Peter J. Katzenstein

A succession of weak Japanese Prime Ministers, the drama of the war in Iraq and Afghanistan, and the current global financial crisis once again have returned the subject of Japanese security policy to a position of relative political marginality. [*] Throughout the Cold War, the analysis of Japanese security was a topic largely overlooked by both American students of Japan and by students of national security. Japan, after all, was the country that had adopted a Peace Constitution with its famous Article 9 interpreted as legally banning the use of armed force in the defense of national objectives. Its professional military had little public standing and was under the thumb of civilians. And Japan’s grand strategy aimed at gaining power and prestige and sought to leverage its economic prowess to a position of regional and perhaps global leadership that would complement rather than rival that of the United States. At the same time Japan relied on the continued protection by the U.S. military. To be sure, since the late 1970s the U.S. government persistently pressed Japan to play a larger regional role in Asia and to spend more of its rapidly growing GDP on national defense. But Japan made no more than marginal concessions. On security issues it kept a low regional profile, and since the late 1980s Japanese defense spending consistently stayed below one percent of GDP. Writing on problems of Japanese national security, thus, was left to policy specialists issuing regular conference reports on the ups and downs of the U.S.–Japan bilateral defense relationship. Theoretically informed scholarship was conspicuous by its absence.

Things have changed a great deal. The end of the Cold War, the collapse of the Soviet Union, and the 9/11 attacks have fundamentally transformed the international landscape. Having failed in understanding the political dynamics that led to the end of the Cold War, some specialists of national and international security turned their attention from the Western to the Eastern perimeter of the Euro–Asian land mass. Would not the rapid rise of Japan, South Korea and Taiwan, the Newly Industrializing Economies in Southeast Asia, China and Vietnam, yield fertile grounds for the application of the timeless truths of realist theory? As peace was breaking out in Europe, was Asia not destined to prepare for war (Friedberg 1993/94)?

Yet war and ethnic cleansing returned to Europe in the 1990s, while Asia remained peaceful. Thought to be unstoppable in the 1980s, Japan’s economic juggernaut foundered on more than a decade of economic stagnation from 1990, while China’s economy continued to grow annually by about 8–10 percent, creating new security dynamics in East Asia as well as between East Asia and the United States. The Asian financial crisis of 1997 illustrated how closely Asia’s economic miracle had become linked to regional and global markets. It also showed how, with the exception of Indonesia, Asian leaders skillfully maneuvered out of that crisis in a very short time. The attack of September 11 and the U.S. global war on terror increased regional concerns about the rise of al Qaeda (Chow 2005; Leheny 2005). More importantly, it elevated the political importance of North Korea as a member of what President Bush called “the axis of evil,” comprising countries that were suspected of trading in the illicit international market for nuclear technology and thus enhancing the risk that weapons of mass destruction could end up in the hands of groups intent on large-scale violence, or otherwise engaging in criminal or terrorist activities.

JAPAN IN THE AMERICAN IMPERIUM

The broader context in which Japanese and Asian security affairs play themselves out continues to be shaped heavily by the United States as the preeminent actor in the international system and in East Asia. For better and for worse, since the 1930s American policies have had an enormous impact on East Asia. The creation of a liberal international economic order after 1945 was an important precondition for the export-oriented economic miracles of East Asian states. And the permanent stationing of about 100,000 U.S. troops in Japan and South Korea guaranteed continued U. S. political involvement. The Korean and Vietnam wars killed millions of Koreans and Vietnamese and left divisive historical legacies, especially on the Korean peninsula. It would be a mistake, however, to equate the United States government solely with its economic, diplomatic or military policies. The United States is both an actor in and a part of an American system of rule in world politics that has evolved over the last half century. The concept of imperium refers to both actor and system, to the conjoining of power that has both territorial and non-territorial dimensions (Katzenstein 2005).

The American Imperium [1]

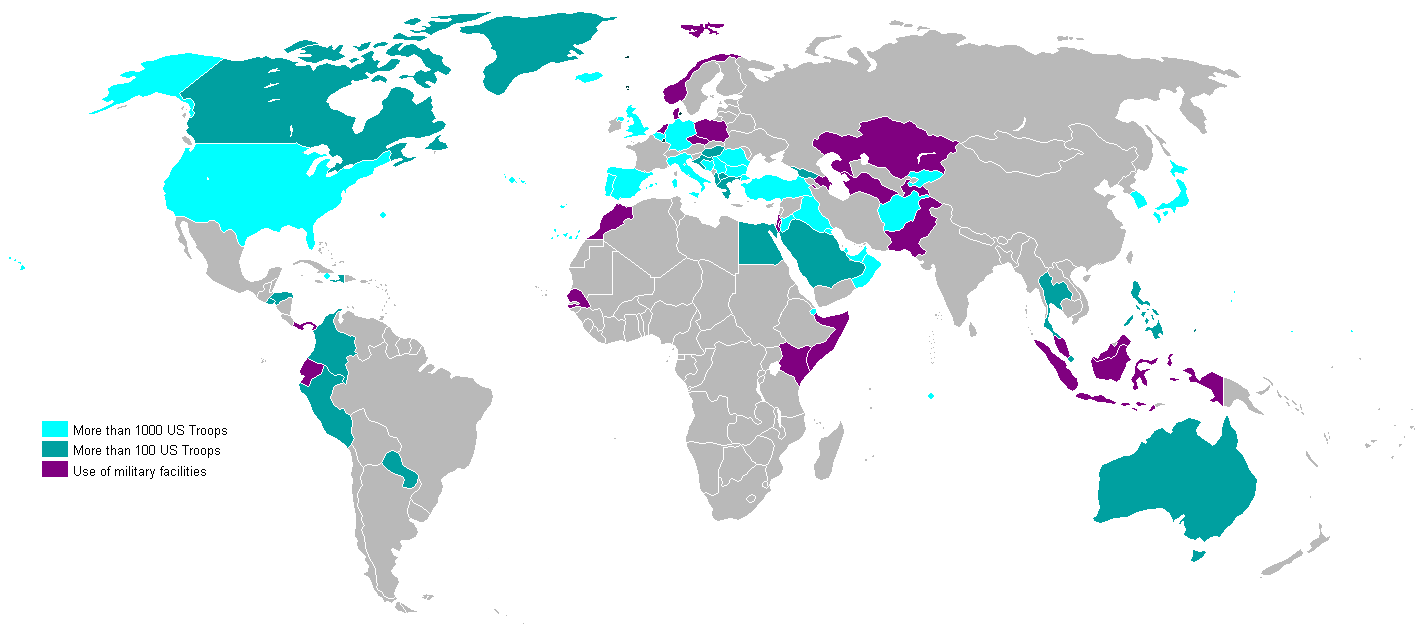

The United States government deploys its power in a system of rule that merges the military, economic, political and cultural elements which constitute the foundations for the preeminence of the American imperium in world politics. Territorial power was the coinage of the old land and maritime empires that collapsed at the end of the three great wars of the 20th century: World War I, World War II and the Cold War. American bases circling the Soviet Union during the Cold War and springing up again after the 9/11 attacks underline the continued importance of the territorial dimensions of the American empire. The U.S. has a quarter of a million military personnel deployed on scores of large military bases and hundreds of small ones scattered around the globe. The non-territorial dimensions of American power are reflected in the American Empire, a constellation of flexible hierarchies, fluid identities, and multiple exchanges. It is defined by technologies which are shrinking time and space, the alluring power that inheres in the American pattern of mass consumption, and the attraction of the American dream in a land that, evidence to the contrary notwithstanding, is viewed by many millions around the world mainly as the promised land of freedom and unlimited possibilities.

US military bases worldwide, 2007. Wikimedia

US military bases worldwide, 2007. Wikimedia

Territorial empire and non-territorial Empire are ideal types. They merge in the political experience and practices of the American imperium and the formal and informal political systems of rule as well as the combination of hierarchical and egalitarian political relations that it embodies. This imperium is both constraining and enabling. The relative importance of its territorial and non-territorial dimensions waxes and wanes over time, shaped by the domestic struggles in American politics that reflect the rise and fall of political coalitions with competing political constituencies, interests and visions. Japanese and Asian security affairs are encompassed by an imperium which embodies both the material, territorial and actor-centric dimensions of U.S. power on the one hand and the symbolic, non-territorial and systemic dimensions of American power on the other.

Regional core states such as Japan and Germany play crucial roles in linking world regions such as Asia and Europe to the American imperium. Specialists focusing on the politics of regional powers other than Japan and Germany—such as China, Korea, Britain or France—may rightly object to the singling out of Germany and Japan as special core states. Yet, core states play different roles, as supporter states in the case of Japan and Germany, and as regional pivots in the case of, for example, China and France (Chase, Hill and Kennedy 1999). The distinction between pivot and supporter is a historically specific rather than a structurally general argument. It identifies Japan and Germany as core states not because of their size and power but because of their specific historical experience and evolution in the Anglo-American imperium. And because the imperium is Anglo-American, for both structural and historical reasons Britain — with its “special relationship” to the United States and for many decades wracked by fundamental disagreements about its European role — cannot play the role of supporter state.

A historical comparison of Japan with Germany has advantages over the narrower conceptualization that Richard Samuels (2007) has offered in his recent book. Samuel’s account is a triumph of “old” security studies over “new” security issues such as human security, environmental degradation, terrorism or the spread of weapons of mass destruction. It is striking how the discursive moves of the main-stream and anti-mainstream in Japan’s multiple strategic traditions so carefully tracked in his book are remarkably narrow in what they have to say about the full range of Japan’s contemporary security challenges. Equally significant, Samuels rigorously sidesteps all opportunities to place Japan in a comparative perspective. The attentive reader thus is left with an analysis that makes Japan look unique rather than distinctive. Japan’s self-defined sense of vulnerability is a subject that looms large for Samuels. Yet this condition is hardly unique to Japan. Stubbs (1999, 2005), Zhu (2000, 2002), and Larsson (2007) have applied the same concept to explain a variety of political outcomes in Asia, and I have tried to do the same for the small European states (Katzenstein 1985). Is there some distinctive quality to the experience of vulnerability that sets Japan apart from other states? Furthermore, in contrast to Germany with its important role in NATO and the EU, Japan, the other main Axis power that suffered total defeat in its challenge of Anglo-American hegemony in the middle of the 20th century, has resisted firmly the internationalization of its state identity and security practices (Buruma 1994; Nabers 2006). Is there a relation between the experience of vulnerability and the resistance of internationalization? And if there is, what is its nature? Answers to such questions are important. Neglecting comparisons makes Samuels’s core claim—that Japan is currently in the process of articulating a new grand strategy involving various forms of hedging—empirically indistinguishable from that of its main rival: that Japan is currently in the process of refurbishing its existing grand strategy. One of the great virtues of the book, however, is the fact that repeatedly the author graciously concedes this central point (Samuels 2007: 64, 107–08, 209. See also Pyle 2007; Midford 2006; Mochizuki 2004).

Because only Japan and Germany challenged in war the Anglo-American world order in the first half of the 20th century, and experienced traumatic defeat and occupation, no other world region has evolved similarly situated core states. After its historic victory over the political alternative that Fascism posed to Anglo-American hegemony in the middle of the 20th century, U.S. foreign policies sought to anchor its Japanese and German clients firmly within America’s emerging imperium ( Lake 1988).

Gavan McCormack (2007, 79–80) writes: “…it is hard to escape the feeling that they [U.S. officials today] functioned rather as proconsuls, advising and instructing, while seeing Japan still as an imperial dependency, rather like General MacArthur a half-century earlier, who was acclaimed a benevolent liberator even while treating the Japanese people as children.” An assessment that was correct for the late 1940s is wrong half a century later. In the case of Japan as much as Germany it is a mistake to argue that this client status remains intact. Eventually both states left their client status behind, becoming regional powers in their own right and supporters of the United States. Each is intent on exercising economic and political power indirectly, thereby simultaneously extending the reach and durability of the American imperium (Katzenstein and Shiraishi 1997, 2006; Katzenstein 1997). These two supporter states were of vital importance in keeping Asia and Europe porous rather than closed regions. Their attachment to the American imperium was steady, first in the name of anti-Communism, and subsequently in the name of globalization and counter-terrorism. Yet the difference in the geo-strategic context—as yet no politically viable East Asian Community, no large immigrant Muslim population in Japan, a geographically proximate perceived national security threat in the form of North Korea, and a deep suspicion of an increasingly powerful China—has left Japan a more dependable supporter state of the United States than Germany. The bipartisan Armitage-Nye report of October 2000 illustrates how far American policy has come to recognize Japan’s strategic importance for U.S. foreign policy in East Asia, and how far it has left behind policies that regarded Japan as a client (as in the 1950s) or the subject of external pressure politics (as in the 1980s) (Green 2007: 147).

This is not to deny that as history changes, so may the character and standing of these two supporter states. Japan and Germany are increasingly removed in time, although not necessarily in terms of their memory, from their traumatic national defeats. After 9/11 the Bush administration’s sharp turn toward a militant and unilateralist policy has given rise to strong opposition among mass publics abroad (Katzenstein and Keohane 2007). For example, democratization in South Korean politics gave rise to an anti-Americanism that has been accentuated greatly by the abrasive political style of a hapless U.S. diplomacy (Steinberg 2005). Anti-Americanism among the young in particular has risen to heights that would have been inconceivable in the late 1990s. In China, American-inflected globalization is embraced while anti-hegemonism, especially its behavioral manifestations, continues to be a powerful oppositional ideology that resists American primacy. While it is not as virulent or racist as anti-Japanese sentiments, this anti-Americanism is a powerful latent force that is readily activated around many issues and most certainly around the volatile issue of Taiwan (Johnston and Stockmann 2007).

Japan is a notable exception to these changes in East Asian popular attitudes. In the mid- and late 1950s Japanese anti-Americanism ran so deep, in the form of opposition to the US-Japan Security Treaty, that President Eisenhower cancelled his visit in 1960, after the Japanese government informed the White House that a full mobilization of Japan’s total police force could not guarantee the physical security of the Presidential motorcade from Haneda airport to the Imperial Hotel in downtown Tokyo. Since the end of the Vietnam war anti-Americanism has virtually disappeared as Japan’s party system has moved to center-right, and as a new national consciousness has taken hold of a younger generation psychologically no longer moved by the dominant concerns of the 1950s and 1960s and unnerved by North Korean nuclear-reinforced bluster and China’s rise. At a popular level the relationship between Japan and the United States is free from rancor. Despite sustained protests against American bases in Okinawa, public opinion polls typically show above 60 per cent of the Japanese public favoring the United States, about twice as large as corresponding numbers for various European countries (Pew Global Attitudes Project 2007; Tanaka 2007).

Furthermore, as the character of the American imperium changes, its two supporter states are unavoidably repositioned in the matrix of Asian and European politics. There exists thus no reason why the role of these supporter states could not be filled by others. If Germany were to be submerged totally in a European polity (which seems very unlikely) and if Japan’s GDP were surpassed, eventually, by China’s (which seems very likely, but not imminent), together with other historical changes affecting Asia, Europe, and the United States, this might eventually transform the role played by traditional supporters and other regional pivots. In the case of France and China, for example, the magnitude of such changes would have to be very substantial. These two states are crucial pivots. But it is hard to imagine how they could replace Japan and Germany any time soon as Asia’s and Europe’s supporter states.

Japan

Alliance with the United States has provided the political and strategic foundations for Japan’s economic rise in the American imperium (Ikenberry and Inoguchi 2003, 2007). To be sure, with the passing of time Asia has become more important as war and occupation receded and as Japan’s reconstruction and economic clout made it Asia’s preeminent economic power. But it was Asia viewed from Tokyo through an American looking-glass. There was more than a whiff of the historical role that Japan sought after the Meiji restoration—casting itself in the role of interlocutor between Asia and the West.

Since 1945 Japan has experienced a phenomenal rise. Its economic fortunes were helped greatly by serving as the Asian armory in America’s global struggle against Communism, first in Korea in the 1950s and subsequently in Vietnam and Southeast Asia in the 1960s. The collapse of the Bretton Woods system and the two oil shocks of the 1970s set the stage for the economic rise of Japan in financial markets. The 1980s were the decade of Japan’s global ascendance as an economic superpower, ending in a speculative bubble that collapsed into economic torpor lasting more than a decade. In manufacturing Japan’s technological prowess is no longer unchallenged in defining East Asia’s economic frontiers. Japan has a mature economy that is trying to cope with an aging and thrifty population and with being one of the two main sources of credit for the United States. This completed the transformation of Japan’s strategic relationship with the United States from client to supporter state.

Japan has been important in supporting, both directly and indirectly, U.S. policies in a variety of ways (Krauss and Pempel 2004; McCormack 2007; Pyle 2007; Hughes and Krauss 2007). It helped refurbish the institutional infrastructure of international financial institutions following the Asian financial crisis of 1997, became for a while the world’s largest aid donor, and played a central role, especially in the mid-1980s, of intervening in financial markets to realign the values of the world’s major currencies. Since the 1980s Japan has accommodated the United States on issues central to the functioning of the international economy, with evident reluctance in opening Japanese markets for goods, services and capital and with an air of resignation in amassing close to a trillion dollars in reserves, substantial portions of which have helped to finance perennial U.S. budget and trade deficits.

Japanese aid allocations 2005-06

Japanese aid allocations 2005-06

With governments deeply involved in shaping their nations’ economic trajectories Japan expected to lead Asia both directly through aid, trade and advice and indirectly by providing an attractive economic model. Japan could not develop and grow unless Asia also developed and grew. By focusing on the politics of productivity, Japan hoped to sidestep political quarrels and dispel historical animosities. It thus sought to create the political conditions where its highly competitive industries could prosper through energetic export drives and smart foreign investments. Regional development and Japanese ascendance would thus be indelibly linked in a win-win situation which cloaked in liberal garments asymmetries in economic position and political power.

This strategy proved politically unworkable. In the 1960s different Japanese proposals for more formal regional integration schemes foundered on the deep suspicions that other Asian states, many of them former colonies or the targets of Japanese invasion, harbored against Japan. Having been rebuffed, the Japanese government settled after the early 1970s on more informal and market-based approaches to Asian integration. After the dramatic appreciation of the Yen in 1985 Japanese firms were quick to develop far-flung networks of subcontractors and affiliated firms. Foreign supplier chains of Japanese firms provided a new regional infrastructure for industries such as textiles, automobiles, and electronics. Thus Japanese investment had a deep impact on specific economic sectors, whole countries, and the entire Asia-Pacific region. And the regionalization of Japan’s economic power had the political benefit of diffusing much of the political conflict with the United States over bilateral trade imbalances. For Japanese enmeshment has helped create a more integrated regional economy in East Asia that is now fueled also by Korean, Taiwanese, Southeast Asian, and Chinese firms. The structural preconditions for this process of regionalization was the insatiable appetite of American consumers for inexpensive Asian products and the openness of American markets to imports from Asia. This outcome was fully compatible with the grand strategy of the United States which in the early 1970s normalized its relations with China to balance the Soviet Union during the Cold War, and which has consistently favored a far-reaching liberalization of markets. There would have been fewer and smaller Asian miracles and less Asian regionalism without the parking lots of American shopping malls filled in America’s irresistible emporium of consumption (DeGrazia 2005). And while it is premature to reach an informed assessment of the political consequence of the financial crisis that spread from Wall Street to Europe and throughout the global financial system, it seems reasonable to expect economic retrenchment on Main Street to affect the business prospects of Asian exporters who will look, as they have in recent decades, for growth in Asian markets while American consumers are squeezed and interests rise in the United States.

The role of supporter state was also evident in Japan’s national security policies. Although it was constrained for decades by a pacifist public culture and, somewhat less, by Article 9 of its Peace Constitution, the Japanese government has consistently adhered to policies that supported the United States, especially in the 1980s and with increased intensity since 9/11. To be sure there have been moments—such as in the mid-1970s and the mid-1990s—when the American staying power in Asia appeared sufficiently uncertain so as to suggest the need for possibly far-reaching changes in Japan’s security strategy. But these moments of uncertainty passed quickly, and Japan remained a close ally of the United States—then and now.

The reasons for Japan’s steadfast support have varied. The military, economic and political advantages of the American security umbrella were at the heart of the Yoshida doctrine and widely recognized in all political quarters. Expending less than 1 percent of Japan’s GDP for national defense was feasible because American taxpayers spent a lot more. And as Japan’s standing in the Asia-Pacific increased so did the pressure of the U.S. government to have the Japanese government play a more expansive, and expensive, role in regional security affairs—as a reliable junior partner of the United States. Some of Japan’s critics, both at home and abroad, detected in the 1980s a new tone of assertiveness and a new nationalism in Prime Minister Nakasone’s Japan. Two decades later, under Prime Ministers Koizumi and Abe the increase in an assertive Japanese nationalism was more prominently there for everybody to see. This was the political context in which the Japanese government, in February 2005, decided to raise its profile on one of the region’s most vexing problems, by issuing a joint security declaration with the United States that identified the peaceful resolution of the Taiwan issue as a shared strategic objective.

Prime Minister Koizumi’s strategy was to attach Japan even more closely to the United States than in the past (Samuels 2007: 86–108; Hughes and Krauss 2007: 160–63), while toying with the idea of bringing about an opening toward North Korea. After the 9/11 attacks the Diet passed in record time legislation permitting the dispatch of the Japanese navy to the Indian Ocean to provide logistical support for the U.S.-led coalition forces in Afghanistan. After the U.S. invasion of Iraq the Diet enacted legislation permitting the deployment of the Japanese army to Iraq to aid in reconstruction and the stationing of the Japanese navy and air force in the Persian Gulf to provide logistical support of the American war. In 2003 the Japanese government agreed to acquire a ballistic missile defense system which should be fully operational by 2011. And legislation introduced in 2005 gives the Prime Minister and military commanders the power to mobilize military force in response to missile attacks, without Cabinet deliberation in the course of analyzing particular empirical contexts or Parliamentary oversight. Since Japan is buying the main components of both weapons systems, the Patriot Advance Capability (PAC)-3 and the Aegis destroyers, from the United States, missile defense will further consolidate the U.S.–Japan alliance and tighten technological cooperation between the two militaries. In 2006 the U.S. and Japan completed a Defense Policy Review Initiative which strengthened the bilateral alliance to meet regional and global security threats. Toward that end and overriding significant local objections, Prime Minister Koizumi agreed to a substantial and costly realignment of U.S. bases in Japan. The practical implication of this agreement was to make Japan a frontline command post in the projection of U.S. military power, not only in East Asia but extending as far as to the Middle East. Like previous ones (Katzenstein 1996: 131–52) this was a further reinterpretation of the geographical scope of the U.S.–Japan security treaty and the mission of U.S. bases that went well beyond protecting the Japanese homeland and securing regional stability in East Asia. In fact, the Japanese and U.S. governments issued a joint statement stressing their shared global objectives of the eradication of terrorism and the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction. These important changes in the U.S.–Japan alliance are clearly linked to changes in the character of Japan and the East Asian context. Yet it is easy to overlook the fact that, with the disintegration of the Japanese Left, strong opposition to Japan’s playing a larger military role has changed as it has moved to other political parties; that opposition has not disappeared.

After 9/11 under Koizumi’s leadership Japan embraced what looked like a grand strategy of unquestioned security alignment with the United States. Japan appeared to be deeply invested in enhancing its special relationship with the United States, imitating that other island nation, Great Britain. But under Abe and Fukuda, leaders of astonishingly little staying power in office, within the context of the US-Japan security alliance, policy vacillated again between nationalism and Asianism. It remains to be seen how Japan’s strategy will fare under Prime Minister Aso as the United States moves beyond the Presidency of George W. Bush (C. Hughes 2007).

JAPAN AND CHINA: TWO TIGERS ON ONE MOUNTAIN?

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, China’s entrance into global markets and its gradual socialization into the role of a responsible regional power has been the single most important development affecting Japan and East Asia. This is not to argue that China has already replaced Japan as the preeminent economic power in Asia. Far from it. In 2002 Japan accounted for 13.5 percent of global GDP almost four times China’s figure. In terms of market exchanges, a better measure of regional and global power dynamics than purchasing power parity measures of GDP, Japan was leading China by a ratio of 4:1 and about 40:1 on a per capita basis. [2] After a decade of economic stagnation Japan’s share of the combined regional GDP of Northeast and Southeast Asia had slipped from 72 to 65 percent. And during the same period of explosive economic growth, China’s GDP as a proportion of Japan’s had increased from 13 to 23 percent (Katzenstein 2006: 2). [3] And even though the situation is changing from year to year, it is good to remember that until 2005 China was still lagging behind Germany as the world’s leading exporter. Current Chinese plans call for increasing the country’s GDP to $4.4 trillion by 2020, quadrupling the figure for the year 2000. If successful, China is likely to top Japan by that time in terms of market size measured at current exchange rates. Although these facts deflate a bit the breathless adulation with which some journalists and politicians are greeting the Chinese juggernaut, just as they greeted Japan’s in the 1980s, it is beyond doubt that very significant changes in China are having a profound effect on Asian and Japanese security.

China’s Rise

The political rise of China as a responsible regional power is an important political development (Kang 2007; Johnston 2004; Economy and Oksenberg 1999; Johnston and Ross 1999; Selden 1997). In the 1970s and 1980s China exchanged the role of a revolutionary for that of a realist power. China’s raison d’etat had a hard-edge of realpolitik that reminded some observers of Imperial Germany in the decades leading up to World War I. After more than a century of humiliation and isolation, was not China finally entitled to its rightful place under the sun? The international politics of sports, energy, xenophobic nationalism, economic mercantilism all seemed to point in that direction. Indeed, some realist theorists who had been baffled by the end of the Cold War and the disintegration of the Soviet Union in Europe, saw in Asia a region “ripe for rivalry” (Friedberg 1993/94).

China’s diplomacy, however, is not only hard-core realist. On many issues China has adopted a multilateral and accommodating stance. It has recognized the long-term advantages that accrue from its growing economic power and that dictate a diplomatic strategy supporting what has come to be known as China’s “peaceful rise.” This change is visible in comparison to both the United States and Japan. A shift in its national security doctrine in September 2002 established the United States as a revisionist power in the Middle East, in contrast to China playing the role of a status quo power in the international system. In its war against terror the U.S. government sought far-reaching changes. Most importantly it has claimed the right to preemptive attack, even under circumstances when there would be time and opportunity to seek approval from the United Nations. In sharp contrast China joined many other states in insisting on the importance of the legitimacy that international approval confers, as the U.S. had in the era of multilateralism that it had ushered in at the end of World War II. Anti-hegemonism became once again the watchword in Beijing as it balanced carefully a strong interest in China’s territorial sovereignty with growing demands of multilateral diplomacy, including on hot-button issues such as North Korea’s nuclear weapons program. In East Asia, in particular, instead of running the risks of Euro-centric balance-of-power politics China is seeking to return to a Sino-centric band-wagoning politics, thus creating political space for the cautious hedging strategies of a number of East Asian states. And Chinese diplomacy has shifted to include multilateral regional arrangements as an explicit tool to supplement its bilateral approach to regional and global issues.

In contrast to Japan with its more inward economic orientation, the distinctiveness of China’s ascendance lies in an economic might and political clout that is structurally predisposed to reinforce rather than challenge East Asia’s openness in a world of regions. Central to that structural predisposition is the realignment, rather than (re)unification, of a vibrant Chinese diaspora in Taiwan and Southeast Asia, with the Chinese state (Gomez and Hsiao 2004, 2001; Callahan 2003; Naughton 1997; Weidenbaum and Hughes 1996; Dædalus 1991). [4] Millions of overseas Chinese had left the Southern coast of China in the 19th century for destinations throughout Southeast Asia. Over time they became the economic elites in various countries. As successive waves of Asian states experienced their economic miracles, often with the help of developmental states, throughout East Asia networks of overseas Chinese were ready as important intermediaries connecting national political elites with foreign firms. While the core of Chinese business has remained family-controlled, surrounding layers of equity-holding and political control were gradually taken over by members of the indigenous political elites. In the 1990s, in terms of its sheer economic size the overseas Chinese economy in Southeast Asia reportedly ranked fourth in the world.

The category of “overseas Chinese” is ambiguous. In the 19th century the Chinese diaspora lacked a homogenous identity as it was divided, among others, by dialect, hometown, blood relationships and guild associations. As mainland China was engulfed in civil war, revolutionary upheaval and Maoist rule, a thin veneer of common expatriate experience grew, but not enough to conceal the enormous variability in the political experience and standing of the overseas Chinese in different parts of Southeast Asia. The cultural trait that helps define the overseas Chinese thus is an almost infinite flexibility in their approach to business.

The overseas Chinese presented the Chinese state with a formidable problem after the Communist Party seized power in 1949. The 1953 census listed the overseas Chinese as part of China’s population. And the 1954 Constitution of the Peoples Republic of China provided for representation of all overseas Chinese in the National People’s Congress (Suryadinata 1978: 9–10, 26, 29). However, conflict with Indonesia and other Southeast Asian states forced a change in policy. All of these states were wary of the political allegiance of their ethnic Chinese populations. After 1957 Chinese foreign policy encouraged the overseas Chinese to seek local citizenship and local education. And since 1975 China’s constitutions have stripped overseas Chinese of membership in the National People’s Congress. During the last generation an overwhelming number of overseas Chinese have accepted citizenship in their new homelands. The term overseas Chinese now denotes ethnic Chinese of Southeast Asian birth and nationality.

In China both provincial and central governments have sought to strengthen the relationship between China’s surging economy and the overseas Chinese, and especially Taiwan, through an active encouragement of foreign investment, remittances and tourism. What Barry Naughton (1997) calls the “China Circle” connects Hong Kong, Taiwan, and the overseas Chinese throughout Southeast Asia. Upward of one million Taiwanese businessmen now live in China, undercutting ineffective attempts of the Taiwanese government to resist the strong pull of China’s surging economy. And it is easy to forget that outside of this China circle the overseas Chinese constitute also a North American and indeed a global diaspora.

Since the late 1970s China has attracted half a trillion dollars in foreign investment, about ten times the total foreign investment that has flown into Japan since 1945. Between 1985 and 1995 about two-thirds of realized foreign investment in China is estimated to have come from domestic Chinese sources which used Hong Kong to circumvent domestic taxes, one-third from foreign investors. Since 1995 this proportion is widely believed to have reversed itself. Of the 250 billion dollars of total foreign investments, perhaps as much as half has come from Taiwan, and additional undetected funds have flown in from Southeast Asia. [5] Whatever the precise figures, in the coming years even closer tie-ups between overseas and mainland Chinese business are the next phase in the global spread of Asian business networks. It is these market- and state-driven tie-ups, not formal political institutions, which are the defining characteristic of the rise of China and the role of Asia in world politics. The evolution of Chinese capitalism thus is not only a domestic but also a regional and global phenomenon. Across a broad range of issues, uniquely in Asia, China is linked inextricably to the Asia-Pacific. And as a rapidly emerging creditor of the United States and a looming military rival at least in the eyes of important segments of the American defense establishment, China is also linked intimately to the American imperium.

Japan and China

Japan must come to terms with a China that is both a vital economic partner and also a political rival in East Asia (Lam 2006; Dreyer 2006; Cohen, 2005; Abramowitz, Funabashi and Wang 2002; Friedman 2000; Wang 2000; Zhao 1997; Taylor 1996; Iriye 1992). Japan adheres to an increasingly international economic and a fully internationalized security strategy. In sharp contrast, China follows a fully international economic and a more conventional national security strategy. Both reinforce the porosity of East Asia. In the latter stages of the Koizumi administration the deterioration in Sino-Japanese relations was striking. Between May 2004 and October 2005, for example, the relations between these two regional powers were affected negatively by a series of high-profile political events, on average once a month (Pei and Swaine 2005: 5). By the end of Koizumi’s Prime Ministership, Japan’s relations with China had reached rock-bottom. In 2005 just under 10 percent of the Japanese and Chinese public held favorable views of the other country (Sato 2007: 3; Tanaka 2007). Perceptions of imagined slights and hurt pride have played out on both sides against very different interpretations of the past. They are illustrated by the strong opposition of the Chinese public to any historical revision in the interpretation of Japan’s role as the aggressor in the East Asian war in Japanese textbooks. Japanese fear and envy feed anti-Chinese sentiments as Chinese rates of growth since the early 1990s have outstripped Japanese rates by margins of 13:1 in per capita gross domestic product and ownership of personal computers, 12:1 in patent applications, 11:1 in total trade, and 9:1 in research and development expenditures (Pei and Swaine 2005: 6). Domestic politics create political incentives in both countries to magnify and exploit popular sentiments, driven by factional infighting in China and electoral strategizing in Japan. China and Japan thus risk being trapped in a political relationship of deepening suspicion and enmity that runs counter to their growing economic interdependence and the prospect of joint gains.

Prime Minister Abe’s visit to Beijing in October 2006, right after he took over from Koizumi, and the return visit of Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao in April 2007 have helped improve the political climate between the two countries. Both governments saw the change in Japanese leadership as a chance for bringing about an improvement in bilateral relations. Furthermore, there exist concrete plans for resumption of more frequent meetings between the political leadership of the two countries (Pilling 2006; Dickie and Pilling 2007). But many contentious issues persist under the surface. Most importantly, Prime Minister Abe remained deliberately ambiguous in his talks with the Chinese government and Japanese journalists about a possible visit of the Yakusuni shrine, avoiding the need to tell the Chinese that he would not and domestic supporters that he might be making such a visit. His resignation made the issue mute as his successor, Prime Minister Fukuda, was committed to better relations with Japan’s East Asian neighbors, illustrated by the agreement with China over the Diaoyutai/Senkaku islands in June 2008. It remains to be seen how Prime Minister Aso will handle this issue. Domestic political weakness may force him to abandon a diplomatically sensible ambiguity on Yasukuni Shrine in favor of shoring up his nationalist base in Japan with a gesture that the Chinese leadership may be unable or unwilling to ignore. Such a political move would not come as a total surprise. As Foreign Minister Aso, more than Prime Minister Abe, favored a “value-based” foreign policy that creates an “arc of freedom and prosperity across the democracies in Pacific Asia” designed to exclude China. For its part China remains very suspicious of Japan’s reinvigorated security alliance with the United States, the refashioning of Japan’s national security apparatus, and plans to revise the constitution (Pei 2007). Chinese exploitation of natural gas reserves in the middle of disputed waters in the East China Sea, and Japan’s hope for Chinese backing for its permanent seat on the UN Security Council provide additional roadblocks for improvement in political relations between two governments.

The domestic, regional and global contours of politics suggest that the evolution of Sino-Japanese relations will be shaped by a mixture of engagement and deterrence in their bilateral relations, by their competitive and complementary region-building practices in an East Asia that will resist domination by either country (Katzenstein 2006), and by the cultivation of their different strategic and economic links to the American imperium. Japan has had a deep strategic partnership with the United States for more than half a century. For China, those links are rooted in a developmental trajectory that prizes economic openness and that increasingly seeks global engagement on all fronts. Through Japan and China a porous Asia is tethered in both its security and economic relations to the American imperium. The U.S. presence in East Asia can help stabilize Sino-Japanese relations at least in the near- and medium-term while political efforts at East Asian region-building proceed. Despite the political turbulence and rapid changes in Sino-Japanese relations, for some years to come the American imperium and East Asia may remain politically compatible. And because their political strategies are so different, the two tigers may learn how to live on the same mountain.

Peter J. Katzenstein is the Walter S. Carpenter, Jr. Professor of International Studies at Cornell University and the President of the American Political Science Association. His research and teaching lie at the intersection of the fields of international relations and comparative politics.

This is a revised and updated excerpt from chapter 1 of Peter J. Katzenstein, Rethinking Japanese Security: Internal and External Dimensions (New York: Routledge, 2008), with permission of the publisher. Posted at Japan Focus on October 14, 2008.

Notes

[*]I would like to thank Mark Selden for much more than his careful editing of the manuscript and his superb critical comments and suggestions. The errors of omission and commission that remain are simply the result of my inability or unwillingness to follow his good advice.

[1] This section summarizes some of the major arguments in Katzenstein 2005.

[2] In terms of purchasing power parity, according to some estimates China’s economy surpassed Japan’s as early as 1994 (Shiraishi 2006: 10).

[3] According to the IMF, by 2006 Japan’s GDP was $4.367 trillion compared to China’s figure of $2.630 trillion, a ratio of 1.66:1. (accessed 4 August 2007)

[4] The material in the next four paragraphs draws on Katzenstein 2005, 63–67.

[5] Interviews, Tianjin and Beijing, March–April 2006.

References

Abramowitz, Morton I., Funabashi Yoichi, and Wang Jisi (2002) China-Japan-U.S. Relations: Meeting New Challenges, Tokyo and New York: Japan Center for International Exchange.

Buruma, Ian (1994) The Wages of Guilt: Memories of War in Germany and Japan, New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux.

Callahan, William (2003) “Beyond Cosmopolitanism and Nationalism: Diasporic Chinese and Neo-Nationalism in China and Thailand,” International Organization, 57 (Summer): 481–517.

Chase, Robert; Hill, Emily and Kennedy, Paul (eds) (1999) The Pivotal States: A New Framework for U.S. Policy in the Developing World, New York: Norton.

Chow, Jonathan T. (2005) “ASEAN Counterterrorism Cooperation since 9/11,” Asian Survey, 45, 2: 302–21.

Cohen, Danielle F.S. (2005) Retracing the Triangle: China’s Strategic Perceptions of Japan in the Post-Cold War Era, Maryland Series in Contemporary Asian Studies Number 2-2005 (181).

Dædalus (1991) The Living Tree: The Changing Meanings of Being Chinese Today, (Spring).

DeGrazia, Victoria (2005) Irresistible Empire: The American Conquest of Europe, Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Dickie, Mure and Pilling, David (2007) “Warm Words, Old Wounds: How China and Japan are Starting to March in Step,” Financial Times, April 9, p. 9.

Dreyer, June Teufel (2006) “Sino-Japanese Rivalry and Its Implications for Developing Nations,” Asian Survey, 46, 4 (July/August): 538–57.

Economy, Elizabeth and Oksenberg, Michael (eds) (1999) China Joins the World: Progress and Prospects, New York: Council on Foreign Relations Press.

Friedberg, Aaron (1993/94) “Ripe for Rivalry: Prospects for Peace in a Multipolar Asia,” International Security, 18, 3 (Winter): 5–33.

Friedman, Edward (2000) “Preventing War between China and Japan,” pp. 99–128 in Edward Friedman and Barrett L. McCormick (eds) What If China Doesn’t Democratize: Implications for War and Peace, Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe.

Gomez, Edmund Terence and Hsiao, Hsin-Huang Michael (eds) (2001) Chinese Business in Southeast Asia: Contesting Cultural Explanations, Researching Entrepreneurship, Richmond, Surrey: Curzon.

—— (2004) Chinese Enterprise, Transnationalism, and Identity, London: RoutledgeCurzon.

Green, Michael J. (2007) “Japan is Back: Why Tokyo’s New Assertiveness is Good for Washington,” Foreign Affairs, 86, 2 (March/April): 142–7.

Hughes, Christopher W. (2007) “Not Quite the ‘Great Britain of the Far East’: Japan’s Security, the US-Japan Alliance and the ‘War on Terror’ in East Asia,” Cambridge Review of International Affairs 20, 2 (June): 325–38.

—— and Krauss, Ellis S. (2007) “Japan’s New Security Agenda,” Survival, 49, 2 (Summer): 157–76.

Ikenberry, G. John, and Takashi Inoguchi (eds) (2003) Reinventing the Alliance: U.S.-Japan Security Partnership in an Era of Change, New York: Palgrave.

—— (2007) The Uses of Institutions: The U.S., Japan and Governance in East Asia, New York: Palgrave.

Iriye, Akira (1992) China and Japan in the Global Setting, Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Johnston, Alastair Iain (2004) “Beijing’s Security Behavior in the Asia-Pacific: Is China a Dissatisfied Power?” pp. 34–96 in J.J. Suh, Peter J. Katzenstein and Allen Carlson (eds) Rethinking Security in East Asia: Identity, Power, and Efficiency, Stanford: Stanford University Press.

—— and Ross, Robert S. (eds) (1999) Engaging China : The Management of an Emerging Power, London: Routledge.

—— and Stockmann, Danie (2007) “Chinese Attitudes toward the United States and Americans,” pp. 157–95 in Peter J. Katzenstein and Robert O. Keohane (eds) Anti-Americanisms in World Politics, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Kang, David C. (2007) China Rising: Peace, Power, and Order in East Asia, New York: Columbia University Press.

Katzenstein, Peter J. (1985) Small States in World Markets: Industrial Policy in Europe, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

—— (1996) Cultural Norms and National Security: Police and Military in Postwar Japan, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

—— (ed.) (1997) Tamed Power: Germany in Europe, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

—— (2005) A World of Regions: Asia and Europe in the American Imperium, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

—— (2006) “East Asia—Beyond Japan,” pp. 1–33 in Peter J. Katzenstein and Takashi Shiraishi (eds) Beyond Japan: The Dynamics of East Asian Regionalism, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

—— and Robert O. Keohane (eds) (2007) Anti-Americanisms in World Politics, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

—— and Takashi Shiraishi (eds) (1997) Network Power: Japan and Asia, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

—— and —— (eds) (2006) Beyond Japan: The Dynamics of East Asian Regionalism, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Krauss, Ellis S. and Pempel, T.J. (eds) (2004) Beyond Bilateralism: U.S.-Japan Relations in the New Asia-Pacific, Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Lake, David (1988) Power, Protection, and Free Trade: International Sources of U.S. Commercial Strategy, 1987–1939, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Lam, Peng Er (ed.) (2006) Japan’s Relations with China—Facing a Rising Power, London: Routledge.

Larsson, Tomas Henrik (2007) “Capitalizing Thailand: Colonialism, Communism, and the Political Economy of Rural Rights,” Ph.D. dissertation, Government Department, Cornell University.

Leheny, David (2005) “Terrorism, Social Movements, and International Security: How Al Qaeda Affects Southeast Asia,” Japanese Journal of Political Science, 6, 1: 87–109.

McCormack, Gavan (2007) Client State: Japan in the American Embrace, London: Verso.

Midford, Paul (2006) Japanese Public Opinion and the War on Terrorism: Implications for Japan’s Security Strategy, Washington DC: East-West Center.

Mochizuki, Mike M. (2004) “Japan: Between Alliance and Autonomy,” pp. 103–38 in Ashley J. Tellis and Michael Willis (eds) Confronting Terrorism in the Pursuit of Power: Strategic Asia, 2004–2005, Seattle: National Bureau of Asian Research.

Nabers, Dirk (2006) “Culture and Collective Action: Japan, Germany and the United States after September 11, 2001,” Cooperation and Conflictn 41, 3 (September): 305–26.

Naughton, Barry (ed.) (1997) The China Circle: Economics and Technology in the PRC, Taiwan, and Hong Kong, Policy Studies 27, Washington DC: Brookings Institution.

Pei, Mixin (2007) “Ways to End the Sino-Japanese Chill,” Financial Times, April 10, p. 13.

—— and Swaine, Michael (2005) “Simmering Fire in Asia: Averting Sino-Japanese Strategic Conflict,” Policy Brief 44 (November), Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Pew Global Attitudes Project (2007) “Global Unease with Major World Powers: Rising Environmental Concern in 47-Nation Survey” (June 27). (accessed 13 July 2007).

Pilling, David (2006) “‘To Befit the Reality’: How Abe Aims to Secure Japan Its Desired World Status,” Financial Times, November 1, p. 11.

Pyle, Kenneth B. (2007) Japan Rising: The Resurgence of Japanese Power and Purpose, New York: Public Affairs.

—— (2007) Securing Japan: Tokyo’s Grand Strategy and the Future of East Asia, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Sato, Peter (2007) “The View from Tokyo: Melting Ice and Building Bridges,” China Brief, 7, 9 (May 2): 2–4.

Selden, Mark (1997) “China, Japan and the Regional Political Economy of East Asia, 1945–1995,” pp. 306–40 in Peter J. Katzenstein and Takashi Shiraishi (eds) Beyond Japan: The Dynamics of East Asian Regionalism, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Steinberg, David I. (ed.) (2005) Korean Attitudes toward the United States: Changing Dynamics, Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe.

Stubbs, Richard (1999) “War and Economic Development: Export-Oriented Industrialization in East and Southeast Asia,” Comparative Politics, 31, 3: 337–55.

—— (2005) Rethinking Asia’s Economic Miracle, Baskingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Suryadinata, Leo (1978) “Overseas Chinese” in Southeast Asia and China’s Foreign Policy: An Interpretive Essay, Singapore, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Research Notes and Discussion Papers No.11.

Tanaka, Akihiko (2007) “Asian Opinions: A Mixed Bag for Japan,” Japan Echo (June): 31–4.

Taylor, Robert (1996) Greater China and Japan: Prospects for an Economic Partnership in East Asia, London: Routledge.

Wang, Qingxin Ken (2000) Hegemonic Cooperation and Conflict: Postwar Japan’s China Policy and the United States, Westport: Praeger.

Weidenbaum, Murray and Hughes, Samuel (1996) The Bamboo Network: How Expatriate Chinese Entrepreneurs Are Creating a New Economic Superpower in Asia, New York: Free Press.

Zhao, Suisheng (1997) Power Competition in East Asia, New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Zhu Tianbiao (2000) “Consistent Threat, Political-Economic Institutions, and Northeast Asian Developmentalism,” Ph.D. dissertation, Government Department, Cornell University.

—— 2002. “Developmental States and Threat Perceptions in Northeast Asia,” Journal of Conflict, Security and Development, 2, 1: 6–29.