Edan Corkill

If the entire Japanese architectural fraternity was one big royal family, then Isozaki Arata would be a king approaching the end of a long and glorious reign.

The “pedigree” of this majestically silver-maned 76-year-old is, quite simply, faultless.

Architecturally speaking, Isozaki’s “father” was the great Tange Kenzo — best known for his 1950 Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park and the National Gymnasium in Yoyogi built for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. Isozaki was taught by Tange at the prestigious University of Tokyo in the early 1960s — along with those other architectural luminaries, Kurokawa Kisho and Maki Fumihiko.

But then, tracing Isozaki’s architectural roots back past Tange leads straight to Maekawa Kunio, with whom Tange worked just before World War II. In terms of modern Japanese architecture, it might well be said that Maekawa was the first, the original king before Isozaki. After working for Le Corbusier in Paris in the 1920s, Maekawa became one of the most important interpreters of Modernist architecture in Japan.

Like any great monarch, however, Isozaki’s conquests gradually spread further and further afield as they mirrored the growth of his stature. Beginning in 1964 with a humble public library in his native Oita Prefecture in Kyushu, his next large projects were dotted around Tokyo’s outskirts, including the Museum of Modern Art, Gunma (1974), the Tsukuba Center Building (1983) and Art Tower Mito (1990).

In these works he developed an original style built around simple concrete forms — giant rectangular prism-shaped galleries perched on stilts for the Gunma museum, for example, or spherical, pyramid-shaped and cubic masses arranged like children’s building blocks across a site at Tsukuba and Mito.

Then, by 1982, Isozaki was pioneering Japanese architecture overseas, making the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles (1986) and the Team Disney building in Florida (1991). In the United States, he also found that his playful use of shapes segued nicely with the dominant postmodernist penchant for a decorative flourish. For the Disney Building, he gave each of its component shapes a different color, and even incorporated a subtle Mickey Mouse reference in the form of an entrance hall shaped like the cartoon rodent’s ears.

Next month, Isozaki celebrates his 77th birthday — traditionally a highly significant age for Japanese people. Yet the architect, who now has his own “heirs” (former employees such as Shigeru Ban and Jun Aoki, who have now established their own reputations overseas), is showing no signs of slowing down. Indeed, amid his hyperhectic schedule, he even took time between business trips to talk to the Japan Times at his studio in Roppongi — not only about his latest works in China and the Middle East, but also about his own birthday plans as well.

The media often refer to the amazing construction booms happening now in China and the Middle East, but what it is like to be involved in all that as an architect?

It’s not like I deliberately chase the booms. Someone will call and invite me to participate in a competition somewhere, so I enter, and, if I’m lucky, I win. Then, all of a sudden I’m working in China, or the Middle East.

You have experienced many construction booms — Japan had one in the 1980s. What characterizes the current China boom?

In China, the problem was that in a very short period of time a huge number of buildings had to be made. That is partly because the population is so huge, and partly because once a development policy is passed it is implemented immediately. However, to nurture architects you need time — for their education, for them to gain experience. You just can’t do that in 10 years; it takes 20 or 30.

I believe the Chinese government realized they didn’t have the know-how to do the design and construction necessary, so they decided to allow a lot of foreign companies into the market. That happened around the end of the 1980s. It was something that Deng Xiaoping started.

What kind of work are you now doing in China?

In any city it is necessary for 95 to 99 percent of the buildings to be residential, commercial or business. Of course, with these buildings you have to maintain a certain standard of architecture. But it is also necessary to have a small percentage of buildings that are architectural standouts, and they should be the city’s cultural facilities. My policy has always been to focus on these cultural facilities — museums, libraries, universities, convention centers and so on. I like to partner developers who share this way of thinking. In China at the moment, I have a few projects under construction: the Shenzhen Cultural Center, in Shenzhen, for one. That is a concert hall. Then there’s the Central Academy of Fine Arts’ Museum of Contemporary Art in Beijing.

Has the Central Academy museum opened already?

It is opening in October. It’s pretty much completed now, with the school using part of the building already. The grand opening will be in October.

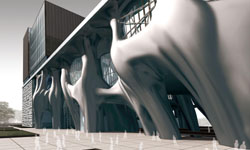

Your buildings used to be known for their use of cubes, pyramids and other simple shapes, but this is a very organic form with lots of curves. Where did that idea come from?

That way of thinking emerged during a certain period when I was doing a number of jobs. For example, the Domus: La Casa del Hombre in La Coruna in Spain, which was a museum focusing on the human body. It was completed in 1995. That was one of the first jobs that incorporated organic curves. At that time, works using curves started appearing more and more. The Central Academy job is a continuation of that, but at the same time, it further develops it. The entire structure there is complex and organic.

Isozaki’s curvy new design for the Museum of Contemporary Art at the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing, due for completion in October, seen inside and from the outside. Photo by Judy Zhou.

Recently, you’ve also done the Shanghai Zendai Himalayas Art Center. How is that?

That’s under construction. Half of it was designed using computers — the organic shapes at the bottom — and the top half is a more conventional series of square blocks. Part of the facade is also influenced by elements of Chinese characters. It’s a combined-use facility incorporating a museum and a hotel. The thing that I thought was like, you enter the hotel and you’re in a museum; you enter the museum, and there’s a hotel there. So you don’t make these two things separately, as has been the case in the past. Places like Roppongi Hills in Tokyo have several functions, too, but there are separate entrances for each of the components. So, if you were to think about something like that with a clean slate, then it should be possible to make a building where those two functions are really one.

The architect currently has several large projects in China, including the Shanghai Zendai Himalayas Art Center. Courtesy of Arata Isozaki & Associates.

You’re also working a lot in the Middle East. What is the boom there like?

At the moment I have two jobs under construction in Qatar: the Qatar National Library in Doha and a convention center. Qatar is essentially a monarchy. The lines between monarchy and democracy, and between what’s public and what’s private are not so clear. It is difficult to apply the same concepts as in the West; it is hard to know exactly how things work over there. By chance I got to know people close to the Emir, and I was then invited to build those projects. Construction progressed on the National Library for a while, but as a result of some political issues the work was put on hold. But I think when these problems have been resolved it will start moving again. Lots of strange things happen!

One of Isozaki’s current projects, the Qatar National Library, draws on a plan he had for a “city in the sky” in the 1960s. Courtesy Arata Isozaki & Associates.

The design is extraordinary, like the futuristic plans you made for west Shinjuku in the 1960s, where all the city would be raised on giant stilt-like columns.

Yes, that Shinjuku project was an idea to build a city, or at least a part of a city — the residential and office parts — up in the air. It was of course not realized at the time, but now those old ideas are coming back again.

After the Middle East, where do you think the next construction boom will be?

Now Russia is emerging too. If you look at the construction booms that I have experienced, they all started with my first job overseas, which was in Los Angeles — the Museum of Contemporary Art there. That was part of a very large-scale development. It was the same kind of project as the Mori Building’s Roppongi Hills in Tokyo, where they started with a large-scale development and then added in a hall or a museum to attract the people. MoCA was also the first museum focused on contemporary art in the world.

So, in America, in the 1970s and ’80s many large-scale developments were being made, and in Japan, too, at the end of the construction boom that continued through the 1980s, there were lots of ideas for similarly large-scale developments. Then the economic bubble in Japan burst, and all those ideas were scrapped. Now, I think the situation you see in Tokyo is that the ideas born in the bubble period are finally being realized. [Marunouchi and Roppongi Hills are examples.]

Either way, the construction boom that had come to Japan went away. Also, at the same time, the boom was happening in London, Berlin, Paris and other cities in Europe affected by World War II. Of course, postwar reconstruction was completed in the ’60s, but in the ’80s there was a time of renewing these areas. That’s where the Docklands development in London and the Postdamer Platz in Berlin and Mitterrand’s series of cultural developments in Paris (the so-called Grands Projets such as the glass pyramids at the Louvre and the Musee d’Orsay) came in. Then there was China and the Middle East — which looks like it might be the biggest of all — and now it is Russia and the former Soviet republics, Kazakhstan and places. At the beginning of next month I’m going to Ukraine.

The interesting thing is that the construction booms move around the world in waves. What happens is that a certain volume of development money just moves from one region to the next. Once they make something in certain areas the money goes back to the investors, and then they look for the next place to invest. After Russia, who knows where it will go! Maybe it will stop for a while.

Considering how busy you are, how do you manage to keep track of all this international work?

Well, I’m almost 77 — give me a break! About once a month I’m in America or Europe. Going to China is just like a domestic flight for me.

Do you have offices overseas?

I had some work for the 1992 Barcelona Olympics, and the person who worked with me there stayed behind and made an office. He’s Japanese and he’s like a representative for us over there. Same with China, except it is a Chinese architect who is our representative there. In Milan there is an Italian architect who used to work for me in Japan. In Poland, too, there is someone I work with, so if there is a job in that area then we will work together. But still, the difficult thing about being an architect is that, unless you actually go to these places, you can’t get them to trust you. But as for the more difficult places — the ones that require a lot of visits — well, I think I’ll slow down with them sooner or later. But it just doesn’t stop!

Your fame is such that you are often invited to judge large architecture competitions too, and juries you have been on have selected some of the most experimental architecture of the last few years — the weightless Sendai Mediatheque, made by Tokyo-based Ito Toyo in Japan and the gravity-defying China Central Television (CCTV) Building in Beijing, by Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas. What do you look for when you’re judging?

With competitions, one of the most important things is determining the real intention of the client — and understanding their capacity is also important. For example, with the Sendai Mediatheque [a cultural facility in Sendai, Miyagi Prefecture, famous for its “transparent” steel columns], it was a public project and their goal was to make something new. If you give architects a brief that is too normal, then you get something normal. I can’t take all the credit, but when I was consulted about the project, the first thing I said was, “Change the name.” The hoped-for function was for a library, a gallery and a community center. So I said, in France if a bibilioteque is a library, then why not call this Mediatheque?

Really? I always thought that was a good name.

Yes, and then when you put a new name on the brief — like Mediatheque — then the architects understand that you want them to put forward ideas that are unlike other buildings. The proposal we ended up selecting, by Ito, was certainly unlike other buildings.

The CCTV competition [a new headquarters for China Central Television in Beijing; the winning entry, by Koolhaas, is a gravity-defying “skewed arch” that is currently under construction] was a slightly different situation. There were between 10 and 20 judges, and each had only one vote. With CCTV there were a number of proposals — one from a Shanghai firm, of a high standard — then there was a very beautiful, Modernist plan by a consortium of Ito Toyo and a Chinese firm. The third proposal was by Koolhaas, and I decided it would be best. But, in order to get the jury to agree on Rem’s design I knew there were a lot of hurdles I would have to clear.

Of course there were objections from Beijing city officials, and from within CCTV, too. [The building, a giant arch, but with the horizontal cross-bar executing a 90-degree turn mid-air, looks like it could fall over at any moment.] When we were debating the proposals, I decided it was best to just not talk about function at all. I focused the discussion on the amazing appearance of the building, saying that it alone could best express the function of a TV station. They had the opportunity to create an example of what I called “iconic architecture.” That is what I said. The building itself will symbolize CCTV, like a giant corporate logo.

They ended up accepting it. After that I noticed that all over the world, the term “iconic architecture” became common parlance. All the developers are saying it these days — they want an “icon.” Now they don’t care what the function of a building is! You could call it archisculpture, perhaps — architecture as sculpture, or vice versa. With the Modernist focus on functionalism, this way of thinking was denied for a long time, so it’s not a bad thing that it’s coming back again.

You’ve made some buildings that have become icons yourself. What do you consider the highlights of your career?

The first work I did when I felt that I could make my own, original architecture based on my own concept was the Art Plaza in Oita Prefecture in 1964. I was very proud of that. And the first job that I really thought I could show to the world was the Museum of Modern Art, Gunma.

Interior and exterior of Art Plaza, formerly Oita Prefectural Library, which was completed in 1964 in Oita City in Kyushu, was the first building about which Isozaki says “I felt I could make my own original architecture.” Photos by Miyamoto Ryuji.

The Art Plaza is a rare example of where a local government has refitted a building for a new function. It was built originally as a library and in 1996 it was reborn as a gallery. Most governments in Japan seem to prefer the “scrap and build” approach, and just knock old buildings down.

Well, it’s usually quicker to scrap and build. In this case, too, when they decided to move the library elsewhere it would have been quicker to knock this building down and build a new one. But if they did that they would have ended up with a terrible building! Actually, the public voiced their support for keeping the original building, so it was turned into an art gallery.

Despite all this, your activities are not limited to architecture. In addition to writing, criticism and judging architecture competitions, you also get involved in large-scale public projects, such as Fukuoka’s bid to host the 2016 Olympics.

Yes, we lost to Tokyo, and now they are competing against other cities internationally. I had been thinking for a while about how it would be possible for Japan to host the Olympics somewhere other than in Tokyo. If you stage them in Tokyo, it’s the capital city, and the message of a “nation” becomes too strong. This always happens when a capital city hosts the Olympics. You know, technically speaking, the Olympics must not be held by a country; the host must be a city. But it’s got so big these days that the national governments support the host cities.

So I thought Japan should do something different. Fukuoka! It’s not a capital, not a country — it’s Kyushu. But my plan was much bigger than that. I wanted to involve Pusan in South Korea, Qingdao and Shanghai in China and if possible Taipei in Taiwan, too. I wanted to bring all these areas together — the countries, no, the cities that form a ring around the East China Sea, to become joint hosts of the Olympics.

I proposed that idea to Fukuoka and they officially made the presentation. I was told at the time that our plan was better than Tokyo’s. But, in Japan, these decisions are not made on merit alone; it’s money that talks. Tokyo had 10 times the population and 10 times the budget, so they gave it to Tokyo. It was a simple reason. It couldn’t be helped. But, this idea that I had, I think in the 21st century other areas will realize that it is the best choice.

That’s quite a revolutionary idea you had, and that reminds me: your first name, Arata, means “new.” Why did your parents call you that?

My father was a haiku poet, and he was part of what was known as the Shinko Haiku (New Haiku) movement. They wanted to transform the old style of haiku into a more contemporary style. So he was interested in new things, too.

Also, my mother’s father wrote kanshi, which is traditional Chinese poetry. I think my grandfather selected a few characters and my father chose this one.

This year you are celebrating your 77th birthday. What have you got planned?

I do architecture and urban planning. I’ve also done lots of work with artists. I write, half as a critic, half as a historian. The only way to present all of this work is through exhibitions. When I turned 60, about 20 years ago, they gave me an exhibition at Los Angeles MOCA to celebrate, and it toured the world for about three years. When I turned 70, the Deutsches Architekturmuseum in Frankfut, put on an exhibition for me, too.

But in Japan it is actually 77 that is the most important milestone. When you write the characters for 10 and 7 you end up with the character for yorokobu, which means “to celebrate.” This is the year of celebration, as far as I’m concerned. There are seven different exhibitions that I will be holding at different times during the year. You should come and see them!

Information about Isozaki’s seven exhibitions being held throughout this year can be found here. Highlights include an exhibition of his museum designs at the Museum of Modern Art, Gunma (until June 22), an exhibition of his residence designs at Art Plaza in Oita City, Kyushu (until January) and an exhibition about the exhibitions he has curated at Hara Museum Arc, Gunma (July 27 through Sept. 23). The exhibition at Hara, which was itself designed by Isozaki, coincides with the opening of a new pavilion that he has made for the institution.

This article originally ran in the Japan Times on June 1, 2008. Posted at Japan Focus on June 8, 2008.