Abstract: The year 2022 marks the fiftieth anniversary of Okinawa’s reversion to Japan. This article examines the Japan Civil Liberties Union’s 1955 solidarity activism on occupied Okinawa, which generated Japanese civil society’s first awakening to the “Okinawa problem.” The Asahi Shinbun’s front-page article on the organization’s publication “Human Rights Problems in Okinawa” and its follow-up coverage triggered public debate influencing Japan/U.S. official policies on Okinawa. Drawing on archival evidence, the article illuminates the contested nature of Japanese activism caught between Cold War Asia and decolonizing Asia. It argues that the 1955 activist movement shaped the subsequent trajectory of Japanese engagement with the “Okinawa problem.”

Keywords: Okinawa, Japan, the United States, the Third World, American military bases, human rights, decolonization, race, solidarity activism

Introduction

In 1954, a group of legal professionals affiliated with the Japan Civil Liberties Union (JCLU) undertook a ten-month investigation of human rights violations in Okinawa under U.S. occupation. Japan had regained its national sovereignty two years earlier under the condition that Okinawa would remain militarily occupied under the San Francisco Peace Treaty and Japan would accept continued U.S. basing under the Japan-U.S. Security treaty. The investigation resulted in a report entitled “Human Rights Problems in Okinawa (沖縄における人権問題)” and was given extensive coverage in Japan’s major daily newspaper, the Asahi Shinbun. This ignited a nation-wide public outcry and inaugurated a dynamic interplay between Japanese civic activism on Okinawa and U.S. diplomacy in Asia that prepared the way for the eventual reversion of Okinawa to Japan in 1972. In the following I highlight the mid-1950s as a pivotal moment in the triangular relationship among Okinawa, Japan, and the United States by linking the rising tide of neutralism in post-colonial Asia with the decline of Japanese public support for the Japan-U.S. security relationship and Japan’s reemergence in Asia. I thereby aim to contribute to the history of Japanese attitudes toward Okinawa, the development of solidarity activism between the two, and the triangular Okinawa-Japan-U.S. relationship more broadly.

Japanese scholarship has emphasized how much the “1955 awakening” was driven by the convergence of a growing nationalism in national politics and popular calls for the integrity of territorial sovereignty. On the official level, the Hatoyama administration (1954-1956) called for the normalization of Japan’s relations with the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China (PRC), highlighting a departure from the Yoshida administration’s U.S.-centric diplomacy.1 Serving under Hatoyama, Foreign Minister Shigemitsu Mamoru requested the reversion of Okinawa and “sympathetic treatment” of locals during his meeting with Secretary of State John Foster Dulles in August 1955, seven months after the “Asahi coverage.” However, Dulles flatly rejected the request. To be sure, the Hatoyama administration’s diplomatic priority at the time lay in improving Japan’s relations with the Soviet Union rather than improving Okinawa’s status.2 And as Oguma Eiji has noted, there was in fact little understanding of, or inter-ministerial debate over, such fundamental issues as Okinawan nationality.3

More consequential than a shared nationalism among politicians and grassroots activists was the emergence of Japanese solidarity activism with Okinawa across political lines. Arasaki Moriteru recognized the Asahi Shinbun’s initiative in generating a public debate without prior impetus from political parties and urging the government to act on behalf of the islanders on the basis of Japan’s “residual sovereignty” over Okinawa.4 Sakurazawa Makoto, analyzing media reports on Okinawa before and immediately after 1955, concluded that the Japanese public’s earlier neglect of the “Okinawa problem” was the product of an overly celebratory image of American democracy. In his assessment, 1955 marked a noticeable decline in the public image of American democracy in postwar Japan.5 Oguma Eiji contended that in the 1950s, Japanese progressives increasingly likened the division between Okinawa and the subservience of Japan to the United States to the struggle for national liberation on the part of Afro-Asian countries.6 The underlying political context was a reevaluation of the success of the Chinese Communist Revolution by Japanese progressives reinforced by growing “anti-Americanism.” The 1950s saw a notable shift from the late 1940s when many intellectuals had been preoccupied with the contrast between “western modernity” and Japan’s wartime authoritarianism, and as Oguma noted, applauded the former.7

Scholars of Okinawa, meanwhile, have acknowledged the link between the so-called “Asahi coverage (朝日報道)” of the JCLU report and occupied Okinawans’ mobilization against the American military in 1955 and 1956. Arasaki Moriteru called it “the arrival of a million auxiliary forces,” underscoring the Asahi Shinbun’s role in invigorating Okinawans’ struggle against the American military’s confiscation of land and shifting their political consciousness towards Japanese identity.8 It set the preconditions for the formation of a popular protest movement that exploded in response to the Yumiko-chan Incident (由美子ちゃん事件), the rape murder of a local preschool girl by a GI in the fall of 1955. This suprapartisan protest movement paved the way to Okinawans’ “island-wide struggle (島ぐるみ闘争)” against the U.S. military’s land policy.9

On the global level, JCLU activism resonated with Afro-Asian countries’ calls for decolonization, dramatically symbolized by the First Afro-Asian Conference (Bandung Conference) of April 1955. Amid the rise of the public debate over Okinawa, the author of the JCLU report Ushitomi Toshitaka (潮見俊隆) appealed for international inquiries into human rights violations committed by the American military at the Conference of Asian Lawyers in Calcutta, India. The meeting took place three months before the Bandung Conference. Although reversion to Japan was not yet a collective political agenda in mid-1950s Okinawa, the media coverage of Japanese and Afro-Asian solidarity eventually inspired the first Okinawan mass popular uprising against American military injustices in the spirit of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) that year.10 For the first time in the decade since Japan’s defeat and occupation, emergent Japanese solidarity activism with Okinawa demonstrated the possibility of post-occupation Japan’s popular protest against the U.S. occupation of Okinawa and the development of solidarity movements with the decolonizing Third World.

In July 1956, 12,000 people attended the “National Mass Rally to Solve the Okinawa Problem” (沖縄問題解決国民総決起大会) in Tokyo, and similar demonstrations followed across the archipelago. Against the backdrop of growing public attention to Japan’s “lost territories” in the aftermath of World War II—the Chishima Islands (Southern Kuril Islands) then under the control of the Soviet Union and the Ryukyu Islands then occupied by the United States—Japanese conservatives and progressives collectively demanded U.S. authorities’ respect for Okinawans’ rights to their land seized by the military. The lingering national question of the Japan-U.S. security relationship—the American military presence in particular—dissolved suprapartisan platforms, which had been forged on the basis of nationalist or/and universalist positioning toward the “Okinawa problem.” The united front between the right and left crumbled as early as 1956.11

Absent in the historiography is an analysis of the JCLU and the political dynamism that revolved around it, which is key to further exploring the 1955 Japanese engagement with the “Okinawa problem” and better conceptualizing solidarity activism. Scholars of international relations such as Watanabe Akio, Kōno Yasuko, and John Swenson-Wright recognized the domestic and international implications of the JCLU report for long-term U.S. policy on Okinawa.12 Yet no scholar has shown how the JCLU report came into existence, how it was perceived by U.S. policy elites, and how the JCLU responded to U.S. countermeasures amidst the Japanese awakening to the “Okinawa problem.”

My reading of the JCLU report suggests that Okinawans’ ambiguous and unique legal status propelled them to mobilize popular human rights activism under the banner of the UDHR as early as the mid-1950s. According to Samuel Moyn’s well-known thesis, what we know as “human rights”—a contemporary concept understood as the international protection of individual rights—did not exert substantial influence on international society until the 1970s, because human rights activism before then, he argued, had been couched in struggles for national self-determination.13 Okinawans, however, did not cry for “self-determination,” “autonomy,” or “reversion to Japan” in the 1950s in their collective resistance to U.S. Cold War policy. Rather Okinawans demanded the right to life and equality before the law for those living under military occupation, as well as equality with people who enjoyed national sovereignty.14 In Japan, a grassroots organization named Nihon seinen dantai kyōgikai (日本青年団体協議会) played a leading role in spreading participatory solidarity activism with the language of universal values such as human rights in the 1950s, according to Ono Yuriko.15 Yet neither this organization nor the JCLU succeeded in popularizing human rights activism as Okinawans did. To put it differently, while human rights activism became a driving force for galvanizing suprapartisan fronts in U.S.-occupied Okinawa, it did not take root in post-occupation Japan.

To shed new light on the 1955 Japanese awakening to the “Okinawa problem,” I examine the interplay between the JCLU solidarity activism and responses of U.S. policy elites. I draw on a wide array of sources—declassified U.S. diplomatic sources (both civilian and military), newspapers, magazines, legal journals, and publications of grassroots organizations such as the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and the Okinawa Human Rights Association (沖縄人権協会)—to analyze how Cold War binarism and the growing tides of neutralism in Asia played out in the JCLU and other related actors’ engagement with the “Okinawa problem.” The historical context that gave birth to the JCLU report, its political impact in and beyond Japan, and its legacy for the post-1955 Okinawa-Japan-U.S. relationship are central to my analysis.

I conclude that the mid-1950s Japanese solidarity activism on Okinawa reflected the tension between neutralism and continued military reliance on the United States on the eve of the Bandung Conference. The JCLU’s agency must be recognized to identify the roots of Japanese solidarity activism with Okinawa. At the same time, JCLU ambivalence toward the San Francisco System and ACLU pressure on the U.S. government based on the premise of accepting the U.S. military presence on Okinawa also require attention.

Local and Global Conjunctures: How the JCLU Report Came into Existence

Before 1955, most Japanese treated U.S.-occupied Okinawa as a “forgotten island,” as Times Magazine reporter Frank Gibney initially phrased it in 1949.16 Indeed, Japanese Diet approval of the U.S. jurisdictional separation of the Ryukyus from Japan without the islanders’ consent implicitly assumed and affirmed a separate identity. During the negotiations on the Japan-U.S. in 1950-1951, the Liberal Party, the Democratic Party, and the Socialist Party demanded the reversion of the Ryukyu Islands (as well as of the Chishima Islands and the Ogasawara Islands) to varying degrees; an exception was the Communist Party, which asserted Okinawans’ right to determine their own fate, including independence from Japan.17 In 1951, over eighty percent of the Ryukyuan population called for immediate reversion.18 W. J. Sebald, Chief of Diplomatic Section of the Office of U.S. Political Advisor in Japan, concluded: “While many Japanese [were] undoubtedly disappointed over evident failure [to] obtain concession [of the] return [of] former overseas territories [apparently including the above islands], this feeling appears outweighed by gratification over proposed security agreements and clear-cut assurances that US will not permit power vacuum in post-treaty Japan.”19

Against the backdrop of the rise of communist forces in East Asia, notably in China, Vietnam, and North Korea, the so-called San Francisco System took effect. This refers to the combination of the San Francisco Peace Treaty, the first Japan-U.S. Security Treaty, as well as an executive agreement stipulating detailed arrangements for continued U.S. basing in Japan (Japan-U.S. Administrative Agreement). The system guaranteed a “generous” peace settlement with Japan on condition that it accept a “separate peace” only with the countries which endorsed U.S. Cold War policy and the continued deployment of American troops in post-occupation Japan and U.S.-occupied Okinawa, a deployment that would subsequently expand and continue to the present.20

Okinawa’s legal status was determined in international law via Article 3 of the Peace Treaty, which stated:

Japan will concur in any proposal of the United States to the United Nations to place under its trusteeship system, with the United States as the sole administering authority, Nansei Shoto south of 29 degree north latitude (including the Ryukyu Islands and the Daito Islands), Nanpo Shoto south of Sofu Gan (including the Bonin Islands, Rosario Island and the Volcano Islands) and Parece Vela and Marcus Island. Pending the making of such a proposal and affirmative action thereon, the United States will have the right to exercise all and any powers of administration, legislation and jurisdiction over the territory and inhabitants of these islands, including their territorial waters.21

Indeed, such a “proposal” was forthcoming from the Truman administration, and the Yoshida administration accepted, if not willingly, the continued U.S. military occupation of Okinawa. In the end, U.S. authorities did not invoke the UN trusteeship system, finalizing their strategic position that U.S. recognition of Japan’s “residual sovereignty” over the Ryukyu Islands without UN involvement. This formula, which retained U.S. control over the Ryukyus following the end of the U.S. occupation of Japan allowed the U.S. to avoid interference from the UN.22 Postwar American national security ideology served to underpin the global network of American military bases—of which the San Francisco System and the Okinwan bases were a crucial part. To borrow the words of Michael Hogan’s classic work on the postwar U.S. national security state, it “framed the Cold War discourse in a system of symbolic representation that defined America’s national identity by reference to an un-American ‘other,’ usually the Soviet Union, Nazi Germany, or some other totalitarian power.”23 In the Japanese case, this was manifested in the Red Purge in the late-1940s and early-1950s, the final years of the formal U.S. occupation of Japan.

Concurrently on the global stage, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) adopted at the UN General Assembly in 1948 advanced a multilateralist and social democratic definition of “human rights,” centered on the equality of all human beings and their political, economic, social, cultural, and religious rights.24 What could be defined as universal human rights became a subject of global ideological battles at the dawn of the Cold War and postwar decolonization. Whereas the Truman administration emphasized liberal democratic principles of rights (civil and political rights premised on the protection of individual freedoms from the state), representatives from the Soviet bloc and postcolonial states in Asia and Africa prioritized a wide range of social and economic rights based on its interpretation of Marxist anti-colonial and class theories. Within the United States, there also existed the tension between Franklin D. Roosevelt’s widow Eleanor Roosevelt, who served as Chair of the United Nations Commission on Human Rights and represented New Dealers’ social democratic values under the Democratic administration, and Republican lawmakers led by John Foster Dulles, who resisted calls for racial equality, economic redistribution, as well as the legal enforcement of the UDHR.25 The UDHR, i.e., a product of the compromise and fusion of multilayered philosophical foundations, stood in sharp contrast to the racialized and hierarchical worldviews held by many American and Japanese policymakers and the general public alike. Despite its non-legally binding status, the UDHR, eventually supported by the Truman administration, would serve as a key referential text for rights struggles in occupied Okinawa.

By the mid-1950s, U.S. policymakers were aware of challenges to the Japan-U.S. security relationship. After Stalin’s death and the armistice of the Korean War in 1953, Washington expanded its alliance network by creating the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO) to counter Soviet and Chinese ideological influence on newly independent states in Asia and Africa. Although Japan was the first to join the U.S.-led network of alliances in East Asia, U.S. pressure for Japan’s rearmament and the permanent American military presence divided the Japanese public.26 In particular, U.S. armed forces’ immunity from local jurisdiction, secured by Article 17 (criminal jurisdiction provision) of the Japan-U.S. Administrative Agreement, gave rise to a nationwide protest movement against American extraterritoriality and severely weakened the Yoshida administration in 1952 and 1953.27 A series of anti-nuclear and anti-base protests—the Sunagawa struggle (砂川闘争) being the most prominent28—accelerated the fall of the Yoshida administration.

In 1955, Japanese diplomacy was in limbo under the leadership of Hatoyama, who pledged to depart from Yoshida’s U.S.-centric diplomacy, facilitate remilitarization, and undertake efforts to normalize Japan’s diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union and China. This political climate gave birth to the “1955 system,” under which the mergers of the Liberal and Democratic parties and the two Socialist parties came to represent postwar Japanese ideological divides over war-renouncing Article 9 of the constitution. The “Okinawa problem” did not become a central issue in the general election of February 1955 when the main focus of public debate was whether or not to revise the constitution. Yet the U.S. occupation of Okinawa bolstered all political parties’ critical stance on the existing Japan-U.S. relationship. Given the armistice of the Korean War in 1953 and the growing influence of pacifist movements opposing the revision of Article 9, the Socialist Party, including its rightwing faction, began calling for Japan to implement pacifist diplomacy and join the neutralist tide in Asia.29

Although neutralism was far from a collective political agenda in mid-1950s Okinawa, the American military faced rising local resistance during this period, in both Japan and Okinawa. Under the San Francisco System, the occupation regime in the Ryukyus consisted of a dual-administrative system, dividing functions between the United States Civil Administration of the Ryukyu Islands (USCAR) and the Government of the Ryukyu Islands (GRI). USCAR was de jure authorized to intervene in public affairs run by three branches of the GRI, thereby retaining ultimate sovereignty. Led by GRI Chief Executive Higa Shūhei (比嘉秀平), a former English teacher appointed by USCAR from the conservative Ryukyuan Democratic Party (RDP), Okinawans debated the best ways to grow the local economy, expand rights, and improve welfare. The RDP, the centrist Okinawa Socialist Mass Party (OSMP), and the leftist Okinawan People’s Party (OPP) constantly clashed over their positioning toward the American military. Yet the U.S. military’s confiscation of native land, authorized by the Land Expropriation Ordinance in 1953, galvanized a popular protest movement, fostering solidarity networks between political parties, municipal entities, and grassroots organizations. In April 1954, the GRI Legislature proclaimed “Four Principles for the Protection of Land” for its suprapartisan resistance.30 The island-wide resistance to the U.S. occupaiton regime gradually crystallized in the years up to 1956.

It was against the backdrop of growing discontent with U.S. Cold War policy in Japan and Okinawa that the JCLU compiled an investigative report on occupied Okinawa. Transnational grassroots networks played a role in paving the way. Baptist Reverend Otis W. Bell’s article “Play Fair with Okinawans!” in the January 1954 edition of The Christian Century triggered a cascade of events. This article written by a resident of Okinawa gave a vivid account of the military’s coercive confiscation of land from Okinawan farmers. Even though Bell endorsed the American military’s Cold War rationale and its presence in Okinawa, he rejected USCAR’s labeling of the local resistance as a “communist” conspiracy: “One would expect to find a small percentage of the people affected by communist propaganda, but in a country that has been occupied by the U.S. army for eight years one would not expect to find 98 percent of the landowners communists or sympathetic to communism.” He warned: “The Okinawan leaders know better. They know there will be trouble until the land problem is settled…”31

The lawyer and co-founder of the ACLU Roger Baldwin read Bell’s article. In February 1954, Baldwin wrote a letter to the president of the JCLU Unno Shinkichi (海野晋吉) calling for an investigation into the state of U.S.-occupied Okinawa:

Protests by Okinawans are said to be answered by American military authorities with charges of communism. We have no correspondent in Okinawa, but I suppose you do. Can you get the facts which perhaps the Japanese has published, and let us have your judgement? We will then take it up with American authorities. Or is it possible that you might effectively protest to American command in Tokyo. We presume Tokyo is controlled by the Tokyo Far Eastern Command.32

At that time, solidarity activism related to Okinawa was mainly organized by Okinawa-born residents mainly.33 Nevertheless, some Japanese and Okinawan organizations began to gather information on occupied Okinawa and organize solidarity campaigns in Japan.34 In June 1954, Okinawan students in Japan published a collection of anonymous essays, Okinawa Without a Homeland (祖国なき沖縄), on problems facing garrisoned Okinawa, from prostitution to military-related incidents, labor rights, the base economy, and military land seizures. A foreword by the leftist public intellectual Nakano Yoshio praised the young Okinawans’ understandably passionate, writings and urged the Japanese public to treat the problems Okinawans were facing as their own.35

The JCLU contributed to transforming the emergent transnational Okinawa-Japan-U.S. grassroots networks into a political action that would generate changes in Japanese and U.S. consciousness and policies on Okinawa. The JCLU had been fighting legal battles to “expand fundamental human rights” under a new democratic constitutional order since its establishment in 1947. About twenty legal professionals and activists founded the organization, inspired by the prominent American lawyer Baldwin who visited occupied Japan at the invitation of General MacArthur. The General intended to solicit Baldwin’s observation of Japan, a country that appeared, in MacArthur’s eyes, still filled with “feudal” values, especially among farmers and the general public.36 Chief of the Legislation and Justice Division of Legal Section of GHQ Alfred Oppler welcomed the JCLU’s “emphasis upon individual rights” unlike “public procurators…, who stressed the interest of the state in a vigorous enforcement of the criminal law…”37 During the occupation, the New Dealers among the occupation authorities worked with the JCLU to prevent Japan from becoming a police state again.

While Bell had justified his campaign against the land seizure in Cold War terms, the JCLU handling of Baldwin’s inquiry into the American military occupation of Okinawa was influenced by Cold War politics in mid-1950s Japan. In 1954, some members of the JCLU, fearful of being labeled “communist,” opposed JCLU involvement in the “Okinawa problem.” Others began to associate the “Okinawa problem” with the political agenda of decolonizing Asia, by which they meant resisting the Cold War order that perpetuated the logic of the old colonial empires. Among the latter were Ushitomi Toshitaka and Hagino Yoshio (萩野芳夫), who went ahead with an investigation motivated by what they saw as a stark contrast between the political atmosphere of democratized post-occupation Japan and the authoritarian governance in the U.S.-occupied Ryukyuan islands.38 Tokyo University Assistant Professor and chief author of the JCLU report Ushitomi published a report on his visit to the Amami Islands in December 1953, shortly before the islands’ reversion to Japan.39 According to Hagino, who visited Amami with him, their sense of responsibility grew from the realization that “Okinawans [were] treated as slaves, not humans.”40 The team conducted a ten-month investigation, gathering oral testimonies of Okinawan students in Japan as well as both official and unofficial documents from writers and journalists who had connections with Okinawa. One of the collaborators was the renowned Okinawan journalist Ikemiyagi Shūi (池宮城秀意).41

The outcome was a report titled “Human Rights Problems in Okinawa” addressing numerous “human rights violations”: the legal structure of the U.S. occupation regime, the racialized unequal wage difference between Okinawan and Japanese/Filipino base-construction workers, the coercive land seizure, the undemocratic handling of courts-martial involving OPP members,42 and the high rate of military-related incidents such as rape. Even though the report did not squarely criticize U.S. and Japanese authorities, it argued that the Japanese public must acknowledge the violation of fundamental human rights in Okinawa as their problem with attention to Articles 73 and 74, Chapter XI of the UN Charter titled “Declaration regarding Non-Self-Governing Territories.” These articles stipulated the protection of human rights of peoples whose governance was administered by UN member states.43 Japan was not yet a UN member state, but the United States was.

The Asahi Coverage: Subjectivity and Passivity in Post-Occupation Japan

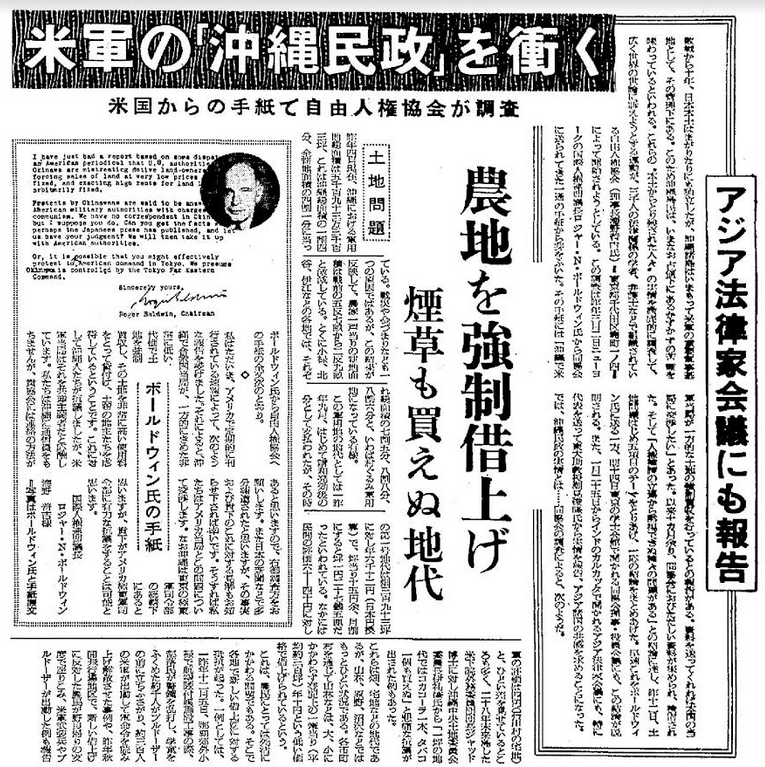

The JCLU report came into the spotlight as a result of the “Asahi coverage.” The Asahi reporter Iwashita Tadao (岩下忠雄) penned a highly favorable front-page article about the JCLU action just as Japanese and U.S. officials were in negotiations about Japan’s participation in the Bandung Conference. Iwashita found the revelations credible due to the prominence of the JCLU—with the participation of lawyers and judges—and that of Baldwin, who had allegedly “stopped GHQ from censoring letters due to its inconsistency with democracy.” Iwashita did not simply rely on the JCLU report but also conducted interviews with Okinawans and collected relevant sources to substantiate the findings.44

The Asahi Shinbun’s front page article on the JCLU report with a headline titled “Hitting home the American military’s ‘civilian governance in Okinawa’” (January 13, 1955) All rights reserved (The Asahi Shinbun authorization number: 22-1227).

On January 13, the Asahi Shinbun ran the first article on the subject, publishing Baldwin’s letter to JCLU President Unno, a summary of the JCLU report, and legal scholars’ comments on the revelations. This front-page article also reported on the JCLU’s plan to address the “Okinawa problem” at the Conference of Asian Lawyers, scheduled to be held in Calcutta, India, later that month. Unno commented that he was embarrassed to have been informed of “things related to fellow Okinawans” from Baldwin, an American. The well-known legal scholar at Tokyo University Yokota Kisaburō (横田喜三郎) told the Asahi Shinbun that even though Japan would not be able to call on the United States to commit to the spirit of the UN Charter regarding Non-Self-Governing Territories and other human rights related regulations due to its non-member-state status, Japanese people could still advocate for the protection of Okinawans’ human rights. Informing American citizens of the problem might help in changing U.S. policy on Okinawa, Yokota stated. The prominent Okinawan journalist and politician Nakayoshi Ryōkō (仲吉良光), based in Tokyo, also supported the JCLU initiative, telling the press that about eighty percent of Okinawans favored reversion. He also insisted that a critical attitude toward military rule did not automatically mean that one was “anti-American.”45

At a quickly called board meeting at Tokyo University on January 14, about twenty JCLU members and some observers from the Ministry of Justice listened to a briefing on the background of the report and the intention behind its publication. Unno suggested that “it would be best to avoid politicizing [the report’s findings] and [instead] treat them as pure human rights issues.” Ushitomi, who would present the report for Asian legal professionals within two weeks, explained the sources he had used to compile it. Okinawan participants, who had spoken anonymously to the Asahi, now added details to the information already provided. Chairperson Morikawa Kinjyu (森川金寿) assured the participants and the press that the JCLU would stay away from partisan politics and instead call on the Foreign Ministry to treat the issues as “pure human rights problems” and strive to raise public awareness.46

Indeed, the JCLU members’ sensitivity toward the “politicization” of the “Okinawa problem” reflected the broader political environment of mid-1950s Japan, where Japanese officials were also exploring how to strike a balance between anti-communism and neutralism. Needless to say, Japan’s political role in institutionalizing the San Francisco System and the “Okinawa problem” as a consequence required a political consciousness that the Japanese population bore responsibility for the islanders’ plight. However, JCLU members were far from unanimous on such a conclusion. For instance, Hosei University professor Nakamura Akira (中村哲) told the Asahi Shinbun that it was important for the Japanese to treat [Okinawa related] issues as “fundamental human rights problems” regardless of the question of national sovereignty and to eventually solve them with the power of national cohesion as “peoples sharing the same blood.”47

U.S. authorities responded strongly to the Asahi’s coverage of the JCLU revelations. On January 14, Deputy Governor of USCAR David A. D. Ogden dismissed the allegation of the military’s low compensation for the lease of native land as communist propaganda and pointed out the lack of an on-site investigation.48 The Asahi Shinbun countered that the JCLU’s “sources were reliable.”49 On January 16, the Far East Command (FECOM) released the following rebuttal to the JCLU:

The nature of the exhaustive ‘investigation’ is not known to this h[ead]q[arters] because the ‘investigators’ did not even visit Okinawa… Stories about Okinawa, based on hearsay, rumour, misinformation and prejudice, are not unique. As recently as Dec 30 and 31, 1954, a series of 2 such art[icle]s, advancing strang[e]ly similar groundless allegations, appeared in Akahata, the organ of the Communist Party in Japan.50

In addition, FECOM argued that the wage differential resulted from the military’s consideration of the skills of Filipino and Japanese workers that Okinawan workers lacked. On the military trials of leftist Okinawans without legal representation, FECOM blamed the accused, who had requested the appointment of Japanese lawyers and allegedly tried to delay the trials. The military authorities in Tokyo argued that political freedom was protected, as seen in free discussions on the land problem in local newspapers.51 The defense officials’ resort to anti-communist rhetoric and claims of a racial hierarchy between “skilled” Japanese workers and “unskilled” Okinawans surely did not defuse the issues. Yet their reference to the political freedom of the Okinawan press—in fact, regulated by USCAR’s license system—was a testament to the shifting political dynamics of the Okinawa-Japan-U.S. relationship. U.S. policymakers were, only now, compelled to explain the existing structure of military rule in terms of democratic principles in “democratized” Japan, finding themselves on the defensive for the first time in a decade. It was a defense that surely highlighted the paucity of democratic rights in occupied Okinawa compared with the constitutional guarantees in post-occupation Japan.

The political impact of the Asahi coverage was immediate. The paper received numerous letters from Japanese and Okinawan readers.52 In the Diet, opposition parties pressured the Hatoyama administration to make greater efforts to improve the welfare of Okinawans living under U.S. administration. In response, Hatoyama stated: “Although naturally, I am obliged to maintain our close cooperation with the United States, I still insist on boldness and honesty where insistence is due since I believe that the Japan-U.S. relationship will improve by doing so. Following the course of action [subservient diplomacy] suggested by the United States is the root cause of anti-American feelings today.”53 The Hatoyama administration officially accepted the invitation to attend the Bandung Conference scheduled to be held in April, with an eye to prove his “independent” diplomacy amidst these new political developments both at home and abroad.54 Further, increasing public demand for Japan’s autonomous sovereign status was manifested in the results of the general election of February 1955, in which Hatoyama’s Democratic Party secured the largest number of seats and the Leftwing Socialist Party dramatically enhanced its position from the loss of seats of Yoshida’s Liberal Party.55

However, to those who had been calling on the Japanese population to respond to the “Okinawa problem” since well before the Asahi coverage, this sudden awakening was a mockery. Indeed, recalled the prominent Okinawan journalist Ikemiyagi Shūi, he himself had written about U.S.-occupied Okinawa, including the land problem, when the Mainichi Shinbun reported on Okinawa, sometimes running front-page articles in the “international section,” but they did not garner nearly the public attention that the Asahi coverage of the JCLU report did in 1955. To be sure, no members of the Communist or Socialist parties, journalists or writers were allowed to travel to Okinawa at that time. Public concern about Okinawa, even among the progressive political parties, was slow to emerge in Japan, according to Ikemiyagi.56

Likewise, Japanese novelist Hino Ashihei (火野葦平) pointed to the racialized political consciousness of the Japanese that had delayed awakening to the “Okinawa problem” in his article titled “Japan lacks self-realization,” published in the Ryukyu Shimpo on February 5. Hino noted that his numerous articles in newspapers and magazines, as well as lectures on the “hardship and perseverance of the Ryukyuan people,” based on his private visit to Okinawa in February 1953 “had no impact.” He recalled that a Diet member learning about his visit, expressed “not the slightest interest.” Instead, “a letter by Mr. Baldwin, an American, threw the Japanese into a state of confusion… The Japanese people are in the habit of being agitated and confused when their own problems are pointed out by outsiders.”57 This pattern of Euro-American voices being deemed more important than domestic ones was indeed a long-standing and profound problem in Japan’s political culture.

The “Okinawa Problem” and the Decolonizing World: Possibilities and Limitations of “Transnational” Activism, 1955

The explosion of the public debate in Japan over the “Okinawa problem” and efforts to spread solidarity activism with Okinawa in Asia caught the U.S. State Department by surprise. The American Embassy staff in Tokyo had been unaware of the JCLU’s investigation before the Asahi coverage. On January 14, Ambassador Allison reported to Secretary of State John Foster Dulles that the Asahi Shinbun was pressuring the Hatoyama administration to “correct mistreatment [of] Okinawans as [a] necessary step in his effort to eliminate anti-Americanism.” Further, he alerted Dulles to the fact that Japanese lawyers would address the military’s human rights violations in Okinawa at the Asian Jurists Meeting in India, which could influence the “Japanese [general] election [to be held on February 27].”58

Inevitably, U.S. civilian officials’ concern over the emergence of the “Okinawa problem” in post-occupation Japan entailed the possible impact of Japanese solidarity activism with Okinawa on Afro-Asian countries, which were in search of regional networks. On January 21, Dulles disseminated a joint State-USIA (U.S. Information Agency) message addressed to Calcutta, New Delhi, Tokyo, and Naha, demanding that officials in each U.S. foreign post collaborate in implementing countermeasures:

Defense today sending message FEC requesting press material supporting U.S. position from Okinawan sources be sent soonest USIS Calcutta and Tokyo for discretionary use. Only very limited quantity such materials expected. Our job to present materials (FEC statement and Okinawan stories) preferably through indigenous channels, supporting U.S. administration and showing exaggeration or falsity JCLU charges if charges presented and publicized. Otherwise do not undertake publicity our side of controversy.59

Within a few days, Deputy Governor of USCAR Ogden conveyed statements to both local and English-language media about coverage of the JCLU report filled with dismissive comments by pro-USCAR Okinawan leaders, the FEC, and the Ryukyus Command (RYCOM).60 These defensive moves suggest the effectiveness of the JCLU report.

The political momentum created by the JCLU intensified U.S. policymakers’ discussion on the structural problems of the occupation of Okinawa. One result was to give the State Department a greater advisory role in administering Okinawa as Dulles had been requesting.61

On January 24, at the request of the Defense Department, a working group which included representatives of the State and Defense Departments, CIA, USIA, Foreign Operations Administration (FOA), and Operation Coordination Board (OCB) discussed how to counter the allegations of the JCLU report. The problem was that “U.S.-Japanese relations, as well as American military prestige, are being adversely affected by current Tokyo press emphasis of Japanese Civil Liberties Union charges alleging mistreatment and maladministration of Okinawans on the part of the Far East Command.” As to the cause of the problem, the memorandum of this meeting and the prepared documents emphasized the influence of “international communism” on the JCLU. However, the representatives recognized that “[a] basis apparently exists for certain legitimate grievances on the part of Okinawans in connection with the U.S. land acquisition program and U.S. employment of indigenous labor.” Thus, the working group agreed to adopt “[a] mild approach” towards diminishing the impact of the allegations after considering whether or not “a major effort should be made to counter the allegations,” such as a higher-level statement than the FEC’s. This “mild approach” implied the discussion of long-term policy questions based on further details on the U.S. administration of Okinawa (beyond the FEC rebuttal).62 It eventually led to the appointment of a U.S. State Department official, John M. Steeves, as Foreign Relations Consultant to USCAR in May 1955; he would play an integral role in attempting to contain Okinawans’ uprising against U.S. military injustices in September.63

Notably, changes in U.S. policy on Okinawa occurred in tandem with a similar change towards the Bandung Conference. On January 25, Dulles informed Japan and other U.S. allies that the United States would actively support their participation, aiming to contain the rise of “Asia for Asians” sentiment through their joint presence. The following day, the Hatoyama administration announced its decision to attend the conference.64

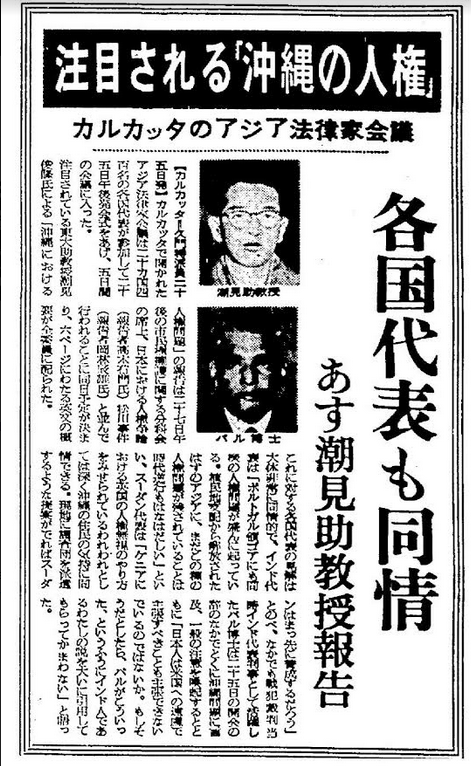

In this charged political climate, twenty-two Japanese delegates, most of whom were legal professionals, eager to exchange views with their Asian counterparts on the future of Asia, travelled to India to attend the Conference of Asian Lawyers from January 25th to 31st.65 There, Ushitomi proposed in front of four hundred lawyers from twenty countries that Asian lawyers travel to Okinawa for an on-site investigation.66 The delegates whom he had spoken to between sessions were supportive, and especially Egyptian delegates were eager to join the international investigation.67 The Asahi Shinbun also reported that the delegates who read Ushitomi’s conference paper were “by and large enormously sympathetic.” An Indian delegate spoke to the press about human rights violations in Goa ruled by the Portuguese and condemned the naked legacies of colonialism in Asia by comparing their cases. A Sudanese delegate, familiar with British human rights violations in Kenya, stated that Sudan would be the first to send delegates to Okinawa for the international investigation. The prominent Indian former judge at the Tokyo War Crimes Trial Radhabinod Pal, who provocatively challenged its colonialist premises, also encouraged Japanese citizens, who “cannot assert things to be asserted against the United States, to widely use his [anti-colonial] claims.”68 The conference adopted a resolution on Okinawa, calling on lawyers across the world to wake up to “the deprivation of numerous civil liberties provided to Japanese citizens, and the American military’s illegal punishments of Okinawan residents, including the uncompensated land seizure.” Ushitomi advocated for Okinawans’ rights in the name of universal values and Japanese civil liberties.69 The anti-colonial movement’s solidarity with Okinawa appeared to be promising.

The Asahi Shinbun’s article on the Conference of Asian Lawyers in Calcutta titled “‘Okinawans’ human rights’ receiving attention; sympathetic delegates from each country; Assistant Professor Ushitomi’s presentation tomorrow” (January 26, 1955, evening edition). The portraits are Dr. Ushitomi (above) and Dr. Pal (below). All rights reserved (The Asahi Shinbun authorization number: 22-1227).

The remaining JCLU board members in Tokyo, however, cautioned against connecting with neutralist actors to solve the “Okinawa problem.” Declassified U.S. documents reveal that what American elites feared most was that the African and Asian lawyers might indeed adopt a resolution to launch an on-site investigation in Okinawa.70 The JCLU members in Tokyo agreed to avoid challenging the U.S. government directly in order to avoid “misunderstandings.” And thus, “the most appropriate measure would be to discuss this matter based on facts, whether the investigation would be authorized or not.” Toward this end, the board members chose the International League for the Rights of Man, an organization Baldwin founded in 1942, to work with.71 In other words, amidst the Conference of Asian Lawyers JCLU took a distinctive approach toward the international mobilization of activism on Okinawa.

The way in which JCLU grappled with strategizing the ideological basis of solidarity activism with Okinawa reflected the broader political landscape of mid-1950s Japan when legal professionals were only beginning to understand their place in the Okinawa-Japan-U.S. relationship. To illustrate: the prominent legal journal Hōritsujihō (法律時報) held a round-table discussion on occupied Okinawa in March 1955 with two JCLU board members, Unno and Morikawa Kinju, and two leading legal scholars, Yokota and Nakamura, as participants. For the most part, Yokota explicated the structural underpinnings of the “Okinawa problem” from a legal perspective, and the JCLU members and Nakamura responded by raising questions. Unno stated that the FEC’s labeling of those involved in compiling the report as communists, whether Okinawans or Japanese, was regrettable and expressed his hope that Baldwin would use his authority to change American public opinion on this matter.72 Overall, though, the participants endorsed Unno’s proposal and concluded that due to Japan’s limited legal authority of “residual sovereignty” over the Ryukyu Islands, solidarity activism ought to be launched only within this framework, that is, under the condition that it would not be treated as interference with the United States’ internal policymaking.73 In other words, Japanese legal scholars hardly reflected on Japan’s own responsibility as public intellectuals for having adopted the Peace Treaty without consultation with, still less consent by, Okinawans to a document that secured Japan’s independence (albeit with the continuing presence of U.S. bases and military forces) while perpetuating U.S. rule in Okinawa.

The cover of the March 1955 edition of Hōritsujihō with the title of the roundtable discussion “Legal Problems Regarding Okinawa.”

Despite some JCLU members’ expectations and hope to connect with U.S. civil society to solve the “Okinawa problem,” there was little American government or public interest in the issues.74 Moreover, Baldwin took a step back, given the controversies over Okinawa in Japan following the Asahi report. The Army Department even ventured that Baldwin must have been “embarrassed by the uproar” to learn about the Asahi coverage during his stay in Egypt.75 In fact, Baldwin had contacted the U.S. State and Defense Departments about Bell’s allegation in July 1954. But after a brief communication, the Army Department thought Baldwin satisfied with Washington’s rebuttal and considered the matter closed.76

In the aftermath of the Asahi coverage, Baldwin downplayed the JCLU’s spontaneous activism in his correspondence with defense officials. In his letter to Major General William F. Marquat dated March 5, 1955, Baldwin wrote: “My dear General Marquat… I want you to know—and General Hull too—that we did not inspire the inquiry made by the Japanese Civil Liberties Union, which was widely publicized in the press in January. I would not have solicited aid from a foreign organization concerning any matter under the jurisdiction of our government. I would have gone directly to the proper official.”77 Baldwin’s conciliatory rhetoric was indicative not only of the prevailing power relations between them but also his commitment to U.S. Cold War policy in Asia. He believed that the protection of Okinawans’ basic rights—implying the political and civil liberties guaranteed by the U.S. constitution rather than the international protection of individual rights—and the military occupation were compatible.

The “transnational” Japanese solidarity activism with Okinawa had its limits. Ushitomi’s activism garnered support from the legal professionals representing the decolonizing and newly independent states at the Conference of Asian Lawyers. Yet JCLU’s “international” activism on behalf of Okinawa adopted by the board members in 1955 was premised not on collaborating with Third World actors but on alignment with the U.S.-led Cold War order. Within JCLU, not to mention Japanese society as a whole, there was little understanding of Japanese citizens’ responsibility for securing the rights of Okinawans following Japan’s recovery of sovereignty in 1952, which had been achieved at the cost of the continued U.S. occupation of Okinawa.

Despite the JCLU’s politically ambivalent engagement with the “Okinawa problem” in the mid-1950s, its impact on occupied Okinawa was far-reaching. The Okinawan local press provided extensive coverage of the debate over the “Okinawa problem.” In the meantime, the islanders became increasingly aware of the emergent solidarity activism outside Okinawa at Bandung and elsewhere and the power of human rights advocacy.78 Although Okinawan reactions to the JCLU report were divided, some welcoming, some dismissive, the politics it entailed invoked frequent uses of the term “human rights” in local newspapers. And reports on the Conference of Asian Lawyers and the Bandung Conference gradually raised the islanders’ awareness that Okinawa was no longer a “forgotten island.”

In January, 1955 the Okinawa Times reprinted Japanese legal scholar Iriye Keishirō (入江啓四郎)’s article entitled “The Promise of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights—Also Declared in the Provisions of the Government of the Ryukyu Islands,” initially published by Sunday Mainichi on January 20, 1955 in Japan.79 In April, Okinawan intellectual Kamiyama Seiryō (神山政良), based in Japan, met with Indian Premier Jawaharlal Nehru’s daughter and later Prime Minister herself, Indira Gandhi, who was familiar with the Okinawans’ plight. Nehru had opposed the U.S. occupation of the Ryukyu Islands at the time of the San Francisco Conference, and indeed, he became a chief player in building Third World unity. Nehru’s message that Okinawans “must not lose courage” reached Okinawa.80 In September, the Yumiko-chan GI rape Incident triggered the islanders’ collective employment of the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights and cries for the occupied people’s right to life, equality before the law, and proper compensation for all military-related incidents. In October, “All Okinawan Residents’ Rally for the Protection of Human Rights (全沖縄人権擁護住民大会)” was held in Naha, mobilizing about five thousand residents and nineteen grassroots organizations. Similar demonstrations followed in other areas adjacent to American military bases on the islands. By employing human rights advocacy in forming a suprapartisan front, Okinawans attained the right to attend courts-martial and receive official compensation for criminal cases committed by U.S. military personnel.81

Even though the locals’ exercise of basic rights, including such minimum protection of the above-mentioned rights continued to be subject to USCAR’s whim and strategic calculation, the political impact of the 1955 JCLU report on “base Okinawa” was substantial in that the 1955 uprising taught the locals the transformative power of a popular struggle carried out in a universalist language declared by the United Nations as a marker of post-1945 civilization. In this sense, despite Japanese civil society’s short-lived and uneven attention to occupied Okinawa in the rest of the 1950s, the Japanese legal professionals’ nascent—albeit divided—engagement with Okinawa marked a critical moment in the triangular Okinawa-Japan-U.S. relationship. It was in the mid-1950s—a time when labor unions, progressive political parties, and diverse grassroots organizations dedicated to peace, education, and women’s rights were increasingly reinforcing solidarity networks for “pro-constitution” and peace movements in Japan82—that U.S. policymakers, including Dulles, were compelled to be alert to the link between the emergence of anti-hegemonic neutralism in Asia and the prospect of the consolidation of collective challenges—whether nationalist or internationalist in their outlook—to the U.S. military presence in Okinawa and Japan.

Conclusion

This article has shown the Japanese legal professionals’ engagement with the “Okinawa problem” in the latter half of the 1950s played a role in the rise of Okinawans’ rights activism.

In the aftermath of the Asahi coverage, the Japan Federation of Bar Associations (JFBA) established a special committee to study the “Okinawa problem.”83 The JFBA and JCLU members, closely following the political developments of Okinawa, protested USCAR’s attempt to revise the Penal Code in 1959, which would have prohibited Okinawans from engaging in anti-occupation activities with “foreigners,” including Japanese; it was clearly aimed at preventing the surge of a vibrant reversion movement, whether nationalist or internationalist. The lawyers’ protest aided Okinawans’ resistance and, the measure failed. Further, the 1961 JCLU report on Okinawa—based on an on-site investigation this time—served to underpin the GRI Legislature’s unanimous declaration of 1962 that condemned the U.S. violation of “sovereignty equality” for its deprivation of the “Japanese territory” of Okinawa. It invoked the United Nations’ “Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples,” adopted on December 14, 1960.84 When we retrospectively make these connections, the year 1955 is significant for historical understanding of the Okinawa-Japan relationship, the development of the Okinawan reversion movement that expanded dramatically in the 1960s, and the trajectory of anti-colonial movements in Japan and Okinawa.

Nevertheless, the limits of mid-1950s Japanese solidarity activism must not be dismissed. It is tempting to imagine what would have happened if the JCLU members had pursued third-worldist—or internationalist—approaches critical of the U.S. Cold War rationale for its hegemonic military presence. The proposed Asian lawyers’ international on-site investigation in Okinawa never materialized. Yet, John Foster Dulles feared this most. Certainly, the strength of Unno’s approach rather than Ushitomi’s within JCLU speaks to the broader political landscape of mid-1950s Japan, where U.S. policymakers’ anti-communism effectively suppressed the neutralist elements of Japanese opposition to the occupation of Okinawa. In this climate, most Japanese citizens, as well as politicians and legal professionals alike, did not critically engage with their own responsibility for the “Okinawa problem,” which necessitated a historical reflection on and political consciousness of Japan’s colonial relationship with the Ryukyus and the persistent hierarchy that subsequently defined their relationship following reversion.

The marginalized status of garrisoned Okinawa—intensified by the Eisenhower administration’s realignment of U.S. armed forces in Japan and the transfer of Marines to Okinawa in the latter half of the 1950s—was also reflected in the 1960 Anpo Movement, Japanese citizens’ mass protests against the renewal of the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty (安保闘争). At this epochal moment in Japanese history, the protesters raised “peace and democracy (popular sovereignty)” as their collective demand in response to the Kishi administration’s authoritarian handling of the protests and the further militarization of the Japan-U.S. security relationship.85 However, the question of spatial exception to democracy in Okinawa did not become a major issue in the nation-wide debate over the renewal of the security treaty, as scholars of Okinawa, such as Arasaki, have long insisted.

Finally, this paper has shown the effects of Baldwin’s initiative on grassroots activism in the Okinawa-Japan-U.S. relationship. His lobbying activities expanded from 1955 onward, pressuring U.S. policymakers to modify certain occupation policies. Further, Baldwin’s visit to Okinawa in 1959 inspired locals to found their own Okinawa Human Rights Association (沖縄人権協会) in 1961. Nevertheless, Baldwin’s belief in the Cold War rationale and capitalist modernity emphasized by the occupation, and his embrace of the U.S. military presence in Okinawa must also be noted. In addition, it is crucial to recall that while Baldwin’s inquiry into Okinawa with JCLU in 1954 prompted the investigation, the 1955 Japanese awakening itself was triggered by the JCLU initiative. As Hino and Ikemiyagi pointed to the Japanese sense of racial inferiority to Americans in analyzing Japanese civil society’s much-delayed and sudden awakening to the “Okinawa problem,” this paper has called attention to the way in which the Asahi Shinbun and JCLU relied on Baldwin as an American with connections to General MacArthur to challenge the U.S. government. Similarly, occupied Okinawans widely used his authority to legitimize their activism, a phenomenon that the author’s dissertation discusses in greater detail.86 In short, in order to fully grasp the dynamism of transnational activism, each historical actor’s level of subjectivity requires detailed attention. After all, the 1950s platform of solidarity activism did not break from the premise of the hierarchy between the United States, Japan, and Okinawa.

The Okinawan reversion movement evolved in constant negotiation with the trajectory of Japanese solidarity activism on Okinawa. In the early 1950s, the islanders’ movement for immediate reversion faded soon after Japan’s recovery of sovereignty. Not until the mid-1950s did many Okinawans recognize Japanese civil society’s and Third-World activists’ attention to the plight of the “forgotten” islands. However, given Japanese civil society’s limited attention to the “Okinawa problem,” which became apparent to Okinawan activists in the late 1950s, and during the 1960 Anpo in particular, the efforts of Okinawan activists to mobilize a popular reversion movement became a pressing political agenda in the early 1960s.87 The peak of the so-called “Okinawa struggle (沖縄闘争)” carried out by Japanese citizens came in the latter half of the 1960s, a change made possible by the gradual relaxation of travel bans on Japanese entry into Okinawa as a result of their joint struggle. Together transcending the usual racial, national, and class divides, Japanese activists as well as American citizens and soldiers—far greater in numbers than in the 1950s—joined solidarity activism on Okinawa against the backdrop of the Vietnam War.88 Although the Nixon administration’s major impetus for reversion came from the rise of anti-base sentiment and movements in the occupied islands, a dramatic political development symbolized by the prominent teacher activist and anti-base candidate Yara Chōbyō’s victory in the first democratic GRI Chief Executive election in 1968, the emergence of Japanese and Okinawan joint struggles against the permanet American military presence also became a pressing policy concern for U.S. policymakers especially in the late 1960s.89 With the immense American military facilities authorized to remain in Okinawa, “reversion” materialized on May 15, 1972.

In conclusion, it seems fair to say that the fraught legacies of mid-1950s Japanese solidarity activism speak to the historical problem of Japanese engagement with the “Okinawa problem” marking the fiftieth anniversary of the reversion of Okinawa to Japan. The logic and limits of the mid-1950s “transnational” solidarity activism shed light on the historical trajectory of a marginalized Ryukyus/Okinawa.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the reviewers of this article for their insightful and constructive comments as well as participants of the 2021 Association for Asian Studies Annual Conference Panel “Pacifism, Human Rights, Popular Movement, and ‘History Activism’: The ‘Postwar’ as a Transnational Space” where an earlier version of this paper was presented: Franziska Seraphim, Laura Hein, Igarashi Yoshikuni, Keyao Pan, and Lee Seok-Won. All remaining errors are my own.

Notes

Nakajima Shingo, “Hatoyama Ichirō: ‘Yoshida no subete hantai’ o motomete,” in Sengo nihon no shushō no gaikō shisō, ed. Masuda Hiroshi (Kyoto: Minerva shobō, 2016), 79-108; Shinoda Tomohito, Seiken kōtai to sengo nihon gaikō (Tokyo: Shikura shobō, 2018), 13-23

Watanabe Akio, Sengo nihon no seiji to gaikō: Okinawa o meguru seiji katē (Tokyo: Fukumura shuppan, 1970), 44-45.

Oguma Eiji, “Nihonjin” no kyōkai: Okinawa, Ainu, Taiwan, Chōsenshihai kara fukki undo made (Tokyo: Shinyōsha, 1998), 514-515. See also Koseki Shōichi, Toyoshita Narahiko, Okinawa: Kenpō naki sengo (Tokyo: Misuzu shobō, 2018), 16-20, 110-115.

Arasaki Moriteru, “Sengo Okinawa shinbun hōdō hensenshi,” Shinbun kenkyū no. 215 (June 1969): 23-24.

Sakurazawa Makoto, “Sengo shoki ni okeru hondo gawa no Okinawa kan nitsuite: Sōgō zasshi, fujin zasshi, Keizai zasshi o jirei to shite,” Rekishi kenkyū no. 54 (March 2017): 33-56.

Oguma Eiji, “Postwar Japanese Intellectuals’ Changing Perspectives on ‘Asia’ and Modernity,” The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, Volume 5, Issue. 2, February 2, 2007.

For my analysis of the Yumiko-chan Incident, see Fumi Inoue, “Chapter 3: ‘Extraterritoriality’ in Occupied Okinawa” in “The Politics of Extraterritoriality in Post-Occupation Japan and U.S.-Occupied Okinawa, 1952-1972,” Ph.D. dissertation (Boston College, 2021), 172-242. See also my forthcoming article: Fumi Inoue, “Rethinking the Power of the Voiceless: The Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the and the Birth of Popular Human Rights Activism in Occupied Okinawa,” in The Voiced and Voiceless in Asia, ed. Halina Zawiszová, Martin Lavička (Olomouc: Palacký University Olomouc, 2022). See also Richard A. Serrano and Jon Mitchell, “Okinawa: Race, Military Justice and the Yumiko-chan Incident,” The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, Volume 19, Issue 12, No. 2, November 15, 2021.

Inoue, “Chapter 3: ‘Extraterritoriality’ in Occupied Okinawa,” 172-242; Inoue, “Rethinking the Power of the Voiceless: The Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the Birth of Popular Human Rights Activism in Occupied Okinawa.”

Kōno Yasuko, Okinawa henkan o meguru seiji to gaikō: Nichibei kankeishi no bunmyaku (Tokyo: Tokyo daigaku shuppan, 1994), 122-127; John Swenson-Wright, Unequal Allies? United States Security and Alliance Policy Toward Japan, 1945 – 1960 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2005), 121-133; Watanabe, Sengo nihon no seiji to gaikō, 43-56.

Samuel Moyn, The Last Utopia: Human Rights in History (Cambridge, Massachusetts, and London, England: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2010).

Ono Yuriko, “Okinawa gunyōchi mondai’ ni taisuru hondo gawa no hankyō no kōsatsu: Nihon shakai to ‘Okinawa mondai’ no deai, deai sokonai,” Okinawa bunka kenkyū no. 36 (March 2019): 317-358; Ono Yuriko, “Okinawa henkan kokumin undo kyōgikai ni miru 1950 nendai nakaba no Okinawa henkan undo,” Jinmin no rekishigaku no. 202 (December 2014): 26-36.

Telegram 1556 from W. J. Sebald, Chief, Diplomatic Section to Secretary of State, February 12, 1951, RG 84, Records of the Foreign Service Posts of the Department of State, Japan, Office of U.S. Political Advisor, Classified General Records, 1945-1952, Box 60, Folder: 320.1 Peace Treaty, January-March, 1951, National Archives II, College Park, Maryland [hereafter cited as NARA].

For a succinct overview of the San Francisco System, see John W. Dower, “The San Francisco System: Past, Present, Future in U.S.-Japan-China Relations サンフランシスコ体制 米日中関係の過去、現在、そして未来,” The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus Volume 12, Issue 8, No. 2, February 24, 2014.

Treaty of Peace with Japan, signed at the city of San Francisco, the United States of America on September 8, 1951, ratified on November 18, 1951, and entered into force on April, 28, 1952. Treaty of Peace with Japan, signed at the city of San Francisco, the United States of America on September 8, 1951, ratified on November 18, 1951, and entered into force on April, 28, 1952.

Kōno, Okinawa henkan o meguru seiji to gaikō, 29-62; Koseki, Toyoshita, Okinawa: Kenpō naki sengo, 42-60.

Michael J. Hogan, A Cross of Iron: Harry S. Truman and the National Security State 1945-1954 (New York and Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 17

The United Nations General Assembly, The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted on 10 December, 1948.

Mary Ann. Glendon, A World Made New: Eleanor Roosevelt and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (New York: Random House, 2001), 21–34, 205; Moyn, Last Utopia, 76, 125; Oliver Barsalou, “The Cold War and the Rise of An American Conception of Human Rights, 1945-1948,” in Revisiting the Origins of Human Rights, edited by Pamela Slotte and Mila Halme-Toumisaari (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015), 362–380; Brad Simpson, “Bringing the Non–State Back In: Human Rights and Terrorism since 1945,” in America in the World: The Historiography of American Foreign Relations since 1941, edited by Frank Costigliola and Michael Hogan (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014), 2014, 261–263.

Inoue, “Chapter 2 The Birth of the American Military Legal Regime of Exception in Post-Occupation, Japan,” in “The Politics of Extraterritoriality in Post-Occupation Japan and U.S.-Occupied Okinawa, 1952-1972,” 81-171.

For in-depth analyses of the Sunagawa struggle, see: Jennifer M. Miller, Cold War Democracy: The United States and Japan (Harvard University Press, 2019), Dustin Wright, “From Tokyo to Wounded Knee: Two Afterlives of the Sunagawa Struggle,” The Sixties 10, no. 2 (July 2017): 133–49.

The first wave of large-scale Japanese engagement with the “Okinawa problem” came in 1956 when the U.S. Congress approved the military’s land policy and the so-called “Price Report” ignited Okinawans’ island-wide protest movement. For instance, see: Watanabe, Sengo nihon no seiji to gaikō, 191-219.

“The Four Principles” refer to opposition to the military’s one-time payment, proper compensation for seizure, compensation for damages. See Sakurazawa, Okinawa gendaishi, 50-51.

Roger Baldwin, Chairman, to Shinkichi Unno, Japanese Civil Liberties Union, February 23, 1954, American Civil Liberties Union Records MC #001, 1917, Subject Files, International Civil Liberties, 1946-1977, Box 1173, Folder: 32 Japan Correspondence, 1954-1956, Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library, Princeton University.

Sakurazawa, “Sengo shoki ni okeru hondo gawa no Okinawa kan nitsuite, 33-56; Watanabe, Sengo nihon no seiji to gaikō, 220-244.

Nakano Yoshio, “Hifun no shima Okinawa no kiroku,” Sokoku naki Okinawa (Tokyo: Jitsugetsu sha, 1954), pages not allocated.

Unno Shinkichi, Morikawa Kinjyu, Nijūnen no ayumi: Jiyūjinken kyōkai (Tokyo: Jiyūjinken kyōkai, 1967), 10-13.

Alfred C. Oppler, “The Reform of Japan’s Legal and Judicial System Under Allied Occupation,” Washington Law Review Vol. 24, No. 3 (August 1949): 1, 8.

Ikemiyagushiku (Ikemiyagi) Shūi, Okinawa Jānalisto no kiroku—Okinawa no America (Simul Shuppan: Tokyo, 1971), 176-179.

The latest work on this case (Jinmintō jiken), see: Morikawa Yasutaka, Okinawa Jinmintō jiken—Beikoku minseifu gunji hōtei ni tatsu Senaga Kamejirō (Tokyo: Impact shuppan, 2021).

United Nations, United Nations Charter, Chapter XI: Declaration Regarding Non-Self-Governing Territories, signed on 26 June 1945, and came into force on 24 October 1945.

Iwashita Tadao, “Sono toki watashi wa,” in Okinawa no shōgen: Gekidō no 25 nen shi–ge, ed. Okinawa Times sha (Naha: Okinawa Times sha, 1973), 156-159.

Message from Department of the Army Staff Communications Office, CINCFE Tokyo, Japan (J5) to DEPTAR Washington DC for CAMG, CINFO DEPTAR Washington DC, January 16, 1955, RG 319 Records of the Army Staff, Records of the Office of the Chief of Civil Affairs, Security Classified Correspondence of the Public Affairs Division, 1950-1964, Box 1, File: Allegations of Japanese Civil Liberties Union Against U.S. Administration of Okinawa, Volume 1, July 1954-May 1955, NARA.

Message from Department of the Army Staff Communications Office, CINCFE Tokyo, Japan (J5) to DEPTAR Washington DC for CAMG, CINFO DEPTAR Washington DC, January 16, 1955, NARA.

Ishikawa Masumi, Yamaguchi Jirō, Sengo seijishi, Third edition (Tokyo: Iwanami shoten, 2015), 70-71.

Telegram 1695 from Allison (Tokyo Embassy) to Secretary of State, January 14, 1955, RG 319 Records of the Army Staff, Records of the Office of the Chief of Civil Affairs, Security Classified Correspondence of the Public Affairs Division, 1950-1964, Box 1, Folder: Allegations of Japanese Civil Liberties Union Against U.S. Administration of Okinawa, Volume 1, July 1954-May 1955, NARA.

Telegram 1462 from Dulles to Calcutta, New Delhi, Tokyo, Naha, “Joint State-USIA message,” January 21, 1955, RG 84 Records of the Foreign Service Posts of the Department of State, Japan, Tokyo Embassy, Classified General Records, 1952-1963, Code Number: 084-02828A-00024-009-093, Okinawa Prefectural Archives [hereafter cited as OPA]; Message from SECY OF STATE WASH DC SGD DULLES to USCONGEN CALCUTTA INDIA, January 21, 1955, RG 319 Records of the Army Staff, Records of the Office of the Chief of Civil Affairs, Security Classified Correspondence of the Public Affairs Division, 1950-1964, Box 1, Folder: Allegations of Japanese Civil Liberties Union Against U.S. Administration of Okinawa, Volume 1, July 1954-May 1955, NARA.

Message from DEPGOVUSCAR (Deputy Governor of the United States Civil Administration of the Ryukyu Islnads) to USCONGEN, CALCUTTA, INDIA, FOR USIS, January 25, 1955, RG 319 Records of the Army Staff, Records of the Office of the Chief of Civil Affairs, Security Classified Correspondence of the Public Affairs Division, 1950-1964, Box 1, Folder: Allegations of Japanese Civil Liberties Union Against U.S. Administration of Okinawa, Volume 1, July 1954-May 1955, NARA.

Operations Coordinating Board, “Memorandum of Meeting: Working Group on NSC 125/2 and NSC 125/6,” January 24, 1955, RG 84, Records of the Foreign Service Posts of the Department of State, Japan, Tokyo Embassy, Classified General Records, 1952-1963, Folder 323: Ryukyus, Code Number: 084-02828A-00024-009-080, OPA.

Inoue, “Chapter 3: ‘Extraterritoriality in Occupied Okinawa,’” 172-242; Inoue, “Rethinking the Power of the Voiceless: The Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the Birth of Popular Human Rights Activism in Occupied Okinawa.”

Ushitomi Toshitaka, “Indo to chūgoku no tabi,” Hōritsujihō 27, no.299 (March 1955): 57; Asahi Shinbun, evening edition, January 26, 1955.

Telegram 1614 to the U.S. Embassy in Tokyo, February 15, 1955, RG 84, Records of the Foreign Service Posts of the Department of State, Japan, Tokyo Embassy, Classified General Records, 1952-1963, Folder 323: Ryukyus, Code Number: 084-02828A-00024-009-065, OPA; Telegram 17 from Realms, February 16, 1955, RG 84, Records of the Foreign Service Posts of the Department of State, Japan, Tokyo Embassy, Classified General Records, 1952-1963, Folder 323: Ryukyus, Code Number: 084-02828A-00024-009-064, OPA.

DA 978464 from CAMG for J-5 to CINCFE TOKYO JAPAN, February 2, 19, 1955, RG 319 Records of the Army Staff, Records of the Office of the Chief of Civil Affairs, Security Classified Correspondence of the Public Affairs Division, 1950-1964, Box 1, Folder: Allegations of Japanese Civil Liberties Union Against U.S. Administration of Okinawa, Volume 1, July 1954-May 1955, NARA.

“Allegations of Japan Civil Liberties Union Against U.S. Administration of Okinawa, Chorological Record,” undated, RG 319 Records of the Army Staff, Records of the Office of the Chief of Civil Affairs, Security Classified Correspondence of the Public Affairs Division, 1950-1964, Box 1, Folder: Allegations of Japanese Civil Liberties Union Against U.S. Administration of Okinawa, Volume 1, July 1954-May 1955, NARA.

“Allegations of Japan Civil Liberties Union Against U.S. Administration of Okinawa, Chorological Record,” undated, NARA.

Letter from Ernest Angell (Chairman, Board of Directors) and Roger Nash Baldwin, International Civil Liberties Committee, American Civil Liberties Union, to Major General William F. Marquat, March 24, 1955, RG 319 Records of the Army Staff, Records of the Office of the Chief of Civil Affairs, Security Classified Correspondence of the Public Affairs Division, 1950-1964, Box 1, Folder: Allegations of Japanese Civil Liberties Union Against U.S. Administration of Okinawa, Volume 1, July 1954-May 1955, NARA.

Inoue, “Chapter 3: ‘Extraterritoriality’ in Occupied Okinawa,” 172-242; Inoue, “Rethinking the Power of the Voiceless: The Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the Birth of Popular Human Rights Activism in Occupied Okinawa.”

Inoue, “Chapter 3: ‘Extraterritoriality’ in Occupied Okinawa,” 172-242; Inoue, “Rethinking the Power of the Voiceless: The Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the Birth of Popular Human Rights Activism in Occupied Okinawa.”

Watanabe Osamu, “Anpo tōsō no sengo hoshu seiji eno kokuin,” Rekishi hyōron no. 723 (July 2010): 4-23. For recent English scholarship on the Anpo, see: Nick Kapur, Japan at the Crossroads: Conflict and Compromise after Anpo (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2018).

For a more detailed analysis of Okinawans’ reactions to Baldwin’s activism and visit to Okinawa, see Inoue, “Chapter 5 From the Anpo to the Koza Rebellion: An Overture to Okinawa’s Entry into the Japan-U.S. Status of Forces Agreement,” in “The Politics of Extraterritoriality in Post-Occupation Japan and U.S.-Occupied Okinawa, 1952-1972,” Ph.D. dissertation (Boston College, 2021), 300-355.

For empirical analyses of and further discussions on 1960s-1970s transnational activism forged by Okinawans, Japanese, and Americans in Okinawa, see Ōno Mitsuaki, Okinawa tōsō no jidai 1960/70: Bundan o norikoeru sisō to jissen (Kyoto: Jinbun shoin, 2014); Yuichiro Onishi, Transpacific Antiracism: Afro-Asian Solidarity in 20th-Century Black America, Japan, and Okinawa (New York and London: New York University Press, 2008); Wesley Iwao Ueunten, “Rising Up from a Sea of Discontent: The 1970 Koza Uprising in U.S.-Occupied Okinawa,” in Militarized Currents: Toward a Decolonized Future in Asia and the Pacific, ed. Setsu Shigematsu, Keith L. Camacho (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010), 91-124.

See Inoue, “Chapter 5 From the Anpo to the Koza Rebellion: An Overture to Okinawa’s Entry into the Japan-U.S. Status of Forces Agreement,” in “The Politics of Extraterritoriality in Post-Occupation Japan and U.S.-Occupied Okinawa, 1952-1972,” Ph.D. dissertation (Boston College, 2021), 300-355.