The Epistemology of Torture: 24 and Japanese Proletarian Literature

By Heather Bowen-Struyk

“I absolutely do not believe that the show is, in any sense, torture porn. This is something we talk about a lot. Torture is of no interest to us as torture, and we’re not anxious to show it, nor do we want to watch it.” (Michael Loceff, writer for 24)

In the U.S., torture has become a spectacle to be consumed: from media representations of the abuses of Abu Ghraib, Guantánamo, and statements by Vice President Dick Cheney defending the rights of the U.S. to practice torture for intelligence-gathering, to high-profile representations of torture in American popular culture like Fox television’s 24 and the recent box-office hit Hostel (2006). One critic remarked, “Maybe it’s pure coincidence that Hostel became a hit after two years of headlines about Abu Ghraib and the rise of anti-Americanism in Europe.” [1] Then again, as the haunting coincidence suggests, maybe not. “Asked if he’s got any theories about why sadism is in vogue, [horror film director Wes Craven] laughs and says, ‘Because we’re living in a horror show. The post-9/11 period, all politics aside, has been extremely difficult for the average American.’” [2] Referring to the proliferation of horror shows featuring torture by that phenomenon’s nickname, “torture porn,” one critic writes: “As a horror maven who long ago made peace, for better and worse, with the genre’s inherent sadism, I’m baffled by how far this new stuff goes—and by why America seems so nuts these days about torture.” [3]

I am also baffled, but moreover alarmed. Despite being an American living through these times, learning about Abu Ghraib and casually watching 24 for entertainment, I cannot suppress a feeling of culture shock, as though the strange convergence is the result of someone else’s cultural logic. As a researcher, I work on the proletarian arts movement in Japan, a movement that the cold war has anesthetized so that it appears most relevant as a historical artifact. And it is relevant as a historical artifact, because, to begin, every major Japanese writer and intellectual writing in the late 1920s and early 1930s engaged the issues raised by proletarian literature. Indeed, the far-reaching consequences of massive inflation and mass unemployment in the midst of the development of a consumer culture on a new scale were apparent to everyone—right, left and center. As throughout the developing world in the first half of the 20th century, intellectuals, activists, workers and artists in Japan formed strategic alliances to address these crises. Of course, now that the cold war has thawed and the binary logic of two worlds has been replaced by a single superpower pursuing a militarist-neoliberal agenda, we might find that the most pressing questions of proletarian literature are still relevant today.

What do proletarian literature and the context of the 1930s in Japan have to do with American popular culture and torture? Torture plays an important role in Japanese proletarian literature, and the contrast between that role and the current role that torture is playing in American popular culture propels me to write. Torture in proletarian literature is repressive, in the interest of the state at the expense of the people, and wrong.

Torture frames the proletarian movement—from Kobayashi Takiji’s story of the infamous round-up and torture of suspected leftists on March 15, 1928, to the death of Kobayashi himself by torture while under interrogation on February 20, 1933.

|

Figure 1: Mourners gathered around Kobayashi |

The community of mourners who gathered around his body risked not only arrest but torture. It is said that interrogators would taunt their prisoners with the threat of doing them in like Kobayashi. The image of mourners gathered around Kobayashi Takiji’s body has become iconic, a testament to the brutality suffered by those who participated in left-wing activities and the commitment of the community who gathered to mourn despite the risks. [4]

Among Americans, I am not alone in my alarm at the revelations of American torture in the so-called War on Terror. Nor am I alone in thinking that our willingness to allow torture is not a result of their moral failures. Abu Ghraib, once site of human rights abuses under Saddam Hussein, will be remembered for American human rights abuses. Amnesty International reports: “While the government continues to try to claim that the abuse of detainees in U.S. custody was mainly due to a few ‘aberrant’ soldiers, there is clear evidence to the contrary. Most of the torture and ill-treatment stemmed directly from officially sanctioned procedures and policies—including interrogation techniques approved by Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld,” said Javier Zuniga, Amnesty International’s Americas Programme Director. [5] Alfred McCoy writes, “At the deepest level, the abuse at Abu Ghraib, Guantánamo, and Kabul are manifestations of a long history of a distinctive U.S. covert-warfare doctrine developed since World War II, in which psychological torture has emerged as a central if clandestine facet of American foreign policy.” [6] There is substantial public opinion in the U.S. against the use of torture, which takes the form of websites, organizations, academic and mainstream writing, journalism and activism. At the same time, the discussion of torture in the U.S. is characterized by moral ambiguity.

This public moral ambiguity regarding torture makes a spectacular appearance in popular culture. In Hostel, two jackass young American men behaving badly in Europe are lured by the promise of beautiful, easy women into becoming terminal prisoners in an enterprising new industry, a place where the well-off can pay for the pleasure of torturing a victim to death with impunity. Hostel offers up the horrifying/titillating experience of watching someone torture for fun. The moral of this film is deeply ambiguous: the better of the two young men dies horribly, and his jackass friend manages to escape and carry out revenge, but the revenge sequence seems tacked-on and anti-climactic in contrast to the earlier torture scenes. ABC’s popular drama Lost also engages the torture question with a deep moral ambiguity. One of the characters marooned on the island, Sayid, was an Iraqi who was captured by Americans during the first invasion of Iraq and forced to learn to torture his peers for U.S. intelligence-gathering. On the show, he is a decent man who knows his own heart of darkness: his past experience with torture and his willingness to use it in the present when circumstances call for it are apparently not enough to make him a villain. This character—a sympathetic Iraqi who tortured for Saddam Hussein, then was taught to torture by the U.S.—symbolizes popular culture’s acknowledgment, unease and, finally, acceptance of unethical U.S. intelligence-gathering techniques.

The impact that the “pain of others” will have, as Susan Sontag has discussed, is notoriously difficult to predict: “No ‘we’ should be taken for granted when the subject is looking at other people’s pain.” [7] Nevertheless, I find it satisfying to identify a clear moral message regarding torture in proletarian literature. And I wonder whether such nostalgia could be a progressive force to help us reconceive our present as one in which those who allow torture are complicit with a moral outrage.

9/11, 9/18 and “Info-tainment”

The war fever engendered by 9/11 created a public climate with considerable tolerance for the pain of others. The war fever generated by 9/11 resonates with the war fever generated by the Manchurian Incident on September 18, 1931. On 9/18, an attack on the Japanese-leased railway in Manchuria (Northeast China) was staged by agents of the Japanese Kwantung Army to provide a pretext for them to invade and occupy the region. Manchuria was renamed Manchukuo and a puppet-state was established in March 1932. When the news of the Manchurian Incident first broke in Japan, Louise Young writes, “early editions throughout the country reported that [Chinese warlord] Zhang Xueliang’s soldiers had attacked the Japanese Army. On the front page of the nation’s leading daily, the Osaka Asahi, Japanese read that ‘in an act of outrageous violence [boryoku], Chinese soldiers blew up a section of Mantetsu track located to the northwest of Beitaying [Military Base] and attacked our railway guards.’” [8] As the invasion and consequent occupation of Manchuria unfolded over the next six months, the press and radio competed with each other for audiences by means of spectacular war coverage.

War fever generated by the 9/18 Manchurian Incident was not restricted to news outlets. Young describes the cultural production of “info-tainment,” as consumer culture cashed in on the “popular conviction that what audiences were viewing was live history” in songs, theater, film and fiction: “Rendering the brutality of war in the comforting conventions of melodrama and popular song, the entertainment industry obscured the realities of military aggression even as it purported to be informing audiences about the national crisis.” [9]

9/11 likewise sparked war fever in American popular culture. Toby Keith’s 2002 hit “Courtesy of the Red, White and Blue (An Angry American)” gave American country music listeners a rallying war cry:

Now this nation that I love

Has fallen under attack

A mighty sucker punch came flyin’ in

From somewhere in the back

Soon as we could see clearly

Through our big black eye

Man, we lit up your world

Like the 4th of July

. . .

‘Cause we’ll put a boot in your ass

It’s the American way [10]

Toby Keith’s album Unleashed was propelled by this angry hit to triple-platinum status (selling over 3,000,000 copies). Keith’s lyrics skillfully mimic the rhetoric of the “War on Terror” with its blurring of the enemy. At the time that Keith wrote this song and was performing it for the military (after refusing, at first, to record and release it), the U.S. had launched an invasion of Afghanistan in search of Al-Qaeda.

Almost immediately, however, the invasion of Iraq was prepared through the skillful innuendo that Iraq was responsible for 9/11—notice that the “sucker punch” came from somewhere that seems to rhyme with “Iraq”: “under attack,” “in the back,” and “black eye.” [11] And the reference to lighting up “your world / Like the 4th of July” seems to capture the popular embrace of the nickname for the invasion of Iraq, “Shock and Awe.” Keith followed up this album with his 2003 quadruple platinum album Shock’N Y’all.

Historians of Japan have reflected on the similarities between 9/11 and 9/18: a terrorist attack ignited nationalist furor, enabling public sentiment to support a military invasion that resulted in a foreign occupation with a consumer culture war fever boom in support of the grand possibilities of exporting civilization. Just as the United Nations refused to condone the Iraq invasion, the League of Nations refused to condone Japan’s invasion of Manchuria, so Japan withdrew from the League in March 1932. Progressive historians of Japan see the Manchurian Incident as the beginning of the Pacific War or the Fifteen Years’ War, a war that escalated into an immensely costly total war by the early 1940s and devastating defeat in 1945.

Japanese Proletarian Literature and Torture

The contemporary torture debate in the U.S. focuses on how to define torture and how to decide when, if at all, it is acceptable. By contrast, the representation of torture in Japanese proletarian literature is consistent: it is a repressive instrument of the state to intimidate, coerce and extract recantations. Torture has an unambiguous moral meaning, as in this line from Kobayashi Takiji’s “March 15, 1928”: “When Watari was being tortured, he felt a fiery resistance awaken in him towards the indescribably despicable capitalists. He realized that torture is the concrete manifestation of the repression and exploitation of the proletarian class by the capitalists.” [12]

As the proletarian literature movement in Japan swelled in numbers and enthusiasm, the state responded with repression. Between 1928 and 1941, nearly 66,000 arrests of suspected leftists were made. These mass arrests began with the infamous round-up on March 15, 1928, and continued to increase until 1933. Elise Tipton writes, “References to the [March 15] mass arrest in popular songs suggest its widespread impact on the public mind.” [13]

Kobayashi Takiji (1903–1933) achieved literary fame with his account of the mass arrests. “March 15, 1928” tells the story of members of a labor union arrested in the northern port city of Otaru, Hokkaido. The story was banned immediately, despite having been published in a highly censored form. The story climaxes with the gruesome and graphically described torture of a heroic organizer named Watari. He endures being stripped and beaten for thirty minutes with a bamboo sword before losing consciousness the first time. The narrator interjects, with sarcasm: “But, of course, now there was Article 135 of the criminal code. ‘The principle of considerate and decent treatment of suspects should result in opportunities for them to speak the truth.’” [15] The second time Watari loses consciousness it is because he is strangled. The third time, he is hung from the ceiling and pierced with thick needles.

Watari is unfailingly heroic in the face of brutalization, and the violence he suffers sanctifies his superiority. When his tormentors taunt him, he responds in kind. The police fail to extract a confession:

In the end, the police punched him and kicked him recklessly, with shoes that had metal nailed into their soles. It continued without stopping for an hour. Watari’s body rolled around loosely like a sack of potatoes. His face was like “Oiwa,” [a literary figure]. Then, after three hours of continuous torture, Watari was thrown back into his cell like so much pig’s offal. He lay like that until the next morning, still, groaning. [16]

Not all those who were arrested and interrogated managed to endure it so heroically. Some suffered serious injuries as a result of abuse or neglect that led to deaths. Nakano Shigeharu’s “The Winds of Early Spring” (Harusaki no kaze, 1928) tells the story of a baby—caught up in the mass arrests—who dies when denied proper medical attention. Nakano’s “House in the Village” (Mura no ie, 1935) describes the psychological torment that forced him to officially renounce the movement, and Murayama Tomoyoshi’s “White Nights” (Byakuya, 1934) similarly details the anxiety of having to live with oneself after having failed to be heroic.

The context of imminent arrest and possible abuse or torture for those active in left-wing activities in the 1930s is recorded in several works of reportage by Miyamoto [Chujo] Yuriko (1899–1951), feminist and proletarian writer. She described her first (of ten) incarcerations in two mid-length works of reportage: “Spring 1932” (1932 no haru, 1932/1933) and “Moment by Moment” (Kokkoku, 1951). [17] These works are redolent of her characteristic optimism in the midst of a debilitating mass arrest of those associated with the Proletarian Writer’s League (known as the Sakka Domei or NALP) in April 1932. Things looked grim for proletarian writers in spring 1932 with the formal establishment of Manchukuo in March, and a round of mass arrests in April.

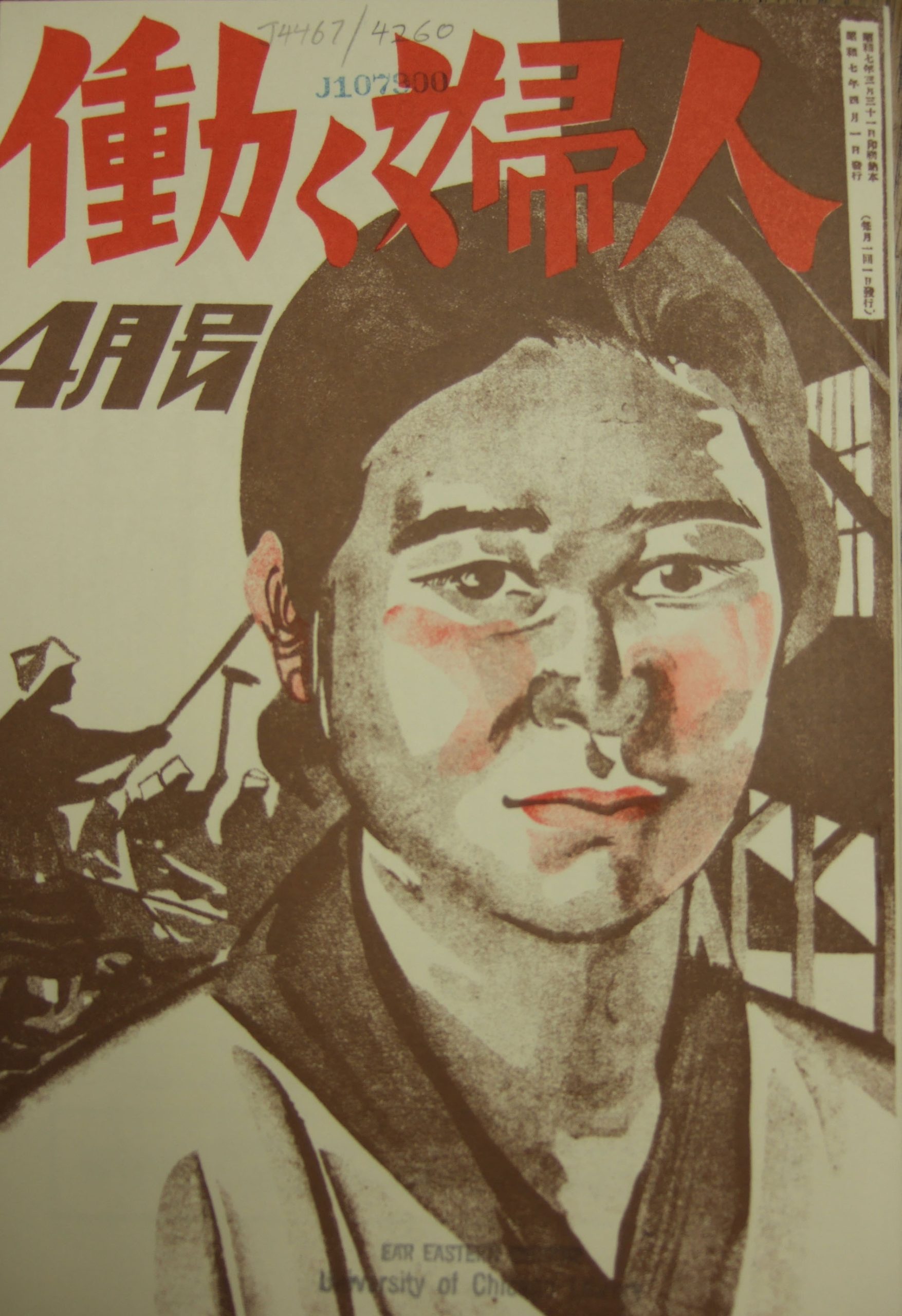

Miyamoto Yuriko was the editor of Working Woman, one of the populist journals published by the proletarian organization KOPF. [18] Like her peers, Yuriko argued that the proletariat was being exploited by capitalism (“Could capitalist production continue on even one day without the proletariat?” [19]), she opposed the invasion of Manchuria, suggesting that it would escalate into World War II (p. 4), and she insisted that “the only class capable of producing truly creative women writers today” was the working and farming class (p. 7). In April 1932, she was arrested with dozens of others. [20] Her husband escaped temporarily to the underground while she spent 80 days in jail. He was later arrested and remained in prison until postwar political amnesty led to his release.

The first half of “Spring 1932” documents Yuriko’s activities in March and early April 1932. She travels to semi-rural Shimosuwa to participate in a newly established literary circle for factory workers, and she is excited to find that the journal she edits, Working Woman, is actually read by them (p. 5–6). Throughout the course of the first half of the work, Yuriko continues to learn of comrades who have been arrested: Hirada Ryoei, Nomura Jiro, Kubokawa Tsurujiro, Terashima Kazuo, and others (p. 4). She learns about the arrests by reading about them in the paper and by word of mouth. The repetition of arrests is an ominous leitmotif, both suggesting the mass scale of arrests and setting us up for her arrest.

Yuriko’s arrest on April 7, 1932, occurs about halfway through “Spring 1932.” She returns home to find policemen have made themselves at home, and they take her to jail. Yuriko’s narrative builds slowly, conveying convincingly what it is like to be thrust into demoralizing living conditions indefinitely: she describes her cell and its squalor, the substandard food, and the interrogations. She is repeatedly questioned about her relationship to the illegal Japanese Communist Party, and it is suggested that even members of legal left-wing organizations will be treated like criminals. She is repeatedly questioned about her work for Working Woman, especially the April 1932 edition. (See figure 2.)

|

Figure 2: Cover of Working Women |

One of the most harrowing scenes occurs in the second piece, “Moment by Moment,” as she relates her efforts to get the warden to give poet and activist Konno Dairiki the medical attention he needs after having been battered in the head during an interrogation. Eguchi Kan writes that the special higher police acquiesced because they did not want him to die in prison. [21] However, Konno Dairiki did die due to complications arising from the middle-ear infection he contracted after the beating. Yuriko’s stories are rich with detail about the climate of torture and fear that proletarian writers experienced in this period. Most harrowing is the appearance of Nakagawa Shigeo as one of her interrogators; Nakagawa is the man who tortured Kobayashi Takiji to death. [22]

In Thought Control in Prewar Japan, Richard Mitchell commends the Special Higher Police for having resorted to violence less than their peers in fascist countries, and suggests that reports of torture by leftists were probably exaggerated. As evidence, he suggests we need to evaluate not only the testimonies of those who were imprisoned, but also the official documents dictating proper treatment of prisoners to find a more balanced approach. This “balanced” approach dismisses testimonies by prisoners. Written in the context of cold war paranoia and CIA experiments in mind control (described so well by Alfred McCoy), Mitchell’s approach emphasizes the efficacy of nonviolent methods to interrogate and rehabilitate left-wing “thought criminals,” ignoring the abundant testimony and documentary record of injuries and deaths. [23]

In her study of the Special Higher Police [Tokko], responsible for much of the brutality, Elise Tipton confirms that torture was a common practice:

Defenders and critics of the police, especially the Tokk, disagree over the existence and extent of police brutality and its “trampling of human rights.” Critics contend that the Tokko carried out organized torture and terror, making it comparable to the Gestapo or GPU (State Political Administration). Defenders, such as former Tokko officials, protest that use of torture was the exceptional act of individuals, not the policy of Tokko leaders. The actual extent of police brutality lies somewhere between these two extremes, but certainly there are too many recorded cases of torture to be able to deny its frequent use by Tokko officials. [24]

It is not surprising that the former Tokko officials would deny torture as a common practice despite evidence and testimonies to the contrary.

24: The Moral Ambiguity of Torture

In proletarian literature, torture is a clear sign of repression. In contrast, torture has a different logic on popular Fox TV drama 24. Richard Kim summarizes the first three seasons: “Along the way [protagonist Jack Bauer] shoots kneecaps, breaks fingers, kills his boss, chops off his partner’s hand, electroshocks enemies, withholds heart medication, threatens ‘Russian gulag towel torture’ and fakes the murder of a suspect’s child on live video feed.” [25] Torture is used for intelligence-gathering in all five seasons, with a spectacular diversity and frequency. Matt Feeney writes, “On 24, torture is less an unfortunate last resort than an epistemology. Whenever an urgent or sticky question of fact arises, someone—bad guy or good guy, terrorist or counter-terror agent; it doesn’t matter—automatically sparks up the electrodes or starts filling syringes with seizure juice.” [26]

|

|

Season one of 24 began just two months after 9/11 and season five finished in May 2006, with another season planned as well as a movie. These five seasons span the so-called War on Terror, engaging major themes of the war such as radical Islamic terrorists, splinter cells in the U.S., nuclear threats, fabricated evidence, torture and the question of complicity between the government and big business. In fact, the premiere broadcast was delayed and the pilot episode modified in order to downplay the plot elements that were too close to 9/11: a plane being blown up and a terrorist threat on the U.S. The writers were, at the time of 9/11, already working on the fourth and fifth episodes, so the uncanny similarities must be coincidence. [27] In addition, two seasons of 24 confront the fall-out from special operations gone bad in the now nearly forgotten U.S. invasion of the former Yugoslavia.

Each of the five seasons takes place in a fictional 24 hours with a digital clock periodically ticking off the seconds to remind the viewer that this is all supposedly taking place in real time. Each season, a fictional Counter-Terrorist Unit (CTU) in Los Angeles works around the clock to prevent an imminent terrorist threat on the United States. They are always successful but not without casualties. In season one, a Serbian father and son seek retaliation for a botched special operation that killed innocent family members two years earlier; in season two, a Middle-Eastern terrorist sect plans to detonate a nuclear bomb in the U.S., and a collusion between big business and government not only allows the bomb into the U.S., but tries to roll the incident into a war by producing fabricated evidence that would implicate three Middle-Eastern countries in the attack; in season three, a deadly virus makes its way into the hands of a disgruntled former U.S. military man (who was mistakenly left behind in the botched Serbian mission and, as a consequence of enduring insufferable torture, now seeks vengeance on the U.S.); in season four, a radical Islamic splinter cell plots to capture and launch a U.S. nuclear missile; in season five, an anti-terrorist agreement is signed by Russian and U.S. presidents while military-grade nerve gas finds its way into the hands of dissident Russians with the complicity of the president of the United States.

Through it all, protagonist Jack Bauer is a renegade agent who can get results when no one else can because he is willing to do what must be done, no matter how it might “shock the conscience.” Not all torture in 24 is above the law, apparently, as there is an official interrogation room (with a one-way mirror and syringe-wielding technician) and a protocol for using this room to get information from suspects. This clinical torture is in contrast to the instances when Jack tortures, as he usually does so in clear violation of CTU protocol. This is, I argue, a necessary part of the dynamic of moral ambiguity created by the show’s plotlines: viewers are carried along, simultaneously relieved that his actions are illegal AND that Jack is willing to do it to protect “us.”

Debate on torture follows the logic of 24 (or vice versa). Vice President Dick Cheney explained President Bush’s resistance to Senator John McCain’s Anti-Torture Amendment thus: “And the debate is over the extent to which we are going to have legislation that restricts or limits that capability [to have effective interrogation]. Now, as I say, we’ve reached a compromise. The president signed on with the McCain amendment. We never had any problem with the McCain amendment. We had problems with trying to extend it as far as he did.” [28] Cheney’s point: for purposes of intelligence gathering, the anti-torture laws (both international law and U.S. law) should not apply. And if anyone has any qualms, he immediately invokes 9/11:

Now, you can get into a debate about what shocks the conscience and what is cruel and inhuman. And to some extent, I suppose, that’s in the eye of the beholder. But I believe, and we think it’s important to remember, that we are in a war against a group of individuals and terrorist organizations that did, in fact, slaughter 3,000 innocent Americans on 9/11, that it’s important for us to be able to have effective interrogation of these people when we capture them. [29]

In response to Terry Moran’s question—“Should American interrogators be staging mock executions [and] waterboarding prisoners? Is that cruel?”—Cheney declines to comment on specifics, and quickly shifts the discussion back to 9/11:

Cheney: I can say that we, in fact, are consistent with the commitments of the United States that we don’t engage in torture. And we don’t.

Moran: Are you troubled at all that more than 100 people in U.S. custody have died—26 of them now being investigated as criminal homicides—people beaten to death, suffocated to death, died of hypothermia in U.S. custody?

Cheney: No. I won’t accept your numbers, Terry. But I guess one of the things I’m concerned about is that as we get farther and farther away from 9/11, and there have been no further attacks against the U.S., there seems to be less and less concern about doing what’s necessary in order to defend the country. [30]

Cheney’s assertion—“we don’t engage in torture”—begs to be analyzed: is he saying that the CIA farms out torture? That CIA interrogation methods fall short of legal definitions of torture? That it is not torture if it is not on U.S. territory? That it is not torture if conducted by U.S. authorities? Moran’s attempt to render the effects of torture concretely in the form of the deaths being considered possible homicides is evaded by Cheney by the swift insistence that people need to remember 9/11 so that they will allow the sorts of things—implicitly, the possible homicides that Moran has just evoked—“in order to defend the country.” Vice President Cheney’s logic—simultaneously assuring us that “we do not torture” while reminding us “about doing what’s necessary in order to defend the country”—is the logic that is played out every week on 24 as Jack Bauer routinely does “what’s necessary in order to defend the country.” Just as Mark Bowden writes that “coercive interrogation ‘should be banned but also quietly practiced,’” [31] 24 puts viewers in the position of being relieved, indeed grateful, that Jack Bauer is willing to break the law and torture. After all, Jack does avert a nuclear holocaust on several occasions.

In the logic of the show, his efficacy (and the drama) depends on his prisoner (and the viewer) never really knowing what he is capable of doing. When interrogating the woman who had killed his pregnant wife at the end of the previous season, for example, Jack explains to his supervisor that she needs to believe that he is above the law in order to get results. [Day 2: 1:09–1:18] The idea is that because this woman is a trained spy, she can resist ordinary interrogation methods; therefore, the only way to get results from her is to go off the map of what she expects. Jack Bauer’s assertion echoes that of real-life torture advocates. For example, Heather MacDonald writes: “Since the Abu Ghraib scandal broke, the military has made public nearly every record of its internal interrogation debates, providing al Qaeda analysts with an encyclopedia of U.S. methods and constraints. Those constraints make perfectly clear that the interrogator is not in control. ‘In reassuring the world about our limits, we have destroyed our biggest asset: detainee doubt,’ a senior Pentagon intelligence official laments.” [32]

Torture in 24 is exploited for its dramatic appeal in addition to simply moving the plot along with the next piece of information. For example, occasionally there are—even within the logic of the show—lamentable instances when the wrong people get tortured. In season four, for example, the son of the Secretary of Defense (who is both Jack Bauer’s boss’s son and his girlfriend’s brother) withstands torture rather than admit to his righteous father that he is gay and spent the night with someone who turns out to have been involved in the plan to kidnap his father. [Day 4: 9:00 a.m.–10:00 a.m., first aired 1/10/2005] It is not clear what part of that information was worth protecting.

In season four, Jack improvises electrical shock torture by exposing the wires in a lamp that is plugged in; he does this in order to interrogate his girlfriend’s estranged husband who is “not cooperating.” Jack explains to his girlfriend, “Right now Paul is a prime suspect, and he’s not cooperating. I don’t have time to do this any other way.” Jack douses Paul with water, while holding the exposed wires, and Paul says, “You’re bluffing.” Jack responds by electrocuting him. [Day 4: 5:00–6:00] (See figure 4.) A couple of hours later, Paul not only forgives Jack, but he helps Jack track down the information he needs and then takes a bullet for him.

|

Still from 24, Season 4: 5:00–6:00 p.m.; |

In season five, Jack’s girlfriend Audrey is subjected to the beginning of a torture-driven interrogation by their own people when a terrorist names her as a source. Jack stops the interrogation by going in and threatening to torture her himself if she isn’t telling the truth. [Day 5: 9:00 p.m.–10:00 p.m., first aired 3/27/2006] As horrible as it seems to have Jack roughing up his girlfriend, it actually makes sense within the show because on the one hand, his lover in the first season turned out to be involved with the terrorists, and on the other hand, by roughing her up, he is able to assure himself and everyone else that she must really be innocent. Jack’s talent, which is just as mystical as a superhero’s special power, is roughing people up and getting them to tell the truth. Jack is tortured on a couple of occasions [for example, Day 2: 2:00 a.m.–3:00 a.m., first aired 4/15/2003], and season five ends with his capture and torture by Chinese seeking revenge for the accidental death of an ambassador in season four.

In fact, torturing is so much a part of protagonist Jack Bauer’s character that in an interrogation, he threatens his prisoner: “I’m done talking with you, you understand me? Now you read my file. First thing I’m gonna do is take out your right eye, then I’m a move over to your left, and then I’m gonna cut you, and I’m gonna keep cutting at you until I get the information that I need. Do you understand me??” [Day 5: 12:00–1:00] One tv.com viewer commented, “Ooo – a new method interrogation – threaten to poke the suspect’s eyes out to get him to talk – I LOVE Jack Bauer!!!!” [33]

An interview with one of the writers for 24, Michael Loceff, posted in January 2006, addresses the question of whether 24 is producing torture porn:

Slate: One of the places where 24 and the real world have intersected most powerfully is on the question of torture. On 24, torture is regularly used in interrogation. Some critics believe that 24 actually plays to our desire to witness torture, that it is, in some sense, “torture porn.” How do you make sense of and justify the role of torture in the show?

Loceff: I absolutely do not believe that the show is, in any sense, torture porn. This is something we talk about a lot. Torture is of no interest to us as torture, and we’re not anxious to show it, nor do we want to watch it. We don’t want to go to any level of great detail in depicting it, and there are many times when we will pull back from the original idea because it seems too much. I think its real use in the show, aside from its narrative function, is to create dramatic conflict, conflict not just between two people but within characters as well. If you look at any given torture scene in the show, you’ll find that there’s something in it that shows someone’s distaste or disgust. And Jack Bauer’s decision to torture people for information in the past has cost him, because it’s shown other people just exactly what he’s capable of. Jack himself is appalled by what he feels he has to do, but he’s also convinced he has to do it. That is a real dramatic conflict. [34]

Loceff defends the show from torture porn accusations by pointing out that the torture scenes are not necessarily graphic so much as they are dramatic. That is, it is not necessarily that the viewer wants to watch torture, but that Loceff thinks that the dilemma of whether or nor to torture has inherent dramatic appeal. In season five, Jack Bauer very nearly tortures the President of the United States. Like other scenarios that speak to a political unconscious, in this case the fictional President would have deserved it with the logic of the show because in this season he did, after all, enable terrorists to deploy weapons in the U.S. The drama is created—as 24 writer Loceff says—because the viewer really doesn’t know whether Jack Bauer will torture the President to get him to confess that he was responsible for the terrorists getting the weapons (and the death of an ex-President).

The problem is that exploiting the inherent drama of torture has the effect of putting the viewer in the position of allowing, moreover hoping that torture will save the day. And this desire that is produced in the viewer resonates with the arguments of torture advocates. The greatest fantasy of torture advocates—that it produces accurate information—is also played out repeatedly in 24. Not only does Jack Bauer manage to get the information in the nick of time, he manages to get accurate information. Richard Kim writes, “Jack’s above-the-law methods always work, but usually with only seconds to spare. If this is beginning to ring a bell, it’s because 24’s absurd plot and gimmicky premise indulge the ‘ticking bomb’ scenario so commonly invoked by apologists for real-life torture. When Harvard law professor Alan Dershowitz risibly proposed that judges ought to issue torture warrants in the ‘rare “ticking bomb” case’ (which, as even he admits, has never occurred in the United States), he might as well have been scripting 24’s next season.” [35]

Conclusion

The images from Abu Ghraib that shocked the American public have been dismissed by some as the sadistic actions of a few “bad apples,” but overwhelming evidence shows that torture is central to U.S. intelligence-gathering. Alfred McCoy writes, “these photos [from Abu Ghraib] are not, in fact, snapshots of simple sadism or a breakdown in military discipline. Rather, they show CIA torture methods that have metastasized like an undetected cancer inside the U.S. intelligence community over the past half century . . . Indeed, the photographs from Iraq illustrate standard interrogation practice inside the global gulag of secret CIA prisons that have operated, on executive authority, since the start of the war on terror.” [36]

American popular culture tends to treat torture like a complex issue with difficult choices that need to be made. Screenwriters use this inherent drama to great effect. Viewers are put in the position, oftentimes, of hoping that someone like Jack Bauer will use torture as a necessary evil in order to get the information to save innocent lives. Rehearsing this logic over and over must have a numbing effect on viewers, even those who know that torture is wrong.

No doubt, my nostalgia for Japanese proletarian literature and its unequivocal stance on torture overlooks—as nostalgia is prone to do—complexities and ambiguities. But nostalgia, with its desire for a time that is better than our present, is helpful to the degree that it helps us clarify what it is that we should improve about our present.

Heather Bowen-Struyk is the guest editor of the Fall 2006 positions: east asia cultures critique special edition, Proletarian Arts in East Asia: Quests for National, Gender, and Class Justice. Bowen-Struyk is currently working on a manuscript on gender and politics in Japanese proletarian literature. She wrote this article for Japan Focus. Posted on September 23, 2006.

Endnotes

[1] Devin Gordon, “Horror Show,” Newsweek (April 3, 2006), 61.

[2] Ibid., 61.

[3] David Edelstein, “Now Playing at Your Local Multiplex: Torture Porn—Why has America gone nuts for blood, guts, and sadism?” New York Movies (February 6, 2006)

(accessed June 1, 2006).

[4] See selections from memoirs by people who participated in the movement and gathered to mourn Kobayashi Takiji in the Kobayashi Takiji Collection (Kobayashi Takijisho, by the Proletarian Literature and Arts Research League (Puroretaria bungaku-geijutsu kenkyu renmei), (February 20, 1999) (accessed May 20, 2006).

[5] From “US: Government creating ‘climate of torture’” (May 3, 2006)

[6] Alfred W. McCoy, The Question of Torture: CIA Interrogation, from the Cold War to the War on Terror (Metropolitan Books, Henry Holt and Company: New York, 2006), p. 7.

[7] Susan Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others (Farrar, Straus and Giroux: New York, 2003), 7. The phrase “moral monsters” is hers: “Not to be pained by these pictures [of war destruction], not to recoil from them, not to strive to abolish what causes this havoc, this carnage—these, for Woolf, would be the reactions of a moral monster.” P. 8.

[8] Louise Young, Japan’s Total Empire: Manchuria and the Culture of Wartime Imperialism (University of California Press, 1998), 57–58.

[9] Ibid., 74.

[10] Toby Keith, Unleashed (2002). Lyrics from his official website: (accessed August 1, 2006).

[11] Compare Alan Jackson’s “Where were you when the world stopped turning?”: “I’m just a singer of simple songs / I’m not a real political man / I watch CNN but I’m not sure I could / Tell you the difference in Iraq and Iran.” Drive (2002). (accessed July 1, 2006).

[12] Kobayashi Takiji, “March 15, 1928,” translation is mine. Online Japanese version available at Shirakaba bungakukan, Takiji Laiburarii, This line is also cited in Norma Field’s essay on “March 15:” “’1928nen 3gatsu 15nichi’: Gomon kakumei nichijosei” ([“March 15, 1928”: Torture, revolution, and everydayness] in Gendai Shiso bukku gaido Kojiki kara Maruyama Masao made tokubetsu rinji zokan go [Revue de la pensée d’aujourd’hui; special issue, book guide from the Kojiki to Maruyama Masao]; June, 2005)

[13] Elise Tipton, Japanese Police State: Tokko in Interwar Japan (University of Hawaii Press: Honolulu, 1990), p. 23.

[14] Richard Mitchell, Thought Control in Prewar Japan (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1976), p. 142, Table 1. Source: Higuchi Masara, “Sayoku Zensorekisha no Tenko Mondai ni Tsuite,” 3–5.

[15] translation based on Justin Jesty’s translation, forthcoming in Literature for Revolution: An Anthology of Japanese Proletarian Writings, edited by Heather Bowen-Struyk and Norma Field

[16] translation by Justin Jesty

[17] “Spring 1932” was published in a truncated form in Kaizo in August 1932, and in a fuller form in Proletarian Literature in January and February 1933; “Moment by Moment” was rejected for publication by Chuo koron because of its content was not published until 1951, after Yuriko’s death and the end of the US Occupation. Eguchi Kan, “‘Spring 1932’ and ‘Moment by Moment’” (“1932 no haru” and “Kokkoku”), Miyamoto Yuriko: Sakuhin to Shogai (Miyamoto Yuriko: Her Works and Life), (Shinnihon shuppansha: Tokyo, 1976), p. 146.

[18] In December 1931, a cultural arts federation was formed: KOPF (Nihon Puroretaria Bunka Renmei, or Federacio de Proletaj Kultur-organizoj Japanaj). KOPF was a confederation of thirteen proletarian cultural groups like prokino (proletarian cinema), profoto, the music league, the writer’s league, etc. KOPF published populist proletarian journals like Proletarian Culture, Working Woman, The Friend of the Masses, and Little Comrade. Eguchi, p. 148

[19] “Spring 1932,” available online p. 20 (of print-out)

[20] Those arrested included Miyamoto Yuriko, Konno Dairiki, Nakano Shigeharu, Kubokawa Tsurujiro, Tsuboi Shigeji and others; later Kurahara Korehito was arrested. Miyamoto Kenji and Kobayashi Takiji managed to escape and go underground. (Eguchi, 146; all names but Konno’s)

[21] Eguchi, p. 150.

[22] Eguchi, p. 149.

[23] Richard Mitchell, Though Control in Prewar Japan (Cornell University Press: New York, 1976).

[24] Elise Tipton, Japanese Police State: Tokko in Interwar Japan (University of Hawai’i Press: Honolulu, 1991), p. 25–26.

[25] Richard Kim, “Pop Torture,” The Nation (December 10, 2005), republished on The Huffington Post (accessed September 9, 2006).

[26] Matt Feeney, “Torture Chamber: Fox’s 24 terrifies viewers into believing its bizarre and convoluted plot twists,” Slate (January 6, 2004) (accessed September 9, 2006).

[27] “We were writing the fourth, fifth, and sixth episodes when 9/11 happened, and the first show hadn’t even aired yet. Now, there was an explicit impact on that first show because it ends up with a plane being blown up. That obviously was very close to the bone, but it was also essential to the plot. So, it was recut to be less violent and visceral.” Michael Loceff, from interview with James Surowieki in “The Worst Day Ever: a 24 Writer Talks about Torture, Terrorism, and Fudging ‘Real Time,’” Slate (January 17, 2006) And it’s not the only time the writers anticipated real life: in season three, the evidence of nuclear weapons by three unspecified countries nearly leads the U.S. to war, except that in 24, the forgery is discovered in time and war is averted.

[28] “Cheney Roars Back: The Nightline Interview during his trip to Iraq,” Interview with ABC News’ Terry Moran, ABC News (Dec. 18, 2005).

[29] Ibid.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Deborah Pearlstein, “Reconciling Torture with Democracy,” The Torture Debate in America, edited by Karen J. Greenberg (Cambridge University Press, New York, 2006) (253–54).

[32] Heather MacDonald, “How to Interrogate Terrorists,” The Torture Debate in America (94–95)

[33] Available.

[34] interrogation: interviews with a point, “The Worst Day Ever: A 24 writer talks about torture, terrorism, and fudging ‘real time.’” By James Surowiecki, (January 17, 2006)

[35] Richard Kim, “Pop Torture,” The Huffington Post (Originally posted on The Nation), (12.10.2005)

[36] Alfred W. McCoy, The Question of Torture: CIA Interrogation, from the Cold War to the War on Terror (Metropolitan Books, Henry Holt and Company: New York, 2006), 5. In June 2006, allegations surfaced describing an immense global collusion: “More than 20 mostly European countries colluded in a ‘global spider’s web’ of secret CIA jails and flight transfers of terrorist suspects stretching from Asia to Guantánamo Bay, a rights watchdog said on Wednesday [June 7, 2006].” Jon Boyle, “Europe colluded with CIA over prisoners: watchdog,” (accessed August 1, 2006). In November 2005, The Washington Post reported on the network of secret prisons: “CIA Holds Terror Suspects in Secret Prisons: Debate Is Growing Within Agency About Legality and Morality of Overseas System Set Up After 9/11.” Dana Priest, The Washington Post (November 2, 2005) (accessed August 1, 2006).