Abstract: This article surveys the highlights of Japanese political assassination from 1909 to 2022 through the commemoration of the victims and photographs of the major sites in Tokyo.

Keywords: Political Assassinations, Abe Shinzo, Japanese history, Heritage

All societies have a history including periods punctuated by political violence. Contemporary Japan, a nation with some of the lowest rates of violent crime in the world, is no exception. One hundred thirteen years apart, Japan’s first prime minister, Ito Hirobumi, and its longest serving prime minister, Abe Shinzo, fell to assassins, Ito at age 68 in 1909, and Abe at 67 in 2022. This article examines some of the distinctive patterns of violent history in Japan, and particularly the ways in which they are commemorated in Tokyo, the national capital. In contrast to the predominance of anonymous gun killings in the United States in recent decades, Japanese assassinations are notable for targeting numerous figures of national and international significance across Japan and throughout parts of the pre-1945 Japanese empire.

Both Ito and Abe had ancestral roots in the powerful domain formerly known as Choshu, now Yamaguchi Prefecture. Ito, who at the time of his death was serving as Resident-General of Korea, was gunned down by Korean independence activist An Jung-geun on October 26, 1909 at Harbin Station in China. An was hanged at Ryojun Prison in Port Arthur on March 26, 1910, five months before Japan formally annexed Korea.

Figure 1: Bust of Ito Hirobumi at his grave in Shinagawa, Tokyo. Photo by the author.

Abe was fatally shot in Nara on July 8, 2022 by a 41-year-old unemployed former Self-Defense Force member, Tetsuya Yamagami, while the former Prime Minister campaigned on behalf of an ally for the upcoming lower house elections. For his weapon Yamagami had used a homemade gun he produced following instructions on the internet. His stated motive for his crime was anger over Abe’s ties to the Unification Church, founded in 1954—coincidentally the year Abe was born—by Korean evangelist Moon Sung Myong (1920–2012). Yamagami explained that his mother’s donations to the Japan branch of the church had bankrupted his family.

While neither Ito nor Abe met their end in Tokyo, Japan’s capital has been no stranger to assassinations, as testified by numerous markers and memorials found throughout the city. From April 2021 I set out to visit and photograph as many sites as I could access. These first appeared as a photo essay in the July 2021 issue of Number 1 Shimbun, the house organ of the Foreign Correspondents’ Club of Japan. More than a year later, I am still finding new ones. By focusing on one particular type of historical event and cataloging some of the major events into an article, I hope to provide a fresh view of Japanese political thought and praxis over the past century and a half.

On March 24, 1860 Tairo (great elder) Ii Naosuke, the most powerful official in the Tokugawa bakufu, was approaching the Sakuradamon gate of Edo castle when his retinue was attacked by a troupe of 17 shishi (“men of high purpose”) from the Mito domain (and one from Satsuma). A heavy snow was falling, and the oilskin protective clothing worn by Ii’s guards made it difficult for them to draw their swords quickly. During the bloody melee, Ii, age 44, was dragged out of his palanquin and decapitated.

Figure 2: Bilingual signboard at Sakuradamon gate. Photo by the author.

Figure 3: The Sakuradamon gate as it appears today. Photo by the author.

Two years earlier, Ii had ordered the Ansei Purge, jailing, exiling and in some cases executing 100 individuals suspected of disloyalty to the Tokugawa government. The killers also objected to Ii’s having negotiated, and in July 1858 signed, the Treaty of Amity and Commerce between Japan and the United States, as well as subsequent treaties with European powers.

Romulus Hillsborough’s 2017 work, Samurai Assassins: “Dark Murder” and the Meiji Restoration, 1853-1868 explains the background, circumstances and description of the Sakuradamon Incident. The book also details the unsuccessful attempt on the life of Ando Nobumasa, Ii’s successor, in a similar attack outside the Sakashita gate of the castle on February 13, 1862.

Figure 4: Monument to Ii’s assassins, who converged at the Atago Shrine before embarking on their bloody quest. Photo by the author.

Figure 5: Grave of Ii Naosuke at the Gotokuji Temple in Setagaya Ward. Photo by the author.

Since the signing of the Convention of Kanagawa in March 1854 and subsequent opening up of treaty ports around Japan, foreign soldiers and members of diplomatic legations were targeted by xenophobic samurai on numerous occasions.

On January 29, 1860, Kobayashi Denkichi, interpreter to the British legation, was fatally wounded by two samurai outside the gate of the Tozenji temple in Takanawa, just off the Tokaido road linking Edo to Kyoto. The Wakayama native’s fishing boat had gone adrift when he was rescued by an American vessel and taken to San Francisco, where he learned English. He later traveled to Hong Kong, acquired British nationality and accompanied Great Britain’s first ambassador, Sir John Rutherford Alcock, to Japan in 1858.

Figure 6: Gate of the Tozenzi temple, site of Great Britain’s first legation in Edo where Kobayashi Denkichi was assassinated. Photo by the author.

A year after Kobayashi’s murder, on January 14, 1861, the Japanese interpreter of U.S. Ambassador Townsend Harris, 28-year-old Dutch-born Henry Heusken, fell victim to a similar fate. Returning on horseback from a dinner with a Prussian official, he was attacked by a group of shishi from the Satsuma domain at the Nakanohashi bridge near Azabu Juban. Although eviscerated by sword cuts he managed to flee to the nearby American Legation at Zempukuji, but was pronounced dead shortly after midnight. Heusken left behind a Japanese wife and child.

The killers of Kobayashi and Heusken were never identified or brought to justice. The two are buried in close proximity in the Korinji cemetery in Azabu.

Figure 7: Grave of Townsend Harris’s interpreter Henry Heusken at Korinji temple in Azabu. Photo by the author.

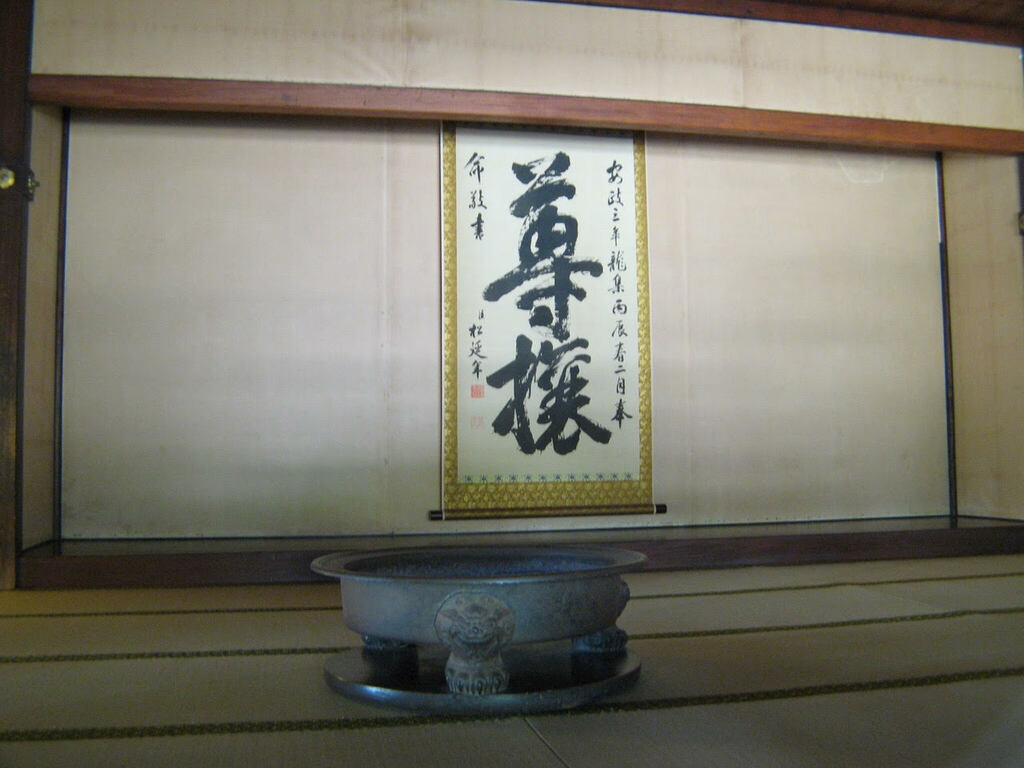

Figure 8: “Sonjo” scroll hanging at the Kodokan academy in Mito, where young samurai were imbued with the slogan “Sonno Joi” (revere the Emperor and expel the barbarians). Photo by the author.

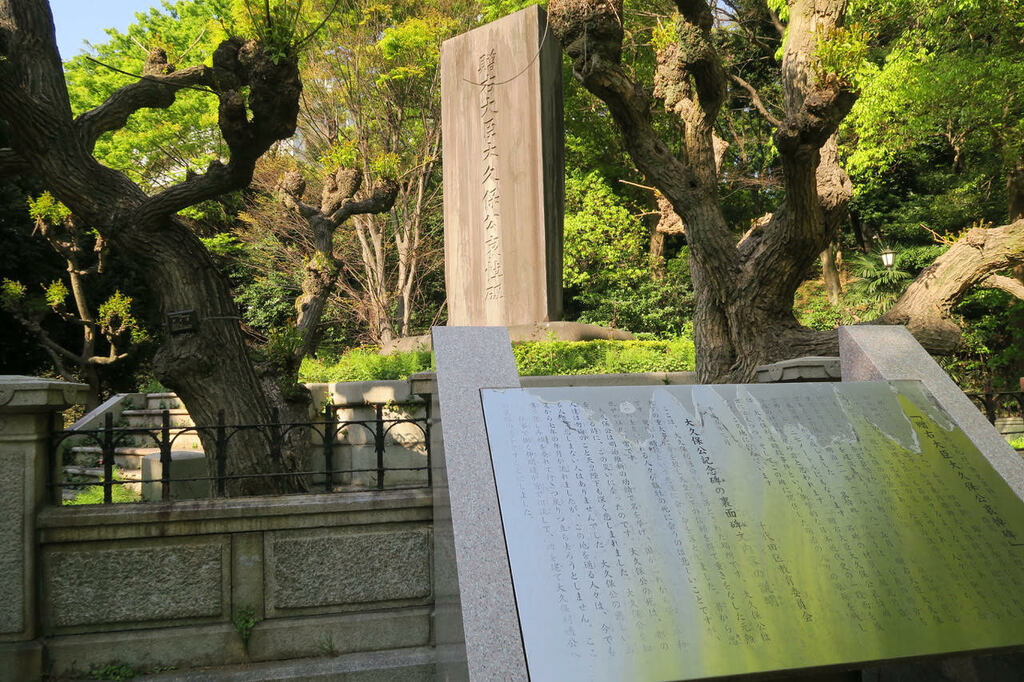

Japan’s restoration to imperial rule from January 3, 1868 would eventually leave a large class of disenfranchised samurai, resentful over the loss of their power and class privileges. On May 14, 1878, the carriage of Lord of Home Affairs Okubo Toshimichi was attacked by a group of ex-samurai from the Kaga domain (Ishikawa Prefecture). The 47-year-old Okubo, a native of Satsuma (Kagoshima) and remembered as one of the three great nobles who led the Meiji Restoration, was literally cut to ribbons and died on the spot. The monument to Okubo and an explanatory bilingual signboard are situated in Shimizudani Park in Kiyoi-cho, directly across the street from the Hotel New Otani.

Figure 9: Monument at the site of Okubo Toshimichi’s assassination in May 1878. Photo by the author.

Figure 10. Signboard at Shimizudani Park, site of Okubo’s assassination. Photo by the author.

On Feb. 11, 1889, a national holiday and the same day on which the Meiji Constitution was promulgated, 43-year-old Minister of Education Mori Arinori was stabbed while exiting the Prime Minister’s Office by an assassin wielding a kitchen knife. He died the following morning. The University College of London-educated Mori, who had formerly served as Japan’s first ambassador to the United States, was a controversial figure who advocated some radical ideas, including replacing the Japanese language with English.

Mori’s 23-year-old killer, Nishino Buntaro, was outraged by Mori’s alleged failure to follow religious protocol during a visit to the Ise Shrine two years earlier. Mori was said to have not removed his shoes before entering and had pushed aside a sacred curtain with his walking stick.

On June 21, 1901, Hoshi Toru, the first Japanese to qualify as a barrister in the U.K., and a former communications minister, was cut down by Sotaro Iba, a fencing master, during a meeting at Tokyo City Hall (which at that time was in Yurakucho). Hoshi was 51.

Eventually the Meiji Emperor himself would become a target of anarchists. On November 3, 1907, the Emperor’s birthday, a holiday then feted as Tencho Setsu, a disrespectfully worded flyer, addressed to Emperor Mutsuhito (Meiji), was found outside the door of the Japanese consul general in San Francisco.

“Your lowliness, Mutsuhito-kun,” it condescended, “Pathetic little Mutsuhito-kun. Your lowly fate is soon to be sealed. A bomb will be placed beneath you, ready to explode. Farewell, your lowliness.”

Thus alerted, police kept close tabs on anarchists and other radicals. In May 1910, a patrolman in Matsumoto City, Nagano Prefecture reported to his superiors that a man named Miyashita Taikichi had obtained a suspiciously large number of tin cans. On May 17, 1910, police raided Miyashita’s place of employment and discovered bomb-making implements. He was arrested, and a nationwide sweep of known radicals ensued, resulting in their indictment in a plot by anarchists to assassinate Meiji on November 3, 1910.

The alleged conspirators in the so-called Taigyaku Jiken (Great Treason Incident) were believed to have been instigated by their erstwhile ringleader, radical journalist and newspaper publisher Kotoku Denjiro (also known by his nom de plume Kotoku Shusui), who was the likely author of the threatening letter in San Francisco three years earlier.

After a perfunctory trial by the Supreme Court, in which the accused were prohibited from submitting exculpatory evidence or summoning witnesses in their defense, twelve individuals including Kotoku and his mistress, Kanno Sugako, were found guilty and in January 1911 hanged at Ichigaya Prison. Another dozen were spared the gallows but sentenced to long prison terms.

Figure 11: Monument erected by the Japan Bar Association at the site of the gallows at the former Ichigaya Prison, where Kotoku Denjiro and 11 other anarchists were hanged for plotting to assassinate the Meiji Emperor. Photo by the author.

Figure 12: Nakamura City residents flock to Kotoku’s grave each year on the anniversary of his execution. Photo by the author.

Figure 13: Kotoku memorabilia on display at the public library in his home town of Nakamura City, Kochi Prefecture. Photo by the author.

Kotoku’s execution was to have repercussions 13 years afterward, when on 27 December, 1923, Namba Daisuke, son of a Diet member from Yamaguchi, fired shots at the carriage carrying Crown Prince and Regent Hirohito at the Toranomon intersection while en route to a Diet session. Hirohito was unharmed.

Figure 14: Memorial near Toramon subway station where Crown Prince and Regent Hirohito was targeted by an assassin in December 1923. Photo by the author.

The 24-year-old Namba, a dedicated communist, told interrogators he had been moved to avenge Kotoku’s death. He was convicted of treason and hanged 11 months later, on the same Ichigawa Prison gallows as was Kotoku.

Namba’s father, Namba Sakunoshin, refused to retrieve his son’s body. To atone for his son’s crime, he barricaded himself in a small room in his mansion, lingering for six months before dying of starvation at age 61.

As fate would have it, the elder Namba’s seat in the Diet was eventually taken by Matsuoka Yosuke, who as head of the Japanese delegation to the League of Nations led the walkout in 1933. As Japan’s minister of foreign affairs, Matsuoka soon thereafter set the stage for Japan’s signing the Tripartite Pact with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy.

Assassinations also took place in response to the expansion of Japan’s Asian empire. One of the most notorious was the assassination of Korea’s 43-year-old Empress Myeongseong (also referred to as Empress Min) on October 8, 1895, by a mixed group of Japanese military, civilians and Korean collaborators. The first Sino-Japanese war had turned parts of Korea into a battleground, and upon its conclusion in April 1895 Japanese targeted the Empress for having advocated stronger ties between Korea and Russia, at Japan’s expense.

In the early morning hours of June 4, 1928, members of the Japanese Kwantung Army attached a powerful bomb to the underside of a railway trestle at Huanggutun, an intersection of two rail lines just outside of the old Manchu capital of Mukden (present-day Shenyang). As the train carrying Manchurian warlord Zhang Zuolin passed underneath, the device was set off, killing Zhang as he sat in his private rail car playing mahjong.

Figure 15: Actual size reproduction of the train in which Zhang Zuolin was assassinated by members of Japan’s Kwantung Army at Huanggutun, Shenyang (formerly Mukden) in June 1928. Photo by the author.

With its paramount military leader dead, northeast China was ripe for a takeover, which the Kwantung Army achieved on September 18, 1931 with a false flag bombing incident on the South Manchurian Railway near Mukden, which it blamed on Chinese guerrillas. The puppet state of Manchukuo, with its capital at Hsinching (Changchun) and with Aisin-Goro Puyi as emperor, was founded on February 16, 1932.

Back in Japan, outbreaks of political violence continued to chip away at the underpinnings of Japan’s “Taisho Democracy.” The list of plots, assassination attempts and successful assassinations reads like a veritable “Who’s Who” of Japan’s oligarchs, politicians, business leaders and intellectuals as well as including revolutionary, anti-colonial and anti-imperial activists. Among the targets were the heads of the Yasuda and Mitsui zaibatsu, Yasuda Zenjiro (killed in 1921) and Dan Takuma (1932). Two others—Yomiuri Shimbun publisher Shoriki Matsutaro (1935) and constitutional scholar Minobe Tatsukichi (1936)—were wounded by ultranationalists but survived.

During the first three decades of the 20th century, the prime minister of Japan became a high-risk occupation. A plaque under the rotunda of the Marunouchi South Exit indicates where Prime Minister Hara Takashi (65) was stabbed to death by a railway worker on November 4, 1921. A second, mounted on a pillar close to the wicket of the Tokaido Shinkansen, indicates the spot where, on November 14, 1930, Prime Minister Hamaguchi Osachi was shot by a member of an ultranationalist secret society.

Figure 16: Small white hexagon on the floor of Tokyo Station (Marunouchi South Exit) indicates where PM Takashi Hara was standing at the moment he was slain. Explanation is posted on the wall behind it. Photo by the author.

Figure 17: Square in Tokyo Station indicates where PM Isachi Hamaguchi was standing when attacked in 1930. The details are explaned on the pillar in the background. Photo by the author.

Hamaguchi had infuriated opponents of the London Naval Treaty, which he had supported as an austerity measure to deal with Japan’s economic crisis. He lingered for nine more months but never recovered from his wounds, passing away at age 61.

In 1943, veteran journalist Hugh Byas (1875–1945), a Scot who for several decades reported from Tokyo for The Times of London and The New York Times, published Government by Assassination. His book took note of how perpetrators of assassinations gradually shifted from civilians to members of the military. As Byas wrote,

Some of the young officers…had shown that the Japanese army was infected with ideas supposed to be confined to the fanatics of the patriotic societies….When it appeared that the army was in the movement, the Black Dragon Society and all the others became supers [sic] on the stage. There were no more political murders by civilians. The patriotic societies relapsed into anti-foreign and pro-war mobs, the role for which they were naturally fitted. The army installed itself in power with the concurrence of a docile nation intoxicated by foreign war, its civilian leaders terrorized by assassination.

On May 15, 1932, 11 junior Naval officers stormed into the office of 76-year-old prime minister Inukai Tsuyoshi. Their leader exclaimed “Dialogue is useless!” before opening fire, killing him.

Inukai’s efforts to rein in the military had made him enemies, but his death at the hands of young naval officers came as a surprise. Two and a half months earlier he had withheld Japan’s formal recognition of Manchukuo, greatly displeasing radicals in the army.

Reporting on Inukai’s assassination, Byas wrote, “The man in the street was startled but not alarmed. A Japanese neighbor was a little amused by my excitement. ‘The Japanese people will not be very angry about the prime minister’s murder,’ he said; ‘many of us think the politicians needed a lesson.’”

The assassination of one of the Japanese army’s most influential leaders, lieutenant-general Nagata Tetsuzan, by lieutenant-colonel Aizawa Saburo on August 12, 1935, underscored the bitter factionalism between the Army’s moderate Tosei-ha (Control faction), which Nagata headed, and the more radical Kodo-ha (Imperial Way faction), to which Aizawa belonged. In a nutshell, the Tosei-ha, led by Nagata, was somewhat more moderate, and sought to forge alliances with industrialists and oligarchs to build up Japan’s strength before planning war. The more radical Kodo-ha, led by army general Araki Sadao, was supported by soldiers whose families had been impoverished by the depression. The Kodo-ha advocated purging the government of “corrupt” politicians and bureaucrats, seeking to realize a “Showa Restoration” under a “purified” government under direct imperial rule.

Nagata, who headed the key post in the Ministry of War’s Mobilization Section, had been a mentor of General Tojo Hideki from their service in Europe after World War I. His death served as the catalyst for a full-fledged rebellion six months later. On February 26, 1936, some 1,500 soldiers under officers belonging to the Imperial Way faction marched into government offices and the homes of top government leaders to demand a “Showa Restoration.”

At the Prime Minister’s residence, rebel troops of the Kodo-ha mistook army general Matsuo Denzo for prime minister Keisuke Okada and executed him by machine gun. (Okada escaped by hiding in a closet, but he resigned 12 days later.) Saito Makoto, Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal was killed at his home in Yotsuya. General Watanabe Jotaro, Inspector General of Military Training, one of the army’s three key positions, was machine gunned at his home in Ogikubo as his wife and daughter looked on.

The four important figures assassinated that day included 81-year-old Minister of Finance Takahashi Korekiyo who had previously served as president of the Bank of Japan and prime minister. At gunpoint, a servant led two officers into his bedroom, where they killed Takahashi as he slept.

Figure 18: Statue of Takahashi Korekiyo at the site of his former residence in Aoyama. Photo by the author.

Figure 19: Statue of the goddess Kannon erected on the spot in Shibuya where the Feb. 26 assassins and their leaders were executed. Photo by the author.

Takahashi’s former residence became a memorial park next to the Canadian Embassy in Aoyama. The house in which he was slain still stands, and can be visited at the Edo-Tokyo Open Air Architectural Museum in Koganei City.

Figure 20: Takahashi Korekiyo’s former house was moved to an outdoor museum in Koganei. He was killed while sleeping in an upstairs bedroom. Photo by the author.

While a number of assassinations and assassination attempts that occurred during the postwar period stand out, the most sensational was the killing of Japan Socialist Party chairman Asanuma Inejiro on October 12, 1960, by Yamaguchi Otoya, a 17-year-old student.

At a televised political debate by party heads attended by prime minister Ikeda Hayato, Yamaguchi had slipped through a cordon of police who were trying to clear a group of noisy hecklers from the wings of the stage and, flinging himself at his target, drove a yoroidoshi (a type of short sword designed for piercing samurai armor and grappling in close quarters) into Asanuma’s aorta. NHK TV footage of the Asanuma assassination can be viewed on YouTube here.

The following year, Mainichi Shimbun photographer Nakao became the first Japanese to be awarded Pulitzer Prize for his photograph, which captured the physically imposing Asanuma—already mortally wounded—extending his hands in a futile attempt to ward off the diminutive Yamaguchi’s second thrust.

Figure 21: Prizewinning photo shows the already mortally wounded Asanuma attempting to ward off his assailant’s second attack. Photo by Yasushi Nagao.

Asanuma was a popular but controversial figure. He had infuriated Japan’s rightists the previous year when, during a visit to Beijing, he remarked “Amerika teikoku shugi ha nicchu ryokoku jinmin kyodo no teki de aru” (American imperialism is the common enemy of the peoples of Japan and China.) After he was photographed disembarking from his return flight wearing a Mao suit, rightists began clamoring for his assassination.

In an e-mail, the former chief of Tokyo’s UPI bureau Glenn Davis wrote to me, “I would have liked to have had the opportunity of asking why Otoya Yamaguchi, that 17-year-old, got a front row seat. Certainly the police knew he had been arrested on numerous occasions for violent behavior and that he was a disciple of Akao Bin (leader of the Greater Japan Patriotic Party), who had repeatedly called for Asanuma’s assassination. As far as I know, very few Japanese journalists have delved into that obvious set-up.”

Davis continued. “When I later interviewed Akao at his home, he had a huge painting hanging on the wall of his living room portraying the moment of the assassination, with flames surrounding the assailant, as if it was a moment of heroic significance.”

Three weeks after Asanuma’s murder, Yamaguchi, by this time occupying a solitary cell at Nerikan, Tokyo’s juvenile classification facility, fashioned a rope from his bedsheet and hanged himself from a light fixture. On the wall, he’d used an amalgam of tooth powder and water to write “Long live the Emperor” and “Would that I had seven lives to give for my country”—a reference to the last words of 14th-century samurai Kusunoki Masashige, who in 1336 was killed at the battle of Minatogawa at what is now modern-day Kobe. During WW2, Kusunoki was regarded as a kind of patron saint for Kamikaze pilots, who saw his sacrifice for the emperor as a role model.

In November 1971 Asanuma’s widow Kyoko unveiled a bas-relief statue of her husband paid for with donations from supporters and Socialist Party members. It was mounted in the foyer of the Hibiya Public Hall; but within one month it had been defaced by an unknown person or persons, probably using a hammer. To avoid further vandalization, the bas-relief was concealed behind a wall panel and eventually forgotten, until its re-discovery in 2015. It remains behind the panel and is unlikely to ever be displayed again.

Figure 22: Asanuma’s grave in Tama Cemetery, west Tokyo. Photo by the author.

Fifty years to the day of Asanuma’s assassination—on October 12, 2010—the Otoya Yamaguchi Appreciation Society held a ceremony to commemorate Yamaguchi’s “heroic” act.

Figure 23: Fifty years after his act, Yamaguchi Otoya supporters held a memorial ceremony on the stage of Hibiya Public Hall where he killed Asanuma. Photo by Brett Bull.

“We are here to honor Yamaguchi’s deliverance of justice to Asanuma,” intoned the Greater Japan Patriotic Party’s Takashi Funakawa.

In a parallel universe, it would be akin to the Sons of Confederate Veterans renting out Ford’s Theater on April 14 to honor John Wilkes Booth.

Bibliography

Bessatsu Takarajima 1064, Showa-Heisei Nihon Tero Jiken-shi, Takarajima-sha, 2004.

Byas, Hugh, Government by Assassination, Alfred A. Knopf, 1942.

Hillsborough, Romulus; Samurai Assassins: “Dark Murder” and the Meiji Restoration, 1853-1868; McFarland; Illustrated edition (March 22, 2017).

Ichisaka Taro, Ansatsu no Bakumatsu Ishin-shi, Chuko Shinsho, 2020.

Murofuse Tetsuro, Nihon no Terorisuto, Ushio Shuppan-sha, 1986.

Rekishi to Jimbutsu Tokushu: Kindai Nihon no Ansatsu; Chuo Koron-sha, March 1976.

Sunday Mainichi ga Mita 100-nen no Sukyandaru: “Majime no Hyohon” 17-sai ni yoru Shakai-to-Iincho e no teroru, Sunday Mainichi (July 3, 2020), Mainichi Shimbun-sha, 2020.