Which Side Are You On?: Hakenmura and the Working Poor as a Tipping Point in Japanese Labor Politics

Toru Shinoda

This article analyzes one of Japan’s most widely reported labor stories in recent years. The unusual degree of national attention given to this incident is evidence that the labor question has become a central issue in Japanese politics.1 It also offers insight into critical shifts in the landscape of both labor politics and labor policy, which have implications for Japanese politics more generally.

Toshikoshi Hakenmura: A Japanese “Hooverville”

In Japan, the week or so from the end of December through the first days of the New Year constitute the longest and most solemn holiday of the year. Mainstream newspapers and TV news programs during this week are typically filled with mundane reports of the events of the season. But the week bridging 2008 to 2009 was distinctively different. Each day, the newspapers, TV news programs, and even websites such as Yahoo carried reports—often as the top story with frequent updates—of a unique camp supplying food, beds, health checks, and even spiritual support to jobless and homeless people gathered in the center of downtown Tokyo. This news drew an unexpectedly wide range of attention and generated unprecedented reactions, and its drama symbolized the recent suffering of Japanese workers and their families, especially “the working poor.” The entire episode suggests there has been a turning of the tide in Japanese labor politics.

Hakenmura residents march to the Diet on January 5, 2009 demanding food, housing and jobs

The name of the camp is Toshikoshi Hakenmura, roughly translatable as “New Year’s Eve Village for Dispatched Workers (the full term for “dispatched worker is “Haken Rōdōsha”). In recent years, Japanese employment agencies have been dispatching thousands of workers on short-term or temporary contracts to manufacturing companies such as automakers. But in late 2008, many of these contracts were suddenly canceled as manufacturers responded to the recession by reducing production (these cancellations are termed “haken-giri” or “dispatch cuts.”). During the period of their contract, these workers had typically been housed in dormitories for temporary employees. As their contracts were cancelled, the workers were ordered to leave the dormitory. In the current economic climate, the dispatching agency was hardly able to provide new jobs to these unemployed workers. Many soon found themselves indigent, and some were homeless, compelled to sleep on park benches in the cold night. Very few homeless shelters are available in Japan in any case, and because relevant public offices are closed, the holiday season is the hardest time for these homeless. This was the context for the opening of the Toshikoshi Hakenmura.

The idea for this village emerged from a discussion in December 2008 at a bar in Tokyo among activists and lawyers who had been helping unemployed dispatch workers. These activists organized an executive committee to prepare the village, which opened at Hibiya Park, Tokyo’s relatively small “Central Park,” over the week from December 31st to January 5th (at which date public offices for the unemployed were supposed to open). The organizers distributed food and lodging, provided counseling and employment consulting services, and helped the residents apply for welfare benefits. The residents pitched tents for their lodgings, but the space was cramped and it was hard to sleep with nighttime temperatures around the freezing point.

On January 2nd, the executive committee requested the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare (MHLW) to open its building located opposite the park. The Ministry promptly agreed and provided its main hall to lodge these homeless individuals. During these 6 days, more than 500 unemployed and homeless workers stayed at the village, and nearly 1700 volunteers worked there. Donations to the village totaled 23,150,000 Yen (about $230,000). After January 5th, the MHLW worked together with the Tokyo Metropolitan authorities to open temporary shelters for those workers who still needed accommodations. Not a few of the workers who came to Hakenmura spoke of killing themselves if they could not find some hope, and indeed, Japan has recorded more than 30,000 suicides every year since the mid 1990s. This compares to a steady annual rate of roughly 20,000 suicides over the previous two decades, and as a per capita ratio is double the current levels in the United States.

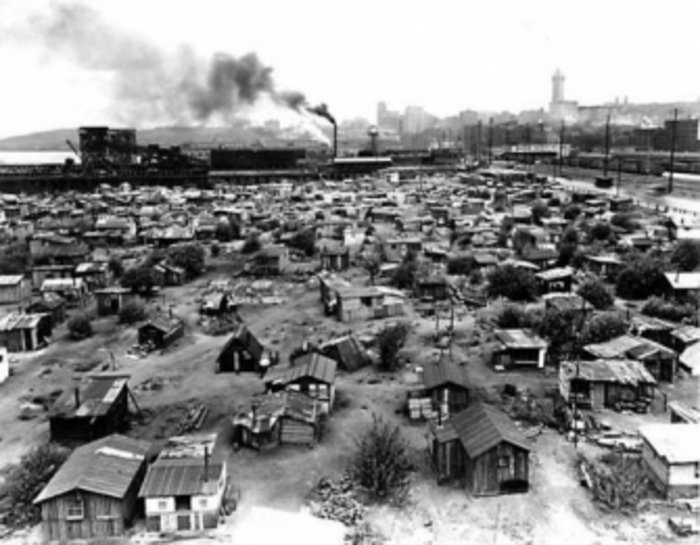

“Hooverville” was the term coined to describe the numerous shanty towns created by homeless men during the Great Depression in various American cities, an ironic reference, of course, to president Herbert Hoover. Nearly 80 years ago the spectacle of these Hoovervilles pushed Roosevelt and American labor politics toward the New Deal. In this light, one is led to wonder about the political significance of the similarly ironically named “New Year Hakenmura.” Does it indicate a tipping point in Japanese labor politics?

An American depression: Hooverville

What Drove the Dispatched Workers to Hakenmura?: The 1999 Dispatched Manpower Business Act

Why did the dispatched workers come to ask for help at Hakenmura? Certainly the global recession sparked by the U. S. financial crisis of the fall of 2008 is the direct cause. As demand for its exports collapsed in the final quarter of 2008, the Japanese economy contracted at its fastest pace in nearly 35 years. The government admits that the Japanese economy is facing the worst crisis since World War II. Even famed exporters including Toyota and Sony have not only slashed production and exports but have began to eliminate significant numbers of manufacturing jobs. Temporary workers are the first victims.2 It is estimated that by the end of 2009, about 150,000 dispatched workers will be unemployed. The workers who took refuge in Hakenmura were an early group of these growing numbers of the unemployed.

But the problem of the dispatched workers is in a sense more a political than an economic one: they are the victims of the 1999 Dispatched Manpower Business Act. The Dispatched Manpower Business Act was originally passed by the legislature (Diet) in 1985. It was based on an “open list method,” in which only those categories of employment listed by the government could be served by dispatch employment agencies. The act was revised in 1999, and a “negative list method” was adopted; agencies, that is, could provide contract labor for any jobs except for those specifically prohibited. As a result, jobs in the packaged delivery field and other related distribution industries were opened to the dispatch agencies, and dispatched jobs increased dramatically in these sectors. In 2004, jobs in manufacturing were also opened to dispatch agencies, where many disguised dispatched workers had already been hired. The number of dispatched workers in manufacturing industries skyrocketed to meet the higher demand of flexible production and low cost. At the same time, amendments to the Unemployment Insurance Law made it more difficult for these dispatched workers to obtain unemployment benefits.3

These legal changes were part of the deregulation policies of conservative governments, mainly led by the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) from the late 1990s. Japan’s labor unions could not significantly resist this neo-liberal reform of labor policy, which rapidly expanded the number of part-time and dispatched workers with no job security, few benefits, and low wages. Japanese labor policy making for some time had been worked out through negotiations among delegations of employers, unions, and public interest groups in tripartite advisory councils in the Ministry of Labor (former Ministry of Health, Labor, Welfare). Since the late 1990s, growing domestic and international pressure for economic deregulation had led top-down special committees attached to the Cabinet to intervene in such decision-making process, undercutting the role of the advisory councils and making it impossible for unions represented in these councils to veto deregulation measures.4 Furthermore, while unions were not wholly blind to the anticipated result of the deregulation, they were not greatly concerned with the problems of dispatched workers because they were not union members. Japanese unions have for decades been basically enterprise-based organizations, unions whose membership is usually limited to the regular employees of the enterprise, especially in the manufacturing sector. Dispatched workers have typically been excluded from these unions.

Who Invented Hakenmura?: The Community Union

While many non-profit organizations support the dispatched workers involved in Hakenmura and the working poor more generally, the organization at the center of this action was Zenkoku Komunitii Yunion Rengōkai (National Federation of Community Unions), abbreviated as Zenkoku Yunion. The organization is a network of community unions, established in 2002, and affiliated with Rengō (Japanese Trade Union Confederation, the biggest national labor federation in Japan) in 2003. The community union is not an enterprise-based union but a regional group whose members consist of diverse types of employees at different work places, including foreign workers. While Zenkoku Yunion is a nation-wide network of regional unions, it includes some unions which enroll specific types of employees across multiple companies and regions, such as lower-level managers and dispatched workers. Although the community unions are small (membership is one thousand at most), such unions are significant for supporting those workers who have typically been excluded from the Japanese regime of enterprise unionism.

The most important weapon of the community unions is an activist-style movement leadership which inspires members to confront their hardship. Indeed the union gives them strength. Leadership is not exercised through administrative positions and the entrenched power seen in mainstream unions, but through the energy, courage, intellect, organizational ability, and even life stories of activists and leaders. These militant minorities in the Japanese labor movement came from the ranks of veteran radical union officers, community organizers, student activists, and labor lawyers who have been very active in supporting workers outside the mainstream of large-firm employment, as well as workers suffering from unfair labor practices or in debt to loan sharks. These activists and leaders have forged a wide-ranging advocacy network that covers issues of workplace safety, environmental protection, and the rights of women, people with disabilities, and immigrants, along with the more traditional issues of work and employment relations such as job security and wages. The activity of the community union sometimes goes far beyond that of a trade union; these groups in fact serve as a sort of non-profit organization involved in various civic activities regarding working and living conditions, such as asylum for injured illegal foreign workers and their families, or support for abused women and workers suffering discrimination because of disabilities. Some of these unions also organize consumers’ and workers’ cooperatives, run by and for their members.

Because of the manifold functions and goals of their movement, community unions’ organizing methods are also distinctive. They often focus more on building a social movement than organizing as a labor union; they “promote causes, principled ideas, and norms, and they involve individuals advocating policy change.”5 For example, they recently united both a few managers and part-time workers at Japan McDonalds (the Japanese corporate entity of the global hamburger chain) to campaign over the issue of unpaid overtime work. Effectively using the media and filing suit in court, skillfully backed by various public activities, this community union eventually forced the company to pay for overtime work, despite its very small membership.

Preparations for Hakenmura were undertaken in just a couple of weeks after the idea was generated at a party held at the end of a session of telephone counseling for workers run by one member union of the Zenkoku Yunion federation. This group of activists, leaders, and friends of the Zenkoku Yunion alone had the movement skills and resources to set up this facility so successfully in such a short period of time.6

Why Was Hakenmura So Effective? The Media’s Rush to Labor

While Hakenmura could not have appeared without the creative thinking and action of Zenkoku Yunion and its movement colleagues, there is also no question that these activities became so well known only due to widespread media attention. In fact, the organizers of Hakenmura anticipated such attention from the outset; hence the decision to open the village in the Hibiya Park, in the heart of Tokyo.

As labor questions have become central issues in Japanese politics in recent years, the media have been a driving force bringing these matters to the political mainstream. This does not necessarily mean that the media were radicalized from the outset. Media interest in labor questions was driven originally by a desire for audience ratings or increased sales of books, newspapers, or magazines. The media have been treating labor problems as a scandal in an affluent society. By sensationalizing the labor question, Japanese media have aroused curiosity as to what is really happening in workplaces of well-known companies where unprecedented numbers of accidents, along with legally questionable treatment of workers, were uncovered.

During the 1980s, labor problems were assumed to be minor issues in Japan, which was widely perceived at home and globally as one of the most successful developed countries in the world. This perception changed when the story of the “Lost 15 Years” (Ushinawareta 15 Nen), Japan’s long economic slump extending from the early 1990s to the mid-2000s, became a dominant focus of media attention. People deplored the lost vitality of the Japanese economy and looked back nostalgically on past economic success. Since the mid-2000s, however, public discourse of lost economic vitality has given way to a discourse of lost equality in Japanese society. This is the narrative of a “divided society” (kakusa shakai). Japan had long been considered among the most egalitarian of industrialized countries. The lost fifteen years, however, generated a widening gap between rich and poor. One of the major reasons for this gap was the decline of the system of relatively long-term stable employment in major companies, seen as distinctive of Japanese society, which had supported a relatively equitable distribution of wealth. The retreat from commitment to long-term employment on the part of many firms produced a greater disparity in career opportunities and choices offered to the younger generation. The youth suffering diminished opportunities over the “Lost Fifteen Years” have been dubbed Japan’s “Rosu Gene” (Lost Generation) in the media.

Major Japanese newspapers, business magazines, and academic journals have shown that the gap in income and assets has been widening and that the poverty rate has increased dramatically in the last decade. By some measures, Japan’s poverty rate is now the second highest among industrialized countries, after the United States. This discourse of a “divided society” has fanned fears that Japanese society was coming to be divided into the two worlds of winners and losers (kachi gumi and maké gumi) among workers and their families.

Ever alert to new trends, the media have recently shifted their focus from the “divided society” to the “working poor” (Waakingu Pua). This term, referring to people who have jobs and work hard, but remain poor, was imported from the United States, where the category of the working poor encompasses low-paid workers, many from immigrant, single-parent and minority families, many in service industries, and non-mainstream workers with diverse backgrounds in various industries. The term has much the same meaning in Japan. Non-regular jobs (off the secure track of “regular employee” status) in Japan have drastically increased during the last decade, as unemployment has risen significantly.7 These jobs have been held by female part-time workers (labeled “pāto”, numbering 7.8 million in 2005), young part-time or casual workers (labeled “arubaito,” 3.4 million in 2005), contract workers, engaged directly by an employer on a short-term contract basis (numbering 2.8 million in 2005), and dispatched workers, engaged on limited-term contracts through a dispatching agency (1.1 million in 2005). Whereas one out of five or six employees in Japan fell into one or another of these non-regular categories in 1990, by 2005 almost one out of three was so employed.

The wages of atypical workers are approximately two-thirds to three-fourths the level of regular workers’ wages, even if they perform the same work. A growing number of employers indicated their intention to replace full-time with part-time workers because of the lower cost and greater flexibility. They were encouraged by the fact that Japan had no comprehensive law prohibiting discrimination against part-time or other non-regular workers, compared to full time, in wages, welfare programs, or social insurance. Furthermore, as already described, the Japanese conservative (or “neo-liberal”) government accelerated deregulation during these years, helping employers to more easily and flexibly hire non-regular workers, including dispatched workers.

The year 2006 was the turning point in the journalism of the emerging “labor scandal.” In July, an “NHK Special Documentary,” one of the nation’s most respected programs, featured the Japanese working poor. Sequels were aired in December 2006 and 2007. Other broadcast stations followed with similar documentary programs about the working poor in 2007 and 2008. Together these shows created a sensation, and the term “working poor” spread among ordinary people who felt a strong and growing interest in labor issues, especially as the problems of the working poor came to feel uncomfortably close to their own situation. Since then, labor questions pertaining not only to the working poor but also to companies’ illegal employment practices and government labor policies have often occupied the front pages of major newspapers and magazines and top news of national TV news programs.8 So-called “proletarian novels,” originally published in the 1920s exposing the brutal conditions aboard cannery ships in the northern Pacific Ocean or workers’ resistance to overseers, were republished and gained a large readership, especially among the youth. It appears these young readers found strong connections in these stories to their own circumstances. They also learned the meaning of solidarity among workers in these heroic narratives, something they had not experienced in their own lives.9 Newspaper editorials and the commentary of TV news anchors have been sympathetic to the working poor; the labor question was presented not as a matter of the responsibility of the individual worker (to find a job, for example), but as a matter of social justice. It was in this context of growing public concern that Hakenmura became a perfect event for the attention of media seeking to put forward an agenda of labor questions needing to be resolved.

Who Supported Hakenmura?: The United Front for Dispatched Workers

While Hakenmura provided an excellent subject for media eager to put forward a labor agenda, the village also offered a common space in which almost all labor organizations across the political spectrum could cooperate. Hakenmura gave rise to a united labor front to rescue jobless and homeless dispatched workers. The Japanese labor movement had seen no comparably wide-ranging united front over any labor issue since 1960. Hakenmura in this sense revived a tradition of Japanese social movement unionism in which unions and social movements sought to work hand-in-hand to address the suffering of people.

In the wake of World War II, Japanese labor unions experienced remarkable growth. By 1950 the unionization rate reached approximately 50 per cent. However, unions were organized at the level of individual enterprises, and working conditions were determined by collective bargaining between each enterprise union and the employer.10 When a new national labor federation, Sōhyō (The General Council of Trade Unions of Japan) was established in the early 1950s, it envisioned a labor movement that would reach out across the separate unionized sectors, and beyond them, to involve all unions and other workers’ organizations in broad-based social and political movements. While promoting the principle that “an injury to one is an injury to all” throughout the country, Sōhyō actively supported a strong peace movement in alliance with liberal intellectuals, the women’s movement, the farmers’ movement, Socialists, and Communists, and it supported long and aggressive strikes by enterprise-based unions.11

After the mid 1950s, Japanese management and unions at large enterprises reached settlements in which employees agreed to cooperate in an effort to increase productivity if employers agreed to guarantee their long-term employment and improve working conditions. Manufacturing companies in industries such as steel, shipbuilding, automobile, and electric machinery also established subcontracting systems for portions of their labor force, to reduce costs while securing employment and better working conditions for their own employees.12 Membership in enterprise unions was usually restricted to regular workers; non-regular workers (part-time or contract workers) were excluded. These large private enterprise unions led the way toward re-unification of the labor movement from the mid 1970s onwards. When Rengō was finally established in 1989, it was perceived as the political agent of big business unionism.

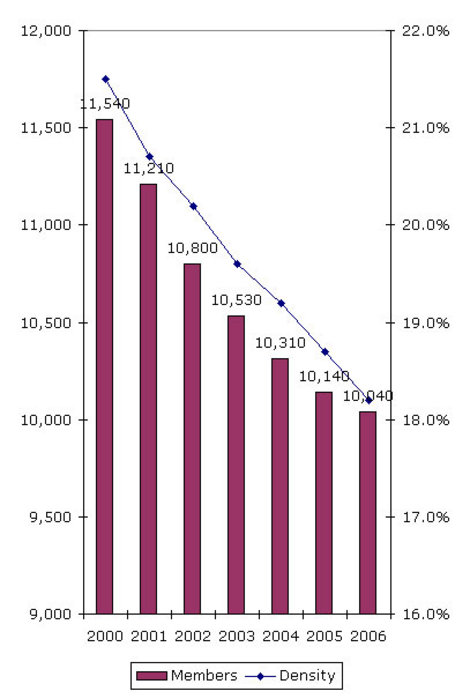

Since the 1990s, the Japanese labor movement has shrunk significantly. Many workers, particularly those employed in small to medium-sized enterprises and those with part-time jobs, have faced worsening job conditions without union protection. Japan’s unionization rate is now less than 19 per cent, and the unionization rate in small to medium-sized enterprises is much lower. This decline in union membership has reflected the rapid growth of offshore production. During the last decade alone, Japanese unions have lost 2 million members. But it is a loss in the vitality of the labor movement that has been more problematic than simply the decline in the unionization rate or the overall decline in membership. The number of labor disputes in which unions are engaged has been declining sharply for the past fifteen years. The number of strikes has also dropped steeply, and Japan could soon be a country without strikes of any kind. Even as numerous workers continued to suffer under terrible working conditions during these turbulent years, the labor movement seems no longer to be a vehicle for workers’ collective struggle against unfair labor practices.

As a result, workers have for some time been seeking alternative outlets for the sorts of advocacy or protection that unions might have once provided. Whistle blowing is one of them, and the number of reported corporate scandals and accidents has been steadily rising. While scandals and accidents are the result of worsened working conditions which unions might have addressed, it is also true that the rising number of reports is a result of workers’ declining loyalty to their companies and waning trust in their unions. It is clear that deteriorating standards of employment are taking a toll on Japanese working people. Some become severely physically and mentally ill, while others drop out of the work force altogether and become homeless. One indication that some workers retain a willingness to fight against unfair labor practices is the booming industry of individual labor disputes. The number of cases of civil litigation over labor problems has tripled since the early 1990s. Major issues in these litigation cases are claims for unpaid wages and retirement benefits, contestation of termination of employment, challenges to the validity of disadvantageous changes of working conditions and disadvantageous transfers. Labor administrative agencies now also receive an increasing number of complaints through their counseling services.13 Lacking an effective system to resolve individual labor disputes, the government in 2006 introduced the labor tribunal system. In 2004 it also reformed the unfair labor dispute adjudication system in order to speed up and strengthen its authority. The Labor Lawyers Association of Japan (LLAJ) currently has 1400 members, and young attorneys continue to join.14 Some of these lawyers have worked with Zenkoku Yunion and joined Hakenmura.

In this difficult situation, by broadening its goals and linking with other social groups, the movement has finally created a viable union sector for employees of small and medium-sized enterprises and non-regular workers. And, in support of this effort, the Rengō federation has switched from big enterprise unionism to social movement unionism since the beginning of the 2000s.15 Since then, Rengō has been articulating a set of goals much more in line with the changes taking place in the labor market, including, among other things, adjusting the unbalanced power relationship in the subcontracting system between large and small-to-medium-sized enterprises, offering counseling services for non-regular workers’ complaints about working conditions and unfair labor practices, organizing non-regular workers, strengthening the federation’s local branches and their welfare programs for joint activities and mutual aid for small to medium-sized enterprise unions and non-regular workers, and defining a social minimum of working conditions. In defining these goals one by one, Rengō adopted the rhetoric of social movement unionism, which emphasizes cooperation with other social movements on behalf of unorganized and disadvantaged workers. In this new context, Zenkoku Yunion has affiliated with Rengō.

Decline in Japanese union membership, 2000-2006

As mentioned earlier, Zenkoku Yunion served as a magnet for workers excluded from the Japanese regime of enterprise unionism. It has also been a magnet for radical labor, social, and political activists who have been marginalized since the Sōhyō-style social movement unionism declined in the early 1970s. These militant minorities have developed a web of connections with rank-and-file activists and minority leaders within Rengō, the National Labor Union Federation Japan (Zenrōren) led by the Communist Party (JCP), the National Labor Union Conference (Zenrōkyō) led by the former Japan Socialist Party (JSP), new left labor groups, and new social movement groups for youth, women, and foreign workers. These groups together have recently organized the Anti-Poverty Network (Han Hinkon Nettowaaku), comprising the core members of Hakenmura’s executive committee. In other words, Zenkoku Yunion is playing an indispensable role in support of Rengo’s practice of social movement unionism.

Recently Zenrōren has been very active in addressing the issue of the working poor. The Communist Party’s radical argument on the issue has attracted the young generation. Severely criticizing enterprise unionism for its failure to help the dispatched workers, the media have given positive attention to these leftist activities. And, behind the scenes, Rengō has been involved in the various activities of Zenkoku Yunion and its movement colleagues. When the Hakenmura project was initiated, its organizers asked Rengō to make great efforts in the background. In fact, Hakenmura relied on Rengō’s physical resources, manpower, and political connections. This would be the first time for Rengō’s members to work officially with members of Zenrōren and Zenrōkyō in a campaign; since Rengō was established twenty years ago, these three federations have been fighting against each other. When Sōhyō was absorbed into Rengō, Communist-led groups within Sōhyō split off from some of its constituent unions and founded Zenrōren, and Zenrōren originally tried to compete with Rengō. When it proved difficult to compete effectively, Zenrōren sought to penetrate Rengō or work with it. Rengō has until now rejected Zenrōren’s overtures because of a strong anti-Communist allergy within Rengō. But now Rengō seems ready to work with Zenrōren and other groups from the perspective of social movement unionism, so long as it is beneficial for all workers and their families. Hakenmura was the first test of this stance.

Why the Government was Supportive of Hakenmura?: The Re-regulation Offensive

The united front in support of the dispatched workers was not limited to the labor and social movement. One surprising turn of events came when the Hakenmura executive committee asked the MHLW to open its building for the workers’ lodging on January 2, and the ministry promptly agreed. This was the first time it has offered its building for workers’ lodging. Until they heard the announcement, few if any observers would have expected MHLW take this step. And surely no one expected that the decision would be made so quickly, on January 2, a national holiday when ordinarily there was nobody at all working. But MHLW acted as if it had been standing by, ready to help. Why was the ministry so accommodating to Hakenmura? The reason is that the foundation for a united political front, to be sure a carefully calculated one, had been laid for the bureaucrats as well. In fact, politicians of all the parties, from the LDP to the JCP, had visited Hakenmura to learn how they could help the workers. Of course, their visits were aired on national news programs. The person in charge of opening the building was a vice minister of the MHLW. He must have discussed the decision with the minister. One of the leaders of the Democratic Party who visited Hakenmura was a former minister of MHLW, and he likely called the minister requesting him to help the workers.

What brought about this remarkably united political front? It represented a culmination of the mainstreaming of the labor question in Japanese politics, as all parties sought to position themselves as the friend of the workers. This shift was apparent earlier in the fight against what is called the “white-collar exemption.” This exemption represented a deregulation of limits on working hours; it exempted white-collar employees, whose annual income met a minimum standard, from the protection of the eight-hour day and the 40-hour work week, meaning they would no longer receive overtime pay if they worked beyond these limits. After this exemption had been discussed in the advisory council of MHLW for several years, disagreement between representatives of labor and management stalled any movement on the issue during the summer 2006. Nevertheless, MHLW was preparing to submit a bill to the winter 2007 session of the Diet in line with the demands of management organizations. The Rengō federation, and especially Zenkoku Yunion, campaigned vigorously against the bill. Their movement peaked with several large gatherings and demonstrations. At this point, with dramatic headlines, the media threw their support behind the Rengō campaign. As a result, strong sentiment against the bill spread among the public. On the grounds that the bill was misunderstood, in January 2007 the Abe LDP government finally abandoned its plan to submit it, while stating its intention to submit other bills favorable to non-regular workers.

This case illustrates the process by which the labor question has been mainstreamed in Japanese politics. First of all, labor issues became critical for the government. In this instance, the most compelling reason for the government to abandon the bill was anxiety about how it would negatively influence the Upper House election, scheduled for the summer of 2007. It was most significant, in this regard, that as the campaign against the bill intensified, the Kōmeitō (the Clean Government Party, CGP), a member of the ruling coalition, was the first to vigorously oppose the bill. CGP was competing with the JCP, which had already joined the campaign, for the support of working and middle-class voters who suffer disproportionately from the deregulation of work rules. The LDP pressured the government to abandon the bill because it desperately needed CGP support.16

Growing popular interest in labor questions and concern with the “divided society” have provided politicians with a new rhetoric concerning the various issues involved, leading them to seek new bases of support. This shift certainly occurred within the LDP. The ruling party has been much more enthusiastic than the opposition Democratic Party, which Rengō had supported, in introducing new labor policies to ameliorate the status and working and living conditions of non-regular workers. In fact, one LDP leader with a strong neo-liberal disposition declared that the party should become the standard-bearer of part-time workers.17 He believed that the LDP could promote equality of opportunity and “second chances” for underprivileged workers much more effectively than more radical schemes to improve working and living conditions. From the viewpoint of equality of opportunity, the LDP leader was also prone to attack the “vested interest” privileges of public employees. Similarly the policies of the Abe government aimed at giving non-regular workers equal opportunity, not directly through promotions or pay raises, but by removing legal impediments to advances in position or pay. By such policies, the LDP leadership expected to drive a wedge among workers, the mainstay of the opposition party, to divide Rengō, and to attract some working class support to the LDP. But as neo- liberalism has declined even in the LDP, this group’s influence over the government’s labor policy has been diminished.

While the debate over the white-collar exemption was heated, other LDP leaders formed a special committee on labor policy within the party to intervene in the policy making process. Their aim was to undermine the existing labor policy community, in which Rengō, Keidanren (the Japanese Federation of Economic Organizations), and MHLW have dominated.18 This group’s policy tendency is more anti-deregulation, especially in labor policy. Having specialists of labor policy among its members, the committee has led the LDP’s labor policy development and implementation since the Abe government. While they have been very active in connecting with other labor policy networks, they have also sent their members as representatives of the LDP to symposiums and campaigns organized by Zenkoku Yunion. Their policy response to the working poor has been quick and flexible. Disappointed with lack of a clear labor policy among specialist groups within the Democratic Party, Rengō sometimes has consulted unofficially with the LDP committee.

Seeing the reverse tide of labor policy flowing from deregulation to reregulation, MHLW has tried to swim with the current to regain its status as a friend of workers, a position anticipated when the Ministry of Labor was founded immediately after World War II. Moving with public opinion also represented a chance to recover its honor, which had been severely damaged in the scandal of massive loss of pension records by one MHLW agency. The MHLW was not the only organization that had to persevere and endure for years in the face of the deregulation policy and anti-bureaucratic sentiment of the Koizumi government.19 The Ministry of Finance is another bureaucratic organization that has tried to float on the stream of active government to help suffering workers. Both ministries are currently acceding to Rengō demands on labor policy; some of the programs, laws, and budget measures proposed by these ministries are products of joint work with Rengō.

In this fashion, the mainstreaming of labor politics on a complicated, competitive terrain has created a favorable political context and led the government to be supportive of Hakenmura.

A Critical Moment for Japanese Labor Politics

After the Dispatch Workers Village at Hibiya Part was closed, similar facilities were organized by local union groups and other non-profit organizations elsewhere, and several more are planned to open in other cities across Japan. Although the organizations responsible are not necessarily members of Zenkoku Yunion, they use the name of Hakenmura for their activities. There is no question that Hakenmura captured attention at a critical moment for labor, the labor movement, and labor politics in contemporary Japan. It is also certain that Hakenmura opens a window on the state of mind of people in Japan today: if some among us are suffering poverty, why don’t we help them? This is a habit of the heart which Japanese people have for some time lost. In this regard, the New Year Dispatch Workers Village might mark a cultural as well as a political tipping point.

Toru Shinoda is professor of Comparative Labor Politics at the Faculty of Social Sciences in Waseda University, Tokyo, Japan. His current research interest is a trans-Pacific history of the labor movement. His many publications on Japanese and US labor movement include “Introduction: The return of Japanese labor? The mainstreaming of the labor question in Japanese politics,” Labor History, Vol. 49, No. 2, May 2008.

He wrote this article for The Asia-Pacific Journal.

Posted at The Asia-Pacific Journal on April 4, 2009.

Recommended citation: Toru Shinoda, “Which Side Are You On?: Hakenmura and the Working Poor as a Tipping Point in Japanese Labor Politics,”The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol 14-3-09, April 4, 2009.

Notes

[1] On recent Japanese labor politics, see Toru Shinoda, “Introduction: The return of Japanese labor? The mainstreaming of the labor question in Japanese politics,” Labor History, Vol. 49, No. 2, May 2008.

[2] “Steep Export Slide Pummels Japan: Annualized 4th-quarter GDP plunged 12.7%; further declines predicted,” The Wall Street Journal, February 16, 2009.

[3] Akira Takai and Momoyo Kamo, Dōsuru Haken Giri 2009 Nen Mondai (How do we cope with the cancellation in the middle of the term of dispatch contracts? The problem of the year of 2009), Tokyo: Junpōsha, 2009.

[4] Mari Miura, “The New Politics of Labor: Shifting veto points and representing the un-organized,” F-93, Institute of Social Science (University of Tokyo), Domestic Politics Project No. 3, July 2001.

[5] Margaret E. Keck and Kathryn Sikkink, Activists beyond Borders: Advocacy Networks in International Politics, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1998, pp.8-9.

[6] For more detail on the community unions and their background, see Akira Suzuki, “Community Unions in Japan: Similarities and differences of region-based labour movements between Japan and other industrialized countries, Economic and Industrial Democracy, Vol. 29, No. 4, pp. 492-520, November 2008.

[7] “Nihon Ban Wākingu Pūa: Hataraitemo Mazushii Hitotachi (Japanese Working Poor: People Work Hard But Are Still Poor),” Weekly Tōyō Keizai, 16 September 16 2006.

[8] Media Sōgō Kenkyuujo (Media Research Institute), ed. Hinkon Hōdō: Shin Jiyuu Shugi no Jitsuzō wo Abaku: Media Sōken Bukkuretto No. 12 (Journalism of Poverty: exposing the reality of neo-liberalism, Media Research Institute Booklet No. 12), Tokyo: Kadensha, 2008.

[9] Norma Field, “Commercial Appetite and Human Need: The accidental and fated revival of Kobayashi Takiji’s Cannery Ship,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 8-8-09, February 22, 2009.

[10] Toru Shinoda, “Rengo and Policy Participation: Japanese-style neo-corporatism?” in Sako and Sato eds. Japanese Labour and Management in Transition, p.189.

[11] Toru Shinoda, “’Kigyō Betsu Kumiai wo Chūshin to shita Minshū Kumiai’ toha –Shakai Undō teki Rōdō Kumiai to shiteno Takano SŌHYŌ (Jō)(Ge)”[in Japanese](What is a ‘Company-based Popular Union’?: Takano Sōhyō as a social movement unionism, 1, 2), Ōhara Shaki Mondai Kenkyūjo Zasshi (The Journal of Ohara Institute for Social Research), No. 564, 565, November, December 2005.

[12] Beverly J. Silver, Forces of Labor: Workers’ Movement and Globalization since 1870, Cambridge University Press, 2003, p.42.

[13] Kazuo Sugeno, “Judicial Reform and the Reform of the Labor Dispute Resolution System,” in Japan Labor Review, Vol. 3, No. 1, Winter 2006, p.7.

[14] http://homepage1.nifty.com/rouben/ downloaded June 26, 2006.

[15] Frege, Heery, and Turner argue that trade union movements often try to “recreate themselves as social movements” when they seek to revitalize. Their “prescription of ‘social movement unionism’ lists the following: 1) Broadening movement goals to “encompass social progress beyond the immediate employment relationship”; 2) Forming “coalitions with other social progressive forces,” including new social movements on “social identity, the environment, and globalization”; and 3) Rediscovering unions’ “capacity to mobilize workers in campaigns for workplace and wider social justice.” Carola Frege, Edmund Heery, and Lowell Turner, “The New Solidarity? Trade Union Coalition-Building in Five Countries,” in Carola Frege and John Kelly eds. Varieties of Unionism: Strategies for Union Revitalization in a Globalizing Economy, Oxford University Press, 2004, p.137.

[16] The Asahi, January 7, 12, 19, February 7, and 8, 2007.

[17] Hidenao Nakagawa, Ageshio no Jidai: GDP 1000 Chō En Keikaku [in Japanese](The Age of the rising tide: GDP 1000 billion yen plan), Kōdan Sha, December 2006.

[18] “’Keieisha no Ronri’ ni Igi wo Tonaeru Jimin Rōdō Seisaku no Nejire Genshō(The twisted LDP labor policy against ‘the logic of management’), Weekly Ekonomisuto, January 20, 2007, pp.25-26.

[19] Jin Igarashi, Rōdō Saikisei: Hanten no Kōzu wo Yomitoku [in Japanese](Labor Reregulation: How the reversal happened), Chukuma Shinsho, 2008.