Abstract: This paper examines a protest tour in Okinawa in which participants travelled from different prefectures in Japan to protest against construction of a new military base at Henoko. Drawing on participant observation, surveys, and interviews with group members and a peace-tour guide, it examines how participants experienced Okinawa as a destination of political activismm, and assesses their experience. The tour contributed to developing a sense of solidarity among the participants in support of demilitarization in Okinawa. Protest tourism provided a space for education about militarism on the ground. However, drawing from the fields of critical tourism studies and indigenous studies, the paper also draws attention to the challenges of framing a protest tour as a strategy for demilitarization. I develop the notion of “souvenirs of solidarity” to reflect on broader issues concerning US bases in Okinawa, Japan and the Pacific and the possibilities for anti-base activism.

Keywords: Activism, bases, Japan, militarism, Okinawa, protest tourism, solidarity

Introduction

On May 16, 2015, I joined a three-day tour in support of the protest movement against military bases in Okinawa. Over 40 participants, travelling from other parts of Japan, arrived at Naha Airport to join in the protest and support the present struggle against the construction of a US military base at Henoko, Nago City. The participants opposed the Japanese government’s plan to relocate Marine Corps Air Station Futenma, currently located in a densely population urban area, to the rural and undeveloped coast of Henoko in northern Okinawa Island.

On our first night, at a dinner with Okinawan dishes and musical performance, the tour participants passionately sang together the following song:

かたき土を破りて 民族のいかりにもゆる島 沖縄よ

我らと我らの祖先が 血と汗をもって 守りそだてた沖縄よ

我らは叫ぶ 沖縄よ 我らのものだ 沖縄は

沖縄を返せ 沖縄を返せ

After breaking the hard soil, Okinawa, the islands are ablaze with a nation’s anger.

Okinawa, the place we and our ancestors protected and raised with our blood and sweat.

We shout, Okinawa! Okinawa is ours!

Return Okinawa! Give Okinawa back to us!

As an Okinawan researching the movement and the tour, I could not confess to the group that I was unfamiliar with this song, which conveys the bonding of Japanese peace activists with the Okinawan movement to prevent the new base’s construction on islands far from their homes. Later, I learned that a labor union in Fukuoka Prefecture had penned “Okinawa wo Kaese” (Return Okinawa) in 1956. It was a popular anthem during the Okinawa reversion movementm which succeeded in reincorporating the islands as a Japanese prefecture in 1972 – leaving, however, all US bases intact. The tour members’ familiarity with the song symbolizes their connection to the reversion movement and reenactment of solidarity with Okinawa, a common practice among leftist Japanese social movements of “nostalgic commemorations” (Steinhoff, 2013, p. 127). What the notion of “nostalgia” reveals is that the participants involved in the Okinawa reversion movement in the 1960s see the ongoing base issues there as the extension of past political activism.

At least 17 participants had learned of the tour through Akahata, the Japanese Communist Party newspaper, suggesting the political inclinations of at least some tour members. The Japanese Communist Party has long opposed militarism and aligns with the anti-military movement in Okinawa. 74 percent of the tour members who responded to my survey had participated in protest events prior to this tour, including anti-nuclear power plant rallies, labor union demonstrations, anti-war protests, and the Okinawa reversion movement. While the song celebrates the longing for reversion, however, it ignores the critical issue that drew many Okinawans to reversion: the return of their land expropriated for constructing US bases. After the reversion, the US-Japan alliance continued to map Okinawa as the epi-center of their security politics, enabling over 70% of US military forces to remain on the islands. The political reincorporation of Okinawa to Japan in 1972 did not result in the return of the land and while the song commemorates the heated movement for reversion, and half a century later, questions of land and demilitarization remain unsolved.

In this paper, I examine protest tourism as a unique form of solidarity between anti-base Japanese activists and anti-military protest in Okinawa. Growing up in Okinawa, my family took me multiple times to large outdoor rallies called People’s Rallies (kenmin taikai). For example, kenmin taikai in 2007 took place simultaneously on multiple islands in the Okinawan archipelago – Okinawa, Miyako, Ishigaki Island – mobilizing over 110,000 people. The rallies protested the Japanese government’s decision to delete information in history textbooks on the role of the Japanese military in enforcing group suicides among Okinawans in the final stages of World War 2. Numerous rallies were held in response to incidents during Battle of Okinawa, as well as US military base issues.

When I first learned about the 2015 tour, I recalled how my family had prepared ice-cold tea, hats, paper fans, towels, and snacks to endure the scorching sun and packed venues in previous rallies. On cue, we would raise placards high, but I remember feeling self-conscious about yelling so loudly. Without association with specific political parties or regular involvement with activism, my family saw our attendance as an opportunity to express our deep desire for demilitarization and to join others in our community. My mother often told me our participation was “for your children and grandchildren.” Lummis (2019b) describes in detail the experiences of and interactions with those who attended sit-ins at Henoko, highlighting strong popular commitment to carry on the protest and to prevent the completion of a new base.

Unlike those in Lummis’ study who repeatedly visited the protest site on their own or organized shuttles within Okinawa, the focus of this paper is on those who visit Okinawa in a packaged tour with itinerary consisting of sites related to military bases and the history of protest on the islands. As Lummis points out, the framing of the anti-base movement by Okinawans has shifted “from a left-right issue to a more complex set of issues that includes Okinawan ethnic pride” (p.5), In the following sections I show how protest as a form of tourism maye elide such complexities as Okinawan self-determination in the process of defining demilitarization.

I was curious to learn why people would fly across the country for this event and the nature of their experience. I had two main research questions. First, how does the protest tour address the ongoing issues of militarism in Okinawa, particularly the controversies over the building of a base by reclaiming Ōura Bay? And second, how do the tour participants interpret their experiences? In answering these questions, I explore how the protest tour intersects with the local anti-base movement. At the conclusion of my research, I arrived at my most important research question: how might demilitarization activism better contribute to the realization of the cultural and political aspirations of people on the ground in Okinawa? My hope is that asking this question I may help reorienting the study of demilitarization towards the people on the ground who are directly impacted.

Drawing on participant observation, surveys, and formal and informal interviews with the tour members and a peace-tour guide from the Okinawa Peace Network, I examine the ways in which participants experience and interpret Okinawa as a destination of political activism. I draw attention to the tour participants’ authentic experience of militarism and protest in Okinawa and reflect on its wider implications for war and peace in Japan and the Pacific.

Kichi to kankō no shima: the islands of military bases and tourism

The political history of the islands of Okinawa has long been bound up with China and Japan. The Ryukyu Kingdom, whose trade networks extended throughout the Pacific, maintained a tributary system with China’s Ming dynasty from the 14th century. In 1609, the Satsuma clan invaded and subordinated the Ryukyus, and 270 years later imperial Japan annexed the Ryukyu Kingdom as Okinawa Prefecture. Japanese imperialism led to stigmatization of Ryukyuan cultural practices and Okinawan languages, with an assimilation process promoted by Japan and Ryukyu elites and administration in the name of modernization (Meyer, 2020). Schools, teaching exclusively in Japanese, punished those who spoke in uchināguchi (Okinawan languages) in classrooms using hōgenfuda (“dialect plates”), forcing students to monitor each other. In World War 2, the 1945 Battle of Okinawa withnessed brutal air raids and a ground battle – described as a “Typhoon of Steel” – that resulted in over 200,000 war deathsm including over 122,000 Okinawans – more than one quarter of the local population.

After World War 2, the United States Civil Administration of the Ryukyu Islands (USCAR) administered the islands in the face of rising political opposition calling for reversion to Japanese control. As of January 2021, approximately 70 percent of US military bases in Japan remain in Okinawa. In connection with the bases, 47,300 US military and family members live in the prefecture (Okinawa Prefecture, 2020). Since the landing of the US military in 1945, crimes including sexual assaults against women and even children have triggered strong backlash against the US military (Okinawa Times, 2016). After three servicemen sexually assaulted a twelve-year old girl in 1995, a surge of opposition rose against US militarism and the US-Japan security alliance that maintains the US military presence in Okinawa. The comments by then commander of US forces in the Pacific, Admiral Richard Macke, further enraged protesters: “For the price they paid to rent the car [in which they raped the student] they could have had a girl [a prostitute]” (Molotsky, 1995).

Authorities perceived the protests triggered by the incident as a risk to the US-Japan security alliance. In an attempt to pacify opposition, authorities announced a plan to relocate the Futenma Air Station from a densely populated central area to the remote area of Henoko, Nago City, a coastal rural community located in the northeastern part of Okinawa Island. Since then, a quarter of a century after the relocation announcement, the US-Japan alliance still maintains Futenma Air Station, while the relocation plan faces ongoing public opposition. Nago City’s 1997 referendum on the relocation plan drew over 80% of voters; of 30,900 votes cast, 52.6% opposed the construction plan (Nago City, 1997).

In August 2004, a US Marine CH-53D transport helicopter crashed into the Okinawa International University’s administration building near the Futenma base, an accident that fueled a renewed push for the removal of the base and conflict over the relocation plan. Both Nago city mayor Inamine Susumu and Okinawa Prefectural Governor Onaga Takeshi opposed the central government’s calls for proceeding with the relocation of the Futenma base to Henoko. They introduced “All Okinawa” as a key slogan for appealing to solidarity among Okinawans and contesting the expansion of US military bases within Okinawa (Ryukyu Shimpo, 2016). Meanwhile, central government officials reiterated their commitment to proceed with the plan (Yomiuri Online, 2015). Although the construction and reclamation of Ōura Bay at Henoko confronts formidable technical issues, budget overruns, and environmental destruction, the Japanese and US governments remain wedded to the plan (Lummis, 2019a; Maedomari, 2020; Yoshikawa & Okinawa Environmental Justice Project, 2020).

After reversion in 1972, the number of visitors from other prefectures to Okinawa gradually increased. The notion of the islands as “Japan’s Hawaii” became a branding tool to redevelop the area into a popular holiday destination (Tada, 2015). Okinawa Prefecture declared itself the “Tourism Prefecture (kankō rikken)” in 1995 and has since continued to emphasize tourism as its main basis for pursuing economic development. Steadily increasing numbers of visitors arrived in Okinawa each year until the current Covid-19 pandemic disrupted the industry. Before the global pandemic, annual tourists numbers reached 10 million in 2018 (Okinawa Times, 2019). However, while the industry is the core economic engine for the prefecture, scholars have pointed out how such industry inherently normalizes the landscape of US militarism as an exotic tourist experience (Figal, 2012). This paper focuses on the role of protest tourism in shedding light on this normalization, and the everpresence of militarism on the islands.

Method

This paper draws from participant observation in the protest tour, survey, and an interview with a local guide in Okinawa. Particular attention is paid to tour participant views, with observations drawn from informal interactions as well as interviews. During our first bus ride, the tour guide introduced me by saying, “She’s Okinawan. She’s from here!” One participant seated a few seats away took a photo of me as I awkwardly averted my gaze. Throughout the program, the tour members called me “Okinawa no ko” (“the Okinawan girl/kid”). It seemed to be a bit of a surprise for them to have an Okinawan student much younger than themselves attending the tour as a researcher. Yet at the same time, as an Okinawan, my presence drew attention from the participants, photographing me and wondering what made me join the tour. Hence, I became aware that I was also being observed.

The name of the tour was Ōen no Tabi (A Supporters’ Journey) and it attracted 45 participants, mainly from the Tokyo and Osaka areas. The tour’s main event was the kenmin taikai (prefectural people’s rally) in which we joined 35,000 people who gathered to demand a halt on construction of the new military base in Henoko. The tour members’ ages ranged from the fifties to the eighties, with the majority in their sixties; one third of the participants were male, and two thirds were female. The itinerary of the three-day program focused on sites relevant to militarization in Okinawa. First, we visited one of the two major Okinawan newspapers, the Ryukyu Shimpo. Then we visited the Senaga Kamejiro and People’s History Museum, which features the history of anti-military protest. Senaga, the leading politician during the USCAR administration and the reversion movement, was the Naha City Mayor in 1957 under the USCAR administration and was a member of the Japan Communist Party after Okinawa’s reversion. The rest of the trip included an excursion around the US military bases, the people’s rally, and a sit-in protest at base construction sites.

In addition to participant observation, I conducted a survey of 35 out of 45 participants. The survey includes data on age, gender, income level, number of family members, educational background, previous experiences in political activism, and prior visits to Okinawa. The survey also asked open-ended questions about participants’ feelings about the tour activities, such as “What is your most memorable experience from this tour?, “What did you learn from visiting the museum?,” and “What were your impressions of the rally?” This allowed participants to convey their personal feelings about their experiences and the deeper meaning of the tour (Yu Park, 2010). I also conducted a post-tour interview with an Okinawa-based peace tour guide who led part of the trip, traveling to military sites that had not been visited during the tour.

Galvanizing encounters

At the Ryukyu Shimpo, one journalist presented a video of a burnt building and US soldiers preventing locals from entering. A US Marine Corps CH-53D helicopter lay next to a building where it had crashed on Okinawa International University’s campus in 2004. A reporter and a camera crew had succeeded in entering the site and recording the confrontation between locals and US military from inside the damaged building. After a few moments, US forces military had attempted to confiscate the crew’s recording equipment. However, the journalist explained that the footage made it back to the office after a colleague shielded the photographer, allowing them to escape. This behind-the-scenes perspective of the accident site provided a view absent in the national media. The journalist emphasized the responsibility of Okinawan media to document the impact of militarism on Okinawan society. The footage showed the everyday operation of the US military on the archipelago, through which the military exercised direct power over locals on and off the bases. In short, the footage showed tour participants how militarism encroaches day-to-day on the lives of Okinawans on both sides of the barbed wired fence.

The tour then visited the Senaga Kamejiro and People’s History Museum, a private museum dedicated to one of the iconic figures of the post-war anti-US militarism movement. The violation of democratic processes under USCAR administration, such as forcible land grabs and failure to prosecute US soldiers who committed rape and other crimes, fueled local resentment towards the US military during Senaga’s tenure as mayor (Arasaki, 2005). Senaga was thus a key leader who boldly criticized the US military, first as the head of the Okinawan People’s Party and later as a member of the Japan Communist Party. Opened in 2013 and operated by a daughter of Senaga, the museum exhibits news articles, photos, documents, speeches, and letters of Senaga and documents the Okinawan people’s struggle against militarism and US occupation. The museum highlights Senaga’s work on behalf of reversion to Japan proceeded on the expectation that following reversion the bases would be removed and demilitarization, democratization, and an end to US rule would follow. The showcased documents, letters, and videos document US attempts to discredit Senaga by portraying him as an extremist. Despite these efforts, Okinawans remember Senaga fondly as a bold politician who stood up for their interests. The lingering theme of resistance against the US military reverberates in a speech that Senaga delivered during his election campaign:

このセナガひとりが叫んだならば、五十メートル先まで聞こえます。

ここに集まった人々が声をそろえて叫んだならば全那覇市民まで聞こえます。

沖縄の九十五万人民が声をそろえて叫んだならば、太平洋の荒波をこえて、ワシントン政府を動かすことができます

If I Senaga shout alone, it can be heard from 50 meters away.

If all of us gathered here shout as one, it can reach all the citizens of Naha City.

If 700,000 Okinawans shout as one, our voices will go beyond the rough waves and rattle Washington D.C. (Senaga, 1991, p. 75)

One section of the museum that particularly interested tour participants featured news reports documenting the ongoing protest against the construction of a new base at Henoko. The museum connects Okinawa’s current movement centered on opposition to construction of the Henoko base with the history of resistance against militarism and US occupation.

Through the lenses of journalism and political activism in Okinawa, the participants witnessed the adverse impacts of US military rule. In doing so, they gained insight into the linkage between the ongoing protest against militarism and US occupation in Okinawa. Many participants described their experiences at the newspaper and museum as “empowering.” A number of elders commented that they had mobilized in support of the Okinawa reversion movement in the 1960s. These experiences become souvenirs of solidarity through which, after the tour ended, participants would maintain empowering memories of their contact with Okinawa’s anti-militarism movement.

The authenticity of protest

On the second day, the tour attended the May 17 People’s Rally (kenmin taikai) at Okinawa Cellular Stadium, Naha City. The organizers encouraged people to wear blue clothes to represent Ōura Bay, the reclamation site for Henoko military base. A reported 35,000 people gathered in blue shirts, holding blue towels and placards. Politicians including then-Governor Onaga Takeshi, journalists, and student and community activists gave speeches opposing the construction at Henoko. The audience showed support through applause, shouts of approval, and yubibue, a loud whistle incorporated in festive performances. Most of the tour participants identified this rally as the tour’s most memorable event.

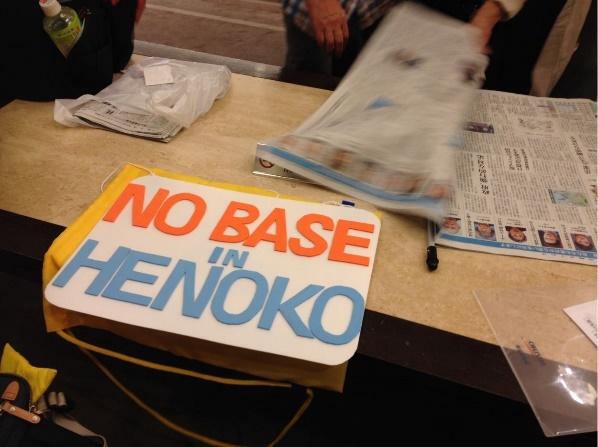

The protest provided an opportunity for tour members to participate in the protest with Okinawans. These experiences made the protest particularly meaningful to participants. Some of the tour participants brought small mascots of dugong, an endangered marine mammal that had inhabited Ōura Bay. Others brought hand-made placards. Despite the physical distance between their homes in other prefectures and the protest in Okinawa, the protest gave participants a sense of solidarity with the Okinawan people.

The rally featured Governor Onaga who greeted and thanked the audience in uchināguchi for gathering in the heat. Onaga then switched to Japanese to trace the history of US military and Japanese policies that maintain US bases on Okinawa. He concluded the speech again in uchināguchi, saying “uchinanchu usheeti naibirandō” [“You must not make fools of Okinawans”]. His brief words in a language that the Japanese government once prohibited in an effort to “standardize” Okinawans as Japanese citizens, strongly emphasized Okinawans’ identity and the struggles that distinguish them from the rest of Japan. The rhetoric of “uchinanchu usheeti naibirandō” highlights that the Okinawan identity is critical to what unites the protest. Furthermore, this emphasis on cultural identity serves as a reminder that the current concentration of US military on the islands is an outcome of repeated central Japanese government decisions that are the root of local frustration towards the US-Japan security treaty and the bases. For tour participants, words in the local language added authenticity to their experience of protest in Okinawa.

“I was able to be present at a historical moment. Being surrounded by uchinanchu [Okinawans], being given interpretation [of the speech] by them, I touched their real voice and breath. This is a scene I’ll remember for the rest of my life.” [Male participant in his 60s]

“The great fervor, passion, and solidarity of Okinawa. I was touched by many speakers including Governor Onaga, and I couldn’t stop my tears. I can tell people what I saw, heard, and felt!” [Female participant in her 60s]

The tour members’ transformative moments

People raising cards saying “Henoko New Base: No” at the rally heald at Okinawa Cellular Stadium on May 17, 2015.

Other comments indicate tour participants’ solidarity with the “Okinawan struggle.”

“I learned very well about the fight for Okinawa. I’m so touched by Okinawan people’s never-give-up spirit that I take off my hat to them.” [Female participant in 70s]

“As for the Okinawans, I hope they continue and develop their work. I wonder whether I can have a life like Kame-san [referring to a godlike Kamejiro]. (But it may be difficult for me…?)” [Male participant in 60s]

The tour provided some participants with a sense of transformation through which they recognized the problems of militarism in Okinawa as directly related to themselves. Such transformative aspects of protest tourism suggest the power of tourism as social force (Higgins-Desbiolles, 2006), as the tour allowed participants to grasp the realities of everyday militarism in Okinawa.

“I would like to show my respect for the Okinawan people. I now recognize that the big challenge is to shift the notion that the base issue belongs to Okinawa to the notion that the base issue belongs to Japan. . I hope the day of victory will come soon. I hope we can make it possible while I’m alive.” [Female participant in 80s]

“Feeling the real voice of uchinanchu and the breadth of the protest, I gained a big intellectual and emotional charge. By sharing this with my own community, I want them to feel it as our ‘own issue.’” [Male participant in 60s]

“I think seeing reality properly is the basis for understanding, so I’m glad that I attended this tour. I will take it as my own concern, think about it together with people in my community, and make it a source of my own activism. I feel that I can embrace such activities more actively in future.” [Female participant in 60s]

Furthermore, the three comments above show an interesting “shift” in their perception about US militarism, from being an Okinawan issue, to being a Japanese issue. Since the media often narrates militarism in Okinawa as an “Okinawan issue” (沖縄問題), the preceding comments indicate that the tour provided participants with an opportunity to reframe militarism as a basis for their own activism. The notion of taking responsibility for militarism in Okinawa is a necessary step for expanding anti-base activism beyond the Okinawa.

The comments further suggest that the tour facilitates better understanding of militarism than ordinary visitors would experience. The tour provided opportunities for tour members to encounter narratives often absent in national media coverage. At the local newspaper company, visitors learned of reporters’ struggles to investigate military accidents. At the Senaga Kamjiro and People’s Museum, visitors learned how Senaga advocated for demilitarization in the face of US persecution. The tour presented the uncomfortable realities of militarism on the ground being justified in the name of national security. In survey responses, tour participants expressed guilt, anger, and inspiration to continue their anti-militarist activism for Okinawa.

The military landscape

On the last day of the trip, a tour guide from the non-profit Okinawa Peace Network led the group to other US military sites throughout the island. The man, in his seventies, introduced himself as a “peace guide” and explained how he moved to Okinawa to follow his father who died while deployed as a Japanese soldier in Okinawa during World War II. At different sites, he used maps, photos, and graphs to explain the history and geography of the war and the US bases. Examining the strategic functions of each of the US bases, he challenged the classic geopolitical discourse that claims these bases enhance “security”. The narrative of Okinawa as “the Cornerstone of the Pacific” is often reinforced in the US-Japan security alliance. However, his tour revealed that the result had in fact primarily been insecurity for the local population caused by the US military.

Sites visited included the Kakazu Takadai Park, Ginowan City, where visitors can gaze over the panoramic view of Futenma Air Station and the dense residential area located right next to it. At a lookout in the park, the guide explained the progression of combat during the Battle of Okinawa and pointed to the base as one outcome of the battle. He encouraged participants to connect US military training on the base with combat in distant fields throughout Okinawa in the 1945 conflict, and the structure of US military power in Japan, Asia and beyond today. Reading the military landscape helps to contextualize the function of each base. We then visited the Kadena Roadside Station, where the municipality created an observation deck across from Kadena Air Base. We watched the vast runway from the observation deck and crossed the road to get closer to the fence. The loud noise from military aircraft repeatedly interrupted conversation.During the tour, the sound of aircraft as well as the view of the vast military infrastructure dominating the Okinawan landscape became a part of the lessons through which the guide challenged the militarization of Okinawa.

Several days after the tour members left the island, I drove with the peace guide to other sites throughout Okinawa and conducted an interview. At Camp Hansen he provided an overview of the base and the training at the firing range. He asked, “Imagine you are a soldier on the battlefield and the enemy appears in front of you, and you have a weapon in your hands. Where do you shoot?” He continued:

“Those who attend the tour often say you should aim for their heads. But if you are facing enemies in the battlefield, you would be shot while aiming for their heads. The upper body, on the other hand, offers a wider target. And other soldiers would have to care for the wounded, which further reduces their power. In this training range, the soldiers are training for war.” (Interview 2015)

Kadena Air Base during the tour, May 2015.

Kadena Air Base during the tour, May 2015.

Later, as we drove by the base, he pointed out the tanks, noting that after the US launched the Iraq war, the military changed the color of its designs from green camouflage to a light brown that better blended with the terrain of Iraq. For him, hosting tours like ours and many school trips from other prefectures in Japan helps visitors to re-conceptualize Okinawa as more than a mere travel destination. The tour guide’s work thus suggests a different way of solidarity-building in Okinawa.

My participation in the tour led me to realize how the landscape of militarism in Okinawa offers a space for educational opportunities for visitors in a way I had not previously considered. As someone who grew up in Okinawa, visitors’ reactions to the noise of combat planes, their surprise at the vastness of the military bases, and their excitement in the protests indicates the scale of militarism in the island. I found it inspirational to see a group of visitors committed to engaging with the issues of militarism during their visit. The members’ passion in studying US base issues and raising their voices at protest sites illustrated ways to expand awareness about the impact of militarism in Okinawa for people outside the islands. Protest tourism emerges as a tool that can plant seeds for a wider solidarity between Okinawa and the rest of Japan and a vehicle to pressure the government to lessen Okinawa’s military burden.

Scholarship from critical tourism studies and Indigenous studies provide additional insights. Recent critical tourism studies analyze tourism as a geopolitical tool that can be used to claim sovereignty over land (Rowen, 2014, 2016) but it can also construct national identities that conceal histories of colonialism (Werry, 2011). In Okinawa, scenes of militarism are often branded as exotic and Americanized, which romanticizes the militarized landscape (Ginoza, 2007). The contradictory functions of “security” and “paradise” are simultaneously created in many destinations while tourism glosses over a wide range of issues including militarism (Gonzalez, 2013). Although tourism could potentially stimulate political activism, there is little evidence that Okinawa’s tourism industry, any more than that of, say, Florida, contributes to demilitarization.

Moreover, the protest tour glosses over the legacies of Japanese colonialism, an omission that we can better consider by turning to recent scholarship in Indigenous studies. Ginoza (2012) argues that the relationship of US and Japanese empires are expressed in “intimate spaces of militarized Okinawa” (Ginoza, 2012). The call to critically look at the entangled political history of Okinawa, Japan, and the US at the intersection of tourism and militarism is an important reminder to think about the protest tour as a form of molding Okinawa into the colonial subject. This insight is particularly relevant to better contextualize when Governor Onaga said in uchināguchi on the day of the protest rally described earlier: “You must not make fools of Okinawans.” This statement, made in neither English nor Japanese, highlights the accumulated criticism towards the Japanese government and its taxpayers who continue bankroll the current US-Japan alliance. This usage of uchināguchi signifies the act of reclaiming an endangered language that was long stigmatized as a barrier to Okinawa’s development. Onaga’s statement evoked a range of responses. Protest tour members most appreciated hearing spoken uchināguchi as an authentic Okinawan experience. For other rallygoers, the statement was a reminder of the history of molding Okinawa into the colonial subject. The ambivalent positionality between yamatunchu (Japanese) and uchinanchu (Okinawans) emerges through the speaking of uchināguchi in the context of protest. Lastly, what the protest tour narrates as “protest” is based on a narrowly defined form of political activism in Okinawa featuring Henoko.

Protesting at the sit-in sites requires differentesources and conditions for participation, and protest rallies, too, are often occasional events mobilized with urgent and surging anger against issues related to war and militarism. While I do not question the significance of such mobilizations in the history of protest in Okinawa, it is also critical to recognize the weight of everyday resistance beyond Henoko. As the stories of everyday protest and resistance in Okinawa show (Ahagon, 1992; Chibana, 2018; Uehara, 2009), standing against militarism is deeply connected to struggles to reclaim control over the land. Everyday forms of resistance are not always about sit-ins, but rather, may celebrate the power to farm the land (Chibana 2018) or create a space to remember the violence of the Battle of Okinawa (Ahagon 1992). In other words, protest in Okinawa entails not only being anti-military but is also further about demilitarizing the land itself.

Souvenirs of solidarity

After the tour, the participants visited convenience stores to collect local newspapers that featured the rally. As we headed to a sit-in protest site at Henoko, one participant was pleased to discover himself included in a photograph from an article that showed the crowd. I develop the notion of “souvenirs of solidarity” to describe such moments that encourage the belief in a shared experience with Okinawans in the anti-militarism struggle through the tour.

Reflecting on the experience of the group, I wondered what it means to Okinawans to live so close to the US military and how many “history-turning moments” must occur before US-Japan military forces eventually leave the islands. I recognized, too, that the struggle over the Henoko base also created divisions within communities and families, particularly those whose livelihood depended on servicing the bases. A brief tour highlighting the “Okinawan fight” can only capture a snapshot of the larger struggle of mobilization against militarism.

In reflecting on the concept of souvenirs of solidarity, I wish to draw attention to the larger structural barriers that hinder demilitarization efforts in Okinawa, including contradictions between Japanese and Okinawans. Nomura and Shimabuku (2012, p. 109) boldly criticize the reality that “every Japanese person, whether of a rightist or leftist persuasion, shares the same benefits from forcing U.S. military bases onto Okinawans.” Such an analysis underlines the fact that the overwhelming majority of bases are concentrated in Okinawa, thereby freeing the Japanese in other prefectures from the necessity to live in the midst of so militarized a landscape. This could contribute toward a nuanced understanding of how US security politics create specific strategic functions for each base, allowing us to expand our understanding of the wider structures of militarism in Okinawa, Japan and beyond.

While the tour contributes to the important task of developing a critical gaze on militarized landscapes in Okinawa, the next step should be imagining what the land might look like without the fences that define those spaces. In doing so, the focus may be shifted from depicting “the militarized islands” to questioning what demilitarized islands might actually look like, and what would be required to make that possible. That ultimately will require a restructuring of the US-Japan and multilateral treaties that are the structural underpinnings of the military bases dating back to their origin in land expropriations of 1945 and continuing on, as McCormack indicates, in the structures of American and international power (McCormack, 2019). In doing so, demilitarizing the islands would also mean recognizing the damage done to the land and water, as a wide range of ecological and health damages have been reported (Mitchell, 2013, 2014, 2020).

Remapping Hawai‘i through a demilitarization tour

From this perspective, we may draw insight from a similar tour that illuminates a place-based history. On O‘ahu Island in Hawaiʻi, the US military controls almost 25 percent of the land, and a project called DeTours has been launched to reclaim the history of the land and to question US security narratives that present military bases as protectors (Kajihiro & Kekoʻolani, 2019, p. 249). Challenging the image of Hawaiʻi as a tourist “paradise,” the tour has brought more than 1,400 participants to the militarized sites often invisible in the tourist gaze. The tour features a number of places on the island such as ‘Iolani Palace, the site of the coup that overthrew the Hawaiian Kingdom (p. 251). The tour also conveys to participants a detailed history of the Ke Awalau o Pu‘uloa, known to visitors as Pearl Harbor, a powerful symbol of American security and World War 2 memory. Furthermore, the tour takes visitors to the Hanakehau Learning Farm where visitors witness how the same land provides a space to envision the future of Hawaiʻi through learning about communities and traditional farming. In so doing, DeTours highlights the history of a place where the state prioritizes militarization over the self-determination of Native Hawaiian communities and ecological concerns. Mei-Singh and Gonzalez point out that DeTours “interrupt military occupation and the poverty resulting from the theft of land and water and instead center Kanaka (a Hawaiian word meaning human being/person. The word is used to indicate indigenous people of Hawai‘i) relations to place, toward an expansive vision of Hawaiian self-determination” (Mei-Singh & Gonzalez, 2017, p. 179). This approach shifts the rhetoric of militarism from protector, to a barrier to developing local stewardship.

The example of DeTours reveals how tours can provide a useful tactic to go beyond conceiving of Hawaiʻi as the core of, or unique to, US security strategies. By illustrating the stories of the place, DeTours remaps Oʻahu not as a single destination of militarism but as part of a global geopolitical project maintained by multilateral arrangements worked out in insular territories including Okinawa, Guam, Korea, the Philippines, Australia, New Zealand, and the Marshall Islands and beyond (Kajihiro & Kekoʻolani, 2019, p. 254). The tour provides powerful counter-narratives about the islands. Moving geographical and chronological scales, from the island to the Pacific ocean as well as from annexation to militarization, the tour assists visitors in reiminaging Hawai‘i with a more contextualized and critical understanding of how militarism shapes landscapes on the ground. Furthermore, while DeTours may not involve protest tourism, the program itself challenges Hawaiʻi’s militarized landscapes. It not only tells place-based stories but also reclaims a Hawaiian way of relating to the land that contrasts with the tourism industry’s unlimited urge to capitalize the land. DeTours illustrates how tours may alter one’s understanding about the impact of militarism on the land and people as well, as revealing the powerful potential of local communities. The Okinawa protest tour invites comparison with the DeTour agenda in that participants join through a political commitment to activism and seek to deepen their understanding of the place. A major difference between the tours is that DeTour centers on Native Hawaiian perspectives while the Okinawa protest tour, while sensitive to Okinawan critiques of militarism, derives from progressive Japanese perspectives. Drawing on grassroots efforts and communities of activism in Okinawa and beyond, the protest tours have the potential to further cultivate transoceanic solidarity to address common issues of lingering colonialism and militarism.

Conclusion

Six years since the protest tour visited Okinawa to protest the new base construction at Henoko, in 2020 the construction and reclamation of the bay continues amidst the global pandemic of COVID-19, but the problems pinpointed by the tour have only grown more acute and the scheduled completion of the base is now projected not in years but at best in decades. Governor Onaga passed away in 2018, and Governor Tamaki Denny, who ran on opposition to the Henoko construction, was elected with the most votes cast in the history of gubernatorial elections in Okinawa. In a poll held in 2019 to ask people’s opinions on the construction, 73% of voters in Nago City (50.48% voting rate) opposed the reclamation of the bay (Nago City, 2019). Yet despite this and numerous other Okinawan polls revealing opposition to the new base, the Japanese government continues to insist that there is no alternative to the present dangerous base at Futenma except Henoko. It remains, in short, unmoved by the prefectural government’s and residents’ opposition. Over the years, the numbers of court cases pertaining to the construction of the base involving the national and prefectural government has grown. So too has the number of days counted at the sit-in site near Ōura bay in Henoko. Many more groups continue to visit the site, and I myself revisited it with several groups of scholars who are critical of the current situation. Protests continue on the site and in other communities since the US and Japanese governments first agreed to relocate the Futenma Air Station to the bay in 1996. While souvenirs of solidarity can be looked back on by participants, the environmental damage and scars from political struggles in Okinawa continue to grow.

4047 days of sit-in

References

Ahagon, S. (1992). Inochi koso takara okinawa hansen no kokoro.

Arasaki, M. (2005). Okinawa gendaishi. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten.

Chibana, M. (2018). Till the Soil and Fill the Soul: Indigenous Resurgence and Everyday Practices of Farming in Okinawa. (Ph.D. Dissertation), University of Hawaii at Manoa.

Figal, G. (2012). Beachheads: war, peace, and tourism in postwar Okinawa: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Fukuma, Y. (2015). “Senseki” no sengoshi: semegiau iko to monyumento: Iwanami Shoten.

Ginoza, A. (2007). The American Village in Okinawa: Redefining Security in a” Militourist” Landscape. The Journal of Social Science(60), 135-155.

Ginoza, A. (2012). Space of ‘Militourism’: Intimacies of US and Japanese Empires and Indigenous Sovereignty in Okinawa. International journal of Okinawan studies, 3(1), 7-24.

Gonzalez, V. V. (2013). Securing paradise: Tourism and militarism in Hawai’i and the Philippines: Duke University Press.

Higgins-Desbiolles, F. (2006). More than an “industry”: The forgotten power of tourism as a social force. Tourism management, 27(6), 1192-1208.

Kajihiro, K., & Kekoʻolani, T. (2019). The Hawaiʻi DeTour Project Demilitarizing Sites and Sights on Oʻahu: Duke University Press.

Lummis, C. D. (2019a). “It Ain’t Over ‘Till It’s Over”: Reflections on the Okinawan Anti-Base Resistance. The Asia-Pacific Journal Japan Focus, 17(1).

Lummis, C. D. (2019b). We’re Not So Good at Running…But We Still Know How to Sit: On The Political Culture of Okinawa’s Anti-Base Sit-In. The Asia-Pacific Journal Japan Focus, 17(23).

Maedomari, H. (2020). Okinawa Demands Democracy: The Heavy Hand of Japanese and American Rule. The Asia-Pacific Journal Japan Focus, 18(16).

McCormack, G. (2019). Irresistible Force (Japan) Versus Immovable Object (Okinawa): Struggle Without End? The Asia-Pacific Journal Japan Focus, 17(23).

Mei-Singh, L., & Gonzalez, V. V. (2017). DeTours: Mapping Decolonial Genealogies in Hawai’i. Critical Ethnic Studies, 3(2), 173-192.

Meyer, S. (2020). Between a Forgotten Colony and an Abandoned Prefecture: Okinawa’s Experience of Becoming Japanese in the Meiji and Taishō Eras The Asia-Pacific Journal Japan Focus, 18(20).

Mitchell, J. (2013). Herbicide Stockpile at Kadena Air Base, Okinawa: 1971 US Army report on Agent Orange. The Asia-Pacific Journal, 11(1).

Mitchell, J. (2014). Tsuiseki okinawa no karehazai umoreta senzso hanzai wo horiokosu (K. Abe, Trans.): Koubunken.

Mitchell, J. (2020). PFAS Contamination from US Military Facilities in Mainland Japan and Okinawa. The Asia-Pacific Journal, 18(16).

Molotsky, I. (1995, 11/18/1995). Admiral Has to Quit Over His Comments On Okinawa Rape. The New York Times.

Nago City. (1997). Nago shi ni okeru beigun no heripoto kichi kensetsu no zehi wo tou shimin tohyo. Nago City Office,.

Nago City. (2019). Henoko beigun kichi kensetsu no tameno umetate no sanpi wo tou kenmin tohyo kaihyo jokyo sokuho.

Nomura, K., & Shimabuku, A. (2012). Undying Colonialism: A Case Study of the Japanese Colonizer. CR: The New Centennial Review, 12(1), 93-116.

Okinawa Prefecture. (2018). What Okinawa Wants You to Understand about the U.S. Military Bases.

Okinawa Prefecture. (2020). Okinawa no beigun oyobi jieitai kichi (tokei shiryo shu).

Okinawa Times (Producer). (2016, July 11, 2016). 米兵の性犯罪、赤ちゃんも被害 「暴力の歴史」続く沖縄.

Okinawa Times. (2019, 11/21/2019). Jitsuwa 1000 mannin koeteita okinawa kanko kyaku su. ken wa hokoku more kizuiteita. 8 gatsu gejun niwa haaku. Okinawa Times.

Rowen, I. (2014). Tourism as a territorial strategy: The case of China and Taiwan. Annals of Tourism Research, 46, 62-74.

Rowen, I. (2016). The geopolitics of tourism: Mobilities, territory, and protest in China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 106(2), 385-393.

Ryukyu Shimpo. (2016, July 10, 2016). 沖縄選挙区は伊波氏が当選確実 現職大臣の島尻氏落選 衆参6議席「オール沖縄」独占. Ryukyu Shimpo. Retrieved from

Senaga, K. (1991). Senaga kamejiro kaiso roku: Shinnihon Shuppansha.

Steinhoff, P. G. (2013). Memories of new left protest. Contemporary Japan, 25(2), 127-165.

Tada, O. (2008). okinawa imēji wo tabisuru. yanagita kunio kara ijū būmu made: chūo kōron shinsya.

Tada, O. (2015). Constructing Okinawa as Japan’s Hawaii: from honeymoon boom to resort paradise. Japanese Studies, 35(3), 287-302.

Uehara, K. (2009). Contesting the “Invention of Tradition” Discourse in the Pacific Context:-Significance of “Culture” in the Kin Bay Struggle in Okinawa and the Kaho ‘olawe Movement in Hawai ‘i. Immigration Studies,(5), 67-86.

Werry, M. (2011). The tourist state: Performing leisure, liberalism, and race in New Zealand: U of Minnesota Press.

Yomiuri Online. (2015). 菅官房長官「粛々と」に沖縄知事「上から目線」. Yomiuri Online. Retrieved from

Yoshikawa, H., & Okinawa Environmental Justice Project. (2020). The Plight of the Okinawa Dugong. The Asia-Pacific Journal Japan Focus,, 18(16).

Yu Park, H. (2010). Heritage tourism: Emotional journeys into nationhood. Annals of Tourism Research, 37(1), 116-135.