In this collection of essays our authors explore a range of issues not covered in Part 1, examining the broader impact of the Olympic Movement, efforts to spin the message and whether hosting the games is worth the extravagant costs. Two authors focus on the Paralympics, another presents excerpts from a graphic guide to the Olympics while others delve into previous Olympics, what they represented and how they influence the 2020 games. There are also several essays on opposition to the Olympics and lingering concerns about how the government has managed the Fukushima nuclear accident. The COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic casts an ominous shadow over the games,, amid concerns that Prime Minister Abe is sacrificing public health through inaction and minimizing risks in order to save the Olympics.

PR Meltdown

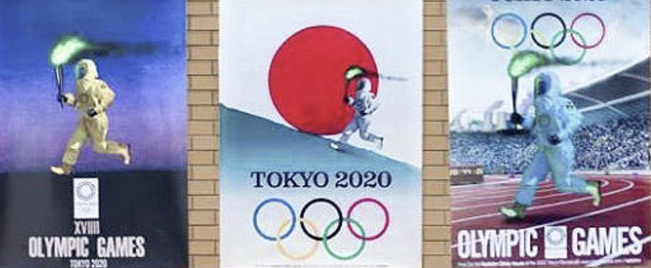

There are several essays on opposition to the Olympics and lingering concerns about how the government has managed the Fukushima nuclear accident. These concerns are shared in South Korea where a civil group has put up posters depicting an Olympic relay runner wearing a hazmat suit carrying a radiation spewing torch. The Japanese government is also incensed that South Korea maintains a ban on Fukushima seafood imports, and that the WTO has ruled in Seoul’s favor. Prospects of this becoming the “Reconciliation Olympics” thus seem remote as the governments spar over unresolved grievances from their shared history.

From “Olympics minister denounces South Korean posters of Tokyo 2020 torch runner in a hazmat suit,” Japan Times, Feb. 14, 2020.

In terms of PR, always a key consideration for Olympic branding, does it really make sense for the Japanese government to shift the limelight to where it least wants it? Martin Fackler, former New York Times bureau chief in Japan, commented: “Did you see the Olympics Minister (Hashimoto Seiko) criticized those posters? What a dumb, dumb move. Criticizing those posters on an international stage (as Olympics minister of the host nation) just gives them more traction. And then framing it as a Japan-Korea dispute? This just deprives Japan of any moral high ground it might have had by turning this into a tribal dispute.” (personal communication Feb 15, 2020) He adds, “I have seen Japan bumble like this so many times over the years. The underlying problem is that the other arms of government, including the PM Office, rely on the Gaimusho to run international PR. The diplomats have no idea what they’re doing, and see overseas media through the lens of their ability to sway domestic media. They also pursue institutionally defined outcomes that are unrealistic, sub-optimal, and ultimately self-defeating.”

Now Japan’s inept spin-doctors face a new test, but don’t seem to be doing any better as the international media has widely condemned the sluggish public health response by PM Abe Shinzo’s government at a time when the stakes couldn’t be higher.

Pandemic?

Covid-19, the coronavirus that has spread across China and more than four dozen other nations including Japan, casts a long shadow over the prospects for the Tokyo 2020 Olympics. On February 24th, Dick Pound, a senior member of the International Olympic Committee (IOC), warned that cancellation or postponement of the games might be necessary if the outbreak is not contained by the end of May.

He suggested cancellation is more likely than postponement due to various scheduling conflicts, so with only three months until this ‘deadline’, time is getting tight. The Olympics have only been cancelled 3 times and all during wartime—due to WWI in 1916 and in 1940 and 1944 due to WWII. In 1940, Tokyo was the selected hosting city, but due to Japan’s war in China it renounced its rights in 1938 and then the alternate site Helsinki was engulfed in war. The Rio Olympics, however, were held as planned in 2016 despite the Zika virus outbreak.

The IOC, Japan Olympic Committee (JOC) and the Japanese government have been insisting that the games will not be cancelled, postponed or relocated. Yet doubts have mounted as, the Japanese authorities botched quarantine of the cruise ship Diamond Princess, and an overall woeful crisis response, has not inspired confidence.

Health care workers emerging from the quarantined Diamond Princess in Yokohama

Numerous sporting events in China and across the region have been cancelled as have large conventions, but none are in the same league as the Olympics. From July 24-August 9 this megaevent will feature 11,000 athletes (and thousands of support staff) competing in some two hundred events that will attract tens of thousands of fans, ideal conditions for transmission of the coronavirus if the outbreak is not contained before then.

It doesn’t help that former Olympian Kawabuchi Saburo who serves as honorary mayor of the Olympic Village where athletes are housed, asserted that Tokyo’s hot and humid summer would stop the virus. He stated, “The virus is susceptible to humidity and heat. In Japan, we have the rainy season which could defeat the virus.” Perhaps, but under the circumstances it is hard to imagine that this reassurance will quell concerns.

The stakes are high as the 2020 Games are supposed to be the crowning achievement of Abe’s tenure. There are also financial concerns. According to AP journalist Stephen Wade, the IOC’s total revenue from 2013-2016 was $5.7 billion. He estimates this total revenue at $6 billion for the 2017-2020 cycle. (Personal communication Feb 14, 2020) Add to that an estimated $28 billion spent by Japan to prepare for the games and it is understandable why officials involved have their fingers crossed that this pandemic will pass sooner than later. If not, there is the option of postponing by one year, but again, any deviation from the current schedule presents major headaches for a range of vested interests not to mention the athletes.

Torch Symbolism

The Olympic torch relay is scheduled to begin on March 26 in Fukushima’s J-Village, a sports training facility that served as a staging ground for efforts to manage and mitigate the nuclear disaster following three reactor meltdowns in March 2011. Doing so aims to reinforce the official message that the situation is under control. Yet, as several of our authors contend, that view is contested and many residents in Tohoku, the region devastated by the tsunami, resent the diversion of resources to support the “Reconstruction” Olympics at their expense. Back in 1964, the torch relay began in Okinawa at a time when it was still under US military administration, a reminder of Japan’s sovereignty, and ended in Tokyo where the cauldron was lit by a Hiroshima native born on August 6, 1945, the day the atomic bomb devastated the city and its’ inhabitants . Symbolically, the 1964 torch relay sent pointed reminders while in 2020 it seems to be more about forgetting issues of ownership and nuclear legacies etched into the collective memory. (Jacobs 2016)

Photo Credit: Andy Marks, Fukushima August 2019

In closing I want to express our gratitude to the editorial team at The Asia-Pacific Journal Japan Focus — Mark Selden, Yayoi Koizumi, Joelle Tapas and Connor Griffin –for their support and hard work in bringing this project to fruition.

References:

Jacobs, Robert, 2016. “On Forgetting Fukushima”, The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 14, Issue 5, No. 1, March 1.