Abstract: On January 3, 2022 the White House circulated the following joint statement of the five nuclear-weapons states on preventing nuclear war and avoiding arms races. It is reprinted here with a comment by John Gittings.

Joint Statement of the Leaders of the Five Nuclear-Weapon States on Preventing Nuclear War and Avoiding Arms Races

January 03, 2022

The People’s Republic of China, the French Republic, the Russian Federation, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, and the United States of America consider the avoidance of war between Nuclear-Weapon States and the reduction of strategic risks as our foremost responsibilities.

We affirm that a nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought. As nuclear use would have far-reaching consequences, we also affirm that nuclear weapons—for as long as they continue to exist—should serve defensive purposes, deter aggression, and prevent war. We believe strongly that the further spread of such weapons must be prevented.

We reaffirm the importance of addressing nuclear threats and emphasize the importance of preserving and complying with our bilateral and multilateral non-proliferation, disarmament, and arms control agreements and commitments. We remain committed to our Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) obligations, including our Article VI obligation “to pursue negotiations in good faith on effective measures relating to cessation of the nuclear arms race at an early date and to nuclear disarmament, and on a treaty on general and complete disarmament under strict and effective international control.”

We each intend to maintain and further strengthen our national measures to prevent unauthorized or unintended use of nuclear weapons. We reiterate the validity of our previous statements on de-targeting, reaffirming that none of our nuclear weapons are targeted at each other or at any other State.

We underline our desire to work with all states to create a security environment more conducive to progress on disarmament with the ultimate goal of a world without nuclear weapons with undiminished security for all. We intend to continue seeking bilateral and multilateral diplomatic approaches to avoid military confrontations, strengthen stability and predictability, increase mutual understanding and confidence, and prevent an arms race that would benefit none and endanger all. We are resolved to pursue constructive dialogue with mutual respect and acknowledgment of each other’s security interests and concerns.

***

Comment on the January 2022 Joint Statement of the Leaders of the Five Nuclear-Weapon States.

John Gittings

The Permanent Five (P5) of the Security Council often find it hard to agree, the more so in their role as the Nuclear Five (N5), but on two issues they are on the same page. The first, addressed in this new statement and often previously, is to profess full support for the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), against proliferation and indeed for the ultimate goal of a nuclear-free world, which entered into force in 1970. The second – not mentioned in the new statement but lurking in the background – is to condemn with one voice the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW), ratified by a sufficient number of UN member states for it to have come into force on January 21, 2021.

Image Source: The International Peace Bureau: Disarmament for Development

This new initiative (TPNW) may usefully be compared with the briefer and more cautious statement of two years before from the Foreign Ministers of the P5. Both statements have been issued in the context of the NPT – the first for the 50th anniversary of its ratification in 1970 and the second for the 2020 NPT Review Conference (postponed till January 2021 and now postponed again).

1. The stand-out new feature is its affirmation that “a nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought.” This is the identical wording to that of the 1985 joint Geneva statement by Reagan and Gorbachev which caused such consternation among “defence” establishments and allies (Margaret Thatcher told Reagan that giving up nuclear weapons would be “tantamount to surrender”).

The formula lay dormant for decades until it was revived by Presidents Biden and Putin in their online summit in June 2021. It was promptly repeated in a joint statement from Putin and Xi Jinping in the same month: the English version here is that “nuclear war has no winners and should never be unleashed.” (This part of the statement was not included in the summary issued by the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs).

2. Though not noticed in the current media coverage, the new statement also contains a stronger commitment (on paper at least) to the N5’s obligations under Article 6 of the NPT. In March 2020, the Foreign Ministers’ statement merely stated that

“We remain committed under the NPT to the pursuit of good faith negotiations on effective measures related to nuclear disarmament, and on a treaty on general and complete disarmament under strict and effective international control…” [my italics]

The 2022 statement is more explicit, stating the N5’s commitment to pursue

…negotiations in good faith on effective measures relating to cessation of the nuclear arms race at an early date and to nuclear disarmament and on a treaty… [wording as before]

It is an unfortunate fact of life (let us hope not of death) that vital issues of nuclear weapons threats and nuclear weapons diplomacy receive very little media attention. This latest move is no exception: there has been scant analysis of the factors that may have impelled the P5/N5 to move further. One of the few published analyses, in a commentary from the European Leadership Network (ELN), notes that

“The UK and France have privately made several arguments against reaffirming the statement [that a nuclear war must never be fought]. On one hand, some argue that the statement would not bring any demonstrable change to policy: that it is already implicit in policy, so need not be said. Conversely, some have expressed the opposite concern: that it would bring too much uncontrolled change, by generating further pressure on them for nuclear policy changes that they do not have the appetite for.”

Other reasons may be considered: One is that for both the UK and France, nuclear weapons are an important symbol of great power status which they would be loath to lose. Another is that with much smaller conventional forces, retention of the nuclear “deterrent” is seen by UK and French strategic planners to be essential, and not open to question even rhetorically.

The behind the scene negotiations by which the N5, within a few months, were able to speak with one voice is of great interest. I would suggest that one important inducement was the perceived need for more effective propaganda to counter the appeal of the TPNW. This treaty had been strongly opposed by the P5 in their joint statement in October 2018. Like the latest statement, this was pegged to the NPT (to the earlier 50th anniversary of its opening signature), but half of it was an unqualified denunciation of the TPNW. The five opposed the Treaty, they did not support it, they did not regard it as binding, and they called on all states that might consider supporting it to “reflect seriously” on its implications.

Significantly, the P5 did “not accept any claim that it [the TPNW] contributes to the development of customary international law; nor does it set any new standards or norms”. This assertion seems to reflect a hidden fear that the Treaty may indeed over time acquire the status of customary international law. These considerations will have been heightened by the Treaty’s coming into force in January 2021 (It now has 86 signatories and 59 ratifications.) The ratifying members, all of them non-nuclear states, included Algeria, Austria, Bangla Desh, Brazil, Indonesia, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Nigeria, the Philippines, South Africa, Thailand, and Vietnam, to mention some of the largest nations among the signers in Asia, Africa, Latin America, Europe and insular nations across the Pacific.

The arguments for the TPNW as an effective diplomatic instrument are now increasingly heard as well as those against it.

The P5 statement which we are considering here has had a cautiously positive reception from those who seek progress in moving towards a nuclear-free world. It has been welcomed by the Elders (the group of former world leaders working for peace, justice and human rights) with the hope that it will now lead to “concrete action”, and by the UN Secretary-General . Other views are more critical, pointing to the gap between words and actions such as the modernisation by all N5 powers of their nuclear forces and development of new weapons systems in direct contradiction to the provisions of the NPT. Indeed, it is clear that Article 6 of the Nuclear Proliferation Treaty, stipulating that

“Each of the Parties to the Treaty undertakes to pursue negotiations in good faith on effective measures relating to cessation of the nuclear arms race at an early date and to nuclear disarmament, and on a treaty on general and complete disarmament under strict and effective international control,”

has been honored in the breech. The reality is that, far from pursuing measures relating to cessation of the nuclear arms race, the nuclear powers, including but not limited to the P5, have consistently expanded their nuclear capacity and its extension to outer space.

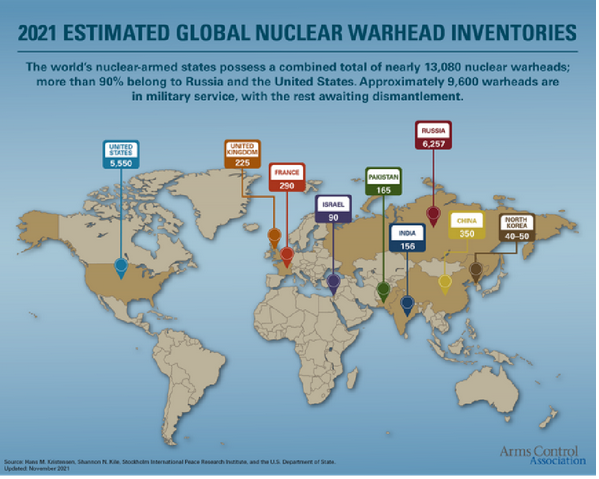

Nuclear Weapons: Who Has What at a Glance

Source: Arms Control Association

These caveats are entirely valid. But the reality is that the new statement, while seeking to moor the P5’s stand on nuclear weapons in more user-friendly ground, and to counter the appeal of the TPNW, may have the opposite effect. It betrays a growing defensiveness and opens up new lines of criticism for anti-nuclear weapons advocacy.

- The basic illogic of deterrence theory is exposed in the same paragraph where the commitment is made. For if a nuclear war must never be fought, what is the sense of the threat implied in their possession of nuclear weapons that they may use in certain situations? The deterrence factor claimed for them is either a bluff which may be called, or a genuine threat to do something which must “never” happen.

- It is now open to any interviewer with e.g. the US Secretary of Defence (or their UK or French counterparts), or the NATO Secretary-General, or the Russian Foreign Minister, or the Chinese MFA spokespersons, to ask outright how the statement squares with being prepared to use nuclear weapons if “deterrence” fails. And where does it leave the stated (or implied) willingness of the N5 powers to use nuclear weapons pre-emptively or in conditions of a presumed non-nuclear threat?

- The statement’s re-assertion of the N5’s NPT Article 6 commitment also opens up strong lines of challenge. How can this be squared with new weapons projects such as the US’s Global Positioning System programme, Russia’s hypersonic missile test, and the nuclear modernisation programmes of the other three powers? See Lawrence Wittner’s superb analysis of “The Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons and the World’s Future.” And if the goal of a nuclear-free world is so important, then the N5 should have already developed a road map on how to achieve it, rather than rely on vague professions of good faith.

These and other important questions are waiting to be put to the nuclear powers, but the real question is: who will ask them?