Abstract

This paper examines exhibits at the Shanghai Expo and the urban improvement schemes undertaken for the Shanghai Expo for what they reveal about the ideals for and experiences of urban modernity in contemporary China. Rather than focus on the experiences and perceptions of a global audience, this paper examines how the Expo sought to speak to a domestic audience about state legitimacy through its messaging about urban citizenship and urban modernity. It argues that the manner in which the Expo promoted certain forms of sustainability and the domestic audience’s experiences with Shanghai urban improvements revealed tensions in the nation’s development model and excluded sectors of the population from participation.

Keywords: Shanghai Expo, urbanization, sustainability, China

Introduction

In the period leading up to the 2010 Shanghai Expo, Chinese media outlets and historians drew attention to a work of science fiction published a century earlier. The 1910 novel, by the noted physician Lu Shi’e, was prophetically titled New China. Set in Shanghai, its protagonist awakes from deep slumber to discover a phantasmagoric city of underground transportation tunnels, electric lights, and elevated bridges across the Huangpu River that bifurcates the city. In the novel, these futuristic modes of passage linked Shanghai proper to the sleepy agricultural district of Pudong, which was hosting a glorious, universal exhibition. Exactly one hundred years later, Pudong had become not only the core of contemporary Shanghai’s financial and commercial activity but also the site of the 2010 Shanghai Expo, a universal exhibition—like that imagined in New China—that presented its host city as the epitome of global urbanity: Lu Shi’e’s science fiction had become Shanghai reality. As Shiloh Krupar has noted, “conjoin[ing] Shanghai’s renaissance to the revival of the contemporary world Expo format” thus appeared to fulfill “Shanghai’s destiny as a global city” (2016: 2; see also Winter 2012).

|

Typical lines for the China Pavilion (photo by author) |

The Shanghai Expo was the biggest in history (covering 5.3 square kilometers) and the most expensive ($45-50 billion); it also received the most visitors (73 million) and welcomed the largest number of nations and organizations (246). These record-breaking figures and the global ambitions of the Expo led many Western commentators to read the fair predominantly as a promotional effort intended to increase China’s international stature and provide a counternarrative to western discourses that encoded China’s rise to global power as a threat to the international order.1 Before the Expo was even over however, many of these same commentators had declared China’s grand efforts an equally grand failure; few non-Chinese attended or found the event significant, they explained, and those who attended failed to mention a decline in their fears and criticisms of China. This essay has two responses to that argument, one methodological and one conceptual. First, it maintains that such assessments of the Expo as a failed attempt to influence global opinion miss a more important point about the mega-event’s diverse goals and audiences. While the Expo clearly expended great effort to display China’s growing power to a global audience, and indeed, its global economic power played a role in why the nation was awarded the event (Sze 2015: 133),2 the domestic audience was arguably of equal importance (see also Aukia 2014; Ding 2012; Wang 2013). That is, the Expo’s goals included not only assuaging global trepidations about China’s growing global stature and convincing global citizens that China’s rise to power is a legitimate and peaceful one, but also persuading Chinese residents of the achievements of the state’s modernization efforts, despite their sometimes dislocating and ambiguous effects. Thus rather than focus on the experiences and perceptions of a global audience, this paper examines how the Expo sought to speak to a domestic audience about state legitimacy.

The most pragmatic empirical impetus for thinking through the Expo from the perspective of a domestic audience is that 95% of the visitors were Chinese citizens and that this was expected well before the event opened (Mullich 2010; Peng 2010).3 While the displays from other nations and international organizations included extensive English and foreign language signage and bi/multi-lingual tour guides who provided information and context, this was not typically the case with the Chinese government and Chinese corporate-sponsored pavilions and events. Consequently, many of the specific messages communicated by the Chinese-sponsored pavilions may have been opaque to most non-Chinese visitors. From a routine lack of foreign language commentary at the Chinese-sponsored displays, movies, and performances to frequent references to arcane cultural traditions and unique political histories, visitors who neither spoke Chinese nor had training in China studies would have had difficulty comprehending the symbolism and meaning of the representations. Few would have understood, for instance, that the “boat ride” through the China pavilion featured reproduction rocks from Lake Tai, also known as “spirit stones,” that were built into scenes representing whimsical utopias. Neither would they have understood the accompanying Chinese-language commentary that embedded the narrative within a cautionary tale about the environment through a wistful reference to guizhen fanpu, a phrase that translates literally as a return to nature or innocence that in this context referred to the contemporary devastation of the world’s ecological systems.4 And few foreign-language guides were available to explain these references, thus leaving most non-Chinese visitors to appreciate the spectacle as a largely impressionistic visual experience. Local residents and Chinese visitors with whom I spoke frequently affirmed my impression of the centrality of the domestic audience for the Expo’s organizers, such as the college senior from Shanghai who commented, “I think it’s great, but foreigners can’t understand it. It’s only for Chinese people to enjoy” (see also Winter 2012). Following such claims that a domestic audience might “enjoy” the event more, this paper focuses on Chinese-sponsored displays that were arguably directed specifically toward a domestic audience who were intended to absorb the Expo’s message about China’s modernity.

Where this essay’s first argument concerns who might have been a target audience at certain Expo exhibits, the second concerns specifically how the Expo addressed this domestic audience, how it defined this modernity. Contemporary modernity is typically described as an urban phenomenon (Roy and Ong 2011; Sassen 2005; Zukin 1992) and Shanghai’s expo was the first dedicated to highlighting a specifically urban modernity.5 China’s urbanization has been rapid and massive. From representing only 13% of the population at the time of the 1949 revolution, urban citizens in 2018 constitute nearly 60% of the population.6 Not including Hong Kong, mainland China has 123 cities with over one million inhabitants (United Nations 2018), and the state’s goal is an urbanization rate of 70% within the next decade (Johnson 2013a).7

The official theme of the Expo, which in English was “Better City, Better Life,” made explicit the event’s intentions: to showcase, as the promotional materials explained, “the full potential of urban life” and to “disseminate advanced notions on cities and explore new approaches to human habitat, lifestyle and working conditions in the new century” (“Brief Introduction” 2008). Yet tying modernization and modernity to urbanization has occasioned not only the spectacular architecture and massive subway systems for which China has become renowned, but also a host of problems and inconveniences, including the disenfranchisement of rural farmers forced to cede their lands and livelihoods, and the environmental degradation, smog-choked towns, infrastructural overload, and congested roadways that accompany China’s position as the world’s largest emitters of greenhouse gases (Economy 2004; Kahn and Yardley 2007; Tilt 2009).

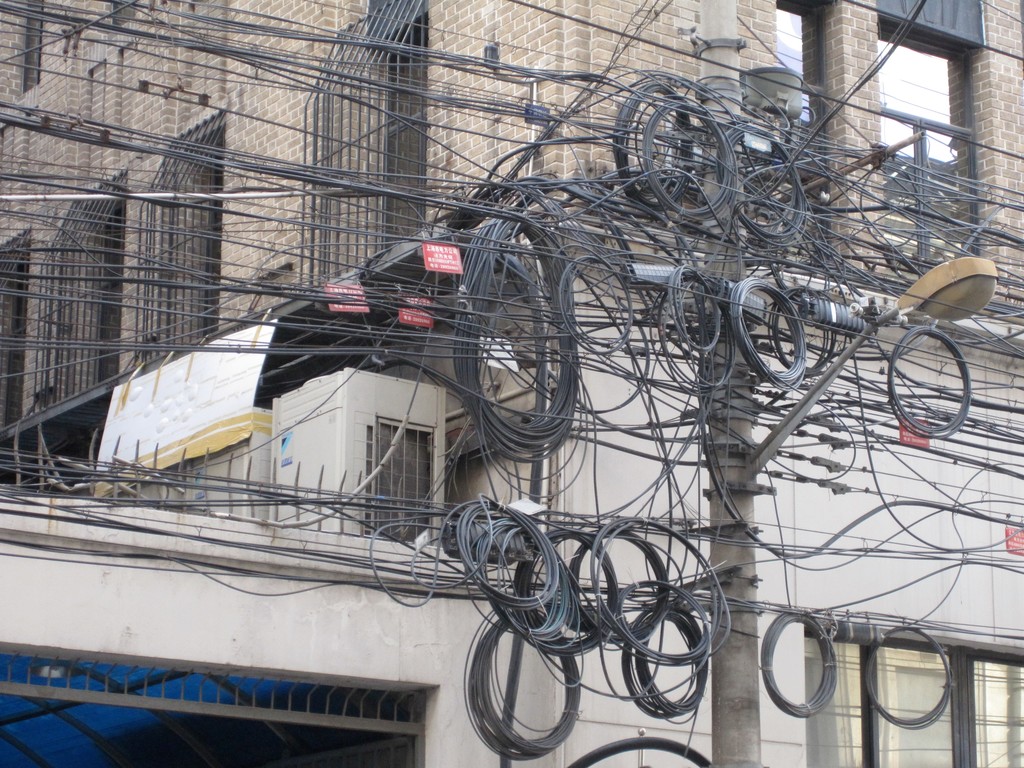

|

Infrastructural overload in Shanghai (photo by author) |

The Better City, Better Life theme suggested, perhaps unintentionally, these hazards of urban modernity. While the English version intimates that improving cities will enhance urban life—i.e., that making cities better will make citizens’ lives better—a literal translation of the Chinese version more explicitly expresses the state’s massive urbanization-centric development model: “Cities Make Life Better.” This translation implies that urbanization itself improves lives, not the specific nature of the urban spaces (see also Callahan 2012; Connery 2011; McAuliffe 2013) it also ignores the problems wrought by China’s rapid urbanization process or the tensions and inconsistencies within the vision itself. In other words, the Chinese version of the theme insinuates that urban spaces improve lives, with no regard to the quality of those urban spaces or aspiration for improvement. Indeed, many of the Chinese visitors to the Expo and Shanghai citizens I interviewed commented that, in fact, cities do not necessarily improve life and that the English version better represented the reality of urban living. As one visitor explained to me, “It makes sense in English. I suspect that the English came first and then they translated it into Chinese. But the Chinese doesn’t make sense, because really in cities, there is all this traffic, pollution. It doesn’t make life better at all.” At the same time, this paper argues, the better cities mantra ignores the increasingly exclusionary nature both of Chinese cities and the Expo’s ideals of urban citizenship. Cities make life better for whom? While the Expo both explicitly promoted the state’s developmental schemes and extended potential solutions for some of the pitfalls of global urbanization, this essay argues that it did so in a manner that also excluded certain segments of the population from participation in urban life. It would have revealed to a domestic audience with direct experience in China’s cities the fundamental and stark tensions in the nation’s urban developmental model and the fact that urban citizens interviewed for this essay were located in a strategic position to evaluate the state’s efforts to promote its urban modernization and development schemes.8

|

Expo rendering of tribulations of urban experience (photo by author) |

This article, based on ethnographic observations and data gathered among Chinese visitors to the Expo and Shanghai residents, thus seeks to illuminate the lessons that the Expo and the related infrastructural and aesthetic improvements in Shanghai were intended to project to a domestic audience. Specifically, it examines both the utopian interior spaces of the Shanghai Eco-house display (Shanghai at Expo) and the new-and-improved exterior urban spaces (Shanghai for the Expo) in which the event was staged. As such, it seeks to reveal both the ideals for urban space as constructed at the Expo and the tensions that emerged through practices of urban modernity in the space of the city itself, to illuminate how the state employs the urban to animate its political legitimacy and the conflicting implications of the representations and the process itself.9

Urban Modernity at the Expo: The Shanghai Eco-House

|

Entrance to the Shanghai Eco-house (photo by author) |

The Shanghai Eco-house, promoted as a model for modern family living, was a four-story detached dwelling built from materials recycled from a green office building formerly located near Shanghai’s city center and featuring energy-efficient technology. It was one of the most prominent of the prototypes in the Urban Best Practices Area (UBPA) of the Expo. This area featured eighty case studies from around the world, in both conceptual and built format and was the most comprehensive and concentrated version of the event’s vision for contemporary urbanism.10 The UBPA, located on the west side of the Huangpu river, far from the immense crowds on the east side of the river where the national pavilions were located, offered visitors a relatively tranquil space in which to meander between displays, saunter down intersecting pathways and over bridges, and contemplate a broad range of practices designed to enhance urban living. Much of the UBPA was geared toward discussions of environmental sustainability and the Eco-house offered an exemplary model.

Nonetheless, although the building’s “eco” prefix suggested an environmentally aware form of sustainability, its interior pedagogies offered a more expansive interpretation of the concept and this section explores the diverse and often conflicting concepts of sustainability that the Eco-house promoted as ideal-type forms of urban living. First, it details the exhibit’s straightforward promotion of environmentally sustainable urban living; second it investigates how the specific paradigm of environmental sustainability also promoted an “economic” sustainability that exacerbates global ecological conditions; and third it analyzes what I call a “social” sustainability that projected Chinese tradition as a model for built and conceptual urban futures.

The most prominent form of sustainability promoted in the Eco-house was environmental sustainability. Immediately as I entered the building, I noted the smell of a greenhouse and encountered a hydroponic “living” wall of greenery intended to improve air quality and provide health benefits. The semi-subterranean placement of the first-floor courtyard and atrium provided natural lighting, and the live roof absorbed rainwater and insulated the dwelling. Designers had incorporated an energy-saving building system that utilized inorganic thermal insulation coated with heat-reflecting paint and constructed interior walls with flue gas gypsum board that releases less sulfur dioxide than traditional drywall. Energy was generated and water was heated by solar and wind power; rain and waste water were recovered; the façade incorporated recycled bricks from demolished local traditional-style housing; and the concrete entryway steps contained reprocessed materials. The interior of the Eco-house offered a similar tour through the advances and offerings of green enterprise. The building integrated a window dressing system that adjusted the direction of blinds automatically according to the position of the sun, low-energy lighting, low-flow toilets and showerheads, a fuel-cell home-energy center, and the “living wall” that stored energy and regulated the temperature and humidity in the room. The house tour ended with a passage through the “New Energy Garden” that further elucidated the energy-saving features of the prototype and urged green consumption upon visitors.

This concept of sustainability was clearly intended to address the problems of a global modernity that has wrought devastation on the wellbeing of both the natural environment and the earth’s citizens, especially in China, where, for example, in 2015, pollution was linked to 1.8 million deaths (Sifferlin 2017). In addition, it reflected China’s policy commitments to renewable energy and desire to lead global environmental accords. But even as the Eco-house explicitly defined sustainability in relation to the environment, it implicitly but just as insistently characterized it in terms of economic growth in a manner that both reinforced the state’s consumer-driven urbanization schemes and posed a major obstacle to environmental concerns.11 Although the explanatory panel at the entrance to the Eco-house’s water recycling center noted that it was “more important to sustain our beautiful world than to succeed in business,” I argue that a second form of sustainability presented in the dwelling, what I call “economic sustainability”, made clear that great financial success would have been required to inhabit it.

The Eco-house promoted economic sustainability through its omnipresent product placement and brand marketing that suggested visitors purchase their way to ecological progress through buying green products and brand name appliances. The highly modern bathroom area that incorporated a gray water collection system, for example, also featured elegant shallow Kohler sinks embedded in a granite countertop and others attached in random fashion to the wall in a manner that resembled an upscale showroom for lavatory products and walls decorated with photos of infants labeled “Kohler babies.”

|

Kohler display (photo by author) |

In a similar vein, electronics and furnishings throughout the building prominently sported prominent globally recognizable trademarks. One parlor included a Philips-brand leather armchair that recorded vital statistics and displayed the corresponding information on an adjacent screen, while another featured several uncomfortable looking, geometrically shaped cushions situated obliquely on the floor near a large, flat-screen Phillips television. A starkly white adjacent kitchen reinforced this consumer model of modernity with more branded screens, one that allowed home chefs to view recipes and order groceries online.

|

Eco-house kitchen (photo by author) |

When I exited the building after my first visit, I felt as if I had just emerged from the hybridization of a corporate product fair and an environmentally friendly IKEA, offering room after room of product displays, kitchen fittings, and green technology.12 While the Eco-house’s version of modern urban citizenship emphatically entailed a commitment to sustainability, one would clearly need to purchase the way there.13 This showcasing of “green consumption” is not unique to China by any means, but is representative of a form of what some have called a “bourgeois environmentalism” (Mawdsley 2009: 249) that requires economic resources far beyond the means of a large swath of the Chinese population: the approximately 600 million people in China who lack access to indoor plumbing and the citizens in Shanghai living on a minimum monthly wage of less than $400 per month would have been excluded from participating in this consumer-driven form of modern urban citizenship.

The third form of sustainability on display at the Eco-house was the most subtle and the most specific to the cultural experiences of a domestic audience. Here, the Eco-house took a sharp detour from the “eco” part of its sustainability message to promote a “social sustainability” that projected Chinese tradition as a model for built and philosophical urban futures. The Eco-house, rather than locating tradition as antithetical to urban modernity, instead wed it to Chinese cultural history and economic growth to offer tradition as a prescription for addressing modernity’s putative hazards. In this, it reflects President Xi Jinping’s proclamation that traditional Chinese culture offers “a foundation for China to compete in the world” (China Daily 2014).

This elaboration on tradition to define modern urban citizenship took multiple forms at the Expo—in construction strategies derived from fengshui standards and centrally located traditional art work and furniture, to mention just a couple. Its most persistent expression at the Eco-house was through continuous reference to the three-generation family, as in Chinese-language labels that read “Three-generation Living Room” or “Three-generation Kitchen,” whose meaning was lost in English-language signage that described these spaces as “Living Room for All” and “Future Kitchen.”

The three-generation family unit featured in the Eco-house included grandparents, parents, and children, with the parent/child unit described as a “three-person family” (“cozy core family” in English) and incorporated the presumed varied living styles, quotidian needs, and cultural habits of each of the generations. Reflecting these different age groups, the first floor was labeled the “youth apartment” and included a “reading room” that featured a wall of various forms of reading material behind plexiglass (from parchment scrolls to books) and a pillowed nook area set against a backdrop of dozens of e-readers hung on the wall, presumably for the technologically savvy younger generation. Designers devoted another level of the house explicitly to the grandparent generation with rooms labeled “elderly kitchen,” “elderly parlor,” “elderly toilet,” “elderly bedroom,” and “elderly lounge.” One of these rooms associated age with tradition through a full-wall, classic-style painting of pagodas set in a lush landscape that depicted historical Shanghai. The bedroom and lounge similarly juxtaposed new and old with Philips flat-screen televisions situated over intricately carved wooden daybeds and laptops resting on traditional desks.

|

Generation-appropriate reading material (photo by author) |

Even though changing cultural predilections and economic practices have rendered such living arrangements increasingly rare in contemporary China, having multiple generations residing under “one roof” has long constituted an ideal for Chinese family life, symbolizing such philosophical values as harmony and longevity but also reflecting socioeconomic conditions in which labor and resources are pooled among siblings to support elders and children.14 Historically, extended families dominated Chinese society, both demographically and philosophically, providing practical benefits in terms of both child and elder care and economies of scale. Similarly, the Eco-house’s promotion of multi-generation cohabitation encourages several positive outcomes from the perspective of the state and its desire for social stability that could be read as an attempted antidote for the ills of state policy that have included declining rates of fertility and an inaccessible housing market. The extended family living arrangement has the potential to help stabilize an overheated and exclusionary housing market by reducing pressure on availability; in the face of reduced fertility that has led to an impending labor shortage and aging population, it enables built-in child care that might encourage increased child bearing;15 and it provides support for the elderly who remain insufficiently protected by a weak social security system for public sector retirees and a nearly nonexistent social security system for others. While the Eco-house spoke directly to a local population schooled in these traditions and facing policy-induced urban woes, it offered ideal-type narratives of family culture that belied contemporary experience where the nuclear family has emerged as a dominant norm and erected barriers to full citizenship. It assumed a monetary capacity to obtain a dwelling big enough for three generations, and more importantly, assumed the presence of three generations living in the same city space, something patently unavailable to migrant workers who constitute approximately 40% of the urban population and frequently are forced to leave children with grandparents in the countryside because of urban policies that deny them education and health care.16

While the Eco-house prototype presented urbanization as making life better, the particular forms of urban life that it acclaimed—environmental, economic, and social sustainability—also revealed tensions in the state’s construction of the urban modern. The goals of the exhibit often seemed at cross purposes, not only because of the inherent frictions between consumption and environmental sustainability promoted in Eco-house, but also because the model erected barriers to full citizenship for those without the necessary economic resources or proper registration to participate. At the same time, whereas some of the exhibition’s messaging about sustainability—particularly the references to environmental and economic sustainability—would have resonated with global audiences, both the ideals for and tensions in these models for urban citizenship would have spoken purposefully to a domestic audience experienced in how the state’s official development policies offered normative models for urban citizenship that both motivated certain cultural ideals and practices of family life and excluded a broad swath of the Chinese population from participation.

Shanghai’s Urban Modernity for the Expo: Infrastructure and Aestheticization

While the Shanghai Expo grappled with the challenges of urban sustainability, variously defined, it was also a central catalyst for urban regeneration in the city itself (see also Winter 2012). Expos, like other such mega-events around the world, provide occasions for spectacular forms of urban renovation and extension through which cities discover “embryonic pieces” of urban life to come (Houdart 2012: 130). Following suit, Shanghai served as a laboratory for the Expo’s thematic endeavors. These “improvement schemes” (Li 2005; Scott 1998)—large-scale, state-sponsored interventions to improve human life—were attempts to validate and valorize the state’s urbanization development model, to corroborate that cities do indeed make life better, and, as Cameron Macauliffe argues (2013), to suggest the emancipatory power of the city as the site of modernity. While the Eco-house defined “better city” through narratives of sustainability, the tensions in that model also presaged the ways in which Shanghai citizens read and interpreted the improvement schemes’ definitions of better.

The city’s improvements largely revolved around the development of infrastructure, particularly for transportation and what I call the aestheticization of urban space—through which the state enacted its vision of urban modernity. While some have argued that such improvements can be repositories “of power spread progressively and unproblematically across national terrain, colonizing non-state spaces and their unruly inhabitants” (Li 2005: 384), this essay seeks to problematize that assumption through exploring how local citizens experienced the transformations that were implemented in city space for the Expo. Some of this problematization was reflected by an exhibition at a local gallery during the Expo by artist Chen Hangfeng, whose title was an obvious parody of the Shanghai Expo theme: “Bubble City, Bubble Life” and involved a bubble machine installed inside an expansive metal cage. Inside the cage, the bubbles wafted gracefully throughout the space, only to burst when they hit the wire mesh of the cage.17 According to Chen, his performance art was a comment on Shanghai’s mega-event: “I think the concept of Expo starts from utopia, utopian-style architecture, futuristic imagination. It’s kind of like a bubble…. After the Expo is gone, everything’s going to be gone, right?” (cited in Lim 2010).

During the regeneration process prior to the Expo, Shanghai underwent massive infrastructural development that entailed new icons and categories of mobility.18 Among other projects, Shanghai erected two new airport terminals and a landmark cruise ship terminal (800 meters long), constructed the most extensive subway system in the world (adding six new lines), widened and repaved countless miles of surface streets, and dug a three kilometer transportation tunnel under the Huangpu River. World’s fairs have often featured representations of and paeans to mobility (Fotsch 2001; Greenhalgh 1991; Heller 1999), and Shanghai was nothing if not a city going places.

In my interviews, the massive upheavals and inconveniences that resulted from Expo-inspired efforts to construct a global city on the move occasioned constant discussions about the potential value of these urban improvement schemes that spoke to the tensions in the state’s development model. These conversations provided a classic example of the ways in which state-led “improvement schemes are simultaneously destructive and productive of new forms of local knowledge and practice” (Li 2005: 391). While states have visions for how the built environment might portend certain forms of legitimacy and power, such improvements may also be contingent and contested. And my interviews revealed the unpredictability of how the governed may respond to actions and changes allegedly made to improve their lives as they touched upon the material exigencies of everyday life and assessed the governmental agencies spearheading the transformation.

The comments of Chen Huiliang, an Expo volunteer and graduating senior in engineering at Tongji University, mirrored those of many others with whom I spoke and encapsulated the complex relationship Shanghai residents and frequent visitors had with the modernization strategies implemented in their city. “There are a lot of problems in the city, such as traffic jams…and environmental pollution. We need to find a way to solve those problems to make the city better.” Referencing the Eco-house Expo arena, he continued:

The Urban Best Practices Area offers many solutions to solve contemporary urban problems…. I can’t really say, though, that Shanghai is becoming better. I think the concept comes first. The Expo may not bring Shanghai anything practical. I can say that it will have negative effects on Shanghai; for example, boats are prohibited on the Huangpu River and some roads are closed. This will affect the economy negatively…. For practical stuff, Shanghai has built over 200 kilometers of subway…. It is too early to say whether the Expo will make Shanghai a better place for people.

|

Heavy pollution in Shanghai during the Expo (photo by author) |

Huiliang’s commentary highlights both the benefits and the potential conflicts surrounding the development of a world-model metropolis for the Expo. While his assessment recognizes the Expo’s efforts to model best practices for urban living, it also reveals possibilities for disengagement from state improvement schemes and hence potentially from certainties about state legitimacy. The daily encounters that mediate the changes in urban space (200 kilometers of subway for example) are often material—the construction noise and dust that “have [the] negative effects” of which Huiliang speaks—but also conceptual, and thus, while they might suggest a certain kind of urban modernity, they also might not “bring Shanghai anything practical” or prove worth the disruption they entailed.

|

The greening of the city (photo by author) |

A second urban improvement scheme that was highlighted in many of my conversations with Shanghai citizens and Expo visitors was the aestheticization of the city. This process involved standard beautification schemes designed to render city spaces more pleasing to the eye—such as planting more greenery and picking up trash—but also removing citizens and spaces from sights that were deemed “inappropriate” to the kinds of exclusive urban modernity modeled by the Eco-house. While Expo infrastructural projects projected a city on the move through creating automobile-friendly freeways, efficient subway systems, and sustainable public transportation, the Expo also moved its citizens in other ways as a form of aestheticization, beginning with relocating 55,000 people who inhabited the decrepit neighborhoods designated for the mega-event to the distant suburbs. This process mirrored, in real rather than conceptual form, the ways in which the Eco-house rendered “inappropriate citizens” (migrants and the poor) invisible. At the Eco-house, urban modernity was only available to a certain class of citizens; in Shanghai itself, these “out-of-place” citizens were literally forced out of the city center to distant suburbs for the aesthetic benefit of the tourists and wealthy citizens who could afford the skyrocketing rents.

Nonetheless, as we discussed the built environment of the Expo, Zhou Biyu, a literature student from Shanghai University, commented positively on these forced removals, which she described as among “other practical benefits” of the Expo “that improve people’s lives,” similarly ignoring which kinds of citizens might benefit and at whose expense. For example, she continued, “The Expo site used to be shantytowns and factory areas. Now these places have all moved. That area will become a sub-center for Shanghai. It will help the economic development in Shanghai.” Her response reflected the perspective of most of those I interviewed during my research in Shanghai, a population whose knowledge of the displacement process—an experience that by most accounts is traumatic, sometimes dangerous, and often disempowering—was mediated through laudatory popular press coverage and government announcements. Biyu’s comments made no specific mention of the many thousands of inhabitants who were dislodged from the shantytowns and factory areas of the Expo space but instead revealed an appreciation for the cosmopolitan deindustrialization and aestheticization of space that has marked the neoliberalization of cities throughout the world (Duncan 2003; Low 2003).

Although others I interviewed in Shanghai specifically mentioned the displaced urban poor while sharing their perspectives on the changing nature of the city, their comments were quite different from the negative analysis and criticism that displacement practices in China have garnered in western media. Yi Chuhua, a middle-aged librarian, for example, proffered the case of a “friend” who lived in the Expo region and was relocated to the distant suburbs of the city. Chuhua insisted, despite my skepticism and most western media reports to the contrary,19 that this friend “received four apartments in exchange for the relocation and is now rich.” In this conversation and multiple others I had with her, Chuhua praised the government for its ability to “get things done” and its “concern for the people.” Having witnessed the political turmoil of the pre-reform era, in a narrative that replicated state messaging, Chuhua positively compared the contemporary government officials whose “hearts have opened up” to those of the Mao era who “looked down on people” and lauded both the new, aesthetically pleasing public spaces and the supposedly improved housing provided for displaced residents.

But while Chuha’s comments could be read as a positive referendum on the state, they also reflected transformations in urban living and sociality that even she found less sanguine. Her praise for this new urban modernity belied the nostalgia she also expressed for the very world whose government-led destruction she had celebrated only moments prior. After defining “rich,” within the context of her friend’s relocation, as the ostensible ownership of multiple apartments in high-rise buildings on the outskirts of town, Chuhua quickly shifted gears and began to reflect wistfully upon her life as a young parent living in one of Shanghai’s densely built traditional neighborhoods, many of which have since succumbed to the Expo wrecking ball. “Before,” Chuhua explained, “all our houses were close together and neighbors had really good human feelings. When my son came home from school, if I wasn’t there, the neighbors would feed and take care of him. Now all the doors and windows are locked. There are no common spaces any longer. There aren’t the same human feelings. It’s going away.” “Rich” here connoted a form of human relationship less available as wealth comes to be defined through capital accumulation and consumption. Chuhua’s words described a different form of displacement than those who were physically relocated to the outskirts of town for the sake of the Expo—a displacement of sociality rather than space. Thus even though she celebrated the urban improvement schemes, she simultaneously critiqued the diminution of social relations that accompanied the process. Here again we see the ways in which the state’s efforts to shape social relations through architectural endeavors (three-generation dwellings, single family housing, collective space) are not neutral, as Chuhua describes. Rather they actively shape the kinds of interactions that occur and which are then sanctioned by sustainability and upward mobility.

While some old neighborhoods were razed to accommodate the Expo and remove unsightly shantytowns, others were demolished to erect upscale residential apartments and fashionable shopping venues that, by global norms of modernity, improved the visual schema of the built environment. Those that remained standing were whitewashed or surrounded with opaque fencing decorated with Expo advertising and scenes of absent greenery.

|

Expo advertising hiding urban “unsightliness.” The caption reads “Bringing the world together at the Shanghai Expo” (photo by author) |

As such, these efforts concealed decrepitude from unsuspecting passersby and, in complicity with an aestheticization through exclusion, physically isolated those economically unable to participate in China’s consumer-driven modernization schemes. Such endeavors distanced the city from its history as a leading hub of manufacturing and heavy industry in favor of a high-tech and service-oriented economic model of development. Mirrored high rises dotted the landscape where belching smoke stacks once stood, “unsightly” neighborhoods were safely ensconced behind impenetrable barriers, and “unsightly” residents were relocated to the outskirts of town.

While Chuhua praised these developments, Zhou Lanying, a high school teacher born and raised in Shanghai, framed the aestheticization process as a matter of “face”:

We’re very concerned about face…. It’s like we go through the same process all the time. Once the government decides we are doing some big thing, then we tear it all down and build it all up again, constant construction, face-saving projects. The construction is all about the surface—plant flowers, refurbish the fronts of buildings, repaint, add new fake brick fronts to buildings, close factories. All the beautification is a face-saving project.

Others framed their concerns about face in terms of wastefulness: “I actually feel that they shouldn’t be just painting all these old buildings,” insisted one Shanghai resident; “It’s just on the surface, they should be using the money to really help improve conditions, not just the surface stuff. They are just wasting money.”20 Here we see the improvement schemes literally white-washing landscapes in the name of sustainability, even if that white-washing fails to actually produce transformation. Therefore, making things “modern” and creating a “sustainable urban” means making the city pretty on the outside with little effort to improve the quality of people’s lives (Better City, Better Lives). It is not only about waste, but also about how urban modernity uses aesthetic projects to erase the dirt of industrial/urban practices and the relations that have built that modernity. And in reflecting on the white-washing, and the underlying motives and actual results of the state improvement schemes, these Shanghai citizens demonstrated at least some skepticism as to whether they really improved life for city dwellers. They also belied improvement efforts—the greening of city space for example or the many rental bicycles that might help to ease congestion—that could be viewed as positive steps towards ameliorating some of the pitfalls of urbanization. What they reveal in the process are the tensions inherent in the Expo’s narrative about urban modernity. Messages about environmental sustainability conflicted with citizens’ desires for car ownership; messages about economic sustainability conflicted with class exclusions and the grittier realities of urban living; and messages about social sustainability conflicted with growing isolation and displacement.

In Conclusion: Mega-events, Urban Modernity, and State Legitimacy

World’s fairs have long been deployed as spectacles of modernity, extending extravagant discursive messaging about culture and politics that locate nations within global hierarchies of power. The 2010 Expo seemed guaranteed to provide an opportunity for Shanghai to offer the city as the manifestation of these ideals, fulfilling Lu Shi’e’s New China vision that located Shanghai at the apex of cosmopolitan urban modernity. To this end, the Expo offered a prototype for urban practice that addressed both the devastating environmental effects of urbanization and the state’s desire to sustain economic and social development through the growth of high-tech, middle-class consumption and Chinese traditional cultural practices, contending that China could do modernity differently (and, it inferred, better).

Judging China’s performance of its version of urban modernity, however, most Western commentators described the Expo’s apparent attempts to win the hearts and minds of global citizens as having resulted in “a limited return on [China’s] investment” (Nye 2012). Western media perceptions that the Expo failed to convince a global audience of China’s ability to fashion global modernity were largely based on two assumptions. First, that China’s differences from western norms made it an unappealing model of modernity, and second, that world’s fairs themselves were long past their golden age. While foreigners might find Chinese culture appealing and be impressed by China’s vast history and rapid economic growth, “Beijing faces serious constraints in translating these resources into desired foreign-policy outcomes” (Gill and Huang 2006: 17) because its domestic political ideologies and practices threaten its status and acceptance as a global leader in a neoliberal world based on a capitalist, democratic ideal. According to Pepe Escobar (2010), as long as China remains unwilling to launch “real political and cultural opening up—beyond showing off its economic might,” even “Expo theatrics” are insufficient for China to “seduce the world” into accepting it as a legitimate world power.

At the same time, elite western media described expos in general as appropriate playgrounds for insular, unaware “kids” (lesser developed nations), but not for worldly, cosmopolitan, developed “first world” adults. Such commentaries depicted Western citizens as wary cosmopolites not easily impressed or seduced, in contrast to a naïve Chinese citizenry that lacked critical discernment. The Economist, comparing Shanghai’s massive Expo to a theme park, explained that world’s fairs have become a “lacklustre” brand in the developed world (“Living the Dream” 2010). Similarly, former New York Times and Wall Street Journal columnist Virginia Postrel relegated China’s Expo aspirations to the dustbin: “Americans long ago consigned world’s fairs to the toy box of history…. World’s fairs are designed for people from homogeneous cultures who are still impressed by electricity and foreigners. In 2010, that means the Chinese” (Postrel 2010).21

Given these assumptions about difference, how does analyzing the urban spectacle at the Expo and for the Expo help us to understand the mega-event’s potential as a tool of persuasion? This essay has argued that examining the Expo’s tutorials about and experiences of the urban for a domestic audience reveals the event’s fuller intentions and thus some alternative measures by which it should be evaluated. Although the Expo was a global event constructed in the interests of convincing global audiences of the value of China’s aspirations for modernity, my goal has been to explore it also as a lesson in national aspiration: one meant to convince domestic citizens of the value of the particular state-directed manifestations of modernity featured at the Expo and of the ways in which one embodies them, thereby helping a domestic population envision what it means to be urban modern and become invested in the process. Examining the event from the perspective of a domestic audience attuned to both global standards of urban modernity but also strategically situated and especially implicated in the practices and outcomes of local policy helps us not only to recognize the diverse aims of the Expo but also has important implications for understanding the tension between the perceived value of China’s developmental urbanization model: what “better” might actually mean in terms of improvements to urban space and who benefits from them. Fundamentally, it illuminates not only how “emerging nations exercise their new power by assembling glass and steel towers to project particular visions of the world” (Ong 2011: 1),22 but also how a domestic audience understands both its own modernity and China’s domestic legitimacy through reflecting on visions and practices of the global urban. Such mega-events like the Expo provide the state with an opportunity to project a vision of what sustainability might look like and how citizens should aspire to the urban modern and fulfill various urbanization goals including broadening transportation networks, rebuilding urban centers, greening city space, and getting rid of marginal populations. If the domestic population appreciates such improvement schemes as in fact creating better cities, they also extend a mechanism for the formation of domestic community, loyalty to the state, and regime legitimacy for its core constituency.

The success of such projects is difficult to assess. As this paper has shown, while the Expo messaging about urban sustainability offered best practices models to manage the economic, social, and environmental pitfalls of China’s rapid urbanization, the manner in which these best practices were represented at the Expo and implemented throughout the spaces of Shanghai itself revealed fundamental tensions and contradictions in the models themselves. One could in fact argue that the growing repression in China in recent years offers a sign that the state feels increasingly threatened by a restive domestic population that recognizes these conflicts and exclusions and that it must redouble its efforts to convince its domestic population that it remains the legitimate guardian of the nation. Through such mega-events performed domestically and abroad, the state makes an argument for its ability to improve China’s global status, both in its material capabilities and through enhanced global recognition. Such endeavors thus play a dual role; by promoting culture on the global stage, they hope to both diminish fears of a rising China and address a domestic population that recognizes itself in these promotions and credits the state for its own new form of modernity. What they remain unable to guarantee, despite extensive effort, is global or domestic agreement with their attempts to control those perceptions for the state’s efforts to communicate the surety of improvement through urban life is neither guaranteed nor attainable for those who cannot buy into its particular consumerist, middle-class version of it. Citizens are thus left questioning: Do better cities make better lives and who defines what better actually means?

Bibliography

Aukia, Jukka. 2014. “The Cultural Soft Power of China: A tool for Dualistic National Security.” Journal of China and International Relations. 2(1): 70-94.

Baker, Hugh. 1979. Chinese Family and Kinship. New York: Columbia University Press.

Brief Introduction of World Expo Shanghai. 2008. World Expo Shanghai 2010 Official Website. http://www.expo2010.cn/expo/expo_english/oe/bi/userobject1ai48695.html, accessed September 26, 2014.

Callahan, William. 2012 “Shanghai’s Alternative Futures: The World Expo, Citizen Intellectuals, and China’s New Civil Society.” China Information 26(2): 251-273.

China Daily. 2014. “Art Must Present Socialist Values: Xi.” China Daily, October 15. accessed February 12, 2016.

Cheng, Tiejun and Mark Selden. 1994. “The Origins and Social Consequences of China’s Hukou System. The China Quarterly. 139: 644-668.

Chong, Gladys Pak Lei. 2011. “Volunteers as the ‘New’ Model Citizens: Governing Citizens through Soft Power.” China Information 25(1): 33-59.

Connery, Christopher. 2011. “Better City, Better Life.” boundary 2 38(2): 207-227.

Ding, Sheng. 2012. “Is Human Rights the Achilles’ Heel of Chinese Soft Power? A New Perspective on Its Appeal.” Asian Perspective 36:641–665.

Duncan, Nancy. 2003. Landscapes of Privilege: The Politics of the Aesthetic in an American Suburb. New York: Routledge.

Economy, Elizabeth. 2004. The River Runs Black: The Environmental Challenge to China’s Future. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Escobar, Pepe. 2010. “Shanghai and the Mystery of China’s Soft Power.” Huffington Post. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/pepe-escobar/shanghai-and-the-mystery_b_564313.html, accessed September 26, 2014.

Fei, Xiaotong. 1947. From the Soil: The Foundations of Chinese Society. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Fotsch, Paul Mason. 2001. “The Building of a Superhighway Future at the New York World’s Fair.” Cultural Critique 48(1): 65–97.

Gill, Bates and Yanzhong Huang 2006. “Sources and Limits of Chinese ‘Soft Power’.” Survival 48(2): 17-36.

Greenhalgh, Paul. 1991. Ephemeral Vistas: The Expositions Universelles, Great Exhibitions and World’s Fairs, 1851-1939. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press.

He, Hilary Hongjin. 2012. “I Wish I Knew: Comprehending China’s Cultural Reform through Shanghai Expo.” In Timothy Winter, ed. Shanghai Expo: An International Forum on the Future of Cities. New York: Routledge, 44-53.

Heller, Alfred. 1999. World’s Fairs and the End of Progress: An Insider’s View. Corte Madera: World’s Fair Inc.

Houdart, Sophie. 2012. “A City without Citizens: The 2010 Shanghai World Expo as a Temporary City.” City, Culture and Society 3(2): 127-134.

Hsu, Sara. 2016. “China’s Urbanization Plans Need to Move Faster in 2017.” Forbes, December 28.

Hubbert, Jennifer. 2017. “Back to the Future: The Politics of Culture at the Shanghai Expo.” International Journal of Cultural Studies 20(1): 48-64.

Johnson, Ian. 2013a. “China’s Great Uprooting: Moving 250 Million into Cities.” New York Times, June 15.

2013b. “New China Cities: Shoddy Homes, Broken Hope.” New York Times, November 9. https://www.nytimes.com/2013/11/10/world/asia/new-china-cities-shoddy-homes-broken-hope.html

Kahn, Joseph and Jim Yardley. 2007. “As China Roars, Pollution Reaches Deadly Extremes.” New York Times, 26 August. accessed November, 11 2011.

Krupar, Shiloh. 2018. “Sustainable World Expo? The Governing Function of Spectacle in Shanghai and Beyond.” Theory, Culture & Society 35(2): 91-113.

Li, Tania. 2005. “Beyond ‘the State’ and Failed Schemes.” American Anthropologist 107(3): 383–94.

Lim, Louisa. 2010. “Critics Worry about Shanghai Expo’s Legacy.” All Things Considered, February 8. accessed May 9, 2012.

“Living the Dream.” 2010. The Economist, April 29. http://www.economist.com/node/16009079, accessed September 26, 2014.

Low, Setha. 2003. Behind the Gates: Life, Security, and the Pursuit of Happiness in Fortress America. New York: Routledge.

McAuliffe, Cameron. 2013. “’Better City, Better Life’? Envisioning a Sustainable Shanghai through the Expo.” In Timothy Winter, ed. Shanghai Expo: An International Forum on the Future of Cities. New York: Routledge, 54.68..

Mawdsley, Emma. 2009. “Enviromentality” in the Neoliberal City: Attitudes, Governance, and Social Justice. In: H. Lange and L. Meier, eds. The New Middle Classes: Globalizing Lifestyles, Consumerism and Environmental Concern. Dordrecht, London: Springer, 237-251

“Migrant Population in Shanghai Shrinks as city Caps Number.” 2016. Chinadaily.com, March 2. http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2016-03/02/content_23704321.htm

Mullich, Joe. 2010. “World Expo Jump-Starts Shanghai’s Plan to Become Global Economic Hub.” Wall Street Journal. http://online.wsj.com/ad/article/chinaenergy-expo.

Nordin, Astrid. 2012. “How Soft is ‘Soft Power’? Unstable Dichotomies at Expo 2010.” Asian Perspective 36: 592-613.

Nye, Joseph S., Jr. 2005. Soft Power: The Means To Success In World Politics. New York: Public Affairs.

Ong, Aihwa. 2011. “Introduction: Worlding Cities, or the Art of Being Global.” In Aihwa Ong and Ananya Roy, eds. Worlding Cities: Asian Experiments and the Art of Being Global. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 1-26.

Peng, Pu. 2010. “Shanghai Expo Playing Catch-up with Cost.” China.org.cn, August 10.

http://www.china.org.cn/travel/expo2010shanghai/2010-08/09/content_20669780.htm

Postrel, Virginia. 2010. “Shanghai Shangri-La?” Big Questions Online, July 27. accessed August 10, 2010.

Roy, Ananya and Aihwa Ong, eds. Worlding Cities: Asian Experiments and the Art of Being Global. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

Sassen, Saskia. 2005. “The Global City: Introducing a Concept.” Brown Journal of

World Affairs XI(2): 27-43.

Scott, James. 1998. Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition have Failed. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Sifferlin, Alexandrea. 2017. “Here’s How Many People Die from Pollution around the World.” Time.com, October 19. accessed January 27, 2018.

Silla, Cesare. 2013. “Chicago World’s Fair of 1893: Marketing the Modern Imaginary of the City and Urban Everyday Life through Representation.” First Monday 18 (11).

Sze, Julia. 2015. Fantasy Islands: Chinese Dreams and Ecological Fears in an Age of Climate Crisis. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Tilt, Bryan. 2010. The Struggle for Sustainability in Rural China: Environmental Values and Civil Society. New York: Columbia University Press.

United Nations. 2018. The World’s Cities in 2018. http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/urbanization/the_worlds_cities_in_2018_data_booklet.pdf

Wallis, Cara and Anne Balsamo. 2016. “Public Interactives, Soft Power, and China’s Future at and beyond the 2010 Shanghai World Expo.” Global Media and China 1(1-2): 32-48.

Wang, Jian. 2013. Shaping China’s Global Imagination: Branding Nations at the World Expo. New York: Palgrave MacMillan.

Wang Zhenghua and Qu Xiaozhen. 2007. “A Fresh Start for Shanghai’s Relocated Families.” China Daily, August 6.

Winter, Timothy. 2012. Shanghai Expo: An International Forum on the Future of Cities. New York: Routledge.

World Factbook. n.d. Washington, DC. Central Intelligence Agency.

World Bank. 2018. “Urban Population (% of Total).” United Nations Population Division. World Urbanization Prospects: 2018 Revision.

Zhang, Li. 2001. Strangers in the City: Reconfigurations of Space, Power, and Social Networks within China’s Floating Population. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Zukin, Sharon. 1992. “The City as a Landscape of Power: London and New York as Global Financial Capitals.” In Neil Brenner and Roger Keil, eds. The Global Cities Reader. New York: Routledge, 137-144.

Notes

Much of this commentary drew upon Joseph Nye’s concept of soft power. For scholarly analyses of soft power and the Expo, see Chong 2011, He 2012, Nordin 2012, Wallis and Balsamo 2016. A related study of the Expo and nation branding can be found in Wang 2013.

The staging and scale of the Shanghai Expo required an investment of fiscal and organizational resources that was also surely intended to leave foreign audiences with a strong sense of China’s growing power on the global stage.

Indeed, if one factors in visitors from Hong Kong and Macao, both under PRC governance, the numbers are even more striking.

While world’s fairs have long boosted the urbanization efforts of host cities and offered visions of urban idealism—think for example of the 1893 Chicago fair that Cesare Silla argues was both a place to trace the genesis of modern American urban life and a generator of its emergence (2013)—the Shanghai Expo laid claim to being the first to focus predominantly and purposefully on “issues of [the] city” (cited in Sze 2015: 133).

This figure does not include Hong Kong and Macao but does include migrant laborers (Hsu 2016; World Factbook n.d.). For a comparison of global rates of urbanization, see World Bank 2018.

These figures would arguably be even higher were the government to dismantle its hukou system that restricts migration and denies urban citizenship and its benefits to much of rural China. For example, the hukou system largely bars children of migrants from attending public schools, thus both limiting the population of youth and deterring potential adult migrants seeking jobs. For further discussion of the hukou system, constraints on urban growth, and the denial of urban citizenship and benefits to migrants, see Cheng and Selden 1994; Zhang 2001.

This is not to argue that Chinese citizens need convincing of the superiority of urban living. Indeed, the massive rural-urban migration patterns and the systemic migrations restrictions of state policy make clear both that domestic citizens desire to live in cities and that the state perceives unregulated urban growth as problematic to its development plan. What is suggested here rather is that the manifestations of China’s urban modernity are not uniformly perceived as positive and that this has implications for how the state draws upon the urban to construct the legitimacy of its development model.

The ethnographic portion of the research on which this article is based was conducted in China during the summers of 2009 and 2010, including ten visits of eleven to twelve hours each to the World Expo site, interviews with Expo visitors and Shanghai citizens, and follow-up interviews after the Expo closed in 2010 and 2011. Given the economic and political precarity of the migrant population in China who lack urban hukou and whose views of China’s urbanization schemes might be more critical, interviews were conducted solely with citizens with official registration permits and students. Both these groups are privileged by China’s urbanization model and have greater leeway to express criticism to foreign researchers.

For a discussion of the debates in China over whether policy ought to prioritize the quality of the natural environment or industrial revenue and wages, see Tilt 2009.

That this message was clearly received by visitors was confirmed by one local teacher, who told me as we meandered through the Expo, “The cities of the future have a lot of science and technology, and this will enable the growth of the natural environment…. The innovation of the Expo’s technology exemplifies how to build a green city whose existence will not threaten the sustainability of nature and will even be beneficial to the environment.” As McAuliffe (2013) notes, technological determinist visions of social futures have also been typical of earlier world’s fairs.

Yet, while the traditional paradigm drove construction of the building, the constitution of the generations—grandparents, parents, and one child—was a decidedly modern result of China’s one-child policy that was a fixture of Chinese policy from 1979 to 2015. The literature on the subject is extensive (see for example, Baker 1979; Fei 1947).

Forty percent is an official figure (“Migrant Population” 2016). The actual figure is arguably even larger.

Indeed, Christopher Connery goes so far as to argue that the Expo was the very raison d’etre for Shanghai’s massive urban reordering (2011: 207).

While the China Daily, the English-language government-sponsored newspaper claims a “fresh start” for these relocated families, “helped” by the government to “move from the shanty-town, notorious for its worn-down houses and poor transportation (Wang and Qu 2007), western media revealed how the state prioritized aestheticization over the rights of low-income residents, often forcibly removing them from homes without compensation or providing alternative housing. See for example Johnson 2013b.

This same Shanghai resident explained to me that in the period leading up to the Expo, the city of Shanghai ran a program called “600 Days” in which citizens could report a problem with the Expo to a local TV station that would air problems and work with the city to solve them. When I asked about what would happen with urban improvement schemes after the Expo, she laughed out loud and said the program would stop.

One scholar similarly called the Expo a “remedial class for Chinese people at the juncture of China’s incorporation in the global system” (He 2012: 53).

Ong goes on to argue that the Shanghai Expo was the “most explicit demonstration yet of a can-do determination to experiment with cutting-edge innovations in urban architecture, industry, and design” (2011: 2).