In Bangkok Many Reds Look Beyond Thaksin Toward Revolution: A Photo Essay [updated]

Andre Vltchek from Bangkok

Imagine that you are Thai and poor, as most people in this country still are. Imagine that you are aware of your social position, as most poor Thais are, and that you are educated and understand the complexities and hidden meanings of political life of your country, which most Thais do not. You have basically two alternatives if suicide or emigration is not the option: to support the outrageously elitist aristocracy and the army (many of whose members now paint themselves yellow) whose goal is to preserve society’s feudal arrangements, or support the business tycoon accused of tremendous corruption (his people are painted red). If you can’t chose between these two camps, you are out of luck – nothing else is on the menu.

Applying Marxist logic, the natural evolution of the society is from feudalism to early capitalism, from there to developed capitalism and then, somehow, to socialism.

In Thailand, as in most of Southeast Asia, however, the hybrid of feudalism, royalism and capitalism is now firmly in place. For the elites, the critical goal is to retain their exclusive social and economic position in a society with an enormous divide between the rulers and the majority. It is not just money. Equally important is their exclusive status. For that they will fight, manipulate and even kill thousands.

No writer, above all one who is based in Southeast Asia, can publish a full and honest account of what is happening in Thailand – one free of self-censorship. There are some figures in this country that cannot even be mentioned in connection with anything negative, let alone be criticized. Those who dared to speak and write ended up in this nation’s notorious prisons, an outcome which guarantees broken health.

It is a well-designed system, which guarantees that no citizen and no journalist living or working here will dare to speak up. Thailand offers great rewards to those who choose silence – high quality of life, cheap food, cheap sex and glorious massages, luxurious and affordable serviced apartments and white sand (although increasingly polluted) beaches. No place in Europe or North America offers such bliss for so little cash.

Thailand as a service station for soldiers, business people, foreign press and foreign NGO’s – that was the design developed by the west with Thai collaborators since the beginning of the Vietnam War. The US helped design the present system of power (earlier, the throne was becoming virtually irrelevant).

Thailand became an important base for US forces fighting in Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia, with the Thai military dutifully serving its superpower patron. To serve US troops, tens of thousands of poor Thai women were moved to the brothels of Pattaya and elsewhere. Fierce repression of communists and other leftists followed.

One coup after another devastated the country, but Bangkok was hosting an increasing number of foreign international organizations, NGOs and press agencies. They came fully aware that no criticism of the monarchy would be tolerated, that Thailand as a staunch Cold War ally, would not allow fundamental dissent. The manufacturers of public opinion (the media) as well as NGOs operating in the region and based in Thailand embraced the political mood for their own purposes.

With Thailand playing a signature role in the US-Vietnam War, the nation was subject to an openly undemocratic system, repeated coups, gross violations of human rights of its minorities (some even denied Thai citizenship) and growing sacrifice of its – mostly rural – underclass.

Things began to change when business tycoon Thaksin Shinawatra became Prime Minister in 2001. His business-oriented pragmatism was progressive compared to the stale rule of former elites. He knew that for Thailand to compete with China, Europe or Japan, it needed healthy and educated workers and farmers. During his rule, the quality of education improved dramatically and Thailand introduced a 30 baht (lesser than US$1) per visit medical care system – one of the best in the developing world. Under his 4-year rule, rural poverty was reduced by half – a tremendous boost for the majority but an unforgivable crime in the eyes of the ‘chosen few’. Soon he was seen as a national hero by the poor and as the archenemy by the elites.

It is not that Thaksin was a saint or even a determined defender of the poor. He didn’t hesitate to ‘clean’ the streets of Bangkok during the APEC meeting (October 2003), basically deporting the homeless from the capital to the military barracks. His war on drugs cost at least 2.000 lives, allegedly many of them innocent. During his reign, the conflict (or call it Civil War) in the predominantly Muslim South escalated.

But he was popular and winning against all odds in the confrontation with ‘traditional values’ (read: feudalism). And his country was becoming more egalitarian, scrutinizing its traditional rules.

On 19 September 2006 a military junta calling itself the Council for National Security overthrew Thaksin’s government while he was abroad.

What followed is well-documented: military rule, ‘return to democracy’ in which the pro-Thaksin party won again, Thaksin’s brief return home and further exile, banning of his ruling party by the Supreme Court, and on 26 February 2010, seizure by the Supreme Court of 46 billion baht of his frozen assets. The former Prime Minister became a nomad, living in Dubai, returning to Southeast Asia via Phnom Penh, allegedly holding Montenegrin citizenship.

But through it all, his supporters refused to give up, regrouping and rearranging their bases and strategies, finally uniting under what is now known as the Red Shirts.

The Standoff

Returning again to Thailand, including several days in Bangkok and long hours sharing space with the Red Shirts, my instinct, not hard evidence, dictates that I write these lines: the probably inevitable show-down that is now approaching, probably in a matter of days, perhaps even hours, is not about Thaksin Shinawatra. His name and his image are just among the rallying cries and they are diminishing rapidly.

The people of Thailand – men and women – who came to risk their lives, blocking major intersections in the commercial district, are here to demand justice. Their color is red and red stars now decorate their hats. There are more red stars on the streets controlled by them than images of the deposed Prime Minister. This is another fact widely ignored by foreign media.

Protesters may not know it themselves, but what brought them here are the same grievances and hopes that brought people to the streets of Santiago de Chile in 1970, celebrating the victory of Salvador Allende; the same hopes and grievances that brought Hugo Chavez and Evo Morales to power a few decades later.

They want free medical care and free quality education for their children. They want subsidized housing. And they don’t want to prostrate at the feet of superiors as they were long forced to do.

There is nothing more powerful than to see Thai peasants camping in front of Chloe, Dior, Gucci and other luxury stores, to claim their space and offer their lives for this badly defined but spontaneous revolution.

This rebellion may be crushed tomorrow, coloring Bangkok’s river and canals red with protesters’ blood, but it can also change the course of the history of all Southeast Asia, a region where neo-colonial interests combined with brutal and feudal inertia held entire nations in thrall – a state of affairs supremely comfortable for expatriates, representatives of foreign companies, sexual tourists and a servile press, but degrading for the majority of inhabitants.

When Franco’s fascists encircled Madrid, Czech troops that joined the Republicans used to say: “In Madrid we are fighting for Prague.” There is no doubt that any fight against fascism is international, it is global. Today, Red Shirts are standing guard at their makeshift barricades, built symbolically in front of the country’s major luxury malls. They are here, and some of them may die soon, for their country and social justice for their own people, but without realizing it they may also die for Manila and Jakarta.

What was triggered by a pragmatic, often cynical Prime Minister and business maverick accelerated and gained a momentum of its own. Today, many Red Shirts are ready to fight against feudalism, not for the return of a capitalist tycoon.

Several years ago, in Montevideo, the great Uruguayan writer and icon of the Latin American Left – Eduardo Galeano – told me: “The most terrible crime that could be committed against the poor is to steal their hope. It is even worse than murder. Because hope is often all that poor people have left.”

In the last years, hope was stolen from the Thai poor on several occasions. And the Day of Judgment for that crime is approaching.

Red Thailand: a Photo Essay

I The Red Shirts Defenses

Red Shirts control several key streets in commercial district. This is one of the entrances to their territory, near new Art Center.

Checkpoint erected by the Red shirts.

Makeshift barricade – bamboo and barbed wire. Visible are sharpened bamboo spears that could be used as weapons.

The barricade.

II Life on the Streets

At the entrance to the closed Siam Paragon – Thailand’s most luxurious mall.

Elites fume – this posh Sukumvit Street has long been their playground.

Red women and men bathe in the middle of the once luxury street.

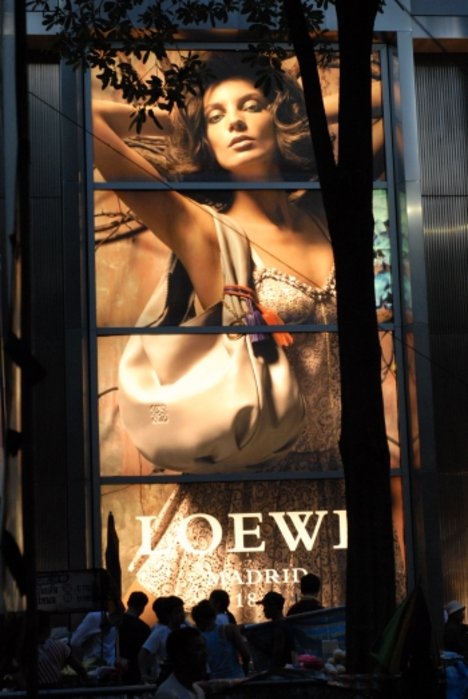

Red Shirts squatting at night in front of Loewe’s.

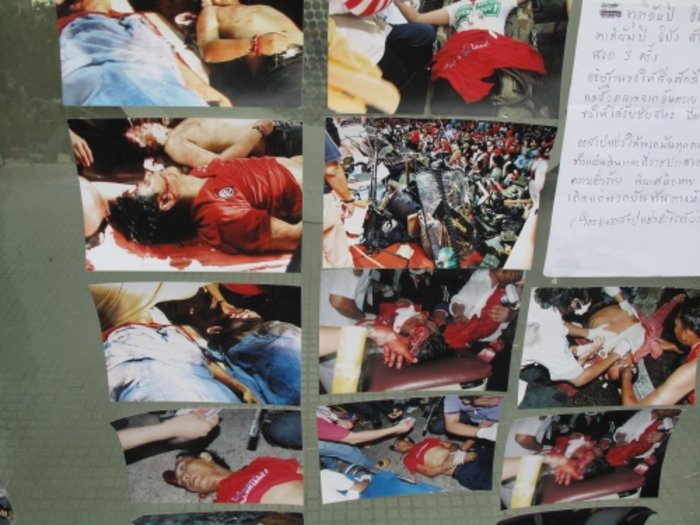

Watching a film about state brutality.

III Media War and Propaganda

Crimes allegedly committed recently by the state .

The current Prime Minister as a vampire.

The current Prime Minister as Adolf Hitler.

Elephants join the fight for democracy too – Red Shirt poster attached to the tail of elephant statue on Siam Square.

Official program of the Red Shirts.

Thai cameraman ready for action.

The main rallying cry of Red Shirts – Peaceful Protesters Not Terrorists.

IV The Military

Hoping not to be ordered to shoot his own people.

Searching for enemies.

Soldiers at key intersections.

V The Red Shirts/The People

Buddhist monk shows allegiance in fashionable Siam Square.

Natthawut Saikua, a leader of the Red Shirts on the night of 28 April.

Red star – not Thaksin – a portrait of a revolutionary.

Memories of times past – hat with Viet Nam worn by Red Shirt protester.

Thai helps Thai – Red Shirt medic treats a young girl.

2 May 2010

VI. Red Shirts

VII. The State

Andre Vltchek is a novelist, filmmaker and journalist, presently residing in and working on Asia and Africa. His latest book, Oceania, was recently published by Expathos and can be reviewed and ordered here. His website is here.

He wrote and photographed this article for The Asia-Pacific Journal.

Recommended citation: Andre Vltchek, “In Bangkok Many Reds Look Beyond Thaksin Toward Revolution,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 18-1-10, May 3, 2010.

For another report from inside Thailand see Joshua Kurlantzick, It’s Not Just Red and Yellow.