Abstract: This paper examines Japan’s complex infrastructure of cemeteries that preserve the memories of Japanese soldiers who died during military conflicts, while simultaneously maintaining a literal and figurative distance from more controversial sites of memory, such as the Yasukuni Shrine in Tokyo. Yasukuni has been at the center of “memory debates” in East Asia, making it difficult for unobtrusive forms of commemoration such as war cemeteries to gain a significant profile. Japanese war cemeteries are scattered around the country and the East Asian region and contain ossuaries hosting the actual remains of the dead, cenotaphs, as well as individual and collective tombs. Their physical configuration provides an educational tool of transnational scope, involving, among others, displays of commemoration and mourning dedicated to non-Japanese ‘enemy’ soldiers. In addition, the presence of Japanese cemeteries and monuments for the war dead built and maintained throughout Southeast Asia, in Japan’s former colonial and wartime territories, amplifies the relational and transnational composition of the notion of a ‘national space’ of mourning. By looking at two Japanese sites, Sanadayama Cemetery in Osaka and the Japanese Cemetery in Johor Bahru, Malaysia, I highlight the importance of the cemetery as a locus of transnational memory and a reverent educational resource which moves beyond the picture of Japanese war memory as simply “reactionary” or “revisionist.” I argue that these two sites allow for an interpretation of commemorative spaces at the heart of contested war memories that neither conform to, nor are constrained by the debates surrounding Yasukuni.

Keywords: cemeteries, war memorials, war dead, Asia-Pacific War

Introduction

In this article, I analyze Japan’s cemeteries for the war dead both at home and abroad as a potential alternative to the domestic memorial landscape of the Asia-Pacific War (1931-45) which is dominated by the controversial Yasukuni Shrine. At that shrine, among approximately 2.5 million war dead are fourteen Class A war criminals honored as deities or “gods,” leading to the accusation that Japan misrepresents its wartime past and refuses to adequately atone for it (Kingston 2007; Takahashi 2005; Takenaka 2015). Most notably, these circumstances have been assiduously denounced by China and South Korea as misguided and insulting, with most criticism leveled at purported tactless exaltations of militarism and nationalism that reopen old historic wounds, transgressions for which Yasukuni is often excoriated (Saaler 2005). The fallout from this cultural wrangling and a renewed focus on the legacies of the Asia-Pacific War have had a serious inimical effect on relations between Japan and its neighbors, leading to diplomatic discord and rising regional tensions (Breen 2008; Hock 2007; Jager and Mitter 2007; Rose 2007; Saaler and Schwentker 2008; Shin et al. 2007).

The focus on Yasukuni also causes neglect of a secular institution connected to the memory of those who died in the conflagrations of the Asia-Pacific War: Chidorigafuchi National Cemetery for the War Dead (Chidorigafuchi Senbotsusha Boen) built in Tokyo in 1959. Originally designed as a “tomb of the unknown soldier,” Chidorigafuchi was configured to include the remains of unidentified combatants and civilians. Unlike Yasukuni which only hosts the “souls” of the war dead (or eirei, which carries special, honorable connotations) and refuses the enshrinement of unidentified soldiers or any civilians, Chidorigafuchi inters actual remains. However, the acceptance of Chidorigafuchi as a national site of mourning in opposition to or even complementing Yasukuni has been beset with problems (Saaler 2005, ch. 2; Trefalt 2002). Most significantly, it has been inexorably sullied with the accusation that it does an insufficient job in recognizing Japan’s role in starting the Asia-Pacific War, to the chagrin of victims in neighboring countries who have suffered the brunt of the conflict. For all its respectable intentions to remove the stigma of militarism and religious nationalism that characterize Yasukuni in the international imagination, Chidorigafuchi, too, comes up short in explicitly addressing Japan’s role in the Asia-Pacific War and in perpetrating atrocities such as the Nanjing Massacre or the actions of Unit 731.

Since 1952, the Ministry of Health and Welfare (Kōseishō, later renamed the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare or Kōseirōdōshō) has worked to repatriate the remains of the Japanese war dead from battlefields around the Pacific, and to eventually put them to rest at Chidorigafuchi.1 In other parts of Asia, the Ministry has also erected and continues to maintain memorials, such as cenotaphs or cemeteries, which host the remains of Japanese nationals or memorialize them. One would reasonably compare these efforts to those of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission or Germany’s War Grave Commission (Volksbund Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge). However, the positions that these two institutions take, the universal character of their practices and their global diplomatic outreach surpass Japan’s performance in the field. Different from the United Kingdom or Germany, Japan’s cemeteries for the war dead lack centralized management and organization and rely largely on (sometimes shaky) local-based operational infrastructures. Nevertheless, against these imperfections or inadequacies, Japan’s war cemeteries, as a collective, expand the perimeters of national borders by incorporating a contested historical past within customary funerary artifacts (like graves, gravestones and monuments) that connect to a global event (i.e. the Asia-Pacific War) and to a global audience. In other words, these cemeteries serve a variety of important social and political configurations that are quite distinct from regular, “non-war” cemeteries.

In this paper, through two case studies, Sanadayama Cemetery in Osaka and the Japanese Cemetery in Johor Bahru in Malaysia, I show how cemeteries for the war dead provide material proof of the enormity of Japan’s expansionist and wartime past. Sites such as these offer a different understanding of Japan’s overseas entanglements and their human cost at a time when the politicization of historical memory sees a worldwide upsurge and the “death of the witness” (Nichanian 2016), exemplified by the loss of those who survived and could corroborate the ravages of war from first-hand experiences, is tragically prevalent. I argue that, in contrast to Yasukuni Shrine, the past represented at these two sites of memory is not always infused with demagogic appeal; instead, it carries educational and historical potentials that are revealingly and sensitively transnational and conciliatory. Moreover, the historical discourse reflected in these cemeteries – in the inscriptions of names, places and battles, for example – reconfigures the ubiquitous “victim narrative” (Orr 2001) characteristic of Japan’s attempts to deflect from its wartime crimes and focus on its own trauma. Instead, these cemeteries include material attestations of a militaristic nation and empire responsible for a significant number of deaths across a global expanse, effectively connecting these sites to pre- and post-war landscapes of historical violence. In other words, these cemeteries offer physical evidence of the material and human destruction caused by Japan’s expansionist wars. In addition, the human element affixed to these sites of memory discloses the prospect for a transnational dialogue by shifting or “re-territorializing” (McDonald 2017) nation-building and national identity beyond Japan’s domestic borders to foreign lands, specifically, to former colonies, battlefields and occupied territories.2

The Significance of War Cemeteries – Japanese and Global Perspectives

What exactly do cemeteries do? Apart from their obvious functional purpose of inhumation and funeration, cemeteries leave the most traces on the ground and in the ground – and, correspondingly, in historical records – through the work of the dead who, as Thomas Laqueur aptly observed, “make social worlds” (2015, 1). This social function transforms cemeteries into what Pierre Nora famously described as “lieux de mémoire” (Nora 1989), sites or “realms” of memory inscribed with valuable cultural and national significance which preserve and produce the historical continuity of any community. In the case of war cemeteries, this continuity is bolstered by a symbiosis between ideological and emotional responses attached to the ideas of nation and state on the one hand (Juneja 2009), and expressions of national identity (Lemay 2018) on the other. This is encapsulated by the special reverence which one accords to the “heroic” or “patriotic” dead resting in these spaces. At war cemeteries, adherence to an ethnic group and collective mobilization in the face of national adversity are carved in the gravestones, monuments, statues, cenotaphs and other material signifiers erected for those who perished, were killed or disappeared as a consequence of armed conflict. As a result, cemeteries are integral to what George L. Mosse called “the cult of the fallen soldier” (1990) in that they stimulate – both in times of war and peace – the necessary heroism to motivate others to fight and sacrifice one’s life in battles carried out to protect the community or nation. But even more than offering generic eulogies to victims, fighters and other human instruments of warfare, cemeteries for the war dead exist in the dichotomy between “inscribed” (Coser 1992) and “embodied” (Connerton 1989) memory, the interaction between objects and sociological ritual reminding, re-living and re-creating history. Cemeteries constitute a physical record of a community’s former occupants and are a source of raw data. They are spaces of collective commemoration and mourning, filling in as sites of remembrance and history, outside of oral or textual forms of memory. Lastly, they also function as a political tool, as the memory and history they preserve can be manipulated and instrumentalized for various objectives. These various interpretations can be applied universally to all war cemeteries found around the world, including in the case of Japan.

Estimates differ as to the number of former Army and Navy cemeteries in Japan. Historian Harada Keiichi puts the number at seventy-nine (2013, 29). Yamabe Masahiko, however, gives a more detailed estimate of ninety-four military cemeteries, eighty-seven for the Army and seven for the Navy (2003). Other sources estimate the number of cemeteries at between eighty-seven and ninety based on documents compiled when the military assets – including cemeteries and shrines to commemorate the war dead – were transferred from the control of the Ministry of Finance (Ōkurashō) or the Ministries of the Army and the Navy to the Ministry of Health and Welfare between August 28 and October 25, 1945 (Harada 2002). Today, these cemeteries are either state-owned, in the hands of local administrations or are managed by non-governmental organizations and volunteers.

Whatever their exact number may be, these spaces amplify a purportedly national “material geography of memorialization” (Graham 2011) instituted for the memory of the war dead that come under many guises and are ubiquitous throughout Japan in the forms of simple stone monuments (ishibumi); signposts; cenotaphs (ireihi); monuments for the “loyal spirits” of those who died in battle (chūkonhi); and pagodas or towers consecrated to the “loyal spirits” (chūreitō). Japanese war cemeteries can exist independently from or in tandem with these other forms of memorial objects and spaces. In addition, shrines dedicated to the spirits of the war dead (shōkonsha) and nation-protecting shrines (gokoku jinja), regional versions of Yasukuni Shrine, host and sanctify the souls of the war dead, performing a commemorative role similar to the cemeteries under discussion. The war dead, therefore, are embedded in Japan’s landscape in a multitude of ways, with Yasukuni Shrine just being one site of worship or commemoration among many, notwithstanding the intense attention it receives.

This “geography of memorialization” extends to spaces outside of Japan’s current national borders.3 While many sites outside of Japan are not exclusively dedicated to the war dead and, thus, it would be incorrect to describe them as military cemeteries or cemeteries for the war dead identical in form and function to those established and maintained domestically, they nevertheless are part of the network of institutions constituting Japan’s diverse memorial landscape. In the case of numerous Japanese cemeteries scattered throughout Southeast Asia, that past is circumscribed by a process of colonization and occupation carried under the doctrine of “Southern Expansion” (Nanshin-ron) according to which Japan sought to penetrate the region through economic and territorial expansion (Shimizu 1987). It is more accurate to refer to this kind of overseas Japanese cemeteries as ‘colonial cemeteries’ for while the individuals hosted or commemorated in these places are not all directly connected to Japan’s wars, they are, nevertheless, integral to the history of the Japanese Empire, the imperialist project of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere (Dai Tōa Kyōeiken), as well as military incursions and the resultant (war) dead.

I am drawing here on a miscellany of historiographical arguments which reveal Japan’s colonialism, even in cases where explicit formal declarations of colonialism are absent. While some may argue that it is more accurate to assert that Japan engaged in formal militarism, expansionism and imperialism instead of outright colonialism, I think that the conception of a Japanese informal “colonial empire” (as described by Peattie 1984 and Duus 1989) is more adequate. Such a construct allows me to connect military graves to a wider range of non-military individuals whose remains lie buried in places that were either settlements founded by migrant workers, spheres of operation for Japanese military occupation, or imperialist expansion. Hence, one can find at these sites the remains or gravestones of laborers, sailors, prostitutes, bureaucrats, merchants, artists, and even pets, all who were part, whether willingly or unwillingly, of Japan’s imperialist program. At these noncombatants’ final resting places, the additional inclusion of gravestones, monuments and cenotaphs dedicated to soldiers who died in action interplays with the specialized cemeteries for the war dead to create a holistic sociological image of the human toll involved in the creation/building of a regional empire, a global war and the empire’s apotheosis.

A note about the terminology used throughout this essay is necessary before moving ahead: it is important to observe that for the Japanese, the term “war dead” is not a monolithic construct, resulting in a variety of denominations for cemeteries and other sites of memory (some of which have already been introduced above). While in the West, the term “war dead” instantaneously conjures images of civilians or soldiers killed as a result of armed conflict, there is an etymological specificity between various Japanese terms that correspond to the concept of ‘war dead.’ In this essay, I employ the more neutral term “senbotsusha” (戦没者) which refers to all victims of war, including fallen military personnel and civilians who perished not only on Japan’s mainland and in Okinawa but also in the former colonial territories of the Japanese empire as well as in Manchuria (since 1932 the puppet state of Manchukuo). There is also the term “senshisha” (戦死者) which refers to men who were mobilized for war and were killed or died from injuries or disease on / on the way to the battlefield, in preparation for battle, or on the way / after arriving back home. Meanwhile, “sentōshisha” (戦闘死者) and “senshishōsha” (戦死傷者) are specifically used for personnel who died in action and from injuries inflicted during action. Furthermore, “senshibyōsha” (戦死病者) is used specifically for those who served in a war and died from infectious, endemic and other types of diseases (Hiyama 2016). In modern times, due to the Self-Defense Forces’ (SDF) status as a “non-military” force – and due to constitutional restrictions on engaging in armed conflict – the war dead are labeled as “junshoku” (殉職), or “killed in the line of duty” (in this case, the combination of kanji compounds “martyr” (殉) and “work” (職) warrant a separate etymological discussion which is beyond the scope of this paper). These distinctions are important for they shed light on the exceptional attention conferred to the social relations involving military ranks and honors and the management of the dead during or in the aftermath of war.

Domestic Cemeteries for the War Dead – The Case of Sanadayama Cemetery

In this section, I look at the historical social, economic, and political dynamics at the site of one of the most prominent cemeteries for the war dead inside Japan, Sanadayama Army Cemetery (Sanadayama Rikugun Bochi). Built in a nondescript residential area of Osaka City’s Tennōji Ward, the cemetery contains more than 5,200 gravestones and monuments belonging to the war dead from Japan’s military engagements starting from the late nineteenth century with the Saga and Satsuma Rebellions (1874 and 1877) and continuing through the First Sino-Japanese and Russo-Japanese Wars (1894-95 and 1904-05) up to the end of the Asia-Pacific War.

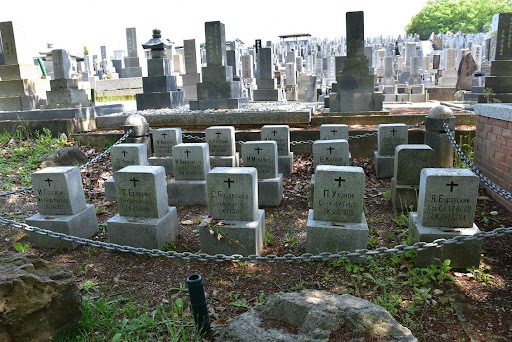

Sanadayama was established in 1871 and is the first army cemetery built in Japan. It was established based on the instructions of Ōmura Masujirō (1824-1869), the “Father of the Modern Japanese Army” (Kublin 1949). Occupying a space of almost 15,000 sq. meters, it is also the largest one in the country today. While the majority of the graves are for individuals who died in the First Sino-Japanese War, with only a handful belonging those who were killed during the Manchurian Incident (1931) and the Asia-Pacific War,4 Sanadayama offers a mirror into the proliferation and build-up of a nascent expanding empire, its military industrial and technological structures and the human cost and sacrifices made to sustain all of this. Here are the individual and collective grave markers and monuments of generals, colonels, commissioned and non-commissioned officers, soldiers, military workers and unidentified bodies, all of whom have experienced or died as a result of Japan’s world-spanning confrontations in its rise as a modern nation and empire (Fig. 1).

|

|

Fig. 1. Gravestones at Sanadayama Cemetery (photo by author) |

Among the graves, there are two monuments to German soldiers who died in captivity during World War I, after Japan attacked and occupied the German leased territory of Kiauchow in China in 1914 as part of an alliance with Great Britain. Sergeant Hermann Gol and Private Ludrich Kraft died from disease at Osaka Hospital in 1915 and 1917, respectively (Yokoyama 2003). The two soldiers belonged to a contingent of more than 4,600 German POWs that were released only in 1920, after the implementation of the Treaty of Versailles. The remains of the two Germans never left Japan; instead, a Japanese veterans’ association buried them at Sanadayama. Later, in 1931, out of respect for the dead, the carved inscription on the graves which signified “prisoner” or “captive” (furyo) was removed. In addition to German soldiers, Sanadayama also hosts the remains of six Chinese soldiers who died as a result of wounds and disease from the First Sino-Japanese War. Their designation as “captives” was also removed, possibly at the same time that the German graves were being adjusted.

The presence of these foreigners’ graves, albeit infinitesimal in the multitude of graves and monuments preserved at Sanadayama, offers a historical glance at Japan’s overseas interventions, in addition to its expansionist enemies. This is not a unique occurrence. Graves of foreigners, especially those of Russian and German soldiers who have been captured as a consequence of the Russo-Japanese War and World War I, punctuate numerous cemeteries for the war dead in many cities, including in Nagoya, Narashino and Sendai (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Nagoya Army Cemetery – Graves of Russian POWs from the Russo-Japanese War (photo by author)

In Matsuyama, at Aochi Rinsō Cemetery (Aochi Rinsō Bosho), we can find the graves of 98 Russian soldiers who died from injury or illness in captivity. In Hiroshima, at Hijiyama Army Cemetery (Hijiyama Rikugun Bochi) founded in 1872, there are the graves of seven French soldiers who died after contracting disease during the Boxer Rebellion (1899-1901) and a cenotaph dedicated to them. Their continuous preservation is an obvious intimation of Japan’s position in the geopolitical arena during a significant regional clash (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Hijiyama Army Cemetery, Hiroshima – Cenotaph and graves of French soldiers (photo by author)

At Kure Naval Cemetery (Kure Kaigun Bochi), among the 91 collective cenotaphs and 157 individual monuments, there is the grave of George Tibbins, an English sailor who died in 1907 at the age of 19 during a naval exercise near Miyajima Island. His grave’s ongoing preservation has become a symbol for the Anglo-Japanese friendship in the early twentieth century (Fig. 4). It also signifies a sense of ascending power in the world of competing empires following Japan’s victory in the Russo-Japanese War.

Fig. 4. Kure Naval Cemetery – George Tibbins’ grave (photo by author)

But as much as they reveal through graves and monuments dedicated to dead foreigners, what cemeteries conceal also has a bearing on their transnational historical background. At Sanadayama for example, one could find for a brief time the wooden markers of the graves of five U.S. soldiers who were captured and executed after their planes were shot down during fire-bombing raids on Kobe, Kure and Osaka (Yokoyama 2003, 58-61) in the spring and summer of 1945. The reason why the graves have been removed had to do with the fact that those soldiers were executed on 15 August 1945, on the same day of Emperor Hirohito’s famous radio broadcast announcing Japan’s surrender. On that day, the five soldiers were marched onto the premises of Sanadayama and forced to line up before a ditch. They were then killed by members of the Military Police for the Chūbu Military district, two by beheading and three by firing squad. During the Allied Occupation of Japan (1945-52), the incident was investigated, and the remains of the executed soldiers were dug out and sent back to the U.S. The former burial ground is now a vacant lot, but the incident was kept alive in the historical archival record at Sanadayama Cemetery. Though there are no gravestones now, the traces of this affair have been buried figuratively and literally underground and preserved in the memory of those who participated in the execution (who were eventually acquitted of war crime charges following a trial in Yokohama) before becoming an indelible part of the cemetery’s lore.5 While the physical traces have been obscured, the historical record offers a holistic view of the developments that have precipitated the cemetery’s current appearance, this being a case of circumstantial omission rather than intentional concealment.

Today, Sanadayama is managed by a non-profit organization, and the place is cleaned up and maintained by volunteers. In the first week of September 2018, Typhoon Jebi struck Japan, devastating the Kansai Region, taking lives and wreaking havoc on the national infrastructure before turning into one of the costliest storms in modern Japanese history. As soon as the weather calmed down, parts of the country kicked off what by any indication was to be a long, expensive and grievous rebuilding process. At Sanadayama, the typhoon knocked down trees and crushed or toppled a significant number of graves and monuments.

The damage caused by the typhoon, both emotional and material, was extensive and press releases observed that any formal financial alleviation for the cemetery would be slow to come due to unclear jurisdictional mapping and authority (Yoshikawa 2018). Persons with connections to the place were reportedly disheartened by the official apathy concerning a notable institution that has been around since the dawn of the Meiji Period and has become the final resting place for thousands of individuals who died for their country (Mainichi Shinbun 29 October 2018). However, instead of waiting for the official powers to make a concrete legal decision or judgment, almost 400 people, including the author of this essay, gathered here one month after the typhoon to clean the debris and to restore the weather-battered gravestones (Nihon Keizai Shinbun 15 November 2018). The participants consisted of local volunteers, family relatives or descendants of those whose remains are buried and commemorated at the site, members of Japan’s Self-Defense Forces and associations for the war bereaved. Many of the participants were middle-aged and or older, indicating a palpable distance between the younger generations and the historical significance of the place. For an entire day, those present raked the area, removed fallen trees, repaired damaged gravestones and managed to convert the cemetery to its pre-typhoon state. The work paid off and on 27 October, the cemetery opened for the yearly public memorial service attended by local politicians in addition to the family members and volunteers who partook in the initial cleaning (Fig. 5). While the attendees were relieved and content with the positive outcome of the voluntary mobilization efforts, anxieties about the future of the cemetery and the continuation of financial support needed to execute repairs and refurbish the stonework remain unabated (Asahi Shinbun 24 January 2020). For a commemorative space laden with historical and educational content which stretches across temporal and national borders, the sluggish or even absent involvement with Sanadayama by official authorities or institutions was jarring for those emotionally attached to the place. Its neglect is even more incongruous considering that nationalist politicians like Hashimoto Tōru, mayor of Osaka, regard it to be a more important commemorative space than Yasukuni (Rakuten Infoseek News 22 August 2018).

Fig. 5. Sanadayama Cemetery – Preparation for Buddhist ceremony, 27 October 2018 (photo by author)

State-owned cemeteries such as Sanadayama are built on state-owned land that is usually rented and managed by a city, ward, or prefecture. Often, the national government signs a free loan agreement with a governing body like a city in exchange for transferring the responsibility for maintenance and repairs to local authorities or non-governmental organizations (such is the case with Sanadayama). However, the price of this transfer is a lack of official financial support in cases of extreme damage like the sort which occurred in the wake of Typhoon Jebi. When such extensive damage happens, it is a dearth of bureaucratic consent over jurisdiction which prevents the allocation of necessary funding – it falls on local administrators, maintenance groups, war bereaved associations and volunteers to collect the necessary funding for repairs, conservation, and memorial services.

The issues over jurisdiction were brought up at a Diet committee meeting in 2018, where the role of national and local governments in maintaining and rebuilding military cemeteries was discussed. Most prominently, the topic of an obvious lack of legal outlining between jurisdictional responsibilities was introduced and, noticeably, it was pointed out that any documents related to management or delegation of tasks could not be found. This status was questioned in light of the fact that about half of the military cemeteries are under the control of the Ministry of Finance (Zaimushō) and are loaned to local governments free of charge, even though most of the work involved in maintaining the sites is taken up by volunteers or associations of the surviving families (197th Diet General Affairs Committee No. 4, 4 December 2018). Eventually, a budget for the repair of former military cemeteries following natural disasters was passed and expanded (Sankei News 5 January 2019). At a 2019 Diet meeting, the topic was brought up again in connection to Sanadayama, and the supervising roles for the national and local governments regarding inspections and the preservation of all domestic military cemeteries – especially after natural disasters like Typhoon Jebi – was made clearer. The lack of documentary evidence regarding jurisdiction was discussed again, pointing out the difficulties of carrying out maintenance tasks without clear legal delineation of responsibilities (198th Diet Budget Committee, 27 February 2019).

All this legal confusion points to an important outcome: an informal economy of labor and business forms at the local level, enabled by the social contrivances of memorialization and commemoration. This predicament also extends to Japanese cemeteries built overseas and the resulting social frames into which Japanese citizens, diasporic Japanese communities and, most importantly, non-Japanese Asian residents place themselves in relation to the memories of the Asia-Pacific War, be it individual or collective.

Overseas “Colonial Cemeteries” – The Case of the Japanese Cemetery in Johor Bahru

Almost 5,000 km away from Osaka, at the southern end of the Malay Peninsula, just north of Singapore, lies the city of Johor Bahru, the capital of the state of Johor in Malaysia. Here, in an isolated part of the urban sprawl, one can find a Japanese cemetery (Fig. 6) which purportedly was established in 1917 to meet the needs of the Japanese diasporic community which, at the time, was connected largely to the local rubber plantation (Shimizu 1993) and other companies looking to increase their operational foothold in Southeast Asia.

Fig. 6. Japanese Cemetery in Johor Bahru – Entrance (photo by author)

Before it was re-discovered in 1962 and restored to its present look, the cemetery was hidden by dense jungle foliage and most of its approximately 80 wooden gravestones were in a state of decay.6 The cemetery today is managed by the local Japanese Association (Nihonjinkai) founded in 1991 with the support of Japanese families and companies based in Johor. In 1995, the Japanese Embassy in Malaysia allocated a budget for graveyard maintenance and the Johor cemetery benefited from this fund. Today, the cemetery relies on donations from expatriate Japanese residents, Japanese companies, private individuals, family members of those interred there, curious itinerant visitors and those who want to pay their respects.7 But even a cursory glance reveals that resources are scarce. While the local Japanese Association organizes fund drives and employs the services of volunteers to clean up or maintain the 4,600 sq. meter space, stable material support is still lacking.

At Johor Bahru – and, similarly, in the other 33 known Japanese cemeteries in Malaysia – one can find the remains of Japanese nationals that had been at the heart of Japan’s infiltration of Southeast Asia: immigrant laborers and white-collar workers along with their families. But one can also find, for example, the communal graves of army captain Osawa Taro and warrant officer Nagata Yasuo who were killed in action during the invasion of Malaya in 1942. Most noticeable is the battlefield memorial (senseki kinenhi) built by general Yamashita Tomoyuki (1885-1946), known as the “Tiger of Malaya,” who famously led the invasion of Malaya and the capture of Singapore and ended up being tried and executed for war crimes after the end of the war. The monument was erected in 1942 to commemorate the more than 3,000 Japanese soldiers who died during combat, but it went missing sometime in June of 1945. In 1982, it was discovered broken and buried on a beach. A year later, with permission from the state government, it was installed in the Johor Cemetery where it stands to this day (Fig 7). Together, the monuments and graves contained in this cemetery provide the visitor with a wide-ranging historical foundation of Japan’s involvement in the region and the resulting human toll (on the Japanese side). The monuments and grave markers reveal an assembly of people – company men, laborers, soldiers, prostitutes – whose peregrinations and vital contributions to the expansion of the Japanese Empire have become historically entrenched.

Fig. 7. Japanese Cemetery in Johor Bahru – the Yamashita Battlefield Memorial found in 1982 (photo by author)

This being a Japanese cemetery dedicated to the Japanese dead, the graves of local Malayan people who endured exploitation and even death under Japanese occupation are patently absent. However, only a short walk away from this site, a separate monument was built by the state of Johor, which is dedicated to the victims of systematic massacres of locals known as “sook ching,” a term variously translated as “purge through purification” or “purge through elimination” (Melber 2019 and Blackburn 2000) during the Japanese occupation of Malaya (1942-45). The monument is a mass grave for more than 2,000 people killed between February 25 and March 31, 1942, and it is one of more than a dozen similar memorials erected throughout the Johor state that commemorate Japanese atrocities (Lim Pui Huen 2000).

What little or tendential reference exists at these Japanese cemeteries regarding the victims of Japan’s military aggression is synopsized in inscriptions on a few memorial towers (ireitō). For example, an ireitō erected in 1978 in the Japanese Cemetery in Kuala Lumpur (Fig. 8) is dedicated to the consolation of the spirits of the dead, but not just those of the Japanese.

Fig. 8. Japanese Cemetery in Kuala Lumpur – Ireitō (photo by author)

The inscription on the side reads in English “We Japanese mourn for the spirits of the citizens and soldiers of all countries who fell in WWII [sic] and wish peace and prosperity to the Malaysian Federation.”8 While it falls short of admitting Japan’s responsibility for the war, the monument is just one of many that try to appease the local or regional sensitivities vis-à-vis historical memory and address Japan’s role in the history of the place. Significantly, this monument was built by former members of the 11th Infantry Regiment who participated in the Malayan campaign in 1941, and then managed the occupation of the country.9

At the Johor Bahru cemetery, however, a memorial dedicated to the Japanese war dead discordantly engraved with the English phrase, “In memory of Noble Comrades” (Fig. 9) has no reference to Malay victims similar to the monument at Kuala Lumpur. Furthermore, its Japanese denomination – shōkonhi (Memorial to the Loyal War Dead) – uncannily calls to mind the prewar vocabulary of the “loyal war dead.” Pre-1945, memorials and shrines were often named shōkonhi or shōkonsha, and only after the end of the war, this loaded term fell out of fashion, with ireihi becoming the dominant term used to name memorials dedicated to the “war dead” (Kobayashi and Terunuma 1969). Pre-war shōkonhi commemorated victory in battle and the return of triumphant soldiers but also galvanized soldiers into taking an active part on the battlefield. Because the Japanese community in Kuala Lumpur chose to use this particular term and, thus, revive the prewar ideology of beautifying death in battle, the appearance of this monument in a Japanese cemetery built in a former wartime colony must be considered highly problematic.

Fig. 9. Japanese Cemetery in Johor Bahru – Shōkonhi (Memorial to the Loyal war dead) (photo by author)

The naming might have to do with the popularity of war-beautifying views by the Japanese elites (Saaler 2016) rather than among the local organizations. Notably, the Japanese cemeteries and memorials in Malaysia have not always developed through ‘bottom-up’ efforts; rather, the assistance of the Japanese government was needed to secure local cooperation. The Japanese Embassy in Malaysia has supported the relocation of graves and monuments dispersed throughout Johor and even built a monument to commemorate the deepening relations between Malaysia and Japan and pay tribute to the memory and the hardships of fallen soldiers. However, there is still no centralized organization responsible for maintaining and preserving this type of commemorative site similar to those of the United Kingdom or Germany. Monuments and graves sometimes are abandoned to the passage of time and the elements. When official involvement occurs, it is often connected with the erection of cenotaphs. But even these are funded through the financial contributions of donors with a strong connection to the place, such as corporations and expats. Large overseas Japanese cemeteries like the ones in Singapore and Kuala Lumpur do not lack this kind of support. The strain is more perceptible at smaller cemeteries, like the ones in Johor Bahru, Malacca, Ipoh and George Town. Nevertheless, the presence of these cemeteries does leave an imprint on the local economy through the hiring of local residents who clean and administer the sites in the absence of Japanese authorities and through the impact of overseas commemorative tours and visitors.10

The Johor cemetery is a minor one in the informal network of similar sites scattered throughout Southeast Asia, especially when one compares it to the more distinguished, well-funded and well-maintained Japanese cemeteries in Singapore and Kuala Lumpur. While it receives visitors, these are mainly confined to surviving family, members of the Japanese Association and curious travelers. By contrast, the Kuala Lumpur and Singapore Cemeteries are visited by organized tours from the Japanese mainland and even diplomats and politicians.11 For example, Abe Akie, the wife of former Prime Minister Abe Shinzō, visited the Kuala Lumpur cemetery in 2015; members of the House of Representatives, including Takaichi Sanae, have also paid visits and offered flowers. However, even in the absence of these extravagances, the Johor Bahru site continues to maintain its unique historical flavor as one of many sites spread out throughout Malaysia carrying a loaded past carved in stone – and interred in the ground.

Conclusion

Cemeteries fit the description of “mnemonic sites” (Fujitani 1996) or vehicles of meaning that construct memories of a certain past. The symbolism of mnemonic sites – whether they are cemeteries, monuments or simple stones inscribed with a commemorative message, a name or a letter – does not remain static over time and their significance is not uniform in trans-cultural contexts. However, the continuous presence of these cemeteries and the markers they contain (gravestones, cenotaphs, memorials, etc.) augments a country’s commemorative topography, and amplifies the local, national or international imaginations of those who interact with these spaces. The “user perspective” (Francis et al. 2000), which explores who visits cemeteries and why, shows us that these sites or spaces of memory preserve important, largely unrecognized, and undervalued implications in terms of historical and political dimensions utilized in the integration of personal, familial and community-based dynamics, be they local, national or international. Whether there is a group of former colonialists buried in a cemetery located in a former colony, or a cenotaph which commemorates the dead who were directly or indirectly involved in the colonizing project through violence or other means, what scholars have termed the “user perspective” is imperative in order to make sense of these historical narratives preserved in wood, stone or marble or buried underground.

When and why do people visit these cemeteries? How often do they visit? Who visits and who is visited? There is no one general answer to these ethnographic queries; rather, each site at different points in time reveals the interplay between regional, economic and political interests subsuming the personal connections.12 Answering those questions would be undoubtedly helpful in disclosing the levels of community support and the extent of the conviction behind the staunchness to keep these spaces open to visitors. However, it is more important to start incorporating these ‘vernacular’ cemeteries into the debates about Japanese memorials for the war dead in order to eventually assign them to a more central position which is currently occupied almost exclusively by Yasukuni Shrine. The “user perspective” in this case should revolve around questions such as: How might visitors understand these cemeteries? Why might they visit them? Who visits and maintains them? While not exhaustive, these questions delineate the boundaries of physical commemorative remainders of armed conflict and colonialism; at the same time, they bring into focus the emergent conversation across borders in a manner geared towards a better understanding of a shared historical past between aggressor and victim. I have chosen the two case studies in order to shed light on the larger conciliatory possibilities contained by cemeteries for the war dead as sites of history, memory and commemoration. Whether built domestically and infused with the long history of Japan’s pursuit of military strength and modernization to match its Western models from the Meiji era onwards (like Sanadayama) or built and (still-)maintained overseas out of the necessity to host and commemorate the human toll caused by its expansionist schemes or to simply serve diasporic communities (like the Johor Bahru cemetery), these sites occupy unique and important ideological and material positions in Japan’s dialogue with its neighbors but also with its past, present and future. Bereft of the fame and controversial image accorded to Yasukuni, these sites may strike one as essentially unimportant, especially as they seem to lack the prestige and public attention that similar sites are accorded in the West. When compared to Chidorigafuchi, they are quite visibly on the periphery of mainstream, conventional dialogue concerning Japan’s remembrance of its war dead, even though these sites carry out their own commemorative events, albeit on a smaller scale. They also grapple with the challenge of being sufficiently and securely funded or kept in good condition. And yet their existence and continuous preservation articulates Japan’s position at the heart of historical global events, even when such events are marked by tragedy and death.

The memories conserved or manufactured in these spaces relate to a historical past that is sometimes unsettling, sometimes transgressive, sometimes controversial, sometimes benign, sometimes reconciliatory and healing. This wide-raging affective quality is the result of a combination of factors anchored in the importance of the deceased and the embedded historical narratives that the deceased communicate through the organization, preservation, and maintenance of these sites of final rest. Above and beyond Yasukuni, the bodies or ashes interred in these sites – especially those reposed in a ‘colonial cemetery’ –perform a reconciliatory function that is harder to politicize due to their actual materiality. Right-wing Japanese politicians may try to instrumentalize these sites in order to instill a sense of patriotism or nationalism at home but their actual distance from home, as well as their location in a foreign land that fought against Japan’s expansionist ambitions thwart their politicization.

Because they have not been removed by a resenting local public, and because they are tended for by an expat community often with the help of locals, these sites are equipped with a more comprehensively-historic sense of national narrative, one that showcases loss and hope, tragedy and fortune, enmity and goodwill, past, present and future.13 Finally, the global connections presumed by these sites – in the form of large numbers of soldiers and non-combatant citizens abandoned in foreign places, away from their hometown (furusato) by the entity that was assembled from a now-vanished empire, a terminated occupation power and a defeated military force – transform these sites into transnational spaces of mourning. This is also the case with other former empires, such as Germany, Russia or Great Britain, whose dead nourish the soils of Japanese cemeteries as mentioned above. Empires by definition are transnational rather than just national: this particular condition continues to resonate from beyond the grave. Other instances of this transnational narrative can also be found domestically, in places like Ryōzen Kannon which collects the individual names of allied personnel who perished in the territories under Japanese jurisdiction during the Asia-Pacific War, alongside urns filled with soil garnered from military cemeteries from all over the world (see Milne and Moreton in this special issue); or they can be found in the numerous graves and monuments for foreigners, most of whom were enemies, dotting the country. It is difficult to reconcile this commemorative vision – fragmented throughout the country and outside of it – with the hegemonic sway of Yasukuni, but the potential exists, and it is one which does not need to incur the wrath of Japan’s neighbors or the West. Sanadayama and the Japanese Cemetery at Johor Bahru, as this paper has established, are positioned well within that vision.

References

Atlas Obscura. 2 June 2020. “Why Singapore is Digging Up Its Few Remaining Cemeteries.” [Accessed 19 November 2021].

Baxter, Joshua. 2015. “Envisioning Tokyo’s Acropolis: Nagano Uheiji’s 1907 Blueprint for Kudan Hill and the Political Economy of Yasukuni Shrine.” The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus Vol. 13, Issue 38, No. 3, 28 September. [Accessed 19 November 2021].

Beaumont, Joan. 2016. “The Diplomacy of Extra-Territorial Heritage: The Kokoda Track, Papua New Guinea.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 22 (5): 355-367.

Blackburn, Kevin. 2000. “The Collective Memory of the Sook Ching Massacre and the Creation of the Civilian War Memorial of Singapore.” Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 73 (2): 71-90.

Blackburn, Kevin. 2007. “Heritage Site, War Memorial and Tourist Stop: The Japanese Cemetery of Singapore, 1891-2005.” Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 80 (1): 17-39.

Blackburn, Kevin, and Nakano, Ryoko. 2018. “Memory of the Japanese Occupation and Nation-Building in Southeast Asia.” In Daniel Schumacher and Stephanie Yeo (eds.) Exhibiting the Fall of Singapore: Close Readings of a Global Event. Singapore: National Museum of Singapore. 26-44.

Breen, John (ed.). 2008. Yasukuni, the War Dead, and the Struggle for Japan’s Past. New York: Columbia University Press.

Connerton, Paul. 1989. How Societies Remember. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Coser, L. A. 1992. “Introduction.” In Maurice Halbwachs (ed.) On Collective Memory. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 1-36.

Duus, Peter. 1989. “Introduction – Japan’s Informal Empire in China, 1895-1937: An Overview.” In Peter Duus, Ramon H. Myers, and Mark R. Peattie (eds.) The Japanese Informal Empire in China, 1895-1937. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. xi-xxix.

Francis, Doris, Kellaher, Leonie, and Neophytou, Georgina. 2000. “Sustaining Cemeteries: The User Perspective.” Mortality 5 (1): 34-52.

Fujitani, Takashi. 1996. Splendid Monarchy: Power and Pageantry in Modern Japan, Berkeley: University of California Press.

Graham, Brian. 2011. “Sharing Space? Geography and Politics in Post-conflict Northern Ireland.” In Peter Meusburger, Michael Heffernan, and Edgar Wunder (eds.) Cultural Memories: The Geographical Point of View. New York: Springer. 87-100.

Harada, Keiichi. 2002. “Gun’yō bochi no sengoshi: Hen’yō to iji wo megutte.” Bukkyo University Journal of the Faculty of Letters 86: 27-41.

Harada, Keiichi. 2013. Heishi wa doko e itta: Gun’yō bochi to kokumin kokka. Tokyo: Yūshisha.

Hiyama, Yukio. 2016. “Nihon no senbotsusha irei to sensō kinenhi no keifu: Seinan sensō senshisha irei.” Chūkyōhōgaku 50 (3-4): 319-320.

Hock, David K. W. (ed.). 2007. Legacies of World War II in South and East Asia. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

Hotta, Eri. 2007. Pan-Asianism and Japan’s War 1931-1945. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Husain, Sarkawi B. 2015. “Chinese Cemeteries as a Symbol of Sacred Space Control, Conflict, and Negotiation.” In Freek Colombijn (ed.). Cars, Conduits, and Kampongs: The Modernization of the Indonesian City, 1920-1960. Leiden: Brill. 323-340.

Jager, Sheila Miyoshi, and Mitter, Rana (eds.). 2007. Ruptured Histories: War, Memory, and the Post-Cold War in Asia. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

Juneja, Monica. 2009. “Architectural Memory Between Representation and Practice: Rethinking Pierre Nora’s Les Lieux de Mémoire.” In Indra Sengupta-Frey (ed). Revisiting Sites of Memory: New Perspectives on the British Empire, London: Bulletin of the German Historical Institute (Supplement 1). 11-6.

Kingston, Jeff. 2007. “Awkward Talisman: War Memory, Reconciliation and Yasukuni.” East Asia 24 (3): 295-318.

Kobayashi, Kenzo, and Terunuma, Yoshifumi. 1969. Shōkonsha seiritsu no kenkyū. Tōkyō: Kinseisha.

Kublin, Hyman. 1949. “The ‘Modern’ Army of Early Meiji Japan.” The Far Eastern Quarterly 9 (1): 27-28.

Laqueur, Thomas W. 2015. The Work of the Dead: A Cultural History of Mortal Remains. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Lemay, Kate Clarke. 2018. “The Construction of Transnational Remembrance in the War Cemeteries of the Twentieth Century.” International Journal of Military History and Historiography 38: 159-169.

Lim Pui Huen, Patricia. 2000. “War and Ambivalence: Monuments in Johor.” In Huen, P. Lim Pui and Wong, Diana (eds). War and Memory in Malaysia and Singapore. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. 139-59.

Mainichi Shinbun. 29 October 2018. “Kyū rikugun bochi’ no hoshū futan: kuni to shi ga tsunahiki.“

Mareishia kakushi nihonjin-kai hen. 1999. Mareishia no nihonjin bochi oyobi bohi. Zai Mareishia Nihon Taishikan.

McDonald, Kate. 2017. Placing Empire: Travel and the Social Imagination in Imperial Japan, Oakland: University of California Press.

Melber, Takuma. 2019. “The Impact of the ‘China Experience’ on Japanese Warfare in Malaya and Singapore.” In Miguel Alonso, Alan Kramer, and Javier Rodrigo (eds.). In Fascist Warfare, 1922-1945: Aggression, Occupation, Annihilation. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. 169-193.

Mosse, George L. 1990. Fallen Soldiers: Reshaping the Memory of the World Wars. New York: Oxford University Press.

Nichanian, Marc. 2016. “The Death of the Witness; or, The Persistence of the Differend.” In Claudio Fogu, Wulf Kansteiner and Todd Presner (eds.). Probing the Ethics of Holocaust Culture. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. 141-166.

Nihon Keizai Shinbun. 15 November 2018. “Ōsaka no kyū Sanadayama rikugun bochi taifū de kōhai susumu, kanri ni kadai.“

Nora, Pierre. 1989. “Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Mémoire.” Representations 26: 7-24.

Ōkuma, Takashi. 24 January 2020. “Boseki naoshi, ‘ikita akashi’ nokosu Ōsaka no rikugun bochi de hatsu kōji.” Asahi Shinbun.

197th Diet General Affairs Committee No. 4. 4 December 2018. [Accessed 19 November 2021].

198th Diet Budget Committee. 27 February 2019. [Accessed 19 November 2021].

Orr, James J. 2001. The Victim as Hero: Ideologies of Peace and National Identity in Postwar Japan. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

Peattie, Mark R. 1984. “Introduction.” In Ramon H. Meyers and Mark R. Peattie (eds.) The Japanese Colonial Empire. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. 1-52.

Rakuten Infoseek News. 22 August 2018. Hashimoto Tōru “Yasukunijinja sanpai yori mo daijina koto.” [Accessed 19 November 2021].

Rose, Caroline. 2007. “Stalemate: The Yasukuni Shrine Problem in Sino-Japanese Relations.” In John Breen (ed.). Yasukuni, the War Dead and the Struggle for Japan’s Past. London: Hurst Publishers Ltd. 23-46.

Saaler, Sven. 2005. Politics, Memory and Public Opinion: The History Textbook Controversy and Japanese Society. München: Iudicium Verlag.

Saaler, Sven. 2016. “Nationalism and History in Contemporary Japan.” In Asian Nationalisms Reconsidered, edited by Jeff Kingston. Abingdon: Routledge.

Saaler, Sven, and Schwentker, Wolfgang (eds.). 2008. The Power of Memory in Modern Japan. Folkestone: Global Oriental.

Sankei News. 5 January 2019. “Seifu, kyūgun’yō bochi hoshū e yosan kakujū: rōkyū-ka ya hisai de 5-nen 5 oku-en.“

Shimizu, Hajime. 1987. “Nanshin-ron: Its Turning Point in World War I.” The Developing Economies 26 (4): 386-402.

Shimizu, Hajime. 1993. “The Patterns of Japanese Economic Penetration of Prewar Singapore and Malaya.” In Saya Shiraishi and Takashi Shiraishi (eds.). The Japanese in Colonial Southeast Asia. Ithaka: Cornell University Southeast Asia Program. 63-88.

Shin, Gi-Wook, Park, Soon-Won, and Yang, Daqing (eds.). 2007. Rethinking Historical Injustice and Reconciliation in Northeast Asia: The Korean Experience. Abingdon: Routledge.

Takahashi, Tetsuya. 2005. Yasukuni mondai. Tōkyō: Chikuma Shobō.

Takenaka, Akiko. 2015. Yasukuni Shrine: History, Memory, and Japan’s Unending Postwar. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2015.

Trefalt, Beatrice. 2002. “War, Commemoration and National Identity in Modern Japan, 1868-1975.” In Sandra Wilson (ed.). Nation and Nationalism in Japan. Abingdon: Routledge Curzon. 115-134.

Yamabe, Masahiko. 2003. “Chōsa kenkyū katsudō hōkoku zenkoku rikukaigun bochi ichiran.” Bulletin of the National Museum of Japanese History 102: 611-696.

Yokoyama Atsuo. 2003. “Kyū Sanadayama rikugun bochi hensen-shi.” Kokuritsu Bulletin of the National Museum of Japanese History 102: 41-43.

Yoshikawa, Takashi. 25 September 2018. “Ishibumi no 7-wari ni hibi, areru rikugun bochi hoshū wa oshitsuke ai ni.” Asahi Shinbun.

Notes

About these efforts, alongside commemorative events organized by the Ministry, see the main website. See also Trefalt 2002.

Jean Beaumont uses another term for this set of circumstances: “extra-territorial heritage” (2016) which draws parallels to the episodes covered by Alison Starr and Beatrice Trefalt that are included in this special issue.

See Alison Starr’s paper in this issue which investigates the Japanese memorial cemetery at Cowra in Australia.

For historical details, see the Johor Japanese Association’s main website. For a meticulous overview of the 33 Japanese cemeteries in Malaysia from which most of this historical information is collected, see Mareishia kakushi nihonjin-kai hen, 1999.

The English translation uses the term “WWII” which is most familiar to Westerners; however, the original Japanese inscription uses the alternative term “the Pacific War” (Taiheiyō sensō) which is popularly used inside Japan but excludes theaters of war in Asia, rendering its use somewhat tendentious (Hotta 2007).

At the same cemetery in Kuala Lumpur, another monument was recently built, a cenotaph (ireihi) completed in 2018 with financial support from the Japanese government. I was able to track its construction throughout two different trips I made to the site. The inscription reads: “In the memory of our ancestors (senjin) resting here under the ground and praying for lasting peace, we build this monument with the support of the [Japanese] Embassy in Malaysia.”

As a member of the Johor Japanese Association – otherwise known as the Japan Club of Johor – one can receive discounts at various local restaurants (the majority non-Japanese). The Association also sells souvenirs.

For the significance of tourism engendered by these sites, especially the Singaporean case, see Blackburn 2007.

On Japan’s involvement in the economic development of Southeast Asia and the memorializing project of preserving old colonialist Japanese sites see Blackburn and Nakano (2018). On how Singapore and Indonesia have preserved old Japanese cemeteries while demolishing local, Chinese ones, see Atlas Obscura (June 2, 2020, also Husain 2015).

This is, of course, different in China and South Korea where old wartime enmities still exist or are still fought in courts of law.