Few personalities in world history have had a more compelling personal story or a greater impact on the world than Temüjin, who rose from destitute circumstances to be crowned as Chinggis Khan in 1206 and became the founder of the world’s greatest contiguous land empire. Today, eight and a half centuries after his birth, Chinggis Khan remains an object of personal and collective fascination, and his image and life story are appropriated for the purposes of constructing national identity and commercial profit.

Vilified as a murderous tyrant outside his homeland, yet celebrated by the Mongols as a great hero and object of cultic worship for centuries,1 Chinggis Khan’s reputation underwent an eclipse even in Mongolia when it fell under Soviet domination in the early twentieth century. In order to weaken Mongol nationalism and integrate Mongolia into the Soviet Union (and later its East European allies), the Soviets dictated that Chinggis Khan become an unperson, portrayed in the darkest hues if at all – a move accompanied by the suppression of Tibetan Buddhism and other cultural policies, undermining the ethnic identity of the Mongols. The Communists attempted to create a new sense of nationhood based on the glorification of the Mongol land and of Communist revolutionaries.2

Six decades of Soviet domination in Mongolia finally ended with the fall of the Berlin Wall, which then led to the one-party rule system yielding to the first multi-party elections in 1990. Young Mongolian democrats demanded the revival of traditional Mongolian culture, the reintroduction of the traditional Mongol script (which had been replaced by the Cyrillic script), the rehabilitation of Chinggis Khan, and the revival of Tibetan Buddhism. Mongols celebrated the rediscovery of Chinggis Khan as a national symbol through religious celebrations, national festivals, academic conferences, poetic renditions, art exhibitions, and rock songs.3 His name and image were also commodified. The international airport at Ulaanbaatar is named after Chinggis, as are one of the capital’s fanciest hotels and one of its most popular beers. Chinggis’ image appears on every denomination of the Mongolian currency.

This revival of a national cult, one that had been banned during the socialist era, is a response to endemic corruption, growing economic inequalities, and a host of other social and environmental problems arising from the abrupt transition to the market economy after 1990. State promotion of the Chinggis cult and Mongolian unity deflect widespread hostility against the small, wealthy elite and corrupt politicians. Ordinary Mongolians are presented with the promise of a better future through memories of a glorious past.4

As globalization greatly increased Mongolia’s cultural contact with the outside world, Mongolia’s deification of Chinggis coincided with and mutually reinforced a trend in the West reassessing the role of Chinggis Khan in world history. Some Western writers have heaped extravagant and highly dubious praise on Chinggis Khan, painting him “as an advocate of democracy, women’s rights, and international law on the basis of distorted and tortuous reading of the sources about him.”5

On the other hand, the majority of Mongolists in the West are generally far more balanced and grounded in their re-evaluation of Chinggis Khan and the Mongol Empire. While acknowledging the death and destruction wrought by the Mongols in their conquests, they also recognize the Mongols’ substantial contributions to the expansion of long-distance trade and cultural exchange, with lasting impact on cultural and technological diffusion. Historian Morris Rossabi condemns Chinggis Khan for the loss of life and devastation that resulted from his conquests and occupation. But he also lauds Chinggis Khan for his unification of the diverse Turco-Mongol peoples on the Mongolian steppe, his administrative and legal innovations, his fostering of trade expansion and knowledge circulation by supporting merchants and artisans, his interest in new technologies and recruitment of foreign experts, and his adoption of a policy of religious toleration.6

Mongolists and world historians today commonly see Chinggis Khan and the Mongols as forerunners of globalization. Historian Henry G. Schwarz observes: “Several key elements of globalization today, such as the relatively free movement of goods, extensive cultural interchange over large areas of the globe, and the creation of a written language to serve as the official form of communication, were part and parcel of the Mongol world empire as well. This fact reminds us that globalization is not a brand-new phenomenon in human history …”7 Similarly, Morris Rossabi labels the Mongol era as “the onset of the global age,”8 while Michal Biran sees it as a “period of early globalization.”9

This view of Chinggis Khan and the Mongols as globalizers dovetails with recent academic trends in global studies. While globalization remains a contested concept,10 scholars commonly agree that it is “a process that transforms economic, political, social, and cultural relationships across countries, regions, and continents by spreading them more broadly, making them more intense, and increasing their velocity.”11 Moreover, scholars have increasingly recognized globalization as “a long-term historical process that, over many centuries, have crossed distinct qualitative thresholds,”12 and as “a set of overlapping sequences (not stages)” with multiple regional origins13 and multiple dimensions, not just economic-technological but also political, cultural-ideological, and ecological.14 Fostering unprecedented levels and geographic spread of economic, technological, and cultural exchanges in Eurasia, the Mongol Empire thus marked “the first globalization episode.”15 Chinggis Khan “started the process … of creating the physical, commercial, and cultural connections that define globalization today.”16

Mongolians today welcome and embrace these revisionist perspectives as they provide a foundation for their construction of national identity.17 In honor of the 800th anniversary of Temüjin’s coronation as Chinggis Khan in 2006, Mongolia held year-long celebrations, with the unveiling of a 40-meter high statue of the khan near the capital of Ulaanbaatar, shortly before the climactic “three-day Nadaam festival, which features the traditional “three manly sports” of horse-racing, wrestling and archery.”18

|

Figure 1. Statue of Chinggis Khan, on the outskirts of Ulaanbaatar (Photo by author) |

This anniversary also caught the attention of the world beyond Mongolia. The focus of this paper is an analysis of three film productions that were released around that time: two international co-productions, Sergei Bodrov’s Mongol (2007) and Sawa Shinichirō’s The Blue Wolf: To the Ends of the Earth and Sea (2007),19 together with a domestic Chinese television series, Chengjisi Han (2004).20 I compare these productions to arrive at insights into the cultural and historical significance of Chinggis Khan in the age of globalization, to demonstrate how his story is variously interpreted through the lenses of individual filmmakers, national agendas for the construction of national identity and community, and the global cultural marketplace. All three film productions have high production values, attempt to humanize the world conqueror, and empower women by assigning them prominent, active and even heroic roles in their narratives. But they also reflect different agendas and visions that are in part a function of the national origins of their creators.

Each film production was shaped by the historical legacy and present relations between Mongolia and the creator’s country of origin: Soviet Union/Russia in the case of Mongol, Japan in the case of The Blue Wolf, and China in the case of Chengjisi Han. Moreover, each production’s reinterpretations or adaptations of key episodes in Chinggis Khan’s life provides important insights into their creators’ ideological conceptions. As Uradyn E. Bulag has argued, “Chinggis Khan has become the fantasy figure through which [Mongolia, China, Japan and Russia] perceives or defines itself as a meaningful entity.”21

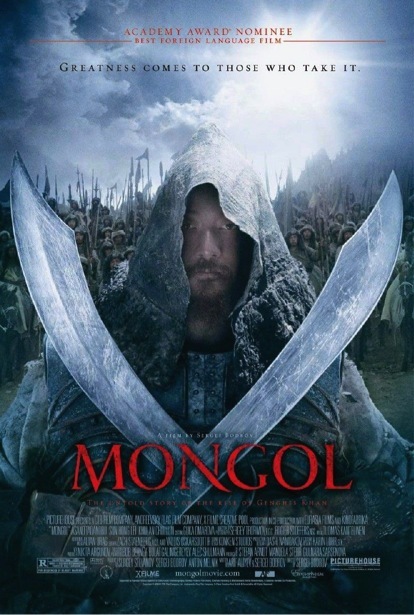

Bodrov’s Mongol

Mongol, directed and co-written by Russian filmmaker Sergei Bodrov, was a massive global project that involved multinational financing, casting in at least 8 countries, and a large international cast. 50% of the $20 million budget came from Russia, 30% from Kazakhstan, and 20% from Germany.

|

Figure 2. Mongol (directed by Sergei Bodrov, 2007). |

For the leading roles, Japanese actor Asano Tadanobu was cast as Temüjin, Chinese actor Sun Honglei as Temüjin’s blood brother and rival Jamukha, and Mongolian student Khulan Chuluun as Temüjin’s wife Börte. Shooting began in 2005 with a crew of 600, 40 translators, and thousands of extras and horses. It took place primarily in remote regions of China, Mongolia and Kazakhstan, ranging in terrain from snowfields to deserts to barren plains, and filming took 25 weeks over a two-year period. Besides the logistical difficulties, the challenge of cultural barriers and misunderstandings was immense.22

While Mongol was a monumental collective enterprise on the global scale, it was also principally the personal vision of Bodrov. Brought up in the Soviet Union, Bodrov became skeptical about the portrayal of Chinggis Khan as a monster in Soviet history textbooks. Russian and Soviet historians considered Russia under the Tatar Yoke of the Golden Horde to be a culturally and demographically calamitous era for the Russian people.23 However, after the Russian Revolution, a group of Russian exiles in Paris, collectively known as the Eurasianists, argued that “the motley geographic and ethnic composition of the dissolved Russian empire had fused Eastern Christian and steppe influences into a transcendent new synthesis.”24 They asserted that the Mongols/Tatars were not a negative and destructive force, but played a positive and leading role in the formation of the Russian state. Mongol protection prevented the incorporation of Russia into the West, which would have entailed the end of Orthodox Christianity, and Mongol ethnic and religious tolerance further helped to preserve the Russian language and religion.25 Muscovite Russia was the successor to the Mongol Empire rather than to Kievan Rus.26 “The most important Mongol contribution was not just the unification of Russia but making Russia the great descendant of the Mongol empire, which unified Slavic and non-Slavic people.”27

Virtually unknown in the Soviet Union, Eurasianism gained momentum in post-Soviet Russia in the 1990s through the popularization of the writings of Soviet cultural geographer and historian Lev Gumilev (1912-1992).28 Gumilev was even more sanguine about the historical role of the Mongols than his predecessors, the classical Eurasianists. He insisted that the traditional view of the Golden Horde as rapacious and uncivilized was dead wrong: there was no bloody conquest. Instead, the Russians voluntarily submitted to Mongol authority, and entered into a mutually beneficial and symbiotic partnership with the Mongols, without whose support the Russians might not have been able to resist being encroached upon by the Catholic West, and Russia itself not have been able to develop into a great power.29 Moreover, over time, the proto-Russian remnants of Kievan Rus fused with the Tatars (and also the Finno-Ugric groups) to form the new Great Russian ethnos, with the Tatars contributing in particular a fresh injection of dynamism and capacity for action.30 One key concept in Gumilev’s world historical view is passionarnost’ (passionarity), “signifying the instinct for self-sacrifice for a greater collective good,”31 a quality purportedly possessed by the nomadic raiders from the Eurasian steppes and by the Russians themselves as Eurasians.32 Gumilev also conceived passionarnost’ as a marker of heroic personalities throughout history as active, creative and transformative agents.33

Since his death, which coincided with the Soviet Union giving way to the Russian Federation, Gumilev “has become something of a scholar-saint,” with the brisk sales of his books,34 the assignment of his publications in the curricula of Russian universities and high schools, and the broad debates of his theses among Russian intellectuals.35 The ideas of Gumilev and post-Soviet neo-Eurasianists have gained wide currency among the Russian people, in particular, Vladimir Putin and his ruling circle. Among various competing ideologies for nation-building in post-Soviet Russia, “Eurasianism offered a renovated moral purpose … that was neither Marxist nor nationalist,” a Russian exceptionalism founded on “the millennia-old unity of inner Eurasia, and a lurking distrust of the West.”36 Gumilev’s sympathetic evaluation of the positive roles played by the steppe peoples in Russian history made Eurasianism attractive as a source of national identity formation to the Turkic-Mongolian peoples in the Russian Federation, as well as to Kazakhstan and Turkey.37

It was his reading of Gumilev’s writings that inspired Sergei Bodrov to search for the authentic Chinggis Khan, and to pursue it as a film project – one where Mongol was intended to be the first part of a trilogy on the life of Chinggis Khan.38 In interviews, Bodrov indicated that he is in agreement with the historical interpretations of Gumilev and the Eurasianists: Mongol protection helped preserve Russian religion and language; the intermingling of the Russians with the Mongols/Tatars “helped Russia develop positive ethnic characteristics”; the Mongols promoted commercial and cultural exchange. Most importantly, Bodrov believed that Chinggis Khan was “a tough but just leader who wished to create a just society. The image of a brutal savage is wrong.” He acknowledged that “Gumilev had provided the intellectual/historical framework for the movie.”39 An additional motivation for Bodrov was the fact that his grandmother was ethnically Buryat.40

In 2004, Bodrov began work on a screenplay with Arif Aliyev, his collaborator on his award-winning Prisoner of the Mountain. In addition to Gumilev’s The Black Legend, a collection of essays on the Mongols,41 Bodrov and Aliyev used The Secret History of the Mongols, a Mongol epic written sometime after Chinggis’ death in 1227,42 as a primary source.43 Despite Bodrov’s use of The Secret History as a reference point, he exercised considerable imagination and took liberties with its narrative in developing his screenplay. At the same time, he strived for cultural authenticity by using Mongolian in the dialogue, and by employing stuntmen from Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. He also sought to recreate the spiritual world of Mongol shamanism, or Tenggerism.

Bodrov simplified the story line and trimmed the cast of characters considerably. He omitted several key episodes in Temüjin’s life, for example, his killing of his half-brother Begter for snatching the fruits of his fishing and hunting.44 Among Temüjin’s five siblings, only his brother Khasar and his sister Temülen make brief appearances in Bodrov’s film. The complex rivalry among the various tribes and clans on the Mongol steppe, including the Merkits, Tatars, Kereyits and Naimans, is reduced to the conflict between Temüjin and Tarkhutai of the Tayichi’ut clan, between Temüjin and the Merkits, and between Temüjin and his blood brother Jamukha.

A key episode in Temüjin’s life that is greatly simplified in Bodrov’s version is the kidnapping of his wife Börte by the Merkits. In The Secret History, the seeds of this event dated back to the marriage of Temüjin’s parents, Yisügei and Hö’elün. Chiledu of the Merkit tribe was returning home with his new bride Hö’elün, when Yisügei, a leader of the Borjigin clan of the Mongol tribe, swooped in, and captured Hö’elün, subsequently taking her as his wife. Temüjin was born the eldest son of Yisügei and Hö’elün around 1162.45 Shortly after Temüjin and Börte’s marriage in 1179, the Merkits launched a surprise attack on their camp, resulting in Temüjin’s flight, and the capture of his wife and his father’s second wife. Börte was given to the Merkits as a wife for Chilger, the younger brother of Chiledu, Hö’elün’s first husband.46 With the help of Toghril Khan (also known as Ong Khan) of the Kereyit federation, and Jamukha of the Jadaran clan of the Mongols, Temüjin launched an attack on the camp of the Merkits, rescuing Börte. Börte gave birth to Jochi, Temüjin’s eldest son, shortly thereafter, but there was some doubt as to his actual paternity on account of the circumstances.47

Both Toghril and Jamukha played key roles in Temüjin’s life as anda, sworn blood brothers. Toghril had been the anda of Yisügei, who had helped him regain his leadership of the Kereyit federation. As for Jamukha, he and Temüjin swore the oath of anda no less than three times in their youth.

Toghril, however, is missing completely in Bodrov’s film version. Bodrov chooses to emphasize the anda relationship between Temüjin and Jamukha, so that he can highlight Temüjin’s passionarity as exemplified in his total loyalty and selfless dedication to his family and followers, in contrast to Jamukha’s lack thereof. In Mongol, after losing Börte to the Merkits, instead of seeking other women as substitutes, he goes to Jamukha for help. Jamukha is incredulous: “Mongols don’t make war over a woman.” He finally agrees, first because he is Temüjin’s anda, but even more because this war offers an opportunity for looting. However, in order to avoid alerting others to the connection between the expedition against the Merkits and the rescue of Börte, Jamukha insists on waiting until the next spring. He also enjoins Temüjin to refrain from letting other people know that they are going to war for Börte. The cold, calculating and swaggering Jamukha underestimates Temüjin for what he sees as softness. When Temüjin finally rescues Börte and finds her pregnant, he immediately accepts the unborn child as his son as he points to Börte’s belly and tells Jamukha: “This is my son.”

Unlike the cold-hearted Jamukha, Temüjin is unfailingly sensitive, empathetic, and unconditionally loyal towards his family and his followers. He commits himself to a risky attempt to rescue Börte while Jamukha would have simply taken another woman were his own wife kidnapped under similar circumstances. Temüjin includes the prohibition against killing women and children in his laws, after Börte asks him to spare the women and children who are routinely slaughtered by the victorious tribe in a military confrontation. He is liberal towards children of indeterminate paternity, never questioning whether Jochi is his son, and joyfully adopting Börte’s daughter with another man.

Temüjin’s fairness and magnanimity towards his followers contrast with Jamukha’s self-centered avarice. After the two anda have defeated the Merkits, Jamukha grabs the bulk of the spoils, but Temüjin takes only 1/10th of the remaining booty, and allows his men to divide the rest, a generosity that prompts two of Jamukha’s men to defect to his side. Subsequently, Temüjin’s reputation for fairness and generosity among his followers attracts more and more people to his leadership. As the two anda become the leading rivals for leadership of the Mongolian steppes, Temüjin’s passionarity prevails over Jamukha’s cold-hearted and instrumental rationality. While Jamukha sells Temüjin into slavery after a battlefield victory, Temüjin is merciful, sparing the life of Jamukha and releasing him, following the latter’s defeat and capture.48

Bodrov places considerable, even mystical emphasis on Temüjin having Tenggeri (Heaven-God) on his side as an important factor behind his success in overcoming inauspicious beginnings, forging and expanding his network of allies and band of followers (nököd), defeating all rival tribes and clans, and unifying the Mongolian steppe under his rule. Bodrov’s focus on religious mysticism reflects Gumilev’s historical views emphasizing passionarity over ideology and institutions.

The Mongolian belief in Tenggeri was a source of religious inspiration for the Mongol expansion in the 13th and 14th centuries. It was invoked by Temüjin to legitimate his empire at his coronation as Chinggis Khan in 1206, when he founded the Great Mongol State.49 Bodrov, however, does not dwell on the ideological and legitimizing aspects of Tenggerism. Instead, Bodrov emphasizes its mystical elements by treating Tenggeri as a benevolent and protective force.50

Figure 3. The Blue Wolf, the mythical progenitor of the Mongols used by Bodrov to represent Tenggeri, responds to Temüjin’s Prayer in Mongol (2007). |

Just as Tenggerism is stripped of its ideological and political dimensions, Bodrov presents a similarly simplified image of the yasa, “a set of rules and regulations about the military and the systems of governance and justice,” which historian Morris Rossabi considers to be Chinggis Khan’s “most significant administrative innovation.”51 In Bodrov’s reinvention, at the conclusion of another visit to the sacred mountain to seek help from Tenggeri, Temüjin formulates his yasa to keep the Mongols from fighting one another. He declares: “Our laws are simple. Don’t kill women and children. Don’t forget your debts. Fight enemies to the end. And never betray your khan.”

While Bodrov attempted to be culturally authentic, he also injected modern cultural sensibilities into his film. Bodrov’s version of Börte is a significantly more active figure than how she was described in The Secret History of the Mongols, and exhibits passionarity as much as her husband Temüjin through her self-sacrifice and devotion. First, she actively chooses Temüjin as her husband, announcing her decision to him instead of simply agreeing to an arranged marriage cementing the alliance of two lineages (kuda). Even more significantly, Börte heroically rescues Temüjin twice through self-sacrifice. When Temüjin is shot in the back by an arrow during the Merkit raid, Börte whips his horse so that it will run off with his wounded master, while she herself is captured. Later, Temüjin is imprisoned in the Tangut kingdom of Xia. Börte persuades a Uyghur merchant to allow her to join his troupe in order to reach the Tangut Kingdom, even at the cost of offering her body to him and giving birth to a daughter. After arriving in the kingdom, Börte manages to bribe and coerce the guards into giving up a key that allows Temüjin to escape.52

Given Gumilev’s conception of modern Russia as a fusion of Slavic and Mongol/Tatar peoples, and a successor to the Mongol Empire, Mongol can be viewed as a prequel to the narrative of the birth of the Russian nation. In his self-abnegation, Bodrov’s Temüjin has an abundance of passionarity that is characteristic of great world leaders, as also does his wife Börte. In Gumilev’s view of history, passionarity or the spirit of self-sacrifice exhibited by first a few, and then by a community, leads to the formation of an ethnos or a nation. So too in Bodrov’s Mongol, the passionarity of Temüjin and Börte presages the emergence of the Mongol nation and eventually the Russian nation.

The Blue Wolf

While Mongolians approve the glowing evaluations of Chinggis Khan by some Western writers,53 they are generally dismayed by foreign film productions of his life, particularly for their deviations from The Secret History of the Mongols, which they consider the most authentic account of Temüjin’s life. Despite Bodrov’s efforts at cultural authenticity and his Mongolian-language screenplay, Mongolians were upset by the casting of a Japanese actor as Temüjin and a Chinese actor as Jamukha, rather than Mongol actors. State Artist and film producer G. Jigjidsuren denounced Mongol “as an unacceptable distortion of Mongolian history and as a brutal assault on Mongolian sensibilities.”54

While The Blue Wolf was billed as a Japan-Mongolia co-production shot on location in Mongolia over a four-month period in 2006, Mongolians were no happier with it than they were with Bodrov’s Mongol. The Blue Wolf was the personal project of co-producer Kadokawa Haruki, a publisher and film director who had conceived of a movie project on Chinggis Khan 27 years before it finally came to fruition.

|

Figure 4. The Blue Wolf: From the End of the Earth and Sea (directed by Sawa Shinichirō, 2007). |

The film’s $30 million budget came entirely from Japanese sources. Moreover, the film featured Japanese actors and one Korean actor in the leading roles, as well as a Japanese-language script and soundtrack. There were 27,000 Mongolian extras and 5,000 Mongolian Army soldiers, along with local support staff, and they made up the main form of Mongolian participation.55 It is fair to say that The Blue Wolf is more representative of Japanese fascination with Chinggis Khan and of a Japanese re-imagining of his life story, than of a Mongol perspective.

|

Figure 5. Coronation of Chinggis Khan in 1206, as recreated in The Blue Wolf: To the Ends of the Land and Sea (2007). |

Japanese fascination with Mongolia is, in part, derivative of Japan’s fascination with its own “history” and image, as demonstrated in several enduring myths linking the Mongols and the Japanese that remain popular even now. Historian Junko Miyawaki-Okada observes that the Japanese public today associates the Mongols and Mongolia with three tales: (1) Japan was saved from the Mongol invasions of 1274 and 1281 by a Divine Wind (kamikaze);56 (2) the Japanese imperial family were descendants of horsemen from the Mongolian plateau who conquered Japan; and (3) Chinggis Khan was actually Minamoto no Yoshitsune, hero of the Gempei War. She further argues that these stories were products of Japan’s invention of tradition in its search for and construction of a national identity since the Meiji Restoration.57

If the Kamikaze Myth gives rise to the vision of Japan as a land uniquely blessed by the protection of the kami, the Horsemen Theory and the Yoshitsune myth link the Japanese and the Mongols not just by history, but also by blood. As anthropologist Uradyn E. Bulag asserts, such legends, along with the Altaic-Ural Thesis that came into vogue in late 19th Century Japan, are cultural products of Japan’s search for national identity, as well as of shifts in its historical-genealogical imagination since the Meiji Restoration, particularly around the question, “Is Japan a single-blood nation or a mixed-blood nation?”58

The legend of Yoshitsune escaping to Mongolia via Hokkaido and Sakhalin dated back to the Edo period.59 It spread widely in Japan after Suematsu Kencho’s 1879 thesis, written in English at Cambridge University, was translated into Japanese in 1885.60 Through Japanese translations and retelling, this myth maintains its hold on the popular Japanese imagination well into and beyond the 20th Century, sustaining public interest in Chinggis Khan and the Mongols.61

In the late 19th century, the mixed blood theory pertaining to the Japanese people’s origins triumphed over the single blood theory.62 As historian Prasenjit Duara has documented, late Meiji academics seized on the Ural-Altaic Thesis to develop “the notion of a Tungusic or pan-North Asian people, as a great Asiatic people constructed in the mirror image of the Indo-European people,” with Manchuria as their original homeland. In the early 20th Century, this thesis provided ethnographic support for the idea of a Japan-led alliance of the Tungusic peoples of East Asia, which included the Japanese, the Koreans, the Manchus, the Mongols, the Siberians and others, though notably excluding the Chinese. The Ural-Altaic Thesis was thus used to justify Japan’s colonization of continental Asia, specifically as a return of the Japanese people to their roots, as well as a fraternity of Asian peoples under the umbrella of Pan-Asianism and Japanese leadership.63

Similar to the Ural-Altaic Thesis, the Horsemen Theory, which emerged after Japan’s defeat in the Pacific War, emphasized the common racial origins of the Japanese and the Mongols: horsemen from the Mongolian plateau arrived on the Japanese archipelago via the Korean peninsula, conquered it, and established the imperial house of Japan. This account was widely welcomed by the Japanese at the time for lifting their spirits after a devastating defeat. By affirming the uniqueness of the Japanese imperial institution, the Horsemen Theory distanced the Japanese from the Chinese, and linked the Japanese to the Mongols who had been victorious over both China and Europe.64 Both the Ural-Altaic Thesis and the Horsemen Theory served as myths of national origins. While the former legitimized prewar Japanese imperialism, the latter provided psychological comfort after Japan’s defeat and devastation in the Pacific War.

The fascination of many Japanese with a notion of Japanese kinship with Mongols has created a durable market for cultural products related to Chinggis Khan and the Mongols. Japanese writer Inoue Yasushi, whose novel The Blue Wolf was one of the original sources for the film The Blue Wolf, stated that he first became fascinated with Chinggis Khan when, as a middle school student, he read Oyabe Zen’ichirō’s 1924 bestseller Chingisu Kan wa Minamoto no Yoshitsune nari (Chinggis Khan Was Minamoto no Yoshitsune).65 Eventually he decided to write a novel focusing “on the lone personality of Chinggis.”66 Inoue’s goal was “to depict the origins of his overwhelmingly—indeed, unfathomable—desire to conquer,” namely, compensation for his illegitimate birth origins,67 a theme that is taken up in the film The Blue Wolf (2007).

Inoue’s novel, along with another novel on Chinggis Khan by Morimura Seiichi, were the primary sources for the screenplay.68 The Blue Wolf focuses primarily on Chinggis Khan’s personal family relationships: those with his mother Hö’elün, his wife Börte, and especially his eldest son Jochi. The central conflict hinges on the question of paternity (brushed aside by Bodrov), specifically the paternity of both Temüjin and his son Jochi. The prominence of the theme of paternity, derived from Inoue’s novel, is a metaphor for the Japanese debate over whether Japan is a single-blood nation or a mixed blood nation.

The question of Temüjin’s legitimacy is raised in a number of situations. Most crucially, the film follows novelist Inoue’s version of the episode when Temüjin kills his half-brother Begter. Temüjin is driven to fratricide because Begter impugns him as a Merkit bastard and therefore not fit to head the family.69 In The Blue Wolf, Temüjin is plagued with doubt when he rescues Börte from the Merkits and finds her pregnant. Not only does he reject Börte initially, but later, when Jochi is born, he even tries to kill the baby until his mother Hö’elün stops him.70 Much of the subsequent plot line revolves around Temüjin’s persistent doubts and wavering acceptance of Jochi as his son, as well as Jochi’s feelings of hurt and rejection. In a climactic scene where The Blue Wolf deviates substantially from recorded history, Temüjin is angry over what he sees as Jochi’s apparent insubordination, as the latter had pleaded illness and failed to join his expedition against the Jin Empire. He suspects Jochi of rebellion. When he goes to Jochi’s camp, he discovers that Jochi has been wounded by a poisoned arrow and has lost his sight. After father and son reconcile, Jochi dies. Upon embarking on his expedition, Temüjin uses Jochi’s finger guard to fire off the first arrow in the direction of a Jin fortress.71 In the end, Temüjin overcomes his doubts over his own paternity and Jochi’s. Both Temüjin and Jochi are true descendants of the Blue Wolf in spirit and exemplify the virtues of Mongolian culture, regardless of their paternity. Similarly, whether Japan is a single-blood nation or a mixed blood nation is immaterial as long as its people embody the Japanese national spirit.

Just as Börte is portrayed as a heroic figure in Mongol, Khulan, one of Chinggis’ actual concubines, is reinvented in The Blue Wolf as a woman warrior who, after Temüjin defeats her in combat, chooses death over suffering the shame of rape. Temüjin, impressed with her courage, recruits her as one of his warriors to ride beside him into battle. Khulan eventually gives herself to Temüjin voluntarily. Just as Börte in Mongol saves Temüjin twice, so too does Khulan in The Blue Wolf, first by killing a would-be assassin and then by sucking poison from an arrow wound inflicted upon Temüjin. As with Bodrov’s treatment of Börte in Mongol, the framing of Khulan’s narrative in The Blue Wolf puts an emphasis on female agency, and humanizes the figure of the conqueror.

|

Fig. 6. Chinggis Khan and Khulan ride together into battle in The Blue Wolf: From the End of the Earth and Sea (2007). |

Unlike Mongol but similar to Chengjisi Han (discussed below), the conclusion of The Blue Wolf echoes the thesis of many scholars that Chinggis Khan was a trailblazing globalizer creating a borderless world. As Chinggis Khan embarks on his expedition against the Jin, Khulan asks why he is continuing to wage war when the Mongols are united. Chinggis responds: “Where I go, I conquer, and borders disappear. With freedom of movement, trade flourishes. Cultures and customs are respected, and life is enriched.” “But when you make war, blood will flow,” counters Khulan. Chinggis answers: “Khulan, for blood to be shed no more, blood must first flow.” Just as trade and cultural exchange are said to promote global peace according to the proponents of globalization, the Mongol wars will pave the way to Pax Mongolica, an era of unimpeded cultural and commercial flows, as well as of religious tolerance – a view promoted by Mongolists, world historians, and the film productions The Blue Wolf and Chengjisi Han.

Chengjisi Han

Much like the Japanese debates over whether Japan is a single-blood or mixed-blood nation, the Chinese also debated whether China was a single-blood (consisting only of the Han), or mixed-blood (comprising many others) nation.72 The Republican revolutionaries originally conceived of their movement as the uprising of the Han against the Manchus, and China as a nation for the Han only. But they quickly realized that this posed a danger of separatism, as first Mongolia in December 1911, and then Tibet in February 1912 declared independence.73 Sun Yat-sen abandoned the slogan of driving away the barbarians, and proclaimed a new republic comprised of a union of the five nationalities (wuzu gonghe 五族共和): the Han, the Manchus, the Mongols, the Hui, and the Tibetans.74

Mongolia itself had become divided in 1911, with the Northern part of Mongolia or Outer Mongolia breaking away from China and maintaining an autonomous state for eight years under the Buddhist lama Bogd Khan,75 while the Southern part of Mongolia or Inner Mongolia remained under Chinese sovereignty.

|

Fig. 7. Map of the country of Mongolia and Inner Mongolia, autonomous region of the People’s Republic of China (The Economist). |

Chinese forces briefly regained control over Outer Mongolia in 1919,76 only to be ousted in 1921 by invading White Russian forces under the command of the “Mad Baron” Roman von Ungern-Sternberg. The 130-day bloody rule of Ungern-Sternberg ended with the incursion of the Red Russian troops, eventually leading to the establishment of a Communist Mongolian People’s Republic (MPR) and the first Soviet satellite in 1924.77

Inner Mongolia, on the other hand, became a realm of contestation between the Chinese and the Japanese, who promoted separatism among the Manchus and the Mongols.78 As we have seen, the Japanese legitimized their continental expansion with the ideological support of Pan-Asianism and the Ural-Altaic Thesis, essentially establishing a kinship with the Manchus, the Mongols, and other nationalities. As Japan posed an existential threat to China’s territorial integrity and even national survival, the KMT responded by re-working the vision of China as a Five Nationality Republic (wuzu gonghe) into one of a homogenous Chinese nation (Zhonghua minzu 中华民族), with non-Chinese peoples linked by blood to the Han through common ancestors.79 While the Japanese appropriated Chinggis Khan through claims of kinship with the Mongols, and even Chinggis as a Japanese hero, in order to establish a distinct Japanese identity and distance themselves from the Chinese, the Chinese Nationalists asserted that Chinggis Khan was among the greatest Chinese heroes, and that Khubilai Khan was the first anti-Japanese resistance fighter.80

The People’s Republic of China had recognized the Mongolian’s People’s Republic and established diplomatic relations days after its founding in 1949. In the 1950s, relations expanded rapidly as the Chinese provided substantial economic assistance and scores of Chinese construction workers.81 In 1956, Mao Zedong acknowledged to a Mongolian delegation that “Our ancestors had exploited you for three hundred years” and that therefore, “it was China’s duty to aid Mongolia.”82

With the outbreak of the Tibetan Rebellion and the flight of the Dalai Lama in 1959, the Chinese confronted a political need to cement national unity. In the field of history, the marital unions between Chinese princesses and court ladies, such as Princess Wencheng and Lady Wang Zhaojun, with Tibetan kings and other non-Chinese chiefs were emphasized as genealogical and cultural affiliations binding the Chinese and the ethnic minorities, such as Tibetans and Mongols, in the distant past. A re-evaluation of Chinggis Khan as a Chinese national hero became necessary.83

China’s re-assessment of Chinggis Khan’s role in history became an ideological issue in the Sino-Soviet split by the early 1960s. Throughout the Soviet period, the Russians consistently denounced Chinggis and the Mongols for two centuries of Russian national humiliation under the “Tatar-Mongol yoke.”84 Until 1959, the CCP did not go as far as either the KMT or the Japanese thinkers or writers to claim Chinggis Khan as one of their own. But during the War of Anti-Japanese Resistance, the Chinese Communists did valorize Chinggis Khan as a Mongol hero – an attempt to win over Mongols in both Inner Mongolia and the Mongolian People’s Republic.85 In the 1950s, the Chinese promoted the cult of Chinggis Khan in Inner Mongolia by returning his shrine from Gansu (where it was moved during the war for safekeeping) to Ordos, as well as by launching the construction of a three-domed mausoleum in 1954. The Chinese government sought to win the support of the Inner Mongolians, and simultaneously, to make the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region a model for the Mongolian People’s Republic, where Chinggis Khan was still deemed a feudal ruler and hence unworthy of being a role model for the nation.86

In 1962, the Mongolian People’s Republic (MPR) celebrated the 800th anniversary of the birth of Chinggis Khan, who was to be honored with a 36-foot monument, commemorative stamps, and speeches valorizing him as the founder of the Mongol nation. The Soviets, however, reacted by violently denouncing Chinggis as “a reactionary and evil figure,” forcing the cancellation of the celebrations and the dismissal of Tomor-Ochir, the second-ranking member of the Politburo of the Mongolian People’s Revolutionary Party, who was in charge of ideology and propaganda.87

Meanwhile, not only were the Chinese holding celebrations for the 800th anniversary of Chinggis Khan’s birth, much like the MPR were, but an article on Chinggis Khan, written by China’s leading Mongolist historian Han Rulin, also signified a fundamental re-evaluation of his role in history. Han argued against the total negation and denunciation of the khan. Instead, he should be eulogized as a national hero of China, specifically for unifying the country and removing the barriers to communication between East and West, thus making it possible for the transmission of Chinese civilization westward.88 The Soviets reacted by attacking the Chinese for nurturing a “Chinggis Khan personality cult” and whitewashing the bloody Mongol invasions of the West “as actions that contributed to ‘mutual exchange of culture between East and West.’”89 They accused the Chinese of imperialist ambitions and encroachments on Mongolia, and cited Chinese praise for “a paragon of evil” as evidence of the perfidiousness of Chinese leadership. The Chinese, for their part, accused the Soviets of colonizing Mongolia and other countries, and presented Chinggis Khan as the symbol and hero of the oppressed yellow race.90

The onset of the Cultural Revolution in 1966 led to an abrupt reversal of the Chinese evaluation of Chinggis Khan and Chinese policy toward Inner Mongolia. As Inner Mongolians’ loyalty to China came under suspicion, the Chinese denounced Chinggis Khan as “a brutal feudal conqueror” and a “nationalist.” Similarly, China’s highest-ranking minority nationality official, the Mongolian Communist Ulanhu, was dismissed as leader of Inner Mongolia, and denounced as “Chinggis Khan the Second.” Mongol cultural heritage came under brutal assault, and the Mausoleum at Ordos was ransacked in 1966. The Cultural Revolution brought about the deaths of 20,000 Inner Mongolians.91

The end of the Cultural Revolution, together with the beginning of reform and opening in the 1980s, brought yet another drastic turn in China’s policy towards national minorities, now conceived as constituents of the “Chinese nation” (zhonghua minzu) along with the Han. Chinese academics and officials reconceptualized the “Chinese nation,” which had originated with Chiang Kai-shek and the KMT’s assimilationist vision, and promoted the idea of the “multicultural unity of the Chinese nation” (zhonghua minzu duoyuan yiti).92

During both the Republican period (1912-1949) and the Maoist era (1949-1976), the dominant Chinese historical narrative had emphasized heroic Han resistance against barbarian invasions. In contrast, the official interpretation of Chinese history since the 1980s treats ethnic minorities within China’s current boundaries as having always been a part of the Chinese nation. The national minorities came to be seen as having made positive contributions to China’s cultural and political development, and their military conflicts with the Han nationality came to be interpreted as civil conflicts between nationalities in China. Conquering dynasties, including those of the Mongols and the Manchus, hitherto regarded as “foreign,” are now considered “Chinese,” furthering efforts for national unification and territorial expansion. The Yuan Dynasty, in particular, made a substantial contribution to national unity by its inclusion of Tibetans, Uyghurs and Muslims in a reunified China, while Chinggis Khan came to occupy a central place in Chinese history both as the unifier of China, and as “the only Chinese who ever defeated Europeans.”93

This narrative of the “multicultural unity of the Chinese nation” serves the political needs of the People’s Republic of China for the integration of ethnic minorities within its borders.94 In particular, Chinese co-optation of the image of Chinggis Khan seeks to defuse the dangers of pan-Mongolism. Long dormant due to Soviet suppression in the Socialist era, Mongolian nationalism in Mongolia has surged since 1990, following the end of Soviet domination. In that year, the Mongolian Democratic Party put forth its slogan of “Uniting the Three Mongolias” (Mongolia, Inner Mongolia, and Mongolian Buryatskaya), with the long-term goal of uniting Mongols in these three regions, as well as those in Xinjiang and elsewhere, under one “Great Mongolia.” The Chinese government remained highly concerned about pan-Mongolism, which had historically incited political demands and the mobilization of Mongols in Inner Mongolia. There was perceived danger to China’s national integrity and security, posed by independence movements in Inner Mongolia, as well as in Xinjiang and Tibet.95

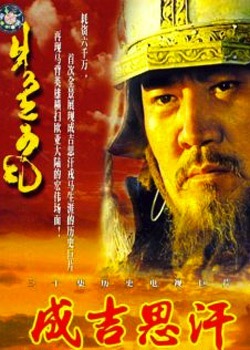

Although conceived as mass entertainment for a domestic Chinese audience, the Chinese television production of Chengjisi Han also serves state goals of promoting ethnic integration and national territorial integrity, largely by adhering closely to the current official conception of China as a multi-ethnic state.

While the production of Mongol was delayed by logistical and cross-cultural communication issues, the domestic release of Chengjisi Han was held up by political concerns and censorship. Historian Zhu Yaoting, who wrote a detailed biography of Chinggis Khan in 1990,96 also wrote the script for Chengjisi Han. The series was completed in 2000, and first screened in Taiwan in 2001, and Hong Kong in 2002. However, China Central Television (CCTV) did not broadcast it on Mainland China until 2004. According to Zhu Yaoting, this long delay was due to a lengthy process of reviews by various government agencies, including the United Front Department and the State Ethnic Affairs Commission, followed by numerous rewrites in response to the concerns raised. Some people worried that the series would be regarded as glorifying military aggression and foreign conquests, subsequently fanning international fears of a Chinese threat.97 As The Economist puts it, “The Chinese government worries that recalling such episodes [as the Mongols’ Western expedition and slaughter of Muslims] might reinforce Western fears of a resurgent China and its military potential and undermine its cosy relations with the Islamic world … The censors insisted on substantial cuts to avoid references to conquered regions with which modern countries might associate themselves.”98 Zhu Yaoting also mentioned that other bureaucrats feared that the series might trigger ethnic tensions and religious conflicts within China, and that there were also differences of opinion over the historical evaluation of Chinggis Khan.99

Out of the three productions discussed thus far, Chengjisi Han’s account was the closest to the events recorded in The Secret History of the Mongols and other historical sources. Unlike Mongol and The Blue Wolf, it featured mainly ethnic Mongols in the leading roles, even if they spoke Mandarin Chinese as opposed to Mongolian. Ba Sen, a Mongolian actor who is descended from Temüjin’s second son Chaghadai,100 played the lead role of Temüjin.101 Filmed in Inner Mongolia, the series mobilized thousands of extras from the People’s Liberation Army and the People’s Armed Police in its mass scenes.

|

Figure 8. Chengjisi Han (directed by Wang Wenjie, 2004) |

Unlike the negative reception of Mongol and The Blue Wolf in Mongolia, an uncut version of Chengjisi Han dubbed in the Mongolian language received an enthusiastic response from audiences in 2006.102 The fidelity of Chengjisi Han to The Secret History of the Mongols, together with its use of ethnic Mongols in its leading roles, were undoubtedly strong selling points for the citizens of Mongolia. However, one suspects that the dubbed version for Mongolia might have edited out or altered the dialogues and the voiceover commentary in the Chinese language version that identify Chinggis Khan as a Chinese national hero, as discussed below. Such historical revisionism would have outraged the Mongolians.

The television series supports China’s current narrative of the Mongols as part of the Chinese family, specifically by framing Temüjin’s story to emphasize: (1) the links between the Mongols and the Central Plains of North China before and during his lifetime; and (2) the key roles of his Chinese and Sinicized non-Chinese advisors in inculcating him with the values of Chinese civilization. Temüjin’s historical contributions to the unity of China are explicitly stated by these advisors or in the narrator’s commentary that concludes each episode.

Despite the fact that Temüjin will not step on the soil of the North China plain for many years to come, in 1171, at the age of 9, his father Yisügei teaches him about the great heroes of the Jurchen and the Song: the Jurchen leader Aguda – who liberated his people from oppression under the Khitans and founded the Jin Dynasty – Yue Fei, the Yang family generals, and other courageous Chinese generals who were undermined by the bad emperors and corrupt ministers of the Song Dynasty. The Jin is engaged in the great enterprise of eventually conquering the Southern Song and simultaneously dominating the Mongolian grasslands, Yisügei tells Temüjin, in whose mind is thus seeded the idea of unifying China Proper with the steppes of Inner Asia (Episode 2).

After Yisügei arranges for Temüjin’s engagement to Börte, Börte introduces Temüjin to the cultural splendor of the Central Plains, not simply the consumer goods, such as beds and quilts that her tribe acquired through trade, but more importantly, the value of books and learning. When Temüjin scoffs at the collection of books in Chinese, Khitan, and Jurchen that his future in-laws possess, Börte tells him that she has learned some Jurchen script, and that books constitute the source of wisdom. Moreover, the Jin is so rich in food and handicraft production that there is no need for the people to engage in herding. Here again the seeds of Temüjin’s future, of learning from the scholars of China and appreciating the value of an agrarian economy, are planted (episode 2).

|

Figure 9. Börte educating Temüjin about the values of Chinese culture in Chengjisi Han (2004). |

By privileging farmers and artisans over herders, Börte is also effectively entering into a long-standing debate over how to develop the economy of Inner Mongolia. Since the Qing Dynasty opened Inner Mongolia to Chinese migrant farmers in 1902, Inner Mongols had been aggrieved by the Chinese encroaching on their pastoral land, as well as by a growing Han population that turned the Mongols into a minority in their own home region.103 The Communist state promoted land reclamation, taking the position that the Mongols could advance economically and socially only if they adopted Chinese agriculture.104 “Organized and free Han migration and the cultivation of pastureland in Inner Mongolia have taken place at a heavy cost to Mongolian herdsmen.”105 Against the trends, Inner Mongols are fighting for the preservation of their pastoral lands and the Mongolian language as cultural markers for Mongol identity.106 Moreover, the Inner Mongols hew to Chinggis Khan “as a symbol of ethnic/cultural survival of their group in relation to the overwhelmingly dominant Chinese state and society,”107 even as Chinggis Khan has been appropriated as a Chinese national hero, and the Chinese government has claimed that its sponsorship of the Chinggis Khan cult constitutes proof of its “concern and love” for the great Menggu minzu or Mongol nationality.108

In this context, the production of Chengjisi Han may serve a similar function as the sponsorship of the Chinggis Khan cult from the perspective of the Chinese state. The TV series establishes at the outset multiple connections between the nomadic peoples of the steppes and the sedentary peoples of China: the enmity between the Mongols, the Jurchen and their grasslands allies such as the Tatars, the commercial connections between the steppes and the central plains, and, most importantly, the attractions of Chinese culture, and the importance of learning that a future world conqueror will need to honor it, so as to maintain and expand his empire.

Later episodes of Chengjisi Han emphasize the contributions of Yelü Chucai (耶律楚材), the Sinicized Khitan who becomes Temüjin’s most trusted adviser, and Changchun (長春), the Daoist sage.109 These men imbue in Temüjin an appreciation for the value of learning and scholarship for administering an empire, with particular attention to the three great teachings of China: Confucianism, Buddhism, and Daoism.

|

Figure 10. Yelü Chucai advising Chinggis Khan in Chengjisi Han (2004). |

The cultural absorption of the Mongols by the Chinese is indicated not only by the temptations of Chinese material goods, the value of Chinese learning, and the role of Chinggis Khan as the putative unifier of China after centuries of division, but also by the sanitization of the story line that may reflect concessions to Chinese cultural sensibilities and the desire to present Yisügei and Temüjin in as favorable a light as possible by Han standards. On the steppes of Mongolia in the 11th century, there were two routes for a man to find a wife: presenting gifts and performing a period of bride-service for his fiancée’s parents, or kidnapping a woman.110 From historical accounts, Yisügei took the second option. In Chengjisi Han, however, it is the Tatars who disguise themselves as Yisügei and his retinue in an attempt to kidnap Börte, so as to sow discord between the Borjigin clan and the Merkits. Moreover, Börte’s husband Chiledu runs away instead of standing his ground to fight, leaving Börte at their mercy. Yisügei comes onto the scene and rescues Börte, who is disgusted with Chiledu’s cowardice and gives herself to Yisügei (episode 1).

A second example of the story’s sanitization is Temüjin’s killing of his half-brother Begter. According to The Secret History of the Mongols, Temüjin and Khasar ambushed and killed Begter. In the television series, however, Temüjin does not ambush Begter. Instead, he offers a shootout to settle the dispute and allows Begter to shoot first. When Begter misses, Temüjin then shoots and kills him (episode 3).

A third instance of sanitization occurs in the Merkits’ kidnapping of Börte. According to The Secret History of the Mongols, the time between Börte’s capture and her rescue, after which Börte gave birth to Jochi, raised doubts among the Mongols about the legitimacy of Jochi as Temüjin’s son. Chengjisi Han, however, offers a rather different version. Börte is shown with morning sickness before her capture, while Chilegu is portrayed as a timid man who is kept out of Börte’s tent by her imperious rejection. Although he finally yields to his vices and rapes Börte in her sleep, he is cursed and whipped by Börte’s female servant (episode 5). When Börte is finally rescued and found pregnant, prompting Temüjin’s suspicion, Temüjin is scolded by his mother Hö’elün, who informs him that Börte was already pregnant before her capture, and that Temüjin is the one who should apologize for failing to protect his wife (episode 6).

While the narrative of Chengjisi Han reflects the cultural absorption of the Mongols, it also engages in the exoticization of the Mongols and their culture: interspersed throughout the series are interludes of song-and-dance sequences, with lyrics sung in Mongolian. Similar to the Japanese fascination with Mongolia, the Chinese are also attracted to the “otherness” of ethnic minorities, including the Mongols.111

What then is Chinggis’s historical role, according to Chengjisi han? The Daoist adept Changchun, who refused overtures from the rulers of the Jin and the Song, and initially rebuffed Chinggis’ summons, eventually agrees to meet the great Khan. Changchun observes: “Chinggis Khan is the only emperor on horseback of our times who can unite China. Since he has indicated in his summons his intention to devote himself to the people, I am willing to meet this Chinggis Khan” (episode 26). At the end of episode 29, the narrator points out: “The 13th century was a century of turbulence, a century of incessant warfare, and a century when China, which had been disunited for over four centuries, would be reunited for the fourth time, and also a century when China would have its closed doors broken down and be thrust onto the world stage of history. This was the achievement of the world-renowned hero of Mongol nationality (蒙古族) and the Chinese nation (中华民族) — Chinggis Khan!”

Echoing historian Han Rulin’s 1962 article and the current official historical narrative, Chengjisi Han argues that the great achievement of Chinggis Khan was more than reunifying China; he also set China on the path of globalization!

Conclusion

Chinggis Khan is much more than the founder of a world empire and the contemporary symbol of the Mongol people and Mongol nation. His image as a barbaric conqueror has been rehabilitated by Western scholars and authors, who have seen him as a pioneer of economic and cultural globalization, as an advocate of religious toleration, and, more controversially, as a promoter of modern values such as democracy and the rule of law. His story has been dramatized in the international mass media for the consumer market, as exemplified by the three films/television series analyzed in this article.

Mongol, The Blue Wolf and Chengjisi Han each humanizes the great conqueror, and the latter two agree with the contemporary reassessment of Chinggis Khan as a trailblazer who advanced global integration. Each production is shaped by the forces of globalization, the complicated past and present relations between Mongolia and the creator’s country of origin, and the appropriation of the image of the Mongol conqueror for national identity construction and commercial profit. The narratives of all three productions deviate from historical records, particularly with regard to modern sensibilities and differing views on the place of Chinggis Khan and the Mongols in the Russian, Japanese, and Chinese imagination. The historical agency of women features prominently in all three productions, particularly in Mongol, which invents two episodes of Börte saving Temüjin, and The Blue Wolf, which transforms Khulan from a concubine into a woman warrior. Sergei Bodrov’s emphasis on the mystical qualities of Tenggerism in Mongol derives from the Eurasianists’ view of Russian culture as a “transcendent new syntheses” of Orthodox Christianity and Mongol/Tatar culture. The Blue Wolf’s focus on the issue of Jochi’s paternity reflects the historical debate between single-blood and mixed-blood theories surrounding the origins of the Japanese people, as well as the feelings of affinity between the Japanese and the Mongols.112 In support of China’s official narrative as a “unified multi-national state,” Chengjisi Han accentuates Chinggis Khan as a national hero of China, one who reunified the country after centuries of division and set China on the road to globalization.

Notes

Morris Rossabi, “Modern Mongolia and Chinggis Khan,” Georgetown Journal of Asian Affairs 3, no. 2 (Spring 2017): 25.

Under Soviet direction, the Mongolian People’s Revolutionary Party (MPRP) killed many nobles, particularly those claiming descent from the Chinggisid line. Family and clan names were prohibited, in order to eliminate a source of national consciousness based on the Chinggisid descent. Hundreds of monasteries were destroyed, and 18,000 Buddhist lamas, along with 18,000 Buryats and other intellectuals, were executed. Henry G. Schwarz, “Preface,” in Mongolian Culture and Society in the Age of Globalization, ed. Henry G. Schwarz, Studies on East Asia, v. 26 (Bellingham, Wash: Center for East Asian Studies, Western Washington University, 2006), 4–6; Alicia J. Campi, “Globalization, Mongolian Identity, and Chinggis Khan,” in Mongolian Culture and Society in the Age of Globalization, ed. Henry G. Schwarz, 71–72; Johan Elverskog, “Theorizing Violence in Mongolia,” Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review, no. 16 (September 2015): 166.

When family names were restored under presidential decree in 1991, over 60% of the people chose Borjigid, the name of the clan of Chinggis. Campi, “Globalization, Mongolian Identity, and Chinggis Khan,” 75–78.

However, Rossabi suggests that Chinggis’ image in Mongolia is losing power as the Mongolian public is increasingly disillusioned by bleak economic prospects and political realities. Rossabi, “Modern Mongolia and Chinggis Khan,” 28–29.

Morris Rossabi, “Genghis Khan,” in Genghis Khan and the Mongol Empire, ed. William W. Fitzhugh, Morris Rossabi, and William Honeychurch (Arctic Studies Center, Smithsonian Institution and Mongolian Preservation Foundation, 2013), 105–9.

Morris Rossabi, The Mongols: A Very Short Introduction, Very Short Introductions (Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 2012), 60.

Michal Biran, “The Mongol Empire in World History: The State of the Field,” History Compass 11, no. 11 (November 1, 2013): 1021.

Manfred B. Steger, Globalization: A Very Short Introduction, Second edition, Very Short Introductions (Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 8–16.

A. G. Hopkins, “The History of Globalization—and the Globalization of History?,” in Globalization in World History, ed. A. G. Hopkins (New York: Norton, 2002), 19.

Manfred B. Steger, “Imperial Globalism, Democracy, and the ‘Political Turn,’” Political Theory 34, no. 3 (June 2006): 372.

A. G. Hopkins, “The Historiography of Globalization and the Globalization of Regionalism,” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 53, no. 1/2 (2010): 26.

Steger, “Imperial Globalism, Democracy, and the ‘Political Turn,’” 372; Steger, Globalization, chapter 3 to 7.

Ronald Findlay and Mats Lundahl, “The First Globalization Episode: The Creation of the Mongol Empire, or the Economics of Chinggis Khan,” in Asia and Europe in Globalization: Continents, Regions and Nations, ed. Göran Therborn and Habibul Haque Khondker, Social Sciences in Asia, v. 8 (Leiden; Boston: Brill, 2006), 13–54.

Jeffrey E. Garten, From Silk to Silicon: The Story of Globalization through Ten Extraordinary Lives, First edition (New York, NY: Harper, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers, 2016), 8.

As part of the national celebration of Chinggis Khan’s 850th birthday in 2012, Mongolia held an international conference on “Chinggis Khan and Globalization.” Biran, “The Mongol Empire in World History,” 1021.

The government also released 700 prisoners, or 10% of Mongolia’s incarcerated population. “Mongolians Honour Genghis Khan,” July 11, 2006.

This film was released in the West as Genghis Khan: To the Ends of the Earth and Sea. To avoid confusion, we refer to it by its Japanese title, The Blue Wolf: To the Ends of the Earth and Sea.

The English title for the DVD version of this television series is Genghis Khan. To avoid confusion, we refer to it by its transliterated Chinese title, Chengjisi Han.

Uradyn Bulag, Collaborative Nationalism: The Politics of Friendship on China’s Mongolian Frontier (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2010), 23.

Morris Rossabi, “Genghis Khan: World Conqueror? Introduction to Paul Ratchnevsky’s Genghis Khan: His Life and Legacy” (Blackwell Publishing), xvi– xvii, accessed April 2, 2010; Ryszard Paradowski, “The Eurasian Idea and Leo Gumilëv’s Scientific Ideology,” trans. Liliana Wysocka and Douglas Morren, Canadian Slavonic Papers / Revue Canadienne Des Slavistes 41, no. 1 (March 1999): 22. For a balanced and concise history of the Golden Horde, see Daniel C. Waugh, “The Golden Horde and Russia,” in Genghis Khan and the Mongol Empire, ed. William W. Fitzhugh, Morris Rossabi, and William Honeychurch (Arctic Studies Center, Smithsonian Institution and Mongolian Preservation Foundation, 2013), 173–79.

Stephen Kotkin, “Mongol Commonwealth?: Exchange and Governance across the Post-Mongol Space,” Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History 8, no. 3 (Summer 2007): 493.

Dmitry Shlapentokh, “The Image of Genghis Khan and Ethnic Identities in Post-Soviet Russia,” Asia Europe Journal 7, no. 3–4 (December 2009): 493.

Gumilev was the son of famed poets Nikolai Gumilev and Anna Akhmatova, and also a Gulag survivor. The third book in his trilogy on the history of the steppe nomads, which devoted considerable time to the rise of the Mongols and which Gumilev dedicated “to the fraternal Mongol people,” has been translated into English: L. N. Gumilev, Searches for an Imaginary Kingdom: The Legend of the Kingdom of Prester John, trans. R. E. F. Smith, Past and Present Publications (Cambridge [Cambridgeshire]; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1987). Gumilev’s grand synthesis of human history and natural history is also available in an English translation: L. N. Gumilev, Ethnogenesis and the Biosphere (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1990).

Mark Bassin, “Russian Eurasianism: An Ideology of Empire (Book Review),” Slavic Review 68, no. 4 (Winter 2009): 1016.

Andreas Umland, “Post-Soviet Neo-Eurasianism, the Putin System, and the Contemporary European Extreme Right,” Perspectives on Politics 15, no. 02 (June 2017): 468.

Nathans, “The Real Power of Putin.” At Lev Gumilev University in Astana, Kazakhstan, President Vladimir Putin declared in 2004 that “Russia is the very center of Eurasia,” and that Gumilev’s ideas of “a united Eurasia in opposition to the transatlantic West — were beginning to move the masses.” Kotkin, “Mongol Commonwealth?,” 495. In his December 2012 address to the federal assembly, Putin invoked Gumilev’s concept of passionarnost’ (passionarity) to promote “chest-thumping nationalism, the martial virtues of sacrifice, discipline, loyalty and valour.” Clover, “Lev Gumilev.”

Gumilev’s conception of Russia as a super-ethnos made him popular in Russia, but since he also “celebrated the Mongol and Turkic ethnoses,” he is popular in Inner Asia as well. Kazakhstan President Nursultan Nazarbaev invoked Eurasianism to position his country as a link between Asia and Europe. Kotkin, “Mongol Commonwealth?,” 495.

The future of Bodrov’s project remains uncertain. It appears that Bodrov’s plan has changed to making just a single sequel continuing the story to the death of Chinggis Khan in 1227. This sequel is tentatively titled Mongol II – The Legend, with a target completion date of 2019. “Mongol II – The Legend,” Getaway Pictures, August 5, 2016. It should be noted that Bodrov’s Mongol is by no means an isolated manifestation of Eurasianism in Russian popular culture. Bodrov had earlier made a film about Kazakhs in the 18th century, Nomad (2005). Even earlier in 1991, Nikita Mikhalkov directed Urga, about a Russian truck driver’s friendship with a Mongolian shepherd (Urga is the former name of Ulaanbaatar, the capital of Mongolia). In addition to Mongol, Karen Shakhnazarov’s Vanished Empire (2008) and Andrei Borisov’s By the Will of Genghis Khan (2009) are big budget productions that “invoke romanticized images of Russia’s East.” Bassin, The Gumilev Mystique, 240; Brian James Baer, “Go East, Young Man! Body Politics and the Asian Turn in Putin-Era Cinema,” The Russian Review, no. 74 (April 2015): 230.

Anton Dolin, “Sergei Bodrov: People Love to Pass the Blame onto Others,” Russia Beyond (blog), February 2, 2015. Buryats and Kalmyks are both Mongol subgroups, each with their republics in the USSR/Russia.

In numerous interviews, Bodrov refers to the title of Gumilev’s book as The Legend of the Black Arrow. But there is no such title in a bibliography of Gumilev’s publications. The closest title is The Black Legend, which is indeed a positive take on the Mongol era in Russia, and has been described as the “first book written in the western world to present Genghis Khan in a favorable light.” Brian James Baer, “Go East, Young Man! Body Politics and the Asian Turn in Putin-Era Cinema,” The Russian Review, no. 74 (April 2015): 238.

Three English translations of this Mongol epic are: Francis Cleaves, The Secret History of the Mongols (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard-Yenching Institute, 1982); Urgunge Onon, The Secret History of the Mongols: The Life and Times of Chinggis Khan (Richmond, Surrey: Curzon, 2001); Igor de Rachewiltz, The Secret History of the Mongols: A Mongolian Epic Chronicle of the Thirteenth Century (Leiden: Brill, 2006). The compiler of The Secret History is unknown, and its date is uncertain, as it stated only that it was completed in the year of the Rat, which had been variously advanced as 1228, 1240 or 1252. The date of 1228 is supported by de Rachewiltz, Ratchnevsky and Urgunge Onon, among others. Christopher Atwood, on the other hand, argues for the date of 1252 on the basis of his view of the text as “a unitary work, composed in a single style and full of partisan biases” rather than “the product of later additions, deletions and other editorial changes carried out during the Yuan and early Ming periods,” as Igor de Rachewiltz believed. Paul Ratchnevsky, Genghis Khan: His Life and Legacy, ed. and trans. Thomas Nivison Haining (Malden, Mass.: Blackwell, 2006), xiv; Ruth Dunnell, Chinggis Khan: World Conqueror (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Longman, 2010), xxiii; Christopher P. Atwood, “The Date of the ‘Secret History of the Mongols’ Reconsidered,” Journal of Song-Yuan Studies, no. 37 (2007): 40.

There are a number of other important primary sources on the Mongol Empire, including Ata-Malik Juvaini’s Tarikh-i jahangusha (History of the World Conqueror), Rashid al-din’s Jami‘ al-Tavarikh (Compendium of Chronicles), Yuanshi, the Chinese official history of the Yuan Dynasty, and travel accounts by scholars and religious officials, such as John of Plano Carpini, Friar Benedict the Pole, and William of Rubruck. However, The Secret History is the only primary source on the life of Chinggis Khan that was written by Mongols from a Mongol perspective, and therefore considered the most authentic account by Mongolians today.

William W. Fitzhugh, “Genghis Khan: Empire and Legacy,” in Genghis Khan and the Mongol Empire, ed. William W. Fitzhugh, Morris Rossabi, and William Honeychurch (Arctic Studies Center, Smithsonian Institution and Mongolian Preservation Foundation, 2013), 31–33.

This event occurred during a most difficult period for the preteen Temüjin, one where the Tatars poisoned his father Yisügei, and his Tayichi’ut clan kinsmen abandoned his family. The Secret History of the Mongols records that Temüjin and his brother Khasar were angered when their half-brothers Begter and Belgütei snatched first a fish, and then a bird that they had harvested, after which their mother Hö’elün simply told them to stop fighting among themselves. Temüjin and Khasar subsequently sneaked up on Begter and shot him to death with arrows, but Belgütei was spared. de Rachewiltz, The Secret History of the Mongols, 20–21.

The date of Temüjin’s birth remains a topic of some controversy. Several official Chinese sources date it in 1162, and this is the date accepted in Mongolia and in most secondary sources. However, the French scholar Paul Pelliot believed that 1167, given in one Chinese source, is the date most consistent with details of Chinggis Khan’s life recorded in other sources. If the account of Rashid al-Din were correct in stating that Chinggis Khan died at the age of 72, then he would have been born in 1155. Paul Ratchnevsky argued that 1155 is unlikely on the ground that it would imply that Temüjin only became a father at the age of 30 in a time when Mongols married early, and that he led a campaign against the Tanguts at age 72. Ratchnevsky believed that the exact year of Temüjin’s birth cannot be established, and that he was born in the mid-1160s. Ratchnevsky, Genghis Khan, 17–19.

Jamukha was in fact executed according to both The Secret History and Rashid al-Din, though the accounts vary in detail. Ratchnevsky, Genghis Khan, 87-88.

There is a controversy among scholars whether Chinggis merely saw himself as ordained by Tenggeri to rule over the Mongolian steppe, or whether he believed that Tenggeri sanctioned him to conquer the world, an interpretation that would be supported if the meaning of Chinggis was “ocean” and hence Chinggis Khan meant “universal ruler.” During the reigns of Chinggis’ successors from Ögedei to Möngke, Tenggerism developed into a sophisticated ideology “according to which all under Heaven must be united under the rule of the Mongols.” After Khubilai Khan conquered the Southern Song, thereby completing the establishment of the Mongol universal empire, he was more concerned with pacification and consolidation than with conquests. Though tolerant of and respectful to the major religions, Khubilai favored Buddhism as “a neutral and more universal religion in comparison with other religions known to him.” With the collaboration of the Tibetan lama ‘Phags-pa, Khubilai fused Buddhism with the Mongolian belief in Tenggeri to create a Tenggerism that legitimated his universal emperorship, by strengthening Tenggerism with the Buddhist model of the monarch as Chakravartin. Shagdaryn Bira, “The Mongolian Ideology of Tenggerism and Khubilai Khan,” in Mongolian Culture and Society in the Age of Globalization, ed. Henry G. Schwarz, Studies on East Asia, v. 26 (Bellingham, Wash: Center for East Asian Studies, Western Washington University, 2006), 13, 16–25.

In Mongol, when his nine-year old son Temüjin is frightened by thunder, Yisügei tells him: “Thunder means our god Tenggeri is angry. All Mongols are afraid of it.” When Yisügei is poisoned by the Merkits and lies dying, he tells his son: “Be strong, and ask our lord of the blue sky, Tenggeri, to help you.” When Temüjin as a boy is captured by Tarkhutai, chief of the Tayichi’ut clan and forced to wear a cangue, he runs to the sacred mountain and prays to Tenggeri. The blue wolf, who, according to Mongol myth, was the progenitor of the Mongols and is used by Bodrov to represent Tenggeri, appears, and he is miraculously released from the cangue (In The Secret History, Temüjin escaped with the help of Sorkhan Shira, a subordinate of the Tayichi’uts; de Rachewiltz, The Secret History of the Mongols, 22–26). In the climactic battle between the forces of Temüjin and Jamukha, lightning and thunder scare the Mongols. Temüjin, however, is fearless. Confident of protection by Tenggeri, he leads his troops forward and wins decisively.

Morris Rossabi, “Genghis Khan,” in Genghis Khan and the Mongol Empire, ed. William W. Fitzhugh, Morris Rossabi, and William Honeychurch (Arctic Studies Center, Smithsonian Institution and Mongolian Preservation Foundation, 2013), 105.

The Tangut Kingdom episode is completely invented by Bodrov, with no basis in The Secret History or any other historical sources, rooted only in Gumilev’s speculation about the possibility that Temüjin might have been a captive during a ten-year gap in existing records. Daniel Eagan, “Epic Challenge: Sergei Bodrov’s ‘Mongol’ Captures Tumultuous Life of Genghis Khan,” Film Journal International, 2008, 17.

B. Byambadorj, “Ch. Biligsaikhan: The Top Spots Should Be Taken, Not Begged For,” The UB Post, October 1, 2012.

Sorimachi Takashi played the role of Temüjin, while fellow Japanese actors Kikukawa Rei starred as Börte, Wakamura Mayumi as Hö’elün, and Matsuyama Ken’ichi as Jochi. Korean actress Ara played the pivotal role of Khulan, one of Temüjin’s concubines. Shochiku Co.’s official film site, first archived on Internet Archive on February 4, 2007.

For a succinct account of the invasions and recent archaeological finds, see James P. Delgardo, Randall J. Sasaki, and Kenzo Hayashida, “The Lost Fleet of Kublai Khan: Mongol Invasions of Japan,” in Genghis Khan and the Mongol Empire, ed. William W. Fitzhugh, Morris Rossabi, and William Honeychurch (Arctic Studies Center, Smithsonian Institution and Mongolian Preservation Foundation, 2013), 244–53. Interestingly, it was not until 1934 when the term kamikaze appeared in Japanese history textbooks. With the war turning increasingly against Japan towards the end of the Pacific War, the Japanese were hoping for a repeat of history: “Japan has never lost a war to outside enemies … it will be saved by a Divine Wind at the last moment … The Japanese expectation that the gods will somehow solve pressing difficulties remains alive even today.” Junko Miyawaki-Okada, “Homeland, Nationalism and the Legacy of Chinggis Khan: The Japanese Origin of the Chinggis Khan Legends,” Inner Asia. 8, no. 1 (2006): 126–27.

Contributing to the popularity of this book was Suematsu’s status as a son-in-law of Itō Hirobumi, Meiji Japan’s most eminent statesman. Suematsu later served as communications minister in 1898 and as minister of the interior in 1900-01. Bulag, Collaborative Nationalism, 40.

Miyawaki-Okada, “Homeland, Nationalism and the Legacy of Chinggis Khan: The Japanese Origin of the Chinggis Khan Legends,” 129–32. In the early 1940s, several English-language publications by Japanese authors reintroduced this myth to Western readers. Boyd, Japanese-Mongolian Relations, 1873-1945, 57.

Prasenjit Duara, Sovereignty and Authenticity: Manchukuo and the East Asian Modern (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2004), 183; Prasenjit Duara, “Ethnos (minzoku) and Ethnology (minzokushugi) in Manchukuo,” Asia Research Institute, Working Paper Series No. 74 (September 2006): 18-21. Accessed June 28, 2011.

The Occupation authorities had ordered that the Kojiki and the Nihon shoki be excluded from the school curriculum, allegedly for contributing to Japan’s militarism. The Horsemen Theory, which was seemingly buttressed by archaeological evidence, could replace those banned works as a new source of national myth and pride. The seminal work of the Horsemen Theory is the book by Japanese historian and archeologist Egami Namio, Kiba minzoku kokka: Nihon kodaishi e no apurōchi (1967). James Boyd, Japanese-Mongolian Relations, 1873-1945: Faith, Race and Strategy, Inner Asia Series, v. 8 (Folkestone: Global Oriental, 2011), 11; Miyawaki-Okada, “Homeland, Nationalism and the Legacy of Chinggis Khan: The Japanese Origin of the Chinggis Khan Legends,” 124-125.

Inoue Yasushi, The Blue Wolf: A Novel of the Life of Chinggis Khan, trans. Joshua Fogel (New York: Columbia University Press, 2008), 269. According to Yuki Konagaya, there are two prototypes for standard portraits of Chinggis Khan. The first was based on his famous portrait at the National Palace Museum in Taipei. The second prototype features Chinggis Khan with a very different costume, particularly his helmet. Oyabe, the author of Chinggis Khan was Minamoto Yoshitsune, had traveled to a Mongolian temple and found a version of the second prototype there. He identified the figure on Chinggis’ helmet as the family crest of the Minamoto clan, and concluded that Chinggis Khan was indeed Yoshitsune! Yuki Konagaya, “Modern Origins of Chinggis Khan Worship: The Mongolian Response to Japanese Influences,” in How Mongolia Matters: War, Law, and Society, ed. Morris Rossabi, Brill’s Inner Asian Library, volume 36 (Leiden; Boston: Brill, 2017), 151–52.

Inoue Yasushi, The Blue Wolf: A Novel of the Life of Chinggis Khan, trans. Joshua Fogel (New York: Columbia University Press, 2008), 270–72.

Inoue, 272; Konagaya, “Modern Origins of Chinggis Khan Worship: The Mongolian Response to Japanese Influences,” 155.

Morimura was also co-script writer. “Kadokawa’s next Big Thing – Genghis Khan and 3000 Real-Life Mongolian Cavalry,” Hoga Central, January 14, 2006.

This is in stark contrast to Bodrov’s Temüjin who accepts Börte’s pregnancy and later Jochi without question.