Abstract: At the 1964 Tokyo Olympics the Japanese women’s volleyball team, nicknamed the ‘Witches of the Orient’, defeated the Soviet Union to win the gold medal. This article charts the story of the Witches journey to the Olympic final and draws parallels with the post-war growth of men’s rugby in Japan and the performance of the national team the ‘Brave Blossoms’ at the 2019 Rugby World Cup. As in 1964, the Tokyo 2020 Olympics will showcase Japanese technology, creativity, culture and hospitality, but will also highlight the necessity for greater acceptance of diversity in Japanese society through the power of sport.

At the 1964 Tokyo Olympics the Japanese women’s volleyball team, nicknamed the ‘Witches of the Orient’, defeated the Soviet Union to win the gold medal. The volleyball final, played on the evening of 23 October, a day before the closing ceremony, remains one of the highest rated broadcasts in Japanese television history, and was a victory that, for the Japanese people, epitomised the success of Tokyo 1964. This article charts the story of the Witches and their journey to the Olympic final, noting the legacy the gold medal victory had for the growth of sport for women in Japan. It then draws parallels with the post-war growth of men’s rugby in Japan and the performance of the national team the ‘Brave Blossoms’ at the Rugby World Cup in 2019, noting the recent inclusion of rugby as an Olympic sport and set to be popular at Tokyo 2020.

|

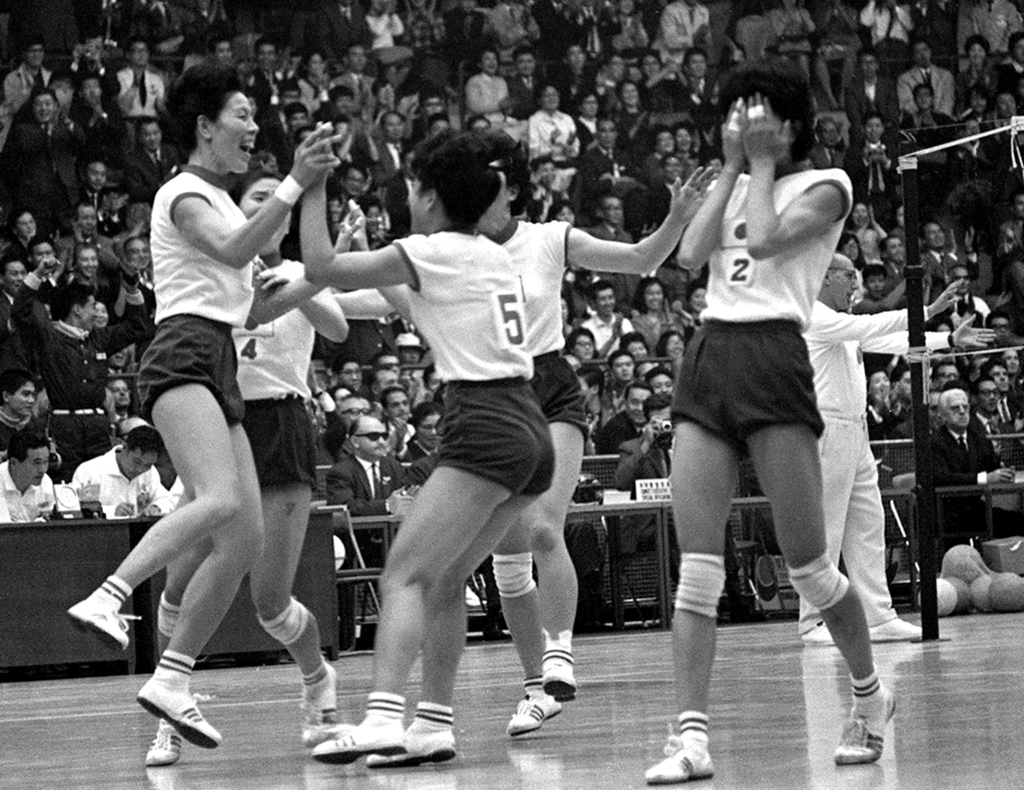

The Witches of the Orient win gold at the Tokyo 1964 Olympics. Kasai, the captain, is far left jumping in the air. Photo courtesy of Kyodo News. |

From corporate team to Olympic team

Volleyball as a sport was growing in popularity after the Second World War, not only in Japan but worldwide. The International Volleyball Association was established in 1947, and the world championships were held the first time for men in 1949 and for women in 1951, but at this time limited only to European countries. A decade later, in 1959, the International Olympic Committee decided that men’s volleyball was to be an Olympic sport, so in 1960, Japan for the first time sent both a male and female team to the world volleyball championships, held that year in Brazil. The Japanese men’s team took eighth place, but the women’s team unexpectedly won second place in the world competition. This Japanese women’s team, rather than being a national team, was in actual fact a corporate team from a Japanese textile manufacturer, Nichibō, at that time the strongest women’s team in Japan as winners of the domestic national volleyball championships. The Japan Volleyball Association had been unable to fund two teams to go to Brazil in 1960 and so had encouraged Nichibō to fund their women’s team’s trip to the world championships to see what the international competition level was like. After winning second place in Brazil, Nichibō subsequently decided to send the team on a European tour in 1961, where they went on to play and win 24 consecutive games (Sawano 2008). In the following year, the world volleyball champions were hosted in Moscow, with the Nichibō team once again representing Japan, and in a surprise upset beating the Soviet world champions in the final. The captain of the Nichibō team was Kasai Masae. She was 29 years of age when the team became world champions in Moscow, and she was ready to retire. However, earlier that year, in April 1962, it had been announced that women’s volleyball would be an Olympic event for the first time at the Tokyo 1964 games, so following their victory in Moscow, Kasai and her team mates came under intense pressure from media and fans across Japan not to disband their winning team and aim for the Olympics. In an interview I had with Kasai in 2012, she recollected that she felt that the public at that time would not allow her to retire, and that the only way to respond to mass expectation that the team could win the gold medal was to try to give them that victory (Macnaughtan 2012, 497). In the subsequent selection of Japan’s women’s volleyball team for the 1964 Olympics, 10 out of 12 players were chosen from the Nichibō corporate team, and Kasai was chosen as captain.

The magic of the Witches and the Olympic final

During their European victories in 1961-62, the team was given the nickname the Witches of the Orient (Tōyō no Majo) by the mass media, which was an allusion to the trickery and magic of their play (Merklejn 2013). The Nichibō team had been coached by Daimatsu Hirofumi since 1953, later selected as Olympic team coach, who became famous for his notoriously strenuous training regimes, and nicknamed ‘Demon Daimatsu’ (Oni no Daimatsu) by the Japanese media. The magic play of the Witches included several never-before-seen techniques devised by Daimatsu, including a signature move known as ‘rotating receive’ (kaiten reshību). Conscious of the difference in physical stature between the Japanese and USSR women’s teams, Daimatsu believed that agility and speed were the key to defeating the Soviets, and the move was likened to a judo move in nature, whereby a player received the ball without touching their bottom on the floor and then rotated immediately into a defensive position. In the build-up to Tokyo 1964, Daimatsu’s training regime steadily gained national and international attention, documented in a short film that won Grand Prize at the 1964 Cannes Film Festival. In his own publications Daimatsu reflected that his training regime was indeed harsh, but commented that volleyball was not about physical techniques alone and required a ‘fighting spirit’(konjō) (Daimatsu 1963). This fighting spirit culminated in an Olympic final that captured a record television viewing audience of 85% of Japanese (Macnaughtan 2014; Tomizawa 2019).

As the Olympics progressed in October 1964, the Japanese public were buoyed by medal results, particularly in judo, athletics and wrestling, but on the afternoon of 23 October a Japanese judo competitor expected to win the gold medal was defeated by a Dutch competitor. This increased the pressure for winning a gold medal in the women’s volleyball final, which was scheduled for later that same day. By late afternoon, people and taxis were disappearing off the streets across Japan, and the telephone switchboard operated by Nippon Telegraph and Telephone Corporation almost ground to a halt, as everybody rushed to be near a television set to watch the final of the women’s volleyball. To say that a gold medal was expected from the Japanese team was an understatement. One of the team members had commented anxiously the previous day that, ‘if we lose, we might have to leave the country’ (Macnaughtan 2014, 145). Such was the public expectation and pressure mounting for the players. At 7pm that evening, the excitement emanating from the Komazawa indoor sports hall in Tokyo was broadcast on televisions across Japan. The Japanese and the Soviet teams arrived on the court. With Soviet players as tall as 184 cm, they looked a physically imposing presence vis-à-vis the Japanese team, with Kasai the tallest Japanese player at 174 cm. The Japanese team won the first two sets decisively: 15–11 and 15–8. In the third set they were leading 13–6, but then as the pressure of winning the gold became closer to reality they began to lose points consecutively. When the score reached 14–13, Daimatsu requested a time-out to talk to his team. After play resumed, the Japanese served the ball and an over-the-net foul from a Soviet player secured the elusive 15th point and served up Olympic history. The 4,000 spectators in the auditorium leapt up with thunderous applause, while the six players on the court stood shocked for a moment then cried and embraced each other (Macnaughtan 2014). This final match was, in the end, a decisive victory for Kasai and her team, winning in three straight sets. It was the end of a journey that had taken them from playing the sport as young employees in a corporate team to representing their nation. For Kasai and her team mates, this journey had not been as easy as that victory might suggest. Kasai later recalled the moment the whistle blew in that final match, and her teammates cried and came to hug her. She describes how she was choked with deep emotion, and filled with tears but that she tried not to cry ‘until her mission as team captain finished’ (Kasai 1992, 90). While receiving the gold medal in the awards ceremony and watching the Japanese flag being raised with the national anthem being played, she felt very emotional and moved, and very glad that she had been able to meet the expectations of the Japanese people. She records that, if she had quit two years previously as intended, she would not have felt that deep emotion nor received the gold medal, and was happy that she had made the decision to continue (Kasai 1992, 90-91). Daimatsu and Kasai formed a celebrity sporting partnership that captured the nation’s attention, and the story of the Witches has been reignited in Japan during the build up to Tokyo 2020. Kasai passed away in October 2013 aged 80 years, making my interview with her in May 2012 one of her last. At the end of that interview she reflected on the impact Tokyo 1964 had on her life (Macnaughtan 2012, 499):

“The gold medal changed my life a lot. My subsequent 48 years have been a really happy life. Many people who watched TV that day and cheered for the volleyball team in the Olympics have now passed away. But I am still remembered by a lot of people when I attend volleyball classes and activities all over Japan. The fact that the Olympics were held in Japan had a huge impact. People all over Japan watched the games on TV. Even people who didn’t have a TV watched them somewhere. The viewing rate of our final match is still unbeatable. It has been 48 years since then, but I am still recognised everywhere – in the train, on the streets or in the department store. I’m very grateful. I think that I am the luckiest volleyball player in the world.”

It is well known that the Tokyo 1964 Olympics was historic, as the first Summer Olympics not only in Japan but in Asia. The Witches’ gold medal victory symbolised the end of a successfully hosted Games by Tokyo, that also served to herald Japan’s arrival back on the international stage after their Second World War defeat as a peaceful and technologically modern nation, and would come to be known as the ‘Happy Olympics’. Tokyo 1964 was the first Olympics to incorporate women’s team sports including volleyball, so the Witches victory was historic as the first gold medal in women’s volleyball in Olympic history, as well as Japan’s first gold medal in a women’s event for 28 years (Kietlinski 2011). The popularity of volleyball, particularly as a sport for women, grew immensely in Japan in the decades following 1964. Particularly influential, and a legacy of the Witches victory, was the spread of the sport to women of all ages in Japan, notably the establishment of ‘mother’s volleyball’ (mamasan barēbōru). Previously the domain of young women, after the 1964 victory, volleyball became an acceptable and accessible sport for older, married Japanese women (Takaoka 2008). Kasai commented in an interview that, prior to the Olympics, Japanese housewives (shufu) concentrated on housework and looking after children, reflecting that it was ‘unthinkable’ that a housewife would engage in sports or have a job or hobbies outside the home. After the Olympics, however, women of all ages were inspired to take up the sport and mother’s volleyball clubs sprung up across Japan. Even today, volleyball remains one of the most popular sports for Japanese women, and helped inspire other mothers’ sporting clubs particularly in softball, basketball, football and even rugby. In fact, the story of the Witches offers some parallels to the history of the growth of rugby in post-war Japan.

Rugby and the Olympics

Rugby union was a men’s sport at the Summer Olympics early in its history, played at the 1900, 1908, 1920 and 1924 Games, but was discontinued thereafter. However, the seven-a-side version of rugby made its Olympic debut at the 2016 Rio Games, and with the growing popularity of the sport in Japan, particularly with Japan’s hosting of the 2019 Rugby World Cup (which like Tokyo 1964 was billed as the first in Asia), rugby looks set to be a popular event at Tokyo 2020. The Japan men’s rugby sevens team will no doubt be aiming for a medal at Tokyo 2020 after losing the bronze medal match at Rio 2016, and will be hot on the heels of the growing strength and popularity of the national rugby union team. Nicknamed the ‘Brave Blossoms’, the team made history in 2019 by reaching the Quarter Finals at the Rugby World Cup hosted in Japan, thereby becoming the first Asian nation to top their group and the first Asian team to progress to the knockout stages in the history of the competition. While the rise of Japanese rugby might seem meteoric, the sport has been played there since 1866 (Galbraith 2016), and Japan has qualified for every Rugby World Cup since the competition’s inception in 1987. Japan has long been the strongest rugby union power in Asia, and the Japan Sevens team has also competed in the various international rugby sevens competitions since their inception; the Hong Kong Sevens series founded in 1976, the Rugby World Cup Sevens founded in 1993 and the World Rugby Sevens Series founded in 1999.

Similar to the story of the Witches volleyball team, the development of rugby in postwar Japan has strong origins in corporate teams. The All Japan Company Championship was established in 1948, and is the precursor to the current Top League competition that has been running since 2003. There are 16 rugby teams in the Top League, all bearing corporate names. This development of corporate rugby teams was spearheaded by companies in Japan’s manufacturing sector, particularly iron & steel, automobiles and electronics, a reflection of the power of these manufacturing sectors in the postwar economy, as well as the dominance of male employment (Macnaughtan 2019). As in the textile industry, where female employment dominated, sports teams were initially established for factory employees to encourage exercise, wellbeing, team spirit and teamwork. However, with the growth of national rugby competition from the 1960s, Japanese corporate rugby teams began to recruit top players upon graduation from Japanese university teams and invest in the sport itself as well as utilize their teams for CSR and company branding (Fukuda 2010). In recent years, there has also been a significant growth in the recruitment of non-Japanese players by the Top League teams, particularly from Asia-Pacific rugby playing nations. The Brave Blossoms national team selects players from the Top League corporate teams, and the growing ethnic diversity of the Blossoms team has captured media attention, contrasting with Japan’s image as a homogenous nation (Guardian 2019a).

For players, switching between the fifteen-a-side and the seven-a-side game is difficult, but switching between the games could increase now that rugby is in the Olympic Games. In an historic first for the Rugby World Cup, eighteen Olympians from nine nations who had competed at Rio 2016 successfully made the switch from sevens to fifteens by being selected for their national teams for the Japan 2019 tournament, including three players for the Japan team. One Fijian player commented (RWC 2019a): “there are challenges going from sevens to fifteens, you don’t have as much space so it’s hard to get through the forward line, but it does give you pace, flexibility and agility.”

The Blossoms style of play has been described as free-flowing, electric, inventive, fast-paced and compensating for their smaller physicality, reminiscent of media comments made about the Witches back in the 1960s (RWC 2019b; Guardian 2019b). The style played by the Japanese and the success of the Brave Blossoms in 2019 could potentially lend itself to players switching more comfortably between the fifteens and sevens game, with star players like Fukuoka Kenki firmly in the running for selection in the Tokyo 2020 team, having already competed at Rio 2016, and with two Rugby World Cups (2015 and 2019) under his belt.

Women’s rugby is one of the fastest growing sports in the world, and the inclusion of both the women’s and the men’s game in the Olympics from 2016 is both a reflection of the rise of the women’s game (as the Olympic Charter rules state that for a sport to be accepted into the Olympics it must meet participation rules for both men and women) as well as a potential driver to increase its popularity. While the focus has been on the men’s game in 2019, in that year the Guinness company ran a marketing campaign unveiling the inspirational story of a Japanese women’s team that defied social conventions back in the 1980s, and two Japanese players were picked for the Women’s Barbarian squad, which in 2017 launched a women’s team for the first time in the invitation club’s history dating back to 1890. Japan’s national women’s rugby union team currently ranks 12th in the world rankings and, like their male counterparts, are the strongest Asian team (World Rugby 2020). Japan’s women’s rugby teams, nicknamed the Sakura Fifteens and Sakura Sevens, have some way to go before they match the popularity of the Japan women’s Nadeshiko national football team, but the game is steadily growing. The Japan women’s team qualified for Rio 2016, coming 10th (out of 12 teams) in the first Olympics for rugby sevens and, as hosts of Tokyo 2020, Japan’s men and women’s rugby sevens teams both automatically qualify.

From the Rugby World Cup 2019 to the Tokyo 2020 Olympics

Japan’s hosting of the Rugby World Cup in 2019 not only highlighted the rising sons of Japanese rugby, as the Brave Blossoms captivated domestic and international audiences with their flair and determination, but it spoke to World Rugby’s attempt to grow the game globally outside of the traditional north-south rugby playing nations, while bringing the sport of rugby into the hearts of the Japanese people. The Top League games in the Japanese rugby calendar for 2020 are already reporting record attendance figures. The Rugby World Cup cemented Japan’s ability to not only successfully host a mega-sporting event, but to showcase the spirit of gambaru – a single verb that contains notions of perseverance, tenacity, toughing it out and a determination to do one’s absolute best. It is a term that has been commonly used when Japan has had to rebuild after devastating natural disasters to which the country is geographically prone, such as the 1995 Kobe earthquake and the 2011 Tōhoku triple disaster (Creighton 2015). The imperative form gambare! is also used by fans at sporting events to shout out encouragement for athletes and teams. The spirit of gambaru was core in Japan’s hosting of the Rugby World Cup particularly for the city of Kamaishi, that had harnessed its iron & steel based rugby heritage as a means to focus its recovery from the 2011 tsunami and gain selection as a rugby host city. When a super typhoon devastatingly hit in the middle of the competition, threatening the tournament and resulting in cancellation of two games, including one in Kamaishi, the spirit of gambaru was put to the test. Japanese organizers slept in the Yokohama stadium overnight as the typhoon hit while hundreds of volunteers arrived the next morning to clear water and debris ensuring Japan’s historic game against Scotland could take place that day. The spirit of the Japanese to get behind competing national teams, cope with a national emergency in the midst of the competition, as well as flavor the mega-event with Japanese style omotenashi hospitality captured the attention of foreign fans who had travelled to Japan, as well as audiences following the tournament around the world. The organizers of Tokyo 2020 will no doubt be keen to learn from and build upon this experience, and tap into the momentum of sporting enthusiasm it has generated. At the same time they are conscious of the desire to stage a second Summer Olympics and Paralympics that recaptures the imagination of the significant cohort of Japanese who remember the magic of 1964 in their youth, while also speaking to a new generation. The desire is there to once again use the staging of the Olympics in 2020 to showcase Japanese technology, creativity, culture and hospitality, but to also push a growing agenda and necessity for greater acceptance of diversity in Japanese society through the power of sport.

References

Creighton, Millie, 2015. ‘Wasuren! We Won’t Forget! The Work of Remembering and Commemorating Japan’s and Tohoku’s (3.11) Triple Disasters in Local Cities and Communities’, Journal of Global Initiatives: Policy, Pedagogy, Perspective 9(1:8).

Daimatsu, Hirobumi, 1963. Ore ni tsuite koi. Tōkyō: Kōdansha

Fukuda, Takuya, 2010. ‘Kigyō Supōtsu ni okeru Unei Ronri no Henka ni kansuru Shiteki Kōsatsu – Nihonteki keiei, amachua, masumedia no hattatsu o bunseki shiza toshite’. Ritsumeikan Keieigaku, 49(1).

Galbraith, Mike, 2016. Rugby established in age of Shoguns & Samurai. Galbraith Press.

The Guardian 2019a. Brave Blossoms challenging old ideas of what it means to be Japanese. 9 October 2019.

The Guardian 2019b. Japan ready to hit Samoa with fresh array of trickery and invention.

Kasai, Masae, 1992. Okāsan no Kinmedaru. Tokyo: Gakken.

Kietlinski, Robin, 2011. Japanese Women and Sport: Beyond Baseball and Sumo. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Macnaughtan, Helen, 2012. ‘An interview with Kasai Masae, captain of the Japanese women’s volleyball team at the 1964 Tokyo Olympics’, Japan Forum 24(4): 491–500.

Macnaughtan, Helen, 2014. ‘The Oriental Witches: Women, Volleyball and the 1964 Tokyo Olympics’, Sport in History 34(1) 134-156.

Macnaughtan, Helen, 2019. ‘Can sporting mega-events bring change to Japan?’, East Asia Forum.

Merklejn, Iwona, 2013. ‘Remembering the Oriental Witches: Sports, Gender and Shōwa Nostalgia in the NHK Narratives of the Tokyo Olympics’. Social Science Japan Journal 16(2).

RWC 2019a. Olympians set to make Rugby World Cup history at Japan 2019.

RWC 2019b. Brave Blossoms proving to be a lot more than just brave.

Sawano, Masahiko, 2008. Joshi Barēbōru no Eikō to Zasetsu. Hokkai Gakuen University.

Takaoka, Haruko, 2008. ‘Katei Fujin Supōtsu Katsudō ni okeru ‘Shufusei’ no Saiseisan: barēbōru no hatten katei to seido tokusei o chūshin ni’. Research of Physical Education 53(2) 391–407, Japanese Society of Physical Education, Health and Sport Sciences.

Tomizawa, Roy, 2019. ‘Japan Falls in Love with the Brave Blossoms: Shades of the Women’s Volleyball Team at the 1964 Tokyo Olympics’, The Olympians: from 1964 to 2020.

World Rugby 2020. World Rugby Women’s Rankings (January 2020).