Lawsuit Seeks Japanese Government Compensation for Siberian Detention: Who was Responsible for Abandoning Japanese Soldiers and Settlers in Mainland Asia After World War II?

Murai Toyoaki

Nobuko ADACHI translator

Why Compensation?

We submitted a “Request for Compensation for Siberian Detention” to the Kyoto Local Court on December 26, 2007, seeking redress from the Japanese government. We are asking for ¥30,000,0001 for each plaintiff as compensation (and accepting ¥10,000,0002 compensation as partial settlement). At the beginning of the suit the number of plaintiffs was thirty. However that number has increased to forty-one today. Testimony from each plaintiff will be heard beginning on December 15, 2009.

The lawsuit requesting compensation from the Japanese government for Siberian detention questions the legality and responsibility of the Japanese government for abandoning many soldiers and civilians in Asia at the end of World War II. Before World War II ended in Asia on the day Japan accepted the Potsdam Declaration—August 15, 19453—the Soviet Union declared war against Japan on August 8, 1945, renouncing the Japan-Soviet Neutrality Treaty of 1941. The USSR immediately crossed the borders of northeast China (Manchuria), northern Korea, and southern Sakhalin (which were all Japanese colonies), and the Kuril Islands. They engaged in combat with the Japanese army in these areas. Even after the Potsdam Declaration’s de facto ending of World War II, fighting between Japan and the Soviet Union continued through early September until a cease fire was declared.

Joseph Stalin,4 the leader of the Soviet Union and the Head of the National Defense Committee of the USSR, on August 23, 1945 issued the top secret order “Regarding the Arrest of Half a Million Japanese Soldiers: How and Where to Detain Them, and How to Utilize Their Labor”. As a result, after hostilities ended, the Japanese soldiers who had been disarmed and gathered in mustering-out areas in Manchuria, North Korea, South Sakhalin, and the Kuril Islands were instead taken swiftly to the Soviet Union as POWs. These POWs were detained for long periods of time after the war, some up to five years. It is said that the number of detainees was well over 600,000 and that there were some 2000 detention camps scattered throughout the Soviet Union, most in Siberia. Probably at least 60,000 detainees died miserably in custody due to the severe cold weather, starvation, or heavy forced labor. Those who returned to Japan later suffered from many secondary physical and psychological after-effects.

It is true that this Siberian detention was technically “Stalin’s crime.” It was he who bears the primary legal responsibility, as it was Stalin who completely ignored international law and kept these POWs illegally for such a long period. However, the Japanese government also bears some responsibility for its policy of abandoning its soldiers and civilians left behind in mainland Asia.5 These abandoned people, who then became Soviet forced-labor prisoners, were offered as sacrificial lambs to the Soviets as compensation for Japan’s invasion of Asia, and to appease the Soviets to allow Japan to remain unoccupied after the war, and to remain an independent nation in the long term.

Even before the Potsdam Declaration, the Japanese government had informed the Soviets that they would offer their soldiers and civilians left behind to do heavy labor in the USSR if the Soviets promised that Japan would remain a sovereign nation and retain its government. This was again proposed to the Soviet Union after the Japanese government accepted the Potsdam Declaration. Because of the Japanese government complicity, the Soviets could transport over 600,000 Japanese citizens to 2,000 prison camps located all over the Soviet Union (including Siberia) so swiftly. Furthermore, the Japanese government ignored the plight of its people, allowing them to suffer from the elements, poor nutrition, and heavy forced labor for such a long period.

Today the average age of the plaintiffs—former soldiers who had been detained in Siberia and other places—is eighty-three. They have stood up and demanded compensation from the Japanese government for their Siberian detention, and because they were abandoned, have a strong desire to obtain redress from the government before they pass away.

The Original Issues Involved in the Siberian Detention

After the Meiji Government (1868-1912) was established, the new government confronted strong Western-military threats. Thus, their most important immediate aim was to establish a strong military. In 1895 Japan defeated the Chinese in the Sino-Japanese war. However, this victory created military tensions with Russia over the Korean Peninsula. In 1898, Russia obtained from China the rights to construct the East China Railway and to use Port Arthur and Dalian as naval stations. In 1900, the Russian military moved into Manchuria when the Boxer Rebellion occurred. Later, the presence of the Russian army near the Korean peninsula compelled the Korean government to sign a treaty with Russia. The Japanese government saw these Russian military movements as a threat to Japan. As a consequence, the Japanese government formed the Anglo-Japanese Alliance and prepared to repel a possible Russian southern invasion.6 In 1904, when Russia rejected Japan’s demand to withdraw Russian troops from Manchuria, the Russo-Japan war began.

Japanese woodblock image of Russo-Japanese War

The war went in favor of Japan, and with the United States as an intermediary, ended in 1905.7 Russia agreed that the southern half of Sakhalin Island would become a part of Japan, and that Japan would get rights and interests in Manchuria. Japan would also take control of the Liaodong peninsula and the Korean peninsula from Russia. Japanese troops were stationed along the Southern Manchurian Railway.

In 1910, Japan made the Korean peninsula a colony and prepared military bases for an advance into the Chinese mainland. After the Russian Revolution in 1917, Japan’s Kwantung Army8 invaded Siberia along with Western troops, and temporarily occupied it. Later, Japan instigated the Mukden Incident of 19319 as an excuse to invade and occupy Manchuria [creating the puppet-state of Manchukuo in 1932]. After this, tensions between Japan and Russia along the Manchurian border remained high. In 1939, the Nomonhan Incident occurred.10 The Russian and Japanese militaries clashed on the Soviet/Mongolian border. The result was Japan’s total defeat. After that, Japan’s strategic policy changed to “Protect the North and Invade the South.”

Japanese painting of Nomonhan battle

After suffering worldwide condemnation due to the Mukden Incident, Japan decided to leave the League of Nations in 1933, thus isolating itself internationally. Japan formed the Tripartite Pact of 1940 with two other nations that had also left the League: Nazi Germany and Mussolini’s fascist Italy. These three dictatorships confronted the rest of the world. Although Germany had signed a nonaggression treaty with the Soviet Union in 1939, Germany renounced it and invaded the Soviet Union in June of 1941. In order to avoid having a two-front war in Europe and the Far East, the Soviets signed the Soviet-Japanese Neutrality Pact11 in April 1941, allowing the Soviets to concentrate on its war with Germany.

It is obvious that the political relationship between Japan and Russia during the pre-World War II period was a series of wars and truces. These were all caused by competition for colonies and racial and ethnic animosities.

However, well into the Pacific War (which started in December, 1941) Japan realized that things were not going as well. Thus, the Japanese government began preparing for possible war with the Soviet Union. Yet, at the same time, Japan also clung to the hope that the Soviet-Japan Neutrality Pact—which actually remained in effect until April, 1946—would allow the USSR to act as an intermediary with the Allies and negotiate a peace. Nonetheless, Japan knew that when the Soviets’ war with Germany ended, and they were transferring troops to the Far Eastern Front, war between Japan and the USSR was possible. But if Soviet mediation with the Allies occurred, the Japanese government decided that on condition that Japan preserved its status as a sovereign nation, it would make many concessions. As a result, Japan would propose (as stated in “Outline of the Peacemaking Process”) that if Soviet intervention occurred before the war ended, “as reparation Japan would offer Japanese labor to the Soviet Union.” In a report submitted on August 29, 1945 to Soviet General Vasilevsky,12 the Imperial Army’s Kwantung headquarters stated: “Concerning Japanese soldiers, … some will stay on in Manchuria to join your [Soviet] troops and others will return to Japan. But even the soldiers who are to be discharged, until the time comes for them to return to Japan, they will help your army as much as possible.” In other words, this was the start of an official Japanese policy to abandon its soldiers.

As explained above, abandoning its soldiers and civilians became a Japanese government policy of attempting reconciliation with the Soviets after they entered the war. As a strategy of last resort, the Japanese government planned to exchange these people in return for its survival as a nation.

The Japanese Government’s Policy of Abandoning Its Soldiers and Civilians

In April 5, 1945, Vyacheslav Molotov,13 the foreign minister of the Soviet Union, informed Ambassador Satō Naotake14 that his government would not renew the Soviet-Japanese Neutrality Pact. The war situation was deteriorating for Japan (for example, the losses at the Battle of Iwo Jima and the Great Tokyo Air Raid of March 1945, and the American invasion of Okinawa in April, 1945). Japanese government officials met the following month, May, and finally discussed ways of possibly ending the war through negotiations via the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, rather than through the mad military policy of fighting to the last man, woman, and child. In order to make it easier for the Soviets to negotiate a relaxation of the Potsdam Declaration with the other Allied nations, Japan wanted to demonstrate that it was prepared for total acceptance of both the Potsdam ideals and the Soviet-Japanese Basic Convention of 192515 [as long as Japan could remain a sovereign political entity]. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs decided to propose to the Soviets the following concessions:

1) the return of southern Sakhalin island to the Soviet Union,

2) the dissolution of the Russian-Japanese Fisheries Conventions of 1907 and 192816,

3) the opening of the Tsugaru Straits of Japan to the Soviet Union,

4) the transfer of rights to the railways in northern Manchuria to the Soviet Union,

5) acceptance of Soviet expansion into the Inner Mongolian Autonomous Region, and

6) offering the northern part of the Kuril Islands to the Soviet Union if Japan decided it needed to lease the ports of Dalian or Port Arthur.

The Soviet Union, on the other hand, had a plan to invade Manchuria as early as 1943. We know this, as in October 1943, Stalin mentioned this plan at a meeting of the foreign ministers and secretaries of Great Britain, the Soviet Union, and the United States in Moscow. The following month, the Soviets also mentioned it at the Tehran Conference between the US, the UK and the USSR. And at Yalta in February 1945, “The Yalta Secret Agreement Regarding the Far East” was made allowing the Soviets to invade Manchuria. The agreement said the Soviet would enter the war [within 90 days after the defeat of Germany] and after the war the Allies promised, among other things, that “Japan will return South Sakhalin and other nearby islands to Russia,” and that “The Kuril Islands will become a part of Russia.” This compensation was quite excessive compared to what the Soviet Union contributed to the defeat of Japan, and these territorial issues are still important problems in the world today.

Churchill, Roosevelt and Stalin at Yalta

The Soviets had been preparing for participation in the war against Japan for quite some time, so there was actually no possibility of their entering into peace negotiations. In other words, in spite of what the Japanese government hoped, the Soviet Union had no plan to end the war with Japan, nor did it have any intention to propose peace negotiations between Japan and the Allies. The Japanese government knew the Soviets were transferring large numbers of personnel and equipment for war against Japan. Still, Japan pitifully negotiated with the Soviet Union to end World War II. Furthermore, the offers included almost all the Japanese colonies, as well as sizeable numbers of Japanese laborers. This latter offering meant abandoning many of its own soldiers and civilians to Soviet imprisonment.

As the Potsdam Conference17 approached, on July 12, 1945 the Japanese war council decided to send Konoe Fumimaro18 as a special envoy of the Emperor, to give a personal letter to the Soviets. The council thought that nothing would change by just sending a normal diplomat to negotiate. As soon as he received the telegram from Japan regarding this special envoy, Japan’s Ambassador Satō in Moscow asked to see Molotov. However, Molotov declined this request, saying he was too busy preparing for the Potsdam meeting. As for Japan, in its “A Request for Peace Negotiations”,which Konoe hoped to present to the Soviets, the government said

Considering the domestic and world situations, we do not ask for impossible things, only that we could continue on as a nation as a condition of our negotiations. As long as our nation can survive, we will be able to solve other things later.

As seen in this statement, it is clear that Japan’s aim was only its “continuation as a nation.” Furthermore, as a condition for negotiations, it used the most extreme language, saying things like “We make no demands other than to be allowed to continue as a nation” and “We will agree to anything as long as we can keep the Japanese mainland.” In the section on “Military and Naval Forces,” the government said “All soldiers will be brought back to Japan; however, if the Soviets need them, we agree to let the Soviets keep our soldiers for a while.” And they added language like “Young soldiers can be used for temporary labor.” Finally, the war council wrote in the “Compensation and Others Matters” section, “As one of our concessions, we agree to offer some laborers.” In other words, the Japanese government let its own soldiers be engaged in forced labor under orders of a foreign army.

The Soviets declared war on Japan on August 8, 1945; Japan accepted the Potsdam Declaration on August 15, 1945. However, battles between Soviet and Japanese forces continued even after Japan signed the Instrument of Surrender on September 2, 1945. Hostilities finally ceased on September 9, 1945. The Imperial Rescript of Surrender (Gyokuon-hōsō) was sent to each soldier in the battlefield on the afternoon of August 15th. However, some General Staff officers resisted the order to surrender. This delay benefited the Soviets. From the time they declared war on Japan until the fighting finally stopped, the Soviets occupied the former Manchuria, the former Kwantung Leased Territory, northern Korea, southern Sakhalin, and the Kuril Islands.

Stalin, Truman and Churchill at Potsdam

The first order from Stalin regarding the Siberian detentions was a top-secret telegram, “The Instruction for Transferring POWs,” sent on August 23rd. In this telegram Stalin told his commanders to select half a million Japanese POWs—who were physically fit enough for the far-north Siberian environment—for heavy labor. He also instructed them on how to transfer these POWs, gave instructions about their clothes and food, named the locations of prison camps, and told how many should go to each camp. In the end, the actual number of detainees was something more like 630,000, and they were moved to pre-designated detention centers, as ordered by Stalin: Magadan, Yakutsk, and Norilsk in the Far North region; the Ural region; and areas around Moscow, the Caucasus Mountains, Kyrgyz, and Mongolia.

It is easy to assume that the Soviets had prepared this project ahead of time because discussed in the telegram were reports about the demands for physical labor at each camp—even several months prior to the date of the telegram. Especially when we consider the transfer of such a large number of detainees, and the precise numbers to be sent to each camp, it is clear that pre-planning was required.

On August 26, 1945, Staff Officer Asaeda Shigeharu19 at Imperial Army headquarters, submitted to the Soviets a report on the state of the cease-fire of the Kwantung Army. It consisted of two parts. In the first part it reported the number of Japanese soldiers in each area, the number of wounded soldiers, the number of weapons and ammunition handed over, and the number (and addresses) of Japanese civilians in the former Japanese colonial areas. In the second part it reported on the decision of the Japanese government for “proceeding from this time forward.” That is, “We request that the Soviet Union take care of our soldiers and civilians who are disarmed on the continent and let them become settled.” Here, use of the term “settle” [dochaku seshimeru]—instead of asking the Soviets to “temporarily take care of them until they return to Japan”—tells us that the Japanese government was saying to the Soviets that, in essence, these people would be theirs, that they would not necessarily return to Japan. This policy had been decided upon on August 26th. We clearly see here Japan’s intent to abandon its soldiers and citizens.

We can see this policy also in the report submitted under the banner of the Kwantung Army headquarters to General Vasilevsky on August 29, 1945. After asking for treatment for wounded soldiers and care for the remaining Japanese civilian migrants, the headquarters wrote,

Next to consider is the treatment of soldiers. Of course you have your own plan for them, but we believe [it will be more productive for you] to use the Japanese immigrants who have established themselves (and made their families) in Manchuria to work for you—as well as any Japanese soldiers who wish to stay—and let the others gradually return home to mainland Japan. We hope that while they are waiting to return to Japan, you can use their labor to help your troops.

If the Soviets were to put these people back to work at their previous jobs

we assume that they would be of help to your troops in getting food, providing transportation, and running general industries. We would like to offer others to work in the coal mines (such as in Fushun City in Liaoning, China), or for the South Manchukuo Railways Co., Manchukuo Electric, and Manchukuo Steel. You would then be secure in getting coal for winter, which is the most difficult problem at that time.

As can be seen in the above statements, the Japanese government policy was to accept all requests made by the Soviets, from the early period of negotiations to the end of the war. Furthermore, both General Asaeda Shigeharu (Staff Officer of the Imperial Army headquarters) and Field Marshal Hata Shunroku20 (Commander of the Kwantung Army) implemented the policy of abandoning Japanese citizens immediately after surrender.

The Actual Conditions of Siberian Detention

According to Paragraph 9 of the Potsdam Declaration, which was issued immediately after the end World War II, Japanese soldiers would be returned to their homeland to live their lives in peace. However, some 630,000 Japanese were placed in Soviet custody under the command of the Soviet army. They were dispersed to about 2,000 detentions camps located in the extreme northern Arctic and Siberian areas, Central Asia and Mongolia, and European Russia. There the detainees were forced to engage in hard physical labor for many years by the Soviet army. They worked mainly in railway, canal and road construction, coal mining, and forestry. The Soviets assigned tough tasks, and when someone failed to fulfill an assignment, all the detainees got less food under the Soviet policy of collective responsibility. This was really severe punishment for the detainees, as even the normal amount of food they were given was not sufficient for the kind of work they were engaged in. Because of severe cold weather and poor health conditions in the camps, 68,000 former soldiers died and about 46,000 developed severe physical ailments, which lasted the rest of their lives. Furthermore, many detainees simply disappeared in the camps or en route from the POW camps to the labor camps.

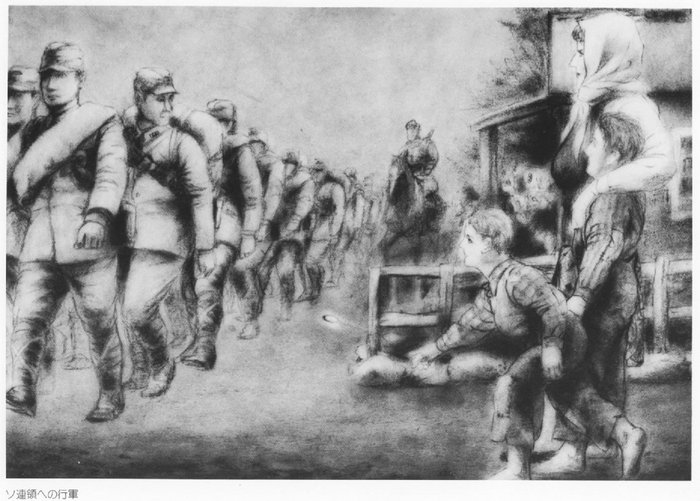

Yoshida Isamu’s drawing of Japanese troops entering Siberia

The Illegality of the Japanese Government’s National Policy of Abandoning its Soldiers

In the lawsuit demanding compensation, we make the following three claims:

(1) The Japanese Government Committed an Unlawful Act Under the Pre-war Constitution by Not Bringing Draftees Home After World War II Ended

These former Japanese soldiers—including our plaintiffs—were all serving overseas in the military by order of Japanese government when they were captured by the Soviets. It is clear that when a nation orders its people to engage in dangerous missions overseas, it has the obligation to see to it that they return as safely and swiftly as possible after their mission. In this case their mission clearly ended when the war ended. This obligation was no different even under the pre-war Imperial Japanese constitution. For example, both Article 19 (the Order for the Drafting of Citizens) and Article 30 (the Order for Mobilizing Citizens for War) of the former constitution allowed draftees to return home after their conscription period ended. It is clear that the government made these plaintiffs go to work for the Soviets after the war rather than allowing them to return home. This policy of abandoning citizens to the Soviets is clearly an illegal action. Since the government committed an unlawful act, it is obligated to compensate the plaintiffs for their losses.

(2) The Japanese Government Committed an Unlawful Act by Not Following the Law for Military Responsibility and Safety

Under current law it is required that soldiers and public service personnel fulfill their duties (beginning Section 1, Paragraph 101 of the National Public Service Law; and Section 1, Paragraph 60 of the Self-Defense Forces Law). Likewise, they must obey the law and orders from their superiors (Section 1, Paragraph 98 of the National Public Service Law; Article 56 and Article 57 of the Self-Defense Forces Law). In return, the country has an obligation to pay fair wages for this work (Paragraph 62 of the National Public Service Law; Article 4 of Staff Wages of the Defense Agency Law). At the same time, the government not only has the responsibility, but the requirement “to supervise the places, institutions, and equipment of public service personnel—as well as providing protection for them from life-threatening danger—when said personnel are pursuing their public service duties under orders from the government or their supervisors” (decision of the Supreme Court, February 25, 1975).

It is only fair to apply these understandings—about the government providing for the safety of Japanese soldiers—to the current case because the relationship between the government and its soldiers was even more comprehensive and unconditional under the former constitution than the current constitution. In other words, our plaintiffs pursued their duties faithfully in order to “benefit the nation” even though their lives were in danger. They followed the orders of their superiors, obeying them absolutely following strict military discipline (as described in Articles 57 and 59 in the second and fourth chapters of Article 4 of the Law of the Military). Because of this chain of command from national government to individual soldier, these plaintiffs obeyed the orders of their superiors and did not return to their homes or leave the posts to which they were assigned. These orders were followed not only during the war, but even afterwards when the Kwantung Army promised to provide forced laborers to the Soviet Union. When we consider the socio-political factors behind the Kwantung Army invading the Chinese mainland—and the concomitant problems after the USSR entered the war, when Japanese soldiers were detained by the Soviets—we argue that the Japanese government and the Imperial Army deliberately placed our plaintiffs in harm’s way, especially in life-threatening situations under physically dangerous conditions. We believe this is a typical case of determining who has responsibility, and we can apply fair and equitable legal principles to decide this, as follows:

The government was responsible for the soldiers’ pay (Law of Wages of Military Service), and was responsible for compensation if a soldier died, became ill, or was injured during their service (former Public Officials Pensions Law). These principles as applied to the military were written in Article 1 of the Public Officials Pensions Law—announced in 1937 and implemented in 1938. They “provide[d] allowances for sick and injured soldiers and noncommissioned officers and their families, or the families of the deceased.” We believe these principles—that the nation has an obligation to safeguard its soldiers and their families—is still a national responsibility. The Supreme Court agreed, saying that “this principle of allowances for compensation for accidents in the line of duty is still a government obligation, regardless of how these obligations were practiced in the past … ” (Supreme Court decision, February 25, 1975).

However, in the case of the World War II-era Siberian detainees, the Japanese government not only neglected its responsibility of providing for the solders’ safety, it actively carried out an illegal action by abandoning them to the Soviets. Thus, the Japanese government owes compensations to the plaintiffs for these past actions of ignoring soldiers’ safety.

(3) The Japanese Government Committed an Unlawful Act Under the Post-war Constitution by Not Bringing Draftees Home After World War II

It should be understood—as stated in our filed Action—that the Japanese government clearly broke the law after disarming its soldiers—including our plaintiffs—on August 15, 1945, and offering them to the Soviets as forced labor. It need not be mentioned that these detainees—and our plaintiffs—were in no position to refuse, and could not return home on their own.

Japan accepted the Potsdam Declaration, so the Japanese government was required to disarm its soldiers. But they would also be allowed to return home: “The Japanese military forces, after being completely disarmed, shall be permitted to return to their homes with the opportunity to lead peaceful and productive lives” (Article 9). Since the Soviet Union affixed its seal to the Potsdam Declaration, if Japan asked them to return their soldiers, the Soviets could not refuse the request. Therefore, the Japanese government had some responsibility for the detention of its soldiers. If the Japanese government had acted sooner, there was at least the possibility that the detainees could have returned earlier. On May 3, 1947, the new Japanese Constitution went into effect. Even by this [Allied-imposed] document, the Japanese government was required to request that its detainees be returned. In Article 13 of the Constitution, the rights and dignity of the individual are declared, and their freedom promised: “All of the people shall be respected as individuals. Their right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness shall, to the extent that it does not interfere with the public welfare, be the supreme consideration in legislation and in other governmental affairs.”21 There is no need to mention that returning home is an element of personal dignity and it is the basic foundation of an individual’s pursuit of happiness. If citizens, then, are put into conditions such that these rights are nullified, the Constitution states that it is the government’s obligation to restore them.

Article 22 of the Constitution grants freedom of residence and freedom of travel, as well as freedom for overseas migration.22 I argue that this can also be interpreted as the rights of citizens to move back to Japan. Since the plaintiffs in this case were denied that right by being detained by the Soviets, the Japanese government had a responsibility to bring them back to Japan.

Considering the aforesaid points, I argue that the Japanese government had a responsibility to bring back the detainees as soon as possible, because the stipulations of the Potsdam Declaration and the Constitution went into effect almost as soon as Japan allowed the transfer of its soldiers to the Soviets. However, the Japanese government did not actively negotiate with the Soviet Union to bring them back and, in this, neglected its responsibility (which we have filed under the claim “the Omission”). As a result, our plaintiffs and detainees were prevented from returning earlier.

As an aside, according to the Japanese Constitution, the Ministry of Health and Welfare and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs are placed under the administration of the Prime Minister’s office. Constitutionally, one of the missions of the Ministry of Health and Welfare when it was established was ‘to support repatriates from overseas,” and one of the missions of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs was to “protect Japanese citizens overseas.” In order to pursue these missions one of their duties was to conduct “negotiations with government authorities of other states in order to protect the life and physical safety of Japanese citizens and their property.” They were also to administratively “work for repatriation of Japanese overseas.”

Boatload of Japanese returnees from Siberia to Kyoto prefecture, December 1946.

The subject of the Siberian detainees—whose plight was a product of post-World War II political machinations—naturally was taken up by these missions. Therefore, the repatriation and protection of the detainees was also among the duties of the Ministry of Health and Welfare and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. They were required to negotiate with the Soviets for the release of these Japanese who were detained in violation of International law. It was the duty of these Ministries to make plans to secure their release and put them into practice. However both of these Ministries neglected their duties (as stated in our claim, “the Omission”). It is clear that these actions were illegal, and that they sabotaged possible earlier repatriation of the detainees. Thus, we are asking the Japanese government to take responsibility for compensation for the plaintiffs based on Article 1, Section 1 of the State Redress Law.

Update by The Asia-Pacific Journal:

On October 28, 2009, the Kyoto District Court on Wednesday rejected the damage suit filed by 57 former Japanese detainees who were subjected to forced labor in Siberia for up to four and a half years. More important than the verdict, is the fact that Presiding Judge Yoshikawa Shin’ichi urged the government to take up the issue and resolve it. Judge Yoshikawa pointed out that, “Similar lawsuits have been repeatedly filed as the state has failed to reward the detainees’ efforts.” Kyodo News Agency reports that in a bid to redress the former Siberia detainees’ grievances, the government has decided to seek Diet approval of a bill to provide up to 1.5 million yen in special benefits to them.

The present article focuses on military detainees in Siberia. See earlier articles at The Asia-Pacific Journal describing the plight of civilians left behind in Manchuria, their fate in China, and in the case of some, eventually returning to Japan.

Mariko Asano Tamanoi, Victims of Colonialism? Japanese Agrarian Settlers in Manchukuo and Their Repatriation

Nishioka Hideko, ‘As Japanese, we wish to live as respectable human beings’: Orphans of Japan’s China war

Rowena Ward, Left Behind: Japan’s Wartime Defeat and the Stranded Women of Manchukuo

Mariko Asano Tamanoi, Japanese War Orphans and the Challenges of Repatriation in Post-Colonial East Asia

Murai Toyoaki is the Chief Attorney, Lawsuit for the Compensation for Siberian Detention (link)

Nobuko ADACHI is assistant professor of anthropology at Illinois State University and a Japan Focus associate. She is the editor of Japanese Diasporas. Unsung Pasts, Conflicting Presents and Uncertain Futures. She translated this article for the Asia-Pacific Journal.

This article was originally published in Gunshuku Mondai Shiryō, December, 2008. Rensai Tokushu: Hōtei de Sabakareru Nihon no Sensō Sekinin 40. Baishō Kiso no Hajimari. Shiberia Yokuryū Kokka Baishō Seikyū Kiso. Nihon Seifu no Kihei Kimin Seisaku o Tou. pp. 53-63.

連載特集 法廷で裁かれる日本の戦争責任40。賠償起訴の始まり

シベリア抑留国家賠償請求起訴日本政府の棄兵、棄民政策を問う。

Recommended citation: Murai Toyoaki, “Lawsuit Seeks Japanese Government Compensation for Siberian Detention: The Question of Responsibility for Abandoning Japanese Soldiers and Settlers in Mainland Asia at the End of World War II,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 48-1-09, November 30, 2009.

連載特集 法廷で裁かれる日本の戦争責任40。賠償起訴の始まりシベリア抑留国家賠償請求起訴日本政府の棄兵、棄民政策を問う。

Translator’s Notes

1 Currently, about US $300,000.

2 Currently, about US $100,000.

3 All references are given in Japanese local dates and times.

4 Stalin negotiated the Yalta and Potsdam agreements with Roosevelt and Churchill, establishing, in essence, the structure of the post-war world.

5 There were many Japanese civilians living in former Japanese colonies, especially Manchuria and southern Sakhalin, but also Korea and Taiwan among others. They were there at the behest of the Japanese government, which wanted to colonize its newly acquired territories. Both carrot and stick applied. While pressured to migrate, they were encouraged by economic inducements such as cheap land and relocation bonuses. After World War II ended some 3,000,000 Japanese civilians returned from former Japanese colonies and territories to Japan.

6 This alliance of 1902 was the first of three agreements made between Great Britain and Japan before the First World War. Basically, they acknowledged India and Korea as each other’s spheres of influence, and promised to remain neutral if either nation became involved in a war with one of the “triple” great powers (France, Germany, and particularly, Russia). They were also to come to each other’s aid if war involved more than one adversary. This agreement was critical in allowing Japan to enter the Russo-Japanese War in 1903, as France could not come to the aid of its Russia ally without risking war with Britain. The agreement was cancelled in the 1920s after pressure on the UK by the United States, which feared Japan’s growing naval power in the Pacific.

7 For which the American president, Theodore Roosevelt, received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1908.

8 The Kwantung Army (関東軍, Kantō-gun) was the largest army group in the Imperial Japanese Army. It was also politically influential, especially in the formation of the Manchukuo puppet state.

9 Known in Japan as the Manshū-jihen (満州事変), or the “Manchurian Incident.”

10 Nomonhan is the name of a village on the Mongolian-Manchurian border. This four-month battle is known as Khalkhyn Gol in Russia and the West (from a river passing by the battlefield). Though casualty figures are largely speculative—at least in the tens of thousands—Japan clearly suffered a decisive defeat. Though little known at the time, this battle had strategic importance for World War II. The Japanese would never attack the Soviet Union again, and the loss convinced the Imperial General Staff that the Imperial Army’s plan summed up in the Northern Expansion Doctrine (北進論, Hokushin-ron) anticipating advance into Siberia and Manchuria was set aside in favor of the Imperial Navy’s plan for obtaining resources through the Southern Expansion Doctrine (南進論, Nanshin-ron) that led it to advance into Southeast Asia after Pearl Harbor.

11 Known as the Nis-So Chūritsu Jōyaku (日ソ中立条約) in Japan.

12 Aleksandr Mikhaylovich Vasilevsky (1895-1977), Chief of Staff of the Soviet army, and Deputy Minister of Defense, during World War II.

13 Vyacheslav Mikhailovich Molotov (1890-1986), in many ways Stalin’s right-hand man, negotiated or helped negotiate, almost all the important wartime-era treaties of the Soviet Union, including the Teheran, Yalta, and Potsdam agreements.

14 Satō Naotake (1882-1971) served as a foreign service officer and diplomat from 1905. He subsequently rose to Minister of Foreign Affairs.

15 Known as Nis-So Kihon Jōyaku (日ソ基本条約) in Japan, this treaty normalized diplomatic relations between Japan and the new Soviet government. In it, Japan officially recognized the Soviet government and pledged to withdraw its troops from the northern half of Sakhalin. In return, the Soviets agreed to honor all previous treaties made between Japan and Czarist Russia.

16 These agreements made generous concessions to Japan, granting Japanese subjects fishing rights off the Russian coasts of the Bering Straits and Okhotsk and other places with only a three-mile limit.

17 At Potsdam (July 17 to August 2, 1945), the three victorious Allied powers met to decide the postwar fate of Nazi Germany, which had surrendered on May 8th.

18 Konoe Fumimaro (1891-1945), a former three-time Prime Minister of Japan, was the Emperor’s advisor at this time.

19 Asaeda Shigeharu was the Chief Operations Staff Officer for the 25th Army.

20 Hata Shunroku (1879-1962) was commander-in-chief of Japan’s China Expeditionary Army. He was sentenced to life imprisonment by the Allies in the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal for failing to prevent civilian atrocities committed by Japanese soldiers. He was paroled in 1955.

21 An official English version is given here.

22 The full text states: “Every person shall have freedom to choose and change residence and to choose occupation to the extent that it does not interfere with the public welfare. Freedom of all persons to move to a foreign country and to divest themselves of their nationality shall be inviolate.”