Memories of a Zainichi Korean Childhood

By Kang Sangjung

Translated by Robin Fletcher

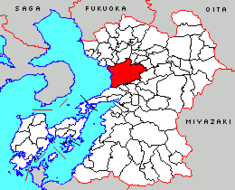

This extract from Kang Sangjung’s autobiography Zainichi (Kodansha, 2004) describes the experiences of first-generation zainichi Koreans in the city of

Pigs, moonshine and warm-hearted people

I am supposed to have been born on 12th August 1950, the 25th year of the Showa Era. But in fact, it seems that this is not my real birthday, since my parents apparently registered my birth according to the old lunar calendar. The sense of time indelibly imprinted on my parents’ minds was that of the lunar calendar. Even today, the customs of the past still live on in my mother’s notion of time. By remembering people’s birth, growth and death according to the old time of the lunar calendar, my parents perhaps found a way to affirm their connections to their homeland and their ancestors. In any case, I was born right in the middle of the Korean War, in a Korean settlement [1] close to the main station of

Local histories of

Kumamoto in red

The place where I was born—the neighbourhood of Haruhi-machi, near Kumamoto Station—was an area which seemed notably left behind by the reconstruction process. To the west side of the railway line lies Hanoka Hill, famous as the place where 19th century westernisers established the ‘Kumamoto Band’.[4] The Korean settlement was crowded together on the gentle incline of the neighbouring Banka Hill. In those days, over one hundred Korean families lived shoulder to shoulder there, all living in shabby makeshift tenements.

The Korean people of the settlement supported themselves by keeping pigs and making ‘moonshine’, illicit liquor [doboroku]. Scenes reminiscent of

Communal life there was coloured by roars of laughter and anger, by lawlessness and misery. Everyone was in a state of despair. Yet still they clung to faint wisps of dreams, and struggled desperately to find some means of subsisting in the harshness of daily work. The only means of survival left to them were brewing moonshine and keeping pigs.

Occasionally, when I was four or five years old, I would witness raids by excise officers on the illegal brewing operations. For some reason, I vividly remember one scene of a line of trucks coming up the hill towards the rickety huts which served as stills where the moonshine was brewed. The whole settlement was thrown into turmoil, like a hive of angry bees. I can still hear the cries of “aigo” [alas!] echoing across the hillside. I shall never forget the sounds of anger and grief in the voices of those people whose meagre means of livelihood were about to be destroyed. In my childish mind, I formed the sense that we were somehow living in an outlaw world.

On that unforgettable day, my mother hurled a stone at one of the excise trucks. Its windscreen shattered, and the vehicle was forced to come to a halt.

My mother, who was by nature the most nervous and sensitive of people, seemed for once to have been seized by a fierce anger. Seeing her rage at the officials who were destroying people’s lives took my breath away, and for a moment I couldn’t utter a sound. Having hurled the stone, my mother’s knees gave way and she fell to the ground, beating her chest with her fists and breaking into sobs. “Why are we forced to endure such sorrow?” That, I think, was the scream that lay beneath my mother’s weeping.

That day, my mother was taken away to the police station. I stayed close to my father, and, sensing from his anxiety that something terrible was befalling us, could not stop myself from crying. I cannot now remember exactly why—perhaps it was because the truck driver had fortunately not been injured—but mother was soon allowed to return home. The incident shows the courageous side of my mother. In these lower depths, life was driven by constant desperation, but for some reason the grown-ups always treated me with kindness and I received much affection. At least as far as I am concerned, that place conjures up only fond memories.

It may have resembled the impoverished marginal communities depicted in Kumai Kei’s film Apart from life, but I had the good fortune to experience the love and kindness of the adults, and so the impression I formed of the archetypal zainichi landscape was of a kind and warm community made up of unfortunate people.

How my parents became ‘first-generation zainichi’

Not far from the settlement, there was a small construction company called Takadagumi. My father worked there as a watchman. Takadagumi had operated since the prewar period, using hired construction workers. Our home was a tiny free-standing house in the midst of the settlement, towards the bottom of the hill. There I was born, and there our family of four lived – my mother and father, a brother four years my senior, and myself. My father had come to

According to the prominent US historian of modern Korea, Bruce Cumings, during the 1930s with the impact of the economic depression and the forced industrialisation of the Korean peninsula, the majority of Korea’s farm population left agriculture and moved to cities and industrial areas. As the boundaries of the Japanese empire grew dramatically following its war with

My father was just one young man from a poor farming family who was caught up in the sufferings of this vast and chaotic movement of people. The heavy burden of the times lay on his shoulders, condemning him to a harsh future. My father’s youth in

Father looked like the peasant farmer he was, stockily built, unsophisticated, and, perhaps weighed down by the burden of unremitting hard work, relatively short. By contrast, his younger brother (my uncle) was a tall and imposing young man with a handsome face. Remarkably for a person from the colonies, he studied law at university and eventually became a member of the Japanese military police [kempeitai], serving in

In the year the Pacific War broke out, my mother came over from her

My mother had been deprived of chances for education as a child and she was illiterate, unable to read or write Japanese or even her mother tongue. This devoted new bride, dressed in traditional chima-jeogori[5] and barely able to utter a few words of broken Japanese, seems to have been a figure of curiosity to those around her. Apparently she was often surrounded by groups of neighbourhood housewives making scathing comments about her clothing, and all she could do was stand there burning with embarrassment. The joy and sorrow of zainichi existence settled like a sediment in my mother’s heart, from time to time bursting forth in the form of mournful songs or of rushes of passionate emotion.

As the war situation grew worse and air-raids on

Taking their son’s ashes with them, my parents moved from

For the colonies,

The settlement was looked on as a kind of ghetto, an alien space in the midst of

Life amidst people of the ‘lower depths’

When I was six, our family left the settlement where I had been born, and moved to the foot of

Unlike my mother, my father was not entirely illiterate. He could read and write some Japanese. All the same, it was really difficult for him to get a driver’s licence. I still recall the resolute expression on my father’s face as he sat in bed first thing in the morning struggling with the questions for the test. Every adult is supposed to be able to apply for a driver’s licence, but for first-generation immigrants burdened with the handicap of dealing with a foreign language, acquiring a licence was undoubtedly a painfully difficult hurdle to clear. On his second try, my father, remarkably enough, was successful and soon after our family acquired a little three-wheeled vehicle called a ‘Midget’. After that, every day my father would leave home at the crack of dawn and not return until late at night. Day after day, he silently laboured away at his tough job.

For me, life in this unfamiliar place was a big change. I was cut off from the communal life of the zainichi settlement and plunged into the midst of a wholly Japanese environment. I felt alone, as though I had somehow become trapped on a remote island. For some reason, I missed the odours of pig-swill and dung, and the smell of brewer’s yeast. The environment and the people had changed, but all the same a remarkable assortment of people made their way in and out of our family’s garbage collecting business. Looking back, it truly seems like a human tragicomedy. I think I became almost painfully aware of the sighs of people who were relegated to the very bottom of society and were desperately trying to keep body and soul together. This, moreover, was a ‘lower depths’ different from that of the settlement where we had lived before. The difference was that the main characters who appeared in our lives were now ‘Japanese’.

My mother, who could not read, had to take on a whole range of tasks, from calculating the items and numbers and value of the scrap that was collected to single-handedly conducting business negotiations. For this purpose, she worked out a system of symbols which only she understood, and which she memorised in place of Japanese characters. I think her excellent powers of memory were probably the result of desperate efforts to make up for the handicap of illiteracy.

So, little by little, our family’s scrap business got underway. This precisely coincided with the start of

One thing that remains firmly fixed in my memory is the mass of military swords, helmets and other discarded weaponry which was heaped up in front of our house. It seemed uncanny to see so many swords rusted reddish-brown together with bloodstains. They bore the unmistakable smell of war. My mother, perhaps following Korean purification rites, would sprinkle salt around them, murmuring prayers as she did so. Memories of war, reeking with blood, lingered on even in a place like this. It was the business of garbage collectors to clear away the brutal carnage left by history. I am sure my mother instinctively understood this.

My parents’ struggling family business was also sustained by another first generation zainichi who came to live in our house as part of the family. This man, whom I knew from my early childhood as ‘Uncle’, had sworn an oath of brotherhood with my father, and thus become part of our family. ‘Uncle’ became as much as or even more than a second father to me. Later, after ‘Uncle’ had died, I learned for the first time that he had left a family of his own behind in Korea and come to Japan by himself, his lot thereafter that of a man with no home of his own. He had knocked about in the world of outlaws, and had at one stage apparently been quite an influential figure. Subsequently he had fallen on hard times, though just how he had ended up living with our family I do not know. However, as I shall explain later, ‘Uncle’ played an enormous part in my education.

‘Uncle’ was just one of the wide variety of people whom I encountered in the world around me at that time. They all had their share of hardship, and it seemed to me that they all lived with desperate intensity. Even today, I cannot forget them.

Across the street from our house was a man who could have stepped straight out of the textbook ballad of “The Village Blacksmith”. In his roaring furnace he heated iron and shaped it to his will, producing reaping hooks and hoes and other farm implements before your very eyes. He was immensely skilful, and his wares were of the highest quality. He was a big, uncouth-looking man, but a very gentle person. Every now and then, from over the other side of the road we would hear an astonishingly loud sneeze, which told us that the blacksmith was busy at work again today. It was somehow a reassuring feeling.

For one reason or another, the blacksmith and ‘Uncle’ got on well together. They didn’t have much to say to one another, but they seemed to understand each other nonetheless. “Tetsuo, that uncle of yours is a good’un. True enough, he calls you ‘Teshio, Teshio’. But he’s still a good’un.” ‘Teshio’ was as near as ‘Uncle’ could come to pronouncing my name, and I think maybe the blacksmith, who really understood ‘Uncle’s’ true nature, was trying to comfort me. Not long after, however, the kind-hearted blacksmith was suddenly struck down by a heart attack and died. The sound of hammer on metal and the mighty sneezes fell silent.

It was Mr Iijima who gave me a glimpse of the horrors of the adult world.

In those days, wild dogs roamed around everywhere, and were a major nuisance. We used to call the person who was employed by the dog pound to round them up ‘the dog killer’. The phrase contained feelings of both fear and contempt. Mr Iijima, with his little moustache, seemed amiable enough, but when he came to our house our pet dog seemed to be overcome by terror. It would make low whining noises and crouch ready to hide under the floor. “That there dog knows a thing or two! It’s years since I was the ‘dog killer’, but I reckon the smell still hangs about.” The events of a certain night made me wonder whether the smell of human blood, as well as that of dogs, clung to Mr Iijima. He was very drunk, and began recounting how during the war in

When I came to understand the memory of war as a political problem, I found myself often thinking of Mr Iijima. It seems to me that the war memories of ordinary soldiers were carnal sensations of slaughter remembered with great force throughout their bodies, and that when the war came to an end, such things were not to be spoken of openly—at the most, they could be vented as a sort of confession in the midst of the droning nonsense which drunkenness allows. There was no sense of guilt, but also no powerful sense of self-affirmation, just a sentimental attachment to a sad and shabby experience, one which was only loosed by alcohol, history recalled as a transient memory.

I don’t know what happened to Mr Iijima after that.

Writing of unforgettable people reminds of ‘Kaneko-san’, a good friend of ‘Uncle’s’. Perhaps because ‘Kaneko-san’ was from the same zainichi background, he was in and out of our house all the time.

To the north of our house, on the way to Yamanaga, was Keifuen, the famous leprosarium. The Precautionary Measures against Leprosy [Raiyoboho] have now been repealed but in those days the policy of isolation was in force and it seems that Keifuen even had rooms constructed for solitary confinement as a disciplinary measure. Surprisingly enough, however, despite the rigorous isolation policy of the times there were occasions when the inmates went outside. One of my playmate’s parents ran an amazake[6] and steamed bean-cake shop, and there were patients from the leprosarium among their customers. My friend’s parents were good, kind people, so a particular incident made an immense impression on me. My friend’s mother used chopsticks to take a hundred yen note that a customer with Hansen’s Disease held out between two fingers, and then put it in the steamer. I think she also handed over the bean-cake in some sort of little bamboo basket. This was forty years ago, but I remember the scene as if it were yesterday. I was absolutely stunned that a usually admirable adult could behave so cruelly to those who in those days were literally treated as ‘untouchables’.

I seem to remember, though, that when ‘Kaneko-san’ came to our house, I would always scurry off and take refuge in the back room. I didn’t know why, but some ill-defined fear just seemed to chase me away.

It was completely different with ‘Uncle’ and my parents, though. My father and ‘Uncle’ were quite comfortable about collecting garbage from the leprosarium, never showing the slightest fear or hesitation. On occasion, they even shared the inmates’ meals, helping themselves from the same dish. They often invited them into our home, too. It seems to me that they felt sympathy or something like kinship, perhaps because they shared the unfortunate consciousness of living as ‘outsiders’ in

Both my father and ‘Uncle’ have passed away, and my mother, now eighty, spends much of her time in bed. I hear that ‘Kaneko-san’, though, despite the Hansen’s Disease which used to be feared as an incurable, is still hale and hearty and seems set to live to a ripe old age. The Precautionary Measures against Leprosy were repealed and the nation apologised, but prejudice and preconceptions linger stubbornly in people’s minds, and it does not look as if they will be overcome in ‘Kaneko-san’s’ lifetime. If I could meet ‘Kaneko-san’ again, I would like to apologise sincerely for my own past—and I have come to wish that the two of us could together retrace our memories of my father and ‘Uncle’.

A way of living as ‘zainichi’

It was from the woman from

The woman from

The woman from

The neighbourhood gossip was that there was something odd about young Tetsuo’s family—all those gongs and drums. Perhaps his mother had a screw loose … All I could do was will those few days and their ceremonies to be over as quickly as possible.

In my twenties, I discovered my name and that of my elder brother engraved on the small shrine at nearby Suigenchi. This epitomised my mother’s concern for the security and good fortune of her two children, and brought home to me once again how deeply she loved us. Years later, the woman from

One can view this world of my mother, the woman from

The rituals did not end there. That is to say, regularly as clockwork, when the correct season came, the woman from

The people engraved on my memory, bound up in these complex feelings … When I look back now, I see how they gave shape to my memories. It may be that my ‘homeland’ is to be found in memories like these.

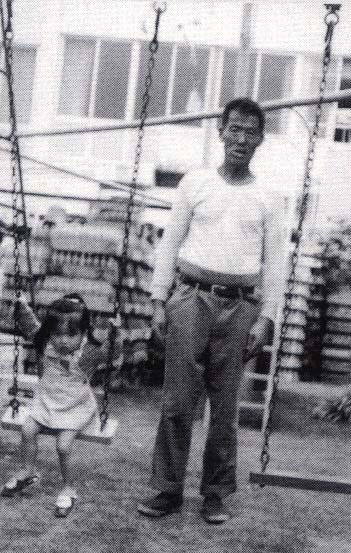

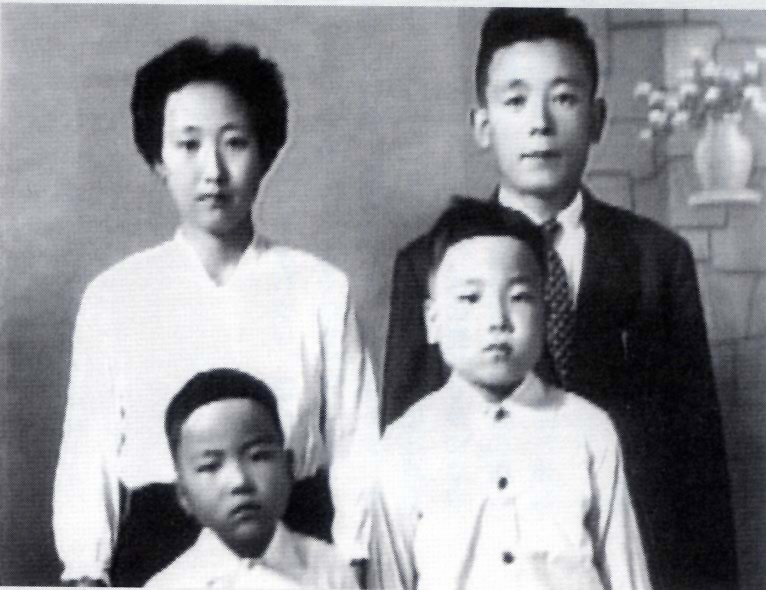

Kang Sangjung (front left) and his family

A member of the zainichi ‘elite’, who became a military policeman

In writing of my life so far, I cannot possibly neglect to mention my two uncles.

As I wrote briefly earlier, one of them was my father’s only younger brother, and so my uncle by blood; the other was not a blood relative, but the ‘Uncle’ who was virtually a second father to me. Both were first-generation zainichi, but their life circumstances could scarcely have been more different.

My blood uncle, extraordinarily for a Korean during the war, received a Japanese university education. The year before the war came to an end, he joined the military police and was stationed in

For a colonised people, the day of

Not long afterwards, my uncle returned to his homeland to ascertain how things were in his mother-country. He went alone. The old country which my uncle encountered had been thrown into the tragic chaos of ‘contemporary history’ [gendaishi], disorder which lasted from the day of liberation until the bitter civil war and the birth of the divided nation now known as the Republic of Korea and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea. Caught up in this, my uncle again donned army uniform, becoming a judicial staff officer and taking up military duties. Amidst the chaos and ruin, he gave up hope of ever seeing his family again. After the Armistice, he became a lawyer, establishing a practice in

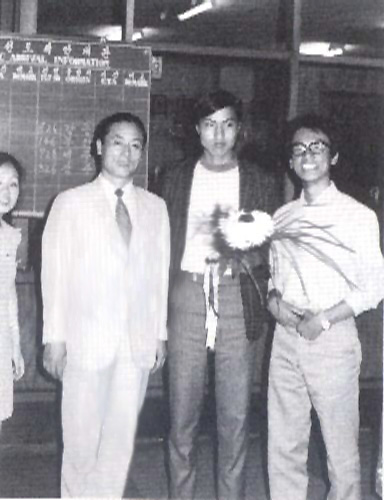

When the Osaka Expo took place in 1970, my uncle returned to

My uncle had wiped out all memories from before the war, of having been a member of the ‘pro-Japanese faction’ military police, of the wife and child he had left behind in

After my father’s death, my uncle seemed eager to follow him. His family scattered, and his spent his last years lonely and alone. How, I wonder, did those expunged memories of his time in

I cannot find it in my heart to condemn my uncle’s ‘anti-ethnic’, ‘pro-Japanese’ past. Even without such condemnation, the past has certainly exacted appropriate revenge through the burden of sad memories he bore throughout his life. While accepting this, I have thought that even so I would like to bring to light once again the memories and history that my uncle blotted out, and throw into relief the nuances of the intricate cross-grained relationships between the ‘defeat’ and ‘liberation’, and Japan and the Korean peninsula. I regard this is the weighty task that has been left behind for me.

Kang Sangjung (centre) with his uncle (left) in Seoul, 1972

‘Uncle’ who lived as an exile in the shadows

In striking contrast was the life of my other ‘Uncle’. Unlike my father’s younger brother, ‘Uncle’ had no education to speak of, and remained illiterate all his life. He had been a yakuza and active in the outlaw world in his youth, but eventually his life fell apart and he finished up in my house despite being no relation. Always having time for me, he stood in for my busy father.

‘Uncle’s’ name was Yi Sangsu. His Japanese name was Iwamoto Masao. For almost thirty years I was completely unaware of ‘Uncle’s’ original name. He was always there, occupying such an incalculable place in my memories that it just never occurred to me to inquire about him. Sadly, it was only when ‘Uncle’ died that I learned of Yi Sangsu for the first time. I am sure my father felt with painful intensity that he wanted ‘Uncle’, who had no relations of his own, at least to be buried under his ‘real name’. This encapsulates the heartbreak of first generation zainichi like my father and ‘Uncle’, who did not speak openly about ethnicity. When I learned that ‘Uncle’ was Yi Sangsu, I felt a deep sense of shame at my own lack of awareness, and wept as I understood the depth of their sorrow.

It may well be that ‘Uncle’ was so good to me because he saw in me a trace of the child he had left behind in the homeland.

‘Uncle’ was vigorous and tough, a man of few wants. Even so, at times his face would be melancholy, shadowed by loneliness. When I think about it now, I am sure that at such times he was looking back with regret at the man who had abandoned wife and child and lost his home. ‘Uncle’ did not grumble about his hard lot, however; his dauntless personality probably did not permit it. I think he probably accepted it as something he would have to go on enduring stoically, and determined somehow or other to work his way through. Even so, his pent-up feelings would sometimes burst out with passionate emotion—“My country has come to this … my life has come to this … and yet I still feel …”. As his words came to a halt and he fell into silence, I think ‘Uncle’ was mourning bitterly.

More than anything, ‘Uncle’ loved politics. When he talked about politics, ‘Uncle’, face flushed, was in his glory. He would often be found lecturing ‘Kaneko-san’, whom I mentioned earlier. ‘Kaneko-san’, with his good will for the ‘North’, and ‘Uncle’, who believed in the possibility of change in the ‘South’, were both concerned about the well-being of their families as they intently discussed the future of the mother-country. As I watched them from a distance, I felt there was something remote about the two absorbed figures. This ‘adult’ face was quite alien to the ‘Uncle’ of every day.

‘Uncle’ sometimes told us about social conditions or international relations, based on the store of information he had picked up from here and there. Such-and-such a politician was in a class of his own… this politician was really somebody … there was no politician nowadays who could pull off a thing like that … and so on, and so on. In general, ‘Uncle’s’ interest was in the person, and based on that he added to his store of knowledge of events and circumstances. It seems to me his critiques were often sufficiently accurate to take even a political analyst aback. He certainly had a real political intuition.

It wasn’t only political lectures—‘Uncle’ was also my guide to an unfamiliar world. At a time when entertainment was scarce, when television was a luxury only to be dreamed of, movies were the window onto the world of pleasure. ‘Uncle’ was a huge fan, and many a time he took me along. Whenever I perched on the front of ‘Uncle’s’ bicycle as we headed for the cinema, my heart would beat with such excitement I could hardly breathe. And as we made our way along the dark road home, ‘Uncle’ and I would grow quite heated as we discussed whatever film we’d just seen. As ‘Uncle’ pedalled cheerfully along under the bright moon, myself in front, there was a kind of warmth deep in my heart.

‘Uncle’ worked alongside my family, collecting garbage and feeding the pigs. I stuck to ‘Uncle’ like glue, and loved helping him look after the pigs. The daily routine of preparing the food and cleaning was hard physical work, but ‘Uncle’ toiled on, silent and intent. His compassion for living things was very evident when the sows were farrowing. His careful ministrations as they groaned in their labour pangs made a lasting impression on me.

‘Uncle’s’ compassionate kindness was also directed to animals that met untimely deaths. Our house faced a national highway, and was often littered with the pathetic carcasses of dogs and cats that had been hit by cars, victims of the rapidly rising volume of traffic. Everyone else would avert their gaze, but it was always ‘Uncle’ who would unobtrusively go and pick up the bodies and carry them in a straw mat to the bank of the nearby river, where he would give them a dignified burial. Did ‘Uncle’ perhaps identify with the lifeless bodies of those ‘dumb creatures’ which had met with a sudden, meaningless death? It made my heart ache to watch him the time he returned from the riverbank after burying a dog he’d particularly loved, smoking in stony silence.

‘Uncle’ got drunk on so little that his one indulgence was cigarettes. There was always a packet of ‘Peace’ jammed into his back pocket. I loved ‘Uncle’ when he was smoking, most of all as he sat tranquilly in a corner of the extensive stadium at the University, puffing away as his gaze wandered idly over Mount Tatsuta before him.

‘Uncle’ and I would go each day to pick up leftovers from the kitchens of the student dormitories at

When I think about it now, though, I am sure that ‘Uncle’s’ heart was full of homesickness as he gazed silently into the deep recesses of the mountain.

‘Uncle’ died in hospital with a deep sigh, as if to breathe out all the hardships of this world. I broke down and wept.

I want to meet ‘Uncle’ once again. I was not able to ward off his sadness—even if I knew Iwamoto Masao, I did not know Yi Sangsu. There are times when I am haunted by the thought that it could be said that I never met the real ‘Uncle’. I want to meet Yi Sangsu, once again. Surely the only way to do so is to ‘go forward’ by facing the past. It seems to me that this feeling will grow stronger with the years. It may even be that the motivation for my actions in speaking on social issues is the strength of this feeling.

When ‘Uncle’ died, he had virtually no possessions. He left behind a pair of gumboots encrusted with food scraps and pig dung, and a jar containing a few cigarettes. As I gazed at them, I asked myself over and over again what ‘Uncle’s’ life had been, indeed, why on earth he had even been born. An exile from his homeland, ‘Uncle’ had lived out his life quietly in the shadows. When he was suddenly felled by a stroke, he tried to brush away the helping hands, surely signalling that he had had enough of living.

The two uncles who influenced me so deeply… When I compare their widely-different lives, I finish up reflecting on what it meant to live as a first-generation zainichi. It is fine, as far as it goes, to say that it was a cruel life imposed on them by historical forces. But it seems to me that although battered by life, they both survived, doing the best they could with the means at hand. My ongoing wish is to ensure that the memory of those ‘mutants’ who survived the rigours of their lives does not disappear from the places where they lived.

Torn into pieces time and again

As one follows the traces of my two uncles, the misery of their lives, torn to pieces again and again, surfaces. Their misery is intertwined with feelings of powerlessness and loss. But although they were stricken with grief, they got on with their lives.

One thing they were denied was seeing their country united. What of second generation zainichi like myself, who live on with memories of them? I have still not had the opportunity of seeing my ‘homeland’ united. When I say ‘homeland’, it does not of course have the same sense of ‘native place’ [patrie] as it did for my uncles. My ‘native place’ is

And yet, I want to take the plunge and write of the Korean peninsula as my ‘homeland’. By doing so, I wonder whether I may be able to re-discover bonds with my uncles. I wonder whether perhaps I will be able to discover my ‘homeland’ in their memories. Of course, they are no longer alive. Even so, the actuality of the division which was responsible for their misery still continues. Might it not be that when that stark reality is confronted and ended, I will be able to meet my uncles again and begin to say “at last the time has come when your heartache (han) [9] can fade away.”

Today I am a university professor and have achieved a certain degree of public esteem. The contrast with my uncles is obvious. I cannot rid myself of a feeling of shame that I perhaps never really met them, and even now I have not had the joy of seeing a unified

By the time I was in upper primary school, there was an intangible sense in society at large that there was something almost criminal in the very fact of being zainichi, and even worse was the hard fact of division. Why was my parents’ and my uncles’ mother-country being divided? Why was it fighting? Was the Korean race belligerent by nature? When I thought about it, I had to admit that many of the first generation wore their hearts on their sleeves; they were aggressive, abusive and quarrelsome—and so I supposed it might make sense that the country was divided and members of the same race were killing each other. What a ‘barbaric’ people! Images and concepts like these formed one after another, leaving me always heavy-hearted.

History and modern society lessons at school were truly wretched experiences for me. I was seized by a feeling of desolation, as if I had been left all alone in the classroom. Why was I a zainichi? Why were we ‘at the bottom of the heap’? Such misgivings troubled me deeply, but there was no friend or teacher in whom I could confide. I had no alternative but to bury my anxieties deep within myself, and as a result, it was as if a dark cloud of disquiet hung over me.

I was good at both schoolwork and sport, and probably seemed a cheerful, mischievous boy. But at times the cheerfulness would be erased by melancholy and disquiet. There was no real knowledge of or insight into the significance or the origins of division, but it definitely cast a dark shadow. Zainichi—rootless like tumbleweed, deprived of the protective carapace of ‘nation’, fighting among themselves even when in a foreign country, the country to which they should return split in two. In the popular mind, they were nothing short of ‘the dregs of history’. Even the well-meaning people around me were probably unable to imagine how dark a shadow this negative image cast over my young heart. And yet the division was not unrelated to Japanese history.

Later, when I was studying in the former

One could perhaps in a way regard the division of

When I retrace my childhood memories, I feel a melancholy deeper than simple nostalgia, a melancholy that has continued as I grow older. Why, I wonder? I cannot help but think that the answer lies in the circumstances of being zainichi, of which division is the symbol.

There is a complex emotion in zainichi. Some of the younger generation talk of there being two streams within themselves—the country they love most in the world is

I think my melancholy usually arises from this sense of division. Division must be healed through reconciliation, not force. It may be, indeed, that reintegration can never be fully achieved. Yet surely it is possible to dispel insecurity by allowing the ‘other’ to enter oneself and co-exist with that ‘difference’? It may be that in the final analysis, it is simply impossible to speak of fundamentally dispelling insecurity. But surely even if the insecurity cannot be dispelled, the heart may be lightened by confronting its source, accepting it, embracing it?

I somehow feel that when even some small reconciliation takes place between the divisions between ‘zainichi’ and ‘Japan’, ‘zainichi’ and ‘North/South’, ‘North/South’ and ‘Japan’, I will at last be able to meet my uncles.

The unification and co-existence of North and South is not simply a matter of bringing together a divided country. The process of reconciliation is itself of great importance. Reconciliation of North and South will necessarily also be bound up with simultaneous reconciliation with

Translator’s postscript

The aging of the first generation of zainichi Koreans who are the main subject of this essay brings sadness and the vanishing of individual histories, but also sometimes opportunities for remembering. On 3 April 2005, Kang Sangjung’s mother U Sunnam passed away peacefully in

Notes to the translation

[1]

[2] The General Headquarters of the Allied Powers (GHQ) declared that Koreans resident in Japan, whether of Northern and Southern origin, were neither citizens of the victorious countries nor of the defeated countries, but were described as ‘third country nationals’.

[3] When a bomb of unknown origin ripped the Japanese railway near

[4] In 1871, American teacher Leroy Lansing Janes established a school in

[5] Traditional dress for Korean women consists of a short upper-body garment, folded in front similar to a kimono (jeogori), and a pleated long full skirt, gathered above the waist (chima). (Translator’s note)

[6] A sweet drink made from fermented rice, sometimes flavoured with ginger. (Translator’s note)

[7] Itako, blind female shamans or spirit mediums, are renowned for their capacity to speak for the dead, through a ritual process known as kuchiyose.

[8] Park Chunghee (1917-1979) was president of

[9] Broadly definable as a sense of deep sorrow and a desire for restitution invoked by the sufferings and oppression of history, han is often seen as one of the defining elements of modern Korean culture. (Translator’s note)

This translation of the first part of Kang Sangjung’s autobiography Zainichi (Kodansha, 2004) was first published in Japanese Studies Volume 26 Number 2 December 2006, pp 267-281. Posted on

Note on the translator

Robin Fletcher received her PhD from the Australian National University in 2005, for a thesis entitled ‘Yaeko Batchelor, Ainu evangelist and poet’. In addition to researching Japanese history, she has translated a number of Japanese works, including the collected works of Yaeko Batchelor.