Starving the Elephants: The Slaughter of Animals in Wartime Tokyo’s Ueno Zoo

Frederick S. Litten

“Speaking of wartime Ueno Zoo, what comes to your mind? ‘The elephants were killed!’ Yes, that’s right.” So begins Sayōnara Kaba-kun (Farewell, Hippo; Saotome, 1989), a picture book for grade school children.

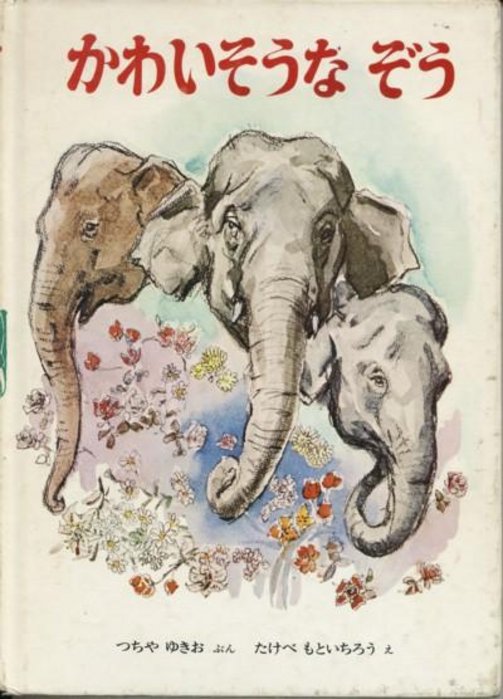

There are numerous Japanese depictions and stories of the wartime slaughter of animals at Ueno Zoo: from the enormously popular and influential picture book Kawaisōna Zō (The Pitiful Elephants) (Tsuchiya & Takebe, 2009)–originally published by Tsuchiya Yukio as a short story for children in 1951, then as a picture book in 1970 with 163 editions to date–to the recent TV drama Zō no Hanako (The Elephant Hanako; Kōno & Terada, 2007). The story has also travelled outside Japan, with two English and one French translations of Kawaisōna Zō1. Most of these depictions portray the slaughter of the animals as motivated by the wish to protect humans from more or less immediate danger and accept the starvation of the elephants as unavoidable. Scholarly studies have been published so far only in Japanese and tend to be critical only in some points (e.g., Hasegawa, 2000; originally published in 1981), if at all.

Cover of “Kawaisōna Zō”, the most popular version of the myths about the Ueno Zoo slaughter in 1943

This study deals with what really happened at Ueno Zoo in the summer of 1943, how it came about, and how unique this event was. To put it into context I will present relevant information also from the years before and after the (main) slaughter and will look briefly at wartime developments at several zoological gardens in Europe and Japan.

The Setting

Ueno Zoological Garden is located in the Ueno district, Taitō ward, Tokyo. In 1882 it opened as the first zoo in Japan; in 1924 control passed from the Imperial Household Agency to Tokyo city.2 With an area of 14.3 ha today, Ueno Zoo is rather small, but because of its location in the capital and connection with the imperial family it plays a central role in the history of Japan’s zoological gardens.

Ueno Zoo’s director from 1937 to 1941 and from 1945 to 1962 was Koga Tadamichi (1903-1986), whom Kawata (2001b, 310) refers to as “Japan’s Mr. Zoo”. Koga had graduated in veterinary medicine from Tokyo Imperial University and began working at Ueno Zoo in 1928.

From August 1, 1941, to October 10, 1945, the acting director was Fukuda Saburō (1894-1977). A graduate of Tokyo University of Agriculture, he had worked at Ueno Zoo since 1922 as a technician and would continue to do so until 1953 (Tōkyō-to Onshi Ueno Dōbutsuen, 1982a, 182; this source will be abbreviated thereafter as “Ueno, 1982a”).

Prelude: 1936-1939

Looking back on 1936, people in Japan spoke of “three big incidents”: the “February 26 Incident” (“Niniroku Jiken”), the “Abe Sada Incident”, and the “Black Leopard (Escape) Incident” (Komori, 1997, 53). The first and by far most significant one refers to an attempted coup d’etat on February 26 by an army faction, which only was thwarted a couple of days later on orders from Emperor Hirohito (Gordon, 2003, 198).

On May 18, Abe Sada, a low-ranking geisha and prostitute, strangled her lover to death, cut off his genitalia, and carried them with her until she was arrested on May 20. This case horrified, and fascinated, Japan and would continue to do so for decades to come (Johnston, 2005), most famously in Ōshima Nagisa’s movie Ai no korīda (In the realm of the senses; 1976).

Compared with these incidents and with other events in 1936, such as the Olympic Games in Berlin or the signing of the Anti-Comintern Pact between Germany and Japan, the “Black Leopard Incident” was a minor one. In the early morning of July 25, a keeper at Ueno Zoo noticed that a black leopard, a recent gift from Siam (Thailand), was missing. Police and Kenpetai (military police) were called in and a large-scale search started. Early in the afternoon the leopard was discovered cowering in a manhole of the sewers adjacent to the zoo, was captured and brought back to her cage. The incident, although lasting only about 13 hours, seems to have made quite an impression on Tokyo residents (Komori, 1997, chapter 11) and presumably contributed to later concerns about animals escaping from their cages.

At Ueno Zoo, Koga and Fukuda were reprimanded for this incident and administrative reform was initiated when it turned out that there was no formal “zoo director” with corresponding rights and responsibilities (Kawata, 2001a, 1273; Ueno, 1982a, 182). Such a position was created and filled in March 1937 by Koga. The memory of this incident was further kept alive by security drills on the anniversary of the escape (Ueno, 1982a, 152).

The outbreak of full-scale war between Japan and China in July 1937 did not have much of an impact on Ueno Zoo, except that it would receive more animals sent by Japanese officers from the occupied areas (e.g., Ueno, 1982a, p. 151). The air-raid drills were not taken very seriously, as China did not have the capability to strike Japan and the battles that year with the Soviet Union at Nomonhan were played down to the public (Gordon, 2003, 206).

Preparing for Emergency in Europe: 1939-1941

The situation was different in Europe. The war, which broke out there in September 1939, was taken more seriously on the homefront, with tragic consequences for some zoo animals.

As Lutz Heck, the director of Berlin Zoo at the time, relates in his memoirs, many people were afraid of what would happen in the case of air attacks. “The worse the ignorance, the more grotesque shapes the fears took on.” (Heck, 1952, 135). Most people outside the zoos were afraid of lions, tigers and poisonous snakes, whereas the zoo’s staff was more concerned about elephants and bears running loose. According to Heck (1952, 139), soon after the outbreak of war the military ordered all lions, tigers, leopards and bears in west German zoos to be shot. However, in contrast to his account, this did not happen, for example, in Munich (Gottschlich, 2000, 136) and Frankfurt am Main (Zoo Frankfurt am Main, n.d.) where lions were only shot later in the war and after air attacks. In Wuppertal, on the other hand, on May 15, 1940, three brown bears, two polar bears and five lions were shot by order of the city administration, before any air raids occurred (personal communication, U. Schürer, August 24, 2009).

Such events were not confined to Germany. At London Zoo “all poisonous snakes and invertebrates” were killed at the beginning of the Second World War out of fear that they would escape during an attack (Barrington-Johnson, 2005, 123). On April 19, 1941, four days after a German air attack on Belfast, 33 animals (lions, bears, etc., but not the elephants) were shot at Belfast Zoo (“Belfast zoo,” 2009, March 23); the zoo itself was never hit.

The widespread fear that air attacks might free dangerous animals from zoos was even used for a German movie, appropriately entitled Panik (Panic). Harry Piel, a well-known actor and director, started shooting the movie in 1940; the plot about a bombed zoo was soon reported in the official Nazi newspaper Völkischer Beobachter (Hacker, 1940, October 13). An article about the Japanese government symbol, the kiri, or Paulownia tree, appeared on the same page, so it is even possible that this information found its way to Japan.

Garbled information from Berlin certainly reached Ueno Zoo one year later. Not for the first time, Berlin had been attacked by British bombers on the night of September 7-8, 1941. Shortly thereafter a reporter from the Japanese newspaper Asahi Shinbun told Fukuda that during this attack the elephants in the Berlin Zoo had been killed and that other animals had had to be shot (Fukuda, 1982, 81). However, the one time in 1941 that bombs fell on Berlin Zoo, an antelope was the only animal to die (Heck, 1952, 142-143). The elephants and many other animals in Berlin Zoo were killed by the air attacks of November 22 and 23, 1943, and the BBC at the time reported incorrectly that animals had escaped from the zoo during the bombardment and had been machine-gunned in the streets (Heck, 1952, 168).3

Preparing for Emergency in Japan: 1941-1942

Japan in 1941 still did not really feel as if it were at war. Fighting in China continued, but did not have much of an impact on Japan itself. However, supply problems emerged, and war with the United States was on the horizon. Preparations had to begin.

Besides intensifying air-raid drills, Ueno Zoo decided to economize. While director Koga was in Manchukuo (Fukuda, 1982, 92), it was decided on February 18, most likely by Fukuda, to shoot four bears thought to be surplus (Fukuda, 1982, 76).4 A couple of months later Koga, who had returned to Japan in the meantime, was drafted, and Fukuda became acting director on August 1, 1941 (Fukuda, 1982, 92).

Only just appointed, he was asked by the regional veterinary department of the army to present a plan on how to deal with the possibility of animals escaping during an air attack (Ueno, 1982a, 165). On August 11, 1941, he submitted his “General Plan for Extraordinary Measures in Zoos”, covering not only Ueno Zoo, but also Inokashira Zoo and Hibiya Park in Tokyo (Tōkyō-to Onshi Ueno Dōbutsuen, 1982b, 729-732; this source will be abbreviated as “Ueno, 1982b” in the following).

According to this plan, the zoo animals were divided into four categories5: bears, the big cats, coyotes, striped hyenas, wolves, hippopotami, American bison, elephants, monkeys (mainly Hamadryas baboons), and poisonous snakes were listed in category one (“most dangerous animals”). In category two (“less dangerous animals”) could be found raccoons, badgers, foxes, giraffes, more monkeys, kangaroos, crocodiles, deer, eagles, and emus. Category three (“domestic animals in general”) included water buffaloes, goats, turkeys, pigs, and so on, while category four (“else”) explicitly mentioned only songbirds and turtles.

The preferred means of dealing with these animals was to be poison. A table was attached to the report, detailing the amounts of strychnine nitrate or potassium cyanide deemed necessary to kill the animals in the first three categories, including the exact doses for each of the three elephants, for the hippopotami and for the snakes. If there was not enough time to administer the poison, two Winchester rifles and keepers trained to shoot the animals would have to be used. However, because shooting might negatively affect “people’s hearts” and other animals at the zoo, and was considered less effective, this was to be strictly the fallback method.

When the air-raid alarm sounded, the “General Plan” called for preparations to begin for dealing with the animals of categories one and two. At the commencement of the air raid these preparations should have been completed and preparations for dealing with the animals of category three should be started. Depending on whether or not the attack resulted in or threatened to cause damages to the zoo, the animals of category one and two should be dealt with in that order; if necessary, this would extend to the animals of category three.

As a precaution, Fukuda also asked the local detachment of the Kenpeitai if they were willing to provide assistance in case of an emergency; they agreed and inspected the zoo in order to be prepared for such an event.

The first chance to implement at least some provisions of the August 11 plan came only in 1942. On March 5, the air-raid sirens briefly sounded, but nothing happened except that the visitors were asked to wait outside until the end of the alert (Ueno, 1982b, 734). On April 18, 1942, in the “Doolittle Raid”, the first American air attack on the Japanese main islands, 16 B-25 bombers started from an aircraft carrier and attacked Tokyo and some other places (Chun, 2006). Ueno Zoo remained unharmed, but one of the American planes flew quite low overhead (Fukuda, 1982, 83-84). In his official report (Ueno, 1982b, 734-735), Fukuda claimed that stage 2 of his 1941 plan had been completed when the plane was spotted, i.e., preparations to deal with the animals in categories one and two had been completed, but there is no mention of this in his memoirs. According to Fukuda, another, albeit false, alarm on April 19 also led to the completion of stage 2 of his plan (Ueno, 1982b, 735).

Soon, everyone assumed that the attack of April 18 would remain an isolated case–in fact, the next attack on Tokyo occurred only on November 24, 1944– and life returned to normal in this regard. In the case of Ueno Zoo, which celebrated its 60th anniversary in 1942, visitor numbers remained close to record numbers, with 3,077,435 paying visitors; soldiers, for example, did not have to pay (Ueno, 1982a, 167).

The Slaughter and the Memorial Service: August and September 1943

By summer 1943, the military situation had changed dramatically for Japan. Except in China, it was now retreating on most of the fronts. Even in Japan itself, propaganda had changed from katta, katta (We’ve won, we’ve won) (Ueno, 1982a, 157) to kessen (decisive battle) and its homonym kessen (bloody battle) (Earhart, 2008, 375). Commodity shortages really began to hurt, as can be seen in various drives to procure metals from all possible sources, including from the benches at Ueno Zoo (Ueno, 1982b, 737). For those Japanese leaders familiar with and objective about the situation, it became necessary to prepare the population for more hardships. As part of such measures, Tokyo city and Tokyo prefecture were merged into Tokyo metropolis, and a new governor, Ōdachi Shigeo, started work on July 1, 1943 (Ueno, 1982a, 168).

On August 16, 1943, Fukuda was called into the office of Inoshita Kiyoshi, the section chief for Tokyo’s public parks and thus his immediate superior. There he also met Koga who, after a tour-of-duty in South-East Asia, had returned to teach at the Army Veterinary School in Tokyo. Fukuda noted in his diary (quoted in Ueno, 1982a, 170): “… the section chief told us, on the basis of an order by the governor, to kill the elephants and wild beasts [mōjū] by shooting. (Killing by poison)”.

Koga wrote in his memoir Dōbutsu to watashi (Animals and I; serialized in the monthly journal Ueno; quoted in Ueno, 1982a, 170-171):

At the time I felt ‘Oh, finally things have come to this’ … Concerning this decision we could do nothing but hang our heads. Although I heard this afterwards, it was because at the time people all still thought the war would be won. But Ōdachi, who had been mayor of Singapore … before becoming governor of Tokyo, seems to have already known the true war situation. When he returned to the motherland to become governor of Tokyo and saw the attitude of the people, he seems to have felt keenly that he had to open the people’s eyes to the fact that this was not the way to go, that war was not such an easy affair. And Ōdachi chose to give the people the warning not by expressing it in words, but by the disposal of the zoo’s wild beasts.

That Ōdachi had ordered the slaughter was also reported in 1954 in Tosei jūnen shi (Ten years history of metropolitan government; quoted in Hasegawa, 2000, 21-22). According to this source, Ōdachi ordered the zoo officials to kill the animals to “shock” Tokyo’s residents. It was also argued that, no matter how vigilant the zoo would be, the residents of Tokyo would still fear an escape by wild beasts in case of an air attack.

Although Fukuda brought a list of the animals to be killed to the meeting on August 16 (Fukuda, 1982, 96), he initially attempted to save at least some of his charges.6 On August 17 he noted in his diary (quoted in Ueno, 1982a, 171) that after a phone call with the section chief, who forbid him to travel to Nagoya’s Higashiyama Zoo or Sendai Zoo, he sent letters to the directors of these zoos asking whether they would accept two leopards and two black leopards in Nagoya and one elephant (see below) in Sendai (Ueno, 1982b, 738). However, the idea of evacuating animals was dismissed by Ōdachi on August 23, even though Sendai Zoo was already preparing the transfer (Ueno, 1982a, 172). For Ōdachi the point was not to save the animals, it was to rouse the people of Tokyo (Miller, 2008). But did anyone consider presenting the evacuation of the animals, especially the elephants so beloved by children, as a good example for the evacuation of the children that would surely become necessary in the case of sustained air attacks?

On the same day he sent the letters to Nagoya and Sendai, Fukuda also started following his orders. These seem to have included the provision that the disposal would have to be finished within a month (Fukuda, 1982, 96). As to the method, according to Fukuda (1982, 96), shooting the animals was not allowed because the noise might worry the residents around the zoo. However, the entry in his diary, which first says shasatsu (killing by shooting) and only later and in parentheses dokusatsu (killing with poison), sheds doubt on whether this detail actually originated from the governor’s office. Fukuda himself had stated in his plan two years ago that poisoning was preferable to shooting. On the other hand, he does not seem to have had any problems when the four bears were shot in February 1941. With the zoo being open every day, moreover, the disappearance of more and more iconic animals could not be covered up for very long, despite notice boards about “construction work” being set up on August 28 (Ueno, 1982a, 176). And finally, killing the animals was meant to become known to the public anyway, otherwise it would not have fulfilled its propaganda purpose. While it seems to have been universally accepted that shooting the animals was not an option, there remain grave doubts.

Concerning the methods actually employed to kill the animals, there are some discrepancies between the official documents (Fukuda’s final report of September 27, 1943, is reprinted in Ueno, 1982b, 739-740), where only poisoning and starving are mentioned, Fukuda’s memoir (Fukuda, 1982, 96-98) and the description in the history of Ueno Zoo (Ueno, 1982a, 173-177, 180). The following is based on the two latter sources; the elephants will be treated separately:

August 17: a North Manchurian brown bear and an Asian black bear (Japanese) were poisoned (the poison, strychnine nitrate, was provided by the Army Veterinary School and was mixed into the food);

August 18: a lion, a leopard, and an Asian black bear (Korean) were poisoned;

August 19: a North Manchurian brown bear was given poison, then the coup de grâce was delivered with a lance;

August 21: an Asian black bear (Korean) was given poison, then stabbed; another Asian black bear (Japanese) had not been fed for three days already and was strangled with a rope while sleeping;7

August 22: two lions were poisoned, the tiger and the cheetah were killed (no further information is provided);

August 24: a polar bear died, presumably of starvation;

August 26: a black leopard and a leopard were poisoned; the head of the rattlesnake was pierced with wire, then a heated wire was tied around the neck and pulled, but the snake did not die until the next morning, after 16 hours, when a thin cord was used around the neck;

August 27: the head of the python, who had been fed two rabbits not even a week ago,8 was cut off and she died after a while; the sun bear was poisoned; a black leopard and a leopard were strangled with wire rope;

August 29: a polar bear, who had not yet died of starvation, was strangled with a wire; an American bison was roped and killed by blows to the head from a pickaxe and a hammer;

September 1: the second American bison was killed in the same way as the first;

September 11: a leopard cub, who had only been born in March, was poisoned.

In total, 24 animals (plus three elephants) were killed. After necropsies at the Army Veterinary School (Ueno, 1982b, 740-741) the carcasses were stuffed or skinned, the bones to be interred at the zoo’s monument for dead animals (Komori, 1997, chapter 13); a few were buried immediately.

On September 2, the metropolitan government officials sent a notice to newspapers about the “disposal” of the wild beasts at Ueno Zoo and the intention to hold a memorial service (ireisai) for them on September 4 (Ueno, 1982a, 177). This event was not only attended by several high-ranking Tokyo officials, among them the governor himself, but also by hundreds of school children, who had been specifically targeted as an audience (Hasegawa, 2000, 23).

A newspaper for children, the “Shōkokumin shinbun”, reports on the memorial service

The animals, people were told, were martyrs for the country. As section chief Inoshita explained (Ueno, 1982a, 177): “I want you to think deeply about the severity of the situation that made such extraordinary measures necessary.” Or as acting zoo director Fukuda told the Mainichi shinbun (Zen mōjū, 1943, September 5):

At a time of decisive battle [kessen], this is actually an unavoidable measure that must naturally be taken. … [The animals] went to their deaths to let the people know in silence about the unavoidability of air attacks. … The method of disposal? Although I don’t really want to talk about it anymore … the carnivores were given poison. The others were disposed of by appropriate means ….

What seems to have been left somewhat vague was the direct connection between any air attacks in the future and the need to kill animals “prophylactically” now. Their “martyrdom”, however, fit in well with the beginning of the gyokusai (“shattering like a jewel”), or death with honor, propaganda celebrating suicidal behavior at the front, first encountered after the loss of Attu, one of the Aleutian islands, in May 1943 (Earhart, 2008, 375ff.). Killing zoo animals prophylactically was not unique to Japan, but using this as a propaganda spectacle–in fact, timing it for propaganda reasons and not because of any impending attack–was highly unusual, to say the least. In other countries, such methods would probably have been seen as defeatist or at best useless.

Were they useless in Japan? One of the children’s letters that poured in from all over Japan gave vent to a rage about “America and Britain that caused these animals to be killed” (Fukuda, 1982, 102). But other children simply pitied the animals–and the keepers that had to kill them (Fukuda, 1982, 102). In the end, it probably did not make an iota of difference for Tokyo’s, to say nothing about Japan’s, preparedness for the reality of air attacks. Showing Harry Piel’s movie Panik, finished at that time but promptly banned for being too realistic in its depiction of air attacks (Bleckman, 1992, chapter “Keine Panik”), might have been more effective, but at that time Japan did not import movies anymore.

Starving the Elephants: August and September 1943

Elephants had been a sensation in Japan for quite some time. In 1728, an elephant from Vietnam was brought from Nagasaki to the Tokugawa shōgun in Edo with an entourage of “no fewer than seventeen people at its smallest” (Miller, 2005, 281). At Ueno Zoo, too, elephants were extremely popular with the zoo visitors. After the Great Kantō Earthquake, the Imperial Household Ministry had decided to have the elephant at Ueno Zoo shot by Tokugawa Yoshichika, a marquis and famous hunter, to preempt the animal, considered ill-tempered, from causing damage after another earthquake. (At the time Ueno Zoo was still imperial.) The marquis, however, declined to shoot him because he had been a present from the King of Siam in 1888. The elephant was then taken in at Hanayashiki Park in nearby Asakusa, where he died in 1932, chained on all four legs (Komori, 1997, chapter 8).

In 1924, Ueno Zoo was given to Tokyo city as a “gift” commemorating the marriage of crown prince Hirohito. But there were no elephants and the elephant house stood empty, so in October Tokyo city bought a male and a female Indian elephant: Jon (“John”, about six years old) and Tonkī (“Tonky”, about four years old). Both were used to humans and were trained to do tricks, but John later became somewhat aggressive and rarely performed for the visitors (Komori, 1997, chapter 9).

In June 1935, the Thai State Youth Organization presented Ueno Zoo with another female elephant, named Hanako in Japan, but also called Wanli or variations thereof, presumably a reflection of her original Thai name (Fukuda, 1982, 59). These three elephants, especially Tonky, became among the main attractions of Ueno Zoo, and not only for children.

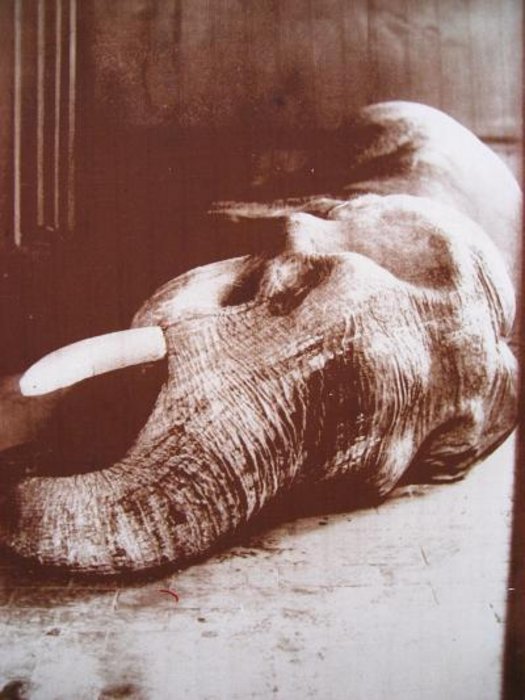

Wanli (left) and Tonky (right) in August 1943, shortly before they were “disposed of”

As discussed above, the three elephants were deemed especially dangerous in case of air attacks in Fukuda’s plan of August 11, 1941, so it was no surprise that the slaughter should include the elephants. But in John’s case, the death sentence was already pronounced before the meeting of August 16, 1943. He had been aggressive again and his front feet had already been chained. Shooting him was not considered an option as this would have caused the public to become uneasy (but see above), so he was put on a starvation course9 on August 13 based on an earlier understanding between Fukuda and Inoshita (Fukuda, 1982, 108; Ueno, 1982a, 170)10.

John has collapsed on August 17, 1943

When Fukuda tried to save some animals, the only elephant he really cared about was Tonky (Fukuda, 1982, 98), whom he wanted to send to Sendai Zoo. After this attempt failed, according to Fukuda’s memoir (1982, 99),

at first, it was decided for the Army Veterinary School to take responsibility and proceed with measures concerning only the elephants, who were to be used as reference material. They decided to try to use potatoes injected with potassium cyanide and injections with strychnine nitrate. However, the elephant(s?) soon noticed which potatoes were poisoned and threw them back.11 Even though the injection was made behind the ears, where the skin is the thinnest, the needle broke and thus the objective could not be attained. Therefore, the Army Veterinary School said that they would withdraw. For the zoo there remained only the method of stopping to feed, i.e., starving them.

These attempts should have been made on or about August 24. That John died on August 2912 and that Hanako and Tonky began to be starved on August 25 is mentioned only later on the same page.

Yet there are several problems with this story. First, it does not correspond with the version Fukuda gave in his Dōbutsu monogatari (Zoo Stories, published in 1957 and quoted in Ueno, 1982a, 177-179). Neither the Army Veterinary School nor any attempt at injecting the elephants with poison is mentioned there at this stage; only the potato story is recounted. Moreover, Fukuda gives the impression that starvation began for all three elephants a day later.

In addition, in his memoir Fukuda (1982, 73) noted on December 14, 1939: “The elephant Tonky is unwell and given an injection.” It therefore seems that this means of delivery was available after all.

The 100 Years History of Ueno Zoo does not quote anything about such attempts by the Army Veterinary School during August 1943 from Fukuda’s diary, although mention is made there of talks with Army Veterinary School people, e.g., on August 23 (Ueno, 1982a, 172). Instead, the diary entry for August 25 refers to an offer by phone from Koga Tadamichi to let the Army Veterinary School kill the elephants by three different methods for research purposes because elephants might become useful for the military. When Fukuda discussed this with the section chief, Inoshita told him not to evade his responsibility (Ueno, 1982a, 175).

According to Fukuda’s diary (Ueno, 1982a, 180), the people from the Army Veterinary School did come on September 14, when only Tonky was still alive. They tried to make Tonky drink water laced with potassium cyanide, but failed, then took blood (saiketsu shite) and left.13 Whether any attempt was made to feed all or some of the elephants poisoned potatoes is left open. In his memoir Fukuda (1982, 100) claims this was attempted unsuccessfully (again) and that Koga had taken the initiative to hasten Tonky’s end.

All this points to one conclusion: From the beginning Fukuda intended to starve John to death. How he initially intended to deal with Hanako remains vague; perhaps she was given the poisoned potatoes. When the attempt to send Tonky away failed, her fate was sealed as well.14 Only after Hanako’s death on September 11, thought to have been due to autointoxication (Ueno, 1982a, 179), did the people of the Army Veterinary School attempt to kill Tonky by poisoning her water. Yet, if it was possible to take blood from her, and if it had been possible to give Tonky an injection a couple of years earlier, why couldn’t they, or rather why wouldn’t they, inject her (and John and Hanako) with poison? And why, back in 1941, had Fukuda confidently listed the amounts of strychnine nitrate and potassium cyanide needed to kill each of the elephants if it would not have been technically possible? Instead of having no choice but to starve the elephants, injecting them with poison was simply not attempted. As discussed, shooting the elephants would have been feasible, too. Even if there had been a direct order by the governor not to shoot the animals, one could always have argued, in the elephants’ case, that they were beginning to go wild and simply had to be shot.

Two further points need to be made: The memorial service for the slaughtered animals–including all three elephants!–on September 4 was held while Hanako and Tonky were still starving–literally a stone’s throw away. The elephant house had been covered at that time with a striped bunting (Ueno, 1982a, 177).

The memorial service on September 4, 1943; notice the striped bunting

And no source mentions whether the elephants made any noise, especially after being officially dead. One might think that a hungry and thirsty elephant trumpeting would be as loud as a gunshot–and the zoo was open to visitors daily.

Tonky was the last to die. After four weeks of hunger and, as it is reported, repeated attempts to get food by showing off her tricks, she died on September 23, 1943. In what looks like an established modus operandi, however, she was not the last animal at Ueno Zoo to be intentionally starved to death.

Starving the Hippopotami: March and April 1945

The supply situation became critical as the war turned relentlessly towards the Japanese main islands. At Ueno Zoo, food and fuel also became ever more difficult to obtain. At several points after the slaughter of August/September 1943, zoo animals were killed to be used as food (Ueno, 1982a, 189) or died because of a lack of food and heating. Even the doves were “dealt with” in spring 1945 by no longer feeding them (Fukuda, 1982, 105); 35 cranes and other birds and two Reeves’s Muntjacs were “disposed of” on April 21, 1945 (Ueno, 1982a, 195).

The animals that had survived the slaughter and consumed the greatest amount of food were the hippopotami. One male died from a gastrointestinal inflammation on March 18, 1944, but the female Kyōko (at Ueno Zoo since 1919) and the male she had borne at the zoo in 193715 remained alive. After the devastating air raid on Tokyo on the night of March 9-10, 1945, Fukuda decided on March 19 to starve both due to lack of food (Ueno, 1982a, 194; Fukuda, 1982, 105). Neither source gives any indication whether alternative methods to kill them were attempted, or at least contemplated. The male died on April 1, and Kyōko only on April 24 (Ueno, 1982a, 194).

Kyōko and her child

It might again be instructive to look at an example from a society as brutalized as the Japanese was at the time: Soviet Leningrad during the Second World War (Ganzenmüller, 2007). On September 8, 1941, the German troops had closed the ring around Leningrad and a siege began that would last until January 27, 1944. Leningrad Zoo had managed to evacuate some animals to Kazan, others – such as the elephant Betti – died during the initial German bombardment in September 1941 (Denisenko, 2003, 194, 202-203). However, numerous animals remained, among them several carnivores and Krasavica (The Beautiful), a hippopotamus. During the following years, when approximately one million people died in Leningrad from hunger, cold or injuries, Krasavica’s keeper, Evdokia I. Dašina, kept her alive, bringing water from the nearby Neva, even stepping into the dry pool to hug the animal and calm it down. “Thus they lived until victory” (Denisenko, 2003, 206). And so did the other animals.

Krasavica and her keeper E. I. Dašina

Aftermath: Tokyo, Nagoya, and the “Elephant Train”

The end of the war in September 1945 did not mark the end of the problems for Ueno Zoo. Not only would a scarcity of food and fuel persist for quite some time for humans as well as animals, but the zoo also had lost most of its attractions. The only animals literally towering above the numerous ducks, pigs, goats and some monkeys were the giraffes (Ueno, 1982a, 197-198). Children who came to the zoo to see their beloved elephants found a propped-up wooden board cut roughly in the shape of an elephant.16 In the following years more animals arrived and in 1948 a children’s zoo with a “monkey train” (a children’s train seemingly operated by a monkey) would lighten the hearts of the young visitors (Komori, 1997, chapter 17), but the elephants were still sorely missed.

However, the rest of Japan had followed Tokyo’s example from August and September 1943. Beginning in October 1943, wild beasts and elephants were killed in all zoos, amusement parks, and circuses, although it seems that none of the other institutions used deliberate starvation.17 But not every zoo director accepted the order without resistance.

In autumn 1943, the military asked the mayor of Nagoya to make sure that all dangerous animals in Higashiyama Zoo were killed. Kitaō Eiichi, the zoo director, could prevent a wholesale slaughter only by agreeing to the death of a few animals (by shooting, poisoning, and strangling), and giving two lions away.

Still, public opinion, as expressed in newspapers, for example, demanded that all “dangerous” animals be disposed of. Kitaō replied that the cages were built sturdily enough; if they were destroyed, the animals within would die, too. Even while he was called a hikokumin (treacherous citizen), usually the point at which people gave up resistance, he persisted in protecting the animals.

After an American air attack on December 13, 1944, however, he had to concede. In accordance with an order by the Ministry of Home Affairs, military personnel and police shot seven lions, tigers, bears and leopards within 45 minutes. A few days later, another eight bears were killed (Senjika no dōshokubutsuen, n.d.).

Lions are shot at Higashiyama Zoo in 1944

The three elephants (another one had already died in February 1944) were not shot. The military insisted on it, but Kitaō turned to the head of the regional command’s army veterinary department and succeeded in saving the elephants. He argued that they were chained at the front feet anyway and that he would give monthly reports on their situation, so any measures could be taken as necessary.

That the army then set up a camp within the zoo turned out to be a blessing in disguise for the two surviving elephants, Erudo and Makanī. Kitaō’s staff was able to steal food from the military’s store and feed it to the elephants who thus survived the war (Zō no unmei, n.d.). The only other elephant still alive in Japan at that time died in early 1946 in Kyoto (Personal communication, K. Kawata, November 18, 2009).

In 1948, Tokyo’s children began clamoring for an elephant. Could Tokyo get one of the two surviving elephants from Nagoya? Discussions in January 1949 between Koga Tadamichi, who had returned to his post as director of Ueno Zoo, and Kitaō in Nagoya led to the result that Higashiyama Zoo would temporarily lend an elephant to Ueno Zoo. The elephants did not agree, however: it proved to be impossible to separate them without Erudo hurling himself violently against the doors.

But if the elephant would not come to Tokyo, the children would come to the elephant. On June 18, 1949, the first “elephant train” went from Tokyo to Nagoya, filled with children eager to see a real elephant again, or for the first time (Shōwa 20 nendai, n.d.). “Elephant trains” from all over the country converged on Nagoya and it is said that more than 10,000 children saw Erudo and Makanī that summer (Tetsudō shiryō Kenkyū-kai, 2003, 120).

Tokyo’s residents, though, would soon have the opportunity to see not one, but two elephants in Tokyo again. On September 4, 1949, Hanako18, a young elephant from Thailand, arrived at Ueno Zoo (Fukuda, 1982, 131), but was eclipsed by the gift of Indian prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru to Japan’s children as a result of a letter campaign: an Indian elephant called Indira. She arrived by ship on September 24 and was marched in the early morning hours of September 25 to Ueno Zoo, where she was greeted by about 2,000 people.

The arrival of Indira in 1949, as pictured in the anime “Zō no inai dōbutsuen”

The next day, the zoo was filled to capacity with about 10,000 people trying to see the new elephants (Komori, 1997, 95-96) – some of them certainly hoping that the past would not repeat itself.

Conclusions

The slaughter of animals at Ueno Zoo in 1943 was a tragedy that probably could not have been avoided entirely by the zoo’s acting director, Fukuda Saburō, but could certainly have been alleviated. As has been shown, similar “prophylactic killings” occurred outside Japan, although rarely. The sources that point to the governor of Tokyo, Ōdachi Shigeo, ordering the slaughter are credible. His motivation remains difficult to understand, although the dilemma mentioned by Hasegawa (2000, 25) and Miller (2008) between alerting the population of the dangers to come and still accepting the military’s propaganda and not sounding defeatist was real. Yet Hasegawa (2000, 26) is also correct in noting that a much better way would have been to disabuse the population of the notion that hand-dug air-raid shelters and a water bucket and a broom as fire-fighting equipment would be valid defenses against incendiary bombs, and to really prepare the city for the worst.

Fukuda comes across as quite deferential to his superiors, even anticipating their order in the case of John, although he seems to have tried to save at least Tonky and some leopards. But, as Kitaō’s example illustrates, there might have been one other avenue for him: talking directly to the army. Koga Tadamichi’s stance, however, is disappointing, too, in this context. I have deliberately not commented on the actions of the zoo keepers for there is no doubt that the ultimate power to make decisions within the zoo rested with Fukuda.19

What is inexcusable, in my opinion, is his choice of methods of killing: not shooting those animals that could not be poisoned, and to starve to death the three elephants, one Polar bear and, in 1945, the two hippopotami. Far from being the only option, this most cruel of methods could have easily been avoided. Why Fukuda chose to do so is difficult to understand. This is the black hole in the darkest chapter of Ueno Zoo’s history.

And the animals themselves? They were reduced to objects to be used for propaganda, especially directed at children. And their deaths continue to be used for propaganda aimed at children, this time for “peace”. Often depicted in harrowing detail, yet deeply sentimentalized, their story is meant to show how horrible war can be (e.g., Tsuchiya & Takebe, 2009).

The new memorial (erected in 1975) for animals that died in Ueno Zoo

Fukuda Saburō is portrayed as he wanted to see himself: a man distraught with grief about being forced by orders and circumstances beyond his control to manage the slaughter in this particular way (e.g., Kōno & Terada, 2007; Ueno, 1982a, 182). After all, such were the times, as his successor Komori Atsushi claims (Tanabe & Kaji, 1982, 35). Yet, there had been alternatives, and the animals died an unnecessary, and often unnecessarily cruel, death. Until it is understood that the story of Ueno Zoo’s slaughtered animals illuminates less the nature of war, but rather some human beings’ moral failure, this will remain an instance of not coming to terms with the past.

Frederick S. Litten earned an M.A. in sinology and a Dr.rer.nat. in history of science, both from Ludwig-Maximilians-University, Munich/Germany. His current research interests cover anime and manga. He works at the Bavarian State Library as an expert on microfilmed archival documents and can be reached at [email protected]. His website is here.

Recommended citation: Frederick S. Litten, “Starving the Elephants: The Slaughter of Animals in Wartime Tokyo’s Ueno Zoo,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 38-3-09, September 21, 2009.

Reference List

Asakusa Hanayashiki (n.d.). In Wikipedia. Retrieved on September 3, 2009.

Barrington-Johnson, J. (2005). The Zoo. The story of London Zoo. London: Robert Hale.

Belfast zoo searching to identity[!]‚ ‘Elephant Angel’ (2009, March 23). Belfast Telegraph. Retrieved September 3, 2009.

Bleckman, M. (1992). Harry Piel. Ein Kino-Mythos und seine Zeit [Harry Piel. A cinema myth and his time]. Düsseldorf: Filminstitut der Landeshauptstadt Düsseldorf.

Chun, C. K. S. (2006). The Doolittle Raid 1942. America’s first strike back at Japan. Oxford : Osprey.

Denisenko, E. E. (2003). Ot zverincev k zooparky. Istoriya Leningradskogo zooparka [From menagerie to zoological garden. History of Leningrad Zoological Garden]. Sankt-Peterburg: Iskusstvo-SPB.

Earhart, D. C. (2008). Certain victory. Images of World War II in the Japanese media. Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe.

Fukuda, S. (1982). Jitsuroku Ueno Dōbutsuen [Chronicle of Ueno Zoo; originally published in 1968]. In Zenshū Nihon dōbutsu shi [Complete animal writings of Japan] (vol. 4, pp. 3-143). Tokyo: Kodansha.

Ganzenmüller, J. (2007). Das belagerte Leningrad 1941-1944. Die Stadt in den Strategien von Angreifern und Verteidigern [Leningrad under siege, 1941-1944. The city in the strategies of attackers and defenders] (2nd ed.). Paderborn: Schöningh.

Gordon, A. (2003). A modern history of Japan. From Tokugawa times to the present. New York: Oxford University Press.

Gottschlich, E. (2000). Wiedereröffnung und Zerstörung (1928-1945) [Re-opening and de-struction]. In M. Kamp & H. Zedelmaier (Eds.). Nilpferde an der Isar. Eine Geschichte des Tierparks Hellabrunn in München [Hippos by the Isar. A history of the Hellabrunn zoological garden in Munich] (pp. 112-138). München: Buchendorfer.

Hacker, H. (1940, October 13). Nummer 105: Harry Piel in Hellabrunn [Number 105: Harry Piel in Hellabrunn]. Völkischer Beobachter, p. 17.

Hasegawa, U. (2000). Zō mo kawaisō. Mōjū gyakusatsu shinwa hihan [The elephants are pitiful, too. A critique of the myths concerning the slaughter of wild beasts] (originally published in Kikan jidō bungaku hihan [Quarterly critique of children’s literature], nr. 1, September 1981]. In U. Hasegawa. Sensō jidō bungaku ha shinjitsu wo tsutaetekita ka [Has children’s literature on the war transmitted the truth?] (pp. 8-30). Tokyo: Nashinokisha.

Heck, L. (1952). Tiere – Mein Abenteuer. Erlebnisse in Wildnis und Zoo [Animals – My adventure. Experiences in wilderness and zoo.] Wien: Ullstein.

Johnston, W. (2005). Geisha, harlot, strangler, star. A woman, sex, and morality in modern Japan. New York: Columbia University Press.

Kawabata, A., & Vandergrift, K. E. (1998). History into myth. The anatomy of a picture book. Bookbird, 36 (2), 6-12.

Kawata, K. (2001a). Ueno Zoological Garden. In C. E. Bell (Ed.). Encyclopedia of the world’s zoos (vol. 3, pp. 1273-1276). Chicago, IL: Fitzroy Dearborn.

Kawata, K. (2001b). Zoological Gardens of Japan. In V. N. Kisling (Ed.). Zoo and aquarium history: ancient animal collections to zoological gardens (pp. 295-330). Boca Raton, FL: CRC.

Komori, A. (1997). Mō hitotsu no Ueno Dōbutsuen shi [Once more a history of Ueno Zoo]. Tokyo: Maruzen.

Kōno, K. (director), & Terada, T. (script) (2007). Zō no Hanako [The Elephants Hanako; TV drama]. Japan: Fuji TV, Kyōdō TV.

Maeda, Y. (director), & Saitō, H. (script) (1982). Zō no inai dōbutsuen [Zoo without elephants; animated movie]. Japan: Herald Entertainment, Group Tac.

Miller, I. (2005). Didactic nature: Exhibiting nation and empire at the Ueno Zoological Gardens. In G. M. Pflugfelder & B. L. Walker (Eds.). JAPANimals: History and culture in Japan’s animal life (pp. 273-313). Ann Arbor, MI: Center for Japanese Studies.

Miller, I. J. (2008, April). The Great Zoo Massacre: Odachi Shigeo and the logic of sacrifice in wartime Japan. Paper presented at the AAS Annual Meeting, Atlanta, GA. Abstract retrieved on September 3, 2009.

Refugees kill zoo animals (1923, September 5). The New York Times, p. 2.

Saotome, K. (1989). Sayōnara Kaba-kun [Farewell, Hippo]. Tokyo: Kinnohoshisha.

Senjijū no dōbutsuen – Mōjū shobun no shinjitsu wo motomete [Zoos during the war – Searching for the truth about the disposal of wild beasts] (n.d.). Retrieved on September 3, 2009.

Senjika no dōshokubutsuen [The zoological and botanical garden during the war] (n.d.). Retrieved on September 3, 2009.

Shōwa 20 nendai [The Shōwa 20s] (n.d.). Retrieved on September 3, 2009.

Tanabe, M. (text) & Kaji, A. (illustrations). Soshite Tonkī mo shinda [And then Tonkī also died]. Tokyo: Kokudosha.

Tetsudō shiryō Kenkyū-kai (Ed.) (2003). Zō ha kisha ni noreru ka [Can an elephant board a train?]. Tokyo: JTB.

Tōkyō-to Onshi Ueno Dōbutsuen (1982a). Ueno Dōbutsuen hyakunen shi [100 years history of Ueno Zoo]. Tokyo: Daiichi hōritsu shuppan.

Tōkyō-to Onshi Ueno Dōbutsuen (1982b). Ueno Dōbutsuen hyakunen shi – shiryōhen [100 years history of Ueno Zoo – materials]. Tokyo: Daiichi hōritsu shuppan.

Tsuchiya, Y. (text), & Takebe, M. (illustrations) (2009). Kawaisōna Zō [Pityful Elephants]. Tokyo: Kinnohoshisha. [Originally published in 1970.]

Ueno (1982a) s. Tōkyō-to Onshi Ueno Dōbutsuen (1982a).

Ueno (1982b) s. Tōkyō-to Onshi Ueni Dōbutsuen (1982b)

Zen mōjū kaeranu tabi he [All wild animals towards a journey of no return] (1943, September 5, evening edition). Mainichi shinbun, p. 2.

Zō no unmei [The elephants’ fate] (n.d.). Retrieved on September 3, 2009.

Zoo Frankfurt am Main – Die Jahre 1874-1945 [Zoo Frankfurt am Main – The years 1874-1945] (n.d.). Retrieved on September 3, 2009.

Notes

1 Poor Elephants, Tokyo: Kinnohoshisha, 1979; Faithful Elephants, ill. by Ted Lewin, Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin, 1988; Fidèles éléphants, ill. by Bruce Roberts, Montréal: Les 400 Coups, 2000. All these versions claim to tell a true story, although it has long been known–and was always evident– that at least one main contention was wrong: Tokyo was certainly not bombed daily in 1943; in fact, it wasn’t bombed at all in that year (cf. Hasegawa, 2000, 14-16; Kawabata & Vandergrift, 1998, 7).

2 Its history is extensively covered in Ueno (1982a).

3 This was certainly not the only instance of media reporting fiction about escaped animals. After the Great Kantō Earthquake in 1923, the New York Times wrote: “Men were shooting to death wild animals which had escaped from the Asakuska[!] zoo.” (“Refugees kill,” 1923, September 5). Asakusa, a Tokyo district quite near Ueno, had the oldest amusement park in Japan, the Hanayashiki, which also kept several animals such as tigers. Some animals there burned to death–fires broke out all over Tokyo after the earthquake–and others were poisoned to make place for refugees, but there is no report about any having escaped and been shot (Asakusa Hanayashiki, n.d.). At Ueno Zoo the animals were not physically harmed by the earthquake and did not escape either (Fukuda, 1982, 7-8).

4 In Munich’s Hellabrunn Zoo several large herbivores had been killed already in September 1939 to save on food, other animals were sold (Gottschlich, 2000, 132).

5 I will concentrate here on Ueno Zoo and on the details concerning the animals, leaving out aspects such as how to deal with visitors.

6 Tosei jūnen shi (quoted in Hasegawa, 2000, 21-22) also mentions discussions about the slaughter and the evacuation proposal; however, it is not clear whether they already began before, or only on August 16.

7 According to Fukuda’s official report (Ueno, 1982b, 739) and his memoirs (Fukuda, 1982, 101), this happened on August 20.

8 The python, the rattlesnake, two American bison, and the leopard cub had not been on the original list (Ueno, 1982a, 173-174; Ueno, 1982b, 738).

9 Starvation included withholding water from the animals.

10 This was not the first time John had not been fed because he was “wild” (Fukuda, 1982, 72). The picture book Soshite Tonkī mo shinda (And then, Tonkī also died), based on a TV documentary of the same title broadcast in 1982, claims that food scarcity was also cited as a reason in the official order (Tanabe & Kaji, 1982, 5).

11 On June 23, 1931, Fukuda (1982, 57) noted that John threw back potatoes that he found not sweet enough.

12 The elephants’ post-mortems were carried out within the zoo, as it would have been difficult to transport them secretly. While John was autopsied on August 30 in the elephant house, Hanako and Tonky were kept outside (Ueno, 1982a, 176). There seems to be no information on the whereabouts of Tonky during Hanako’s autopsy (Ueno, 1982a, 179-180). It is, however, unlikely that she was outside the elephant house because, officially, both elephants had already been dead for more than a week.

13 Before quoting from Fukuda’s diary, the 100 Years History of Ueno Zoo paraphrases his entry of September 14, but fails to mention the taking of a blood sample, and concludes with Fukuda’s assertion that there was no alternative but to starve Tonky (Ueno, 1982a, 180).

14 Tanabe and Kaji (1982), who took up Hasegawa Ushio’s critique of Kawaisōna Zō, give no reason at all why Hanako and Tonky had to be killed by starvation. Furthermore, only the potato and the poisoned water stories are mentioned, but nothing is said about any attempted injections.

15 The date of birth is based on the detailed description in Fukuda (1982, 65-66). Ueno (1982, 194) gives 1936. Saotome (1989) calls the young male Daitarō; according to “Senjijū no dōbutsuen” (n.d.) he was called Maru.

16 This is shown, e.g., in the anime movie Zō no inai dōbutsuen (Zoo without elephants; Maeda & Saitō, 1982).

17 An overview of “disposals of wild beasts” in Japan during the Second World War is given on the website “Senjijū no dōbutsuen” (n.d.).

18 The earlier Hanako had been written with the kanji “hana” (flower) and “ko” (child), whereas this Hanako was written with the hiragana syllables “ha” and “na” and the kanji “ko” (child).

19 The 100 Years History of Ueno Zoo hints at keepers refusing to get involved in the elephants’ disposal (Ueno, 1982a, 175).