War in a Season of Slow Revolution: Defense Lawyers and Lay Judges in Japanese Criminal Justice

David T. Johnson

“Publicity is the very soul of justice…It keeps the judge himself, while trying, on trial.”

Jeremy Bentham (1790)

“You mean they’ll even do shit like this?!”

The future looked grim for Abdy Ismail when his criminal trial started in Osaka District Court on January 17, 2011. Prosecutors believed Ismail was the drug lord who had masterminded the smuggling of 4 kilograms of methamphetamines—with a street value of 350 million yen ($4.2 million)—from Istanbul to the Kansai airport on July 18, 2009, and they wanted to imprison the 42-year-old Iranian for the next 18 years of his life.

Four other defendants in the case (all Japanese) had already been convicted in separate trials, and all would be called as witnesses against Ismail. One was 37-year-old Yamaguchi Tetsuo, who had been sentenced to 13 years imprisonment for his role in this drug smuggling ring. Yamaguchi would testify that he went to the airport with Ismail to pick up the suitcase in which the drugs were hidden, and that Ismail had been trafficking drugs long before his arrest. Prosecutors also had records of hundreds of phone calls that Ismail had made to (they claimed) drug traffickers in Japan and Iran.

Ismail did not confess, but the evidence against him seemed as solid as it usually is when Japanese prosecutors charge a case. When they charge, the result is almost always conviction. Before lay judge trials started in 2009, only about one trial in 800 resulted in acquittal, and even in an unusually “good” year for defendants the proportion was one in 250. The conviction rate was a little lower in cases where defendants did not confess, but even then Japan’s rate of 97 percent was much higher than the rates of 75 to 80 percent that prevail in criminal trials in the United States and United Kingdom.

Around the world, jury and lay judge systems tend to have lower conviction rates than trial systems monopolized by professional judges. But Japan’s conviction rate has not declined under the lay judge system. At the time of Ismail’s trial, nearly 1700 defendants had been adjudicated by lay judge panels, and all but two had been convicted, giving the new system a conviction rate of 99.9 percent. Many analysts believe prosecutors have adopted a more cautious charging policy in order to maintain their high conviction rate under the new (and more unpredictable) adjudication system.1

The chief judge in Ismail’s trial, Higuchi Hiroaki, had presided over lay judge panels that had convicted two of the main witnesses against Ismail. One premise of the prosecution’s theory in those trials was that an unnamed Iranian was the drug kingpin. Thus, to acquit Abdy Ismail would be to cast doubt on the integrity of decisions already made. The theory of cognitive dissonance predicts that this would be difficult for Judge Higuchi and his professional colleagues to do.

It also needs to be noted that Judge Higuchi is held in low esteem in some legal circles. One of Osaka’s leading defense lawyers told me that Higuchi is a “terrible judge” (hidoi saibankan) because he routinely favors the prosecution, and another said he is “the worst judge in Osaka” (Osaka chisai no saiaku no saibankan). A third lawyer told me that when he and his peers were training as legal apprentices (shiho shushusei) in Higuchi’s chambers, the Judge repeatedly stressed that a good lawyer does three things: consents to prosecutors’ requests to use written statements as evidence at trial (doi suru), approves other requests made by the prosecution and the judge (shikaru beki), and encourages suspects and defendants to admit the charges against them (mitomeru). In short, Higuchi believes that the proper role of a defense lawyer is simply to go with the flow as it is defined and desired by the state.2

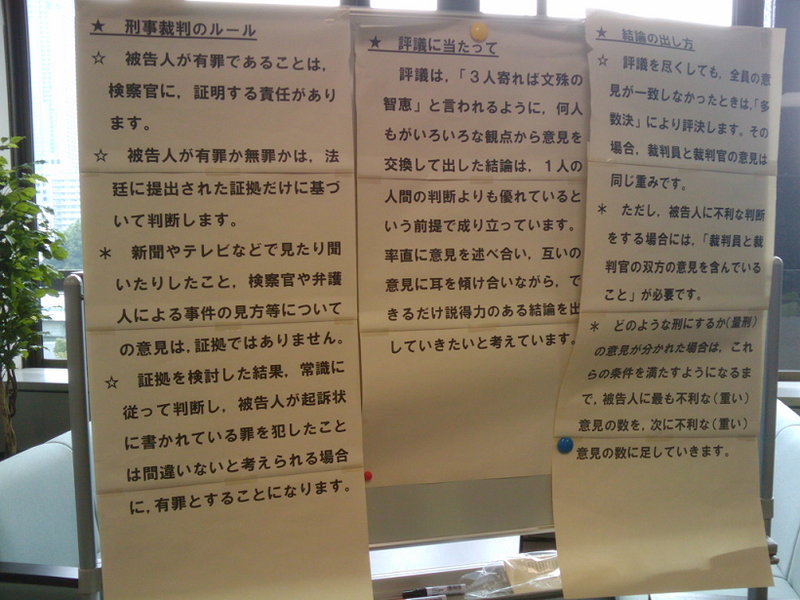

Then there are the views of Takano Takashi, a veteran attorney who established Japan’s Miranda Association (Miranda no Kai)3 and who leads the Japan Federation of Bar Association’s efforts to train lawyers in trial advocacy. In August 2010, Takano was conducting a training course in Osaka, and as luck would have it he happened to eat lunch in a deliberation room (hyogishitsu) used by Judge Higuchi and his colleagues. On entering the room Takano was pleased to see that “Rules for Criminal Trials” had been posted on a whiteboard, presumably to instruct citizen-judges who are amateurs in the law. But the more Takano studied the Rules the more concerned he became (see photograph). Incredibly, the whiteboard presented guidelines for convicting defendants but omitted language about when it is appropriate to acquit.4 In Takano’s words:

“I was amazed. I trembled a little. And I was indignant. You mean they’ll even do shit like this?! This is what I cried out in my heart. If judges feel like it, they can use clever methods in the secrecy of the deliberation room to lead lay judges to their preferred conclusion without anyone noticing. This is precisely the fatal danger of the lay judge system that does not exist in a jury system [because professional judges do not participate in deliberations when there is a jury system].”

|

Judge Higuchi Hiroaki’s “Rules for Criminal Trials” |

Dogs That Do Not Bark

In Arthur Conan Doyle’s story of “Silver Blaze,” detective Sherlock Holmes notices that a dog did not bark during the theft of a horse. The canine’s silence means the thief was not a stranger, which reduces the number of suspects to one. Case closed.

Inspector Gregory of Scotland Yard: You consider this to be important?

Sherlock Holmes: Exceedingly so.

Inspector Gregory: Is there any point to which you would wish to draw my attention?

Sherlock Holmes: To the curious incident of the dog in the night-time.

Inspector Gregory: The dog did nothing in the night-time.

Sherlock Holmes: That was the curious incident.

I am no Sherlock Holmes, but I have been studying Japanese criminal justice for the last 25 years. To me, the most curious thing about Japan’s current reform debate is how much pressure is being directed at prosecutors and how little at judges and defense lawyers. Prosecution certainly needs reform.5 Most importantly, interrogations should be recorded from start to finish. There are many good reasons to require this—and there is no good reason not to.6 When more than one-quarter of prosecutors acknowledge that they have been directed by a superior to create a dossier that differs from what a suspect or witness actually told them, the imperative of reform is painfully apparent.7

But prosecutors are only part of a “criminal court community” that is also inhabited by judges and defense lawyers. If prosecutors dominate this community, it is partly because judges and defense lawyers have allowed them to. Much talk about criminal justice reform overlooks the crucial fact that judges and defense lawyers have frequently failed to perform their duty to check prosecutors’ power in the criminal process.

Deferent Judges

Judges have the final word in Japanese criminal justice, and they routinely use it to give prosecutors (and police) what they want: arrest warrants, detention warrants, evidence admitted at trial, and convictions. Moreover, when prosecutors do not get what they want from lower courts, they frequently get it on appeal. There is nothing necessary or inevitable about this tendency. Indeed, postwar reforms seemed to create significant safeguards for criminal suspects and defendants. But as Tokyo University Professor of Law Daniel Foote has observed, in translating the “law on the books” into “law in action,” Japan’s judiciary “adopted, accepted, or silently acquiesced in a wide range of interpretations that greatly circumscribed the protections for suspects and defendants, while granting broad authority to investigators.”8

This—the extraordinary deference of judges to prosecutors—is why defense lawyer Takano Takashi says that if he could change only one thing about Japan’s criminal justice system, it would be the tendency of judges to yield to prosecutors in their decision-making. In his view, judges do this so “reflexively and routinely” that “reforming the judiciary is even more urgent than reforming the procuracy.” “If judges change,” Takano believes, “prosecutors will too” (author’s interview).

Passive Attorneys

The reform dogs have also failed to bark about defense lawyers, whose obligation it is to try, by every fair and legal means, to get the best result for their clients. This duty is routinely respected in the breach. A foreign defendant in Kobe once told me that his defense lawyer—one of the most highly respected in that city of 1.5 million—“is as good as tits on a bull.” His comment captures an uncomfortable truth. For decades, many defense lawyers have been little more than passive props in trial ceremonies that are scripted by prosecutors, certified by judges, and barely contested by the defense. This passivity has been recognized by lay judges, who report much more dissatisfaction with defense lawyers’ activities than they do with those of the prosecution.9

There are many reasons for this passivity, including some over which defense lawyers have little or no control. For one thing, judicial interpretations of law have severely restricted what defense attorneys can do for criminal suspects and defendants. For another, all but a few criminal cases pay poorly in comparison to the other work opportunities that Japanese attorneys have. In criminal defense as in other areas of life, sometimes you get what you pay for.10

But if law and economics are formidable structural obstacles to good defense lawyering, the cultural obstacles are also important. Indeed, defense lawyers are complicit in a state of affairs which Hirano Ryuichi, former president of Tokyo University and the dean of criminal justice studies in Japan, described as “abnormal,” “diseased,” and “really quite hopeless.”11 Most notably, Japanese defense lawyers seldom advise suspects or defendants to invoke their right to silence. For example, a survey of more than 1000 lawyers in 1991 found that over 60 percent had never recommended that a suspect or defendant exercise the right to remain silent. Not a single time.12

Since it is often in a suspect’s best interest not to talk to interrogators, it is unclear what lies behind this reluctance to recommend such a fundamental right. One cause is surely the difficulty of maintaining silence through Japan’s long interrogation process. As one attorney told me, “if I advised 100 suspects to remain silent, only one or two would be capable of staying mute until interrogations end.” Japan’s criminal process is designed to facilitate the extraction of confessions, and a confession is still widely considered “the king of evidence.” Nonetheless, in many criminal cases the best thing a defendant can do is what is urged by a full-page advertisement (under “Attorneys”) in the Boston Yellow Pages: JUST SHUT UP.

It is also striking how little vigorous advocacy there is even in trials where defendants claim innocence. In a rape trial I watched some years ago in which the defendant insisted that the victim consented to sex, a defense lawyer scolded his client in open court. “Who are you trying to kid?” the attorney asked the befuddled defendant. “Do you really think anyone is going to believe your story? I don’t. Do you think the judges are convinced? Come on. That’s really far-fetched. At least tell the judges a better story than that.” And in a murder trial I recently watched in which prosecutors sought a sentence of death for a defendant who had a prior conviction for homicide, the defense lawyers passed up numerous opportunities to press the prosecution’s witnesses about weaknesses in their testimony. Their cross-examination of key witnesses frequently finished in a few minutes. With friends like this, who needs enemies?13

“Extremely inappropriate!”

It is difficult to defend criminal cases in a country where the criminal process is severely tilted in favor of state interests. It also needs to be acknowledged that there is not one right way to do criminal defense. A lot depends on the case and the context—and Japan is not the United States.14 But sometimes the best defense is a good offense,15 even in Japan.

On the fourth day of Abdy Ismail’s trial, defense lawyer Kobayashi Tetsuya went on the offensive. Kobayashi had already poked several holes in the prosecution’s case, but on the previous day Judge Higuchi had asked a series of questions to the prosecution’s key witness (Yamaguchi) which seemed rooted in a conviction that Ismail was a drug lord. “Oh man,” Kobayashi told me during one break in the proceedings. “I can’t believe this. This judge acts just like a prosecutor.”

When hearings resumed on the morning of January 20, Kobayashi asked Judge Higuchi for permission to read a statement to the court. The judge granted permission and then tried to take it back as soon as he realized what Kobayashi wanted to say. But it was too late. Kobayashi just kept reading:

“As this trial proceeds, I have something that I really want to say to the judges and lay judges. As I spoke in my opening statement, the central dispute in this case is about the reliability of Yamaguchi’s testimony. To put it simply, the key issue is whether he spoke the whole truth and nothing but the truth. I am a defense lawyer, but no matter how hard I try to listen neutrally to his testimony, I cannot believe that Yamaguchi came clean. It is also clear that his testimony will become the center of your deliberations.

However, yesterday when the chief judge asked Yamaguchi “why did you decide to speak the truth?” he assumed this witness was telling the truth. That assumption has no foundation in fact, and it was extremely inappropriate for a judge to reveal to lay judges his own impression about the central issue in dispute at this trial. Not only that, but the judge sent out lots of lifeboats to the prosecution in order to rescue their case after I exposed irregularities in Yamaguchi’s testimony during my cross-examination. The judge even went so far as to ask Yamaguchi about abstract issues that the witness had not even mentioned in his testimony—‘underground banks’ and ‘improved cash flows’ and the like—without even bothering to confirm the details with Yamaguchi.

At a trial stage when the court is still hearing evidence and not yet deliberating about a verdict, the judge’s questions were premised on an assumption of guilt. This was an effort to cement impressions and appearances, and it cannot possibly be called fair. When the judge examines witnesses during the rest of this trial, I demand that he not ask questions or make leading statements that are rooted in prejudice.

I also would like to make a request to the lay judges. Professional judges do not necessarily make correct judgments. In fact, justice has often miscarried in trials conducted solely by professional judges. The introduction of the lay judge system is meant to check unreasonable judgments that violate the common sense of society. No matter what the chief judge says during deliberations, please state your own views with confidence.”

I have watched at least 50 criminal trials in the last 25 years, and this was the most powerful appeal I have ever heard. It commanded the attention of everyone in the courtroom—including Judge Higuchi, who became much meeker after this scolding. I have to commend Kobayashi for his principle and pluck, and I also have to wonder why more Japanese defense lawyers do not make similarly forceful arguments. If Japan’s criminal process is in fact “diseased” (as Professor Hirano concluded), then arguments like Kobayashi’s must be one critical part of the cure.

Defending someone accused of a crime is not a job for people seeking approval. It is a job for those who are willing to rattle cages, make enemies, and raise hell. By raising hell, defense lawyers honor the law.

The need to “rattle cages” is also what defense lawyer Takano Takashi had in mind when he told me that the lay judge system gives defense lawyers a precious opportunity to improve a system that sorely needs change:

“The advent of the lay judge system marks the beginning of a war (tatakai) against professional judges. Judges are trying to minimize the scope of lay judges’ authority. This is what Judge Higuchi was trying to do with his Swiss-cheese-like ‘instructions’ to lay judges. And it is not just him. Many professional judges want to minimize the scope and significance of the lay judge reform. But this is a power struggle. [If we are to fulfill our trust of protecting the rights of our clients,] we defense lawyers must empower lay judges to stand up to professional judges and defeat them in the deliberation room. For this to happen, defense lawyers must shed the feeling of uselessness that has been their biggest burden. Defense lawyers are habituated to being passive in the criminal process. We have been socialized to believe that what we do does not matter. But with lay judges in front of us, we are no longer talking to a wall. Now we have a real opportunity to make a difference, and we need to make the most of it. We must fight in open court to change a system that is stacked against us.”

“A stone into the pond”

Abdy Ismail was acquitted. It is impossible to know whether lay judges “defeated” professional judges in the deliberation room where his fate was decided, because a confidentiality rule requires lay judges to remain forever silent about what went on there. This rule should be relaxed when the lay judge system is formally reviewed in 2012. Until the “black box” of deliberations is opened, one can only speculate about what occurs in this critical stage of the criminal process.

But in other stages of the criminal process the lay judge system is already transforming some of the standard operating procedures that have long defined Japan’s system of “prosecutor justice” (kensatsu shiho). As Kokugakuin University Professor of Law Shinomiya Satoru observes, the lay judge system “has thrown a stone into the pond” of Japanese criminal justice, and “the ripples are gradually spreading.”16

For example, because citizens cannot be asked to serve for weeks or months at trial, a pretrial process was created to narrow and define the issues that will be contested in court. This has had many effects, including a major improvement in the amount of evidence that prosecutors disclose to the defense before a trial begins. Another welcome development is progress toward recording interrogations—and more progress will be made in the months and years to come (as Bob Dylan sings in Subterranean Homesick Blues, “you don’t need a weather man to know which way the wind blows”). The movement to record interrogations has multiple causes, including troubling revelations in recently revealed miscarriages of justice (Muraki, Ashikaga, Fukawa, and Shibushi), but without the lay judge system the recording reform would still be on the distant horizon.17

The lay judge stone has caused other ripples as well. Bail has become easier to obtain as judges start to recognize the dangers of a system of “kidnap justice” (hitojichi shiho) in which pretrial detention is deemed necessary for defendants who do not confess. Trials are much easier to understand than they used to be—and much less reliant on essays (chosho) composed by police and prosecutors behind the closed doors of an interrogation room. Access to defense lawyers has improved, especially in the critical pre-trial period, and one consequence is that suspects are becoming less cooperative during interrogations.18 Bar associations are also training defense lawyers to become more effective advocates at trial. These changes began before the lay judge system started, they have accelerated since, and they will probably continue to transform criminal justice in the years to come.19

How courts find facts is one of the most fundamental features of any system of criminal justice. Moreover, legal systems will tolerate almost anything before they will admit the need for reform in their methods of proof and trial. Japan has already changed its system of proof and trial for the serious criminal cases that are adjudicated by lay judge panels.20 This was a big step, and it will have effects throughout the criminal process. It will also take time for the full effects to appear. If there is going to be a revolution in Japanese criminal justice, it will probably be a slow one.

“The horrible thing about all legal officials”

At least five of the nine persons who judged Abdy Ismail believed there was reasonable doubt about his guilt. According to the court’s opinion, testimony that Ismail is a drug kingpin “lacked reliability” and may have “concealed the truth about the existence of a different leader.” In reaching this conclusion, the court accepted Kobayashi’s claim that the investigation was “extremely shoddy” because it failed to consider the possibility of yakuza involvement in a smuggling operation of this scale. In Japan, when you find 4 kilograms of methamphetamines, you expect to find tattoos and missing fingers somewhere near the scene of the crime. This is the common sense of Japanese society, and prosecutors ignored it.

Acquittals in Japan are usually attributed to deficiencies in the prosecution rather than to proficiencies in the defense. Defense lawyers do not win cases; prosecutors lose them. This view reflects the prevailing assumption that defense lawyers do not really matter.

But defense lawyers are not replaceable parts. Without Kobayashi—or another defense attorney similarly skilled and motivated—there would have been no acquittal. His passion, preparation, and willingness to “rattle cages and raise hell” go a long way toward explaining why Abdy Ismail is now a free man (though prosecutors have appealed his acquittal).21

Another important cause of this acquittal was the presence of six citizens in the deliberation room where Ismail’s fate was decided. Kobayashi had implored them to state their own views with confidence, and apparently they did just that. In Kobayashi’s view, without the fresh perspectives of the lay judges, “this case would have been completely hopeless” (author’s interview).

The fresh eyes of the amateur are important because in law as in life, the more one looks at a thing, the less one sees it. As G. K. Chesterton observed a century ago:

“It is a terrible business to mark a man out for the vengeance of men. But it is a thing to which a man can grow accustomed, as he can to other terrible things…The horrible thing about all legal officials—even the best—about all judges, magistrates, barristers, detectives, and policemen, is not that they are wicked (some of them are good), and not that they are stupid (several of them are quite intelligent). It is simply that they have got used to it. Strictly, they do not see the prisoner in the dock; all they see is the usual man in the usual place. They do not see the awful court of judgment; they only see their own workshop.”22

I do not think Judge Higuchi is “wicked” or “stupid.” He—and many other Japanese judges—have simply “got used to” presuming that “the usual man in the usual place” is, as usual, guilty. A conviction rate close to 100 percent testifies to this terrible tendency, and so does a recent survey which found that not a single prosecutor out of 40 believes the high conviction rate reflects problems in the judiciary.23 But if prosecutors regard the conviction rate as a point of pride, it should be cause for serious reflection among their brothers and sisters on the bench.

Defense lawyers have also grown accustomed to being passive in the criminal process. Many of them do not appreciate how awful “the awful court of judgment” can be for the person being judged. For criminal defendants, the right to an attorney is the most fundamental right because it is the one that makes all of their other rights meaningful. If defense lawyers fail to take up the call to arms that Takashi Takano has issued, other reforms—no matter how well intentioned—will probably end in disappointment. Rights are rarely bequeathed by benevolent authorities; they emerge out of experiences with injustice, and getting them recognized usually requires raising a little hell.24

There is considerable pessimism about Japanese criminal justice. The conviction rate remains very high, even in lay judge trials that are contested by the defense. And if the propensity to appeal lay judge decisions can be taken as a measure of dissatisfaction with the new system, then the fact that defendants appeal about 300 out of every 1000 outcomes while prosecutors appeal only 3 seems to suggest that the new system is mainly doing what prosecutors want.25 Could it be that the more things change in Japanese criminal justice, the more they will stay the same?

Yet there may also be room for optimism. As Abdy Ismail’s acquittal suggests, the lay judge system can correct the judicial tendency to see “the awful court of judgment” as one’s own familiar workshop, and some defense lawyers are starting to realize that they are no longer “talking to a wall.” Perhaps the cages have started to rattle—and maybe the ripples of reform will continue to spread.

David T. Johnson, Professor of Sociology, University of Hawaii; [email protected]

He is co-author (with Franklin E. Zimring) of The Next Frontier: National Development, Political Change, and the Death Penalty in Asia (Oxford University Press, 2009). This is a revised and expanded version of an article that first appeared in Japanese in the monthly magazine Sekai, as “Keiji Bengoshi to Saibanin Seido: Henkaku no Naka no Toso” (No. 819, July 2011), pp.266-275.

Recommended citation: David T. Johnson, War in a Season of Slow Revolution: Defense Lawyers and Lay Judges in Japanese Criminal Justice, The Asia-Pacific Journal Vol 9, Issue 26 No 2, June 27, 2011.

Notes

1 As of May 21, 2011—the second birthday of Japan’s lay judge system—2126 defendants had been tried by the new system, of which 2118 had been convicted on all charges. This is a conviction rate of 99.6 percent. Sankei Shimbun, “1man 1889nin ga Taiken: Muzai 8nin,” May 21, 2011, p.22. On the reasons for Japan’s high conviction rates, see David T. Johnson, The Japanese Way of Justice: Prosecuting Crime in Japan (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002), ch.7.

2 One lawyer in Osaka believes Judge Higuchi should not be singled out for special criticism because the problem of pro-prosecution judges is pervasive in Japan (author’s interview). He is right about the general point—Japanese judges defer to prosecutors all too often—but in my view, the critical comments about Higuchi merit mention because many lawyers in Osaka seem to share this censorious assessment and because (as the quotation from Jeremy Bentham that opens this article suggests) judges must be held accountable one judge at a time.

3 Founded in 1992, the Miranda Association aims to protect the rights of criminal suspects and defendants, much as the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1996 Miranda v. Arizona decision attempts to do. Attorneys in the Association employ three main strategies: they advise suspects to refuse to be interrogated; they advise suspects to refuse to sign any written statements (chosho) that are made during interrogation; and, when written statements have been made by police and prosecutors, they resist their introduction as evidence at trial. Japan’s Miranda Association has had little success recruiting lawyers to participate in the organization or influencing lawyers to adopt these tactics (author’s interviews with Takano Takashi, and David T. Johnson, The Japanese Way of Justice: Prosecuting Crime in Japan (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002), pp.77-79).

4 Here are some of the phrases in the Supreme Court’s guidelines for lay judges that were omitted on the whiteboard in Osaka: “ですから、検察官が有罪であることを証明できない場合には、無罪の判断を行うことになります…裁判では、不確かなことで人を処罰することは許されません…逆に、常識に従って判断し、有罪とすることについて疑問があるときは、無罪としなければなりません” (link). Translation by the author: “Thus, when the prosecution cannot prove guilt, a judgment of not guilty must be rendered…In a trial, it is impermissible to punish a person who is not certainly guilty…Conversely, when there is doubt about guilt after making judgments based on common sense, the defendant must be acquitted.”

5 Jeff Kingston, “Justice on Trial: Japanese Prosecutors Under Fire,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 9, Issue 10, No. 1, March 7, 2011.

6 Ibusuki Makoto, Higisha Torishirabe to Rokuga Seido: Torishirabe no Rokuga ga Nihon no Keiji Shiho o Kaeru. (Tokyo: Shojihomu, 2010).

7 Asahi Shimbun, “Kenji 26% ‘Shiji Sareta Keiken’: Jissai no Kyojutsu to Kotonaru Chosho no Sakusei,” March 11, 2011, p.38.

8 Daniel H. Foote, “Policymaking by the Japanese Judiciary in the Criminal Justice Field,” Hoshakaigaku, No.72 (2010), p.18.

9 Niben Frontier, “Kisha wa Ko Miru Saibainin Saiban,” March 2011, pp.21-34.

10 David T. Johnson, The Japanese Way of Justice: Prosecuting Crime in Japan (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002), pp.71-85.

11 Hirano Ryuichi. “Diagnosis of the Current Code of Criminal Procedure.” Law in Japan. Vol. 22 (1989), pp.129-142.

12 The same survey found that 66 percent of lawyers had never demanded that a witness testify in court when prosecutors sought to rely on a written statement (chosho), and 75 percent had never requested a court order compelling disclosure of evidence.

13 For more analysis of the challenges faced by defense lawyers in Japan, see The Japanese Way of Justice: Prosecuting Crime in Japan (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002), pp.71-85; “Early Returns from Japan’s New Criminal Trials,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, vol. 36-3-09 (2009), pp.1-17; and “Capital Punishment without Capital Trials in Japan’s Lay Judge System,” Asia Pacific Journal, Vol. 8, Issue 52 (2010), pp.1-38.

14 In some ways, the United States is a poor model for reform of criminal defense in Japan. See, for example, The Constitution Project, “Justice Denied: America’s Continuing Neglect of our Constitutional Right to Counsel: Report of the National Right to Counsel Committee,” April 2009, pp.1-219, link. But the quality of American defense lawyering also varies from place to place. For a description of serious problems in Detroit’s public defender system, see Ailsa Chang, “Not Enough Money or Time to Defend Detroit’s Poor,” August 17, 2009. For a portrait of more aggressive and effective public defenders working in the South Bronx, see David Feige, Indefensible: One Lawyer’s Journey Into the Inferno of American Justice (New York: Little, Brown, & Company, 2006).

15 Alan Dershowitz, The Best Defense (New York: Vintage, 1983).

16 Shinomiya Satoru, “Defying Experts’ Predictions, Identifying Themselves as Sovereign: Citizens’ Responses to Their Service as Lay Judges in Japan,” Social Science Japan, No. 43 (2010), p.13.

17 In addition to the lay judge system and miscarriages of justice, two other causes are encouraging recording reforms in Japan: the international movement towards recording (Japan is riding this wave, albeit less rapidly than South Korea, which has a similar criminal justice system), and the movement towards increased transparency in Japanese society. In this context, it is doubly disappointing that the Kensatsu Arikata Kento Kaigi did not recommend recording interrogations in their entirety, and that Minister of Justice Eda Satsuki has not imposed a meaningful recording requirement on prosecutors (though he has encouraged them to start “experimenting”). Police resistance to recording reforms is similarly stubborn. See Kensatsu Kento Kaigi, “Kensatsu no Saisei ni Mukete: Kensatsu no Arikata Kento Kaigi Teigen,” March 31, 2011.

18 In a national survey of 1444 prosecutors, 82 percent of them said “it has become more difficult to obtain statements from suspects and witnesses.” Tokyo Shimbun, “26% ga ‘Shiji Sareta’: Kyojutsu to Chigau Kenji Chosho Sakusei,” March 11, 2011, p.1.

19 Shinomiya Satoru, “Saibaninho wa Keiji Jitsumu no Genba ni Nani o Motarashite Iru ka,” Hogaku Semina, No.644 (2008), pp.1-3.

20 Lay judge panels preside in about 3 percent of all criminal trials. The other 97 percent of criminal trials are heard by a single professional judge or a panel of three professional judges.

21 Prosecutors in Ismail’s case have asked the Osaka High Court to do for them what judges in the Tokyo High Court did for prosecutors in the first lay judge acquittal: convict the defendant and sentence him to a long term of imprisonment. In a methamphetamine smuggling case in Tokyo, the Tokyo High Court imposed a sentence of 10 years on a defendant who had been acquitted by a lay judge panel in Chiba. See Sankei Shimbun, “Saibanin Saiban de Muzai no Otoko ni Gyakuten Yuzai: Zenmen Muzai no Haki wa Hajimete: Tokyo Kosai,” March 30, 2011. Some observers hope that this kind of judicial deference to prosecutors at the appellate level will not become the norm, but there is reason to worry. One day before the Chiba methamphetamine acquittal was reversed, a different panel of professional judges on the Tokyo High Court remanded a case to the Tokyo District Court for retrial. In this case, the defendant had been acquitted of arson by a lay judge panel in Tokyo. See Asahi Shimbun, “Kosai, Hajimete no Haki Sashimodoshi: Saibanin Saiban no Muzai Hanketsu,” March 30, 2011.

22 G. K. Chesterton, “The Twelve Men,” in Tremendous Trifles, 1909. Analysis of Chesterton’s quotation also appears in David T. Johnson, “Early Returns from Japan’s New Criminal Trials,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 36-3-09, September 7, 2009.

23 Mainichi Shimbun, “Kenji Ankeeto,” March 9, 2011, p.25.

24 Alan Dershowitz, Rights from Wrongs: The Origins of Human Rights in the Experience of Injustice (Basic Books, 2005).

25 Mainichi Shimbun, “Seido 2nen Jisshi Jokyo,” May 21, 2011, p.25. In Japan, the defense and the prosecution can appeal both sentence and verdict.