Abstract

Focusing on Ōnobu Pelican’s play Kiruannya and U-ko-san (2011), this article analyzes documentary theater from the area afflicted by the triple disaster of March 11, 2011. Kiruannya and U-ko provides a rich tapestry of the multiple and often contradictory features of Fukushima Prefecture in the aftermath of the Fukushima calamity, weaving a dense fabric of fictional material, newspaper clippings, and reality. I show that Ōnobu’s play opposes national discourses of a spatially limited disaster, and that it offers keen insights into the highly ambivalent and emotional landscape of those residents of Northern Japan, whose homeland was turned into a disaster zone and/or radioactive wasteland after 3.11.

Keywords: 3.11, culture of disaster, nuclear criticism, contemporary theater, documentary theater, regional theater, emotional healing (iyashi)

Introduction

This article provides a close reading of Kiruannya to U-ko-san (Kiruannya and U-ko, 2011), a documentary play by the playwright and director Ōnobu Pelican (b. 1975)1, which received high acclaim in Japan. Ōnobu lived in Minamisōma, a city heavily affected by the earthquake and ensuing tsunami, located 25 km north of the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant.2 Parts of the city were evacuated because of radiation, and many of the evacuees have still not returned to their homes. In the meantime, authorities have successively lifted evacuation orders (excluding the “difficult-to-return” zones, kikan konnan kuiki), to allow for the alleged return to normal in the disaster zone.3

In the first months after the earthquake, tsunami, and subsequent nuclear catastrophe, Ōnobu felt an urgent need to address the painful experiences of people affected, and decided to make these experiences the topic of his new play.4 This article examines the potentialities of documentary theater as a medium for processing trauma in post-disaster Tōhoku, and analyzes how Kiruannya and U-ko engages in the cultural work of transforming individual suffering into collective memory.5 Documentary plays enact negotiations between reality, its image, and its interpretation, and can thereby open up new approaches to one’s own reality, as Janelle Reinelt has argued.6 In her study on documentary theater, Carol Martin created a list of the functions of documentary plays.7 The following are particularly relevant in the context of this article: “1. To create additional historical accounts; 2. To reconstruct an event; 3. To intermingle autobiography with history.” In other words, besides helping people to overcome trauma, documentaries have the potential to trigger critical engagement and activism.8 I will return to this later.

In this article, I argue that the playwright constructs a narrative countering images of ‘Fukushima’ as a region of destruction and despair, one that can only be characterized by the disaster and its aftermath. He does this without neglecting contentious issues around the nuclear catastrophe or uncritically supporting slogans for quick recovery. While a critical stance is not rare for theater responding to the Fukushima calamity, Kiruannya and U-ko is unusual in addressing so many conflicting dimensions in response to the disaster. As I show in detail below, Ōnobu’s play allows those immediately affected to construct and re-experience trauma as a first step in assimilating these stressful events. At the same time, the narration addresses those living far away and invites them to relate emotionally to the traumatic experiences addressed. Kiruannya and U-ko criticizes the promotion of economic growth at the expense of the local population’s livelihoods, and leaves sufficient room for them to mourn for what is lost.

A multifaceted Fukushima – Conflicting images of the beloved homeland

Kiruannya and U-ko premiered at the Subterranean Theater in Tokyo in June 2011,9 directed by the author and performed by his troupe Manrui Toriking Ichiza (Loaded Bases Bird King Troupe),10 which shifted its base of activities from Minamisōma to Fukushima City due to the calamity. After the Tokyo premiere, the play was presented in other Japanese cities.11 Kiruannya and U-ko was discussed positively in national theater journals and nominated as “play of the month” by the renowned Performing Arts Network. Subsequently, Ōnobu gained visibility on the Tokyo theater scene, becoming a frequent guest in panel discussions on Japanese theater after 3.11, as well as a participant in round table discussions addressing the Fukushima calamity.

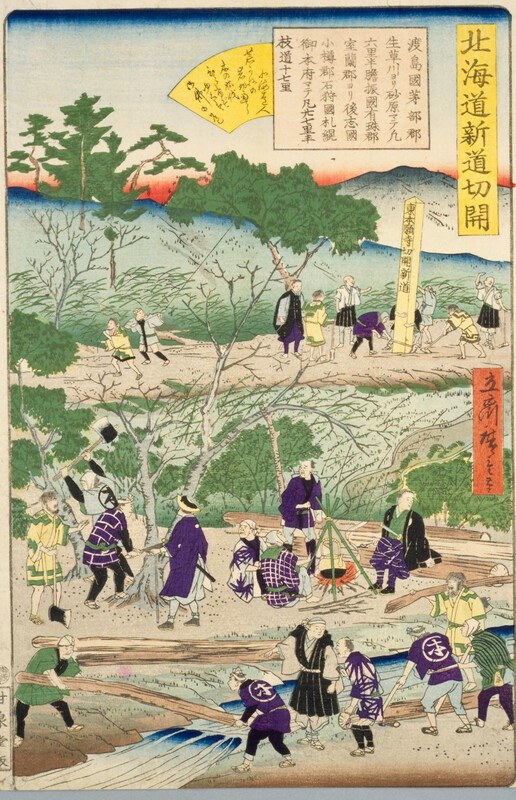

|

Ōnobu Pelican Kiruannya and U-ko (Courtesy of Akai Yasuhiro) |

Kiruannya and U-ko centers on the ambivalent emotions of people living in the areas affected by the tsunami and/or the nuclear exclusion zone in the immediate aftermath of the disaster, and provides an account of Fukushima Prefecture’s history, beginning in 2011 and going back to the beginnings of the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant in 1970. The play is a collage of newspaper article readings and quotes from literary texts bound together by a fictive narrative of two women and a man searching for a woman called U-ko. However, each of the three figures in the play, called Man, Woman 1, and Woman 2, seem to be looking for a different person: a childhood friend, an acquaintance met on the World Wide Web, or the chef of a bistro. Her name is written with the U in romanization and the latter half in a Chinese character, but is pronounced Yūko. U-ko lives in a town where the newspaper deliveryman Kiruannya scatters clippings from old newspapers all over town. The nickname, a combination of kiru (cut, kill) and annya (older brother; Fukushima dialectal word for a friendly male who is older than the speaker), refers to this very activity. I will come back to the relevance of both names later.

The repetitive character of these episodes evokes flashbacks experienced by individuals suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder. The play evokes the return of a repressed trauma experienced by those who were searching for family members, friends, and acquaintances in the aftermath of the disaster, often unsuccessfully. The term ‘trauma’ refers to an experience of extreme intensity that overstrains the coping capabilities of an individual and causes lasting damage to his/her self-conception. However, what is perceived as a traumatic experience is not the event itself, but the persisting re-experiencing of it.12 A traumatic experience is thus temporally and spatially separated from the triggering event (latency). The ‘embodied’ memory is not directly accessible and cannot be narrativized.13 Narrativizing the dreadful events, and allowing viewers to re-experience and construct their trauma is a major task of the play.

Ōnobu’s stage design and effects are minimalist. The stage is completely covered by newspaper clippings and is dominated by the model of a village hanging at its center, symbolizing the town where the newspaper deliveryman Kiruannya and U-ko, the person sought in the play, live. Although the two figures are central to the play, they do not appear on stage. Classical music, including famous pieces such as Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata and Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake, set the contemplative tone of the play. Although Kiruannya and U-ko consists largely of characters quoting newspapers and literary material, it is not a static performance. As the man and the two women move around the village model at center stage, the tempo of the figures’ movements and speech increases with their growing despair and desperation, generating a spiral of dynamism. The actors are moving around frantically, calling out U-ko’s name, as well as the dates and places where she was last seen or lost. The affective dimension of the calamity becomes tangible even to audience members who lack direct experience of the dreadful events. The play invites the audience to actively connect with the emotions triggered by the disaster, and hence stimulates them to engage with the trauma. In some audience members, this might be the starting point for re-thinking their own stance towards the use of nuclear power or their private energy consumption.

Ōnobu Pelican Kiruannya and U-ko, revised version (Courtesy of Akai Yasuhiro)

The actors alternatively read newspaper clippings about a person named U-ko that are scattered across the stage. They start in January 2011, and proceed in chronological order. When the man calls out the date of March 11, the review of everyday local events is suddenly interrupted by an Early Earthquake Warning siren evoking haunting memories of the calamity in actors and audiences alike, including the anxiety and uncertainty caused by the numerous aftershocks that lasted for weeks. In his review of the play, Masaki Hiroyuki (b. 1964), the Tokyo-based former editor-in-chief of the journal Theatre Arts (Shiatā Ātsu), writes about his involuntary reactions to the sound of the Early Earthquake Warning, and the shock that gripped his body when he saw the play about six months after the catastrophe.14 When the three actors resume reading the newspaper clippings, they refer to the disaster. Again, it is U-ko who is the protagonist, and who represents the local people’s various reactions and behaviors, such as an evacuee taking neighbors out of the radiation zone in her bus, a mayor encouraging villagers to return and get involved in reconstruction, and a woman complaining to the visiting prime minister about living conditions in temporary shelters. When the actors finally read out the Fukushima Police Department’s list of missing people whose bodies were identified, again, all of them are named U-ko. It becomes ever more uncertain who U-ko is, and if she ever existed at all.

The quest to find U-ko invites the audience to relive the fraught days after 3.11 as people desperately searched for missing relatives and friends. By making the dominant color of the stage, including the performers’ clothing, white, Ōnobu opens up a wide space for imagination. What is presented on stage is not limited to a specific historical time or geographic place such as “Fukushima.” Audiences are encouraged to imagine themselves in the position of the two women and the man in their search for U-ko. Her name is telling: while U can be read as referring to the unknown, the name’s Japanese pronunciation also suggests the English personal pronoun “you.” Moreover, Yūko is a very common Japanese female name, which can be written with a number of different Chinese characters. U-ko represents the countless people who are still missing to this day, and gives the nameless victims an identity. At the same time, U-ko stands for everywoman: she reminds us that everyone could find themselves in her situation. Thus, in Kiruannya and U-ko, which was first conceived to be performed in front of a Tokyo audience, Ōnobu is invested in the cultural work of creating an imagined community affected by the calamity that is not limited to those living in the immediate disaster zones. Differentiating between individual and collective trauma, Alexander and Breese argue that “for collectivities […] it is a matter of symbolic construction and framing, of creating a narrative and moving along from there. A ‘we’ must be constructed via narrative and coding, and it is this collective identity that experiences and confronts the danger.”15 Events have to be expressed and constructed as trauma to be perceived as such by a group of people. By actively inviting audiences far removed from Tōhoku to imagine themselves in the position of those directly affected, Ōnobu counters national narratives of 3.11 as a geographically limited disaster and a short-term recovery.

A number of times, the quest to find U-ko is interrupted by readings of citations from local literature, which are distributed among the three actors and establish a new level of involvement with issues related to 3.11. The first reading cites the entire Episode 99 of Tōno monogatari (The Legends of Tōno),16 a record of folk legends that were orally transmitted through the generations in the Tōno region, which is located near the Pacific coast of Iwate Prefecture, one of the areas most severely affected by the triple disaster. Yanagita Kunio (1875–1962), the founder of Japanese folklore studies, collected these legends based on the memory of the Tōno native Sasaki Kizen (or Kyōseki, 1886–1933). The resulting book is a rewriting of local oral history into a literary work that addresses a national audience and engages with the problems of Japanese collective identity in the modern world. Subsequently, Tōno as described in the legends became the canonical representative of the Japanese homeland (furusato)17 in the collective imagination.

Episode 99 relates the story of Kitagawa Fukuji, who lost his wife and one of his children in the devastating tsunami of 1896. Living in a temporary shelter with his surviving children, he got up one moonlit night and encountered the ghost of his dead wife. While crying about the loss of her children, Kitagawa’s wife also reports that she has found a new partner. Although Tōno monogatari relates the very basic facts of the event fleetingly, it nevertheless succeeds in conveying the emotional vividness of the protagonist. This is even more the case if one reads episode 99 in the context of the Fukushima calamity. Mirroring the situation of recent disaster victims who lost close family members, the text conjures up accounts of wandering spirits of people who died in the tsunami.18 Describing the encounter between the living and the dead, and at the same time hinting at the possibility of finding peace in the afterlife, the scene reveals what survivors of the triple disaster might long for. For those not directly affected, the episode is also deeply disturbing, thereby emotionally drawing spectators far removed from Tōhoku into the play and inviting them to imagine the process of mourning experienced by survivors. Moreover, by adding a passage pertaining to a local disaster from an account from over one hundred years ago, Ōnobu links 3.11 to the past, emphasizing the fact that Northern Japan has a long and tragic history of devastating tsunami disasters, and questioning the unpredictability (sōteigai)19 of the nuclear disaster as frequently claimed to obscure the human responsibility for the Fukushima meltdowns. Tōno and Tōno monogatari, both epitomizing the Japanese homeland, again highlight the relevance of the tragic events beyond the spatially limited confines of the disaster area.

Kiruannya and U-ko draws a multifaceted picture of Fukushima Prefecture before and after the devastating events via the reading of extracts, not all of which mention the topic of disaster, from various kinds of sources – quoting well-known literary works, as well as local newspaper reports.20 The information mined for the performance mainly deals with local events and politics: agricultural reports, coverage of local sports and cultural happenings, and crime reports. The broad variety of topics is needed, not only to paint a full picture of the locale before the disaster, but also to contrast with the chronological record of significant occurrences in the history of the region’s nuclear power industry – a history that is intertwined in the local reportage. For a post-3.11 audience, the latter stand out against the majority of rather trivial local events. The play traces the prefecture’s development into one of the country’s major energy suppliers, without omitting the attempts of Japan’s most powerful utility and the operator of Fukushima Daiichi, TEPCO (Tokyo Electric Power Company), to cover up problems in Fukushima’s nuclear reactors.

Ōnobu also provides information on the region’s overall development, such as the opening of new train routes or school buildings, highlighting the fact that the high-risk technology of the nuclear industry was established in the region to trigger economic growth in a rural, less developed and sparsely populated area. This also hints at the fact that locals might have willingly accepted the dangers of nuclear power in favor of jobs and socio-economic development, which became a source of ambivalence and tension after the disaster. Locals may still be reluctant to criticize the nuclear industry for causing the calamity, since their livelihoods depended on the nuclear plant. What is more, criticizing the use of nuclear power would entail a re-evaluation of their own involvement.

Kiruannya and U-ko addresses the whole complexity of problems that led to the Fukushima calamity. As the theater critic Masaki has done, the play can be interpreted as showing the author’s embitterment, perhaps even an accusation, towards the inhabitants of Tokyo for heaping the risks in meeting the capital’s energy needs onto the people of Fukushima Prefecture. Certainly, Ōnobu criticizes what has been called gisei no shisutemu (“sacrificial system”)21: companies and policyholders assigning the tremendous risks of nuclear energy to peripheral regions such as northern Japan, whose safety and future are jeopardized for the benefit of the metropolitan center. However, I would suggest a more complex reading of the narrative. Besides taking a critical stance towards parties responsible for the development of the nuclear energy industry in Tokyo and Fukushima Prefecture, the play draws a positive, even affectionate image of Onobu’s home province, with its abundant natural and attractive cultural heritage. For example, the performance touches on the establishment of Oze National Park in 2007, which stretches across Fukushima, Gunma, Niigata and Tochigi Prefectures, and the Sōma Nōmaoi, a designated cultural treasure of Japan, which involves an annual horse race organized by three shrines in Fukushima Prefecture, where the participating riders wear historical costumes. Ōnobu joins other local artists and cultural initiatives such as Wagō Ryōichi and Project Fukushima!22 in an effort to counterbalance post-disaster images of Northern Japan that reduced the afflicted areas to mere disaster zones. Both aim at countering the stigmatization, which reinforces the already existing marginalization of the aging, rural prefecture of Fukushima. However, Ōnobu goes one step further. Via commentary on local politics, festivals and landscape, Ōnobu provides insight into the complex emotional state of the local people: traumatized by loss and bereavement, affected residents are torn between charges against those responsible in the capital, self-accusations, and the love of and pride in their homeland.

While the Japanese government and the nuclear power industry have targeted such remote, less developed areas that depend on the jobs and subsidies brought by hosting nuclear facilities, local people assented and accepted the dangers of nuclear energy in exchange for jobs and modest prosperity.23 Although national stakeholders pushed nuclear power forward by emphasizing its safety (anzen shinwa), it must be assumed that there was a certain level of willing ignorance on the part of the local community. Having said that, we also have to consider that in the late 1960s and early 1970s, a strong anti-nuclear power movement to mobilize citizens did not exist in rural Japan or, indeed, almost anywhere in the world. Now, as a consequence of the nuclear disaster, the homes and livelihoods of numerous people, as well as many of the region’s natural and cultural assets, which were important components of local identity, are lost and might never be regained. The readings of newspaper excerpts intertwined in the play provide local reportage highlighting all these aspects. Kiruannya can be read as the very embodiment of the calamity: kiru, written in the katakana syllabary writing system, hints at two possible Chinese characters, meaning ‘cut’ or ‘kill’, thereby evoking associations comparable for a Western audience to the Grim Reaper wandering about town to collect the dead.24 Spreading the clippings all over town, he also symbolizes the ceaseless process of coming to terms with the complex emotional state of affected residents, as well as the flashbacks related to the experience of trauma.

Ōnobu highlights the beauty and value of what has been lost, when using the following two poems, which are emotionally charged representations of Fukushima Prefecture, in his play. Fukushima-ken Futaba-gun Kawauchi-mura (Kawauchi Village in Futaba District, Fukushima Prefecture),25 by the Fukushima-born poet Kusano Shimpei (1903–1988),26 presents an idyllic picture of life in the countryside with rich wildlife and a vibrant community, all the while emphasizing the uniqueness of the village. By making the poet’s reed hut and second home a place of exile and retreat from the noisy life of the city, Kawauchi-mura is imagined as an alternative to living in the city. When the poet imagines himself to be back there one day after temporarily leaving for Tokyo, theater audiences are painfully reminded that returning home will no longer be possible for many people displaced by the Fukushima calamity.

The second poem quoted in Ōnobu’s play, Juka no Futari (Two People Under A Tree), by the well-known poet, sculptor, and painter Takamura Kōtarō (1883–1956),27 strikes a similar chord to Kusano Shimpei’s text. Juka no Futari is a hymn to Fukushima’s natural beauty. The beauty of Mount Atatara and the glistening of the River Abukuma are invoked several times through the poem, acting as a refrain and setting the scene. Takamura links his praise of the region with the treasured memories of his late wife Chieko (1886–1938), a Fukushima-born painter and poet herself, who died from tuberculosis after a long-term mental illness. In the context of Kiruannya and U-ko, the poem, written on March 11, 1923, gains a new meaning. Besides evoking the calamity by the very date of its composition, the inscription of the poem into the performance triggers associations of the survivors’ emotional distress from outliving family members and/or friends lost in the disaster. At the same time, the poem mourns the fact that places deeply linked to the private memories of people living in the afflicted areas are now polluted by radiation for the foreseeable future.28

Kiruannya and U-ko was not performed in Fukushima City until November 2012, nearly a year and a half after its premiere in Tokyo. At a symposium called the Earthquake Disaster and Theatre: Asking for a New Paradigm for Theatre, held on October 8, 2012 in the Za Kōenji theater in Tokyo,29 Ōnobu talked of his hesitation about staging the play in his home prefecture, and expressed his concerns about finding a different approach to the disaster – particularly, one that takes into account the emotional distress of affected people, without glossing over contentious issues.30 He voiced his concerns that the play might be criticised for contributing to fūhyō higai,31 harmful, unfounded rumors, allegedly spread about affected areas in the aftermath of the disaster. Fūhyō higai is a highly controversial issue persistent in public discourse on the Fukushima calamity. On the one hand, rumors arise when reliable information is unavailable in the event of disaster, and reports on wide areas made virtually uninhabitable by radiation constitute both a substantially pragmatic and emotional burden for locals. However, allegations of fūhyō higai became a powerful tool in the hands of pro-nuclear pressure groups, including the Abe government, to silence critical voices warning of the risks of nuclear power and especially the risks to those returning to the contaminated land.

In this kind of environment, the danger of self-censorship in the arts is very real. However, experiences in the course of rehearsals made Ōnobu change his mind and present the play in Fukushima City. What initially proved to be emotionally challenging for the troupe, since many people from their immediate environment had died or were forced to live in contaminated places, evolved into a way to overcome emotional distress. The troupe’s experience of emotional healing (iyashi) lent impetus to the idea of performances with the aim of inducing a similar process in local audiences.32 Shows in Fukushima in 2012 were well received with emotional responses.33 Ōnobu was confronted with hardly any of the reproaches of fūhyō higai (harmful rumors) that were voiced so readily in the aftermath of the disaster. A major reason might have been that his play does not overlook the locals’ strong bond to their native land.

‘Fukushima’: progress and disaster

In winter 2013, about two and a half years after its Tokyo debut, Kiruannya and U-ko was restaged in Tokyo and Shizuoka in a slightly revised version under the direction of Akai Yasuhiro (b. 1972).34 The Fukushima City native was the director and head of the Tokyo-based theater Subterranean, where the original and revised versions of the play premiered. In the new version, the original text remains largely unchanged. The only difference was the inclusion of a “woman from 1970,” who makes her appearance in an exaggeratedly happy march to the tune of Minami Haruo’s Sekai no kuni kara konnichiwa (Hello From the Nations of the World), the official theme song of the Osaka Expo of the same year. The song sets the naïvely positive atmosphere of the short scene. The design of the woman’s dress (she wore a white T-shirt with red vertical patterns down both sides of the front and a golden party hat) was reminiscent of Okamoto Tarō’s (1911–1996) Taiyō no Tō (Tower of the Sun), one of the most famous works by the avant-garde painter and sculptor, and the symbol of Expo 70. Part of the Osaka Expo’s central festival plaza, the Tower of the Sun was a representation of the past (lower part), present (middle part), and future (the face) of humankind.35 Consequently, her dress identifies the “woman from 1970” as a personification of the year of the first World’s Fair held in an Asian country and hints at her being a link between past, present, and future in the play. I will return to the latter aspect shortly. Besides Okamoto, numerous other writers, artists and architects participated in shaping the image of the Expo, which was a “locus of both collaborative and contending ideas about the future.”36 “Progress and Harmony for Mankind” (Jinrui no shinpo to chōwa), the theme of the exposition, included praise of nuclear power as a new technology that was supposed to bring about a bright future for the whole world.37

|

Ōnobu Pelican Kiruannya and U-ko (Courtesy of Akai Yasuhiro) |

Marching in time to Minami Haruo’s song and providing a cheerful picture of the Expo’s opening ceremony, the woman in search of the future arrives in the town where U-ko and Kiruannya live. However, she does not interact with the characters searching for U-ko, preferring to observe the events that unfold on stage. The “woman from 1970” reads excerpts from the official record of the two Osaka Expo time capsules buried adjacent to Osaka castle, containing 2,098 objects “representing the achievements of our civilization and the everyday experience of the Japanese people,”38 which are to be excavated in 5,000 years. What was once a proud symbol of the cultural and technological advancement of humankind has turned into an icon of the long-term nuclear legacy after 3.11. The woman in the Osaka Expo’s dress quotes at length from a letter by a schoolboy addressed to people 5,000 years in the future. To contemporary ears post-2011, the letter reads like a science fiction fantasy; an idealistic enthusiasm for future potentialities carried to the extreme.

Short episodes featuring the “woman from 1970” are repeatedly interspersed in the play. She seems to pop up like an unpleasant memory of the careless acceptance of the risks of nuclear power that cannot be suppressed. Akai emphasized her role as a startling intruder by means of lighting. She sits on a little platform in the corner of the stage, occupying the spotlight when quoting from the Expo’s official records. Her naïve cheerfulness is in sharp contrast to the growing despair of the characters in their quest to find U-ko, which underlines the absurdity of her lines. Thus, the “woman from 1970” embodies the naïve faith in science and technology, and is a spirit haunting the future that had been imagined so brightly by her generation.39 Furthermore, by handing over the three literary texts examined above for her fellow actors to quote, she visibly acts as a mediator between different periods of time and hints at how Kiruannya and U-ko integrates the Fukushima disaster into a wider historical frame.

However, the play casts doubt on whether humankind will be able to learn the lessons of the past. In 1970, man-made disasters such as the Minamata disease were common knowledge. Yet attitudes towards science and technology – specifically as having the answers to all of life’s challenges – have changed little over the last four decades. Moreover, the problems and dangers of nuclear power are not resolved yet. It is only a matter of time until the next nuclear disaster occurs in some part of the world. Akai intended to highlight this universal aspect of Kiruannya and U-ko. Unlike the original, the revised play was performed by a cast of Tokyo actors and a Korean actress, whose role was to provide Korean language; she read the history of four decades of Fukushima Prefecture mentioned above, and Japanese subtitles were provided. By employing the Korean actress, Akai aimed at moving further away from the local focus of the play, and universalizing its subject.40 The problems and risks connected to the use of nuclear power do not end with the Fukushima calamity. Akai wanted to hint at the fact that a similar calamity is not unlikely to happen in one of Japan’s neighboring countries using nuclear energy. Thus, through the combined efforts of the playwright and the new director, the global dimensions of the play, together with the criticism of humankind’s blind faith in technology and science, become more explicit.

On the occasion of the fourth anniversary of the Fukushima calamity, the new version of the play was performed in translation in Munich by the German-Japanese theater collective EnGawa, under the directorship of Satō Otone.41 Although an original production in its own right, Kiruannya to U-ko-san – Bruder Sense und Frau U (Kiruannya and U-ko – Brother Scythe and Mrs. U)42 owes many staging details to the Japanese version. Performed in German with only a very few lines recited in Japanese, it likewise highlighted the global dimension of the issues touched upon in the play. The troupe’s cross-cultural performance is also reflected in the title of the play, which keeps the Japanese original with the German translation. As the Munich performance demonstrates, Kiruannya and U-ko has the potential to be shown internationally.

Conclusion

Weaving a dense fabric of fictional material, newspaper clippings and reality, Kiruannya and U-ko provides a rich tapestry of the multiple and often contradictory features of Fukushima Prefecture in the aftermath of the triple disaster. Ōnobu’s play offers keen insights into the simultaneous ambivalence and highly emotional landscape of those residents of Northern Japan, whose homeland was turned into a disaster zone and/or radioactive wasteland after 3.11. Although the numerous cross-references to local issues or literary quotes make the play particularly rewarding for a local or a Japanese audience, it can nevertheless be appreciated by international spectators, as the Munich performance has shown.

Kiruannya and U-ko works at two overlapping symbolic levels: one level offers local audiences a temporary space to process individual trauma, and experience emotional healing. Interweaving autobiography with history, the play encourages audiences to reconstruct the terrible events, a major function of documentary theater, as Carol Martin has outlined. The other level creates an alternative reading of the calamity, and constructs a narrative resisting the dominant image of Fukushima as a nuclear wasteland and as a geographically limited disaster. Kiruannya and U-ko integrates the March 11 disaster into the larger historical context of Northern Japan as a region known for devastating tsunami disasters, as well as into the establishment of the nuclear industry in Japan, and points to the shared responsibility of national and local stakeholders. The play moves viewers beyond the temporally and spatially limited confines of the disaster to integrate audiences into an imagined collective of people traumatized by this calamity that has its origins far beyond the borders of those areas immediately affected. Opposing national discourses of a disaster limited to a particular area, Ōnobu engages in transforming individual trauma into collective memory, thereby involving the diverse perspectives of Fukushima residents.

Acknowledgements: I would like to thank Ōnobu Pelican and Akai Yasuhiro for providing me with DVD material, a recording of the performances, and photos. I am much obliged to the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science for providing me with the funding to conduct research in Japan. I also thank the reviewers for their insightful and helpful suggestions.

Notes

Ōnobu P. Kiruannya to U-ko-san. Shiata Ātsu 48, 2011, pp. 121–138. See also Performing Arts Network (The Japan Foundation). Play of the Month. Kiruannya and U-ko. Pelican Onobu [online] (March 30, 2012). Available here, accessed: July 19, 2018.

For further detail on the situation on site, see, for example, McNeill, D. and Quintana, M. Mission Impossible. What Future Fukushima? The Asia-Pacific Journal, 11 (39), 1 [online] (September 30, 2013). Available from here, accessed: October 12, 2018. McNeill and Lucy Birmingham show how local people dealt with the earthquake, tsunami, and following nuclear disaster. McNeill, D. and Birmingham, L. Meltdown: On the Front Lines of Japan’s 3.11 Disaster. The Asia-Pacific Journal, 9 (19), 2 [online] (May 9, 2011). Available here, accessed: October 12, 2018.

Fukushima Prefecture provides up-to-date information on the transition process, accessed: October 12, 2018.

Sakate Y., et al. Shinpojiumu shinsai to engeki: Atarashii engeki paradaimu o motomete (Tokushū shinsai to engeki). Shiatā Ātsu 53, 2012, pp. 5–6.

See DiNitto, R. Narrating the Cultural Trauma of 3.11: The Debris of Post-Fukushima Literature and Film. Japan Forum, 26 (3), 2014, pp. 340–360 for a revealing study of these issues in the context of literature.

Reinelt, J. The Promise of Documentary. In: A. Forsyth and C. Megson, eds. Get Real: Documentary Theatre Past and Present. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009, pp. 9–11 and pp. 22–24.

In some cases, the political dimension of documentaries becomes more explicit in film, as in the work of Kamanaka Hitomi. In a recent interview with Hirano Katsuya, she raises similar issues to the ones I will discuss here. However, the scope of her work goes far beyond the realm of the risks of nuclear power. Kamanaka H. and Hirano K. Fukushima, Media, Democracy: The Promise of Documentary Film. The Asia-Pacific Journal, 16 (16), 3 [online] (August 15, 2018). Available here, accessed: October 12, 2018. See also the accompanying essay by Margherita Long.

Long, M. Japan’s 3.11 Nuclear Disaster and the State of Exception: Notes on Kamanaka’s Interview and Two Recent Films. The Asia-Pacific Journal, 16 (16), 4 [online] (August 15, 2018). Available from: https://apjjf.org/2018/16/Long.html, accessed: October 12, 2018.

On June 25 and 26 as part of the SENTIVAL! at atelier SENTIO festival. See the trailer here, accessed: June 19, 2018.

Ōnobu founded the troupe in 1996 when he was a student at Fukushima University. In January 2015, Manrui Toriking Ichiza was renamed Shia Torie (THEA TRiE). See the troupe’s homepage, accessed: June 19, 2018.

Kiruannya and U-ko was then performed in Sendai (September 17 and 18, 2011) and Yokohama (September 24 and 25, 2011), followed by readings in Aomori (January 21, 2012), Kitakyūshū (March 10, 2012) and Fukushima City (November 17 and 18, 2012).

Nünning, A., ed. Metzler-Lexikon Literatur- und Kulturtheorie: Ansätze, Personen, Grundbegriffe. Stuttgart: Metzler, 2008, p. 728.

In her influential rereading of Freud, Caruth describes this paradoxical nature of traumatic experience as follows: “Trauma is not locatable in the simple violent or original event in an individual’s past, but rather in the way its very unassimilated nature – the way it was precisely not known in the first instance – returns to haunt the survivor later on.” Caruth, C. Trauma: Explorations in memory. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, 1995, pp. 3–4.

Masaki H. Sabuterenian purodyūsu ‘Kiruannya to U-ko-san’ [online]. Wonderland, 2014. Available from here, accessed: June 19, 2018.

Alexander, J. C. and Breese, E. B. On Social Suffering and Its Cultural Construction. In: R. Eyermen, J. C. Alexander, and E. B. Breese, eds. Narrating Trauma: On the Impact of Collective Suffering. Boulder and London: Paradigm Publishers, 2011, pp. xii–xiii.

Yanagita K. Tōno monogatari. Yanagita Kunioshū. Nihon kindai bungaku taikei (NKBT) 45, 1973, pp. 299–300. Tōkyō: Kadokawa shoten. References to the Tōno monogatari also appear in some literary works on the Fukushima calamity. See the forthcoming book DiNitto, R. Fukushima Fiction: The Literary Landscape of Japan’s Triple Disaster. University of Hawaii Press, 2019.

Ivy, M. Discourses of the vanishing. Modernity, phantasm, Japan. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995, p. 100.

Parry, R. L. Ghosts of the Tsunami. London Review of Books [online], 36 (3), February 6, 2014, 1–11. Available from here, accessed: June 19, 2018.

For a critical discussion of the alleged unpredictability of the Fukushima disaster, see Samuels, R. 3.11: Disaster and Change in Japan. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2013, pp. 35–39.

Takahashi, T. Gisei no shisutemu – Fukushima, Okinawa. Tokyo: Shūeisha, 2012. For an in-depth analysis of another play invested in this issue see Geilhorn, B. Local Theatre Responding to a Global Issue – 3/11 seen from Japan’s Periphery. Japan Review 31, 2017, pp. 123–139. Available from here, accessed: June 19, 2018.

Iwata-Weickgenannt, K. Precarity Beyond 3/11 or ‘Living Fukushima’: Power, Politics, and Space in Wagō Ryōichi’s Poetry of Disaster. In: K. Iwata-Weickgenannt and R. Rosenbaum, eds. Visions of Precarity in Japanese Popular Culture and Literature. London and New York: Routledge, 2015, pp. 187–211. See also the project’s homepage, accessed: June 19, 2018.

Aldrich, D. Networks of Power. Institutions and Local Residents in Post-Tōhoku Japan. In: J. Kingston, ed. Natural Disaster and Nuclear Crisis in Japan. Response and Recovery after Japan’s 3/11. London and New York: Routledge, 2012, pp. 127–139.

This is why Otone Sato chose Kiruannya to U-ko-san – Bruder Sense und Frau U (Kiruannya and U-ko – Brother Scythe and Mrs. U) as the title for the German version of the play, which I will briefly touch upon later.

Kawauchi-mura is situated in the 20–30 km zone around the Fukushima nuclear plant. While the town was initially subject to mandatory evacuation, it is part of the area that was eventually opened up by authorities. These details are not made explicit to the audience, but will be known to locals.

Kusano Shimpei, born in Kamiogawa (Fukushima Prefecture) is one of the major Japanese poets of the twentieth century and particularly known for his lyric poems about nature.

Takamura K. Chieko shō. Tōkyō: Shinchōsha, 1967, pp. 65–67. Takamura Kotaro was an outstanding poet of his time and, among others, crucial to the establishment of shintaishi (new style of poetry that was no longer limited to the combination of verse of five or seven syllables common in traditional poetry) in the vernacular language. Two People Under A Tree is part of his most prominent collection of poems, Chieko shō (a selection of writings on Chieko, first published in 1941), which comprises works from the very beginning of their relationship until well after Chieko’s death. For an English translation, see here, accessed: June 19, 2018.

The area referred to in this poem is situated outside the mandatory evacuation zones. However, it remains to be seen what long-term effects the radiation exposure will have on residents.

For a close reading of Okada Toshiki’s play Genzaichi (Current Location), which addresses the problem of fūhyō higai in a fictionalized form, see Geilhorn, B. Challenging Reality with Fiction – Imagining Alternative Readings of Japanese Society in Post-Fukushima Theatre, in B. Geilhorn and K. Iwata-Weickgenannt, eds. Negotiating Disaster: ‘Fukushima’ and the Arts. London and New York: Routledge, 2017, pp. 162–176.

From November 29 to December 3 at Sabuterenian in Tokyo and on December 5 and 6 at Atorie Mirume in Shizuoka. For further information, see the theater’s homepage, accessed: June 19, 2018.

Gardner, W. O. The 1970 Osaka Expo and/as Science Fiction. Review of Japanese Culture and Society 23, Expo ’70 and Japanese Art: Dissonant Voices, 2011, p. 28. [online] Available from here, accessed: June 19, 2018.

To be sure, organizers were absolutely aware of the numerous problems around the globe and the Expo’s exaggeratedly positive mode did not escape criticism and ridicule from contemporaries, as Gardner has shown. But critical voices were mitigated and pushed to the margins (see Gardner, p. 38).

Panasonic, 2010. Time Capsule Expo ’70. A gift to the people of the future from the people of the present day… [online]. Available from: http://panasonic.net/history/timecapsule, accessed: June 19, 2018. In the list of contents you can find a Plutonium timekeeper, Radioactive carbon C14, Plutonium Pu239, which is used for the production of nuclear weapons, and scientific reports for the future, including one on atomic science, but also records of the atomic bombings. Obviously, the people responsible did not realize the conflict between the remembrance of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the promotion of nuclear technology for energy supply.

Interestingly, Okada Toshiki’s Unable to See, which was shown at The World is Not Fair – The Great World’s Fair 2012 festival in Berlin, also employs references to the Osaka Expo in what was one of his first attempts to address the Fukushima calamity on stage. However, as a satirical piece displaying strong irony and sarcasm, it is very different in character. For more details, see Geilhorn, Challenging Reality.

The theater collective was formed on the occasion of the Fukushima calamity and has presented related performances on its anniversary since 2012.

Ōnobu P. Bruder Sense und Frau U [online]. Aus dem Japanischen von Otone Sato. Munich: Teatralize.company, 2014. Available from here, accessed: June 19, 2018. The play was staged between March 13 and 15, 2015, and included a talk after the performance (on March 14) with the director and the following Japanese guests: Nishidō Kōjin (renowned Japanese theater critic and president of the International Association of Theatre Critics), Takahashi Shinya (theater specialist and professor of German studies at Chūō University, Tokyo) and Akai Yasuhiro. The performance was part of a cultural event lasting several days.

For further details, see Leucht, S. Neuanfang unter Kirschblüten. Vor vier Jahren havarierte im japanischen Fukushima das Kernkraftwerk. Zwei Veranstaltungen erinnern im I-Camp an die Katastrophe und weisen in die Zukunft. Süddeutsche Zeitung (Bayern – Kultur), March 11, 2015 and EnGawa. Kiruannya to U-ko-san – Bruder Sense und Frau U. EnGawa [online]. Available from here, accessed: June 19, 2018. See the trailer.