Abstract: This short essay is a personal reflection by a socio-cultural/medical anthropologist of Japan with a long-standing research interest in hikikomori (social withdrawal). I re-examine the notions and the roles of so-called “experts.” Then, I will situate the “new normal” under the pandemic in relation to definitions of hikikomori. I conclude by sharing my hopes for a renewed sense of sociality in and beyond the pandemic age.

Towards a Renewed Sense of Sociality in the Pandemic Age

It’s July 6th in Tokyo, and I have not taken any public transport, or met any friends face-to-face for almost four months now. I have gotten somewhat used to this routine, and am quite proud of myself for being a “good citizen,” properly assimilating into “the new lifestyle” (atarashii seikatsu-yōshiki) promoted in early May by the “Expert Meeting” (Semonka-kaigi), an advisory body established in the New Coronavirus Infectious Diseases Control Headquarters of the Japanese Cabinet. My old friends jokingly told me, “The hikikomori expert has now become hikikomori!”

I guess I am an “expert” of sorts on the hikikomori (youth social withdrawal) issue in Japan. I have conducted anthropological research on this topic for my doctorate and have published on this theme over the years (Horiguchi 2011, 2012, 2017). I have done several interviews with Anglophone media on this topic and have also been asked to advise on what to do with specific hikikomori cases as an “expert”. But there has always been a slight sense of discomfort with being addressed “Horiguchi-sensei: the “hikikomori expert.” I have researched hikikomori for many years, indeed, but does that make me an “expert”?

Perhaps, the awkwardness comes from how in my discipline of anthropology, there is this sense that researchers learn from everyone we meet in the course of our long-term fieldwork, and the real “experts” are them, not us. You can never do good fieldwork unless you get the locals to correct the mistakes you make in the field. Most anthropologists would probably be happy saying that they specialize in (senmon to suru) the areas they have worked on but would feel awkward to be called “experts” (senmonka). A few years ago, when a team of anthropologists including me were invited to give a medical anthropology workshop to doctors in primary care and were introduced as “the experts of medical anthropology,” we all seem to have felt a bit weird. Despite being aware of how tight we were with time, each of us ended up making rather long excuses in our self-introductions about how we were not really “experts” as such. We truly appreciated the respect we received from the doctors who would be called “sensei” on a daily basis in their own work, and we believe we anthropologists responded with professionalism, but I was not the only one cringing about being treated as an “expert” by the well-respected sensei doctors.

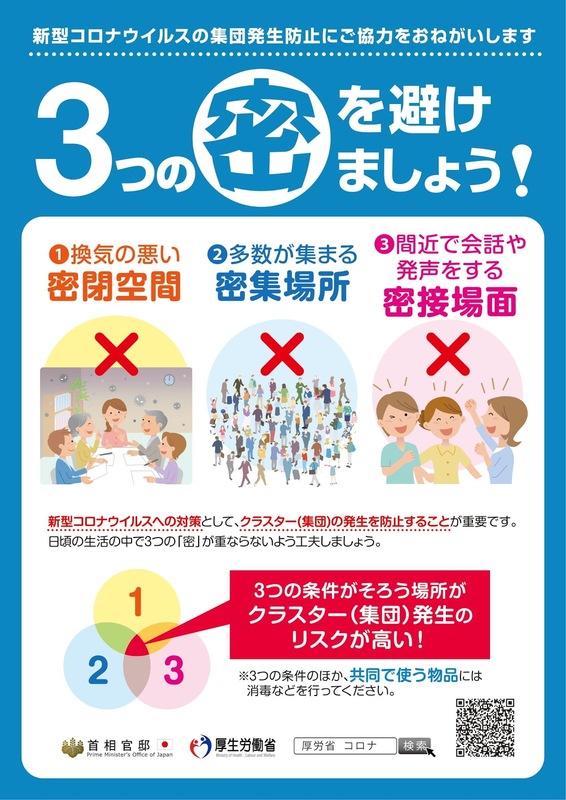

This brings me to the question of who the so-called “experts” are, when we are dealing with the novel coronavirus: COVID-19. In Japan, the Expert Meeting was launched in February, including “experts” in infectious diseases, public health, virology, and law (Cabinet Office 2020), and this team, along with the COVID-19 response team under the MHLW (Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare) has led COVID-19 responses, from informing the public of the importance of avoiding “3-mitsu” (3-intimacies, or the three C’s: closed spaces, crowded places, and close-contact settings), to analyzing data collected from health centers and tracing and intervening in “clusters” of infected cases.

Japanese government’s poster alerting citizens to avoid 3-mistsu

(closed spaces, crowded places, and close-contact settings)

The roles and the positionalities of the Expert Meeting remained ambiguous, however, and in fact, an unofficial member emerged as a prominent face of the team: Nishiura Hiroshi, epidemiologist, famously dubbed “80% Oji-san” (Mr. 80%) for urging the public to cut down on person-to-person contact by 80% (Nishiura 2020). Considering that COVID-19 emerged as a novel, unknown virus, researchers all over have been working on figuring out the nature of COVID-19, and there is probably no real expert at this point on COVID-19. Nevertheless, it seems that the Japanese “experts” have established their positions as such, and with so much impact they have on wider society, they cannot shy away from being deemed “experts”.

While the death toll in Japan has remained relatively low, amidst criticisms made by other so-called “experts” in media against the Expert Meeting and concerns raised from its members about its positionality, economic revitalization minister Nishimura Yasutoshi announced abruptly on June 24th that the Expert Meeting is to be disbanded, with a new sub-committee placed under the government’s COVID-19 advisory council board from July (Sugiyama 2020).

Since March, I have been joining a collaborative interview project on COVID-19 responses of primary care professionals in Japan―which builds on the collaborations between anthropologists and doctors in the aforementioned workshop―but I am clearly not an “expert” on COVID-19 and would not join the ranks of so-called “experts” from various fields who have attempted to criticize the Expert Meeting in both mass and social media. I do not have the expertise to evaluate the contributions of the Expert Group or the credibility of its members.

But in terms of hikikomori, have I become more of an “expert” through keeping up a rather hikikomori-like lifestyle in the “new normal”? There are varying definitions of hikikomori, but most would note that if you have not “socially participated” (shakai-sanka) and if your life has been centered around your home for over six months, you would qualify as a hikikomori. Since I have not met any friends face-to-face for almost four months now, if I continue on like this for another two months, would I then officially become hikikomori and possibly enhance my positionality as an “expert” due to the virtue of being hikikomori myself?

Not really. For one thing, it is worth noting that “experts” imply those situated at the opposite end of the spectrum from the ones directly affected by an issue, called tōjisha in Japan. “Experts” are often seen as those who can solve the problem and carry more voice in public discussions of issues than the tōjisha. The tōjisha are often empowered by such discourses and practices the “experts” bring to society. But they are often positioned as objects of problem-solving, and may also be exploited or muted by the “experts”―in cases where the “experts” abuse tōjisha voices to gain credibility or present their own arguments as “objective analyses” superior to the tōjisha’s “subjective” perspectives. Another specific aspect about hikikomori is that lack of “social participation” for hikikomori is not only about the lack of face-to-face sociality, but also about not being a productive worker and/or attending school/college as a student. I have been working hard over the last few months, preparing and doing online classes from home, and have been receiving my salary. My case does not neatly fit into the definition of hikikomori. As Takahashi (2020) wrote, there is a big difference between temporarily being hikikomori while working remotely and being hikikomori without your own source of income. Academics (and white-collar workers) like me have the luxury of enjoying a stable income while being at home under COVID-19, and I am concerned with the ever-widening inequalities that the pandemic has made visible.

Nevertheless, based on what I have learned from both the “experts” and tojisha of hikikomori, I have always hoped for a society where hikikomori is not stigmatized. My hopes are for a “new normal” under the pandemic and beyond, with more expansive opportunities for people to engage in “social participation” without being forced into the messy and complex realities of face-to-face sociality. Japanese workplaces have been notorious for valuing face time at the workplace over productivity, but hopefully under COVID-19, more employers will consider recruiting workers who can be more productive if they are not bothered with having to join in small talk with their colleagues, and/or adopting innovative technologies like OriHime which has helped those with disabilities to work remotely using avatars (Tomura 2020). Japanese education has been known to emphasize “social learning” cultivated through spending much time with peers in the physical setting of the school and has been reluctant to accommodate home schooling. Under COVID-19, we may have often heard of children missing their friends from school. But my research has highlighted the existence of children who feel safer if they do not have to be faced with bullies or to perform their persona to get along with peers at school. I hope that accessibility to online learning will improve for children of all backgrounds, allowing them to be fully granted the rights to learn wherever they are. The pandemic has posed us with uncertainties and widening divisions in society that “experts” and non-experts have been struggling to grapple with, but I hope it has also prompted us to redefine sociality for creating a more inclusive society.

References

Cabinet Office (2020) Shingata Coronavirus Kansenshō-taisaku Senmonka-kaigi no Kaisai ni-tsuite [On holding the expert meeting for measures against COVID-19]. (accessed July 6th, 2020)

Horiguchi, Sachiko (2011) “Coping with Hikikomori: Socially Withdrawn Youth and the Japanese Family” in Richard Ronald and Allison Alexy (eds) Home and Family in Japan: Continuity and Transformation. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 216-235.

Horiguchi, Sachiko (2012) “HIKIKOMORI: How Private Isolation Caught the Public Eye” in Roger Goodman, Yuki Imoto, and Tuukka Toivonen (eds) A Sociology of Japanese Youth: From Returnees to NEETs. London and New York: Routledge, pp.122-138.

Horiguchi, Sachiko (2017) “’Unhappy” and Isolated Youth in the Midst of Social Change: Representations and Subjective Experiences of Hikikomori in Contemporary Japan” in Barbara Holthus and Wolfram Manzenreiter (eds) Life Course, Happiness and Well Being in Japan. London and New York: Routledge, pp.57-71.

Nishiura, Hiroshi (2020) “[Tokubetsu-kikō] ‘8-wari Ojisan’ no Sūri-model to sono Konkyo: Nishiura Hiroshi, Hoku-dai Kyōju” [Special column: “Mr. 80% explains the Numbers behind Coronavirus Modelin] Newsweek Japan: June 11th, 2020. (accessed July 6th, 2020)

Takahashi, Tadasu (2020) “The trouble with linking COVID-19 to ‘hikikomori’” The Japan Times: May 15th, 2020. (accessed July 6th, 2020)

Tomura, Keiko (2020) “Robots expand the world of the disabled” NHK World: December 19th, 2018. (accessed July 11th, 2020)