High Stakes Gamble as Japan, China and the U.S. Spar in the East and South China Seas

Peter Lee

In China’s international relations, 2010 has been the Year of Zero Sum.

On a series of issues, the Western and Asian democracies have demanded that China accept policies that advance their agendas while sacrificing Chinese interests.

On one level this is the inevitable outcome of the Obama administration’s repositioning of its foreign policy away from the amoral, Westphalian-style horse-trading of national interests of the Bush administration.

The United States has now established global adherence to norms championed by the U.S. and its allies—non-proliferation, global warming, democracy, freedom of information, freedom of navigation, open currency markets, and human rights—as the cornerstone of its foreign policy. This does not necessarily mean, of course, that the U.S. holds itself or its allies to such high standards in these realms, notably global warming, but even human rights and freedom of navigation.

By accident or design, the insistence on these norms as the driver behind global policy leaves nations, particularly an authoritarian government like the PRC, which is outside of the U.S.-defined mainstream on virtually all of these issues, little scope to define and advance its competing national interests as legitimate.

It also has the effect of isolating China from Western and some Asian democracies—a useful geopolitical windfall for nations anxious about China’s rising economic, military, and geopolitical clout and the global gains Beijing made in the first decade of the 20th century while the Bush administration was asleep at the Asian switch.

In 2010, China was called upon to sacrifice its own interests on virtually all of the Obama administration’s key initiatives. On global warming, China was asked to abandon the highly favorable terms of the Kyoto Protocol for an economically costly cap on its greenhouse gas emissions even as the U.S. failed to commit to any significant controls. On the issue of Google, the Obama administration (which counts a significant number of Google insiders in its tech-policy brain trust) called on China to tear down that Great Firewall, something that China considers an unacceptable political risk.

On Iran, China was pressed to put its energy security and alliance with Iran at risk in order to join the U.S.-led crusade against Iran’s nuclear ambitions. On North Korea, China was told to abandon its useful buffer, the DPRK, and join a chorus of condemnation over the sinking of the Cheonan that would shift the focus toward the reunification of the peninsula under the aegis of the United States and the ROK. On currency, the U.S. has demanded that China substantially appreciate its currency with the anticipated result of reducing its exports so the United States can try to find a way out of its economic difficulties.

Not only did the PRC resist American pressures on each of these fronts, but it also summoned up the energy to protest the awarding of the Nobel Peace Prize to Liu Xiaobo, the imprisoned activist, whose organization receives funding from the U.S. government’s National Endowment for Democracy, whose candidacy was championed by the PRC’s arch-foe, the Dalai Lama, and whose platform calls for replacing the PRC’s political monopoly with a multi-party democracy.

And then there is the issue of the island groups.

The East and South China Seas are home to dozens of contested islands, atolls, and sandbars, virtually all of them uninhabited. China has asserted sovereignty over virtually the entire area, including two potential flashpoints: the Paracels, which it seized from South Vietnam in 1974, and the Diaoyutai/Senkaku Islands, which have been firmly under Japanese sovereignty (with an interlude of American occupation) since 1895.

The situation in the Paracels—and China’s patent unwillingness to negotiate on the question of the islands while asserting effective sovereignty through measures like organizing Paracels tourism—has provoked the strong resentment of the Vietnamese government. For several years, Vietnam has attempted to cultivate a relationship with the United States and involve Washington on its side in the dispute. This was a temptation the U.S. resisted until this year, when Secretary of State Hillary Clinton declared that the United States had “a national interest” in freedom of navigation in the South China Sea.

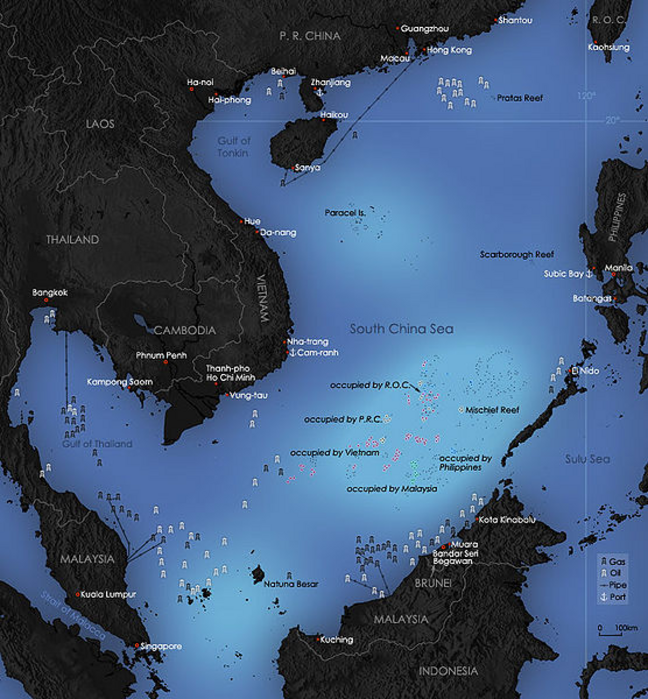

|

Contested islands in the South China Sea (Yeu Ninje 2006) |

This statement was understood as an overt attempt to multilateralize the issue. It was also, therefore, a direct challenge to China, which was asked once again to sacrifice its interests, specifically the advantages of its preferred negotiation strategy: fully leveraging its regional clout by negotiating bilaterally with its smaller Asian neighbors without the complication of placating the ASEAN group as a whole or coping with the intrusive presence of the United States.

The most recent event in China’s annus horribilus is the dust-up over the Diaoyutai/Senkaku Islands. In this case, the United States may have actually been trying to chart a middle way, but saw its policy blown out of the water by strident Japanese and Chinese nationalism.

A standoff between a Chinese fishing trawler and two Japanese Coast Guard vessels on September 7 off the Diaoyutai/Senkaku Islands led to the Japanese detention of Captain Zhan Qixiong and the provocative assertion that his case would be adjudicated under Japanese domestic law, rather than resolved through quiet diplomacy between Tokyo and Beijing.

|

Two Japanese Coast Guard boats pursue a Chinese trawler |

On any given day, hundreds of Chinese boats fish within Japan’s proclaimed Economic Exclusion Zone (EEZ); a few boats, including apparently Captain Zhan’s, don’t scruple to cross the line demarcating Japan’s territorial waters to fish close to the uninhabited islands.

News reports suggest that Zhan was something of a hothead. All it took was a Japanese over-reaction to make him a national hero. Japan’s hawkish minister Maehara Seiji can take a lion’s share of the credit or blame for blowing up the incident. The Asahi newspaper reported the timeline as follows: Maehara was still Minister of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism – in charge of the Coast Guard – at the time of the incident.

Immediately after the trawler collided with Japan Coast Guard vessels on Sept 7, Maehara called Coast Guard Commandant Suzuki Hisayasu and told him, “The captain of the Chinese fishing boat must be arrested.”

|

Coast Guard places Captain Zhang under arrest |

Maehara also called Chief Cabinet Secretary Sengoku Yoshito and told him, “It is better to persist resolutely against China.”

At first, China responded calmly.

Reflecting back on that time, a Chinese government source said, “By sticking to a calm response, China was trying to encourage Japan to release the captain on its own accord.”

But Maehara refused to back down.

He told close aides: “The prime minister’s office was hesitant so I had to make the decision to arrest the captain. There was no mistake in the handling of the matter.” [1]

Maehara was appointed foreign minister on September 21, days after his aggressive intervention in the incident.

It is rather ironic that Japan would demand diplomatic engagement of China in the South China Sea while simultaneously foreswearing it over the Daioyutai/Senkaku Islands. More important, the Diaoyutai/Senkaku story is not simply a matter of Japan standing up to the big Chinese bully.

By distance, geography, and history Taiwan has the best claim on the Diaoyutai Islands (which are a mere 170 km from Taiwan and separated from Okinawa by 410 km and a deep undersea trench), which Japan acquired during the course of imperial skullduggery involving the seizure of Okinawa in 1872.

With its display of undersea terrain, Google Earth provides an interesting perspective on these tiny islands just north of Taiwan, at 25°44’30.48” N 123°28’21.39”E, and separated from Japan’s Ryukyu Islands by the Okinawa Trough which, Wikipedia tells us, “marks the edge of the continental shelf of the East China Sea”.

Taipei responded to the incident by vociferously advancing its interest. President Ma Ying-jeou, who has played the Diaoyutai card throughout his entire political career, dispatched 12 Coast Guard vessels to shield a boat of Taiwanese activists that made a symbolic approach within 19 miles of the island on September 15.

The Japanese Coast Guard warned them off. Taiwanese media reported:

On several occasions the Kan En No. 99,” which means “Showing Grace” in the Chinese language, was just two meters from being rammed by Japan’s patrol ships. [2]

Taking into consideration the aggressiveness of the Japanese Coast Guard, it is easy to understand how frustration, fear, and anger might have combined with poor seamanship and bullheadedness to produce Captain Zhan’s collision. After Captain Zhan’s detention was extended, with indictment in a Japanese court apparently imminent, China moved aggressively both in the public and official spheres. Cancelling scheduled negotiations with Japan over undersea oil and gas deposits in the vicinity of Diaoyutai, it also canceled bilateral talks on airline flights and told Chinese travel agencies not to accept applications for tour groups to visit Japan – scuppering two initiatives that Maehara had championed as tourism minister.

China also allegedly cut off exports of rare earth oxides to Japan and the government detained four Japanese employees of Fujita in Shijiazhuang, capital of North China’s Hebei province, on charges of espionage-related activity, apparently in retaliation. Three of the men were subsequently released, and the fourth was returned after a period of detention that roughly matched Captain Zhan’s.

Judging from the Asahi article, Prime Minister Kan was not pleased that his term had begun with a major diplomatic dust-up courtesy of Maehara and his patron, Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) secretary general Okada Katsuya. Okada and Maehara are the two most powerful proponents of a strong US alliance within the DPJ, whose platform has emphasized accommodation with Japan’s Asian neighbors. As exchanges with China became more heated, Maehara recklessly upped the ante by pulling in the United States.

At the time of the crisis, it was well-known to Japan that the Obama administration had little interest in supporting Japanese assertions of sovereignty over the Senkaku Islands.

In August 2010, The Japan Times reported:

The Obama administration has decided not to state explicitly that the Senkaku Islands, which are under Japan’s control but claimed by China, are subject to the Japan-U.S. security treaty, in a shift from the position of George W. Bush, sources said Monday.

Although the U.S. government has not officially changed its stance that the Japan-U.S. pact applies to the uninhabited East China Sea islets, known in China as the Diaoyu isles, the shift from making a direct reference to them could become a source of concern for Tokyo as it addresses moves by Beijing, the sources said. Taiwan also claims the islets.

The administration of Barack Obama has already notified Japan of the change in policy, but Tokyo may have to take countermeasures in light of China’s increasing activities in the East China Sea, according to the sources. [3]

Whether Foreign Minister Maehara’s hard line one month later in September was provoked by the perceived need for Japan to stand up to China—or whether it was an affront calculated to force an unenthusiastic Obama administration to side with Japan on the Senkakus—remains to be determined.

After Maehara met with Secretary of State Hillary Clinton in New York, AFP reported:

“According to the Japanese minister, Clinton said that the Senkakus … are subject to Article 5 of the bilateral security treaty, which authorizes the US to protect Japan in the event of an armed attack ‘in the territories under the administration of Japan’,” the report said. [4]

Whatever was said in private, publicly the State Department did not inject itself in the controversy by explicitly extending the US security umbrella over the Senkakus. According to the AFP report, State Department spokesperson Philip Crowley limited himself to the observation that the Senkaku issue was “complicated”.

It appears that Maehara abused the secretary of state’s confidence by making public her sensitive and probably strongly caveated assurances of US support for Japan, in order to secure U.S. military backing for Japan’s claim to Diaoyutai/Senkakus, and for his aggressive move in ordering the arrest and prosecution of the Chinese captain.

Hopeful overreach continued with the Japanese press reporting that Defense Secretary Robert Gates and Admiral Mike Mullen, chairman of the U.S. joint chiefs of staff, had, in the words of the Japanese public-service broadcaster NHK, “indicated that the US security agreement with Japan covers the Senkaku Islands.” [5]

“Indicated” is much too strong a word.

The actual transcript of the Department of Defense briefing was long on waffling and offered no explicit commitment:

Q Chinese Premier Wen in New York on Tuesday threatened action against Japan if it didn’t return the captain of the ship. I’m wondering, does the US security umbrella extend to the Senkakus – the Senkaku islands?

ADM MULLEN: I think we’re watching those – that tension very, very carefully, and certainly our commitment to the region remains. And, you know, we’re hopeful that the political and diplomatic efforts would reduce that tension specifically, and haven’t seen anything that would, I guess, raise the alarm levels higher than that. And obviously we’re very, very strongly in support of, you know, our ally in that region, Japan.

Q And second –

SEC GATES: And we’ll – and we would fulfill our alliance responsibilities. [6]

In follow-on questions at the September 24 press briefing, the US State Department cited remarks by Jeffrey Bader, chairman of the National Security Council that the dispute was a matter between China and Japan. [7]

Further awkward parsing was pre-empted as Prime Minister Kan cut the legs out from under Maehara and Okada in the best circular firing squad tradition of the hapless DPJ by agreeing to Zhan’s release. The two hawks are striving to disguise their embarrassment with escalating anti-Chinese bluster.

At a time that China was saying that the case of Captain Zhan was “basically over ” [8], Maehara told the Japanese media that China’s demand for an apology demonstrated its “undemocratic nature”. He also made the provocative statement that China might be preparing to violate an agreement with Japan not to drill unilaterally for oil and gas in contested portions of the East China Sea.

Despite Japan’s humiliating retreat from its initial aggressive posture, the U.S. nevertheless received a propaganda windfall. Any threat, real or imputed, that China will deploy its military, economic, and financial clout to advance its interests in the East and South China Seas, strengthens the desire of China’s neighbors for a closer US alliance, or so U.S. Asia strategists believe.

Doyle McManus, the Washington correspondent of the Los Angeles Times, delivered the conventional US wisdom:

Because of China’s truculence, US relations with Japan, Korea and Vietnam have almost never been better. [9]

Actually, the root cause of friction in East Asia in 2010 is the Obama administration’s determination to “return to Asia”, most evident in the planned series of U.S.-ROK and U.S.-Japan joint military exercises in China’s backyard, and the encouragement this has given to anxious nations to pursue confrontations with China they might otherwise avoid. Certainly this has emboldened Japan, Korea, and Vietnam to confront the Chinese dragon.

It was Japanese, not Chinese, truculence that dictated the decision made at the cabinet level to arrest and try Zhan after the collision near Diaoyutai/Senkaku. This comes at a time of Vietnamese efforts to engage the United States as a counterweight to China, particularly over the nagging question of the Hoang Sa/Paracel/Xisha Islands in the South China Seas, which China seized from South Vietnam after a bloody encounter in 1974.

The issue gained heightened visibility with the report that China “formally declared to the United States that the South China Sea is a core interest”, implying to Western observers that China regarded the fate of the uninhabited islands and their associated oil and gas deposits as an existential issue presumably worthy of the attention of the People’s Liberation Army. In keeping with the theme of dubious, thinly sourced news reports with a Japanese link, however, this news item derived, virtually in its entirety, from a brief report filed by Kyodo News Service’s Washington Bureau on July 3, that the Chinese had stated this position to James Steinberg and Jeffrey Bader when they were in Beijing in March 2010. [10]

The report is anonymously sourced from somebody who was apparently not directly involved in the meetings — it states that the Chinese position was “presumably” conveyed by State Councilor Dai Bingguo. It is also interesting that this scoop was leaked to a Japanese news office in Washington; none of the plugged-in American news organizations got the story at that time (the only apparent corroboration is a statement in a July 2010 story by John Pomfret that Dai Bingguo had made the South China Sea a core interest in representation to Hillary Clinton during a “tense exchange” in May; and, as far as can be seen, Steinberg and Bader have not been asked to confirm the report.

It would appear noteworthy that the Chinese saw fit to announce this position to the only party they are attempting to exclude from the South China Sea dispute, the United States, while not conveying it to Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia, Brunei, or Indonesia, the interlocutors with whom it is trying to impose a series of bilateral negotiations. The United States is now apparently happy to spread the “core interests” meme, at least in private conversations between U.S. government officials and American reporters, although its accuracy and context have yet to be made part of the public record.

China has never officially confirmed or denied the story. Within China, there is skepticism that the Chinese government made any statement claiming South China Sea core interest. [11] As far as the public record goes, China remains committed to freedom of navigation in the South China Sea, the Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea (a standstill agreement negotiated with ASEAN in 2002), and negotiated settlements over disputed islands. Yet the fact remains that such statements remain exclusively in the realm of US journalism.

It is possible, of course, that the phrase “core interest” came up in the context of the continual criss-crossing of the South China Sea by the two US Navy surveillance vessels Impeccable and Victory.

The US Navy exploits a loophole in the Law of the Sea Convention allowing free transit through a nation’s exclusive economic zone in order to monitor and map the area near China’s strategic submarine base on Hainan Island. As such, U.S. efforts to undercut China’s nuclear deterrent—and improve U.S. prospects of intercepting and destroying China’s southern submarine fleet in case of a confrontation over Taiwan—could be construed as a matter of China’s “core interest” that the Chinese government might want to raise with American diplomats.

In any case, as publicly defined by the United States, China’s “core interest” in the South China Sea is a matter of sandbars, not submarines, and this has prompted the U.S. to inject itself in the South China Sea disputes as the champion of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations members, especially Vietnam, against Chinese territorial overreach. The “core interest” story has been a public relations gold mine for the United States as China has watched in dismay and frustration as several ASEAN nations led by Vietnam and Singapore lined up with the United States to push for internationalizing the dispute. However, the welter of islets and rocks presents a nearly intractable problem even if all the concerned parties desire a friendly solution. Even in the unlikely event that the ASEAN countries were to maintain a united front against China with US encouragement, it is unlikely that China will surrender its claims in an adversarial venue.

Benign neglect—in PRC terms, a policy of postponing thorny territorial issues while negotiating joint development of resources in disputed areas—has served the South China Sea pretty well over the last three decades and would probably be the best way to handle the problem in the future. A universal commitment to free passage through the vital waterways of the archipelago – a principle already accepted by all parties to the myriad territorial, fishing, and undersea resource disputes – is probably worth the price of tacit acknowledgement of the less than ideal status quo.

U.S. pressure on China in the South China Sea was quickly joined by Japan. In July, Okada was already pressing the South China Sea issue at the ASEAN Regional Forum. In a deliberate echo of Clinton’s July 23 statement injecting the US “national interest” into the South China Sea matter, Okada involved Japan:

Foreign Minister Katsuya Okada on Tuesday expressed his concern over territorial disputes in the South China Sea mainly between China and Southeast Asian nations, saying the instability in the area could hamper Japan’s trade and pose a threat to regional peace. ‘‘The instability deriving from differing views on territorial issues between China and ASEAN nations could undermine peace in Asia,” Okada told a press conference. ‘‘We should get rid of such a destabilizing factor as soon as possible.’‘ [12]

Given the realities of the situation, the eagerness of the U.S. and Japan to work through the Western press to turn the South China Sea issue into a regional crisis is worth noting.

A September 22 Wall Street Journal piece, entitled “US, ASEAN to Push Back Against China,” offered what it sold as a privileged preview of the ASEAN-US joint statement blockbuster:

On Friday, Mr Obama and the Asean leaders will issue a joint statement in which Washington has proposed text reaffirming the importance of freedom of navigation in the South China Sea, according to the Associated Press.

It said the statement would oppose the “use or threat of force by any claimant attempting to enforce disputed claims in the South China Sea.”

The wording is significant – and provocative for China – because it mirrors that of a speech by US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton at another Asean meeting in Hanoi in July.

Japan’s NHK obtained a copy of the same draft (bear in mind that Japan was not party to the agreement and not the most likely conduit for a leak). [13] Headline writers throughout the world ran leads like “US backs ASEAN stand against use of force in Spratlys. ” [14]

However, the actual text of the joint statement [15] said nothing about disputes in the South China Sea. Apparently, the edifice of US-ASEAN solidarity was not strong enough to withstand a strong, disapproving shove administered publicly by China’s Foreign Ministry on September 21 and undoubtedly through numerous private channels.

Having missed the boat on the joint announcement, the Wall Street Journal compounded its problems in an untimely encomium celebrating collective Japanese and ASEAN backbone vis-à-vis China:

Japan – the main US ally in the region – is leading the way in confronting China, taking an unusually firm line in a dispute over a collision between a Chinese fishing trawler and two Japanese Coast Guard ships near disputed islands in the East China Sea two weeks ago.

Evidence of the backlash – and its effect on China – is apparent in the current dispute between Beijing and Tokyo over the ship collision near the disputed islands called Diaoyu in China and Senkaku in Japan. Japan has released the trawler and the 14 crew, but continues to detain the ship’s captain.

China has summoned Japan’s ambassador six times and suspended high-level government exchanges. Mr Wen, China’s premier, personally demanded the captain’s release on Tuesday. Yet Tokyo has stood firm, apparently gambling that Beijing doesn’t want to damage commercial relations or provoke the kind of anti-Japanese violence that almost spiraled out of control during a similar row in 2005.

“Clinton’s stand in Hanoi may have contributed to Japan’s demonstration of more backbone than most of us give it credit for having in its current territorial confrontation with China,” said Mark Borthwick, director of the United States Asia Pacific Council at the East-West Center in Washington.

Four days later, Japan folded and returned Captain Zhan.

The unambiguous victory for China makes it hard to give credence to assertions that China’s foreign policy is out of control and driven by weakness, arrogance, runaway PLA hotheads, or cadet Politburo members recklessly burnishing their nationalistic credentials in the run-up to China’s generational leadership change, due in 2012. Nevertheless, John Pomfret did his best to spin a clear-cut diplomatic victory for Beijing as evidence of China’s foreign policy dysfunction and Japanese determination:

The increasingly bitter dispute between China and Japan over a small group of islands in the Pacific is heightening concerns in capitals across the globe over who controls China’s foreign policy.

A new generation of officials in the military, key government ministries and state-owned companies has begun to define how China deals with the rest of the world. Emboldened by China’s economic expansion, these officials are taking advantage of a weakened leadership at the top of the Communist Party to assert their interests in ways that would have been impossible even a decade ago.

It used to be that Chinese officials complained about the Byzantine decision-making process in the United States. Today, from Washington to Tokyo, the talk is about how difficult it is to contend with the explosion of special interests shaping China’s worldview. [16]

The fine lines between spin, self-delusion, and lazy disregard for geopolitical realities seem to be blurring, at least in the foreign affairs quadrant of the Western media.

USA Today pitched in, graciously ignoring Maehara’s role in intentionally escalating the confrontation, with a story under the headline, “China’s Aggressive Posture Stuns Japan, Experts”. [17] McClatchy, at least, indulged in honest sour grapes resentment: “Is a rising China getting too big for its britches?” [18]

The simplest explanation of China’s response was that China’s elites and public were largely united in their anger at Japan’s deliberate high-handedness over the issue of Captain Zhan and fishing rights in the vicinity of Diaoyutai; and the Chinese leadership recognized that any sign of weakness on Diaoyutai might encourage Vietnamese moves on the Paracels with U.S. and Japanese backing.

In Japan, the DPJ government, attempting to deal with the political fallout stemming from its retreat, continues to emphasize its absolute sovereignty over the islands and is reportedly mulling the stationing of a permanent garrison “near” Diaoyutai/Senkaku, presumably on Ishigaki Island, about one hundred miles from Diaoyutai, the nearest major inhabited island and the place where Captain Zhan was detained. [19]

At the September 29 press conference of China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan was called on to “adopt concrete actions to eliminate the negative effect on China-Japan relations brought by the incident and make practical efforts to mend bilateral relations.” (20) It is not clear what practical efforts China expects, or what Japan can be realistically expected to do in order to reassure Beijing that Tokyo is no longer interested in filling the role of one of America’s front-line assets on China’s borders.

Asia Times reported in early October that China, which sees no sign that Japan genuinely regrets inflaming the Diaoyutai/Senkaku situation, indicated at an ASEAN get-together in Hanoi that it is not quite ready to consider the issue resolved after all:

Chinese Defense Minister Liang Guanglie’s decision to lecture Japan’s Defense Minister Kitazawa Toshimi about how the incident near the disputed Diaoyu Islands between the Chinese fishing trawler and the Japanese Coast Guard demonstrated that Japan still does a poor job of handling sensitive issues affecting both countries, and is proof of a lasting chill. Liang wanted to remind Japan that Japan needs to resolve these and other matters in a way that ensures that China’s approval will be forthcoming…. This lecture was taking place just as China was issuing a terse announcement about its new maritime enforcement policies. Sun Zhihui, director of the State Oceanic Administration revealed that China intends “to strengthen patrols and supervision in order to protect the country’s maritime rights and interests”.

At the same time, Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao at a meeting in Brussels informed Japanese Prime Minister Kan Naoto that China had no plans to relinquish its claim to the Diaoyu Islands (called Senkaku by Japan) which the Chinese have always depicted as “an inherent part of the Chinese territory”.

“The Diaoyu Islands have been Chinese territory since ancient times,” Wen told Kan. [20]

At the same meeting, China rather slyly implied to the United States that its beef was with Tokyo, not Washington (and perhaps rewarded the Obama administration for its equivocal support of Maehara on the issue of Senkaku sovereignty).

The PRC extended to Defense Secretary Gates a longed-for invitation to visit Beijing and printed a picture in state media of Gates and Liang solemnly clasping hands in Hanoi under the heading Gates to visit China, defense ties normalize. [22]

Recently, Beijing has been ramping up the rhetoric on the Diaoyutai/Senkaku Islands, seemingly in order to highlight Tokyo’s discomfiture and sense of abandonment on the issue—“beating a dog in the water”, in Chinese parlance.

Japan has responded in kind. Geopolitical considerations aside, both sides see domestic political advantage in escalating the war of words.

Chinese nationalist hotheads were given relatively free reign to stage abusive, anti-Japanese demonstrations in several cities on October 16.

Foreign Minister Maehara responded by calling China’s reaction “extremely hysterical”; China’s Foreign Ministry, not to be outdone, stated that it was “shocked” at Maehara’s statement.

Former Prime Minister Abe emerged from obscurity to toss Hitler into the mix, accusing China of yearning for “Lebensraum” (for some reason, he decided not to run with a more apt World War II analogy and accuse China of harboring ambitions to establish a Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere). [23]

It appears that the Diaoyutai/Senkaku Islands will remain a low-level and—at least to hardliners in China, Japan, and the U.S.– not completely unwelcome irritant in China’s foreign affairs rather than the foundation for a meaningful diplomatic breakthrough in China’s relationship with its smaller and anxious neighbors.

There is a remarkable but virtually unnoted parallel between the Diaoyutai/Senkaku case and another confrontation during which the U.S. and its ally pushed, China pushed back, and the U.S. team folded: the Cheonan affair. Faced with U.S. and ROK efforts to use the sinking of the Cheonan as a justification for ostracizing the DPRK and making the fate of the peninsula a matter for the UN Security Council (and not the China-mediated Six Party Talks), China issued a high-level public endorsement of the Kim Jong Il regime and successfully pressured the Lee Myung-bak government to accept a return to the Six Party Talks.

The true lesson of the Diaoyutai/Senkaku crisis is that on regional matters China will ferociously oppose would-be US proxies like Japan—and South Korea and Vietnam–if they presume to advance US interests at Chinese expense. The other lesson that China would like its neighbors and enemies to extract from the situation is that the United States is happy to have its allies foment politically useful confrontations with China, but unwilling to alienate China by backing its proxies with determined diplomatic and military escalation when things get tough.

It appears that Beijing can and will deploy its preferred weapons— diplomatic pressure, economic coercion, legal jeopardy for foreign nationals and their interests —with far more speed and determination than the US and its allies can bring to bear despite their overwhelming military superiority. The United States and its Asian partners have done a good job of irritating China and provoking a dangerous crisis; they have yet to prove they can do as good a job of dealing with the consequences.

Peter Lee is the moving force behind the Asian affairs website China Matters which provides continuing critical updates on China and Asia-Pacific policies. His work frequently appears at Asia Times. He wrote this article for The Asia-Pacific Journal.

Recommended citation: Peter Lee, “High Stakes Gamble as Japan, China and the U.S. Spar in the East and South China Seas,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 43-1-10, October 25, 2010.

Notes

[1] Conditions were ripe for an escalating dispute with China, Asahi Shimbun, September 29, 2010.

[2] Convoy escorts Tiaoyutai protest boat, China Post, September 15, 2010.

[3] U.S. Fudges Senkaku Security Pact Status, Japan Times, August 17, 2010.

[4]Clinton says disputed islands part of Japan-US pact: Maehara AFP, September 24, 2010.

[5] Gates: US security alliance covers the islands “administrated by Japan”, NHK, September 24, 2010.

[6] DOD News Briefing with Secretary Gates and Adm Mullen from the Pentagon, US Department of Defense, September 23, 2010.

[7] State Dept, Daily Press Briefing, US Department of State, September 24, 2010.

[8] Chinese official says dispute with Japan mostly over with’, Mainichi Daily News, September 29, 2010.

[9] Doyle McManus: China tests the military waters and stirs up apprehension, Minneapolis Star Tribune, September 28, 2010.

[10] On one occasion China clearly declared to high US officials that the South China Sea is China’s core interest 中国曾向美高官明确表示南海乃中国的核心利益Kyodo, July 3, 2010. Link

[11] Unwise to elevate “South China Sea” to be core interest? People’s Daily Online, August 27, 2010.

[12] Okada airs concern over territorial disputes in South China Sea Japan Today, July 27, 2010.

[13] Draft of “US-ASEAN joint statement” obtained by NHK, NHK, September 17, 2010.

[14] US backs ASEAN stand against use of force in Spratlys Philippine Daily Inquirer, September 20, 2010.

[15] Joint Statement of 2nd US-ASEAN Leaders Meeting, New Asia Republic, September 25, 2010.

[16] China “concerned” possible US-ASEAN statement on S China Sea, Xinhua, September 21, 16. Dispute with Japan highlights China’s foreign-policy power struggle, Washington Post, September 24, 2010.

[17] China’s aggressive posture stuns Japan, experts, USA Today, September 28.

[18] Is a rising China getting too big for its britches? McClatchy Newspapers, September 24, 2010.

[19] Japan considers troop deployment near disputed islands. Australian News Network September 29, 2010. Link

[20] Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Jiang Yu’s Regular Press Conference on September 28, 2010.

[21] China stares past Gates in the Pacific, Asia Times October 14, 2010.

[22] Gates to visit China, defense ties normalize.

[23] China allows rowdy anti-Japanese protests, AP October 18, 2010.