By Tessa Morris-Suzuki

“We got on the boat in Busan. Don’t know where we got off… We came on a fishing boat. A little boat, it was. The waves were that high, and we went right over them. What month would it have been? Can’t remember now.

They say you really get to know people when you go on a boat with them, or live with them. It was so dark in that boat, you couldn’t even tell who was in there. Everyone jammed together in this little space – so small, we were sitting right on top of one another. When people said their kids were being smothered, they were just ignored. There were dozens of people – thirty or forty in that little boat. That’s why we were sitting on top of each other. It was so crowded you couldn’t eat rice or anything like that. Two nights we went without eating… Of course in those days it was a people-smuggling boat [yami no fune]. People came on those boats from Jeju or Busan – that was when I was twenty-nine”[1]

This story was told to researcher Koh Sunhui in 1993 by a woman, then in her late 60s, who had arrived in Osaka in 1955 and lived there ever since, raising her family and doing outwork, sewing slippers. When Koh interviewed her she had two grandchildren, and was attending night school to catch up on the school education which she had missed in her own childhood.

Growth Without Immigrants?

There is a theme which runs like a mantra through countless texts on Japan’s economy and society. It goes like this:

“Japan’s economic boom after the Second World War did not lead to the recruitment of foreign workers, as it did in western Europe.”[2]

“Japan distinguished itself from many European labour importing countries by achieving economic growth without attracting foreign workers. It was not in the 1960s but in the 1980s that Japan’s economy became dependent upon foreign workers.”[3]

“Unlike most European labour importing countries… Japan managed to achieve high levels of economic growth without relying on foreign manual workers until the early 1980s.”[4]

“Until the beginning of the 1980s Japan had never considered itself to be a host to immigrants with the exception of the Korean and Chinese who were brought to Japan as forced labourers before and during the Second World War”.[5]

Interestingly, these quotations come from the writings, not of people who subscribe to larger myths of Japanese ethnic homogeneity, but of researchers who are at pains to emphasise the presence of diverse foreign communities in Japan. Looking back at my own work, I find statements reflecting a similar assumption that immigration to Japan occurred in two quite distinct waves: one during the colonial period up to 1945, and the other beginning around 1980. I too unquestioningly accepted the notion that the years from 1945 to the last quarter of the twentieth century constituted a “blank space” in the history of immigration to Japan. [6] But recent encounters with many stories, among them the account by the woman in Osaka of her arrival in Japan in 1955, have forced me to look again at that assumption. This article is a rethinking of the “blank space”.

Historians and social scientists weave words together like nets to catch the truth: and, like nets, the words leave spaces into which parts of the past continually disappear. The life of the woman interviewed by Koh Sunhui, and the lives of uncounted others like her, are among the stories which have slipped unnoticed through conventional accounts of Japan’s migration history. Looking more closely at these accounts, we can start to see some of the linguistic holes into which they have disappeared.

One major English-language study of migrant labour in Japan illustrates the problem well. The discussion moves smoothly from a statement that Japan’s economy did not become “dependent upon foreign workers” until the 1980s, to the question: “how could Japan have successfully achieved economic growth without importing foreign workers in the 1960s and 1970s?”[7] In the process, two quite different assertions are elided. The first assertion, which still seems correct, is that the Japanese economy did not “depend” on foreign labour in the high growth era. While foreign workers formed a substantial proportion of the workforce in some European countries during the 1960s and 1970s, in Japan their number, in relation to the total size of the workforce, was far too small to bear the weight of notions like “dependence”.

But this is quite different from saying that Japan achieved its high growth “without importing” foreign workers. Migrants did come, and some also left again. Some stayed just a few months, others for a lifetime. Most worked in Japan, and their presence demands acknowledgement for several reasons. First, the experience of migration had a formative effect on many thousands of individual lives. Second, postwar immigration and official responses to that immigration shaped Japan’s migration and border control policies in ways which continue to have a profound impact to the present day. Third, although their influence on macroeconomic growth may have been very small, postwar migrants made important contributions to the destiny of particular industries and particular communities within Japan. Finally, a closer look at immigration to Japan between the late 1940s and the 1980s opens up new ways of thinking about the nature of borders and of Japan’s relationship with its closest neighbours.

The accepted narrative of Japan’s migration history, however, remains framed by that powerful image of Japan’s postwar development as “growth without migrant workers”. This narrative runs roughly as follows. The prewar colonial period generated large-scale movements of people, including mass emigration from Japan to the colonial empire and beyond, and the forced and voluntary entry of Koreans, Chinese and others to Japan. As a result, there were over two million Koreans, and smaller numbers of Chinese and Taiwanese residents in Japan at the end of the Pacific War. Of these almost three-quarters were repatriated after the war, but their places in the workforce were filled by the repatriation of more than six million Japanese from all over the former empire, and by rural-urban migration within Japan. During the 1950s and early 1960s there was a small outflow of Japanese emigrants to Latin America, and rather more significant outflow of people from US-occupied Okinawa to the same destination. Other than this, however, postwar Japan was characterized above all by its lack of international migration at least until the 1980s (though a few scholars also note that the post-1980 migration boom was prefigured by an inflow of female workers to the Japanese sex industry which began in the second half of the 1970s[8].

Immigration during the years from 1945 to the late 1970s is wholly missing from this story (as is the post-occupation emigration of foreign residents from Japan). Yet such immigration certainly occurred, and this essay seeks to explore its nature and its implications for our understanding of migration history in the Japanese context. The exploration is, of necessity, preliminary and incomplete. As we shall see, it is impossible to provide accurate statistics of migrants who entered Japan between 1946 and the late 1970s, but it seems clear that they numbered at least in the tens of thousands, and possibly in the hundreds of thousands. Documentary material is more readily available for the postwar occupation period and the 1950s than it is for the 1960s and 1970s: a fact also reflected in the coverage of the discussion presented here.

This discussion also focuses mainly on migration from Korea, which was by far the largest source of postwar immigrants. However, a variety of other smaller migratory flows also await scholarly study. The postwar repatriation of Taiwanese and Chinese residents in Japan, and the entry of Taiwanese and Chinese migrants in the postwar decades, are important and little-explored topics. Another neglected issue is cross border movement between Okinawa and the rest of Asia. Since Okinawa was under US occupation until 1972, it operated under a migration regime different from the one described here. Postwar immigrants to Okinawa included Taiwanese workers brought in to cultivate pineapple plantations, and workers from the Philippines employed in or around US military bases. The history of their lives both before and after Okinawan reversion remain important topics of study. Many of the questions about borders, nationality and Japan’s immigration policy raised in this essay are also of relevance to these further dimensions of postwar migration which, for reasons of space, are not examined here.

For similar reasons, it is not possible to provide a comprehensive comparison of Japanese policies with those of other countries. As I indicate, however, Japan’s postwar migration controls were not unique, but were in fact strongly influenced by US models. What was distinctive about the Japanese experience, however, was how migration controls and nationality policies interacted to produce a system that had particularly far-reaching consequences for the country’s largest foreign community.

The Language of Invisibility

Statistics themselves have the capacity to render people invisible. Consider this description of the background to contemporary migration issues in Japan, which accompanies a table showing the number of legally registered aliens in Japan between 1920 and 1991: “Since overrunning (but not completely exterminating) the indigenous Ainu and Okinawan cultures on the islands occupied by Japan, the Japanese have enjoyed centuries of ethnic and cultural stability… Between 1950 and 1988 the percentage of foreigners in the total population of Japan was consistently about 0.6 percent”.[9] The figures in the table support this image of stability: they suggest, to be precise, that the percentage of legally registered foreigners in the Japanese population was 0.72% in 1950, 0.68% in 1970, and 0.70% in 1985.[10]

But constant percentages do not necessarily mean an absence of movement or change. For one thing, as we shall see, there was in fact a substantial exodus of over 70,000 Koreans in the years 1959 to 1961. [11] At the same time, in a large and growing population, stable percentages represent a growth in the actual number of registered foreign residents in Japan by over a quarter of a million: by 109,852 between 1950 and 1970, and a further 142,064 between 1970 and 1985 (though this is partly accounted for by natural increase, since children born in Japan to foreign fathers were also foreigners).

Furthermore, reliance on the official figures raises important problems. Faith in government data is particularly evident in studies of Japan, where the presence of a well-organized and statistically-minded bureaucracy induces a ready acceptance of the official record. Yet in fact (as government officials themselves occasionally admit) the apparently precise figures for registered foreigners in postwar Japan bears an uncertain relationship to reality. The growth in the number of documented foreign residents in Japan between 1950 and 1970 was at least partly a result of the introduction of more rigorous registration procedures[12]; more importantly, most immigration to Japan in the postwar decades took the form of undocumented “illegal” entry, and does not appear in the official record at all. Bearing that in mind, the postwar decades begin to look less like a time of stability and closure than a time of complex and poorly recorded cross-border flows.

The very words that we use to speak of migration also create their own silences. In the Japanese context, the debate about post-1980 immigration has been framed by a conceptual division between two groups. On the one hand, there are “old-comers”, Korean and other imperial subjects who came to Japan in the colonial period, and their descendants, many of whom are now third or fourth generation residents in Japan; on the other, there are recently arrived “new comers”, members of the post-1980 wave of immigration from East and Southeast Asia and beyond. These two groups, we are told, are “completely different from each other, not only in their ability to speak Japanese but also in the labour markets in which they participate.”[13] This dichotomy leaves us bereft of words with which to speak about the immigrants of the 1950s, 1960s and early 1970s, who (like the “oldcomers”) were mostly Korean, and in some cases had lived in Japan before or during the war, but who were also (like many of the “newcomers”) “illegal migrants”, often employed for low wages in small firms.

More generally, in debating global migration issues, scholars repeatedly speak of “immigrant labour”, “guest workers”. These terms dramatically simplify the complexity of the migrant experience, reducing migrants to labouring bodies whose function in history is to contribute to the growth of gross national product. Even in European countries with large “guest worker” programs, such terms obscure essential aspects of migration history. Applied to postwar Japan, they become even less helpful. The non-Japanese migrants who entered the country without official documentation between 1946 and 1980, mostly from Korea, did so for a great variety of reasons. Some came to join family already in Japan, some to escape poverty, others to enter high school or university, to evade conscription or to escape from war, social disruption or political persecution. Many came for a combination of several of these reasons.

Once in Japan, most became workers, generally employed for low wages and in small firms. They came to be disproportionately concentrated in the Kansai region of western Japan, and in manufacturing industries such as plastics, metal plating, garment manufacture, as well as in the entertainment industry, including the pinball parlour [pachinko] business – an industry which by the end of the twentieth century was estimated to be larger (in terms of annual sales) than the steel industry.[14] Many undocumented migrants worked in companies run by other members of the Korean community, but some were employed by relatively large Japanese companies. In the early 1970s, for example, a Tokyo subcontractor producing steel products for a major Japanese corporation was found to be systematically recruiting dozens of “illegal immigrants” from Korea.[15] A small number of such migrants even achieved promotion to senior managerial levels: in 1964, one of the leading managers of Coca-Cola Japan was “exposed” in the media as a Korean illegal migrant, who had held a post in the South Korean bureaucracy before fleeing to Japan in a “people smuggling” boat at the time of the Korean War.[16] Immigrants clearly contributed to Japan’s postwar growth. But they were not viewed at the time as “guest workers”. Rather, official documents and the popular media consistently referred to them as mikkôsha [stowaways, people who smuggle themselves into the country] or as senzai fuhô nyûkokusha [illegal entrants who live concealed lives], words laden with overtones of marginality, invisibility, lives lived beyond the reach of the law.

The Origins of “Illegality”

Postwar immigrants have thus remained “invisible” to large areas of officialdom and to many scholars of Japanese migration. Their absence from the official record was, of course, in part a consequence of the fact that most were “illegal”. Their “illegal” status means that they were never counted in government statistics, and that the migrants themselves – who lived in constant fear of discovery, internment and deportation – were unwilling to speak about their experiences. Even today, many migrants from this era and their descendants are reluctant to discuss personal histories in public. But there are nonetheless people both in Japan and in South Korea (from where most of the migrants came) who have always been aware of their presence. The postwar immigrants were generally conscious of being part of a complex and interconnected community, and their presence was often visible to neighbours – particularly to people (whether Korean or Japanese) who lived in areas of Osaka, Kobe or Yokohama with large immigrant populations.[17]

Besides, “illegality” does not entirely explain the way that postwar migrants have been written out of history, for, interestingly enough, there has been very widespread public and scholarly discussion of post-1980s “illegal migration” to Japan. Since 1990, indeed, the government itself has regularly published seemingly meticulous data on the numbers of “illegal migrants” in Japan. In the year 2000, for example, the official figure was 224,067, the largest numbers coming from South Korea, the Philippines and China (though this figure too is of course a guesstimate based largely on the number of visa overstayers).[18] To understand both the “illegality” and the “invisibility” of postwar migrants it is therefore necessary to begin by looking a little more closely at the historical context in which they came to Japan.

Japan’s prewar colonial expansion, as we have seen, generated enormous cross-border flows of people, both forced and voluntary. By the end of the Pacific War, there were not only over 2 million Koreans in Japan but also more than 2 million in Manchuria and other parts of China, and an estimated 30,000-40,000 in the former Japanese colony of Karafuto [Southern Sakhalin].[19] As well as these mass migratory movements, there was a great deal of short-term movement back and forth across the internal boundaries of the empire. For example, merchants from northern Taiwan regularly came to sell their wares in the southernmost islands of Okinawa Prefecture[20]; divers from Jeju Island in Korea frequently crossed to dive for shellfish off Kyushu and Shikoku[21]; and residents of the Japanese island of Tsushima often sent their children to school in the Korean city of Busan, which was nearer to their homes than any Japanese city[22].

After the War, large parts of Northeast Asia were occupied by the victorious Allies, and Japan was divided into two parts under separate occupation regimes. The major part of the country was placed under an allied occupation whose headquarters [the Supreme Command Allied Powers – SCAP] exercised control through a Japanese administration, while the “Nansei [Southwestern] Islands”[23] were placed under direct US military rule. Meanwhile, the southern half of the newly independent Korea was also occupied by the United States, which proceeded to install the right-wing regime of Syngman Rhee, while Soviet troops moved in to occupy the northern half of the Korean Peninsula.

The Allied occupation forces in Japan and South Korea tended to regard colonial migrants as “displaced persons”, and initiated massive repatriation programs to “re-place” them – to put them back where they belonged. It was generally assumed that repatriation would result in the return to Korea of almost all the two million Korean in Japan. In fact, however, it soon became clear that not all were immediately eager to return. Some had lived in Japan for most of their lives. Besides, the extremely chaotic and unstable situation in postwar Korea meant that many had no homes or jobs to return to.

Indeed, by the early months of 1946 it became obvious to the occupation authorities that a considerable number of Koreans who had been repatriated were actually re-entering Japan in small boats. As concern mounted about this uncontrolled cross-border movement, occupation forces commissioned a Korean resident in Japan, Cho Rinsik, to examine the reasons for this influx of “stowaways” from Korea. After visiting a camp in Kyushu where “stowaways” were detained, Cho reported that “these stowaways are all former residents of Japan, and 80%…come to Japan on account of hard living and for the procuration of daily food”. In particular, Cho pointed out that people repatriated from Japan to Korea had been forced to leave behind “real estate, property or savings and deposits in Japan”, and were permitted to take with them only 1000 yen in cash: “ and what is more, they had to pay up to 1000 yen for half a bushel of rice [in Korea]. This means that they could not live a month with the money they had brought with them”. About 10% of the re-entrants, according to Cho, came to buy goods which were in scarce supply in Korea, while a further 10% came because of “impelling circumstances”. Typical of these circumstances was the situation where “prior to their repatriation to Korea, a husband, parent or son first repatriated, leaving the family in Japan, in order to prepare family repatriation en bloc. So the ‘harbingers’ naturally wish to return to Japan after preparation is done or if they find that living in Korea is impossible”. [24]

In retrospect, the Occupation Authorities’ response to the “stowaway” problem seems extraordinary. It is common for the break-up of empires to result in large cross-border movements of people, particularly when colonizing power and colony are geographically close to one another. In many cases, special provisions have been made to allow the reunion of families divided by new post-colonial borders.[25] The occupation forces in Japan and Korea, however, made no such provisions. On the contrary, during the first seven months of 1946 they issued a series of ordinances prohibiting cross border movement between the two countries without the express permission of the Supreme Commander Allied Powers. In practice, this meant that it became impossible for ordinary Koreans to enter Japan, and this blanket ban applied even to the re-entry of people who had lived all their lives in Japan, and who had left their families behind there when they returned to Korea for visits that were supposed to last only a few weeks or months..[26]

The tough approach to border controls was initially justified on public health grounds: in the summer of 1946 there was an epidemic of cholera in Korea, and SCAP felt it necessary to close the border to prevent this spreading to Japan. (Given the fact that large-scale repatriation of Japanese from the colonies continued unabated, however, it was not surprising that several hundred cholera cases were also reported in Japan in 1946). But (as I have noted in an earlier essay) once in place, the border controls remained long after the cholera scare had ended.[27] Increasingly, they came to be justified, not in terms of public health, but in terms of the need to prevent the cross border movement of black-marketeers and, above all, of Communists and other “subversives”.

The practical problems which the closing of the border created for Koreans in Japan and their families are vividly illustrated by individual stories from a group of some 280 “illegal immigrants” from Korea, arrested by Japanese police on the coast of Shikoku in October 1948. One of those in the group, a 51-year-old man from Jeju, had come to collect the ashes of his elder brother, who had lived and died in Osaka, for burial in his home village. Another, a 34-year-old sewing machine salesman from Osaka, had returned to the family home in Jeju to visit his dying mother, and was now trying to make his way back to the city where he lived and worked. Among the others were an eight-year old girl and her seven-year-old brother, trying to rejoin their mother who lived in Japan. All, along with the rest of the border-crossers arrested in the same area, were interned in Hario Detention Center near Nagasaki, and summarily deported to South Korea without trial.[28]

As Cold War tensions heightened, indeed, the border between Japan and both halves of the Korean peninsula became barricaded by restrictions from all sides. Both the Kim Il-Sung regime in North Korea and the Syngman Rhee regime in South Korea imposed tight constraints on exit, making it impossible for most Koreans to obtain passports for overseas travel, while the Japanese government, which regained control of immigration policy (except to Okinawa) from 1952, maintained sweeping restrictions on entry. In 1947, urged on by SCAP, the Japanese government introduced an Alien Registration Ordinance requiring foreigners in Japan (other than members of the occupation forces) to carry identity cards at all times.[29] Both SCAP’s entry controls and the Alien Registration ordinance, it should be noted, were applied to Koreans and Taiwanese despite the fact that they were at that time Japanese nationals in terms of international law. In the colonial period, Korean and Taiwanese colonial subjects had possessed Japanese nationality (although this did not bring with it equal rights as citizens). Those who migrated to Japan and remained there after the war retained their Japanese nationality throughout the occupation.

By the end of the occupation, however, two measures had radically undermined their legal position: these measures were the Migration Control Ordinance and the abrogation of the Japanese nationality of former colonial subjects. Japan’s 1951 Migration Control Ordinance [Shutsunyukoku Kanri Rei], drawn up after close consultation with US immigration experts, made entry relatively easy for short term business migrants, journalists, missionaries and others, but almost entirely prohibited the entry of foreign workers. It also said nothing at all about the status of Korean and Taiwanese residents in Japan, because they were not officially “foreigners” at that time. Meanwhile, intense debates were taking place about the future nationality of former colonial subjects living in Japan. Occupation authority legal advisors argued that Korean and Taiwanese residents should ultimately be given a choice of retaining Japanese nationality or taking the nationality of their newly independent homelands.[30]

However, in part because of the complexities surrounding the division of the Korean peninsula, this choice was never offered. Instead, in April 1952, on the day when the implementation of the San Francisco Peace Treaty ended the occupation, the Japanese government unilaterally revoked the Japanese nationality of Taiwanese and Koreans in Japan. Those who lost their nationality simultaneously lost a wide range of rights (including rights to public-sector employment and to many forms of welfare). They were also left without any clearly-defined residence status or any assured right to re-enter Japan if they travelled abroad. Their position was defined only by a vaguely worded supplementary regulation passed in 1952, which allowed those who had lived in Japan continuously since colonial times (and their children born between 1945 and 1952) to remain until their status was determined under some other law.[31]

It was this “Catch 22” relationship between immigration law and nationality law which gave the postwar Japanese migration regime some of its unusually repressive characteristics. In this context, it is worth stressing that post-colonial settlements in a number of other parts of the world made special provision for the residence rights of former colonial subjects who had migrated to the colonizing power.[32]

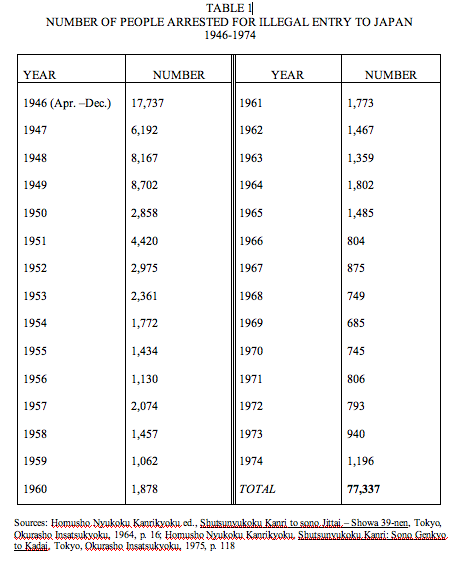

Stolen Voices

Yet despite draconian border-control policies, the flow of people across the frontier continued. Between April and December 1946, 17,787 “illegal entrants” to Japan were detained by police or members of the Allied Occupation Forces, and although the number fell in subsequent years, by 1951, the last year of the Allied Occupation, a total of 48,076 “illegal entrants” (45,960 from Korea, 1,704 from the “Nansei Islands”, 410 from China and 2 from elsewhere) had been arrested.[33] The authorities were well aware that the real number of entrants was much higher, since many undocumented entrants escaped detection. As SCAP officials noted with concern in 1948, “statistical studies indicate that approximately 50% of the illegal entrants are not apprehended, and only 25% of the ships involved in this traffic are captured.”[34] Given the chaotic nature of the times, the quality of the “statistical studies” is open to question, but there can be no doubting the fact that a high proportion of “stowaways” escaped detection.

In the first two years of the occupation, a very large share of these undocumented migrants appear to have been Korean residents in Japan who had been repatriated to, or made a visit to, Korea after the end of the war, and were now trying to re-enter Japan. As time went on, however, the motives for entry became more diverse. With Korea sliding towards civil war, a growing number of people fled to Japan to escape political persecution or economic and social disruption at home. A large number of migrants came from the southern Korean island of Jeju, which had particularly close social and economic connections with western Japan. After an abortive uprising against the Korean government in April 1948, the island was plunged into prolonged and bloody conflict in which tens of thousands of people were killed. The great majority of the “illegal entrants” arrested in western Shikoku in October 1948, for example, came from Jeju. The police report on the interviews with those arrested made the following analysis of the migrants’ main reasons for entering Japan: 40% came to join relatives already in Japan; 16% to “escape unsettled conditions in their own country”; 10% to escape bad economic conditions; 11% because they were invited by friends or others; 8% because of better working conditions in Japan; 4% in order to study and 11% for other reasons.[35]

Some brief but vivid insights into the migrant experience during these years come from the mass of private correspondence opened and read by SCAP officials during the occupation. According to John Dower, SCAP’s Civil Censorship Detachment, in the course of its four-year existence, “spot-checked an astonishing 330 million pieces of mail and monitored some 800,000 private phone conversations”.[36] Amongst these were many letters sent between Korea and Japan. The authorities assiduously translated and recorded passages which they believed contained evidence of illegal entry, smuggling, or the unauthorized remission of money to Korea, before (in most cases) re-sealing the letters and forwarding them to the unsuspecting addressees. The censorship records therefore contain some of the very few available traces of the voices of occupation-period undocumented migrants. But these are stolen voices – words never meant for public consumption, which the historian sees (as it were) only by looking over the shoulder of the anonymous censors as they pursue their shadowy trade. I quote them hesitantly and selectively. Much of the historical archive is produced by police, migration officials and others who viewed undocumented entrants as a menace or a nuisance to be controlled, suppressed and excluded. These ordinary everyday voices of the migrant experience, by contrast, can speak to the present-day in a way which, I hope and believe, may help to redress, rather than to compound, intrusive and dehumanizing process through which they were recorded.

Most of the extracts preserved in the SCAP archive are quite brief. They offer glimpses of connections to a network of friends and relatives in Japan, of determination to earn money or to obtain an education: “I landed in Kyushu on 30 August, two days after my embarkation from Masan. Now I am staying at Mr. A’s… If I get money here, I will return to Korea by October, but, if I cannot get it, I must put off my departure by two or three months.” “Though it was risky on the sea, I arrived safely in Japan by a secret ship the other day. I will return home to South Korea by the end of the year after finishing my business here. So I hope you will take care of my children during my absence.” “It was risky indeed to enter Japan by a secret ship, but I did it at the risk of my life, keeping it secret from my parents in South Korea. I will study hard at school here”. “I took a ship from Busan and reached Hakata. On board the ship, I had a very hard time because I had no money. Although I have been living in E. for about two months, I came to Osaka and entered the training school for technicians. Now I am living in a dormitory of the school. Until I succeed, I will never return home. After graduation, I will enter some training college.”

Many letters indicate how remittances from migrants were used to help support families in Korea: “as to the money you sent to aunt on 5 July 1949, uncle bought a paddy field with part of it”; “my father bought a paddy field for you and even completed the registration of it with the money you sent here”. They also speak eloquently of the hardship faced by undocumented migrants who, without official Alien Registration cards, were unable to obtain rations, medical care or basic services: “Since my arrival in Japan I have been staying at X’s… I have no prospect of returning for the time being. I am now in distress as I have no winter clothes, ration certificate, Foreign National [ie. Alien Registration] certificate. If there is any means of coping with my difficulties, please let me know”; “I failed in my business at Y, Korea, so I came to Japan by smuggling ship, but I cannot find a job here and am at a loss to know how to make a living. I regret that I came to Japan. Please send me some traveling expenses. I shall return to Korea”.[37]

Migration in the High Growth Years

As the records make clear, the cross-border movement was two-way: many migrants came for relatively short periods, to earn money, study or rejoin relatives. Some crossed back and forth between Korea and Japan many times. In her detailed study of the Jeju Islander community in Japan, for example, Koh Sunhui recounts the story of a man who was born in Osaka in 1943 and taken back to Jeju as a small child in 1946. In 1963, he tried to re-enter Japan to see his mother and other family members who had remained there, but was arrested as an illegal immigrant and forcibly returned to Korea. In 1964 he tried again, and managed to enter Japan, where he married a fellow immigrant from Jeju. However, in 1971, his illegal status was discovered and he was arrested, interned and deported, although his wife and children (who had voluntarily given themselves up to the migration authorities) remained in Japan. The family was thus broken up and his wife disappeared. In 1976, he again entered Japan illegally to look for his wife and managed to find her. However, it proved impossible to restore their relationship, and his wife later voluntarily returned to Korea. In the late 1970s he remarried in Japan to another woman from Jeju, and they had a child. A few years later their small child was injured in a fall, and when they sought medical treatment for the child, the father’s “illegal” status was discovered and he was arrested. He was again deported to Korea. However, with the support of local residents in the Osaka community where he had lived, and because his second wife had Treaty Permanent Resident rights (discussed below), he was finally able to obtain a resident’s visa and return to Japan legally in 1987.[38]

Such post-Occupation border-crossings, however, are particularly difficult to document because, by contrast with the disconcerting abundance of information contained in the SCAP records, Japanese government official records contain very little publicly available data on the topic. The issue of the treatment of Korean and Taiwanese residents in Japan, and particularly of postwar “stowaways”, clearly caused the government some embarrassment. The status of all Korean former colonial subjects living in Japan remained insecure until 1965, when Japan signed a treaty normalizing its relations with the Republic of Korea. Under the terms of the treaty, colonial-period Korean migrants to Japan (and their descendants) were offered special status as “Treaty Permanent Residents” [Kyôtei Eijûsha].[39] This status provided a greater measure of security than normal permanent residence status and enabled them to re-enter Japan after traveling or studying abroad. It also made it possible (for the first time) for family members to visit them in Japan, and generally provided protection from deportation except for those found guilty of serious offences.[40]

However, “Treaty Permanent Residents” did not receive access to welfare, public housing etc.[41] More importantly, individuals had to apply to become “Treaty Permanent Residents”, and could acquire this status only if they were South Korean citizens. The new system therefore excluded large numbers of Koreans in Japan who continued to identify themselves with the North Korean regime, or who chose to define themselves as nationals of “Korea as a whole” rather than of South Korea, and who remained stateless.[42] The Treaty also did nothing to help the many Korean residents who had “illegally” entered or re-entered Japan in the postwar period: indeed the agreement specified that the only people eligible to apply for Treaty Permanent Residence were those who “have lived in Japan permanently from before 15 August 1945 to the date of their application.”[43] The Japanese government seems implicitly to have acknowledged the injustice which this did, particularly to those who had been transformed into “illegal migrants” because they had traveled to Korea during the chaotic period of the early occupation. In June 1965, at the time of the signing of the normalization treaty with South Korea, it announced its intention to make “special provision” for Koreans who had entered Japan between 1945 and 1952.[44] However, perhaps because border-crossers were still associated in the official mind with fears of subversion, the agreement ultimately negotiated between the Japanese government and the Park Chung-Hee regime in South Korea was cautious and ambiguous, merely stating that Japan would “accelerate the processing of regular permanence resident permission for postwar entrants to Japan”.[45]

The numbers of such undocumented “postwar entrants” remains a matter for speculation. The published figures of arrests and deportations of “illegal entrants” from 1952 onward are low. Between 1952 and 1974, there were 31,622 arrests for illegal entry to Japan, an average of around 1,400 per year, with the number generally falling during the 1960s, but rising again slightly in the early 1970s (see Table 1). Even government officials, however, acknowledge that the actual numbers entering the country were much higher. According to an article published in the Asahi newspaper in 1959, the Japanese Immigration Bureau unofficially estimated the number of undocumented migrants from Korea living in Japan in the late 1950s at 50,000 to 60,000, while the police estimate was almost 200,000.[46] A 1975 Japanese Immigration Bureau report on migration controls, which contains an unusually frank discussion of “illegal entry”, noted that, although reliable statistics were unavailable, “tens of thousands” of undocumented migrants were believed to be living “secret lives” in Japan, most in the Osaka and Tokyo/Yokohama regions.

The report stated that “illegal immigration” had soared in the period from 1945 to 1955, stabilized in the late 1950s and started to decline gradually in the first half of the 1960s. After the normalization of relations with South Korea in 1965, as legal entry to Japan became easier, there had been a further decline in undocumented migration. However, “just in the last two or three years there have been striking cases like the apprehension at sea of one boat carrying 50 stowaways. If we consider these together with the results of investigations of illegal migrants [senzai mikkôsha] and of various other studies, we can assume that now as before a substantial number of stowaways are slipping through the hands of the investigating authorities and entering the country in secret.” [47]

The same point was re-emphasised by Sakanaka Hidenori, a Ministry of Justice official who has played an important role in shaping Japan’s migration policies. Writing in the second half of the 1970s, Sakanaka noted that “despite the considerable energies devoted to controlling illegal immigration to date, today there are said to be tens of thousands of illegal immigrants living in secret, and furthermore illegal immigrants continue unceasingly to arrive, particularly from Korea. Since we are surrounded by sea, have a long coastline and many ports, and have an inadequate number of immigration control officials, our capacity to apprehend illegal immigrants at sea can not be described as satisfactory, and the vast majority of them join the pool of illegal immigrants living in secret in our national society.”[48] Taniguchi Tomohiko, one of the few independent researchers to examine the issue during the 1970s, tried to follow up these published claims by interviewing immigration bureau officials. Although he failed to obtain any more detailed figures, he argued that the references to “tens of thousands” of illegal migrants was probably a bureaucratic underestimate, and that the real figure was more likely to be around 100,000.[49]

Both the 1975 report and the Ministry of Justice’s Sakanaka Hidenori point to a gradual shift in the motives for migration. In the early 1950s, family connections to Japan and the impact of the Korean War were major factors. The Korean War stimulated an economic boom in Japan, further widening wealth gaps between the two countries. From the late 1950s onward, therefore, the search for better-paid employment became an increasingly important reason for undocumented entry to Japan. For migrants from Jeju and other parts of the far south of Korea, after all, Japanese cities like Osaka were nearer than Seoul, and it was likely that many migrants had closer networks of relatives and friends in Osaka than they did in the Korean capital.[50] By the mid-1970s, Sakanaka claimed, over 80% of undocumented migrants were coming to Japan for employment purposes[51], though such stark figures probably do little justice to the complex motivations involved in the risky decision to migrate to Japan.

The great majority of “illegal migrants” were said to be “stowaways” who came on cargo vessels or fishing boats from Korea, often paying brokers hundreds of thousands of yen for the journey.[52] According to the Migration Control Bureau, the border crossings were generally run by “people smugglers” based in points of departure such as the Korean port of Busan. “Some of [the organizers] are men, but in many cases it is middle-aged women who act as the main intermediaries in people-smuggling, making contact with people who want to enter our country in secret. After an agreement has been reached, these women, together with the ship’s crew, conduct the stowaways to the people-smuggling boat.” Once in Japan, the Bureau noted, the migrants tended to find work in very small firms (often with less than five employees) producing such things as plastic goods, slippers, machine parts, plate metal and vinyl. A 1974 survey of 279 “illegal migrants” who gave themselves up to the Osaka migration authorities found that 70% had lived in Japan for between 15 and 20 years and most had very low incomes, although a handful were relatively wealthy people with assets of over 100 million yen. [53]

Special Permission to Stay

One of the striking points to emerge from the data given in the 1975 report is the fact that a large proportion (around one-third) of “illegal migrants” apprehended by the authorities were actually people who handed themselves in to police or the Immigration Control Bureau.[54] This fact sheds important light both on Japan’s postwar border control system, and on the likely scale of undocumented migration to Japan during this period. Studies like Taniguchi’s make it clear that Japanese immigration officials and police exercised very wide-ranging discretion in their dealings with undocumented migrants. Many cases of suspected “illegal entry” brought to the notice of the authorities did not result in arrests.[55] Besides, Japan’s immigration law contains a clause enabling the Minister of Justice to grant discretionary “special permission to stay” [zairyû tokubetsu kyoka] to deserving cases. “Illegal migrants” who voluntarily reported to the authorities were often hoping to obtain such “special permission”. According to the Immigration Control Bureau’s figures, in all 27,563 “illegal immigrants”, and a further 12,218 foreigners convicted of criminal offences, succeeded in obtaining such “special permission” between 1956 and 1979, with the figures peaking in the early 1960s and falling thereafter.[56]

Extensive administrative discretion was indeed a key feature of Japan’s postwar border control system, and was in part a legacy of occupation policy. In the final years of the occupation, SCAP had gradually transferred immigration control functions to a Migration Control Bureau[57] attached to the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs. In 1951 they also brought to Japan a retired senior official of the US Immigration and Naturalization Service, Nicholas D. Collaer, who advised on the drawing up of Japan’s postwar migration law. The resulting Migration Control Ordinance of October 1951 (renamed the Migration Control Law after the end of the occupation) reflected Collaer’s intense concerns about the “subversive” potential of immigrants at a time of rising Cold War tensions. The law gave the authorities sweeping powers to deport, not only illegal migrants and those with criminal convictions, but also any foreign resident who suffered from leprosy or had been admitted to a mental hospital, as well as those whose “life has become a burden to the state or local authorities by reason of poverty, vagrancy or physical handicap” and anyone “determined by the Minister of Justice to be performing acts injurious to the interests and public order of the Japanese nation”.[58] In practice, it seems that provisions for deporting the destitute or mentally and physically ill were hardly ever applied to Koreans in Japan, but the very existence of these legal provisions must surely have increased the sense of uncertainty which surrounded the lives of Zainichi Koreans.

Soon after the end of the occupation, in August 1952, migration control functions were transferred from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to an Immigration Control Bureau [Nyûkoku Kanrikyoku] located within the Ministry of Justice. The Bureau had branches in all major cities and at key entry points to Japan, and was also responsible for the running of Japan’s migrant detention camps. Immigration Control Officers [Nyûkan Keibikan] worked closely with the coastguard, police, and the local officials responsible for implementing the Alien Registration system. [59] All local government officials were supposed to report anyone whom they suspected of being an illegal immigrant, and members of the public were offered a 50,000 yen reward for reporting people who were found to be liable for deportation.[60] The immigration authorities also repeatedly conducted campaigns in coastal areas, mobilizing the local population to be on the watch for suspicious strangers.[61]

More broadly, Japan’s postwar migration system can be seen as encompassing a range of other individuals and groups: courts and lawyers who were responsible for handling disputed cases; community groups like the South Korean affiliated League of Korean Residents in Japan (commonly known by its abbreviation Mindan) and the North Korean affiliated General Association of Korean Residents in Japan (commonly known as Sôren in Japanese or Chongryun in Korean), who intermittently lobbied for migrants’ rights and took up the cases of individual members; and NGOs such as the Japan Red Cross Society and the International Committee of the Red Cross. The last two bodies worked to improve the conditions of detained “illegal” migrants, but the Japan Red Cross Society also played a central, complex and morally questionable role in the mass return of Korean residents to North Korea (discussed below).[62]

The postwar migration control system combined comprehensive controls with great discretionary power, which allowed authorities to deport anyone they considered “undesirable”, while taking a more “benign” approach to others. It is important to emphasise that the discretionary power given to the state to determine individual cases was not unique to Japan. Similar discretion was built into the Cold War era immigration laws introduced in a number of countries, including the United States. Indeed, Nicholas Collaer’s influence ensured that many aspect of Japan’s Migration Control ordinance resembled the 1952 US Immigraiton and Naturalization Law (more commonly known as the McCarran-Walter Act), an early draft of which was being debated by Congress while Collaer was in Japan. What was distinctive about the Japanese system was not so much the Migration Control Ordinance itself, but rather the way in which migration controls and citizenship policy interacted. The restrictive features of the ordinance were magnified by the presence of large groups of people who had been Japanese nationals when the ordinance was introduced but were unilaterally defined by the state as “foreigners” soon after.

When former colonial subjects were stripped of their Japanese nationality at the end of the occupation, the Japanese government hastily issued “Law no. 126”, stating that Koreans and Taiwanese who had entered Japan before the start of the Allied Occupation would be “allowed to remain in Japan, even though they still had no official residence status, until such time as their residence status and period of residence has been determined”[63]. In effect, this situation left the authorities free to choose which clauses of the Immigration Control Law they would apply to Koreans and Taiwanese in Japan, and which they would not.

The resulting system was highly arbitrary: official responses to undocumented migrants varied, both from individual to individual and from one immigration office to another. As an official who served in the Immigration Control Bureau during its first years later recalled, “in those days I think the Bureau lacked the actual capacity to carry out thorough investigations. Treatment of people varied hugely. For example, Yokohama and Tokyo were said to be lenient in giving people residence permission, but Nagoya and Kansai were said to be relatively strict.” The official went on to suggest that although regulations later became more rigorous, in the early 1950s it was relatively easy “even for people who had smuggled themselves into the country” [mikkô shite kita mono demo] to obtain residence documents “just by completing and submitting some sort of questionnaire”.[64]

Even in the late 1950s and 1960s, when the bureaucracy of border controls was more firmly established, there is evidence of the exercise of wide discretion by officials. In 1962, for example, immigration control officials received 28,531 reports of suspected “unlawful” foreign residents. Of these 1,710 reports were found to be without foundation, and 4,853 were investigated further, ultimately resulting in deportation orders being issued in 589 cases. Of the rest, a small number of cases were dismissed after further investigation and some were referred to other departments, while over 70% of the total – 20,106 cases – are listed as “investigation stopped or given special treatment”.[65] “Special treatment” included some of the 2,500 cases where undocumented migrants were granted “special permission to stay”, but what happened in the remaining cases is unclear.

These intriguing figures suggest two important points. The first is the possibly substantial number of undocumented migrants in Japan. While some of the reports received by the police were probably mistaken or malicious, it is also likely that the actual number of undocumented migrants in Japan would have been several times the number reported to the authorities in any given year. The second point to note is that official diligence in pursuing investigations varied greatly from case to case, and that, as well as the official granting of “special permission to stay”, simply dropping an investigation in mid-stream, appears to have been a rather common practice.

Bureaucratic discretion is a double-edged sword. At times it was undoubtedly used to resolve cases of real personal hardship. The story recorded by Koh Sunhui of the thrice-deported migrant from Jeju is just one of those cases. As Koh notes, a heartening feature of such stories was the way in which friends, neighbours, employees and workmates – Japanese as well as Korean – sometimes rallied round to support undocumented migrants in their struggle to obtain “special permission to stay”. The material she collected in her research on Jeju migrants includes several examples of such grass-roots community support for individual immigrant families.

Typical of this support are letters addressed to the immigration authorities in 1984 by the neighbours and employer of a man who had been detained as an “illegal migrant”, and then temporarily released pending determination of his fate. The man, a farmer from Jeju, had entered Japan as an undocumented migrant in 1969, and now lived in Osaka with his wife and young daughter. He had joined a very small printing works as one of its three employees in 1979. The firm’s owner writes in his letter of testimony, “we start work at 8.30 am and finish at 5.15 pm, but X was always at work by 8.15 am, and did overtime every day until about 6.30pm. Moreover, in the five years he has worked here he never had a day’s sick leave, and of course was never absent without reason…It came as a bolt from the blue to hear that X had been detained. I want X to continue working for me, and have re-employed him since his release from detention.”[66] Occasionally, local people initiated public campaigns, involving petitions and rallies, on behalf of undocumented migrants threatened with deportation.

However, the complete absence of clear guidelines surrounding “special permission to stay” meant that the outcome of such campaigns was always uncertain, and must often have been influenced by the personal whims of the officials involved the case. Most of the immigration officials interviewed by Taniguchi in the 1970s insisted that requests for special permission were judged entirely on a “case-by-case” basis.[67] One official, though, observed that decisions were in practice influenced by “the extent to which [immigrants] have a fixed attachment to Japan: for example, whether or not they have blood relatives here”. [honpô e no teichakudo – tatoeba ketsuen no umu] [68]

Letters from migrants and their supporters appealing for special permission to stay often stress integration into the local community – the fact that undocumented migrants had lived in Japan for years, had children at local schools and were active in events like street-cleaning and crime prevention campaigns.[69] All of this suggests a perception that officials were likely to look more favourably on individual cases if they could be persuaded that the migrants were not only “good citizens” and model workers, but also highly assimilated into Japanese society. But assessments of such things as “degree of fixed attachment to Japan” were inevitably subjective, and the lack of transparent guidelines for obtaining permission to stay left many postwar migrants profoundly insecure.

Sakanaka Hidenori observed that “for illegal migrants, whether they are deported to their own country or are able to remain in Japan is an issue which determines the entire course of their lives. They therefore take desperate measures such as seeking to have influential power-brokers [yûryokusha] take up their cases in order to obtain the special permission to stay from the Minister of Justice.” This situation must have made some migrants highly vulnerable to pressure from the very authority figures whose help they sought. Besides, as Sakanaka observed, it might mean that “even though the period of their illegal entry and their family circumstances are almost identical, one foreigner may obtain special permission to stay because of lobbying by a member of parliament or other power-broker, while another foreigner is forcibly deported. If such things take place, it is obvious to everyone that this must cause the foreigners concerned, and citizens in general, to experience an almost irreparable loss of confidence in the migration control system”.[70]

Detention and Deportation

Yoon Hakjun fled from South Korea to Japan in 1953, during the political turmoil following the Korean War. He arrived on a five-ton fishing boat along with some 35 other “stowaways”. However, even before they could set foot on Japanese soil, their boat was stopped by the coastguard and they were arrested and taken to Karatsu in Kyushu for questioning. While they were being held on the second floor of the local coastguard headquarters, Yoon escaped by climbing out of a window and sliding down a roof to the ground. After his escape, he managed to make contact with members of the Korean community in Japan, who eventually helped him to obtain work in a pachinko parlour. He also succeeded in obtaining an Alien Registration Document under a false name. With this, he entered college in Tokyo, and later married and had a daughter.

Like many of the other tens of thousands of undocumented migrants in postwar Japan, however, Yoon lived in constant fear of discovery. As he later wrote, “I would want to run away the moment I saw the shape of a policeman, even in the distance, and I was startled even if I encountered the uniformed figure of a guard on a train.”[71] In the 1970s, after his daughter entered primary school, she began to question why her father had two names. Concerned at the prospect of raising a family under a false name, in July 1976 Yoon went to the immigration office in Tokyo’s Shinagawa Ward and handed himself in to the authorities. Eventually, after paying a 300,000 yen bond, Yoon was allowed to stay in Japan, and became one of the very few postwar “stowaways” to publish an account of his experience. Although he was one of the “lucky ones” who obtained permission to stay, Yoon’s account sheds important light on the fear of detention and deportation which haunted undocumented migrants.

Those who handed themselves in to the authorities were, like Yoon, questioned at length about their entry to Japan. Since this had often occurred many years earlier, it was not always easy to provide the information desired by immigration officers. While Yoon was detained, waiting for his wife to pay his 300,000 yen bond, his belongings, belt and tie were removed and he was thoroughly body-searched before being placed for observation in a holding pen surrounded by iron bars. It was, he observes wryly, “a most valuable experience”.[72]

For those who were unable to obtain permission to stay, this experience was just the beginning of a long odyssey. Official regulations stipulated that illegal migrants arrested by police could be held for between twelve and twenty-two days before being indicted. They were then to be brought to trial within a year. If found guilty, they might be sentenced to a maximum punishment of three years’ hard labour, though in practice sentences often seem to have been commuted. During or after these police proceedings, the Immigration Control Bureau conducted its own inquiries which consisted of a preliminary investigation, an oral hearing by a senior Immigration Control Officer and (in some cases) an appeal for clemency to the Minister of Justice. Those who were able and willing could take the option of speeding the process by paying for their own deportation. But those whose appeals for “special permission to stay” were rejected and who were unable or reluctant to pay for their own deportation would ultimately be transported by train, handcuffed and under heavy police guard[73], to the detention center where they might remain for weeks or (in some circumstances) for years, waiting to be included in one of the mass deportations organized by Japan’s Immigration Control Bureau.

Between October 1950 (when the Japanese government took control of deportations) and 1979, 45,210 foreigners were deported, of whom 33,598 were Korean and 4,516 were Chinese. Of these, 19,847 people (all Korean) were returned to South Korea as part of mass deportations.[74] The largest number were illegal migrants, although the figure also includes a number of people expelled after completing sentences for criminal offences.

The reasons for the heavy security surrounding deportees on their journey to detention were vividly explained by one official who worked as a detention center guard in the early 1950s: “the so-called ‘criminals’ had actually served their sentences, and the illegal immigrants – well, they hadn’t done anything so terrible. They were less trouble than ordinary criminal defendants or convicts. The real problem was something much more serious than that. If they were deported, their futures would be destroyed. It was better to commit a crime in Japan and serve two or three years in prison than to be deported. Or in some cases, though this wasn’t publicly discussed, they had committed political crimes or thought crimes. If they went back there [to South Korea], the approach of the Syngman Rhee regime, which was in power then, was to take a very tough line with political criminals or thought criminals. So there were many deportees who had deep inner feelings that we guards didn’t know about. Well, for some people it was better to die than to return…”[75]

Japan’s first postwar migrant detention centres were established in great haste by the allied occupation authorities, as they sought to clamp down on the surging return flow of migrants from Korea in 1946. The two main camps were at Senzaki in Yamaguchi Prefecture and at Hario near Sasebo, the latter being just part of a much larger centre which was also used to process Japanese being repatriated from the former empire. Conditions, particularly in the Senzaki camp, which was run by the British Commonwealth Occupation Force, soon became chaotic, as facilities were overwhelmed by an influx of “illegal migrants”. By the end of July 1946 the camp, designed to hold 400 detainees, contained 3,400, of whom 1000 were being held on a transport vessel in Senzaki harbour. Hygiene conditions had become appalling, and dozens of detainees contracted cholera.[76] Soon after, the Senzaki camp was closed and its inmates were moved to Hario, which was run by the US 8th Army.

In 1950, as SCAP transferred border control duties to the Japanese authorities, the running of Hario Detention Centre was handed over to the Japanese government, and in December of that year the camp was relocated to Omura, near Nagasaki.[77] A second detention centre was established in Yokohama, but the functions of the two camps were distinct: as an Immigration Control Bureau report states with startling candour, “while Omura Migrant Detention Centre was established for interning Korean deportees, Yokohama Migrant Detention Centre was set up to intern other (mostly European, American and Chinese) detainees.” After inspections by foreign consular officials, who complained that the its facilities were not up to international standards, the Yokohama camp was relocated to a new site in Kawasaki city, and housed in a “two storey steel-framed building with beds, a refectory, shower rooms, an infirmary and clinic etc.” thus becoming a “detention centre which would not cause embarrassment even before the eyes of international observers.”[78]

Not many international eyes, however, were directed at Omura. The handover of detention powers from the Occupation forces to the Japanese authorities took place in great haste and some confusion. Omura, a former naval airbase, was rapidly converted to house an influx of detainees. Since it was officially intended only as a temporary holding-place for people soon to be deported, facilities were initially basic. The camp, which was surrounded by a barbed-wire fence, had large common living and sleeping areas shared by all detainees – men and women, ex-convicts and undocumented migrants, adults and children. Some attempted to gain a small measure of privacy for themselves and their families by using blankets to create a curtain around their living space.[79] The detention centre guards had received little training, and their senior ranks were largely recruited from the “foreign service police” who had helped to maintain political order in China and other occupied territories during the war.[80] In the words of one Omura inmate, who fled to Japan after deserting from the South Korean army to avoid fighting in the Vietnam War, the camp’s atmosphere was permeated by “the dark shape of Japan’s past imperialism”.[81]

But the process of deporting Korean detainees from Omura proved more difficult than the authorities had anticipated. Until the normalization of relations in 1965, Japan and South Korea had no formal agreement about the treatment of Korean residents in Japan. In May 1952 the Japanese authorities attempted to deport 160 “illegal migrants” and 125 Koreans convicts from Omura to Busan in South Korea. However, the South Korean government refused to accept those with criminal convictions, claiming that they were the responsibility of the Japanese government. The Japanese side was left with no option but to ship them back to Omura. At this point protest demonstrations broke out, as the 125 detainees and their supporters demanded their release. These were, after all, people who had already completed their sentences in Japan. While it may have seemed acceptable to accommodate them in the detention centre while they awaited deportation, protestors argued that it was wholly unjust to return them to detention when there was no certainty when or if they could be deported.[82]

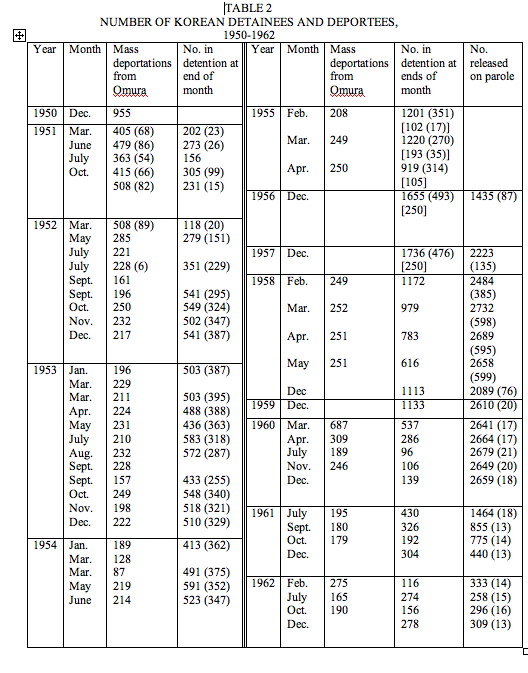

From 1952 on, therefore, Omura began to hold a growing number of Koreans who had served prison sentences and were now caught in a limbo between the policies of two governments, with no clear prospect of an end to their detention. Some ultimately spent as long as five years in Omura.[83] As the number detained grew, from 118 at the end of March 1952 to 549 at the end of October of the same year, authorities recognized the need to expand the camp. Between 1952 and 1953 Omura was extensively rebuilt: the old barracks were replaced by ten new buildings capable of housing a thousand people, and the barbed wire fence gave way to a five-meter high ferro-concrete wall. Worsening relations with South Korea, however, intensified the conflicts surrounding deportation. In the second half of 1954 and again in 1956 and 1957 Korea temporarily stopped accepting all deportees, including undocumented migrants. As a result, by December of 1957 the number in detention had soared to over 1,700, and some detainees were being held in a hastily-created overflow camp at Hamamatsu.[84] After a settlement with South Korea in 1960, which saw the Korean government agree to resume accepting deported “illegal immigrants” in return for a Japanese commitment to release many of the convict detainees “on parole”, numbers fell again. (See Table 2). However, by September 1970 22,663 people had spent time in Omura detention centre.[85] By 1965 sixteen babies had also been born there.[86]

Homusho Nyukoku Kanrikyoku ed., Shutsunyukoku Kanri to sono Jittai – Showa 39-nen, Tokyo, Okurasho Insatsukyoku, 1964, p. 114; figures outside brackets are totals; figures in round brackets ( ) are those with criminal convictions; figures in square brackets [ ] are those held in Hamamatsu.

The conflicts with South Korea over detainees also had another cause, reflecting the division of the Korean peninsula. Although the vast majority of Koreans in Japan came from the southern half of the peninsula, a substantial proportion chose to identify themselves with the North Korean regime, which many viewed as having greater political legitimacy than the US-backed Syngman Rhee regime and its successors, and which optimists of that period envisaged as offering a prospect of socialist equality and development. Omura detainees who were known opponents of the Syngman Rhee regime were terrified of deportation to South Korea, where they feared imprisonment or even execution, and some pleaded in great desperation to be deported to North Korea instead. This problem became connected with a wider movement, which emerged within the Korean community in 1958, for return to North Korea.

Though there can be no doubt that a considerable number of Koreans saw North Korea as offering an escape from the discrimination and legal uncertainties surrounding the position in Japan, recently declassified documents have shown that the Japanese government, working closely with the Japan Red Cross Society, covertly encouraged the return movement, which it saw as a means of reducing the size of an unwelcome ethnic minority. Between December 1959 and the end of 1961, 74,779 people (the vast majority ethnic Koreans, but also including several thousand Japanese spouses) left Japan for a new life in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, and the total number of those who had “returned” to North Korea by the end of the repatriation scheme in 1984 was over 93,000.[87] Among those who “returned” to the North were over 200 deportees from Omura.[88] From the late 1960s onwards, many of the “returnees” from Japan became the targets of political repression in North Korea. A considerable (though uncertain) number disappeared into labour camps or were executed.[89]

As struggles for the political allegiance of detainees raged within Omura, authorities tried to retain control by increasingly draconian regulation of the lives of its inmates. In many cases, this meant holding politically vocal detainees (particularly those identified as supporters of North Korea) in “protective custody” in Block 6, the camp’s isolation unit. A Korean student held in Omura in the 1960s, in a letter addressed to a Japanese university newspaper, described how one such detainee was held in isolation for over 150 days, unable to speak to fellow inmates and denied the right to leave Block 6 even for medical treatment in the camp clinic.[90]

Yoshitome Roju, a journalist who visited Omura three times between the 1950s and the 1970s, noted that, although the detention centre continued to be officially defined merely as a gathering place where people awaited deportation boats, not as a place of punishment, a significant transformation took place over time. While the solidity of the buildings and the range of facilities improved, “the realities of the detention camp became ever more prison-like”.[91] The concrete walls of Omura came to be plastered with a mass of rules and regulations which governed everyday life: everything from prohibitions on gambling and the use of matches or lighters to the instructions, “do not make unnecessary requests and demands to the authorities” and “unless you have received permission, it is forbidden to make contact, meet or have private conversations with inmates from other blocks.”[92]

In the enlarged and reconstructed camp, detainees were held ten to a cell, with a space equivalent to one tatami mat space per person. Describing the camp in the late 1960s, Itanuma Jiro reported that the cells, whose windows were heavily barred by metal grills, each contained a basic toilet and wash place, but that hot water was in short supply and available only for brief periods. Women and children were held separately from men: an arrangement which may have increased their security, but also resulted in the separation of families. Men were allowed to be reunited with their wives and children for approximately 30 minutes once every two weeks, during which time they were instructed to communicate in Japanese.[93] During the 1960s and 1970s, Omura Detention Centre was the subject of repeated complaints by human rights groups, who pointed to poor food standards, inadequate medical care and dehumanising treatment of detainees, and in 1969 the camp became the target of large demonstrations by Japanese student and peace groups.

Oguro Shuntaro, who was a guard at Omura in the 1950s, later recalled – apparently with amusement – a letter which had arrived at the camp during his time there. The writer, a Korean, had addressed the letter to “Omura Detention Centre” [Omura Shuyojo], but had inadvertently used the wrong characters to write the word Shuyojo, whose literal meaning translates roughly as “receiving and holding place”. On the envelope, the syllable shu was written with the character meaning “prisoner”, and the syllable yo with the character meaning “to rear animals”. Oguro adds, “It doesn’t seem that they were poking fun at us. Koreans actually gave [the centre] that name”.[94]

Enduring Legacies

Debates about “migrant labour” and “guest workers” are commonly based upon several assumptions. They assume that there is a firm line distinguishing “nationals” from “foreigners”; that there is a clear distinction between “legal” and “illegal” migration; and that political refugees and economically motivated “immigrant workers” can be unambiguously placed in separate categories. But in Japan’s postwar history, there were moments when each of these assumptions was destabilized.

Japan’s postwar migration control system was part of a wider world order. Like migration controls elsewhere, it was shaped by the concerns of the Cold War and, as we have seen, was strongly influenced by US models. However, the particular circumstances surrounding the transition from colonial empire to Cold War in East Asia resulted, in the Japanese case, in a migration control system with distinctive features, many of which survive to the present day. In this essay, I have sought to suggest that the distinctive features of the Japanese system were much less the products of a unique “Japanese culture” than they were of the specific historical and geopolitical circumstances in which Japan’s postwar immigration laws were framed.

During the occupation period, the treatment of former colonial subjects as “foreigners” was legally dubious, and the process by which returnees to Japan were transformed into “illegal immigrants” was highly arbitrary. These problems were compounded, rather than resolved, by the Japanese government’s post-Occupation decision unilaterally to revoke the Japanese nationality of Korean and Taiwanese former subjects, and to impose tight migration restrictions, which prevented family reunions. In practice, the very harshness of the official policy made it impossible for the letter of the law to be strictly enforced. Rounding up and removing every “illegal immigrant” who had crossed the border between Korea and Japan from 1946 onward would have been both extremely inhumane and utterly impractical. In tacit recognition of this fact, the Japanese authorities therefore developed a system where a highly restrictive official policy on immigration went hand in hand with a great deal of “administrative discretion”. Officials quietly accepted the presence of tens of thousands of undocumented migrants, and developed informal channels through which at least some could eventually acquire legal residence rights. In this way, the events of the postwar decades laid the basis for Japan’s contemporary “illegal immigration policy”: a policy under which official entry requirements remain highly restrictive, while the government selectively turns a blind eye to the entry of hundreds of thousands of “illegal migrants” whose presence serves economic or other purposes.

Post-1980 “illegal migrants” from Korea, China, Southeast Asia and elsewhere have followed paths blazed by the postwar “stowaways”, often finding employment in similar small factories producing metal goods, machine parts etc. [95] There is even evidence of a “globalization” of the very routes which brought undocumented migrants from South Korea to Japan in the 1950s and 1960s: today some Chinese, Iranian, South Asian and other migrants go first to Korea before crossing by boat from Busan to Japan.[96]

Meanwhile, though Omura remains in operation, it has become just a small element in a wider archipelago of detention centers. In June 2001, for example, 1262 people from a diverse range of countries were being held in Japan’s four main migrant detention centers: 453 in Tokyo; 302 in the Eastern Japan Migration Control Centre in Ushiki, Ibaraki Prefecture; 269 in Omura and 240 in the Western Japan Migration Control Centre in Osaka.[97] There were also smaller temporary detention centers such as Narita Airport’s controversial “Landing Prevention Facility”[98], while in 2003 the Migration Control Bureau opened a new and greatly enlarged detention center in Tokyo’s Minato Ward, capable of holding 800 people.[99]

During the 1950s and 1960s, the difficulties of enforcing Japan’s exclusionary immigration policies were compounded by the fact that considerable numbers of entrants from Korea were to all intents and purposes refugees as defined by the Geneva Convention of 1951. However, until 1967 the Convention did not cover events such as the Korean War and its political aftermath – it applied only to displacements caused by “events occurring before 1 January 1951” and its coverage was largely restricted to Europe. Besides Japan did not ratify the Convention until 1981. As a result these migrants were not officially acknowledged as refugees, and many joined the pool of labourers working for low wages in small firms. While circumstances in postwar Western Europe made it possible to maintain a (partly fictional) conceptual distinction between “migrant workers” and “refugees”, public discourse in postwar Japan melded all into the shadowy category labeled mikkôsha – “stowaways”. Today, as the circumstances of the post Cold War world again erode the political boundaries between “migrant worker” and “refugee” – and as recurrent panics over “people smuggling” become a worldwide political phenomenon – it is important to look back at Japan’s postwar experience and consider its lessons for the present.

“Bureaucratic discretion” may be used with compassion and imagination to mitigate human suffering. But the combination of a highly restrictive formal immigration policy with arbitrary and non-transparent “discretion” can also be a source of injustice, violence and (potentially) corruption. By the 1970s, some of those familiar with Japan’s migration control system were calling for reforms which would liberalize immigration law and offer a blanket amnesty to “stowaways” who had arrived before a certain date, while also making the guidelines surrounding the implementation of the law more transparent.[100] In spite of incremental reforms since 1981, however, the official framework of migration policy remains highly restrictive, while the day-to-day practice of border controls and the treatment of migrants remain realms of enormous discretion and considerable arbitrariness. More fundamental reform is a still unfulfilled task for the twenty-first century.