Abstract

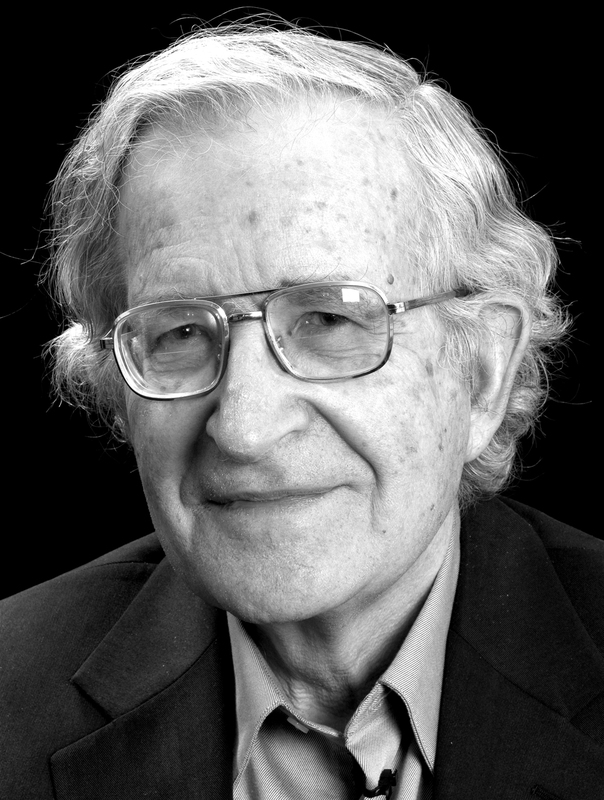

US censorship of public discussion of the bombings during the Allied Occupation of Japan ensured that the Japanese public knew little about the human consequences of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. When hibakusha poets seek a public audience for their poetry, their experiences make them potentially powerful public intellectuals. As Noam Chomsky has observed, the most effective public intellectuals are dissidents who act from the margins. Tōge Sankichi and Kurihara Sadako became activists and their poetry offers a powerful and rousing response to the atomic bombing and lobbies for nuclear disarmament. The simplicity and accessibility of these poems is essential to the public dissemination of their message and Kurihara’s and Tōge’s identification as public intellectuals. This article examines the ways in which hibakusha poets can be recognised as public intellectuals when they seek public audiences for their work. Discussion hinges on a number of considerations centred on public intellectualism, trauma and the uses of language.

|

Introduction

I visited Hiroshima for the first time in 2009. There is something about the A-bomb Dome and the way it is lit at night that makes for a stark and moving experience. The green lights have been referred to as ‘eerie’ and ‘ghostly’ by many travellers2 and, coupled with the orange-lit interior and the way it reflects across the dark water, it signals the devastation of atomic warfare. The A-bomb Dome is also a metaphor for hope.3 As we approach the 70th anniversary of the disaster, it’s harder to remember the post-atomic devastation as downtown Hiroshima has been re-built and is a lively community. As a scholar in literary studies, I turned to atomic bomb literature to try and understand the moments after Pika-don. I focused my attention on hibakusha poetry because of its stark simplicity and the way, like the A-bomb dome, it bears testimony to ‘the most destructive force ever created by humankind; …[while simultaneously] express[ing] the hope for world peace and the ultimate elimination of all nuclear weapons.’4

|

|

There is no direct translation of the word ‘public intellectual’ in Japanese, the closest word is probably chishikijin (知識人) which captures the ‘intellectual’ part of ‘public intellectual’ but stops short of addressing the essential ‘public’ part of this role. However, it is clear that there have been many Japanese across the political spectrum who have fulfilled the same function as the Western public intellectual, such as Mishima Yukio, Ōe Kenzaburō, and Ishihara Shintarō. When hibakusha poets specifically communicate their message of both protest and peace to a large public, via the dissemination of their poetry, they can be identified as public intellectuals.

|

|

|

| Mishima Yukio | Ōe Kenzaburō | Ishihara Shintarō |

Hibakusha who wrote poetry but did not court a broad public for their readership fulfil an important role in the private sphere. No less powerful, their poetry also offers a kind of authentic ‘evidencing’ and recording of the horror of the events of the atomic bombing, but for a smaller and often more personal readership. However, this paper will focus exclusively on those hibakusha poets who sought a public readership. It begins with analysis of atomic bomb poetry to demonstrate the way in which hibakusha poets, such as Kurihara Sadako and Tōge Sankichi can be identified as public intellectuals and ends by discussing outsiderness and simple language as key features of public intellectualism.

A moment in the aftermath of the atomic bomb

Poet Fukagawa Munetoshi stated that in Hiroshima, among writers, it was the poets who most quickly responded to the atomic bombing. He argued that ‘perhaps this was because the Japanese lyric is a conveniently simple genre that could be readily adapted to discussions of the bomb.’5 Certainly, the kind of order that traditional meter prioritizes would have provided some kind of refuge when writing about the chaos that ensued after the dropping of the bomb. Poets may have felt some sense of security writing about tragedy within this ordered frame.

For example, haiku by Ichiki Ryujoshi and Hatanaka Kyokotsu are disciplined and thoughtful. They do not allow for verbosity, rambling or embellishment. Each syllable is carefully chosen to capture a moment in a short and controlled space. It’s a way of paying attention to both the form and the moment that is being expressed. They are visual snapshots of confronting scenes:

Out of the infernal fire corpses in the summer river

業火脱がれ来て夏川の屍となる6

Swollen with burns unable to make a weeping face he weeps

火ぶくれて泣く表情にならず泣く7

Similarly, these two examples of tanka by Koyama Ayao demonstrate control and strong emotion, but the form allows for more detailed expression than haiku. Tanka allows for a longer meditation on an emotional issue and for the use of traditional poetic devices such as metaphor and personification. These tanka focus on the experience of deteriorating health after the atomic bomb. Quite sterile and spare they mirror a hospital’s interior in their containment but the emotion of monitoring the white blood cell count and keeping it hidden is brilliant in its mood of impending doom. These tanka demonstrate a moment in the aftermath of the atomic bomb:

Again and again I count his white blood cells

since it is below several thousand I don’t tell the patient

幾回も繰返し数へし白血球数千に足らざれば患者には云はず

If I know my white blood cell count is decreasing my energy will wither

I don’t check my own

白血球減るとし知らば我が気力衰えぬべし己のは調べず8

Indeed, as John Whittier Treat points out,

many of the first generation of atomic-bomb poets composed in the most traditional of meters with the most conservative choice of words…Such poets turn to the authority of a familiar repertory of symbols (including in the less accomplished examples, clichés) in seeking a concrete idiom for the atrocity and its aftermath.9

However, to counter this tradition, some hibakusha poets searched for new poetic forms to express life in a post-atomic world. Their dissatisfaction with traditional modes of poetic expression stemmed from their belief that what came before the atomic bomb could not convey the experience of atomic warfare. Furthermore, Karen Thornber argues,

Poets felt that haiku and tanka (two of the most popular forms of poetry that were initially used by hibakusha) were taming the experience of atomic warfare beyond recognition and were inadequate for this reason.10

For this reason, poets began to move away from haiku and tanka to free verse. Free verse allowed the poet free reign to experiment with new techniques to represent the rupture and annihilation they had experienced.

|

Kurihara Sadako |

Kurihara Sadako, Tōge Sankichi and free verse

Kurihara Sadako’s poetry confronts the reader in its foregrounding of chaos and violence. After Kurihara experienced the bomb in Hiroshima she made the transformation from shopkeeper to one of Japan’s most controversial poets. Her first major collection of poems, Black Eggs, published in 1946, was highly censored by American Occupation authorities because she dared to address the horrors of the aftermath of the bomb. Edward A. Dougherty states that, ‘American Censors deleted stanzas and whole poems from the book before publication, and because of an earlier run in with Occupation Officials, she herself cut additional materials out.’11 Despite this, it still managed to sell 3,000 copies. The full, uncensored volume of Black Eggs, survived like a ‘fossil’, hibakusha poet Hiromu Morishita observed, until it was re-published, in its restored uncensored format, in 1986.12 Hibakusha poems as ‘fossils’ is a clever metaphor for the way in which the poetry, despite censorship, was preserved. Often published at a later date, these preserved poems provide a unique insight into the A-bomb and its affect on Hiroshima.

|

Kurihara Sadako, Black Eggs |

Kurihara was a political activist and her poetry demonstrates what she has called the ‘dehumanizing logic where Mankind stopped being mankind and completely became a machine.’13 She made a lifetime of ‘cherishing thinking’ and spreading her message of peace. While her life work extends the experience of Hiroshima to discuss Vietnam, the Holocaust and the killing fields of Rwanda, I will focus on her poetry concerning Hiroshima. In her lifetime, she published a substantial body of work, mostly in regional and local venues.

In Black Eggs, the more elegiac poems are expressed in traditional Japanese poetic forms, while free verse, a form just over one hundred years old, is used for the poems that convey anger and violence. It is as if these emotions break the bounds of convention to be liberated in the ‘newer’ free verse.

“City Ravaged by Flames,” written in 1945, is composed as a tanka and ends on the seasonal reference to autumn. The poem primarily evokes sadness and mourning. The use of the word ‘unspoken’ harks back to the argument that tragedy is ineffable or unspeakable:

Amid rubble/ravaged by flames/the last

moments/of thousands:/what sadness!/

Thousands of people,/tens of thousands:

/lost/the instant/the bomb exploded./

silent, all sorrows/unspoken,/city of

rubble/ravaged by flames:/autumn rain falls.14

However, Kurihara has become best known in Japan and internationally for her poem ‘Let Us Be Midwives!’ It prioritises humanism, where, in the center of chaos and destruction, humans reach out to others to ease their suffering. The use of free verse is particularly effective as it allows Kurihara to use many different line lengths, creating a chaotic rhythm to mirror the disorder. This choice of poetic form also allows her free reign to recount a series of moments prioritising realistic dialogue. While the people in this poem act in ‘a concrete structure now in ruins’, in the same way free verse destabilises traditional verse.

Let Us Be Midwives!

—An untold story of the atomic bombing

Night in the basement of a concrete structure now in ruins.

Victims of the atomic bomb

jammed the room;

it was dark—not even a single candle.

The smell of fresh blood, the stench of death,

the closeness of sweaty people, the moans.

From out of all that, lo and behold, a voice:

“The baby’s coming!”

In that hellish basement, at that very moment,

a young woman had gone into labor.

In the dark, without a single match, what to do?

People forgot their own pains, worried about her.

And then: “I’m a midwife. I’ll help with the birth.”

The speaker, seriously injured herself,

had been moaning only moments before.

And so new life was born in the dark of that pit of hell.

And so the midwife died before dawn, still bathed in blood.

Let us be midwives!

Let us be midwives!

Even if we lay down our own lives to do so.15

This poem suggests that there is hope for the next generation with the birth of a ‘new life’; an innocent in what is otherwise a fall from innocence. In her introduction to the 1946 edition of Black Eggs, Kurihara states, ‘behind the emotions of human life lie the ideas that are the essential pillar of human life.’16 In her words, her poetry is about ‘the living moment’.17 She unites ideas and emotion and makes the personal political in ‘Let Us Be Midwives!’

There is no difficult vocabulary in Kurihara’s poetry. It is not jargonistic, nor inaccessible and its simple repetition has assisted in this poem’s endurance. ‘Let us be Midwives!’ is one of the three or four most widely quoted atomic bomb poems. This poem’s value as a response to atomic warfare is immeasurable and its emotion and focus on humanity at the centre of atrocity is incredibly moving.

Written twenty-five years after the dropping of the atomic bomb, Kurihara’s ‘When We Say “Hiroshima”’ plays with the concept of memory and forgetting in its use of repetition. In this poem, Kurihara extends her experience of Hiroshima to comment on world politics. As Kate E. Taylor comments, she ‘unveil[s] the collective amnesia of post-war Japan in ‘When We Say “Hiroshima”’.18 Like a mantra, the use of the word ‘Hiroshima’ is difficult to forget when the poem turns on its repetition:

When We Say “Hiroshima.”

When we say “Hiroshima,”

do people answer, gently,

“Ah, Hiroshima”?

Say “Hiroshima,” and hear “Pearl Harbor.”

Say “Hiroshima,” and hear “Rape of Nanking.”

Say “Hiroshima,” and hear of women and children in Manila

thrown into trenches, doused with gasoline,

and burned alive.

Say “Hiroshima,”

and hear echoes of blood and fire.19

In Kurihara’s poem, the word ‘Hiroshima’ is synonymous with more than just atomic destruction. The poet extends this association across international borders to comment on Pearl Harbour and the Nanking and Manila Massacres. In this way, the poem does more than highlight Japanese culpability in these tragedies but posits that widespread blame and guilt are obstacles to world peace. Indeed, as Thornber argues, ‘Asia’s refusal to forget Japan’s wartime activities’ are presented as ‘wounds everywhere continuing to fester.’20 Kurihara’s confronting images of ‘women and children…doused with gasoline/and burned alive’ and the final words of the stanza, ‘blood and fire’, are reminiscent of descriptions and images of the moments after the atomic bomb in Hiroshima. In these shared images, Kurihara argues for an understanding of all victims of war, regardless of nationality. Makita Yurita argues, ‘for Kurihara’s testimony to be communicated to public spheres, she had to narrate her memory in a context transcending her own nation-state collectivity.’21 This demonstrates her capacity as a public intellectual in the way she was able to reach an international public by extending her experiences to comment on all victims of war.

Say “Hiroshima,”

and we don’t hear, gently,

“Ah, Hiroshima.”

In chorus, Asia’s dead and her voiceless masses

spit out the anger

of all those we made victims.

That we may say “Hiroshima,”

and hear in reply, gently,

“Ah, Hiroshima.”

we must in fact lay down

the arms we were supposed to lay down.

We must get rid of all foreign bases.

Until that day Hiroshima

will be a city of cruelty and bitter bad faith.

And we will be pariahs

Burning with remnant radioactivity.

That we may say “Hiroshima”

and hear in reply, gently,

“Ah, Hiroshima.”

we first must

wash the blood

off our own hands.22

In the second and third stanzas, Kurihara argues that there will never be a ‘gentle’ response to the word ‘Hiroshima’ until Japan ‘washes the blood /off our own hands.’ This final, powerful image further references the way in which Japan has the opportunity to lead the way in reconciliation, particularly in Asia. She argues that it is more than just ‘laying down arms’ and ‘get[ting] rid of all foreign bases’, it relies on the Japanese ridding themselves of any duplicity associated with wartime atrocities by cleansing themselves. This cleansing is implicit in the image of ‘wash[ing] hands’ and is a contentious and rousing statement encouraging activism. Significantly, as Thornber argues, ‘the poet avoids chastising the Japanese by exploring how they might convince the world to be more sympathetic.’23 In this way, the simplicity inherent in Kurihara’s poem makes her arguments about war accessible to a broad and even international public.

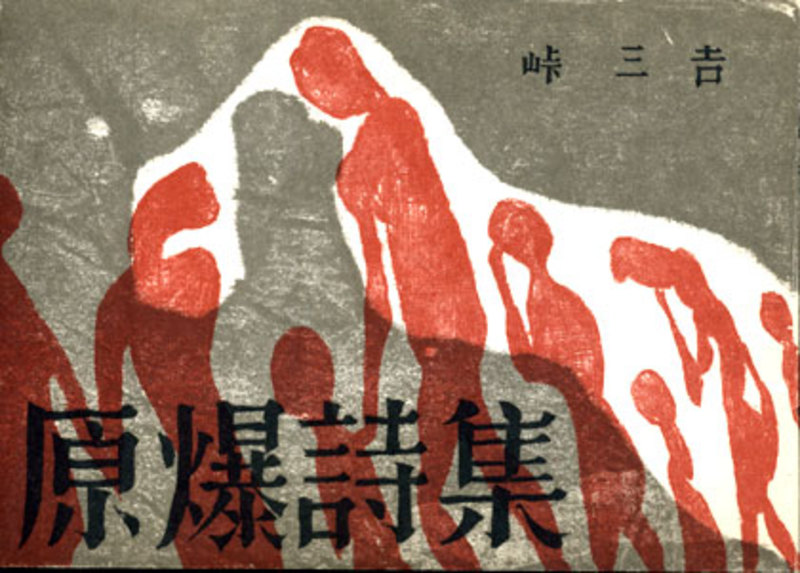

Tōge Sankichi was born in Japan in 1921 and was the most public and politicized of the early Hiroshima poets. He started writing poetry at the age of eighteen and was twenty-four when the A-bomb was dropped on Hiroshima. Tōge died at age thirty-six, a victim of leukemia resulting from the A-bomb and his death lent his poetry further gravitas. His first collection of atomic bomb works, Poems of the Atomic Bomb was published in 1951 and was widely recognized as the leading hibakusha poet of his time.

|

The Poetry of Tōge Sankichi |

At the First-Aid Station

You

Who weep although you have no ducts for tears

Who cry although you have no lips for words

Who wish to clasp

Although you have no skin to touch

You

Limbs twitching, oozing blood and foul secretions

Eyes all puffed-up slits of white

Tatters of underwear

Your only clothing now

Yet with no thought of shame

Ah! How fresh and lovely you all were

A flash of time ago

When you were school girls, a flash ago

Who could believe it now?24

The horrors of atomic warfare are laid bare in the opening lines of this poem. The free verse allows for uneven line lengths, a series of rhetorical questions and the uneven rhythm underlines the unpredictability of the moment. His salute to the ineffability of tragedy is expressed in his juxtaposition of past and present. The past is full of movement and life, whereas the present is represented as confronting war wounds. The opening line, ‘You/Limbs twitching, oozing blood and foul secretions’ is confronting for the reader not only because of its graphicness but also as a result of the use of the second person address. In this way, Tōge invites the reader to experience, vicariously, death in life.

Out from the murky, quivering flames

Of burning, festering Hiroshima

You step, unrecognizable

even to yourselves

You leap and crawl, one by one

Onto this grassy plot

Wisps of hair on bronze bald heads

Into the dust of agony Why have you had to suffer this?

Why this, the cruelest of inflictions?

Was there some purpose?

Why?

You look so monstrous, but could not know

How far removed you are now from mankind25

The middle section of this poem uses a series of rhetorical questions to convey to the reader the pointlessness of atomic warfare. Just as the “you” in Tōge’s poem is unrecognizable, he makes the point that so, too, is the post-atomic world unrecognizable. The use of metaphors allows Tōge the opportunity to compare the monstrous looking victims to the monstrousness of the atomic bomb.

You think:

Perhaps you think

Of mothers and fathers, brothers and sisters

Could even they know you now?

Of sleeping and waking, of breakfast and home

Where the flowers in the hedge scattered in a flash

And even the ashes now have gone

Thinking, thinking, you are thinking

Trapped with friends

who ceased to move, one by one

Thinking when once you were a daughter

A daughter of humanity.26

The simplicity and directness of this poem ensures that the political statement is clear. While its main referent is the atomic bomb, like Kurihara’s poetry, it comments on humanity and the death of innocence in terms of atomic warfare.

Similarly, in ‘August Sixth’, the ‘flash of light’ opens the poem and illuminates the post-atomic horrors in the ensuing lines. A series of broken, overlapping images become more and more abject and shocking as the poem progresses. This is juxtaposed with an emphasis on the numbers of dead in the opening lines where ‘thirty thousand people ceased to be/The cries of fifty thousand killed’:

August Sixth

How could I ever forget

that flash of light!

In a moment thirty thousand people ceased to be

The cries of fifty thousand killed

Through yellow smoke whirling into light

Buildings split, bridges collapsed

Crowded trans burnt as they rolled about

Hiroshima, all full of boundless heaps of embers

Soon after, skin dangling like rags

With hands on breasts

Treading upon the spilt brains

Wearing shreds of burnt

cloth round their loins

There came numberless lines of the naked

All crying

Bodies on the parade ground, scattered like

jumbled stone images

Crowds in piles by the river banks

loaded upon rafts fastened to shore

Turned by and by into corpses

under the scorching sun

in the midst of flame

tossing against the evening sky27

Images of fire and references to heat are twinned with death to intensify the gruesomeness of the moments after the bomb was dropped. The heat only serves to speed up decomposition as the bodies are ‘turned by and by into corpses/under the scorching sun.’ Tōge uses the abject to sear confronting images into the mind of the reader. In this way the ‘skin dangling like rags’ and survivors ‘treading on spilt brains’ are prioritized in the poem. The abject builds to the moment where young, innocent girls lose all dignity in death: ‘Heaps of schoolgirls lying in refuse /Pot-bellied, one-eyed/with half their skin peeled off, bald.’ Their final resting place among refuse, their bellies expanding with the heat and their appearances ghoulish, perhaps the worst part of this image is the end of the innocence that these schoolgirls represent. The second half of the poem moves from more collective remembrances of victims in the first half of the poem to more personal references of families torn apart by the destruction. In this way, a mother and brother are ‘trapped alive under the fallen house’ and a ‘departed wife and child’ are mourned:

Pot-bellied, one-eyed

with half their skin peeled off, bald

The sun shone, and nothing moved

but the buzzing flies in the metal basins

Reeking with stagnant odor

How can I forget that stillness

Prevailing over the city of

three hundred thousand?

Amidst that calm

How can I forget the entreaties

Of the departed wife and child

Through their orbs of eyes

Cutting through our minds and souls?28

‘August Sixth’ is a protest poem that Lifton identifies as ‘less gentle in its protest.’29 With an emphasis on the abject, Tōge strives to preserve in ‘unsparing detail, the force of survivor memories’30. In the line ‘How can I forget’, he entreats the reader to remember.

Public Intellectuals and outsiderness

Outsiderness is an unfortunate feature of the hibakusha experience. During the Allied Occupation of Japan in 1945-52, US censorship ensured that the public was never fully aware of the extent of post-atomic devastation in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. This meant that hibakusha were stigmatised in their own society, largely due to ignorance. Ogawa Setsuko recalled:

As a hibakusha, I was discriminated against. When I went to see a doctor in a hospital, people there sat somewhat apart from me because they thought A-bomb disease was contagious. I was deeply hurt by the prejudice.31

Depending on the extent of their physical injuries, many hibakusha were hidden away and isolated in family homes.

In addition to this discrimination, Lifton discusses the ‘death taint’ and the idea that hibakusha were a threat to people’s own sense of ‘human continuity or symbolic immortality’32. Keloids, scarring and burns were obvious reminders of the A-bomb and its dark legacy. Indeed, Paul Ham argues that keloids ‘had the segregating power of leprosy…the afflicted worked nocturnal jobs out of private shame and public revulsion.’33

When asked in an interview about the hibakusha being chased to the fringes, Nakazawa Keiji, the manga author of Barefoot Gen, stated:

With the discrimination, it came to be the case that you couldn’t talk about having been exposed to the atomic bombing. You simply couldn’t say publicly that you were a hibakusha. The discrimination was fierce. You couldn’t speak out against it…I often heard stories, such as the neighbor’s daughter who hanged herself. Discrimination. Dreadful. There were lots of incidents like that, in which people had lost hope.34

The hibakusha’s outsider status means that when they publish for a large public or publics like Tōge, they can be identified as public intellectuals who act from the margins or even outside society. This is an important feature of Edward Said’s definition of the public intellectual, to which I will return. First, I will provide a frame for the discussion of public intellectualism, discussing the main scholars and points of contention.

The public intellectual existed long before the term ‘public intellectual’ was coined, by C. Wright Mills in his 1958 The Causes of World War Three, where he challenged his peers ‘to act as political intellectuals…as public intellectuals.’35

It is a slippery term that changes over time. Definitions are often either too broad, encompassing anyone who has ever had an idea, or far too narrow to include the full range of public intellectuals. Two key players who brought the discussion of the public intellectual into the public arena are Richard Posner and Russell Jacoby. Posner tries to define public intellectuals in his book, Public Intellectuals: A Study in Decline, numerous times but has been rightly criticized for not prioritizing the ‘intellectual’ part of the public intellectual. Jacoby is cleverer in his refusal to define public intellectual in his book, The Last Intellectuals: American Culture in the Age of Academe, but does suggest that it has something to do with ‘those who cherish thinking and ideas and contribute to open discussions.’36

|

Noam Chomsky |

Noam Chomsky is often identified as the number one living public intellectual.37 I was fortunate enough to interview him at Massachusetts Institute of Technology a few years ago and he was quick to point out that there are two kinds of public intellectuals. He labeled them ‘conformist subservients’ and ‘dissidents’. He argues that the only true public intellectual is the dissident:

If you look through history you will find that it is the conformist intellectuals who are respected, honoured and so on, and in the old Soviet Union, it’s the commissars and not the dissidents; dissidents could be praised in the west but not in the soviet union and it’s the same here, although of course dissidents in the United States aren’t sent to the gulag. We have other ways in the west for marginalising and silencing the voices that aren’t liked. Orwell wrote about that, in his introduction to Animal Farm. He said, in free countries like England, unpopular views can be suppressed without the use of force.38

In the 1993 BBC’s Reith Lectures Edward Said discussed the ‘public role of the intellectual as outsider, ‘amateur,’ and disturber of the status quo’.39 Recalling Julien Benda, he argues that ‘real intellectuals are supposed to risk being burned at the stake, ostracized, or crucified.’40 For Said, ‘The intellectual is an individual endowed with a faculty for representing, embodying, articulating a message, a view, an attitude, philosophy of opinion to, as well as for, a public’.41 Indeed, Said makes the point that ‘exile was an actual, metaphorical and metaphysical condition.’42 Exile, he argues, fosters ‘eccentric angles of vision’43 which hone the public intellectual’s voice and encourages objectivity in the critiquing of society.

Hibakusha poets as public intellectuals

Hibakusha poets can be identified as public intellectuals and contextualised within these definitions when, like Tōge, their poetry reaches a broad public and they take up active public roles. In this way, their poetry turns on this kind of ‘thinking’ and ‘angles of vision’ about atomic warfare and human extinction. A ‘leading’ but unnamed Hiroshima anthologist who spoke to Lifton believed that: ‘poets will emerge from Hiroshima like prophets’.44 Indeed, Chomsky identified ‘prophets’ as dissident intellectuals who were ‘marginalized, tortured, or sent into exile…Intellectuals who dissent remain marginalized in most societies.’45 Therefore, following this line of thought, many poets emerged from Hiroshima like dissident public intellectuals.

First and foremost, a public intellectual needs to be able to reach some kind of public. Without a public, he or she is just an intellectual. Given the American Occupation censorship, the way in which hibakusha poets reached any kind of public is important if they are to be identified as public intellectuals. Monica Braw, author of The Atomic Bomb Suppressed: American Censorship in Occupied Japan, discusses how ‘American censorship was deficient in terms of effectiveness and efficiency’.46 In addition to this, it was not entirely straightforward and was largely open to interpretation. Therefore, despite censorship, some hibakusha poetry was published directly after the dropping of the bomb. This allowed poems like Kurihara’s ‘Let Us Be Midwives!’ to be published, uncensored.

Interestingly, hibakusha poetry has proven incredibly enduring and continues to find new publics with each decade that passes. Books published under American censorship, such as Kurihara Sadako’s Black Eggs, were re-published later, restoring, in many cases, what censors had suppressed. Then anthologies were published and what followed was translation into many different languages and discussion of this poetry all over the world. Scholar, Richard Minear’s translations of Japanese works into English, are particularly significant in this setting as he introduced English speakers to the work of Ota Yōko, Hara Tamiki and Tōge Sankichi. More recently, the internet has allowed for a worldwide online public to experience hibakusha poetry in translation. For example, Tōge Sankichi’s Poems of the Atomic Bomb, translated by Karen Thornber, is free to download as a pdf online.47

The choice of language is one of the most important factors when aiming to reach a public. Many poets cannot be public intellectuals because their poetry uses too much jargon or difficult language to be widely disseminated in the public arena. Hibakusha poetry and indeed much traditional Japanese poetry, such as haiku, however, is not exclusionary in terms of its language. The importance of accessible language for the public intellectual is particularly essential and relevant to the discussion of hibakusha poets because their poetry has been criticised for its use of simple language and its lack of sophistication.48 Tan points out that

all atomic bomb literature have been heavily criticized: that these accounts lack literary qualities and serve as a cheap means for the authors to distinguish themselves, that they are descriptions mainly of political events.49

The use of jargon, however, undermines public dissemination and discussion. This is not to suggest that language needs to be dumbed down for the public, just that impenetrable language prevents public conversation. American public intellectuals Chomsky and Howard Zinn have commented on this, suggesting that jargon is divisive and subversive of public understanding.

I am very impatient with mystification, with pretentious language and a pretty closed circle of people who are the only ones who understand what is being said. One of the important aspects of being a public intellectual is that the public must know what you are saying; must be able to understand what you are saying…Clear concise communication is the most important thing.50

Discussing the language of some intellectuals, which prevents them from being public intellectuals, Chomsky stated:

It is mostly unintelligible gibberish. I look at it, but mostly out of curiosity. It falls into two categories as far as I can see: unintelligible and truism. The truism is said in very inflated rhetoric, polysyllables and so on. What it turns out to be. Is a way for intellectuals to be more radical than thou, but do nothing except talk to each other in academic seminars and not get involved with the general public in real activism…it is a cocoon, almost impenetrable, impossible to understand what they are talking about.51

Identifying hibakusha poets as public intellectuals turns not just on their marginalization and use of poetic language – as this is common to all hibakusha who wrote poetry – but on their ability to reach a public audience and readership. Afflicted by atomic warfare, they were ostracized and wrote about their experiences while being exiles in their own country.

Conclusion

Hibakusha poets’ highly evocative and stirring poetry and their devotion to the abolition of the A-bomb is protest poetry at its most powerful. Whether hibakusha poets can be identified as public intellectuals like Kurihara Sadako and Tōge Sankichi, or private chroniclers of atomic war, they embed important political messages in their poetry. Most importantly, their unwavering focus on world peace provides an enduring reminder of the fragility of human life.

Indeed, in a moving tribute, Mark Selden argues,

If we live in an era that may be called the Nuclear Age, the literary, artistic and citizen representations of the bomb and the hibakusha experience constitute among humanities’ most precious creative achievements, ones that open the path to an epoch of peace and human fulfillment rather than the war and destruction that many have seen as the dominant legacy of the long twentieth century.52

Seven decades after Hiroshima and Nagasaki, as the long-term effects of irradiation and aging take their toll, the number of hibakusha is dwindling rapidly. Hibakusha poets, like Tōge and Kurihara, continue to play roles as public intellectuals by providing new publics via the internet, the opportunity to read their poetry and their message of nuclear disarmament and world peace. Indeed, since the end of Civil Censorship with the end of the occupation, the works of many hibakusha poets have been available and widely disseminated, first in printed form and now on the internet. In this way, their readership continues to grow long after their deaths.

Cassandra Atherton is a writer and critic, and one of Australia’s leading experts on contemporary public intellectuals. She has recently returned from a Visiting Professorship at the Institute of Comparative Culture at Sophia University, Tokyo in 2014 and will take up a Visiting Scholar’s position at Harvard University from August 2015. She has published eight books (with two more in progress) and over the last three years has been invited to edit six special editions of leading refereed journals. She is currently writing a book on Miyazaki Hayao as ‘reluctant’ public intellectual.

Recommended citation: Cassandra Atherton, ‘Give Back Peace That Will Never End’: Hibakusha poets and public intellectuals, The Asia-Pacific Journal Vol. 13, Issue. 23, No. 3, June 08, 2015.

Related articles

• Alexander Brown, Remembering Hiroshima and the Lucky Dragon in Chim↑Pom’s Level 7 feat. “Myth of Tomorrow”

• Daniela Tan, Literature and The Trauma of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

• Elin O’Hara Slavick, After Hiroshima

• John O’Brian, On ひろしま hiroshima: Photographer Ishiuchi Miyako and John O’Brian in Conversation

• Kyoko Selden, Memories of Hiroshima and Nagasaki: Messages from Hibakusha: An Introduction

• Richard Minear, Keiji Nakazawa, Hiroshima: The Autobiography of Barefoot Gen

• Michele Mason, Writing Hiroshima and Nagasaki in the 21st Century: A New Generation of Historical Manga 21

• Nakazawa Keiji, Barefoot Gen, The Atomic Bomb and I: The Hiroshima Legacy

• David McNeill, Expressing the horror of Hiroshima in 17 syllables

Notes

1 ‘Give Back Peace That will Never End’ in Poems by Toge Sankichi: Hibakusha (A-Bomb survivor) Translated by N. Palchikoff. Available as pdf. Retrieved February 17, 2015.

2 Trip Advisor. Retrieved 17 February, 2015.

3 See the UNESCO website. Retrieved 17 February, 2015.

5 John Whittier Treat, Writing Ground Zero: Japanese Literature and the Atomic Bomb, Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1995, p.156

6 Atomic Bomb – Voices from Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Kyoko Iriye Selden and Mark Selden (eds), New York: M.E. Sharpe, Inc., 1989, xxxii.

7 Atomic Bomb – Voices from Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Selden (eds) p.141.

8 Atomic Bomb – Voices from Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Selden (eds) p.135.

9 John Whittier Treat, Writing Ground Zero, p.160.

10 Imag(in)ng the War in Japan: Representing and Responding to Trauma in Postwar Literature and Film, David Stahl and Mark Williams (eds), Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, Hotei Publishing, 2010, p.272.

11 Edward A. Dougherty (commentary), Memories of the Future: The Poetry of Sadako Kurihara and Hiromu Morishita, p3. Available as pdf. Accessed 17 February, 2015, p.5.

12 See ‘Poets Against the War’ website. Retrieved February 17, 2015.

13 Edward A. Dougherty, Memories of the Future, p.5.

14 Kurihara Sadako, Black Eggs, Translated with an introduction and notes by Richard Minear. Ann Arbor, MI: Center for Japanese Studies, University of Michigan, 1994.

15 Kurihara Sadako, Black Eggs, Translated with an introduction and notes by Richard Minear, p.1.

16 Kurihara Sadako, Black Eggs, Translated with an introduction and notes by Richard Minear, p.1.

17 Edward A. Dougherty, Memories of the Future, p.5.

18 Kate E. Taylor, On East Asian Filmmakers, New York: Columbia University Press, 2011.

19 Sadako Kurihara and Richard H. Minear, When We Say ‘Hiroshima’: Selected Poems. Ann Arbor: MI: Center for Japanese Studies at the University of Michigan, 1999. pp20-1.

20 Imag(in)ing the War in Japan: Representing and Responding to Trauma in postwar Literature and Film, David Stahl and Mark Williams Eds., The Netherlands: Brill. Pp284-5.

21 Makito Yurita, Metahistory and Memory: Making/remaking the Knowledge of Hiroshima’s Atomic Bombing, dissertation, Michigan State University, 2008. P107.

22 Sadako Kurihara and Richard H. Minear, When We Say ‘Hiroshima’: Selected Poems, Pp.20-1.

23 Sadako Kurihara and Richard H. Minear, When We Say ‘Hiroshima’: Selected Poems, Pp.20-21.

24 Poems by Toge Sankichi: Hibakusha (A-Bomb survivor) Translated by N. Palchikoff, p.1.

25 Poems by Toge Sankichi: Hibakusha (A-Bomb survivor) Translated by N. Palchikoff, p.1.

26 Poems by Toge Sankichi: Hibakusha (A-Bomb survivor) Translated by N. Palchikoff, p.1.

27 Poems by Toge Sankichi: Hibakusha (A-Bomb survivor) Translated by N. Palchikoff, p.1.

28 Poems by Toge Sankichi: Hibakusha (A-Bomb survivor) Translated by N. Palchikoff, p.1.

29 Lifton, Death in Life, p.441

30 Lifton, Death in Life, p.441.

31 Memories from Hiroshima and Nagasaki: Messages from Hibakusha, The Asahi- Shimbun Company. Retrieved 17 February, 2015.

32 Robert Jay Lifton, The Protean Self: Human Resilience in an Age of Fragmentation, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999, p.29.

33 Paul Ham, Hiroshima Nagasaki: The Real Story of the Atomic Bombings and Their Aftermath, London: Transworld Publishers, 2012, p.440.

34 ‘Barefoot Gen, the Atomic Bomb and I: The Hiroshima Legacy: Nakazawa Keiji interviewed by Asai Motofumi’, Richard Minear (trans.) The Asia Pacific Journal, January 20, 2008. Retrieved 17 February, 2015.

35 C. Wright Mills, The Causes of World War Three, New York: Simon and Schuster 1958, p.124.

36 Russell Jacoby, The Last Intellectuals: American Culture in the Age of Academe, New York: Basic Books, 1987, p.221.

37 Duncan Campbell, ‘Chomsky is Voted World’s Top Public Intellectual’, 18 October, 2005. Retrieved 17 February, 2015.

38 Cassandra Atherton, In So Many Words: Interviews with Writers, Scholars and Intellectuals, Australian Scholarly Publishing, Melbourne, Vic. 2013, p.129.

39 Raphael Sassower, The Price of Public Intellectuals, New Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014, p.44.

40 Sassower, The Price of Public Intellectuals, p.44.

41 Jim McGuigan, Culture and the Public Sphere, London: Routledge, 1996, p.185.

42 Christopher A. Strathman, Romantic Poetry and the Fragmentary Imperative: Schlegel, Byron, Joyce, Blanchot, Albany: State University of New York Press, 2006, p.62.

43 Edward Said, Representations of the Intellectual: The 1993 Reith Lectures, London: Vintage, 1994, p.39.

44 Lifton, Death in Life, p.440.

45 Noam Chomsky, Chomsky on MisEducation, Lanham MD: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, 2000, p.18.

46 Monica Braw, The Atomic Bomb Suppressed: Atomic Censorship in Occupied Japan, New York: M. E. Sharpe, 1991, p.148.

47 TŌGE Sankichi, Poems of the Atomic Bomb (Genbaku shishū), translated by Karen Thornber, 1952. Retrieved 17 February, 2015.

48 John Whittier Treat, Writing Ground Zero: Japanese Literature and the Atomic Bomb, Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1995, p.183.

49 Daniela Tan, ‘Literature and The Trauma of Hiroshima and Nagasaki’, The Asia-Pacific Journal, 12 -40, no.3, October 6, 2014. Retrieved February 17, 2015.

50 Cassandra Atherton, In So Many Words, p.124.

51 Cassandra Atherton, In So Many Words, pp.134-35.

52 Mark Selden, ‘Bombs Bursting in air: State and citizen responses to the US firebombing and Atomic bombing of Japan’, The Asia-Pacific Journal, 12-3, no. 4, January 20, 2014. Retrieved February 17, 2015.