Abstract: Having arrived in France in 1921, the young student of French, Komatsu Kiyoshi 小松, 清, made the acquaintance of Ho Chi Minh. While briefly noting Komatsu’s career as litterateur through the French Popular Front years, this article brings to light the nature and depth of Komatsu’s relationship with Ho Chi Minh, especially as revealed by French police documentation. Komatsu’s links with communist and anarcho-syndicalist networks in Paris – Japanese included – and his surprising memoir of Ho Chi Minh published in a Hanoi newspaper in 1944 casts new light on both men and the relationship between Vietnam and Japan.

Keywords: Komatsu Kiyoshi, Ho Chi Minh, Paris, Hanoi, anarcho-syndicalism, anti-French nationalism

Having arrived in France in late 1921, the young Kobe-born student of French, Komatsu Kiyoshi 小松, 清, made the acquaintance of Ho Chi Minh then going by the name of Nguyễn Ái Quốc, ushering in a relationship with France and Vietnam that practically spanned his entire life in controversial and ambiguous ways. While Komatsu is well known today in Japan as a pioneer translator into Japanese of André Gide and André Malraux, this article especially draws attention to Komatsu’s correspondence with Ho Chi Minh in Paris and other little-known activities recorded in French archival records. The article raises a series of questions as to the depth of Komatsu’s relationship with Ho Chi Minh, his links with anarcho-syndicalist and communist circles in France, his suspected relationship with the Japanese Legation in Paris, and his surprising remembrance of the man he knew as Nguyễn Ái Quốc as serialized in a Hanoi newspaper in 1944 at a time when his whereabouts or even livelihood was practically unknown to French intelligence services. But that is not all, as the enigmatic Komatsu was then himself based in Hanoi in the employ of Japanese intelligence, inter alia charged with grooming a Vietnamese counter-elite to that of the local Vichy French regime in Vietnam. Witnessing the Japanese military coup de force of March 1945 against the French, as well as the historic August Revolution, and staying on in Vietnam for another year, Komatsu claimed to have met Ho Chi Minh, now President of the newly-installed Democratic Republic of Vietnam. It remains to explain, then, Komatsu’s abrupt conversion from Francophile leftist to champion of militarist Japan’s Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere project and, in another turn of the wheel, his apparent active support in favor of Vietnam’s communist revolution at the moment of Japan’s capitulation.

Komatsu’s Arrival in France

As profiled by the French police, Komatsu was born 13 June 1900 in the port city of Kobe. He held a Japanese passport issued in Kobe and was issued a visa by the French consulate in this city on 23 July 1921. From Komatsu’s published diary, we know that as a young student in the Kobe Prefectural Commercial Junior High School from which he graduated in March 1918, he studied English at a YMCA night school. Entering the Kobe Commercial High School, he additionally took up Esperanto in his spare time. Up until September 1919 when he quit the school, he started his writing career by contributing articles to a local literary circle. Early 1920 saw him adrift in Tokyo but awakened by experiencing a May Day rally at Ueno Koen. While initially contemplating study in the United States, but drawing negative attention to himself owing to a critical article he published in a newspaper of the day, in mid-1921 his well-connected uncle in Kyoto helped him to gain a passport and to redirect his attention to France (Furansu chishikijin to no kōryū Tōkyō, 2010, p.580) [hereafter, Komatsu Collected Works].1

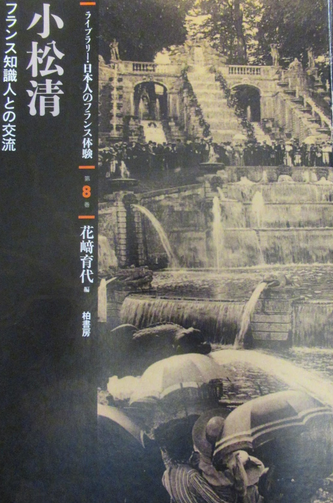

フランス知識人との交流 Furansu chishikijin to no kōryū (French Intellectual Exchange), 2010

Setting out from Kobe on 31 July 1921 on a Nihon Yusen line vessel, he arrived in Marseille via Colombo on 17 September 1921. Initially putting up in a local “artist village” with compatriot artist Aoyama Kumaji, he then moved on to Paris where he immediately made contact with the artist, Sakamoto Hanjirō (坂本 繁二郎), whom he had met on the sea voyage from Japan and who preceded him to Paris. Sakamoto, in turn, occupied an apartment rented by Kojima Torajiro (児島虎次郎) who, as described in a French police report, was “a somewhat celebrated artist who had since returned to Japan.” That was correct. Kojima, who first arrived in Paris in 1908 had returned to Japan but, in 1920, revisited Paris at which time he associated himself with the artist Monet and the French impressionist school. After several weeks residing in Sakamoto’s apartment, Komatsu rented his own place in the same building (at 18 Rue Ernest Cresson in the 14th arrondissement or district), and it was during this interval that he first made contact with Ho Chi Minh (ANOM HCI SPCE Correspondances entre le Ministère des Colonies et le Gouvernement général 364).2

Unknown to Komatsu, he immediately attracted French police attention upon arrival in Paris (and possibly even the moment he stepped off a ship at Marseille). For that matter, he may have aroused suspicion of the French authorities back in Kobe at the time he applied for a visa, especially given his youthful background and apparent socialist associations (Morgan 2013: 4). That in itself would not have been a major issue with the French authorities, but France was wary of Japanese support for exiled Vietnamese anti-colonial agitators, as with the literati Phan Bội Châu and the royal prince, Cường Để. In 1910, France had successfully sought their expulsion from Japan but Cường Để’s return and high-level political sponsorship literally became a major irritant in Franco-Japanese relations through the entire interwar period (Tran My-Van 2005). Ironically, both Ho Chi Minh and Komatsu would engage Cường Để later in their careers although in contradictory ways (namely, with Ho Chi Minh rejecting Cường Để’s royal nationalism and with Komatsu playing the prince’s anti-colonial nationalist card alongside Japan, as exposed below.

Ho Chi Minh in Paris

The new peace in Europe in the aftermath of World War I found many stay-behind colonials in the major capitals. In France they included a number of former worker-soldiers from Indochina, Madagascar and the Arab countries, along with Chinese and other nationalities stranded in France and with some putting down roots through marriage, work, or as students. By 1920, they would be joined by newly arriving contingents of officially sponsored student-workers, mostly Chinese but including smaller numbers of Korean and Thai students. First coming to French police attention in Paris in June 1919 under the name Nguyễn Tất Thành, after some six years of travels from his native Vietnam including time in the Americas and England, Ho Chi Minh met some of them even though he was not formally a student and was obliged to work for his living (Lacouture 1968; Duiker 2000; Brocheux 2000; Quinn-Judge 2002; Ruscio 2019; Gunn 2021a).

Ho Chi Minh’s primary networks in Paris were undoubtedly his compatriots and much has been written about the support he received from the time of his arrival in the French capital from the Groupe des Patriotes Annamites, notably the veteran anti-colonial activists, Phan Châu Trinh and Phan Văn Trường (and with both implicated in anti-state activities), and the students Nguyễn Thế Truyền and Nguyễn An Ninh. Nguyễn Tất Thành, who would join them, having taken on the persona of Nguyễn Ái Quốc (not yet firmly identified by the French authorities). Collectively, the group was known as the “five dragons.” Either as editors or collaborators they also assisted him in the production of his famous Revendications, the petition calling for Indochina autonomy which he submitted in June 1919 to the French National Assembly and to delegates of the Paris Peace Conference (formally opened on 18 January 1919 at the Quai d’Orsay).

To be fair, a full portrait of the then 25-27 year-old Ho Chi Minh cannot be drawn without examining the intellectual and political influences of his early contacts with a range of French individuals associated with the French Socialist Party and, subsequently the French Communist Party (FCP). Nevertheless, despite the abundant literature on Ho Chi Minh in Paris, far less attention has been devoted to yet another circle or network to which he related, namely other colonials, including members of the Korean and Chinese delegations to the Peace Conference (Gunn 2021b).

Engaging Ho Chi Minh

No sooner had Komatsu arrived in Paris (likely around 13 October 1921) than he attended a meeting at which Ho Chi Minh participated and likely addressed. Evidently engaging Ho in conversation at the event, Komatsu then volunteered to provide him with information on trade union activities in Japan. But which conference or event? If we examine Ho Chi Minh’s schedule for September-December, he was always busy. Mornings he worked as a photo retoucher at a studio adjacent to his rented room in a working-class district on Rue Compoint, evenings often saw him at meetings hosted by a spectrum of socialist or revolutionary groups, or busy with the newly created Union Intercoloniale, an organization bringing together Africans, Madagascans, West Indians along with Vietnamese, or at private meetings with his compatriots especially at their Villa de Gobelins residence near Place d’Italie (also near Zhou Enlai’s then abode) (see Goebel 2015). Even so, between late 1919-23 he spent every spare moment in Parisian libraries researching the political economy of colonialism with special reference to French Indochina but with a secondary interest in colonialism in general including Japanese colonialism in Korea (Ruscio 2019).

In fact, as Komatsu recalled in later life, the event that brought him together with Ho Chi Minh was the occasion of a grand rally attended by prominent politicians of the Left (Marcel Cachin of the French Communist Party included) in support of two Italian-American anarchists, Sacco and Vanzetti, implicated in a murder case but widely believed to have been railroaded owing to to their politics. This took place at the historic Salle Wagram auditorium [Komatsu Collected Works], a fact confirmed by Jean Lacouture (1968: 22), who asserted that it was there that Ho Chi Minh “tapped him on the shoulder.” The event and the date (Sunday 23 October 1921) is also recorded by the senior French police agent in charge of surveillance of Ho Chi Minh. As he noted, Ho Chi Minh and two Vietnamese compatriots attended “a demonstration organized by revolutionary parties, anarchists, and trade unionists” to protest the death sentence imposed in the United States on the two anarchists (ANOM HCI SPCE 364 Notes confidentielles des agents du Service des renseignements; Note de M. Devèze du 26 Octobre 1921). One of the two other Vietnamese attending the meeting that day was the Le Havre-based militant anarcho-syndicalist seaman, Lê Văn Thuyết (Leon), who frequently stayed up in Ho Chi Minh’s apartment when visiting Paris. Although there is no specific record, most likely Komatsu’s attendance was observed by French police agents.

The next most likely occasion on which Komatsu could have heard Ho Chi Minh speak publicly in the month of October 1921 was at a Saturday session of the Club de Faubourg. Hosted by the Club president and socialist journalist, Léo Poldès, Ho Chi Minh had been taken under his wing to overcome his shyness and to polish his oratorial skills. He was a frequent attendee. Debates ranged across a spectrum of topics from hypnotism to socialism. The meeting of Saturday 15 October 1921 commenced at 2:30 p.m. The venue was the Théâtre de Press, rue Montmartre 125 (actually opposite the editorial office of the communist newspaper L’Humanité). The title of the debate was “Communisme contre Colonialisme. Le problem, noir, la question jaune, la solution communiste.” As billed, there were four speakers, three from the Republic of Haiti and Nguyen Ai Quoc from Indochina” (Ruscio 2019: 126). The topic was a drawing card on this day and the audience for these Saturday events usually exceeded 100 persons. The next major public event which Ho attended that year was on 17 November. Again, the occasion was a debate hosted by the Club de Faubourg, at 127 Av. de Clichy on the topic of whether or not doctors were charlatans (ANOM SLOTFOM XVI 1921). However, as explained below, Komatsu had been ill that entire week.

Failed Rendezvous and Letter Apology

At their meeting on 23 October, the two obviously set up a rendezvous because, on 19 November 1921, Komatsu sent a letter to Ho Chi Minh addressing him as Nguyễn Ái Quốc. In this, he apologized for failing to keep an appointment owing to a severe case of the flu threatening pneumonia. He also alluded to a manuscript on the “worker’s party of Japan” which he wished to deliver. Explaining that for the past eight days he had been confined to an apartment with no heating, no water, and no company, and that he was obliged to go outside to fetch his own food and medicine, it sounded like a plausible excuse. As he explained, given the winter conditions in Paris and his malady, he intended to back off to the south of France – Cannes, Manton or Nice – and find employment as a laborer. Then followed some platitudes about “work” and life, nature and the human condition and the creation of a new society in Russia and the East. “Mon cher camarade,” the letter concluded, “je vous prie de me dire la plus tôt possible de quel manière je puis me procurer une carte de communiste” (Please tell me as soon as possible how I can acquire a communist [party] card) (ANOM HCI SPCE 364 13 Décembre 1921).

Komatsu also offered the postal address of 18 Rue Ernest Cresson in the 14th arrondissement, not far from the Cimetière Montparnasse. By all appearances – even today – a solidly upper middle-class neighborhood, it was still an eight-floor walkup. In making this pitch, Komatsu obviously sought to ingratiate himself with Ho Chi Minh (yet they were hardly equal whether as workers or as committed communists). For that matter, Ho was not in the best of health himself and, likely tubercular (his boss sought to evict him on those grounds). As French police agents observed, at times he was reduced to eating a piece of bread dunked in soup. His shabby rented room in a working-class district likewise lacked heating.

Nevertheless, after some two months in Paris, on 4 December in the company of two other compatriots, one Nogura, and the other, Inosuke Hazama (硲 伊之助), both then residing at 17 Rue Sommerand, an elegant abode adjacent to the Sorbonne, the three departed Paris together with the intention of seeking out a warmer climate in the south of France. On his part, Inosuke lived and studied in France from 1921 to 1929 and again in the years 1933-35, during this second sojourn studying with Henri Matisse. As explained below, they may well have wished to avoid the crowds in Paris at a time when the memory of the devastating Spanish Flu was still recent. At the time, the French authorities understood that Komatsu would return to Paris in the spring (ANOM HCI SPCE Correspondances entre le Ministère des Colonies et le Gouvernement général 364).

According to an official report authored by the Ministry of Interior, there was nothing negative to remark about Komatsu during his two-month stay in Paris. He held an identity card issued by the Prefecture of Police and was otherwise unknown to the police and judicial services. He studied French and made good progress. Nothing in his conversations hinted at any attraction to communism. This in itself – or his reticence to speak out – the report estimated, may have attracted some reservation on the part of his compatriots. On the other hand, as the police surmised, he may indeed have been an agent of the Japanese Embassy in Paris, which could explain why he wished to contact Ho Chi Minh and obtain a communist party membership card. Accordingly, the letter he addressed to Nguyễn Ái Quốc might be treated with some skepticism. For that matter, the severity of his purported sickness might also be questionable (ANOM HCI SPCE 364 Correspondances entre le Ministère des Colonies et le Gouvernement général, 13 Décembre 1921). From this report, it is clear that the authorities themselves were perplexed as to the true meaning of this letter and that they really had no clear answers. Regardless, Komatsu was now under surveillance by the French authorities. But unlike the thousands of French colonials then in Paris and with many under surveillance for their anti-colonial attitudes, Komatsu himself was a non-French colonial.

Interlude in Nice

According to Komatsu’s diary, following their first meeting, Ho Chi Minh introduced him to the FCP-affiliated Comité des études coloniales. But even if Komatsu followed up this suggestion, it is likely that his illness prevented him from a deeper commitment that winter (nor would he follow it up later) (Komatsu Collected Works). Having moved to Nice in December 1921, Komatsu made contact with a local FCP branch and it was through a FCP connection that he found employment nearby Nice on an Italian-owned farm as gardener (more or less as alluded in his letter to Ho Chi Minh). This was at Villa St. Philippe, Av. Candia (today, Estienne d’Orves), on the high ground overlooking the Mediterranean. During free time he also kept in contact with Japanese artists residing in the Nice area. Still in contact with the FCP in Nice, he evidently clashed with some local party members (Komatsu Collected Works, p.578), but he still cannot have burnt his bridges.

Komatsu as Suspect in the Emperor Khai Dinh Assassination Plot

Returning to Paris from the south of France in the spring of 1922, in May Komatsu connected with the Clarté literary circle founded by famed antiwar writer Henri Barbusse who, together with writer Raymond Lefèvre and Ho Chi Minh-ally in the FCP, Paul Vaillant-Couturier, formed a left-wing group called L’Association républicaine des anciens combattants (ARAC). Komatsu did not immediately meet Barbusse but was in contact with Magdeleine Marx, militant feminist-communist, a former visitor to Moscow who was then serving as ARAC’s secretary. She offered Komatsu a job as messenger “boy.” The summer of 1922 found Komatsu putting up in a cheap apartment on Rue Cujas, a street in the 5th arrondissement near the Sorbonne (Komatsu Collected Works). The Clarté circle, with its premises at 16 rue Jacques Callot within walking distance of Rue Cujas, was well known to Ho Chi Minh as well and he could have set up the introduction. In April 1922, the radical anti-colonial newspaper that Ho had just established, namely, Le Paria, initially shared office space with Clarté.

A month later Komatsu once again came under close surveillance. This was at a time when Khai Dinh, the Emperor of Annam (r.1916-25), was visiting France. Although totally unfounded in every respect, the authorities linked Komatsu to Ho Chi Minh and a group of Vietnamese in a plot to assassinate the emperor coinciding with his visit to the Exposition Coloniale at Marseilles. Inaugurated on 16 April 1922 by Minister of Colonies and former Indochina Governor General, Albert Sarraut, as a celebratory post-war event to commemorate the triumph of France’s empire – as with its replica Rue de Hanoi or Palais de Madagascar – the authorities sought to prevent any disturbance to its success.

Besides penning critical press pieces on the French protectorate of Annam, on 11 June 1922 Ho Chi Minh successfully staged a theater piece he wrote titled, Le Dragon de bambou, a spoof on the visit to France by Emperor Khai Dinh. The venue was Théâtre de la Presse, rue Montmartre, and the host was the intellectual circle, the “Club de Faubourg.” This would have been another occasion where Komatsu could have met Ho Chi Minh and, if so, such an encounter would certainly have been witnessed by French police agents. That would also help to explain why, scarcely twelve days later on the night of 23-24 June 1922, all the Vietnamese suspects (Ho included), along with Komatsu, were placed under close police surveillance.

Putting up at a hotel on 4 Quai de Billancourt, Komatsu was absent that night and only returned at 2 p.m. the following day. He was then tracked by French police agents as he walked along the banks of the Seine and dined with some compatriots in the hotel – presumably the artist group – followed by another promenade. The concerned Vietnamese placed under surveillance that day were Phan Văn Trường and Nguyễn Thế Truyền (as introduced), close Ho Chi Minh associate Lê Văn Thuyết (Léon) (as introduced), Tran Tien Nan, a student in the Faculty of Law (rue Saint Jacques); Vo Ban Doan, apparently involved in the photography business, and another unidentified Vietnamese. On his part, Nguyễn Thế Truyền was tracked through various Left Bank locales including the Bibliothèque St Geneviève, billiard parlors, etc; Lê Văn Thuyết, was shadowed to Ho Chi Minh’s address in Rue Compoint although failed to meet him; and with Ho Chi Minh kept under surveillance all that morning at his workplace, in the afternoon at the editorial office of “Le Journal du Peuple,” organ of the Parti socialiste SFIO, although lost sight of later in the day in the Boulevard des Italiens owing to the traffic. On his part, Vo Ban Doan was trailed to Place d’Etoile where the visiting Emperor of Annam had placed a plaque to honor the Unknown Soldier. There, he asked questions as to where the emperor was staying prompting even closer police surveillance throughout the day (ANOM HCI SPCE 364 Note de la Prefecture de Police de 20 Juin 1922. “Surveillance exercée à l’egard d’Annamites et Japonais suspecte.”)

In other words, five weeks off the ship, still a student of French and barely 21 years-old, Komatsu came to be associated with the most notorious circle of anti-colonial radicals and suspected anarchists then in Paris, including the authors of the famous petition to the Paris Peace Conference and founding members of the French Communist Party following the Tours Congress of December 2020 – Ho Chi Minh included – which voted in favor of the Third International and its support of the Bolshevik revolution. Although Ho Chi Minh himself eschewed anarchism, that was unknown to the authorities and anarchism was still a current embraced by some Vietnamese as with earlier bomb outrages in Hanoi and the future failed assassination attempt against French Indochina Governor General Martial Merlin in Canton in 1924.

Ho Chi Minh himself went on to publish articles mocking Khai Dinh’s visit as in a two-page piece in Le Journal de Peuple (9 August 1922), comparing the emperor to “a colonial artifact” brought to France to be presented at the Colonial Exposition at Marseille, and one “kept in a display case for some two months like an exhibit so as not to deteriorate.” In trenchant verse, he asked the emperor to look beyond Pasteur, Voltaire, Victor Hugo and Anatole France and to open his eyes to the rights of men. He went on to denounce the luxuries surrounding palace life with its opium, its women, and its eunuchs. There may have been no lesé majesté law in France but back home the mandarins whom he lambasted were also taking note of his transgressions (as with his endorsement of rebel activities against the state) leading him to subsequently attract a death sentence from the Court of Annam.

Second Return to the South of France and the Marseille Plot

From French police sources, it is apparent that by August 1922, Komatsu had drifted apart from Ho Chi Minh. He was no longer attending meetings of the Comité des études coloniales. In November he moved again to the Paris suburbs staying with the artist Maeda Kisaburo. With winter setting in, they planned to relocate to the south of France.

On 7 December 1922, French police Agent Jolin once again drew attention to Komatsu. The context was the presence in Marseille of Chua Hai, a Vietnamese worker-specialist engaged by the French air force during the First World War. Marseille was also the port of arrival and departure of Vietnamese and other colonials and, at any time there was a large group of employed and unemployed immigrants. It also came to French police attention that Chua Hai was among a delegation of Asians at St. Charles Station in Marseille to welcome the arrival of a Japanese going on to Nice or Cannes. As surmised, this person could only have been Komatsu or the artist Maeda or another unknown Japanese (and with Komatsu’s address identified as Villa St. Philippe in Nice). On his part, Chua Hai was suspected to be the person behind a distribution of La Tribune Annamite, an anti-colonial newspaper published in Paris (ANOM HCI SPCE 364 Note de Agent Jolin, Marseille, 7 Décembre 1922). After all, Komatsu had a record of association with communists and suspected anarchists and the authorities never lost interest in him.

By the new year of 1923 Komatsu together with Maeda found accommodation in Antibes on the Côte d’Azur, and with Komatsu staying there through to November. Tragically, in February, Maeda died. He was just 22 years old, and likely a victim of the Spanish flu (but this is speculation)? That month Komatsu received a letter from his sister back in Kobe learning, inter alia, of a difficult family economic situation (perhaps also advising him to look after himself). Keeping up his leftwing connections, namely via the Nice branch of ARAC, the following month Komatsu met at Miramar for the first time with Barbusse (Komatsu Collected Works, p.579). He was now securing his literary contacts.

Dalliance with Osugi Sakae

In April Komatsu traveled together with artist Hayashi Toshio to Lyon where he met the notorious anarchist Osugi Sakae (大杉 栄) (Komatsu Collected Works, p.580). Unknown to himself, Hayashi was already under French police surveillance and the Japanese authorities were likewise alerted as to Osugi’s presence in Europe. Osugi had arrived in Marseille by ship from Shanghai on 23 January 1923 moving on to Lyon and Paris where he connected with anarchist circles, Chinese included, and with Hayashi known to Osugi as an “old comrade” from the Syndicalism Research Group formed in Tokyo in 1913. The two then moved to Lyon where he spent most of the month of April (and it was during this period that Komatsu joined him). But May Day 1923 found Osugi in Paris addressing a rally in support of the Italian-Americans, Sacco and Vanzetti, only to be arrested and detained (Stanley 1976: 226). Following a judicial process – in which he was defended by a leading communist lawyer – on 23 May he was issued a deportation order and was freed from detention (Peletier 2002: 112-14). However, bereft of a passport, he accepted the advice (order?) of Japanese Embassy officials to return to Japan via Marseille on a Japanese passenger ship bound for Kobe. It defies logic that Osugi contrived in his own “extradition” especially as the Japanese Embassy in Paris had its own interests. Nevertheless, as he subsequently explained in his memoir as initially serialized in Japanese newspaper articles, he also had family concerns in Japan, and so had little choice but to accept the invitation or “order” (Osugi 1923). As is well known, two months after returning to Japan he was dead in Tokyo, murdered (Stanley 1976: 229; anon, Libero International, 1978).3 The events concerning Osugi in France, at least, were undoubtedly known to Komatsu – indeed reported in the local French and international media. Likely, as well, he learned of Osugi’s death on 16 September. In fact, he must have been shocked. But what linked Komatsu with Hayashi and Osugi in the first place? Was it an Esperanto connection at the time Komatsu first visited Tokyo in early 1920 or did they meet at the May Day rally that year at Ueno Koen, or was the connection via one or other of the “anarchist-artists” then in France?

In November 1923 Komatsu settled into Antibes where he secured a job as clerk in a Japanese art-craft boutique named “Yamato-ya” and he would stay on there through 1925 painting, writing and, likely, securing and broadening his literary contacts (Komatsu Collected Works).4 In any case, it would be another 20 years before Komatsu resurfaced in French police files (as far as we know). As explained below, this was a time when Komatsu was deputy head of propaganda in the Japanese setup in Hanoi at the moment the Viet Minh took power.

Envoi

Returning to Japan in 1931, Komatsu began to translate and introduce the works of Malraux and Gide, obviously a major labor. According to Vinh Sinh (2001: 64), a scholar who first introduced Komatsu’s wartime activities to a Western audience, Malraux was “nothing short of a living model” for Komatsu in combining political activism with art at a high level (and with Malraux himself seemingly influenced by Komatsu when it came to characterizations of Asians in certain of his literary productions). From Japan in 1934 Komatsu boldly launched his Nouvelle Ecole de l’Humanité de l’Action et de son Esprit or Action Literature movement, which he engaged through the journals Kōdō (Act), Kōdō bungaku (Action Literature), and Kanrin (Academy) (see anon: France-Japon, January 1934, p.206). Later in life, as Komatsu (1960: 115) explained of this ultimately doomed initiative given the rise of militarism and suppression of liberal and radical thought:

About the year 1935, motivated by my activist humanist feelings, I joined a movement which promoted such ideas as anti-fascism, the Popular Front and the defense of culture in Japan. I had secretly planned to introduce to the world of Japanese journalism the same sort of movement which was being developed in France, and to make of it a living force. In that sense I could be said to have been one of the seed-sowers or igniters of the fire of the Popular Front in Japan.

Returning to Paris in 1937, he became a correspondent for the Hochi Shinbun (報知新聞) while also working for the French monthly information magazine France-Japon. Fleeing France ahead of the German invasion he arrived back in Japan in 1940. Still prior to the outbreak of the Pacific War, he made a trip to Vietnam arriving in April 1941. Returning to Japan the following month, he was arrested and detained for suspected socialist connections (Vinh Sinh 2001: 68-69, 71; Komatsu Collected Works, p.562).

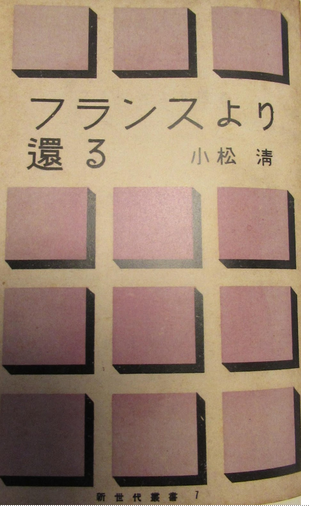

フランスより還る (育生社), Furansu yori kaeru (Return from France), 1941.

The Komatsu Conversion

More than a few on the Left in Japan during this period including those who had earlier embraced Moscow underwent ideological about-turns – or tenkō (転向) – often after spells of imprisonment. Komatsu appears to be one, otherwise how can we explain his abrupt change of career? Having gained his liberty, Komatsu sought to demonstrate his usefulness to Japan’s Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity project, just as Japan drastically needed French-speaking diplomat-agents of Komatsu’s caliber. At this point, he first made contact with the rebel Prince Cường Để then back in Japan and allied with the Japanese-backed Đại Việt party active in northern Vietnam via its military wing. Evidently making contact with top-level military and/or diplomatic circles in Tokyo, in 1943 he was dispatched to Hanoi in the capacity of advisor to the Nihon Bunka Kaikan (Japan Institute of Culture), a branch of Japan’s diplomatic intelligence services (Nitz 1984: 12; Marr 1997: 84n59). As alluded, Indochina was then under Vichy French cohabitation with the Japanese military at a juncture when Japan was seeking to propagandize its “Co-Prosperity Sphere” by succoring anti-French Vietnamese nationalists, winning over religious sects, sowing division, advancing Japanese language and cultural activities, promoting Asian brotherhood, and advancing its anti-white agenda. We should not underestimate the importance of Komatsu at this juncture.

As Vinh Sinh (2001: 57-86) explains, Komatsu was probably the Japanese most widely associated with Vietnamese intellectuals from north to south, as with future Republic of South Vietnam strongman, Ngô Đình Diệm, the southern French-educated intellectual and eminence gris of the southern Viet Minh, Dr Phạm Văn Bạch. At the same time, by associating himself with the Đại Việt party, Komatsu became entangled in what François Guillemot (2009) terms the “temptation ‘fasciste‘” of Đại Việt’s anti-colonial struggle. While Komatsu may have been “somewhat autonomous” vis-à-vis the military as Namba (2002: 234-35) has asserted, it is hard not to see him as “a propaganda agent” in the service of Japanese Ambassador Yokoyama Masayuki such as described by American OSS agent Archimedes Patti (1980: 304).

The tenor of this remark is confirmed by French intelligence sources, a reference to the key intermediary role that Komatsu performed in succoring a pro-Japanese-anti-French counter-elite. As Komatsu made known in an interview published in a Saigon newspaper in May 1945, having moved to the southern city in late 1943, he took up with Matsushita Mitsuhiro, head of Dainan Kōshi. 大南公司, a long-established trading company in Saigon, and with Matsushita himself a key figure in Japanese intelligence in southern Vietnam, especially in serving as a go-between with Prince Cường Để and other anti-French nationalists (Tachikawa 2001: 102-03). According to plan, as Komatsu recounted, he made contact with the nationalist scholar, Trần Trọng Kim and his scholar associate, both then residing in a “safe house” on the outskirts of Saigon-Cholon, and would be in close contact with the pair for over a one month period pending their sudden departure for Bangkok (to avoid arrest by the French). The date was 1 January 1944 at a time when Komatsu was making a side trip to Phnom Penh (likely another intelligence activity). Described in the article as an “historic house,” another tenant was Ngô Đình Diệm with whom Komatsu also bonded. As Komatsu himself learned by letter, in the wake of the Japanese coup de force against the Vichy French in Indochina in March 1945, Trần Trọng Kim returned from Thailand, made his way to the imperial capital of Hue and was installed as the head of the pro-Japanese government where he duly formed his cabinet “as confirmed by His Majesty (Bảo Đại)” (MAE Asie-Oceanie 1944-1955 Indochine 161 “Indochine: L’Indépendence de Viet-Nam; Extrait articles de la review Thong Tin, May 1945).5 Passed over in appointments, Ngô Đình Diệm was still not out of the picture. For what ever reason, however, Komatsu’s other ally, Prince Cường Để was simply dumped and died in April 1951.

Still in official service, Komatsu not only witnessed the military coup de force against the French in March 1945, but also the sequential Japanese capitulation five months later, the communist “August Revolution,” and the installation of Ho Chi Minh as president of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam on 2 September. Staying on in Vietnam for a total of four years until April 1946 (somehow avoiding immediate repatriation and war crimes charges), he reportedly met Ho Chi Minh one more time. This was in September 1945 (date unspecified) and the venue was the headquarters of the Provisional Government of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (Komatsu Collected Works, p.594). In doing so, he may also have been seeking credit for what French intelligence believes was his active role in assisting Japanese to desert with their arms to the Viet Minh cause (Gunn 2014: 209).

Komatsu as Writer/Translator

As remembered in Vietnam today, during his early Hanoi period Komatsu translated into Japanese a French-language version of Nguyễn Du’s 18th century Vietnamese classic, Tale of Kieu,soon after the first French translation appeared. Working with the help of the Vietnamese journalist and translator, Nguyen Giang, known to him from Paris days, this work was published in Tokyo in October 1942 under the title 金雲翹 阮攸 (Namba 2002: 234). Again, with Giang as translator, Komatsu worked on a partly autobiographical novella looking back on his early months in Paris. Commencing on 25 June 1944, this was serialized in 30 issues of the Hanoi newspaper, Trung Bắc chủ nhật (North Central Sunday) (from 25 June 1944 to 1945 (no. 208 to 237) or spanning nearly seven and a half months, and published under the title, Cuộc tái ngộ (the Reunion).

As described by Namba (2002: 237), this was a novel portraying the life of an unnamed Vietnamese in France who took on a nationalist persona and returned to Vietnam. His communist identity is muted to meet the expectation of Vichy (and Japanese) censors. It is of no small interest that, in 1996, Tạp chí Xưa & Nay (Past and Present Journal), brought this obscure work to public attention. A publication of the Vietnam History Association, as minutely analyzed by David Marr (2000), the journal then went as far as possible in expanding the parameters of historical debate inside Vietnam.

According to Tạp chí Xưa & Nay (Past and Present Journal) (No. 27, May 1996: 21), the author’s view and explanation of the characters in the story are based on real facts… ” As Komatsu reveals in one vignette of Cuộc tái ngộ (the Reunion):

… in the spring of 1921 I went to France and on to Paris… I remember, fifty days after arriving in Paris, by accident, I met a young Vietnamese in a public meeting place. That young Vietnamese man was the first Asian with whom I hung out with in a long time in France.

… I can tell you right away that this Vietnamese was such a respectable, worthy, even outstanding person.

Back then we did not have the same direction. Our conceptions of life, literature, and many other things were not the same. Especially in terms of cultural ideas, we were somewhat far apart. Our opinions at times were fiercely contradictory. We were young, it is not easy to yield to each other. . . although we had a real difference, that young Vietnamese always left in my heart a sincere respect, because I know more than anyone, that my friend was always faithful to his will and his thoughts. Moreover, there were many practical actions that clearly demonstrated that he was committed to a life of service. My friend is really a patriot, no matter what hardship he has had in his life, his patriotism is demonstrated.

That man worked as a wage earner for his living, and you could not imagine how much he suffered. He ate very little, slept very little, worked a lot. Every afternoon, when he had finished hard work in the factory, he sat at the desk to write or read a book. How, damn it! His body was then being ravaged by a terrible disease, practically incurable. His eyes were often lit up by the shady fever seeping inside. Sometimes he coughed up as if he was about to stop breathing. Yet, his spiritual life was still plentiful and rich, his activities were still incessant. Two or three times, I had the opportunity to hear him speak in front of a French audience in French, very fluent, eloquent words. He worked as an assistant writer for many daily newspapers and weekly newspapers in Paris, sitting at home writing articles and sending them regularly.

As the account continues, although becoming friends, after the first meeting, visiting and talking with the character, the author (Komatsu) and his Vietnamese friend had little chance to meet again. Komatsu went to the south of France to live in seclusion, and his Vietnamese friend left France for northern Europe (Germany and Russia). But Komatsu kept up with the news of his friend and believed in him.6

More recently, the issue has been taken up on official Vietnamese websites in various versions. For example, adumbrating upon the Tạp chí Xưa & Nay article, writer Thuý Toàn affirms the veracity of the story, noting that it was matched by historical documents along with Vietnamese and French publications. As he recaps it, Komatsu first set foot in France in August 1921 with the intention of becoming an artist. In Paris, he shared a house with painter Sakamoto and another Japanese – the three having chanced to meet on the way from Japan to Marseille. Komatsu’s rented room was in the attic of an eight-floor building near the Montparnasse cemetery. Just as Komatsu mentions in Reunion, it was there that Nguyễn Ái Quốc first visited Komatsu [and, if true, it would resonate with Komatsu’s storyline]. Likely, the article speculates, Komatsu started translating Nguyễn Du’s Tale of Kiều because he was influenced by Ho Chi Minh/Nguyễn Ái Quốc. This is possible if the two discussed Vietnamese or any other genre of literature since Ho Chi Minh was then considerably better read than Komatsu in classical as well as modern world literature, indeed Ho was his senior or mentor on just about any subject except Japan. As with his theatrical production staged in Paris, Le Dragon de bambou, Ho Chi Minh also adroitly employed allegory in his political writings.

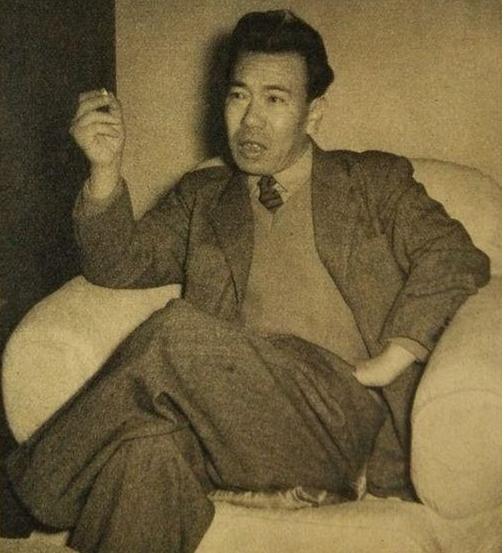

Komatsu Kiyoshi, 1954 (Source: Wikimedia Commons).

Conclusion

Although we are led to believe by Komatsu’s own writings that he enjoyed a special and unique relationship with Ho Chi Minh in Paris, the truth possibly lies elsewhere. They met briefly in a public venue along with other Asians. They exchanged letters, but neither apparently followed up the correspondence. In his writings Komatsu alludes to mutual visits to each other’s apartments, yet that figures in no French police reports. Ho Chi Minh was entirely pragmatic in his friendships and networks. He was then drafting articles on Korea and possibly Japan. He lacked resources on the working class in Japan. Komatsu obviously knew more, but could not have had statistical material or other concrete data, such as Ho Chi Minh perhaps naively had hoped. Moreover, Komatsu made a perplexing demand, namely to join the French Communist Party. As noted, the French authorities responded to Komatsu in two ways. One stream of opinion believed that he was in league with the Japanese Legation in Paris as well as the Consulate in Marseille and therefore was some kind of agent (a view that cannot be dismissed in the light of his future career). But another stream – the police – condemned him by association with Ho Chi Minh for involvement in a dark anarchist conspiracy – namely the presumed plot to assassinate a Vietnamese emperor. In fact, there was no such plan, and it is ironic in the extreme that Komatsu would later associate himself with a rebel prince of the House of Annam.

It might have been thought that the tone of Komatsu’s initial letter put Ho Chi Minh on guard as to his sincerity or motives, indeed of his maturity. But that does not appear to have been the case. There was one more exchange of letters. This is known because on 30 January 1922, writing from Nice, Komatsu responded to a letter from Ho thanking him for concern about his health (ANOM SLOTFOM XVI Le Gouveurneur général de l’Indochine, Hanoi, 20 Février 1922 “surveillances des annamites”).7 This was very generous of Ho Chi Minh. Possibly unknown to Komatsu, Ho also suffered from “la grippe” that winter – a term then used to describe the Spanish Flu. Although examined at the Cochin Hospital on rue du Faubourg-Saint-Jacques, he was not hospitalized. He was, however, extremely busy attending a communist congress in Marseille between 25 and 30 December 1921 (ANOM SLOTFOM XVI Note de Agent Désiré, 9 Janvier 1922). He made no apparent attempt to contact Komatsu during that visit and, indeed, that appears to have been the end of their correspondence, at least as recorded in French police and administrative files. Again, it is speculation but, at a time when the rift between anarcho-syndicalists and communist circles in France was becoming increasingly strained, Ho Chi Minh may well have been alerted to the depth of anarchist influences among the Japanese circle in Paris, Lyon, and possibly the south of France, with the Osugi trial and deportation a negative example.

As noted earlier, Nguyễn Ái Quốc had completely disappeared from French police records since his release from a British prison in Hong Kong ten years earlier (and believed by many to be dead). His journey back to China from Moscow was unknown (Gunn 2021a Chap.9). Nevertheless, from mid-1941 French intelligence had possession of a virulent anti-French-anti-Japanese tract signed by Nguyễn Ái Quốc dated June 1941 and written in Chinese. As translated, this read: “Nous nous révoltons, toute la nation se révolte contre les Français et les Japonais” (We are revolting, the whole nation is revolting against the French and the Japanese). Effectively, it announced the creation in May 1941 in the Chinese border village of Tsing Tsi of the “League of Independence for Viet Nam” (or Viet Minh). They were also cognizant of an individual named “Ho Chi Minh” active in the Yunnan/Guangxi sector although the connection between him and Nguyễn Ái Quốc had not yet been confirmed (ANOM HCI SPCE 370 Commandement supérieur des troupes françaises en Extrême-Orient: presse, bulletins et notes de renseignements, tracts, articles et discours de Hô Chi Minh 1941-1949). In August 1942 Ho Chi Minh was arrested close to the Vietnam border and held in a series of Chinese Nationalist prisons in Guangxi over a fourteen-month period until released in September 1943. Then and only then did he resume his clandestine activities in Yunnan, this time assisted by the American Office of Strategic Services in their joint project of collecting intelligence information on Japanese military activities.

Did Komatsu gain wind of Ho Chi Minh’s presence in Guangxi or southern Yunnan from his Japanese military intelligence patrons? Why at this moment in his literary career did he pen such a cloying if nostalgic literary piece about a communist-nationalist? Was he hailing the return of a nationalist messiah? As an individual who spent half of his life associating with radical causes, how can we explain his evident tenkō back in Japan soon after his flight from France under threat from Nazi Germany? Once installed in Vietnam, how did he fit Cường Để and the Đại Việt party into the picture? Ultimately, was he prepared to play any anti-French card, communist or royalist? These are not easy questions to answer nor, indeed, are explanations of Komatsu’s interest in French Indochina in the first place. Somehow, out of all these contradictions, his status as litterateur and humanist remains secure in Japan today together with some rehabilitation – or recognition – in official Vietnamese circles as with the Tạp chí Xưa & Nay (Past and Present Journal) circle.

A version of this article was originally published in Keiei to Keizai [Faculty of Economics, Nagasaki University] (Vol. 100, No. 4, March 2021, pp.83-113).

References:

anon. 1934. France-Japan: Bulletin mensuel d’information.

anon. 1978.”Ôsugi Sakae in Paris,” Libero International, No.5, September.

anon. 1996. “a Japanese writer wrote about Nguyen Ai Quoc while in France,” [in Vietnamese] Tạp chí Xưa & Nay, (25), pp. 13–15; (26), pp. 17–18; (27), pp. 19–21.

Brocheux, Pierre. 2000. Ho Chi Minh, Presses de Sciences Po, Paris.

Duiker, William J. 2000. Ho Chi Minh: A Life, Hyperion, New York.

Goebel, M. 2015. Anti-Imperial Metropolis: Interwar Paris and the Seeds of Third-World Nationalism, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Guillemot, François. 2009. “La tentation «fasciste» des luttes anticoloniales Dai Viet, Nationalisme et anticommunisme dans le Viêt-Nam des années 1932-1945,” Vingtième Siècle. Revue d’histoire, Vol. 104, Issue 4, pp.5-66.

Gunn, Geoffrey C. 2014. “’Mort pour la France’: Coercion and Co-option of ‘Indochinese’ Worker- Soldiers in World War One,” Social Science, Vol.42, No.8, pp.63-84.

___________, 2014. Rice Wars in Colonial Vietnam: The Great Famine and the Viet Minh Road to Power, Rowman & Littlefield, Lanham, MA.

___________. 2021a. Ho Chi Minh in Hong Kong: Anti-Colonial Networks, Extradition and the Rule of Law, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

___________. 2021b. “Between Theory and Praxis: Ho Chi Minh’s Parisian Networks, Intellectual Productions and Evolving ‘Thought,'” Journal of Contemporary Asia, Vol.51 (in press 2021).

Komatsu Kiyoshi. 1941. フランスより還る (育生社), Furansu yori kaeru (Return from France), iku seisha, Tokyo.

___________, 2010. フランス知識人との交流 Furansu chishikijin to no kōryū, Vol. 8. Kashiwa Shobō, Tokyo. (Reprint originally published: Tōkyō : Kaizōsha and Ikuseisha, 1940-1941, with new introd.).

Komatsu, Kyo, and Midori H. Scott. 1960. “A JAPANESE FRANC-TIREUR TALKS WITH GIDE AND MALRAUX.” The Centennial Review of Arts & Science, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 115–143.

Lacouture, Jean. 1968. Ho Chi Minh: A Political Biography, Random House, New York.

Marr, David G. 1995. Vietnam 1945: The Quest for Power, University of California Press, Berkeley.

___________. 2000. “History and Memory in Vietnam Today: The Journal Xua & Nay,” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. 31, No. 1, pp. 1-25.

Morgan, Joseph G. 2013. “A Meeting in Tokyo: Komatsu Kiyoshi, Wesley Fishel, and America’s Intervention in Vietnam,” Journal of American-East Asian Relations, Vol. 20, No. 1, pp.29-47.

Namba, Chizuru. 2012. Français et Japonais en Indochine (1940-1945). Colonisation, propagande et rivalité cultural, Karthala, Paris.

Nitz, Kyoku Kurusu. 1984. “Independence without Nationalists? The Japanese and Vietnamese Nationalism during the Japanese Period, 1940–45,” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. 15, No. 1, 108-133.

Ôsugi Sakae. 1923. Nippon Dasshutsu Ki, ARS, Tokyo.

Pelletier, Philippe. 2002. “Ôsugi Sakae, Une Quintessence de l’anarchisme au Japon,” Ebisu, n°28, pp. 93-118.

Ruscio, Alain. 2019. Ho Chi Minh écrits et combats, Le Temps des Cerises, Paris.

Quinn-Judge, Sophie. 2002. Ho Chi Minh: The Missing Years, 1919-1941, University of California Press, Berkeley.

Patti, Archimedes. 1980. Why Viet Nam?: Prelude to America’s Albatross, University of California Press, Berkeley, CA.

Schauerte, Michael. 2014. My Escapes from Japan, Doyosha, Tokyo.

Stanley, Thomas Arthurs. 1976. “Osugi Sakae: A Japanese Anarchist,” Ph.D. thesis submitted to the University of Arizona Press.

Tachikawa Kyoichi, “Independence Movement in Vietnam and Japan during WWII,” The National Institute for Defense Studies (NIDS) Security Reports, No.2, March 2001, pp.93-115.

Thuý Toàn. 2012. Chuyện ít biết về người đầu tiên dịch “Truyện Kiều” sang tiếng Nhật

“Nhà văn Nhật Bản đầu tiên dịch “Truyện Kiều” của Nguyễn Du là bạn anh Nguyễn ở Paris, 6 December 2012 Little-known stories about the first person who translated “Tale of Kiều” into Japanese,” 21 February 2012. hoa/Chuyen-it-biet-ve-nguoi-dau-tien-dich-Truyen-Kieu-sang-tieng-Nhat-329686/

Tran My-Van. 2005. A Vietnamese Royal Exile in Japan, Prince Cuong De (1882-1951), Routledge, New York.

Vinh Sinh. 2001. “Komatsu Kiyoshi and French Indochina,” Moussons, 3, pp.57-86.

Notes

Volume 8 of a multi-volume collection of Komatsu’s works, namely, Furansu chishikijin to no kōryū Tōkyō, offers a useful introduction and a timeline of his early life in Japan and activities in France from which I have drawn. Nevertheless, it does not carry Komatsu’s own memoir or writings on his early stay in France.

ANOM (Archives nationales d’outre-mer, Aix-en-Province); SPCE (Service de protection du corps expéditionnaire); HCI (Haut commissariat de France pour l’Indochine).

This was Osugi Sakae, Nippon Dasshutsu Ki (ARS, Tokyo, 1923). See the translation by Michael Schauerte My Escapes from Japan (Doyosha, Tokyo, 2014). Osugi does not mention meeting Komatsu but does allude to Hayashi returning to his place of abode in the south of France.

Without citing a source, Jean Lacouture (1968: 43) asserted that in November 1923 or just prior to leaving for Moscow, Ho Chi Minh invited Komatsu to come along with him, albeit with the latter declining. Yet, this seems highly unlikely given Ho Chi Minh’s penchant for secrecy as well as the seeming break in their relations.