Vivian Blaxell

I see the lines of imperial flags on the southern isle and think, oh how dazzling the Emperor’s reign!

I see the exotic stars of the Southern Cross in my window at dawn, but the rooster’s call sounds just the same

I see the strange sight of a soldier with a gibbon for a pet; yet in time regard it quite without suspicion.

Introduction

On the east coast of the Malay Peninsula between Mersing and Endau, a few kilometers in from the silvery beaches along the South China Sea, one comes to Kampong Hubong. It is still and hot here. Isolated. Rice fields lie fallow. Coconut palms, bougainvillea, hibiscus, and tall grasses tumble together in the fields. Small buildings of stucco and timber, gone grey with age and monsoon rains, line one side of a short paved street. A couple of Chinese men sit in the shade of the shophouses. They yak in the Hokkien dialect. A red dog yawns.

These days Kampong Hubong is a cul-de-sac on the map of Malaysian modernization. But once, for just two short years between 1943 and 1945, Kampong Hubong was closer to the core of things: a new community called New Syonan that emerged from the conditions of Japan’s occupation of Singapore, and acted as a highway for the delivery of imperial Japanese ideology about Asian unity and cooperation.

Japanese Singapore: The Conditions of Possibility

New Syonan came from a particular historical chronotope: the Japanese occupation of Singapore. British Malaya fell to the Imperial Japanese 25th Army on January 31, 1942. Pushed down the peninsula by a lightning quick Japanese force of about 60,000 men, many of them riding bicycles, the much larger British army, supplemented by “colonials,” dropped back in disarray on the great British redoubt of Singapore, second only to London in its importance to British global strategy. The Argyll regiment blew up the causeway connecting the island to the mainland as they went. But to little avail. On February 15, 1942, the British surrendered and Singapore became a part of Japan’s Greater East Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere, part of the Japanese Empire.

The Japanese military command and new civil authorities immediately set about turning Singapore into a Japanese imperial city, the capital of Japan’s empire in Southeast Asia [Nanpo], and they began by re-naming it, Syonan-to, Light of the South. Hotels were given Japanese names. The Raffles Library and Museum was renamed Syonan Hakubutsu-kan and headed first by the vulcanologist, Tanakadate Hidezo, and then by Tokugawa Yoshichika, an aristocrat, relative of the emperor, descendant of the last shogun. Mansions vacated by the British or made vacant by military evictions became homes for senior Japanese officers and civilian administrators. Churches became ammunition dumps. Commercial air service began between Fukuoka and Singapore via Hong Kong and Saigon.

In Japanese-era Korea, Taiwan and Manchuria, Japan radically transformed urban centers; redesigned and rebuilt them to represent the ideals at work in Japan’s modern visions of itself and its empire, or simply built new cities on Japanese imperial lines next to existing urban centers. But no grand designs for Singapore’s transformation existed or could have been implemented given the short time of Japan’s control of the city and significant problems with supply of labor and materiel for construction required to pursue the war effort. The most significant structures added to the city were religious. Except for some stones carved out to retain water for ritual hand washing, little remains today of the Syonan Jinja, a secluded Shinto shrine erected in tropical forest at MacRitchie Reservoir, but photographs from the time show a medium sized shrine with traditional Shinto buildings of unvarnished wood and thatch set in an expanse of white gravel next to one of the jungle waterways in the area.

Syonan Jinja was built largely by the labour of Allied prisoners of war: a cause for celebration in Japan of the “New Asia” liberated from European imperialism and the tables turned. The August 26, 1942 edition of the weekly photographic magazine, Shashin Shuho, sold at most Japanese news outlets and bookstores, has a cover photograph of a bare-chested POW wearing a “digger” hat, burnishing the brass fittings on a post of the Japanese-style arched bridge leading to the shrine grounds, and an inside photo spread of POWs toting construction materials and winching a torii gate into position, all accompanied by a brief but swaggeringly victorious text.

The Syonan Chureito, a shrine and memorial dedicated to the war dead on the summit of Bukit Batoh Hill, was a grander affair, memorializing the battle for Singapore. The ashes of Japanese troops killed in the campaign rested here beneath a 15-meter wooden cylinder topped in a rather phallic fashion by a brass cone.

Yet, if the urban space and landscape of Singapore did not change very much during Japanese rule, the culture and collective consciousness of the city did, re-forming in response to mundane changes, minor surprises and to unimaginable horrors. It was these changes that made the establishment of the new community, New Syonan, where Kampong Hubong now stands near Endau, possible. The city went onto Tokyo time. A new currency came into circulation, quickly becoming known as “banana money” because of the banana pictures on the notes. Japanese movies played in the cinemas. Radios broadcast the Japanese national anthem and news bulletins in Japanese. Newspapers that had reported the daily grind of King-Emperor George VI and his consort Elizabeth, now reported the Tokyo palace meetings and appointments of Emperor Showa, the Empress, and the Empress Dowager. A new form of popular entertainment emerged called getai, and Japanese soldiers urinated in the streets of the city; an unremarkable habit in Japan but uncouth for Singaporeans accustomed to British ways. Relaxed Japanese attitudes about public male nudity resulted in numerous incidents of Japanese soldiers stripping off and taking a bath beneath standpipes in the street, terrifying local Chinese women in particular who thought they were about to be raped.

British Singapore had been infamous for its sex trade; Japanese rule introduced new elements to the city’s existing business of servicing men’s sexual desire. The military authorities installed “comfort women” in requisitioned properties and turned them into “comfort stations” at Tanjong Katong Road, Wareham Road, Branksome Road, in the York Hotel, in the Anglo-Chinese School at Cairnhill Road, and in houses at Bukit Pasoh Road. Local Chinese women were the military’s first choice and comprised the majority of women forced into sexual servitude, but “comfort stations” in Singapore also included Korean and Indonesian women, as well as some Japanese women reserved for the officers. [2] Lines of Japanese soldiers waiting stolidly for their turn on the bodies of “comfort women” became a common sight. Enterprising local boys gathered up used condoms outside the comfort stations, washed them, put them in bamboo tubes, powdered them, rolled them up and resold them to Japanese soldiers.[3]

Approximately 3,000 Allied civilians were incarcerated under miserable conditions at Changi Prison, built by the British to house 600. The Japanese authorities imprisoned around 50,000 Allied soldiers at the Selarang Barracks near Changi.

Close to 850 died.[4] For the Chinese, Malay, Indian, and Eurasian people of Singapore, the time under Japanese rule was especially difficult, far more difficult than it was for Allied civilian internees and POWs. Looters and suspected looters were decapitated, their heads exhibited near the General Post Office at Fullerton Square and near the Cathay Cinema on Dhoby Ghaut.[5] Forgetting to bow to a Japanese soldier provoked verbal abuse at the very least and a beating at worst. Labourers, conscripted by force and transported from Java to work on Japanese projects in Singapore, were left to starve and die on the streets once their work was done or once they could work no more. “The plight of the Javanese destitutes,” wrote Lee Kip Lee in his diary of 1944,

is becoming worse. There are more of them straying in the streets, with ribs sticking out, hollow eyes, dirt crusted on their skins and nobody caring a damn for them. They are modern slaves, brought over here to toil and discarded when they are unfit. There are some of them gathered by Rochor Canal where, during the evenings, they group around a fire and cook their meal of odds and ends.[6]

And then there was the sook ching, a Hokkien term meaning “purge by cleansing” about which Geoffrey Gunn and others have written so acutely.[7] The sook ching was the greatest and most systematic of Japanese barbarisms in Singapore. Almost as soon as Singapore became Syonan, the military police and the 25th Army rounded up Chinese males, haphazardly interrogated them to determine if they were supporters of Chiang Kai-shek’s anti-Japanese government in China, members of triads, communists, and making decisions based upon the flimsiest of evidence — tattoos or literacy — transported them to the beaches at Changi, Punggol, or Sentosa, where now children swim and Singaporeans barbecue and spend the weekends in tents. There, the “undesirables” were shot, often as a group tied together with wire so that the dead dragged the still living down into the warm sea where they drowned. The sook ching continued in Singapore for some time after Japan took the city and re-occurred on October 10, 1943. Thousands were murdered, including women and children caught up in what the Japanese command called the Syonan Daikensho, the Great Singapore Inspection.

But, in Singapore, as in so many other parts of Japan’s empire, Japanese brutality coexisted with a different operation of power, one that aimed to be constructive rather than destructive in the effort to constitute the Japanese Empire, now reconceived by Tokyo as the Greater East Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere. This binary conduct of the Japanese imperial project bore similarities to European and American imperialisms in which violence and oppression often went hand in hand with pious constitutive practices. The mission civilisatrice of imperial France is a case in point. French imperial ideologues and colonizers paired subjugation with the burden of transforming colonized populations into “civilized” subjects through enlightenment projects.

For Japan, the civilizing mission emerged from its claim to be better able to deliver modernity to its subject peoples in Asia. There is not much of a departure from the European civilizing rhetoric in this. But where European colonial enlightenment discourse and practices were founded in, and reinforced, the otherness and difference of the imperial subject, Japan’s imperial rhetoric and constitutive practices in Asia were predicated on an intricate vision of difference and otherness within unity and sameness. Narratives about cultural, moral, and sometimes racial similarities between Japanese and other Asians consorted in Japan’s imperial discourses with critique of both Western imperialism in Asia and of Asian responses to it to produce an emancipatory project led by Japan for all Asians: Pan-Asianism or Asianism. The resultant complex interplay of Japanese ideology about Japanese superiority to other Asians and Japanese rhetoric about Asian unity and liberation from European imperialism produced idealistic Japanese cultural and economic experiments all over Southeast Asia during the period of Japanese rule.

The Asianist zeal of cabinet policy statements recommending cultural and economic development in service to the overarching goal of creating a cohesive and tight knit autarky in Asia patronized by Japan did not stay long in the rarefied atmosphere of Nagatacho,[8] and by the winter of 1942 hundreds of Japanese school teachers, some of them war widows, were leaving their homes in Kumamoto, Nagasaki, Tokyo, or Okayama to embark on voyages to Rangoon, Kuala Lumpur, Singapore, and Jakarta, there to improve the local education system and create good Japanese subjects in the far reaches of the empire.[9] Young Japanese men moved to Sumatra to train the locals in the techniques of nation construction, civic pride, and military organization. Japanese painters, musicians, writers, theatre and cinema directors [bunkajin] traveled to the Southern Regions both to represent the new parts of the empire to a domestic audience in Japan and to promote a Japanese inspired cultural renaissance.

The idea of Asian independence, renewal and cooperation put stars in the eyes of some Japanese. The projects they fostered in Southeast Asia bore the freight of their education and belief in pan-Asian principles, and the little Chinese village of Kampong Hubong, just a few kilometers south of Endau, a somnolent dead end now, was once a site for the working out of these Japanese ideas about Asian unity, cooperation and independence, for it was there that the new community of New Syonan was established for Singapore’s Chinese citizens. Fuji Village, a similar community for Singapore’s Eurasian community and Chinese Christians, was set up at Bahau in the hinterland of Negri Sembilan north of Melaka.

Neither New Syonan nor Fuji Village were exceptional in their time and place. Hara Fujio has identified over 30 new communities for Chinese scattered throughout the Malayan peninsula and the adjacent islands.[10] Marginalia and anecdotal traces in the historical records also suggest that the Japanese authorities in Singapore and Malaya set up new communities for Malays and at least one for Singapore’s Indians on Pulau Bintan, an island in the Riau group between Singapore and the coast of Sumatra. Hara argues that these new communities were products of Japan’s fear of Chinese anti-Japanese resistance and/or of the need to tackle widespread shortages of food, and the paucity of historical documents about the communities enumerated in Hara’s survey oblige us to accept this point. But New Syonan and Fuji Village are exceptional for the volume and quality of historical documents, both oral and textual, recording their founding and development. These documents permit us a nuanced account of New Syonan and Fuji Village, their histories, the discursive genealogy of their foundation, and their place in the simultaneously unifying and dividing practices of Japan’s Asianist visions and policies.

New Syonan and Fuji Village

Shinozaki Mamoru is a well-known character in the history of Japanese-era Singapore. He played a pivotal role in the establishment of the communities at Endau and Bahau. An enigmatic and somewhat unconventional figure, Shinozaki was the son of a coalmine owner from Fukuoka. Raised primarily by his devoutly Buddhist grandmother, as a youth Shinozaki mixed with prohibited left wing groups, and spent an atypical “bridge” year in unrecorded activities before studying journalism at Meiji Daigaku. Prior to the arrival of the 25th Army, Shinozaki worked in Singapore as a press attaché at the Consulate-General of Japan. In 1940, the British authorities charged him with three counts of espionage, convicted him on two and imprisoned him at Changi Gaol in November of that same year. Shinozaki always denied the charges, but British records examined by Brian Bridges suggest that Shinozaki was probably involved in advance guard Japanese intelligence operations in Singapore and Malaya in the years immediately before the outbreak of hostilities.[11] A significant number Japanese residents were. Liberated from prison by the 25th Army, Shinozaki immediately took a post as principal advisor to the military administration of the new colony, then as an education officer, before taking up the position as head of the city welfare department, Kosei-ka Cho.

Shinozaki was not one of those teachers, planners, military trainers, or agricultural specialists inspired by Asianist ideals to work on the Japanese emancipatory project in the Southern Regions. Indeed, there is no record of Shinozaki having ever been a member of an Asianist organization or clique in Japan, and he certainly had no stars in his eyes about the violent and oppressive activities of Japanese imperialism, having lived in Shanghai during the first half of the 1930s and witnessed the sook ching in Singapore. His postwar writings on the Japanese period in Singapore never question the “rightness” of Japanese imperialism in Southeast Asia. And, as we shall see, as an imperial bureaucrat, the language of his public and private communications to the people of Japanese-era Singapore is imbued with the figures, metaphors, tropes, and rubrics of Japanese Asianism. His policies and actions during the period comply with Asianist principles circulating in imperial theory and practice since the founding of the Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo in 1932.

Nevertheless, as a bureaucrat in the new regime, Shinozaki tried to serve both the agenda of the local Japanese military authorities and to shelter the Chinese and Eurasian communities from Japanese brutality. The Kosei-ka Cho handed out hundreds, perhaps thousands, of “good citizen” passes to Chinese and other Singaporeans in an attempt to protect them from sook ching roundups and other persecutions. Shinozaki acted as “point man” for the establishment of the Overseas Chinese Association (OCA) and the Eurasian Welfare Association, organizations he claims were designed to collaborate with Japanese policies and thereby ameliorate the treatment of Chinese and Eurasian Singaporeans.[12] And he was instrumental in the founding, development, and maintenance of the two new communities for Singaporeans at Endau and Bahau.

In August 1943 the city government, Syonanto Tokubetsu-shi, received a military directive from the 7th Area Army Headquarters. According to Shinozaki, the directive was a battle order of the highest priority couched in the most urgent of terms and requiring the evacuation of 300,000 people from the city, close to a third of the total population of Singapore at that time. Yet the directive left the mode of evacuation, the final destination, and the disposition of the evacuees unstated. The new mayor of Singapore, Naito Kanichi, sought a solution from the Kosei-ka Cho and from Shinozaki in particular. In his memoir, Shinozaki claims that the forced emigration of more than 100,000 Italians to new communities designed by General Badoglio in the Libyan desert during the late 1930s inspired him to devise a similar plan for Chinese Singaporeans, but the vision for New Syonan seems to have come from several figures in addition to Shinozaki, especially Dr. Yap Pheng Geck, a local Chinese businessman and officer of the Straits Settlement Volunteer Force.[13]

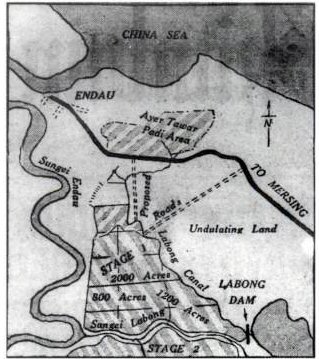

It was a team of Japanese and local Chinese, too, that went with Shinozaki to scout suitable sites for the new community in the state of Johor across the causeway from Singapore and finally found “this ideal valley not far from the sea amidst the Malay padi fields, very close to the sea where there’s good fishing” near the town of Endau, as one informant put it. The “ideal valley” belonged to Malays, but that presented no impediment to Shinozaki and his Chinese colleagues. It was swiftly expropriated as the site for New Syonan.

But it was the Japanese alone — Shinozaki, his team at the Kosei-ka Cho, and idealists at Army headquarters — who made New Syonan possible. These Japanese planners knew that something would have to be added to the plan for New Syonan in order for it to attract Chinese settlers from Singapore in any significant numbers. Good land, proximity to the sea, a guaranteed supply of rice, cash payments for the first six months, four acres of land for each settler, and materials for housing and agriculture would not be enough to draw Chinese Singaporeans out of the city. When asked why he had moved to New Syonan, Gay Wan Guay replied: “I wanted peace of mind.” And he went on to explain that like most Chinese men in Japanese-era Singapore, he was constantly afraid of making some inadvertent error, of unwittingly committing some crime, some discourtesy, that would result in his arrest and punishment by the Japanese authorities.[14] Shinozaki understood these fears. Working with the leaders of the Overseas Chinese Association he planned New Syonan as a community free of Japanese control and secured a promise from the army that the kempeitai would be kept away. The strategy worked. The first settlers made the 220-kilometer trek to New Syonan in September, 1943.

The city government orchestrated a public relations campaign to encourage emigration. Front-page articles lauding New Syonan and foregrounding its freedom from Japanese control began appearing in the local newspapers. In December, 1943, Mrs. Chu Chi Kit returned from a visit to New Syonan and in an interview described the community as “a grand place” and a “big attraction to housewives as the cost of living is low, and the healthy and bracing climate assures them that they will have no worries with regard to sickness or ill-health.” A few weeks later, reports about the establishment of a New Syonan banking agency controlled by the Overseas Chinese Association underscored the independence of the community: “— this step will appeal to the settlers as they, the principal patrons, will thus be able to appreciate that the agency belongs to them and is being run for their sole benefit.” And in the middle of March, 1944, Singaporeans learned that “One of the most popular dance hostesses in Syonan, Miss Chan Pui King, better known as Pak Sim, is now cultivating her own plot of land in New Syonan.”[15] New Syonan was reported to be safer and better supplied with food than Singapore. People moved. One year after the founding of the new community the population had reached 12,000. Convoys of settlers left Singapore for New Syonan regularly and

–every time a convoy went up, it was full to the brim. We had to hang our bicycles outside, by the side of the lorry. I remember I had my bicycle wheel ripped off, and a total loss of a bicycle for nothing. And no place inside the lorry for it. And I was perched right on top. I don’t know how I survived.[16]

Life at New Syonan seemed to flourish. The initial dwellings were rough, made out of tough, brown opeh leaves, but by March 1944, inhabitants could live in long barrack style houses with thatched roofs and timber walls set out in a Malay-style lorong pattern of narrow dirt lanes on a neat grid. Every family at New Syonan had two rooms in a barrack, each about 1.2 square meters in area, along with access to a shared kitchen, bathroom, lavatory, verandah, and backyard for raising chickens and ducks. The new banking agency turned into a branch of the Overseas Chinese Banking Company [OCBC]. A school opened for the children. A pasar malam [night market] opened. There were coffee shops, a small stage for performances of both Chinese and western music, and a legendary Chinese restaurant in Singapore, “Wing Choon Yuen,” established a branch at New Syonan. “My mother went [to New Syonan] with some of her relatives. And also they were quite happy over there. They have a lot of food, fishes [sic], everything” remembers Robert Chong.[17]

Though New Syonan may have been an improvement on Singapore, it was no arcadia. Japanese support for the community did not run to money. Shinozaki charged the Overseas Chinese Association with fiscal responsibility for the cost of setting up and developing the place, but funds were hard to find since the Chinese in Singapore had forked over a $50 million cash payment to the Japanese authorities in 1942 as an “apology” for its anti-Japanese activities. The labour of building and then maintaining the community was even harder than finding the funds to pay for it. Roads in from the Endau to Mersing highway had to be built by hand through thick vegetation. Land had to be cleared for cultivation. The work of clearing jungle, plowing land, seeding it, irrigating, raising crops, harvesting, building barracks, schools, and other structures was very hard for many of the city dwellers.

Tan Kim Ock recalls being close to tears when confronted with his new parcel of land at New Syonan: “The plot was a wood. The trees had all been chopped down and were lying in a messy heap — The trees were tall and huge and the heap was about two storeys high.”[18] Richer immigrants attempted to replicate the class relations of Singapore and hire wage labourers to do the heavy work while they sat around drinking tea and playing mahjong. But the business of raising enough food to feed a population that grew to more than 12,000 by September 1944 was too demanding to permit a leisure class, and the dissonant sight of permed and made-up city women working the fields like peasants was not at all unusual.[19] Though the feared kempeitai kept away from New Syonan as promised, the atmosphere could still be tense: many settlers suspected informers among them and feared Shinozaki’s visits; members of the Japanese garrison at Mersing took to dropping by and demanding the best of the fishing catch for themselves. Disease does not appear to have been a problem, but attacks by resistance guerillas of the Malayan Peoples’ Anti-Japanese Army (MPAJA) were. The MPAJA regarded New Syonan as a community of collaborators. In 1944 the guerillas mounted a number of attacks on New Syonan. Several leaders of the community and of the Overseas Chinese Association were wounded and some were killed, including Wong Tat Seng, chief of New Syonan security. The MPAJA also assassinated Wong’s successor, Lo Po Yee. Settlers began to request return to Singapore, but the attacks ceased when Shinozaki promised to supply rice to the MPAJA in return for an agreement to leave the settlement alone. [20]

News of the success of the New Syonan community prompted the head of the Catholic community in Singapore, Bishop Adrian Devals, to approach Shinozaki about setting up a similar community for Eurasians. The Japanese authorities governing the Malay state of Negri Sembilan already had plans for a huge resettlement scheme designed to address problems in the food supply, and it offered land to the Eurasians and Chinese Catholics of Singapore very near Bahau, a small Malay town in the foothills between Melaka and Port Dickson on the west coast of the peninsula. Shinozaki recalls having serious reservations. The soil at Bahau was mostly clay and unsuitable for effective agriculture. The water supply was insufficient to sustain a sizeable population. More importantly, the Japanese authorities in Negri Sembilan refused to allow the Fuji Village community to govern itself. But the plan went ahead over Shinozaki’s concerns. The government embarked on another public relations campaign and glowing reports about life for Eurasians at Fuji Village appeared in the daily newspapers quoting anonymous sources: “I am delighted with Bahau,” said one, while according to the Syonan Shimbun another settler flexed his biceps and said, “During the first week, we found the work pretty hard but now we are accustomed to it and are getting our muscles too.”[21] The truth was, however, that the new community at Bahau was an unmitigated and prolonged disaster.

Part of the problem for the settlers at Fuji Village seems to have been their sense of priorities: one of their first projects was erection of a church and altar. In the oral testimonies held at the National Archives of Singapore, former residents of the Chinese community at New Syonan tend to explain the failure of Fuji Village in ethnic and cultural terms, suggesting that the Chinese at New Syonan were naturally imbued with the pioneering spirit of their forefathers who came from China to Southeast Asia with nothing, and thus better able to build a community from scratch, whereas in these accounts the Eurasians at Fuji Village were innately dependent and too long accustomed to easy living for the endeavour to succeed. But what definitely defeated the people of Fuji Village was the challenge of unaccustomed manual labour and ignorance of agricultural techniques. As well, the project was under-funded.

The Japanese authorities in Negri Sembilan refused to supply rice or vegetable seedlings. And the land upon which the new village was situated turned out to be a breeding ground for malarial mosquitoes, fierce swarms of insects that had already seen off a group of Japanese soldiers trying to build an airfield there. Malaria and other insect borne diseases killed many. Malnutrition killed some. Even Bishop Devals, the founder of Fuji Village, gave his life to the project, dying of tetanus in 1945 after accidentally lacerating his foot with an agricultural hoe. Between the autumn of 1943 and the Japan’s surrender in September, 1945, at least 300 and perhaps as many as 1,500 settlers at Fuji Village died. At war’s end, while some Chinese chose to stay on in New Syonan, the surviving people of Fuji Village took the first train back to Singapore, a testament to the relative success of one and the failure of another.

Asianism and New Syonan

The strategic aim of Japanese plans for new agricultural communities in Malaya was to alleviate severe food shortages. In this, both New Syonan and Fuji Village failed. The populations of the two communities never approached the numbers specified in Japanese plans, and the food produced in both was never enough to make either community self-sufficient. But Shinozaki’s support for New Syonan in particular never wavered, and we must ask ourselves why? In his memoirs Shinozaki represents his decision to implement New Syonan in uncomplicated humanitarian terms, and his conduct in Japanese-era Singapore is often seen in those same terms today.[22] But this is too simple. Shinozaki and the Kosei-ka Cho staff worked in the ambivalent yet pivotal space between the two core projects of Japanese imperialism: violent subjugation and strategic necessities on the one hand, pan-Asianist unity, cooperation and emancipation on the other. For example, Shinozaki’s issue of “good citizen” passes to Chinese rounded up during the sook ching was sometimes open-handed and unconditional. On other occasions, however, he linked issue of a pass to cooperation with Japanese policies and needs. When the sook ching roundup caught Chinese community leader, Lim Boon Keng, in its net in March 1942, Shinozaki offered him a pass on the condition that he head the establishment of the Overseas Chinese Association.

In his memoirs, Shinozaki insists the OCA was designed only to protect the Chinese community, and the OCA is often remembered as an agent of protection in the oral testimonies about the period. Yet, the OCA created by Shinozaki to protect Singapore’s Chinese community was also used to extort $50 million from local Chinese as an “apologia” for anti-Japanese activities. Similarly, Shinozaki’s enthusiasm and support for New Syonan and Fuji Village was about something other than straightforward humanitarianism. The problems of food supply in Singapore were critical; the need to reduce the city population drastically was imperative. Singapore’s population had ballooned in the weeks prior to Japanese conquest and did not decline after Japanese occupation began. The war in China dragged on, while the southern front extended to New Guinea and New Britain just north and east of Australia. American naval power in the Pacific recovered more quickly than Japanese planners had foreseen, and Japan’s supply lines soon began to shred. By the middle of 1943, Japan was having trouble feeding its troops let alone a city of approximately 1 million. Solutions to the provisioning of civilians in Singapore had to be found. The evacuation directive from the 7th Area Army headquarters could have been implemented in other and more effective ways. The option of transporting vast numbers of Singaporeans to anywhere in the empire and simply dumping them, or transporting them to work in Japanese mines or on Japanese construction sites, such as the notorious Burma Railroad, was open to the Tokubetsu-shi and had precedent. But Shinozaki and his staff at the Kosei-ka Cho chose another way to invest in the imperial project. They chose to invest in the constitutive, emancipatory part of Japan’s project in Southeast Asia.

We can detect the discursive capital funding Shinozaki’s investment in his own account of why he acted as he did in Singapore. During the negotiations about the establishment of the Overseas Chinese Association, Lim Boon Keng queried his motivation. Shinozaki replied:

I have many friends in China. I have lived in China for four years. I respect Chinese culture — the Chinese are Japan’s old teachers. We have learnt many things from China’s past. My name means “Cape of China”. Sino means China and Zaki means Cape. And my first name is Mamoru, which means to protect.[23]

Here in the manipulation of friendship, the past and the symbolism of names we find traces of the Japanese Asianist unifying assumption and a logic for the founding of New Syonan. Kita Ikki, the ultranationalist and pan-Asianist executed for his complicity in the abortive officer’s coup of February 26, 1936, justified Japanese colonialism in Korea in terms of shared history, shared cultural patterns, and shared blood. Later, colonial theorists and political front men expanded Kita Ikki’s construal of the Japanese imperial relationship with Korea to account for Tokyo’s takeover of Manchuria after 1931: shared geography, history, culture, and blood. When the Kwantung Army invaded China in July, 1937 and Tokyo announced its New Order in East Asia in 1938, Japanese imperial theorists and policy makers, such as public intellectual Miki Kiyoshi and Foreign Minister Matsuoka Yosuke, to name just two, had already decided that China was not a nation state, but a civilization tied to Japan by history, culture, and faint tracings of descent – a common culture and a common race — thereby domesticating the wild problem of Japan’s invasion of a sovereign state. By the time of the establishment of the Greater East Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere in Southeast Asia in 1942, this unifying theme was an old story, doxological, and it should not be surprising to find its marks in the activities in Singapore of Shinozaki Mamoru.

The logic of Shinozaki’s policies in Singapore also enacted imperial benevolence, a central principle of Japanese colonial theory in the late 1930s, drawn from concepts of Japanese imperial rule found in the 8th century Kojiki refurbished as a part of Japan’s East Asia vision, and encoded in the January 1941 Field Service Code: “Imperial benevolence is extended to all without favour, while the Imperial virtues enlighten the world.”[24] Japanese benevolence was, however, contingent upon cooperation. It was an act of power: a Japanese sort of noblesse oblige. Protection is benevolence administered by the powerful on the part of the powerless. The protection represented by Shinozaki’s given name “Mamoru” functions to naturalize the power relations contained in the imperial code of benevolence. It elides the taint of strong and weak which is itself the mechanism upon which the Japanese assumption of superiority and leadership in Asia, emerging from Japanese reworking of Social Darwinism, was grounded. Shinozaki’s assumption is in error. His specific error is also the general error of this sort of Japanese Asianist discourse: benevolence encoded as protection cannot successfully elide nor pacify the power-laden operations of self and other in Japanese-Asian relations: in this case, Japanese brutality in Singapore. Nonetheless, in the end, in Shinozaki’s account, culture, history and geographical proximity unite Chinese and Japanese, while benevolence as protection provides a sort of Confucian morality for it all, and it is this mix of the unifying move with imperial benevolence that made New Syonan epistemologically possible.

The operations of Asianist discourse and rhetoric within Shinozaki’s thinking had policy impact. In his framing of the foundation of New Syonan and Fuji Village, Shinozaki dissected Singapore into ethno-cultural communities for resettlement in Malaya: Chinese to New Syonan; Eurasians and Chinese Catholics to Fuji Village where the two groups lived in separate communities. In this dissection based on ethnicity and culture, the establishment of New Syonan and Fuji Village complied with an existing imperial model for management of plurality within unity.

Prior to World War 1 the unifying principles of Japanese imperialism and colonialism held sway. Despite discussions about Japanese superiority and the ineluctable difference of others, Japan’s first colonies, Hokkaido and Okinawa, became almost instantly unified with the Japanese state in 1869 and 1879 respectively. In 1911 Tokyo annexed Korea and turned all Koreans into Japanese subjects/citizens, no matter their actual place of residence. Taiwan (1895) and Japan’s Micronesian island territories (1920 as a League of Nations mandate) remained as distinct colonial political units but were both at somewhat different points on a trajectory toward the same place: toward becoming Japanese, toward unity. But empire by annexation and assimilation became more difficult for Japan after World War I.[25] The Wilsonian vision of self-determining nation-states first formally mooted in a presidential address to the United States Congress in January 1918 now put 19th century modes of empire building under serious question.

Japanese discourses of Asian unification remained in circulation, but by the 1930s Japan’s Greater East Asia rhetoric called for a different sort of empire: a regional and independent union or consortium of ethnic nations; a league of differences looking upward to Tokyo but liberated from the western yoke to develop their own abilities, while always progressing in accord with the needs of the imperial center. Foreign Minister Matsuoka Yosuke’s 1940 vision of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere called for coexistence and co-prosperity [kyozonkyoei] among the ethnically defined nations of the sphere under conditions determined and imposed by Japan as the senior and “better” member of a unified autarky characterized by internal differences. In a Wilsonian move, Matsuoka also emphasized the right of all peoples within the autarky to freedom of action, describing opposition to it as unnatural [fushizen].[26]

The first and most notable application of this vision of an empire of self-determining, ethnic states in a Japanese-led regional consortium came with the establishment of the Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo in 1932. But in the formation of Manchukuo Japan encountered an additional layer of diversity that needed an Asianist resolution, and it is this sort of resolution that Shinozaki brought to bear on the foundation of New Syonan and Fuji Village, for Shinozaki was an imperial bureaucrat, and as Kevin Doak notes, the theoretical discourse on ethnic nationalism had deeply influenced “sectors of the imperial Japanese bureaucracy.”[27] Like Singapore in 1943, Manchuria was populated by diverse ethno-cultural groups. Not only did the puppet state have to have its own identity and its own freedom of action within the confines of the regional consortium, a domestic order that took internal diversity into account was also required. The solution in Manchuria was to use ethnography, psychology, history and racial science to define a set of internal ethnic nations, to assign each domestic nation an identity and a role in the puppet state and to construct a net of discourse within which each ethnic nation could understand itself, its entitlements and duties. Ignoring and excluding Russians, Germans, Jews, Ukrainians, Poles, Tartars, and other groups, Japan defined five ethnic nations within the territory that would soon become Manchukuo: Chinese, Manchus, Mongols, Koreans, and Japanese. [28]

The rubric of gozoku kyowa [harmony of five ethnicities] was used to explain and guide management of Manchukuo’s domestic diversity. It is generally considered that gozoku kyowa originated in the deliberations of the young Japanese living in Manchuria who formed the Youth Association of Manchuria in 1928, but they did not cut the concept from whole cloth, for gozoku kyowa drew on and responded to Sun Yat-sen’s unifying nationalist principle for Republican China, also pronounced gozoku kyowa in Japanese, but using different characters for kyowa and meaning something like “the republic of five ethnicities.”[29] In application, ethnic categorization, gozoku kyowa, self-determination and ethnic nationalism came together in Manchukuo to underpin the formation of ethnically delimited communities charged with specific roles in the project of Japanese imperialism. And it is here that the genealogy of New Syonan and Fuji Village begins, for the communities in Malaya and the communities in Manchuria shared several characteristics. In Manchuria, Manchu and Mongol lands were expropriated to provide land for self-sufficient agrarian communities for Japanese or for Koreans; in Malaya, Malay lands were expropriated to provide lands for self-sufficient agrarian communities for Chinese or Eurasians or Chinese Catholics. The communities in both Manchukuo and in Malaya were exclusive to their ethnic constituencies. And both sets of communities were explicitly charged with facilitating Japan’s imperial project, and both were implicitly charged with demonstrating the logic of Japan’s Asianist visions.

New Syonan provided a Southeast Asian demonstration of the workability of ethnic diversity within regional unity. It was ethnic [Chinese], independent [self-governing] and cooperative [contributing to the wider goals of Japan’s imperial imagination] and integrated into the vertical structure of the Co-Prosperity Sphere model [ultimately answerable to Japan and owing its very existence to the needs of Tokyo]. The plan for New Syonan as an independent community for Chinese established under the Japanese leadership of Shinozaki and his staff was thus a moment of Asianist praxis. As such, New Syonan possessed considerable rhetorical value, and Shinozaki understood that value very well: in a speech given at New Syonan and reported in the Syonan Shimbun of January 7, 1944, Shinozaki declared that the community would stand as “a permanent landmark” to “Chinese goodwill and cooperation” not just in Malaya, but throughout Asia and the world. As such, New Syonan would also stand as an empirical example of Japan’s new order in Asia.

Shinozaki and his Kosei-ka Cho staff do not seem to have felt quite the same Asianist enthusiasm about the Eurasian settlement at Bahau, Fuji Village. Perhaps the mixed genetic ancestry and heterogeneous cultures of Eurasians presented epistemic challenges to Asianist ideology about ethnic nations. Perhaps too, the refusal of the Japanese authorities in Negri Sembilan to permit Fuji Village the required Asianist measure of self-determination made it harder for Shinozaki to sing its praises. But, whatever the foundations of his disappointment in Fuji Village may have been, Shinozaki continued to practice imperial benevolence until the end of the war, secretly sending supplies of rice and other materiel to the struggling community. For like many of the pan-Asianist idealists in Japanese-era Southeast Asia, Shinozaki was not much deterred by the signs of Japanese brutality and indifference all around him. Setbacks to his personal pan-Asian agenda and the conclusive failure of Japan’s great pan-Asian enterprise did little to disillusion him it seems.

Just days after Emperor Showa announced Japan’s surrender to the Allied powers on August 15, 1945, Shinozaki wrote two letters to the people of New Syonan, now held in the National Archives of Singapore. Though his letters have an elegiac tone, both the egalitarian spirit and the inequitable power relation of Japanese pan-Asianism still circulate in them, not much abated. In the first letter Shinozaki articulates the idealistic Asianist vision of regionalism, independence, and development: “New Syonan still belongs to the Chinese people.” Shinozaki writes before exhorting the community to “please carry on your good work in New Syonan and make it a permanent success.” But later that same day [August 18, 1945] Army headquarters called him in and attacked him for informing the people of New Syonan and Singapore about the end of the war without permission from the military command. Threats were made against his life. Perhaps this experience accounts for the changed tone of Shinozaki’s second letter to New Syonan, written on August 19. In it he recovers the vertical structure of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, enjoining the people of New Syonan to obey their leaders and accept the protection of the “Nippon Military” “until the last moment” before expressing the hope that they will “always bear in mind the Dai Toa spirit” by which he means of course, the simultaneous independence and cooperative obedience required of all units in the Co-Prosperity Sphere.[30]

Concluding Remarks

In the current discursive welter of public and academic histories, personal testaments, foreign policy scandals, and media exposés about the character of Japan’s rule in Asia, most of it concerned with Japanese war crimes, oppressions, exploitation and crises of Japanese historical consciousness, it comes as some relief to discover New Syonan and Fuji Village, and the testament they bear to the other Japanese way of doing empire. This is not to suggest that the constitutive and optimistic planning behind the new communities in Malaya were any less about imperial control than slave labour and mass killings. But the story of Singapore, Shinozaki Mamoru, and New Syonan does point us toward recognition of certain emancipatory possibilities inherent in Japan’s imperial project. Asianist and Pan-Asianist discourses in Japan were not only rhetorical subterfuges for a real Japanese imperial agenda. They were a new way of “doing” imperialism; a way that existed alongside subjugation and exploitation, indeed consorted with them at times, and found expression in the establishment and development of new communities like New Syonan.

Notes

[1] Translated from a high resolution JPEG of Tanaka Katsumi, Minami no hoshi [Southern Stars] and an HTML version of the same text at Accessed October 22, 2007.

Poetic Japanese is not one of my strengths and I would like to thank Professor Muta Orie, Himeji Dokkyo Daigaku, for her invaluable help with the translation. Of course, all infelicities of translation and poetic expression are my own.

[2] National Archives of Singapore, Oral History Project, Japanese Occupation of Singapore, Robert Chong OHC000273, and Raymon Thien Hui Huang OHC002164. Also Hayashi Hirofumi, Maree hanto ni okeru nihongun ianjo ni tsuite [Japanese Military Brothels in the Malay Peninsula] Shizen – Ningen – Shakai, No 15, Kanto Gakuin University Department of Economics, 1993.

[3] Lee Geok Boi, The Syonan years: Singapore Under Japanese Rule 1942-1945. Singapore: National Archives of Singapore, 2005, p. 201.

[4] The number of Allied POWs who died in Japanese camps in Singapore is quite low compared to mortality figures in camps in other parts of the region. Changi, as the Singapore POW camps became known, has become synonymous with Japanese atrocities against POWs in late 20th century historical consciousness, but the historical record tells a rather different story. See, for example the Australian War Memorial encyclopedia.

[5] National Archives of Singapore, Oral History Project, Japanese Occupation of Singapore, Taman bin Haji Sanusi OHC000195; Ong Chye Hock OHC000168.

[6] National Archives of Singapore, Private Records, Accession No. 57, Microfilm No. NA1124.

[7] See Geoffrey C. Gunn, “Remembering the Southeast Asian Chinese Massacres of 1941-1945.” Journal of Contemporary Asia, Vol. 37, No. 3, pp. 273-276.

For Japanese accounts of the sook ching in Singapore see, for example, Takashima Nobuyoshi, Nihon no Haisen to Higashi Ajia (Japan’s Defeat and East Asia), Vol. 11 in Dainiji Sekai Daisen (The Second World War), Tokyo: Taihei Shuppansha, 1985, pp. 64-72.

[8] For such policy recommendations, see for example, Daitoa kyoeiken kensetsu ni tomofu bunkateki jiko ni seki shi joshin no ken [Recommendations on cultural matters in conjunction with building of Greater East Asia Co-prosperity Sphere], Imperial Rule Assistance Association, Cabinet No.3 Investigation Committee, 26 September, 1941. Japan Center for Asian Historical Records, National Archives of Japan, Reference code: A04018583900. www.jacar.go.jp Accessed October 8, 2007.

[9] Syonan Shimbun, 23/2/1943.

[10] Hara Fujio, “The Japanese Occupation of Malaya and the Chinese Community” cited in Paul Kratoska, The Japanese Occupation of Malaya: A Social and Economic History. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. 1997, p. 277.

[11] Brian Bridges, “Britain and Japanese Espionage in Pre-War Malaya: The Shinozaki Case.” Journal of Contemporary History, Vol.21, No. 1, pp. 23-35.

[12] For details of Shinozaki’s activities in Singapore see both the Japanese version Shingaporu senryohiroku – senso to ningenzo. [A Memoir of the Occupation of Singapore – The Human Face of War.] Tokyo: Hara Shobo, 1976, and the somewhat redacted English translation of his memoir about Japanese-era Singapore, Syonan – My Story: The Japanese Occupation of Singapore, Singapore: Marshall Cavendish, 2006. See also numerous oral accounts by Singaporeans held in the Oral History Project, Japanese Occupation of Singapore, National Archives of Singapore.

[13] National Archives of Singapore, Oral History Project, Japanese Occupation of Singapore, Robert Chong OHC000273.

[14] National Archives of Singapore, Oral History Project, Japanese Occupation of Singapore, Gay Wan Guay OHC000374.

[15] Syonan Shimbun, 22/12/1943; 31/12/1943; 16/03/1944.

[16] National Archives of Singapore, Oral History Project, Japanese Occupation of Singapore, Gay Wan Guay OHC000374.

[17] Robert Chong, op.cit.

[18] Quoted in Paul Kratoska, op.cit, p. 279.

[19] See relevant sections on New Syonan in Yap Pheng Geck, Scholar, Banker, Gentleman Soldier: The reminiscences of Dr. Yap Pheng Geck, Singapore: Times International, 1982. Yap’s memoir should be approached with caution since a cloud of “collaborator” hung over him after Japan’s surrender, as it did over many of the OCA leaders. However, unlike some of Yap’s memories of New Syonan, his image of rich Chinese working the fields at New Syonan is consistent with many of the oral testimonies about the community held in the Singapore National Archives.

[20] Shinozaki Mamoru, Shingaporu senryohiroku – senso to ningenzo. [A Memoir of the Occupation of Singapore – The Human Face of War.] Tokyo: Hara Shobo, 1976, pp. 50-55. And corroborated in many of the oral testimonies about the community held in the Singapore National Archives.

[21] Syonan Shimbun, 11/01/1944; 20/01/1944.

[22] For examples of this popular and uncomplicated interpretation of Shinozaki’s actions in occupied Singapore see, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shinozaki_Mamoru and also ourstory.asia1.com.sg/neatstuff/tanss/ssjap.html

[23] Shinozaki Mamoru, Syonan — My Story: The Japanese Occupation of Singapore. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish, 2006, p. 33.

[24] Tokyo Gazette Vol. 4., No.9, January 8, 1941, pp. 343-346. Accessed October 18, 2007.

[25] Dick Stegewerns puts the change at 1910 in “The Japanese ‘Civilization Critics’ and the National Identity of Their Asian Neighbours, 1918-1932: The Case of Yoshino Sakuzo” Li Narangoa and R. B. Cribb, eds. Imperial Japan and National Identities in Asia, 1895-1945. London: Routledge, 2003, pp. 107-128.

[26] Toa shinchitsujo kensetsu to zaishi beikoku ken’eki 3 [Establishing the New Order in East Asia, and US interests in China, 3, Record of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 1940. Japan Center for Asian Historical Records, National Archives of Japan, Reference code: B02030598400. www.jacar.go.jp/ Accessed November 18, 2007.

[27] Kevin M. Doak, “The concept of ethnic nationality and its role in Pan-Asianism in imperial Japan.” Sven Saaler and J.Victor Koschmann, eds. Pan-Asianism in Modern Japanese History: Colonialism, regionalism and borders. Asia’s Transformations Series, New York and Abingdon: Routledge, 2007.

[28] Mariko Asano Tamanoi, “Knowledge, Power, and Racial Classification: The ‘Japanese’ in ‘Manchuria.’” The Journal of Asian Studies, Vol. 59, No. 2, May 2000, pp. 249-250.

[29] Yamamuro Shin’ichi, “Manshukoku” no nori to seiji – josetsu” [“The principles and politics of “Manchukuo” – An Introduction], Jinbungakuho (Humanities Bulletin), Kyoto University, Vol. 68, March 1991, pp. 136-137. Accessed December 9, 2007.

[30] Letters from Shinozaki Mamoru to the people of New Syonan. National Archives of Singapore.

Vivian Blaxell is Associate Professor at Fatih University in Istanbul. She may be contacted at [email protected]

She wrote this article for Japan Focus. Posted on January 23, 2008.