Robert Lang and the Global Reach of Origami

By Susan Orlean

One of the few Americans to see action during the Bug Wars of the nineteen-nineties was Robert J. Lang, a lanky Californian who was on the front lines throughout, from the battle of the Kabutomushi Beetle to the battle of the Menacing Mantis and the battle of the Long-Legged Wasp. Most combatants in the Bug Wars—which were, in fact, origami contests—were members of the Origami Detectives, a group of artists in

At the time, Lang was in his thirties. He had been doing origami—that is, shaping sheets of paper into figures, using no cutting and no glue—for twenty-five years and designing his own models for twenty. He has always considered himself very much a bug person, but his earliest designs were not insects; in the nineteen-seventies, he invented an origami Jimmy Carter, a Darth Vader, a nun, an inflatable bunny, and an Arnold the Pig. He would have liked to have folded insects, but, in those years, bugs, as well as crustaceans, were still an origami impossibility. This was because no one had yet solved the problem of how to fold paper into figures with fat bodies and skinny appendages, so that most origami figures, even television characters and heads of state, still had the same basic shape as the paper cranes of nineteenth-century Japan. Then a few people around the globe had the idea that paper folding, besides being a pleasant diversion, might also have properties that could be analyzed and codified. Some started to study paper folding mathematically; others, including Lang, began devising mathematical tools to help with designing, all of which enabled the development of increasingly complex folding techniques. In 1970, no one could figure out how to make a credible-looking origami spider, but soon folders could make not just spiders but spiders of any species, with any length of leg, and cicadas with wings, and sawyer beetles with horns. For centuries, origami patterns had at most thirty steps; now they could have hundreds. And as origami became more complex it also became more practical. Scientists began applying these folding techniques to anything—medical, electrical, optical, or nanotechnical devices, and even to strands of DNA—that had a fixed size and shape but needed to be packed tightly and in an orderly way. By the end of the Bug Wars, origami had completely changed, and so had Robert Lang. In 2001, he left his job—he was then at the fibre-optics company JDS Uniphase, in

Lang is accustomed to being surprising. Some years ago, he was the mystery guest on the television game show “Naruhodo! Za Warudo”—the Japanese version of “What’s My Line?”—and he amazed the audience and the contestants, because they couldn’t believe that an American could be an origami expert. People who know him as a scientist are flabbergasted when they hear that he is one of the world’s foremost paper-folding artists, and are often surprised that such a thing as a professional origami artist even exists. People expecting him to be kooky—or, at the very least, Japanese—find his academic accomplishments and his white male Americanness puzzling. Recently, he was commissioned by Lalique, the French crystal company, to demonstrate folding at a launch for its new collection of vases, which are rippled and creased in an origami-like way. The launch was at a Neiman Marcus in

“My God, look,” she said, pointing to Lang. “He’s in a suit!”

Lang stopped folding and looked up at her.

“It’s just . . . to see an artist all clean and dressed, and in a suit,” she sputtered.

Lang smiled and said, “Well, my kimono was at the cleaners.” He resumed folding.

“You’re good at the origami,” the woman said. “Have you done other jobs?”

Lang said, “Yes, in fact, I have. For years, I was a physicist.”

The woman grabbed her husband’s arm again and gasped, “Oh, my God!” While she was recovering, two men ambled up. “Do people, like, pay you?” one of them asked. Before Lang could answer, the other guy, brandishing a baby lamb chop, asked if he knew how to make the Statue of Liberty.

“Yes, I do,” Lang said. “I’m not going to make it right now, but I do know how to do it.” He put aside the piece he was working on, and took a new sheet of paper from the stack. He creased it, flipped the paper over, creased it again, lined up the edges, smoothed the sides together, pinched it here and there, and tugged on one edge. He did this with quick, meticulous movements, his hands crossing back and forth over the sheet as if they were tracing a melody. Suddenly, the sheet of paper crumpled and then opened into a shape—a tiny violinist, sawing away at a violin.

“That’s just crazy, man,” the guy holding the lamb chop said. “I mean, wow.”

Lang grew up outside

Lang went to college at Caltech, where he studied electrical engineering. “Caltech was very hard, very intense,” he told me recently. “So I did more origami. It was a release from the pressure of school. I’d fold things, record the design, and then throw the model away.” He had never met anyone else who did origami, and he didn’t tell people about his pastime. His wife, Diane, whom he met at Caltech when they both had roles in a campus production of “The Music Man,” remembers visiting his apartment in

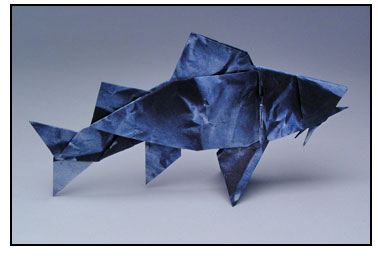

Lang kept folding while earning a master’s in electrical engineering at Stanford and a Ph.D. in applied physics at Caltech. As he worked on his dissertation—“Semiconductor Lasers: New Geometries and Spectral Properties”—he designed an origami hermit crab, a mouse in a mousetrap, an ant, a skunk, and more than fifty other pieces. They were dense and crisp and precise but also full of character: his mouse conveys something fundamentally mouse-ish, his ant has an essential ant-ness. His insects were especially beautiful. While in

The Japanese have been folding paper recreationally for at least four hundred years. For the first two hundred of those years, designs were limited to a few basic shapes: boxes, boats, hats, cranes. Folding a thousand cranes—all of white paper, which was the only kind then used—was thought to bring good luck. The principle was simple. The sheet of paper was the essence: no matter what shape it became, there was never more paper and never less; it remained the same sheet. Japanese folding probably didn’t spread directly to the West. There is no definitive history, although David Lister, a retired solicitor in

In 1837, a German educator, Friedrich Fröbel, introduced the radical idea of early-childhood education—kindergarten. The curriculum included three kinds of paper folding—“The Folds of Truth,” “The Folds of Life,” and “The Folds of Beauty”—to teach children principles of math and art. The kindergarten movement was embraced around the world, including in

In the mid-nineteen-forties, the American folklorist Gershon Legman began studying origami. Legman was a man of diverse inclinations: he collected vulgar limericks, wrote a book about oral techniques in sexual gratification, and is credited with having invented the vibrating dildo when he was only twenty. After becoming interested in origami, he made contact with paper-folders around the world—most significantly, Akira Yoshizawa, a Japanese prodigy who, before being recognized as an extraordinary talent, made a meagre living by selling fish appetizers door-to-door in

One clear, chilly day not long ago, I met Lang at Squid Labs, a high-tech research-and-development company headquartered in an enormous concrete building that used to be part of the Alameda Naval Air Station, near

Lang was, by all accounts, good at his science jobs: he wrote more than eighty technical papers and holds forty-six patents on lasers and optoelectronics. All the while, he was plotting how he would find time to write origami books. He published several while he was still in the laser world, starting with “The Complete Book of Origami,” in 1989, but he knew that it would require all his time to write the one he had in mind, which, instead of providing patterns for folders to follow—the typical origami book—would teach them how to design their own.

The bad luck of the dot-com bust turned out to be good timing for him. Beginning in 2000, JDS Uniphase, which supplied components to computer companies, lost much of its business, so Lang’s duties shifted from overseeing research and development to managing pay cuts and plant closings. “Laying people off was a lot less fun than inventing things,” he said. “There were plenty of people doing lasers. The things I could do in origami—if I didn’t do them, they wouldn’t get done. Deciding to leave was a convergence of what I wanted to do plus what was happening at my company.” Given his personality—composed, moderate, painstaking—it seems like an unimaginably audacious move. A lot of people, throughout history, have walked away from respectable careers to become, say, poets or jazz musicians, but there are viable markets, albeit small and competitive, for those pursuits. Becoming a professional paper-folder is chancier, since there is still no established market for origami as a collectible art form, and, until recently, it was not much promoted as one: Yoshizawa published books of his designs but never sold any of his pieces. I wondered if Lang’s family wanted to kill him when they heard of his career plans. What he did, after all, is analogous to, perhaps, quitting a job as a neurosurgeon to take a shot at becoming a professional knitter. Diane has said that even though the transition seems as if it should have been scary, it wasn’t. His parents were also sanguine. They’d had a somewhat similar experience when Lang’s sister, who had been studying for a master’s in microbiology, left her field to become an interior designer. Lang’s mother, Carolyn, recalls, “I think I jokingly said, ‘Are you going to be able to feed your family?’ But I know Robert, and I knew he would have had it all planned.”

The first part of his plan was to write the book he’d been contemplating while still at JDS Uniphase—“Origami Design Secrets,” which was published in 2003 and lays out the underlying principles of origami and design techniques. He then set to work full time on designing new models and refining his old ones. In truth, Lang is not entirely out of the science world: he was just named the editor-in-chief of the Journal of Quantum Electronics, published by the

Many of Lang’s commissions are less technical. He recently designed toilet-paper origami animals for a Febreze commercial, which were folded by a fellow origami artist, Linda Mihara, and last year, again assisted by Mihara, he created an origami world—forest, fields, deer, Victorian houses, a dragon—for a thirty-second Mitsubishi spot. He was hired to make a life-size Drew Carey for “The Drew Carey Show” and some airplane seats for the cover of Onboard, an aircraft-seating magazine, and to fold dollar bills into any shape he wanted (a birthday gift for a well-known fashion designer). He sells quite a few pieces to origami lovers—his most popular piece is a Hanji-paper bull moose, which is about nine inches tall and is available through his Web site for eight hundred dollars. Lang’s favorite commission was to fold an endangered Salt Creek tiger beetle for an entomologist who collects Salt Creek tiger beetle art. “For me, that commission was like manna from Heaven,” he said. “I’ll never be done with bugs.”

The laser cutter was growling away, scoring one of Lang’s Hanji sheets. He twiddled with his computer. On the screen was a lacy geometric pattern. Lang had designed it with software he started writing in 1990 called TreeMaker, which is well known in origami circles; it was the first software that would translate “tree” forms—that is, anything that sort of resembles a stick figure, such as people or bugs—into crease patterns. Another program he wrote, ReferenceFinder, converts the patterns into step-by-step folding instructions. This secured his position as the most technologically ambitious of the origami masters. In 2004, he was an artist-in-residence at M.I.T., and gave a now famous lecture about origami and its relationship to mathematical notions, like circle packing and tree theory. Brian Chan, a Ph.D. candidate in fluid dynamics at M.I.T., told me recently, “That was a huge lecture. It got everyone talking.” It inspired Chan to put his hobby of blacksmithing on hold and take up origami; he and Lang are now regular participants in an annual competition that is a friendly continuation of the Bug Wars. Last year’s theme was a sailing ship. Lang wasn’t happy with his entry—a sailboat with its sails down, revealing its skeletal masts—but talks enthusiastically about Chan’s. From a single sheet, Chan created a brig under full sail being attacked by a giant squid.

Something about origami’s simplicity and its apparently endless possibilities appeals to people. In 2003, the

A few months ago, I went to a meeting of the

Lang believes that there is still much more to do in origami. “It’s like math,” he said to me one day, as we were having lunch at a burger joint near his studio. “It’s just out there waiting to be discovered. The exciting stuff is the stuff where you don’t even know how to begin.” He wants to improve his human figures, work with curved folding, and keep refining his insects. He wants to fold a better mousetrap and a better mouse. His primary interest is in the art of origami, but he has great faith in its expanding practical potential—solar sails, air bags, containers, shelters, medical implants. He had a recent message on his voice mail from someone who wanted to discuss using origami in the manufacture of plastics. We were about to leave the restaurant and head back to his studio. Before we left, I couldn’t help but ask him to do something pretty with his placemat. It was just a flimsy rectangle and had a few grease spots from his sandwich, but he flipped it and folded it and did some magic, and left the waitress with a perfect white boat.

Susan Orlean is the author most recently of My Kind of Place: Travel Stories from a Woman Who’s Been Everywhere.

This article appeared in The New Yorker,