negotiator.” Finally, the meeting decided that Li Lisan would serve as supreme commander of the strike while Liu Shaoqi would serve as top negotiator. Next on the agenda were the strike demands to be negotiated. This issue also generated considerable disagree- ment. Some workers raised unrealistic demands. Only after patient persuasion and explanation by Li Lisan and Liu Shaoqi did these workers agree to drop their radical demands.66

Under the combined leadership of Li Lisan and Liu Shaoqi, the Anyuan strikers presented the railway and mining company with a set of demands that they considered ambitious yet attainable: payment of back wages, improvement in working conditions, reform of the labor contract sys- tem, and—most important of all from the perspective of the Communist leaders—a guarantee of recognition and financial support for their newly established workers’ club.

In the spirit of Mao’s classical admonition to move the people through righteous indignation, Li Lisan came up with a stirring colloquial slogan for the strike: “Once beasts of burden, now we will be men!” (congqian shi niuma, xianzai yao zuoren). Referring to unskilled laborers as “beasts of burden” (niuma) was a familiar trope, but the call for these “cattle and horses” to stand up as men was fresh and arresting.67 This cri de coeur was elaborated in a strike manifesto (also composed by Li Lisan) intended to elicit widespread public sympathy for the workers’ cause.68 In the centuries-old tradition of protest petitions,69 the manifesto emphasized the desperate defensive motivations of the participants. Significantly, the argument was framed not in terms of class struggle but as a plea for human dignity:

Our work is so difficult; our pay so meager. We are often beaten and cursed, robbing us of our humanity. The oppression we suffer has already reached the extreme limit so we are seeking “better treat- ment,” “higher wages,” and an “organized association—a club.” . . . We want to live! We want to eat! We are hungry. Our lives are in danger. In the midst of death we seek life. Forced to the breaking point, we have no choice but to go on strike as our last resort. . . . Our demands are extremely reasonable. We are willing to give our lives to reach our goals . . . Everyone, strictly maintain order! Carry through to the end!70

As the manifesto implied, public support depended upon the ability of the strikers to ensure order. With some five thousand unemployed laborers milling about the town of Anyuan at the time, the possibility of violent confrontations between strikers and strikebreakers was of particular concern.

Both Li Lisan and Liu Shaoqi, like Mao before them, recognized that the key to maintaining order was the cooperation of the Red Gang. Accordingly, they agreed that Li Lisan—accompanied by workers’ club patrolmen and gang members Zhou Huaide and You Congnai—should visit the local dragon head to secure his assistance. Bearing a bottle of liquor and a rooster, the basic elements of a Triad-type initiation rite, Li and his companions went to the society lodge on a night when they knew that the top leaders of the Red Gang had been planning to hold an induction ceremony. Li strode brazenly into the main hall, plunked his gifts on the altar, and—using Elder Brother code language that his associates had taught him—indicated his desire to enter the fraternity. When the Red Gang leaders expressed some doubts about Li Lisan’s sincerity, Zhou Huaide rushed to his defense: “I won’t deceive my brothers. Mr. Li has traveled all over China, to cities large and small. He has also gone over- seas to many countries. He has taken ‘Ma the Bearded’ [Marx] and ‘En the Bearded’ [Engels] as his teachers, and his person is protected by these two foreign worthies.” You Congnai added, “Whoever makes friends with Mr. Li enjoys good fortune.” Persuaded by this character reference from his underlings, the dragon head accepted Li Lisan’s presents and invited him to state his concerns.71 Li made three requests—the suspension of gambling operations, opium dens, and looting incidents for the duration of the strike. When the Red Gang leader beat his breast three times to indicate his assurance that all three demands would be met, the strike was called.

Li Lisan later acknowledged the signal importance of this diplomatic mission to the Red Gang in facilitating the success of the Anyuan strike, explaining how he had won the dragon head’s acquiescence by framing his request in a manner congruent with secret-society precepts:

We paid a great deal of attention to working with the Red Gang. Many of the workers had joined the Red Gang, and the Red Gang leader was an advisor to the mining company. The great majority of labor contractors were his followers, and the capitalists at the mine relied on them to oppress the workers. They used concepts such as “honor,” “protecting the poor,” “seeking happiness for the poor,” and so on to trick the workers. Thanks to our efforts, several of the lower-level Red Gang chieftains joined the party. Before the strike, our biggest fear was that the Red Gang would break the strike. So Liu Shaoqi instructed me to have a couple of gang chieftains under our influence take me to see the Red Gang leader. I bought some presents and went there. The head of the Red Gang was very pleased that I had come. He called me Director Li (as workers’ club director), and after we had drunk the rooster blood (I had brought along a rooster), I told him we were planning to go on strike. I also explained that the strike was intended to help our impoverished brothers “seek happiness,” “protect the poor,” and so forth. I asked that he do the “honorable” thing by helping out. He slapped his chest and said, “I will definitely help.” I immediately raised three demands for the period of the strike: 1) close the opium dens, 2) suspend street gambling, 3) prevent looting. He slapped his chest three times in a row: “The first point, I guarantee, the second point I guarantee, and the third point I also guarantee.” He even wrote the first and second points into a public notice. The implementation of these three provisions had a dramatic effect on [Anyuan] society. Even some capitalists and intellectuals thought the workers’ club was pretty amazing (because for so many years these problems could not be solved, but the strike completely resolved them).72

Having secured this critical guarantee of Red Gang cooperation, the strike commenced at two o’clock in the morning on September 14, 1922, among the most reliable base of Communist support, the railway workers. Within two hours, however, the walkout had spread—by careful prearrangement—to the rest of the workforce. At each of the more than forty workstations, yellow triangular flags—bearing the characters for “strike”—were unfurled and patrols were stationed to ensure that no one entered the premises. Workers were told to return to their homes or dormitories to reduce the potential for public disorder.73 Notices were posted on the streets, in all the residential districts, in the workers’ dormitories, at the train station, and at the entrances to the pits urging full cooperation: “Wait for an announcement from the club before resuming work!” “Everyone return home!” “No disorderly conduct!”74

With virtually the entire workforce idled, a group of labor contractors—fearing an end to their lucrative livelihood should the strikers win their demands—attempted to intervene. The general foreman, Bearded Wang the Third (see chapter 1), led this opposition. As Liu Shaoqi and Zhu Shaolian described Wang’s unsuccessful effort,

The labor contractors were deeply upset by the strike. They tried by every means possible to destroy it in order to protect themselves. The worst offender was General Foreman Wang Hongqing (from Hubei), who received thousands of yuan each month from the sale of labor contractor positions. After the strike began, Wang convened a meeting of all the labor contractors for underground operations to discuss methods for breaking the strike. They decided that every contractor would offer some of the workers under his control full pay simply for entering the pits without doing any work. Some of the workers, either because of family pressure or greed, wanted to take advantage of this invitation. But the workers’ patrols were very strict and did not allow them to enter the pits.75

To carry out its enlarged responsibility for combating scabs, the patrol team of the workers’ club was expanded in both size and scope. In addition to guarding against strikebreakers, a major duty of the patrols was to conduct nightly inspections of the workers’ dormitories to ensure that the idled workers remained indoors and refrained from gambling or other activities deemed corrosive of strike discipline. For the duration of the strike, by eight or nine o’clock at night the normally bustling streets of Anyuan were entirely empty except for the workers’ patrols. Wearing red armbands, waving white flags, and armed with wooden staves and metal bars, the patrols also provided protection—and the threat of an iron fist—for Liu Shaoqi and Li Lisan during their negotiating sessions with the railway and mining company management. When word of an assas- sination plot aimed at Li Lisan reached the strikers (via Li’s fellow Liling native, mine construction foreman Chen Shengfang), a special contin- gent of pickets was deployed as round-the-clock bodyguards. On more than one occasion, threats from the workers’ club patrols to destroy com- pany property if management were to reject the strike demands served to expedite the negotiation process.76

Despite the social tensions that the work stoppage inevitably generated, the strikers continued to stress the defensive motivations that underpinned their struggle. Halfway into the strike, the Anyuan workers’ club, with Li Lisan’s guidance, issued a second manifesto, addressed to “fathers and brothers in all social circles”: “The life we have lived in the past is not the life of a human being; it is the life of a beast of burden or a slave. Working for a dozen hours a day, day after day in the depths of darkness, we suffer beatings and curses. We definitely do not want to continue this nonhuman sort of life. . . . Fathers and brothers! Twenty thousand of us workers are on the verge of death! Can you bear to watch death without offering assistance?”77 The consistent demand for human dignity, presented as a plea for sympathy from fellow kinsmen, ultimately proved persuasive. After five days off the job, with no injuries or major property damage, the strikers won agreement to nearly all of their demands. This impressive outcome, at a time when the labor movement was being suppressed in other parts of China, contributed to the iconic status of the Anyuan strike in the annals of the Chinese Communist revolution. CCP labor organizer Deng Zhongxia wrote of Anyuan in his influential history of the Chinese labor movement, “The strike demon- strated the great enthusiasm and courage of the masses. After five days, the company caved in and accepted the workers’ thirteen demands, the most important of which were the recognition of the authority of the workers’ club to represent the workers and a wage increase. It was a complete victory.”78 Even a labor historian hostile to the Communist cause acknowledged the strike’s importance: “The most notorious strike in the annals of the Chinese labor movement was the strike in the Anyuang [Anyuan] and Chuping [Zhuping] Railroad in September, involving an overwhelming body of 20,000 miners and 1,500 railway workers. . . . [T]he workers in Anyuang and Chuping started to organize themselves and built a clubhouse which was only another name for a union.”79

Historians and activists alike attributed the Anyuan victory to the power of a united, militant workforce. But leadership was also a critical factor. As Mao Zedong had calculated, Li Lisan’s penchant for creativity and Liu Shaoqi’s tempering concern for control were a winning combina- tion. Because of the threat of assassination, Li Lisan was forced to spend part of the strike period in hiding and to cede much of the day-to-day responsibility for negotiating to Liu Shaoqi. Li Lisan remained secretary of the Anyuan party committee as well as director of the workers’ club, however, and it was he who crafted the strike manifestos, signed the final agreement on behalf of the workers, and presided over the jubilant victory celebration at the conclusion of the strike action.80 Li’s cultural positioning—a blend of old and new that augmented prevailing notions of invulnerability and master-disciple relations, for example, with novel claims to overseas sources of power—contributed to a leadership style that was both appealing and effective. Liu’s obsession with order was also instrumental in forestalling violence and winning widespread public support for the walkout.

|

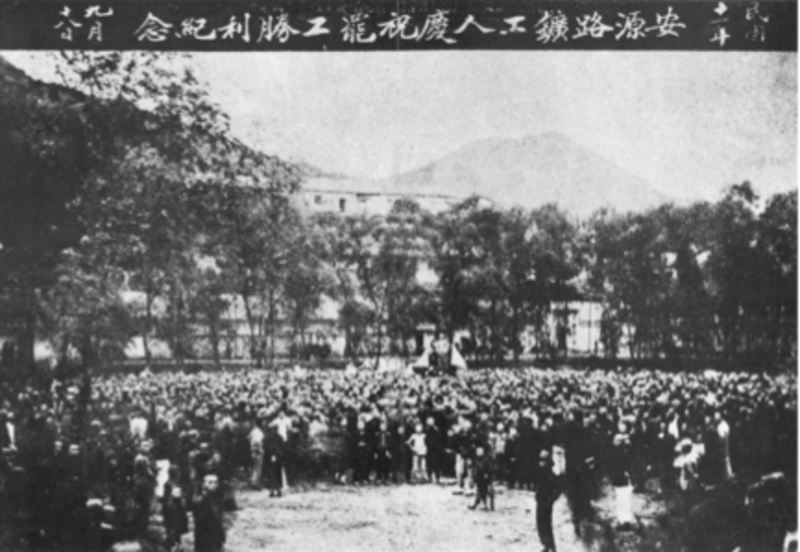

Figure 4. Celebrating the victory of the Anyuan Great Strike on September 18, 1922. |

As soon as the strike settlement was signed in the chamber of com- merce offices, Li Lisan convened a massive outdoor celebration in the open field in the center of town. To thunderous applause, Li ascended a makeshift stage. When he began to speak, a hush fell over the assembled multitude, who hung on his every word: “The victory of this strike was entirely due to our singleness of purpose. I hope everyone will forever maintain this spirit.”81 Li concluded his remarks with a rousing cheer— “Once beasts of burden, now we will be men!”—a mantra that the crowd echoed with a deafening roar.82 A jubilant march through the streets of Anyuan to the accompaniment of firecrackers was followed by the prom- ulgation of a triumphant work resumption manifesto, drafted by Li Lisan: “The strike has been victorious! . . . In the past, workers were ‘beasts of burden’ but now it’s ‘Long Live the Workers!’ . . . We have received the support of the garrison commander and the martial law command post as well as negotiators from among the gentry, merchant, and educational circles, allowing our demands to be entirely satisfied. We thank them profoundly. . . . This strike was the first time that the workers of Anyuan lifted up their heads, exposing the dark side of Anyuan. From today for- ward we are closely united, of one mind, in the struggle for our own rights. We now wish to declare ‘Long Live the Workers!’ ‘Long Live the Workers’ Club!’”83

More prosaically, in keeping with his controlled Leninist approach, Liu Shaoqi summed up the achievements of the strike this way: “The Great Strike lasted, altogether, five days. Discipline was extremely good and organization was very strict. The workers did a fine job of obeying orders. It cost the workers’ club only a total of some 120 yuan in expenses; not a single person was injured and no property was damaged. Yet a complete victory was won. This truly was a unique event in the experience of the young Chinese labor movement.”84

Elite Involvement

The Anyuan strike is portrayed in CCP legend as a shining example of pure proletarian prowess. The actual story was considerably more complicated. Intellectuals, local gentry, military officers, merchants, Red Gang dragon heads, and church clergy also contributed to its success. As we have seen, the strike of 1922 was launched and led by outside intel- lectuals; moreover, its nonviolent, swift, and generous settlement was enabled only by the sympathetic involvement of a wide array of local elites. At this stage in the Chinese revolution, Li Lisan would later recall, it was still possible to elicit the gentry’s cooperation by a policy of “education for national salvation.”85 The ready acquiescence of the Pingxiang County magistrate to Li’s pedagogical proposal had indeed set the stage for the entire mobilization effort. When the strike erupted, moreover, the head of the most powerful lineage in Pingxiang, Wen Zhongbo, was vocal in pressing for a swift settlement that would meet most of the workers’ demands.86 Wen’s position was quite possibly a product of the longstanding resentment of the modern mining company on the part of the local gentry, but elite involvement was not limited to the gentry. Even “capitalists” seemed willing to betray their class status. As Li Lisan acknowledged, “The family members of mine director Li [Shouquan] all joined the workers’ club at the time of the strike.”87

A powerful element of the local elite whose sympathetic stance facili- tated the peaceful resolution of the strike was the military. At the outset of the strike the mining company had persuaded the garrison commander of western Jiangxi, who received a generous monthly stipend from the mine, to declare martial law in Anyuan. However, the officer in charge of the martial law command post, Li Hongcheng, was so impressed by the effectiveness of the workers’ club patrols—whose discipline was noticeably superior to that of his own motley crew of soldiers—that he ordered his troops not to interfere with the strike. The soldiers, having heard the pervasive rumors of Li Lisan’s magical invulnerability, were happy to comply.88 Liu Shaoqi expressed appreciation for the military’s accom- modation: “Brigadier Li understood that the workers were demanding an improvement in their livelihood, which could not be settled by military force. Over time he even became an active advocate of the strike, making a huge contribution.”89

When the workers’ club delivered its list of strike demands to the company management (with copies sent to the county magistrate as well as the garrison command), an addendum was attached: “If you wish to negotiate, please send formal representatives designated by the cham- ber of commerce to meet with Liu Shaoqi.”90 Initially, the company was represented in the strike negotiations by its newly appointed deputy director, Shu Xiutai, who hoped that his unbending stance would so ingratiate himself with the upper echelons of the Hanyeping Coal and Iron Company that he might be tapped to succeed Director Li Shouquan. But, after repeated importuning from the chamber of commerce and local gentry, Director Li himself helped broker a peaceful resolution.91

The head of the Anyuan chamber of commerce, Xie Lanfang (the same friend of Li Lisan’s father who had delivered Li’s initial petition to the county magistrate), played a major role in convincing the railway and mining company to accede to the strikers’ demands.92 Li Lisan explained, “The negotiations . . . were mediated by the chamber of commerce. . . . We had good relations with the chamber of commerce. I used a friend of my father’s named Xie.”93 Xie Lanfang was hardly a disinterested arbiter; Anyuan workers and their families were the main customers for his many grocery stores dotted across western Jiangxi, and the business- man no doubt appreciated that a hike in workers’ wages would bring him increased sales. In serving as intermediary between strikers and management, Xie was joined by craftsman, landlord, and capitalist Chen Shengfang, from Li Lisan’s native county of Liling, who enjoyed close relations with the strike commander as well as with company management. At a crucial juncture, Chen Shengfang, who was hosting the negotiations at his Anyuan home, expedited the process by warning mine director Li Shouquan that unless the company were willing to accept the strikers’ demands, Li Lisan would feel compelled to give in to the workers’ desire for a violent resolution.94 Even the rector of the St. James Episcopal Church, in his role as principal of the mining company’s school, volunteered his services as mediator. Many of his parishioners were active in the strike, and the warden of his church vestry was a profes- sional photographer who, at the invitation of the workers’ club, shot the only surviving photos of the victory celebration following the strike.95

The Anyuan strike of 1922 stands as one of the major accomplishments of the early Chinese Communist Party. In less than a year’s time, Li Lisan and his comrades had managed to mobilize a remarkably successful protest among a large, unruly, and initially mostly uneducated workforce. Although Anyuan proved exceptionally amenable to revolutionary initiatives (due to a combination of its rebellious heritage, concentrated living and working conditions, Hunan connections, cooperative local elite, and above all the brilliant organizing efforts of Li Lisan), the basic model that the Communists followed at Anyuan was standard operating procedure for the day.

The recipe was copied in part from Russian revolutionary experience, but it also displayed a distinctly Chinese flavor. The Communists took special advantage of the cultural capital that Confucianism bestowed upon educators to “teach revolution” to their worker-pupils. Sporting literati attire and spouting literary adages, cadres drew from a deep reservoir of both elite and popular respect for intellectuals to pioneer a highly successful nonviolent movement. Martial arts traditions and underworld Triad connections were crucial to the mobilization effort, but these “heterodox” ties were subsumed within a broader “orthodox” pedagogical strategy. Li Lisan’s masterful mix of literary and military—wen and wu—authority was a winning combination that established his own leadership credentials within the all-male community of miners and railway workers while at the same time garnering support from a wide spectrum of the local elite.

Framing the strike as a plea for fundamental human dignity was a masterstroke conceived by Mao Zedong (who presented it in literary lan- guage) and executed by Li Lisan (who translated the concept colloquially into a stirring slogan that promised to make “men” out of former “beasts of burden”). As John Fitzgerald argues in his study of Chinese nationalism, a demand for dignity has been at the heart of twentieth-century Chinese political discourse, fueling the outrage that has erupted repeatedly in protests against international humiliation.96 Similarly, Steve Smith’s study of the Shanghai labor movement locates the nexus between working-class protest and nationalism in a new stress on human dignity that nevertheless echoed much older values: “The discursive link between national and [working-] class identities was forged, above all, around the issue of humane treatment. Workers’ refusal to be treated ‘like cattle and horses’ derived from a new but powerfully felt sense of dignity, albeit one that resonated with traditional notions of ‘face.’”97 Presenting strike demands as a defensive cry for human dignity was a unifying strategy as reassuring to the local elite as it was appealing to aggrieved coal miners. The concerted efforts of various local power holders were critical to the swift and smooth resolution of the conflict.98

Mao’s periodic interventions were vitally important, but they were fully in line with official party policy. Workers’ schools, elite alliances, secret-society cooptation, and orderly strikes enforced by worker patrols were staple ingredients in CCP-sponsored labor agitation around the country during this period. In recognizing that the mobilization of the Anyuan workers required the complicity of power holders who had long wielded effective cultural control over the labor force, Mao and his comrades avoided the dismal failure that so frequently greets attempts by outside radicals to organize among coal miners. In the case of America’s Appalachian Valley, for example, repeated efforts by committed activ- ists to unionize the miners were frustrated by the powers that be. As John Gaventa explains, “Those who sought to alter the oppression of the miner—the northern liberal and the Marxist radical—failed partly because they did not understand fully the power situation they sought to change. . . . The radical sought to develop a revolutionary class con- sciousness, but he misunderstood the prior role of power in shaping the consciousness which he encountered. It was the local mountain elite, who knew best the uses of power for control within their culture, who effectively capitalized on the mistakes of the others.”99 The case of Anyuan presents a dramatic contrast to this familiar scenario. As cul- tural insiders, Mao Zedong, Li Lisan, and Liu Shaoqi were keenly aware of the need to engage and thereby neutralize the control of local power holders. Working within the existing power structure, and using familiar symbolic tropes to gain widespread support, the young Communists succeeded in mobilizing a spectacularly successful strike that opened the door to a new industrial order at Anyuan.

By all accounts, the Great Strike of 1922 resulted in notable gains for the workers of Anyuan. One participant remembered,

The victory of the strike greatly boosted the workers’ confidence. My strongest memory is of the huge differences before and after the strike. The workers’ livelihood improved markedly and the orga- nizational work of the club was much expanded. Unlike before, the foremen and staff were no longer arrogant and didn’t dare to beat or curse the workers at will. The workers gained some political rights and some economic rights. There was a general wage hike. Before the strike, my monthly wage was three dollars. After the strike, it was immediately increased to four and a half dollars. The food in the min- ers’ cafeteria improved; we were no longer served moldy red rice and withered vegetables.100

The perceptible improvement in material conditions fostered a more self- assured mentality on the part of many workers, who themselves became active participants in creating a new revolutionary culture.