Murakami Tatsuya is the former mayor of Tōkaimura or Tōkai village located approximately 75 miles north of Tokyo and 111 miles south of the Fukushima Daiichi plant.

Tōkaimura is considered the birthplace of nuclear power in Japan since the Japanese government built the first reactor for commercial use there in 1965 in collaboration with British nuclear scientists. As Mr. Murakami reveals below, the Japanese government at the time informed the residents of Tōkaimura only of the building of a nuclear research institute, not a power plant. As time passed, Tōkaimura became heavily dependent on the nuclear industry for its revenue and people’s livelihood. On September 30, 1999, the village had a nuclear criticality accident at the JCO nuclear reprocessing plant. It killed two people, left one person in critical condition, and exposed 667 people to radiation. They were the first victims of a nuclear accident in Japan. Mr. Murakami dealt with the emergency situation as mayor and subsequently became a vocal opponent of Japan’s nuclear energy policy. Since the Fukushima Daiichi Plant accident of 2011, he has been a leading figure in the anti-nuclear movement involving 24 village and town mayors, which calls for the abolition of all 54 reactors in Japan. The interview took place at his Tōkai residence in the summer and winter of 2014.

|

Murakami Tatsuya |

Tōkaimura as a Nuclear Village

HIRANO: Thank you for agreeing to this interview. Let’s focus on issues related to Japan’s nuclear energy policies, the Tōkaimura JCO accident, the Fukushima crisis, and their implications for democracy in Japan.

Tōkaimura’s population is currently 38,000 and its annual budget is 16.6 billion yen. The revenue generated by the nuclear power plant-related business is over 5.5 billion yen, which is roughly one third of total revenue. Considering the plant’s importance in the village economy, some critics say, it is unthinkable for you to have proclaimed an anti-nuclear position and led the anti-nuclear movement as mayor. Could you explain why you made that decision?

MURAKAMI: You correctly note that about one-third of the village’s revenue and operating expense is from nuclear facilities. Actually the budget funds are a bit more than 16.6 billion yen now, 18 billion in total. This year’s budget includes 4.5 billion yen of a financial savings fund that is budgeted for construction of an elementary and junior high school. This amount is added to the budget. So out of 18 billion yen, 5.5 billion yen would be revenue from nuclear-related industries.

We have two thermal power plants here, one of which started operating in 2013. Each plant generates 2.5 billion yen, so a total of 5 billion yen is expected from the thermal power plants. If we don’t include it, it will leave us with about 16 to 17 billion yen in budget. I can certainly say we rely heavily on the nuclear money.

If you look at other local governments with a size and population about the same as the village of Tōkaimura, their average budget is around 12 billion yen. You might wonder if these local governments struggle to provide adequate services to their people. The reality, however, is that there is not much of a difference in terms of the quality of life. In other words, Tōkaimura receives an excessive budget because of the plant. We really don’t need that much. If you have too much money, you tend to do evil. (Laughs.)

Another example of a local municipality hosting nuclear power plants is Genkai-Chō 玄海町 in Saga Prefecture where about seven thousand people reside. Their budget is 7 billion yen while other local governments with a comparable population receive 3 billion yen in budget. You wonder how 7 billion yen enriches people’s lives there, but the reality is that the town has to come up with something unnecessary for the community just to use up the budget, such as building a heated indoor swimming pool, tourist facilities or an impressive gymnasium and cultural center. These facilities were built for a town of seven thousand residents. It means that they are wasting the money. I guess it is “too much of a good thing.”

HIRANO: So it means that Tōkaimura can function well without the revenue from the nuclear power industry.

MURAKAMI: Absolutely! If we didn’t have nuclear power facilities, we would receive local allocation taxes just like other local municipalities. When I was mayor, I spent the budget on the improvement of social infrastructure, such as roads and facilities. It might be true that Tōkaimura may have a slight advantage over other local governments in the areas of welfare and education with extra revenue, but it does not necessarily mean that we can improve the safety and welfare of people significantly.

There are only 20 localities hosting nuclear power plants and related facilities nationwide. Can you believe that there are only 20 out of 1720 local municipalities? If you include Obama City in Fukui prefecture and Rokkasho village in Aomori prefecture, there will be 22. I have to wonder about the legitimacy of the special treatment in the form of subsidies that these 22 localities have been receiving from the joint power of the government and the nuclear industry. Actually, in situations like that, local residents tend to lose their motivation to work hard and do not make efforts to improve their lives. They just depend heavily on what they are given, and the dependency gradually sucks out people’s willpower and capability to think and act for the future of their towns on their own, just like drug addiction. I don’t think it is good at all.

HIRANO: You have been pointing out the aspect of nuclear power as a curse that deprives local community or government of its autonomy and independent-mindedness and leads to total dependency and as a result destroys the community.

MURAKAMI: You could say that. As for Tōkaimura, relatively speaking, it has managed to keep its local autonomy somehow, but once a possibility of nuclear power development is introduced to a local government, we can’t avoid the division between proponents and opponents. There are always people trying to profit by bringing nuclear power plants to their community while others fight the move because of the risks to the environment and themselves. This creates an incredible threat to the unity of a historically harmonious community. The conflict could last 20 to 30 years. Indeed it created a thirty-year human conflict and struggle in some local communities.

HIRANO: Did Tōkaimura experience this?

MURAKAMI: Actually no. In the case of Tōkaimura, the power plants had already been built without our knowledge. (Laughs.) What Tōkaimura agreed to host was a “Japan Atomic Energy Research Institute,” not nuclear power plants. Tōkaimura did not invite nuclear power plants, (laughs) so we had no idea we would end up hosting them. In those days [the 1950s and 60s], the government, the nuclear industry and some Liberal Democratic Party members [like Nakasone Yasuhiro1] and people like Shōriki Matsutarō2, were very enthusiastic about constructing nuclear power plants as a way of boosting national prestige and part of the Cold War strategy. The residents of Tōkaimura merely thought that they would host the Japan Atomic Energy Research Institute, but it turned out that the power plants came along as a part of the project.

It took 30 years for Kaminoseki-Chō in Yamaguchi prefecture as well as Maki-Machi in Niigata prefecture to settle their dispute over nuclear power plants. The same thing happened with Ashihama in Mie prefecture. Kushima City in Miyazaki prefecture once voted against the construction, but then it became clear that Kyūshū Electric Power Co., along with pro-nuclear power activists, has not totally given up the project. It is partly because Kyūshū Electric Power Co. has already acquired the construction site in Kushima City just as Chūgoku Electric Power Co. bought sites in Kaminoseki-Cho and Ashihama. Tohoku Electric Power Co. has also purchased land in the proposed area in Maki-Machi. Recently residents in Kubokawa in Kochi prefecture also voted against the construction plan, but that does not mean that the project became completely invalid. All these communities were bitterly divided and fought against each other for 30 or 40 or even 50 years regarding plans to construct nuclear power plants in their community.

The reason I began voicing concern about safety of nuclear power was the JCO Company’s criticality accident of 1999 in Tōkaimura. The accident occurred two years after I took office. While dealing with the accident, I gradually lost confidence in the government, and I became convinced that this country lacks adequate capabilities to maintain nuclear power plants.

In order to promote nuclear power, the government had kept all problems related to nuclear power hidden by putting a lid on them. But this will cause bigger problems in the future. That was exactly like the start of the Asia-Pacific War when Japan forced people to get involved and moved forward. I’m always conscious of how our country proceeded blindly with World War II. That is to say, it began covering up all negative aspects of history with tyrannical force. There is also the Emperor System to consider. I believe that under the System, Japan held illusions about its ability and failed to estimate reality objectively.

The same thing is happening with nuclear power. The government is promoting nuclear power by perpetuating the myth that nuclear power is totally safe just as during wartime Japan began promoting the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere while hiding from the general public what was really going on. I thought the JCO accident occurred as a consequence of such unfortunate practice, and sure enough, it led straight to the Fukushima Nuclear Disaster.

After the JCO accident, the proponents of nuclear power did everything to suppress concerns and criticisms by further promoting the safety myth. They tightened their organizations, such as Power Reactor and Nuclear Fuel Development Corporation PNC, monitoring management more closely as well as limiting access from outside.

HIRANO: Was it done partly to prevent inside information from leaking?

MURAKAMI: Exactly. I saw this tendency more and more, and felt uncomfortable with it.

|

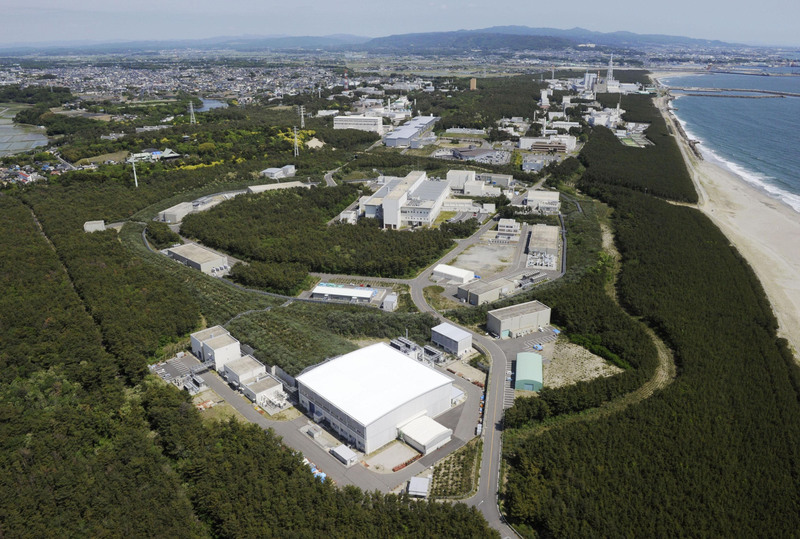

Tōkai nuclear power plants |

HIRANO: Japanese people were made to believe during wartime that the Kamikaze, the “divine wind,” would bring victory to the country and they went along with the wave of the times. Now they are facing a nuclear crisis brought about by believing blindly in the safety myth. You have repeatedly voiced concerns about the similarity between these two historical events as well as their developments.

MURAKAMI: As you know, Prime Minister Abe has been bragging that nuclear technology in Japan is the most advanced or the best in the world. I would say he is blinded by conceit. He is like a frog in a well; he does not know what he is talking about. I am afraid that he is arrogant and overconfident with no knowledge of his own limitations. His vision is so limited to what is going on in Japan that he cannot see the reality of the outside world.

We have a facility called J-PARC (Japan Proton Accelerator Research Complex3) in Tōkaimura. Japanese people praise this Japanese accelerator constructed by Hitachi Ltd. as a product of the world’s best or most advanced technology. I don’t deny that it is an excellent facility, but if you go to Europe, you will find a larger and more powerful accelerator called CERN. When it comes to electronic manufactures, Japanese people tend to think of only Hitachi, Toshiba and Mitsubishi, but there are many others in the world, such as Siemens and Phillips.

I said this at the time of the JCO accident when I was called as a witness by the science and technology committee of the House of Representatives. Technically speaking, it is possible to produce nuclear energy. But the problem is that this country has not established a system to regulate production. In particular, there is no separate organization to regulate nuclear power. I told the committee that it is very dangerous to continue under such circumstances. Japanese scientists might be bright enough to acquire this so-called “mega-science and technology,” but Japan has failed to create a system to control it. That explains why the JOC accident occurred. I have been voicing these concerns since then.

HIRANO: It sounds to me as if the problems lie within Japan’s policy makers and administrative bodies. For example, right after the JOC accident, when you were trying hard to figure out ways to evacuate locals safely and quickly, you could not get straight answers from either the national government or the prefectural levels because they themselves did not know what appropriate measures and actions to take. In the end, you had to come up with solutions by yourself and took actions accordingly. This example shows how unprepared Japan is to deal with a crisis like that.

MURAKAMI: Exactly. The same thing happened with the Fukushima Nuclear Disaster. With no crisis management system whatsoever, residents were forced to follow useless directions while dealing with tremendous uncertainty and despair. The administrative bodies should have created a system for risk management to respond in a way that would minimize radioactive contamination and exposure to locals long before the crisis occurred.

It is just unthinkable that a country like Japan, which is at high risk of earthquake activity, possesses 54 reactors in some of its overpopulated regions, and that there is no place to evacuate in the event of an accident. The government and top officials in the industry have avoided facing reality and have overlooked important safety concerns. Instead of facing the inconvenient truth, they concluded that a crisis was unlikely to occur in Japan.

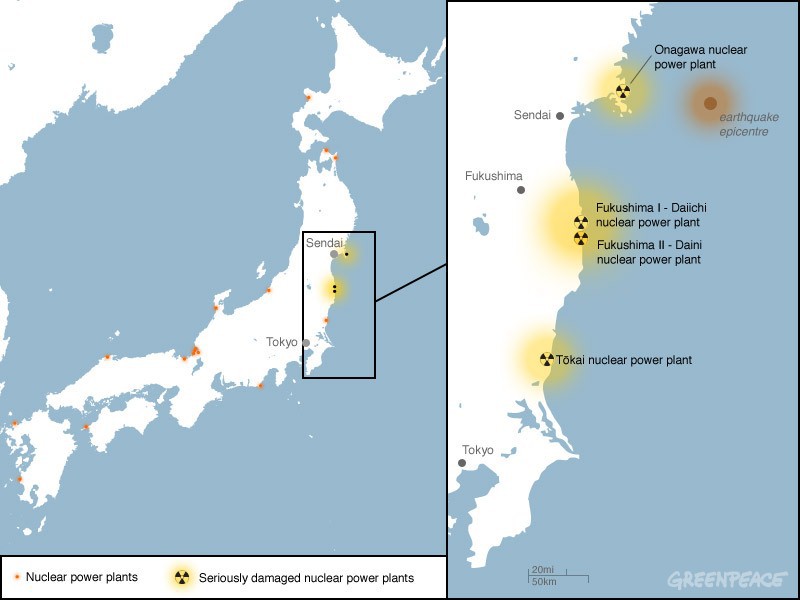

At the time of the Fukushima Nuclear Crisis, the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission responded right away urging Americans within 50 miles of the nuclear plants to evacuate, but the Japanese reaction was very different. Fukushima Prefecture ordered residents within 2 kilometers (1.2 miles) of the plant to evacuate. Later this was extended to 3 kilometers (1.9 miles,) while residents within 10 kilometers (6.2 miles) were instructed to stay inside before the evacuation order was extended to 20 kilometers (12 miles.)

Fukushima, Tōkai and Nuclear Policy

HIRANO: Both governments reacted to their respective nuclear disasters based on the same information, but the outcome was so different. How would you evaluate the different reactions of two governments?

MURAKAMI: I believe the U.S. government got the same information at that time. But the population affected was much smaller, which made the move easier and quicker. The Japanese government was dealing with tens of thousand people in the affected area, so unless they had been prepared, it would be difficult to act effectively. In fact, they did not even have planned evacuation routes or procedures for emergencies. The government’s utmost concern was to avoid panic among the residents. I’m sure the government officials panicked themselves, but they absolutely did not know what to do because they were unprepared to deal with such an emergency.

They were like, “What! Isn’t there more than one route for evacuation?” Before the accident, the implementation of emergency evacuation measures had not even been part of nuclear disaster prevention plans. In Japan, disaster prevention policies were originally written based on the premise that radioactive contamination and extensive radiation exposure would never become an issue because of the multiple forms of protection installed around the nuclear power facilities.

The publication of emergency evacuation plans would lead to questions and concerns about nuclear safety, so this was not even considered. According to the safety design regulatory guide for nuclear reactors, severe nuclear-related accidents would not occur in Japan because the power supply would be restored within eight hours of a station blackout. Before that, the emergency diesel generator would operate the isolation cooling system to provide enough water to safely cool the reactor until external power was restored. Based on the assumptions of the regulatory guide, there was no need to implement evacuation plans for residents.

This mentality reminds me of wartime Japan. They said that there was no need to think about being a prisoner of war because Japan would never lose. Don’t even think of becoming a captive. Before being humiliated as a prisoner, give your life for your country. I feel it is the same. I mean I see authoritarian power … well … the fragility of society.

HIRANO: There seems to be a lack of customs or habits in Japanese government and politics to make clear where the prime responsibility lies. For example, they built nuclear power plants, but they never thought through who would be responsible and how they should act in a crisis. All they did was build plants and focus on the benefits they would bring. That’s why Japan built 54 reactors on such a small and densely populated island.

MURAKAMI: That’s right.

HIRANO: Did you experience such irresponsible responses from government officials and representatives from the industry in the aftermath of the JOC accident?

|

JOC accident |

MURAKAMI: What bothered me most was the fact that they closed the case without even trying to reflect thoroughly on the real cause of the accident. The explanation they came up with was that the workers had failed to use proper tools and equipment. They used the bucket and ladle rather than the dissolving tank to mix 18.8% enriched uranium oxide and nitric acid. Of course, the public was shocked to hear that and was easily convinced that the accident had been unavoidable under the circumstances.

But the real problems lay elsewhere and no one seemed to pursue it. The real problems were that they built the very small and potentially hazardous fuel preparation plant to deal with 18.8% uranium, while no major civil reactor elsewhere uses uranium enriched beyond 5% in residential areas, and the plant was not adequately designed to prevent the possibility of a criticality accident.

Moreover, they had inspected the plant only once since it began operation and failed to do a routine inspection for seven or eight years after that. Not only that, but the Power Reactor and Nuclear Fuel Development Corporation, which is the company JCO received the contract from, did nothing to supervise the operation. Even after the accident they left their responsibilities vague, concluding that the cause of the accident was “human error and serious breaches of safety principles” as exemplified in the use of the bucket and ladle. They claimed that it was a rare incident that was isolated from the mainstream workings of Japan Atomic Energy Research.

Now let me explain what was going on in the reactor in Tōkaimura at the time of the Great East Japan Earthquake. You might have heard that the tsunami wave almost spilled over the 70 centimeters (28 inches) protective seawalls, but seawater did enter into the pump chamber, narrowly avoiding reaching the ceiling by 40 centimeters (16 inches).

Inside the chamber, there were several seawater pumps intended to cool an emergency diesel generator, but one of the pumps was submerged under seawater and was not able to cool the generators sufficiently, so one of the three generators failed. We were very close to a station blackout.

With insufficient cooling power, the pressure of the reactor core rapidly increased and too much vapor was released, which prevented cooling water from entering. There is something called a main steam relief valve that is usually motor-operated in order to isolate the steam source from the turbine. Not being able to operate it properly or fast enough with the motor, technicians ended up operating it manually as many as 170 times. At the last stage, the valve was left open for a long time in order to keep the cooling system going. We nearly faced a station blackout.

Also, just one week prior to the earthquake and tsunami we finally completed construction to raise the height of the tide wall, and it was only two days before the earthquake when we finally closed the entrance path for the construction workers, which was a big gap in the wall. We were really lucky.

HIRANO: I read about it and realized how close Tōkaimura came to being as disastrous as Fukushima. We can say that it was a near miss. If a hydrogen explosion had occurred at Tōkaimura, the entire Kanto region would have been doomed, wouldn’t it?

MURAKAMI: There are 14 reactors on the shoreline from Onagawa in Miyagi prefecture to Tōkaimura, and I wouldn’t have been surprised if all these reactors had ended up failing in some way or another.

HIRANO: You mean that they were all dealing with similar dangerous situations?

MURAKAMI: Exactly. For example, Onagawa lost 4 out of 5 external power supply lines and the only one left barely managed to supply power to its nuclear power station units 1, 2 and 3. Fukushima’s No. 2 facility was in the same situation. All four reactors, 1-4, lost their external power supply to maintain the heat removal system, but reactor 3 quickly recovered to retain its function to stabilize other reactors. Then workers also had to restore power by laying more than five miles of heavy electrical cables by hand.

Of course if Reactor 4 at Fukushima No.1 had suffered more damage, there would have been no chance to save the Fukushima No. 2 facility. If it had failed, the Tōkai No. 2 reactor would have been severely damaged. It would have been like a chain reaction.

It tells you how catastrophic it could be for a country like Japan to house nuclear power plants. While about 150,000 people or so were living within 20 or 30 kilometers of the Fukushima No.1 plant, there are one million people living within 30 kilometers (18 miles) of the Tōkai plant and 750,000 people within 20 kilometers (12.5 miles).

HIRANO: It is unthinkable that they built the plant in an over-populated area like that.

MURAKAMI: It is crazy. Right now about 130,000 people in Fukushima have been evacuated from the exclusion areas, although it would be 80,000 or 90,000 people if we do not count voluntary evacuees. As far as Tōkaimura goes, the number of evacuees would be at least 10 times that of Fukushima, actually, it might be 20 times.

HIRANO: What if you include voluntary evacuees?

MURAKAMI: Yes, if we include them, it would be estimated at 1.5 or 1.6 million people. Who would guarantee the livelihood of these people?

HIRANO: It would be hard. The government would go bankrupt.

MURAKAMI: Also there are many Hitachi manufacturing divisions and plants in this area, and it is impossible to compensate for damages to the company. They are estimating that it would cost 5 trillion yen to compensate for 80,000 people, so it is absolutely impossible to think about compensating for the damage caused by Tōkaimura No. 2, even with state compensation. It means that victims of a disaster at the Tōkai plant would have no choice but to drop the case altogether. They wouldn’t be able to expect anything.

HIRANO: I don’t think it would be an option to find a place to relocate that many residents at once, either.

MURAKAMI: I don’t think so, especially within this country. If it were possible, they would have relocated the victims in Fukushima by now. Speaking from the examples of Chernobyl, Fukushima should have been declared uninhabitable, especially to raise children.

HIRANO: I agree. Mr. Koide Hiroaki of Kyoto University4 claims that it does not solve anything just to give money to the victims. At least families with small children should have been given new land somewhere safe to start their lives again. The government should have provided them with a new village and community to live.

MURAKAMI: But I don’t know if we can find such a place in this country. In fact, I thought about the possibility of relocating the entire Tōkaimura myself. The news about the Fukushima crisis chilled me to the bone. As I mentioned, we were so close to having a similar situation, so I started thinking about relocating the entire village and in fact found a place in Hokkaido. (Laughs.)

HIRANO: Hokkaido, is that right? (Laughs.)

MURAKAMI: Yes, I thought about the possibility of relocating 38,000 residents and have them start dairy farming and cultivating new land in Hokkaido. I know it should not cost as much to buy land there as in Tōkaimura. I even visited the area. If it doesn’t work, I thought, other alternatives would be Australia or our sister state, Idaho. (Laughs.) Of course, we would first need to acquire water rights there, but we could start working on an irrigation system in the desert. It is exactly the land cultivation project of the 21st century. But it is often the case that mass relocation like this would face discrimination in the new land. (Laughs.) If we are relocating with one or two people, we would be welcomed, but a mass relocation would be different no matter where.

Actually this is a serious matter in the sense that Tōkaimura alone cannot come up with some kind of solution if an accident occurs at the Tōkai No.2 reactor. All neighboring communities, such as Mito city, Hitachi city and Hitachinaka city, need to be involved in the decision over what to do in a scenario like that.

|

Struggle for Local Autonomy

HIRANO: Do you have any communication or collaboration among the neighboring cities and villages?

MURAKAMI: Yes, we do. With Mito city [the capital of Ibaraki prefecture] in charge, we’ve formed a central district chief committee 県央地域首長懇話会 with mayors from all local municipalities as far north as Tōkaimura and as far south as Omitama city. Also, after the Great East Japan Earthquake and the subsequent nuclear power plant accident, I organized a committee with mayors from five adjacent municipalities surrounding the nuclear power plant in Tōkaimura, including Hitachinaka city, Mito city, Naka city, Hitachi city and Hitachi Ohta city.

According to the safety agreement with Japan Atomic Power Company, the Tōkai nuclear reactor could resume operations as soon as the company obtains approval from both Tōkaimura and Ibaraki Prefecture, but now these adjacent municipalities are demanding a part in the decision-making process. It is quite understandable because they would receive as much damage as Tōkaimura. The population of Hitachinaka city is about 160,000, and Naka city has 60,000 to 70,000 people. The mayors in Naka city and Hitachinaka city are working hard for it.

HIRANO: So are these local governments clearly expressing opposition to bringing the nuclear reactor back on line?

MURAKAMI: Well, not explicitly. Tōkaimura has a new mayor now, but I think he and I share similar opinions. As you know, these mayors are not totally free to say whatever they want. They need to take their political position and situation into consideration, such as future elections and various positions of the political party they belong to, so they would rather leave the issue vague in order to avoid political conflict. (Laughs.) But the mayor of Hitachinaka city, Mr. Honma, has expressed his opposition openly. The mayor of Omitama city explicitly said no to restarting the reactor. He himself is a dairy farmer. And the former mayor of Shirosato-cho and of Ishioka city, which is not a part of the committee, also expressed his opposition. It is the same with the mayor of Hokota city, whose main industry is agriculture. The mayor of Ibaraki-machi stays rather vague because its neighboring town, Ōarai-machi, is highly dependent on nuclear power. In fact, the industry is tactful in enticing mayors.

HIRANO: Do you mean that a mayor might be getting large “donations” from the industry during the election?

MURAKAMI: Hmmm, I don’t think that is the case here in Tōkaimura. I don’t believe that is the case with Ōarai-machi either, because in Ōarai most city council members are associated with the Japan Atomic Energy Research Institute (JAERI) and Japan Atomic Energy Agency (JAEA) anyway. I don’t think political donations are the issue. I would say their influence is not from money but the way they approach local government. They are very polite and humble. You know, these top elite scientists with a PhD are graduates from prestigious schools like Tokyo University, but they never act arrogantly. If these respectful, elite gentlemen come to see you and ask for a favor, I can see how it could be sometimes hard to say no to them.

When I was still mayor in Tōkaimura, I received a request from the Japan Atomic Power Company (JAPC) to build unit 3 and 4 reactors, but I was not enthusiastic about building additional reactors. At the time of the Tōkaimura nuclear accident in 1999, the plan to build J-PARC (Japan Proton Accelerator Research Complex) had already been finalized and the construction had begun, so after the accident I decided that we should end the dependency on nuclear money as a way for community building and development, and that we should focus more on becoming a research-oriented community.

That’s how the concept of “Tōkai Science Town” was born. This was something we had been discussing even before the Fukushima Disaster. Since the completion of J-PARC, I have spoken about this on various occasions as “the dawn of a new era for Tōkaimura.” Of course, we will lose a host of subsidies, property and income tax revenues.

Some might think that all we need is to invite facilities or industries that bring a lot of financial resources to our community. Such logic seems to me too simple. I wanted to free us from dependency on so-called easy money.

Judging from how the Japanese economy has been changing, I could tell that the new era has come. For Tōkaimura we should shift direction and create our community utilizing social and cultural values that J-PARC would bring. I have been saying this since a few years prior to the Fukushima nuclear accident.

First, we came up with the idea of “Tōkaimura Advanced Science Research Cultural City” 東海村高度科学研究文化都市構想. I intentionally included the word “culture” in it. I believe we came up with this concept around 2003 or so, but we did not move forward with it until about 2010 when we organized a committee to work on a concept for a science town. We had our first meeting in June. At that time, I knew that nuclear dependency would eventually lead to a dead end.

Under the influence of Abenomics5, Japan is mainly focusing on GDP expansion, but I know that this will end soon. In order for local communities to survive economic downturn, I believe that we need to work together to depart from the GDP expansion principle and obsession with economic developmentalism. We need to focus more on primary industries like agriculture and the craft industry or welfare. If we strengthen these areas, I know our town will attract a lot of people to settle in our community. I have been advocating this for quite a while even before the Fukushima accident.

HIRANO: Why did you include the word “culture” in the new concept for Tōkaimura.

MURAKAMI: I wanted to emphasize that what we are trying to create for our community is not all about money.

HIRANO: So, it is not money but culture or rather what people create and value. If it is only science without culture, people in general might associate Tōkaimura with the money or profit that science and technology could bring in.

MURAKAMI: That’s right. The first thing that could come to mind might be money when we are planning the future of our community, but I wanted to emphasize that money and numbers alone cannot make us happy. I don’t think it is necessarily true that people with income of 5,000,000 yen a year are much happier or have a better life than those who earn 3,000,000 yen a year. I really don’t think so.

Many people ask me what I am going to do to maintain the economy if I abolish the nuclear power plants. First of all, I am not really certain that nuclear power would really enrich our lives. This is a brochure that someone put together explaining what directions we would like to take in the future to recreate our community. This does not necessarily reflect exactly what I have in mind, but states that we need to depart from an economy-focused or growth-oriented society and that it is time to establish local autonomy.

Instead of pursuing economic gain, we should focus on how to increase cultural value and social value in our lives by utilizing what we already have or by creating something new by applying our wisdom and experience. For example, we have J-PARC here in Tōkaimura and we can make that our asset. We have about 100 to 150 visitors from overseas at J-PARK every day, and we have about the same number of people from all over Japan. So we need to create a community to welcome and accommodate these people.

HIRANO: I’m very interested in your concept of local autonomy. Generally speaking, local autonomy implies a sense of being closed or exclusive, but what you are advocating here is rather to open a door to the world and contribute to transnational interaction by utilizing local assets and features.

MURAKAMI: Exactly. In 2011, before the Great East Japan Earthquake occurred, we organized a meeting to talk about the basic philosophy, goals and concept for the future of our community. We called it the Tōkaimura 5th Comprehensive Plan. About 150 residents showed up and the basic philosophy they created together was “community building that reflects residents’ wisdom and knowledge for all living things in the present and future.” The plan elaborates on this philosophy in the following way: 1. we will create and pass down the wisdom that enables us to learn from the past, reflect on the present, and build the future; 2. we will use villagers’ wisdom to create together a society that treats every individual with respect and also provides her/him with various opportunities to fulfill her or his life; 3. we will respect the harmony and connectedness of nature and life and gather all our wisdom to create a community filled with vitality that generates new ways of living. They came up with this idea all by themselves as the future goal for Tōkaimura.

HIRANO: It is really impressive, isn’t it? I wish every local government would adopt this democratic process for community building. Did they meet multiple times before they finalized their plans?

MURAKAMI: Yes, and I did not make any suggestions to them as mayor. Interestingly enough, what they came up with perfectly matched what I had in mind. I think that it proves that my concern that “Abenomics” prioritizes economic growth is widely shared by citizens. It seems natural that people have started questioning the direction in which Abenomics is leading the country.

HIRANO: We can say in some sense that nuclear power is a symbol of an economy-focused society.

MURAKAMI: Exactly. It is a typical example. Usually nuclear power plants are built in impoverished rural areas, and local communities become heavily dependent on the money nuclear plants bring them.

Speaking of Tōkaimura, we have a lot of inns, but rather than being for ordinary travelers, they are for nuclear power plant workers, so the accommodations are quite simple and shabby. They only eat and sleep there, often sleeping in one big room together and sharing a bathroom. (Laughs.) Of course some of the inns are called “business hotels,” but if regular customers stay there once, they won’t want to stay again. (Laughs.)

When we had completed J-PARC, I suggested that the inn owners renovate their rooms to accommodate researchers and students who were coming to visit the facility from all over the world, but they refused, saying “No, thank you.” They said that it is too much trouble especially having visitors from overseas. They can operate their businesses fine. They are not motivated to do anything extra.

HIRANO: Do these owners also support nuclear power?

MURAKAMI: Sure. Some of the inns are even located in the middle of a rice field. When I first became mayor, I did not understand why there were inns in the middle of nowhere, but then I gradually came to understand.

HIRANO: Nuclear dependency has created a kind of distorted structure in the local community.

MURAKAMI: Exactly. Indeed, we have a lot of inns everywhere in this town. While there are some within one kilometer of the power plant, some are located in places that do not make sense, for example in places where you can’t even catch a taxi, instead of near the train station or downtown. They are all for the plant workers, and the inn owners can make a decent living off of it. The nuclear power company has a contract with these inns, so the owners do not have to do anything to attract customers. They can do good business without any effort. The same goes for stationery stores and clothing stores in Tōkaimura. They don’t do business with residents, because they don’t need to. The nuclear power company’s branch offices buy their goods regularly, so these businesses are stable and secure without extra work.

HIRANO: That’s precisely what nuclear dependency means, doesn’t it?

MURAKAMI: Exactly. It is called dependency not only financially but also mentally. The population in Tōkaimura is growing with young families moving into town. We have a lot of babies, but business owners have no interest in them, even though I suggested that they target young families.

HIRANO: In this structure of dependency, you can’t cultivate and grow other local businesses that would accommodate needs of residents.

MURAKAMI: That’s right, as long as our industrial structure disproportionately depends on nuclear-related business.

HIRANO: I see. I can imagine you must have dealt with a lot of criticism when you began advocating for the new town concept.

MURAKAMI: I do not personally remember having heard much criticism, but I am sure there were complaints about what I was advocating, and also there were people who were hoping that I would lose the next election.

Anyway, I am skeptical that under the influence of the nuclear industry we will succeed in cultivating other businesses independently. Construction companies and machine processing companies are fine as long as they keep ties with the nuclear power industry. In other words, they are no longer competitive. Right now, however, operation of the Tōkaimura reactor is suspended, so business owners won’t be making money and they may go out of business.

HIRANO: Futaba town6 in Fukushima, which was once a declining town, was also trapped in a vicious cycle by continuing to build reactors in exchange for substantial subsidies from housing nuclear power plants.

MURAKAMI: That’s right. Futaba had once struggled financially so badly that it was designated for fiscal consolidation. When the town reached the brink of bankruptcy, it again turned to Tokyo Electric for financial help and approved a plan to build two new reactors, No.7 and No. 8. When the town began to recover, the Fukushima disaster occurred, and the evacuation of the entire community followed. I remember back then, the town’s former mayor Mr. Idogawa was working desperately to bring nuclear plants to the town. But now he has become a vocal critic of nuclear power. He himself was forced to evacuate to Saitama and has not been able to return.

Now let me talk about the reaction I received from the residents in Tōkaimura after I began opposing nuclear power. Although some of them might have been hoping that I would lose the following election, I did not really experience protests or personal attacks. Most of the residents I dealt with at that time were very supportive of me, although I am sure behind my back there were a lot of people who fiercely opposed what I was standing for. I also got a lot of support and encouragement from former or retired employees at Hitachi Ltd. and Atomic Energy Agency.

HIRANO: You mentioned earlier that issues of nuclear power plants often divide a town. Did you also see the problem among the city council members in Tōkaimura?

MURAKAMI: Yes, they were divided in half. At first, not a single council member clearly opposed nuclear power, but after discussing a petition for decommissioning the Tōkai No. 2 reactor with our nuclear special committee for a year or so, some members began making their anti-nuclear stance clear. They are not the majority yet, but I would say about half of the council members oppose nuclear power now. I can say the same thing about the residents. About half of them are anti-nuclear while the other half supports it.

HIRANO: What made you decide to run for office? Is it because you had visions for the town?

MURAKAMI: I wouldn’t say it was mainly for my hometown although I was hoping to be able to do things to eventually benefit the town. One reason why I began thinking of running for office was that in 1997 the decentralization promotion committee issued the second recommendation. It stated the basic concept of autonomy for local governments by giving administrative authority and responsibility as well as legislative power to local government. I knew that the era of political decentralization and shifting power from the long-standing centralized government to local government would be coming. This hope eventually made me enter politics.

Of course, I wanted to change the way the local government had been operating here. I had been observing that local governments always turned to prefectural government, and prefectures turned to national authority. Simply speaking, a prefecture is nothing but a national government agency, but local governments all turn to it. All local officials thought about was how to get things done through petitioning the central government. Instead, I wanted to get townspeople involved in the process of creating their own community by putting them in charge. I found it very rewarding to lead, and I also wanted to change the way the local office would operate by staffing it with new officials. That was my ideal.

HIRANO: Did you also think at that time that you would like to change the way the local economy had been working for Tōkaimura by shifting from nuclear dependency?

MURAKAMI: Actually I did not have that vision yet. Tōkaimura was financially well-established, so at the beginning I thought anything would be possible as long as we put in effort. Then we had the JCO accident within two years after I took office. While struggling to find a way to pull our town together and recover from the accident, I decided to turn to the city of Minamata7 for help. I visited there and met the mayor and residents. They taught me a lot. In those days, people just believed that the only way to develop local towns was by getting help from the central government or bringing large corporations to the area, but I learned from Minamata that we rather need to break away from the old mindset focusing on economic growth and development and create a sustainable society, focusing on and paying more attention to protecting the environment and respecting human beings. In that sense, Minamata was my starting point.

HIRANO: It is almost ironic how history is repeating itself. A similar set of problems to what Minamata had suffered arose after the Fukushima accident.

MURAKAMI: That’s right. Exactly.

HIRANO: It means that lessons learned from Minamata need to be applied in order to deal with the situations people in the larger Fukushima area are facing now.

MURAKAMI: You are right. I also see that if we keep depending on Abenomics, local towns and cities will decline rapidly.

HIRANO: So you mean that sort of Neo-liberalism?

MURAKAMI: Neo-liberalism, that’s right. I thought about this at the time of the Koizumi administration (2001-2006). This is how Prime Minister Koizumi thinks. Why are you living in such a remote mountain or on an isolated island? It costs too much to support you, so move out from there. I will give you three or four hundred thousand dollars so that you can live in a city. It’s cheaper. If you stay in such remote areas, we have to fly a helicopter to get you to a hospital when you get sick. It costs the government too much money. (Laughs.) That’s what I call Neo-liberalism.

HIRANO: They cut off everything local.

MURAKAMI: Cut off, cut off. That exactly happened with the merger of cities and villages. It was the Great Heisei Mergers.8

HIRANO: Koizumi planned to establish small cities in local areas through consolidation and eradicate “useless” rural communities to achieve maximum economic efficiency.

MURAKAMI: That’s right. He wanted to get rid of them, claiming it would greatly improve economic efficiency for the country. That was what Koizumi’s reform efforts were all about. And the trend has been accelerated by Abenomics now. Mr. Masuda Hiroya, a close associate of the Abe government, published a rather disturbing statement that about half of Japan’s regional cities may disappear by 2040. I don’t believe it would happen because the theory is based exclusively on economic rationality. When we think about economic rationality and people’s values, they may conflict.

What national wealth means is, as the court rulings of the Ohi nuclear trial states, that people live in a rich land and the people’s livelihood should be enriched by it. That’s what national wealth should mean, but the idea of economic efficiency comes only from the perspective of monetary wealth.

“National Policy” and “Natural Disaster”

HIRANO: Let’s talk about the concept of “national policy” (国策). In your book, you talk about how the concept plays a psychological role in people’s mindsets. I was impressed with your keen insight.

MURAKAMI: It is said that nuclear energy policies were implemented as a national policy, but it is not clear who actually decided this. It is true that the government has been in charge of its promotion, but I have to wonder how much the opinions and feelings of residents or local governments that house nuclear reactors have been taken into consideration under the name of national policy.

Then I looked the word up in a dictionary, and found that the term “national policy” is associated with colonialism. According to the Kōjien dictionary, the colonial powers created national policy in order to control and promote the development of colonies. I indeed thought it explained well the true nature of national policy. The term is self-explanatory; in other words, it is a policy adopted by the government.

There are many policies that fit under that category, but only few are given the title of “national policy”. I believe nuclear energy policy alone is referred to as a national policy nowadays. Mass media still often uses the term without hesitation, but it is only during wartime when the term “national policy” is clearly applied. For example, Basic National Policy Guidelines9 and Imperial National Policy Guidelines10 during the Asia-Pacific war – they are all associated with war.

HIRANO: That’s right. National policies implies mobilization of the whole country; that is the premise.

MURAKAMI: Exactly. In that sense, national policies mean that people are forced to make sacrifices for their country. In other words, it is for a greater cause and that’s why it is a virtue to dedicate one’s life to their country. The term “national policies” implies this, doesn’t it? Even though it is an era of decentralization of power, some people in local areas regard nuclear energy as a national policy and dismiss their opponents as people who are against national policies. We still have people like that in Tōkaimura nowadays.

Even some of the local government chief officers, especially ones hosting nuclear power plants, say they are hesitant about speaking out against or even making decisions on nuclear power themselves, because they are national policies. It seems to me all they are doing is avoiding their responsibility. Saying that it is something the government decides, they keep silent about whether or not nuclear plants should be reactivated. The central government also tries to silence local governments in the name of national policy. This is how national policy works.

HIRANO: It is the most anti-democratic approach, isn’t it?

MURAKAMI: Exactly. It’s the most anti-democratic way. It is just like the Liberal Democratic Party’s draft constitution. (Laughs.) According to it, the government matters most, not the citizens. I think the mass media should really expose the fact that nuclear energy policies are anti-democratic.

HIRANO: Now let’s talk about another problematic language – natural disasters and man-made disasters. I heard that it is commonly accepted in Japan to treat the Fukushima nuclear accident as a natural disaster. People say that this kind of large earthquake does not occur often, maybe only once every thousand years, so there was nothing we could have done to prevent the disaster, and we should just move on.

MURAKAMI: It is actually dangerous to think that way. They say only once every thousand years, but that means it may happen every thousand years. It seems to me that it is very high frequency. And although they say only once every thousand years, there was the huge trench-based earthquake off Indonesia’s Sumatra Island in 2004 and in Chile in 2010, as well.

Around 2006, we had background checks for earthquake resistance on the nuclear power plant in Tōkaimura, but they were mainly concerned about the active fault due to the Niigata-Chuetsu Earthquake of 2004. So I told them that the Japan Trench is lying right in front of us within 150 kilometers off the coast, and asked them if this posed a safety concern to us, considering what had happened at Sumatra Island. They said there was no need to worry about it because the Japan Trench lies where the pacific plate subducts smoothly beneath the continental plate, unlike off Sumatra Island, so energy won’t be accumulated. They assured me saying we would not experience a huge earthquake like the Indian Ocean earthquake here in Tōkaimura. They are employees at a nuclear power plant who are in charge of earthquake resistance Although it is said that earthquakes like that may happen every thousand years, they are happening more frequently. For some reason, someone made this theory based on the Jogan Earthquake of the year 869. I don’t believe it.

HIRANO: In fact, there was the Hōei Earthquake in 1707.

MURAKAMI: You are right. There was 1855 Edo Ansei Earthquake, as well.

HIRANO: Exactly.

MURAKAMI: Of course, we can’t forget the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923. Anyway, the claim that it only happens once every thousand years is just deception. Even if it were true, we should not think that there is nothing we could do. We build nuclear reactors on the earth and in nature. It means that we should expect that something unpredictable and beyond human ability might happen. They might also blame the tsunami for the Fukushima disaster, but how can they say that after building nuclear reactors on an earthquake-prone archipelago? I believe that once an accident happens with nuclear power, there is no going back. We are doomed. This should be the scientific spirit.

HIRANO: In some sense, the fact that it was “unexpected” should not be an excuse.

MURAKAMI: That’s right, because we are the ones who created something that should not exist to begin with. As you know, the atom does not exist in nature, but we manipulated the nucleus inside an atom and opened up a Pandora’s box, so we should have prepared for risks and taken measures to respond. That is what is called the scientific spirit, I think. That’s why I believe that it is nothing but an excuse to define the Fukushima nuclear accident as something “unexpected.” It is a man-made, not a natural, disaster.

Elite and Cover-up Culture

HIRANO: What about the prevalence of cover-ups? What do you think of this tendency among elites in Japanese society?

MURAKAMI: This has something to do with the widely shared elite mentality. They honor self-sacrifice for the “greater good” or “common good,” which includes sacrificing your own life. You see it from how military officers acted and treated people during pre-war and wartime Japan. They didn’t hesitate to sacrifice citizens’ and soldiers’ lives in the name of the Emperor and in defense of our country. It is also true that they were driven to act this way for self-protection. I wonder how many citizens have been abandoned in the past.

There were Japanese civilian settlers who the Japanese government dispatched to what was then Manchuria. In the end, many of them, including children, were abandoned after the war. The Japanese Army heard about the Soviet Red Army crossing the Manchurian border, but did not let the settlers know about it. The Japanese Army rapidly retreated to the capital, Shinkyo (today’s Changchun), leaving the settlers behind. Millions of Japanese civilians were abandoned.

In fact, things like that happened not only in Manchuria but also on Saipan where Japanese civilians, who had lived on the island, were forced to fight against American soldiers. Worse than that was the battle of Okinawa. The Japanese military used civilians in Okinawa as a shield for the defense of the mainland and sacrificed their lives. Then it launched preparations for the final decisive battle, where the one hundred million people of the Japanese empire were expected to fight as one. For Japan’s leaders it was more important to not lose face before their superiors, as well as to protect the emperor, than to protect hundreds and hundreds of thousands of lives. This explains the reality of Japanese elites.

As for Fukushima, they tried to hide information from residents in Fukushima. Elites from the Fukushima Prefectural Government did the same thing. They did not hesitate to put residents in danger in order to protect their organization. We see such people in big corporations as well.

HIRANO: I see. The commitment to the greater good that Japanese elites value means, in the end, abandoning or discarding citizens. They are also protecting themselves.

MURAKAMI: Sure, their only purpose is to protect themselves including their social status and their organization. You surely will be kicked out if you dare to question them or even mention that they might be risking people’s lives. If you were to speak up, you would need to prepare for the consequences. We can say the same thing about the nuclear industry in Japan. A pyramid of power has been established in which graduates of Tokyo University reign at the top. All they care about is how they are treated in the organization and society, just as government officials do.

Constitution Matters

HIRANO: Let me ask you about the Constitution, in particular your view of the importance of individual freedom and human dignity. The Abe administration has been questioning its value and validity. And I think this issue is deeply interconnected with the way the administration deals with the disasters caused by the Fukushima power plant explosions.

MURAKAMI: During our education, we learned about the Constitution superficially. Freedom of speech or academic freedom was an object to memorize. But understanding it from a historical perspective is crucial. For example, Articles 31 to 40 explicitly forbid abuse by the police and state authorities. We need to think about why these articles were written so explicitly. It is because there had been a series of laws designed to suppress dissent in pre-war Japan, such as the Public Order and Police Law of 1900 and the Public Security Preservation Law of 1925. Under these laws, human rights were suppressed and brutally crushed by the full power of authority.

That’s the background of how criminal justice has been established in the Constitution, and that’s the reason why the Constitution describes each article in such detail. For example, Article 33 states that no one shall be apprehended without an arrest warrant issued by a competent judicial officer. Article 35 includes the right of protection against unusual searches and seizures, and the right to remain silent is guaranteed by Article 38.

I also realized the importance of Article 13 while holding public office and dealing with social welfare policies and services. It states that all people shall be respected as individuals. As you know, the Liberal Democratic Party has criticized individualism, saying that it has introduced the idea of selfishness to Japanese society and families and destroyed unity, but I realized while I was in office how crucial it is to look at every single person individually for purposes of social welfare and services. Recently I came across an article written by the late Hisada Eisei. He was a Constitutional scholar at Hokkaido University of Education who was deployed to Luzon in the Philippines during World War II, although he tried to flee the battlefield and never engaged in combat. In his book he describes how emotional he became when he saw Article 9 aboard the repatriation ship, and he claims that Article 13 is the fundamental principle of the Japanese Constitution: respect for human dignity.11

HIRANO: You have pointed out in your writings that Abe pushes his various policies by taking advantage of the criticism of individualism. He also often talks about his new defense and foreign policy doctrine, what he calls “proactive pacifism,” claiming that it will enable Japan to play an assertive role in promoting regional stability as an active contributor to peace and will bring more protection to individual rights and serve the nation in the long run.

What he is actually saying, however, is that individuals or his interpretation of individualism should be sacrificed for the interest of the nation. The nation or society comes before people. That’s what pacifism means to him. You are taking a diametrically opposite stance trying to understand what individualism really means, aren’t you?

MURAKAMI: That’s exactly right. If the nation does not exist, Abe claims, you will lose your life and freedom. What I believe is that individuals come first before the nation. When the nation or the government comes first, it will seize absolute power to control our lives as the wartime military has very well demonstrated. I argue that the nation should be built based on the principle of basic human rights, such as individual freedom and dignity. Abe speaks as if all of Japan’s neighboring nations are going to attack us. What he is trying to accomplish is the creation of a climate of fear.

HIRANO: Yes, by purposely stirring up nationalistic sentiment against China and Korea.

MURAKAMI: Exactly.

HIRANO: The Liberal Democratic Party has benefited greatly from tensions and disputes they provoke.

MURAKAMI: Although Abe said that he was open to starting a dialogue with China about the Senkaku islands, he did not take any actions to negotiate when Chinese patrol ships entered waters near the islands.

HIRANO: He made it clear that for Japan the question of ownership was not open to negotiation.

MURAKAMI: He has often said that we need to “bring back Japan” or “depart from the postwar regime”, but he uses these slogans to justify his policies. That is why he does not want to negotiate. He does not visit, nor does he send anyone to have a talk with China’s Coast Guard to prevent further accidents. As we know, Abe and his administration’s objectives have been to revise the Constitution and to over turn the postwar regime. In order to accomplish these goals, he refuses to negotiate.

Democracy in Crisis

HIRANO: What do you think about democracy in Japan? You mentioned to me on other occasions that you have some hope for Japanese young people, but it seems to me that the current situation is far from being optimistic. I have to wonder how postwar democracy has been functioning in this country. Observing the situation Japanese society is facing right now, especially after the Fukushima disaster, I am not quite sure how deeply postwar democracy has been established in this society.

MURAKAMI: I believe that one of the basic principles of democracy is the existence of the individual, but in Japan I feel that once each individual citizen is put into a big group, the individual is weakened or almost disappears. That’s why democracy cannot take root in this country. A lot of people think that democracy means deciding things by majority vote. But I don’t think so at all. Some people even say that once a political party wins by majority vote, citizens should not object to what the party decides. They believe that is what should be done in a democratic society. I believe that democracy means to listen to and respect each individual opinion, including opinions from the minority. The basic principle is individualism, and democracy does not exist as long as individual dignity is denied. I think the time has come again for us to be reminded how important it is to respect each individual’s dignity.

HIRANO: What do you think citizens in Japan should do when democracy as a political system is on the verge of crisis? When the Abe administration has been pushing to restart some of the nuclear reactors and public opinion seems to be going along with it, what do you think citizens can do? For example, would it be of any help to hold workshops or study groups to re-examine and discuss the Constitution? Or is direct action necessary?

MURAKAMI: I think the most important thing now is to have people who are aware of these problems begin to go over the Constitution again and re-examine its underlying spirit by questioning its origin and background. As I said earlier, unless we achieve profound understanding of Japanese history and the history of pre-war Japan and examine how the Constitution was created, we will not fully comprehend and appreciate what is written in it. Now that Japan is facing a crisis of democracy, I believe the active understanding of the Constitution may be able to save the situation. There are citizen movements, and we could say that people in the movements are new types of individuals, but I am worried that this could move in a dangerous direction, potentially leading to fascism. For example, recent growing anti-China and anti-Korea sentiments could lead in that direction. As the Nazis targeted the Jews, certain groups of people become a target. This is one of the characteristics of totalitarianism or fascism. I often hear the term, populism, but I find it alarming. People find a target inside the country, like the permanent ethnic Korean residents of Japan (Zainichi). Zaitokukai’s12 hate speech and internet right-wingers are a case in point. This is exactly the same thing that the Nazis did to Jews. When I visited Europe recently, I learned that the Swedish Parliament has far-right, far-left and Center parties, and in Europe this is called democracy.

HIRANO: Democracy ensures and respects diversity, disagreement, and spirit of civil dialogue. But populism propels anti-intellectualism and a culture of hatred.

MURAKAMI: In the recent political climate, there is a tendency to denounce the left or anyone who disagrees with one’s own point of view. By using the word leftist blindly, people are encouraging hate speech.

HIRANO: I agree. They are normalizing racism and discrimination. They categorize everything and everyone that is inconvenient or stands in their way as “leftist” or “traitor.” They even come up with a conspiracy theory, namely that leftists and traitors are working with China and South and North Korea to debase and weaken Japan. As you know, fascism functions well by targeting both internal and external enemies.

MURAKAMI: Exactly.

HIRANO: From what I’ve gathered, you are saying that the problem Japanese society has been facing since 3.11 results from the fact that it has not reflected on or deeply engaged with democratic values and thus has not established a firm basis for democratic practice. And the ongoing Fukushima crisis can be effectively dealt with only if people in Japan make a conscious choice of upholding the values of individual freedom and human dignity and decency as well as prioritizing the quality of life over economistic values and monetary gains.

MURAKAMI: Thank you for summing up so nicely.

HIRANO: Lastly, what do you think of the significance of Tōkaimura, the nation’s nuclear birthplace, becoming a leader of the anti-nuclear movement? Do you think there are certain messages that only Tōkaimura could disseminate to the world?

MURAKAMI: Tōkaimura has been made to play the role of a vanguard and a show window to promote nuclear power in Japan. It has also been carrying characteristics of living under nuclear colonialism. Tōkaimura’s history has aligned with the history of the promotion of nuclear development in Japan. Over the years, the Japan Atomic Energy Research Institute has played a hugely important role, but economically and financially, the Japan Nuclear Cycle Development Institute and Japan Atomic Power Company played a greater role.

It is true that Tōkaimura has been proud of being Japan’s nuclear power hub and being named the “Nuclear Center” or “Mecca of Nuclear Power.” As a result, it is possible to do everything in Tōkaimura from nuclear fuel fabrication, power generation and fuel processing. In the process, everything, including nuclear waste management, of course, was imposed on Tōkaimura.

On the other hand, it is also true that Tōkaimura used to be an impoverished village without even a brewery of sake, miso or soy sauce until the nuclear power plants and related facilities moved in. Therefore, the consciousness that all of the development and prosperity that the town has enjoyed since the 1960s is due to the nuclear power industry still exists strongly among residents.

Farmers were given employment at a nuclear facility, and merchants got contracts with the industry and no longer had to work hard to prosper. Also, cash flowed into the village from the sale of land to accommodate employees from Hitachi-related companies.

In this way, Tōkaimura gradually established an ethos and system within the administration and city council that would accept anything from government and industry without hesitation. The village has become an impregnable fortress and an incredibly cozy place for the promotion of nuclear energy. However, the JCO criticality accident came as a sort of rude awakening. This is a country that lacks the ability to keep nuclear power plants; therefore we should immediately follow Germany’s path of total abolition of nuclear power.

The Japanese government under Abe has been pushing to restore the previous energy policy that prevailed before the Fukushima nuclear accident. They say that the government will take full responsibility, but our government has no ability to do so. That’s the reality of this country. We must wake up and realize how senseless it is to rely on nuclear power that would result in loss of control and lead to a major disaster if something goes wrong even once.

Recommended citation: Katsuya Hirano, “Fukushima and the Crisis of Democracy: Interview with Murakami Tatsuya”, The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 13, Issue 21, No. 2, May 25, 2015.

Katsuya Hirano is Associate Professor of History, UCLA. He is the author of The Politics of Dialogic Imagination: Power and Popular Culture in Early Modern Japan (U of Chicago Press). He has published numerous articles and book chapters on the colonization of Hokkaidō, settler colonialism, cultural studies, and critical theory, including “The Politics of Colonial Translation: On the Narrative of the Ainu as a ‘Vanishing Ethnicity’”.

Akiko Anson is a freelance translator who lives in Iowa City, Iowa. Anson obtained a BA degree in English literature from Gakushūin University in Tokyo, Japan and an MA degree in Asian Studies from the University of Iowa.

Related articles

• David McNeill and Paul Jobin, Japan’s 3.11 Triple Disaster: Introduction to a Special Issue

• Oguma Eiji, Nobody Dies in a Ghost Town: Path Dependence in Japan’s 3.11 Disaster and Reconstruction

• Andrew DeWit, Fukushima, Fuel Rods, and the Crisis of Divided and Distracted Governance

• Anders Pape Møller, Timothy A. Mousseau, Uncomfortable Questions in the Wake of Nuclear Accidents at Fukushima and Chernobyl

• Asia-Pacific Journal Feature, Eco-Model City Kitakyushu and Japan’s Disposal of Radioactive Tsunami Debris

Notes

1 Nakasone Yasuhiro served as Prime Minister of Japan from November 27, 1982 to November 6, 1987.

2 Shōriki Matsutarō was a Japanese journalist and media mogul. Shōriki owned the Yomiuri Shimbun, Japan’s largest daily newspapers, and founded Japan’s first commercial television station, Nippon Television Network Corporation.

3 J-PARC is a high intensity proton accelerator facility. It is a joint project between KEK and JAEA and is located at the Tōkai campus of JAEA. J-PARC aims for the frontier in materials and life sciences, and nuclear and particle physics.

4 Koide Hiroaki is former assistant professor at Kyoto University Research Reactor Institute (KURRI). He has been advocating abandoning all nuclear power for last 40 years and is now a leading voice of the anti-nuclear movement in Japan.

5 This refers to the economic policies advocated by Abe Shinzō A since the December 2012 general election.

6 Futaba is located on the Pacific Ocean coastline of central Fukushima. The Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, owned by the Tokyo Electric Power Company, is located on the southern border of Futaba in the neighboring town of Ōkuma. The Fukushima nuclear disaster transformed Futaba into a ghost town.

7 Minamata is a city located in Kumamoto Prefecture, Japan. It is best known for neurological disorder caused by mercury poisoning. The disease was discovered in 1956. The Chisso Corporation’s chemical plant was responsible for causing the disease by emitting untreated wastewater into Minamata Bay.

8 Municipal mergers and dissolutions carried out in Japan from 1995-2006. Most of Japan’s rural municipalities depend heavily on subsidies from the central government. They are often criticized for spending money for wasteful public enterprises to keep jobs. The central government, which is itself running budget deficits, has a policy of encouraging mergers to make the municipal system more efficient.

9 The guidelines made in 1940 for the construction of the Greater East Asia Co-prosperity Sphere.

10 In 1941, the Japanese government made the guidelines for a total war against Britain, Holland, and the US.

11 Article 13. “All of the people shall be respected as individuals. Their right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness shall, to the extent that it does not interfere with the public welfare, be the supreme consideration in legislation and in other governmental affairs.”

12 The Association of Citizens against the Special Privileges of the Zainichi is a Japanese political organization that seeks to eliminate perceived privileges extended to foreigners who have been granted Special Foreign Resident status. Its primary target is permanent Korean residents.