Political paralysis has set in following the advent of the Fukuda government in September 2007, and is likely to prevail so long as the contradictory results of the two recent elections— the overwhelming victories for the ruling Liberal-Democratic Party (LDP) in 2005 and for the opposition Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) in 2007—are not resolved.

Here two prominent Japanese political scientists assess the results of a national survey designed to clarify the public mood and distinguish the views of supporters of the dominant LDP and DPJ. On the basis of their findings they draw lines of principle and policy around which a more coherent two party system might develop in future, hopefully resolving the current stalemate. (GMcC)

Introduction

Immediately after the Upper House elections in summer 2007, debate between the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) and the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) was expected to intensify as both parties made their bids for power in the general election playoff. However, while the extraordinary Diet session, which began in the fall of 2007 was certainly protracted, the sole focus was both parties’ manuvring over the new Anti-Terrorism Special Measures Law, with no rigorous debate in evidence.

This betrayal of public expectations as to how politics should have played out is the result of the DPJ’s lack of both political strategy and political vision. The still-lingering talk of a “grand coalition” is one manifestation of this. The focus here is not on political strategies designed to drive the incumbent ruling parties into dissolving the Diet. Rather, we want to examine the political vision that the parties bring to their bids for power—what kind of Japan they seek to create—which is a far more critical issue at this juncture than the power struggle aspect.

Japan has found itself with a divided Diet due to the coexistence in the body of two completely different tides of popular will, namely the popular will of 2005 and that of 2007. In 2005, the public supported small government, and this sentiment is still reflected in the form of the LDP’s absolute majority in the Lower House. In 2007, public feeling shifted toward criticism of widening social disparities and an emphasis on a better work-life balance, creating an opposition party advantage in the Upper House. The intermingling of these two strands not only in both Houses but within the various political parties, in the media and in public opinion, is currently blurring the axis of debate.

The major premise in considering the policy issues facing the next administration must be the will of the people as manifested in last summer’s Upper House elections. The DPJ’s duty as a political party that could soon be making government decisions is to present a policy framework for realizing their slogan “People’s lives come first.” The will of the people as evinced in the Upper House elections suggests that malaise over growing social disparities and fears as to the sustainability of social security are shared to some extent across society as a whole. Moreover, as concern grows over the increasing severity of environmental destruction, one strand of public opinion is also urging replacement of the current laissez-faire approach to economic activities with public regulation of some kind.

However, neither Japan’s political parties nor the media have come up with any clear vision as to the policy menus that could be applied to resolve these issues. For example, while the DPJ has produced a more comprehensive anti-global-warming approach than the LDP—the DPJ is still calling for abolition of the temporary gas tax rate. Price falls inevitably boost gasoline demand, so the DPJ’s views on this issue are unclear. The party’s failure to provide any indication as to how it will fund its priority on lifestyle other than ‘curtailing wasteful expenditure’ also presents the DPJ as short on policy capacity.

Some of those politicians who still call themselves reformers criticize the LDP for abandoning its reform campaign on the pretext of reducing disparities. For example, speaking with Maehara Seiji, Koike Yuriko observed that the LDP under Fukuda’s leadership has abandoned the new urban backers that it acquired during the Koizumi era, and is instead trying to use pork barrel to regain its former rural support. Maehara is similarly dissatisfied with the DPJ’s emphasis on lifestyle (Asahi Shimbun January 7, 2008).

There is also serious media confusion. The media have rung alarm bells over the “working poor” and the collapse of medical care, and are calling for strong measures. However, when the government attempts to put money into these very causes, it faces a storm of media criticism. For example, at the end of last year when the Ministry of Finance produced a preliminary budget proposal, newspaper editorials and columns slammed it as a return to pork-barrel politics induced by pressure from ruling party politicians, or as a reform rollback.

The purpose of policy is to alter distribution. Deregulating the labor market to open the way for low-wage labor redistributes wealth from workers to companies. Those who have benefited from Japan’s buoyant economy have also benefited from these policies. Redistribution favoring the strong has been lauded as reform. By contrast, recipients of rural subsidies and other measures aimed at reducing social disparities are the weak: farmers, shop-owners and the like. Redistribution to these weak members of society is being criticized as pork-barrelling. The media evinces a decided contradiction in bemoaning the distortions created by neoliberalism while still retaining a neoliberal belief in small government that channels into support for the spending curbs put forward by the Council on Economic and Fiscal Policy.

In the political world, growing concern over social suffering seems to be paralleled by criticism of and hesitation over the use of public money in policy implementation. This criticism arises from memories of how various types of policy expenditure were linked to vested rights and corruption. However, one thing should be clearly understood. Those commentators currently calling for something to be done about social disparities and social security are not seeking the answer in old-fashioned economic measures. They see the government as neglecting its essential obligations in the name of reform, and want those obligations to be taken back on board. It is the government’s duty to provide universal public services such as medical care and education. However, these services have been eroding due to medical care and local allocation tax reforms. The problem is that the steep rise in informal employment has created an excess of low-wage labor, making it difficult to preserve human dignity, but the government has done nothing to redress these new circumstances. Shouldering government obligations in this regard is a far cry from pandering to old clients.

Perhaps another reason that there is still no consensus over public spending is the difficulty in seeing how the policies currently proposed will serve to erase current social contradictions. To make that connection clear, rather than just creating micro policies addressing individual issues, the government needs to draw up a comprehensive social vision for the years ahead, placing individual policies within that framework.

To provide the groundwork for creating this kind of overarching image, we conducted an opinion poll on the kind of socioeconomic system people in Japan really want. There is a common misperception that policy-making ability is the ability to make the kind of small-scale decisions sought from bureaucrats. Political parties are also hesitant to enter discussion on the grounds that any vision that departs significantly from the status quo would be merely a pipe dream. However, to move beyond Japan’s current crisis, a major vision will be vital. Knowing what the people want should enable political parties and politicians, as well as academics and the media, to present such a bold vision.

1. Public perceptions of the current situation

Our survey, which used the random-digit-dial method over a sample of approximately 1,500 people around Japan, looked at the public’s policy preferences following the structural reform era. The basic drive of Koizumi Junichiro’s structural reforms was to abandon the traditional Japanese-style economic system in favor of the neoliberal American model. We sought to ascertain how people rate the results of the structural reforms, and, based on those perceptions, where public opinion stands on rejecting the Japanese model, adopting the American model, or seeking some other model entirely. A detailed analysis will be presented in the following sections, but to cut to our conclusions, we believe that the poll revealed the following trends in public perceptions.

Table 1: Party support ratings

(a) Negative evaluation of the structural reforms

When asked about the current state of Japanese society, as seen in Table 2, the vast majority of respondents gave negative responses, citing growing “disparities between rich and poor” and “slipping quality of public services,” followed by “the belief that any means of making money is justified.” Despite Japan’s experiencing its longest-ever economic expansion in the latter half of the 2000s, very few people remarked on the recovery of economic vitality, and the results of political and administrative reforms similarly received few positive evaluations. There was virtually no disparity in these trends on the basis of gender, region or occupation. One clear trend in terms of political party support was that the number of LDP supporters who lauded the achievement of economic recovery was ten percentage points higher than overall.

Table 2: What have been the consequences of the Koizumi and Abe administration reforms for Japanese society?

(b) Serious unease over future livelihood

As seen in Table 3, over 70 percent of respondents took a dim view of the future with respect to their individual livelihood, reporting that they felt anxious or somewhat anxious. Only 28 percent reported feeling secure or fairly secure. These results were virtually the same across all genders, occupations, regions and generations. From the political party angle, one conspicuous finding was that around 40 percent of LDP supporters reported feeling a sense of optimism about the future. With only 20 percent of DPJ supporters feeling optimistic while nearly 80 percent feel pessimistic, the contrast with LDP supporters was marked. We can see that people who feel that their livelihood is secure tend to support the LDP.

Table 3: Image of future lifestyle

(c)Strong demand for public services

Asked what they perceived to be the main threats to a stable life in the future, as seen in Table 4, “the collapse of the pension system” and “the collapse of medical care” took first and second place.

Table 4: Threats to future lifestyle

Although since last summer the media have focused primarily on economic deceleration and low stock prices, few respondents felt that the weakening economy posed a threat to their lifestyle, highlighting instead the collapse of social security. Put another way, this suggests major demand for social security and other public services. In addition, as seen in Table 5, when asked what elements of the traditional Japanese system should be changed, the majority of respondents—36 percent—chose “strengthening public social security.”

Table 5: Elements of the traditional Japanese system that should be improved

This indicates growing awareness of how the Japanese social security system has traditionally depended on company-based employee welfare measures and family-centred “services in kind.” Moreover, amid the collapse of the family and changing employment practices, the public seems increasingly keen to have social security established as a public institution. Table 6 shows respondents’ views on measures to address poverty. With almost half selecting “employment training and other government support for people trying to achieve economic self-sufficiency,” it would seem that in this area too, people are looking for the provision of public services rather then direct cash handouts.

Table 6: Ways of dealing with poverty

(d) Hopes for the Scandinavian welfare model

When asked to choose what kind of social models they considered desirable, as seen in Table 7, just below 60 percent of respondents chose “a society like Scandinavian countries that stress welfare,” followed by more than 30 percent who sought a return to “a society like traditional Japan that stresses lifelong employment.” Less than seven percent of respondents selected “a society like the U.S. that stresses competition and efficiency.”

Table 7: The ideal Japan of the future

In other words, in spite of the neoliberal reforms which have been introduced since Koizumi came to power, very few people support the U.S. model. In terms of political party support, support for the U.S. system was extremely weak in all cases. Support for a return to the traditional Japanese system was ten percentage points higher among LDP supporters than overall, while supporters of the DPJ, Komeito and Communist parties leaned primarily toward the welfare society model. These trends are consistent with the low evaluations of the structural reform program noted in (a).

(e) Opposition to a consumption tax hike

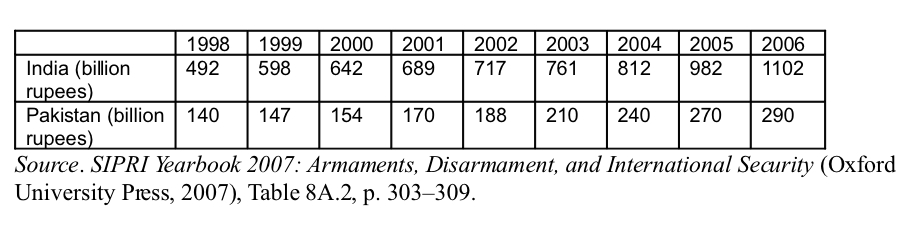

Table 8 reveals very strong opposition to the recently debated consumption tax hike as a means of funding a welfare society. Viewed in terms of political party affiliation, approval for a hike was more than ten percent higher among LDP supporters than among other parties’ supporters.

Table 8: Fiscal sources for social security

According to the results of a September 2005 poll conducted by the Cabinet Office on social security and the tax burden, two-thirds of respondents felt that an increased tax burden would be inevitable in order to maintain or improve upon the current level of social security. Combined with the results of our survey, the only possible interpretation is that the public will accept a greater tax burden where it is levied in the form of corporate tax and income tax paid by the affluent, but not in the form of a consumption tax paid by ordinary people.

(f) A fair assessment of the traditional Japanese system

In association with their overall evaluation of the traditional Japanese system, “maintaining employment,” “personal relations at the community level” and “protection of small and medium enterprises and the self-employed” came out ahead as elements of that system that should be maintained. In terms of elements that need to be improved, the top choice was the above-mentioned “strengthening public social security,” with “reducing bureaucratic power” also attracting strong support. Taken together with the views on social models noted in (d), it would seem that while the public wants to maintain the traditional Japanese virtues of harmony and equality, this feeling exists in parallel with the realistic assessment that returning to the old system is not a feasible option.

Based on this reading of the will of the people, we turn next to what political parties need to do in order to produce the kind of policy vision that the public are looking for in the next election.

2. An axis of opposition begins to emerge

(a) New welfare preferences

Survey results suggest that, following a long period of complexity and distortion, a new axis of policy opposition between the two main parties has finally begun to emerge.

Survey respondents were asked to choose the best model for Japan’s future from among the U.S. model, which emphasizes competition and efficiency, the welfare-oriented Scandinavian model and the traditional Japanese model of lifelong employment. More than 60 percent opted for a welfare emphasis, while 30 percent prioritised lifelong employment. Welfare accordingly seems to have taken on a slightly excessive potency, but what is interesting is that the number of LDP supporters looking for a Scandinavian-style welfare emphasis exceeded DPJ supporters by a hefty 10 percentage points. When it came to those elements of the traditional Japanese system that needed to be reformed, the number of LDP supporters who felt that “the principle of competition needs to be introduced and excessive equality redressed” was also more than 10 percent greater than in the case of DPJ supporters.

Among DPJ supporters, on the other hand, in addition to significant support for a Scandinavian-style welfare emphasis, the number of respondents focusing on “strengthening public social security” as the element in the traditional Japanese system that needed to be reformed was close to 10 percentage points higher than among LDP supporters. DPJ supporters also outnumbered LDP supporters by 18 percentage points in calling for “guaranteeing a minimum income” as a means of dealing with poverty.

Looking at the axis of opposition in regard to socioeconomic policy, unexpectedly clear differences in preferences appear to be emerging among LDP and DPJ supporters. Is the new axis the familiar small government/big government opposition? Are DPJ supporters simply looking for big government to institute redistribution from above? In fact, they are not. When attitudes to issues on the values/culture axis such as social accountability, government dependence, and traditional family are added to the socioeconomic policy axis, a more three-dimensional picture emerges.

In terms of points to reform in the traditional Japanese system, alongside “strengthening public social security,” many DPJ supporters chose “reducing bureaucratic power,” in fact outnumbering LDP supporters by as many as 8 percentage points in this regard. DPJ supporters were also more than 10 percentage points ahead of LDP supporters in calling for social security to be funded not by increasing the public tax burden but by some other means such as administrative reform.

Along the same value/culture axis, LDP supporters outnumbered DPJ supporters by more than 5 percentage points in selecting “traditional families in which men and women have different roles” as an element of the traditional Japanese system that should be maintained. Compared to DPJ supporters, LDP supporters also sought on the one hand deregulation and strengthening of the competition principle, and, on the other, preservation of the traditional value system. DPJ supporters were persuaded by neither of these, and were also critical of bureaucrat-led politics. This could be interpreted as a preference for individual autonomy over traditional authority.

The kind of pattern evinced by LDP supporters, whereby the market orientation along the economic axis links to conservative and traditional preferences along the values/culture axis, has also been called neoconservatism. Accordingly, few people regard the current pattern as anomalous. If the market destabilizes traditional local communities and families, the call for a return to traditional values to shore them up seems a somewhat circular approach, but at the same time it has a certain logic.

Thinking in terms of the traditional welfare state, it might seem contradictory that DPJ supporters, on the other hand, should emphasize welfare while shunning big government. This could be interpreted as confusion following the shift from an emphasis on market-oriented reforms to criticism of growing social disparities. There are also probably some analysts who view it more cynically as the vestiges of a pork-barrel election campaign whereby disparities are supposed to be redressed without increasing the public tax burden.

However, we believe that a new policy axis is peeking through here.

People were protected under the traditional Japanese system through enclosure of the individual within firms and industries that were themselves under the protection of government. Before the Koizumi reforms, the DPJ’s identity revolved around revealing the corruption and inefficiencies of this now-outdated system and rejecting it accordingly. However, as a result of the rampant market orientation of the Koizumi reforms progressively disassembling that system, the very foundations of people’s lives have been shaken, spurring unease at increasing social disparities. Protesting against such a divided society enabled the DPJ to carry the 2007 Upper House elections.

There is in fact no contradiction between these two DPJ positions. Seeking a more egalitarian society while also calling for lifestyles premised on individual autonomy rather than dependence on government discretion and patronage are quite compatible positions. It could even be said that they form a necessary pair.

The key issue is that the foundations and conditions underpinning the public’s desire for social security and safety nets are changing. It might appear that the LDP which won the high-theatre 2005 elections transformed itself into an urban-based party, while in the 2007 Upper House elections, the DPJ, which benefited from the single-seat constituency backlash, became a rural-backed party. However, a look at the types of occupations of both parties’ supporters reveals that this has not been the case. There has been a shift in LDP supporters toward management and on-site occupations, many of which are found in agriculture, forestry and fisheries. The DPJ support base, by contrast, has shifted to freelancers, office workers and technical workers, evidence of an urban support base. DPJ supporters nevertheless evince an increasingly strong welfare orientation.

In other words, there is increasingly little truth to the received wisdom that livelihood safeguards are sought by the uncompetitive rural sector while urban white-collar workers stress competition and efficiency and prefer small government. As we have long pointed out, the spread of new social risks in relation to employment and nursing care, etc., has created a growing need for public safety nets in the urban sector. At the same time, as observed above, the group with these needs is the same group that rejects livelihood safeguards where they are provided on the basis of administrative patronage and discretion. The real reforms in the years ahead will not be directed at realizing the small government sought by urban residents, but rather at developing the safety nets to deal with the risks faced by those residents.

(b) Making the opposition axis function

Growing numbers of voters embrace the apparently contradictory positions of wanting a welfare society while remaining deeply suspicious of government. Political parties need to develop visions that speak to these voters. If parties respond to the rural backlash against reform excesses by returning to the traditional courting of interests, they are likely conversely to alienate such voters. At the same time, given the enormous degree of suspicion with which the government is currently regarded, seeking to realize a big welfare state supported by a substantial tax burden is hardly an immediately feasible scenario, and could also all too easily endanger individual autonomy.

As of around the mid-1990s, various possibilities have been suggested in terms of creating a welfare society that doesn’t spawn a bloated administration and does support individual autonomy. One such vision was the “Third Way” once proposed by European social democrats. This “Third Way,” which comprised neither a centralized welfare state nor neoliberalism, sought to constrain the growth of social disparities not through income guarantees but rather by using nonprofit organizations and other such bodies to set in place the conditions for social participation. While this vision attracted reasonable attention in Japan, it could not be said to have penetrated sufficiently into actual politics.

Why is that?

When aftershocks from the recruit scandal shook the political world and as the collapse of the economic bubble spread disillusion over the traditional system, Japanese politics responded with a reform boom that focused not on political but rather on structural reform. Those economic commentators who had once praised the traditional Japanese system converted overnight to market advocacy, while politicians were vociferous in their intentions to tear that system down. Amidst the uproar, visions seeking a point of equilibrium between redistribution and growth were sidelined as vague and tepid.

Now, however, as a result of the reforms instituted by the Koizumi and Abe administrations, a massive 64 percent of the population believe that the gaps between the rich and the poor, and between urban and rural areas, have widened. A return to the traditional Japanese system is, of course, impossible. This stalemate in Japanese politics is reminiscent of the U.S. and the United Kingdom in the early 1990s when the neoliberal drive for small government stalled, prompting the emergence of the “Third Way” discourse.

Could this be the late emergence of our own “Third Way?” Here we must recall the differing realities of Japan and of Europe as the originator of the “Third Way” concept. Because Europe was struggling with rising social security spending spurred by high unemployment rates, the slogan in the “Third Way” discourse was “jobs not welfare.” The idea was to draw people into labor markets through means such as vocational training, counselling and childcare services, thus holding down administrative costs and increasing individual autonomy.

In Japan, on the other hand, social security spending is relatively limited, with the focus rather on using public projects, protection and regulations to provide jobs in uncompetitive sectors in order to restrain social disparities. In other words, Japan has always sought “jobs not welfare.” Moreover, given a system not of income redistribution based on consistent principles, but rather of opaque and arbitrary job redistribution underpinned by administrative discretion and interest-based politics, it is hardly surprising that the public’s distrust of government has risen to an extreme. Now, with this particular job redistribution system declining and society greying, people have no choice but to seek new safety nets.

3. Prospects for party politics

The emergence of some measure of separation in the respective policy preferences of LDP and DPJ supporters means that the preconditions for policy-based party politics are now in place. Having successfully negotiated the Koizumi structural reform era, a particular segment of the population that benefits from neo-liberal policies has also taken shape to some extent. As is clear from the survey results, this group have been newly incorporated into the LDP support team. In that sense, Koizumi’s strategy of courting urban voters arguably achieved some success. Victims of structural reform, on the other hand, are now pinning their hopes on the DPJ in the face of serious malaise over the future. If the LDP and the DPJ intend to create a policy-based two-party system, their mission must be to develop policies that are faithful to their supporters’ wishes. Clarification by the political parties of their respective policy axes would enable the public to make meaningful choices in the next elections. While opposing the neo-liberal policies of the Koizumi era, we believe that the structural reforms of that era created a space for policy debate—namely, a two-party split—that represents a step forward for Japanese party politics.

With this emergence of a basic direction, what will be the key points we should take note of in pursuing political debate? The first will be a departure from divisive politics. Back in the Koizumi era, there was extensive use of extremely simplistic slogans striking out at rivals and encouraging confrontation—calls, for example, for the transferral of power and initiative from the public to the private sector and for destroying the old conservative forces of resistance. These catchphrases were effective in realizing specific projects such as the privatisation of Japan’s postal services, but they also ran counter to the deepening of policy debate. Policy is neither a means of achieving Utopia nor a weapon for slaying an opponent. It is a tool for gradually resolving contemporary issues, and every policy has both effects and costs. All parties need to encourage realistic debate on their policies.

Second, a serious attempt must be made to address government distrust. During the Koizumi years, the LDP actually inflamed government distrust as means of gathering support. This is a self-destructive method as far as politics is concerned. Looking at the sloppy management of pension records, people’s distrust of the bureaucratic system is only natural. Breaking down mechanisms that make much of officialdom and little of the people, as evinced in a pension system under which beneficiaries must apply in order to receive their pensions, is a key task for all political parties. However, demolishing the bureaucratic system inclusive of its function in drafting and implementing policy would hamper policy implementation regardless of which party takes power. Rather than simply attacking bureaucrats, the challenge for political parties will be to enhance bureaucratic ethics and motivation. The duty of politics is to set out specific policy goals on the basis of a clear philosophy and values. To reiterate an earlier point, a policy line that does no more than call for more welfare services while scraping together the necessary funds by curtailing wasteful spending is not going to boost bureaucratic motivation.

Third, we need concrete discussion of policy results and costs. As noted earlier, the Koizumi era saw redistribution to the strong glorified as reform. Unclear terms such as ‘reform’ should no longer be used. We should not say social security reforms, but instead refer clearly to reductions in medical care and nursing care spending. Rather than talking about reforming local allocation tax, we should talk about reducing the amount of tax that the central government allocates to local governments. And, having clarified the expected consequences of these policies, we should let the public decide on their relative pros and cons. For example, there has recently been criticism about emergency patients being denied admission by hospitals, but this is by no means an issue of doctor neglect. It goes back to policy, and restricted medical care spending and the shortage of doctors. The time has come to free the public from the spell of reform and launch concrete discussion of exactly what kind of society we want to create.

Moreover, if child allowances and income subsidies for farming households are going to be an issue, how much of the budget will be earmarked for these? If cutting back on wasteful spending is a key issue in terms of fiscal sources, from where will that waste be curtailed? These points need to be made clear. In fact, identifying waste will not be such a simple call. Major cuts have already been made in big spending areas such as public works and local allocation tax, to the extent that any further reductions would make it impossible for local governments to meet the national minimum and sustain employment. The DPJ’s call for a welfare state is a welcome trend, but it will make high-level policy debate even more necessary if the public and the bureaucracy are to be brought on board.

The process of trial and error in political reform and in the reorganization of Japan’s political parties that began in the 1990s has now entered its final phase. We are finally seeing the emergence of a two-party system of a global standard that sets a conservative party with neo-liberal preferences on the right and a liberal social democratic party calling for a welfare state on the left. Whether such a competitive political party system takes hold will be questioned in the next general election. At the same time, there are certainly many politicians in both the LDP and the DPJ who will feel uncomfortable with these particular party lines. It would probably be a good thing if the clarification of party lines were to see dissenting politicians shift to their ‘natural’ parties. Policy debate sufficiently rigorous to spur that degree of change is just what Japan currently needs.

Jiro Yamaguchi is professor of public administration at the Graduate School of Law, Hokkaido University. Publications include Okura-kanryo shihai no shuen [The end of control by Ministry of Finance Bureaucrats], Ittoshihai-taisei no hokai [The breakdown of single-party control], Blair jidai no Igirisu [The United Kingdom under Blair], Naikaku seido.[Cabinet System], Posuto sengo seiji e no taikojiku [Alternative to Post-Democracy in Japan]. Edited works include Nihon-seiji: saisei no joken [Japanese politics: The conditions for revival] and “Kyosha no seiji” ni taiko suru! [Resist “politics of the strong”!]

Taro Miyamoto is a graduate school professor at Hokkaido University. Publications include Shimin shakai-minshushugi no Chosen [Challenges of civil society democracy] (co-authored, Nihon Keizai Hyoronsha) and “Posuto Fukushi-kokka no Gabanansu” [Post welfare state governance], Shiso, No. 983.

The Japanese original of this article was published in Sekai on March 2008. Posted at Japan Focus on March 28, 2008.