By the late 1880s, Salt Lake City had embarked on its rocky career as the eastern hub of Oceania. The Mormons had first landed in Hawai’i in the 1850s and, having failed among Euro-Americans, turned their attention to Native Hawaiians, learning their language, converting leaders and establishing plantation settlements enabled by new laws allowing foreign land ownership. For Natives, the faith aided the preservation of communal beliefs and practices in the context of rapid, dislocating change, including those brought by Mormon newcomers themselves. In the absence of a temple in the Pacific, Native converts began migrating to Utah, settling in the Warm Springs area of North Salt Lake City. The movement enacted the Mormon concept of “gathering,” but was also continuous with historically deep Hawaiian journeys of discovery, trade and labor that spanned the Pacific, including the Western edges of the imperial United States. Inscribed in Mormon imaginaries as Lamanites—descendants of Abraham who had traveled to the Americas and, after great wars, into the “west sea” in an “exceedingly large ship”—and gathered into a racially-stratified American West, the Hawaiian arrivals were socially and economically subordinated.

|

Iosepans photographed on Hawaiian Pioneer Day, circa 1914. This annual celebration, held on August 27th, commemorated the Hawaiians’ arrival to Iosepa with feasts, music and dancing. The events were attended by former missionaries, prominent church leaders and neighbors. |

In 1889, church leaders established a separate mission community for them in desolate, sun-scorched Skull Valley, seventy-five miles southeast of the city, where they worked for an abusive, church-owned agricultural company. They called the town—228 souls at its peak—Iosepa, Hawaiian for Joseph, after Joseph F. Smith, one of the first Mormon missionaries to the Islands. Most of the converts returned to Hawai’i after 1917, with the raising of an LDS temple there, and helped spread Mormonism throughout the Islands and the wider Pacific.1 Meanwhile, early Hawaiian settlement in Utah paved the way for Salt Lake City’s emergence, by the early 21st century, as the American city with the highest per capita concentration of Pacific Islanders outside of Honolulu, a metropolitan area simultaneously and inseparably in the American West and the Hawaiian East.

Mormon Hawaiian migrations, and the larger transits in which they are enmeshed, raise profound questions about how historians frame the Pacific, spatially, geographically, narratively, and epistemologically. As others have argued, the Pacific Ocean presents unique challenges and opportunities for those seeking to rethink history “beyond the nation,” as the world’s single largest physical feature, an immense water hemisphere containing over 25,000 islands, tremendous ecological diversity, and a staggering array of human adaptations, socio-political formations, and cultural interactions, collisions and crossings.2

The writing of “Pacific” history has a long lineage, but has emerged with heightened self-consciousness in recent years, fueled by journalistic and policy discourse surrounding “Pacific Rim” capitalism in general and the rise of China in particular, the aspirational model of the field of “Atlantic history,” and broader impulses towards transnational and global scholarship. As our conversations revealed, these histories spring from disparate origins, and approach the Pacific from within distinct intellectual traditions in terms of subject, method, politics, and conceptualization. The Pacific does different interpretive work in each of them. They unfold across different terraqueous spaces: rim and island, ocean and coast, North Pacific and South Pacific. There are histories of the Pacific, histories in the Pacific, and histories across the Pacific. Fernand Braudel’s compelling description of the Mediterranean as “a complex of seas” pertains equally well not only to the Pacific Ocean but to its historiographies: increasingly extensive, varying in depth, possessing imagined unities and uncertain edges.3

Precisely because an oceanic scope is often cast as a generative alternative to nationalized histories, it is worth emphasizing that that oceans—like nations, regions, continents, and localities—are historical constructions. Oceanic boundaries may be especially difficult to denaturalize because their foundational referent is a seemingly self-evident fact of “nature”; for this reason, oceans are susceptible to reification, even as other spatial categories are becoming more contingent. (In the Pacific case, a rhetorical stress on the “rim” may in part index a desire to bound a gargantuan phenomenon that by definition defies containment.) The South Pacific’s eastern border, for example, stretches along the meridian of Cape Horn, from Tierra del Fuego to Antarctica, according to the International Hydrographic Organization, but the Pacific Ocean, and the “adjacent” Atlantic, evidently do not respect this invisible line. And to what extent does “Southeast Asia,” enfolded in smaller seas, belong to Pacific history? The obvious point of a single, unbroken world ocean points to less obvious, but necessary cautions. Historians need to resist taken-for-granted definitions of the Pacific (which may fall back on problematic conventions); cultivate a self-awareness about their criteria for macro-geographic placement; and openoceanic histories out onto global histories, a task that environmental-historical approaches are currently in a unique position to undertake.4

What these varied Pacific histories share, to greater and lesser degrees, is their grappling with the enduring imprint of Euro-American and East Asian empire projects on modern historical imaginaries of the Pacific. As a function of European and later American and Japanese geopolitics, the Pacific was charted as an emptied space of possibility, a place of neglible or nullified human habitation where unwanted metropolitan settlers and industrial goods could be projected, sexual and racial constraints escaped, and historic destinies fulfilled. As a constitutive component of these oceanic frontier ideologies, Pacific Islanders were diminished: geographically isolated, temporally backward, historically static, politically fragmented, culturally heathen, and requiring the forces of rim-oriented capital, settlement, technology and culture to insert them into irresistible currents of evolutionary time.5

In what follows, I’ll identify three overlapping clusters of Pacific historical scholarship, identifiable by their subjects, concepts and politics: indigenist histories, critical empire histories, and connectionist histories. Of the three, indigenist histories wrestle most intimately and deliberately with the legacies of rim-centered, imperial knowledge production.

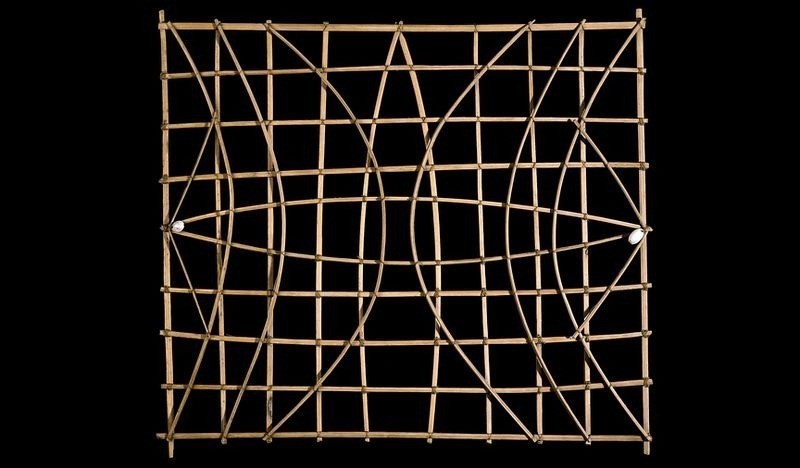

|

Stick charts like this one, showing wave patterns and currents, were used by Marshallese navigators to cross thousands of miles of Pacific Ocean. Indigenist historians have reconstructed complex Pacific Islander cultures and technologies of sea travel, countering racial-imperial narratives of Islander isolation and backwardness. |

This work seeks both to reconstruct the complexity and dynamism of Islander culture, politics and history and, implicitly and explicitly, to challenge and overturn the racist presumptions of colonizer history, past and present. Rather than being “discovered” by Europeans, Islanders were discoverers; far from “isolated” by the Pacific’s vast distances, they were its most adept navigators; rather than passive subjects and victims of Euro-American and East Asian power, they resisted outside impositions and, even where they failed to defeat them, shaped and bounded them. Much indigenist scholarship confidently defines itself in relation to the contemporary politics of sovereignty as they play out in questions of land and sea ownership, political autonomy and cultural pluralism. Scarcities of traditional, academic-historical primary sources and a sovereignty politics that extends to questions of historical epistemology has led some indigenist scholars to qualify or reject Western-derived notions of historical authority predicated on written texts and academic professional culture, and to uphold oral tradition and histories generated by and for Island peoples themselves.6 The risks here—romanticisms countering racist condescension; the minimizing of intra-Islander conflict; historiographic self-enclosure; usable pasts built to suit contemporary, post-colonial needs—have not prevented this field from posing trenchant, necessary challenges to Pacific history’s foundational trajectories.

A second historical enterprise can be usefully identified as critical empire histories. Emerging especially among historians of the US and Japan, and ethnic and cultural studies scholars from the 1990s forward, this scholarship contends with nation-centered frames and nationalist politics by foregrounding the central role of Pacific empire—colonial seizure, inter-imperial war, nuclear violence, military basing and tourist commodification, for example—to metropolitan state-building, social structures and nationalist ideologies.7 Taking nationalist blinders and apologetics as their targets, they have successfully shown Pacific empire to be a core component of modern, military-industrial state-building, in the US, Japan and Europe, while both undermining and historicizing imperial, exceptionalist claims of benevolence and self-defense. Their research has mapped empire-builders’ internal tensions, the contingencies of colonial and military projects on the ground, colonizers’ encounters with the worlds of Islanders, and the racialized and gendered ideologies that organized them. Methodologically, these works draw from colonial and post-colonial scholarship, and culturalized modes of diplomatic and military history, and bring to bear American, Japanese and European archival, linguistic, cultural and historiographic competences. While sympathetic to and aligned with Islander claims, this work is primarily oriented towards problematizing historical and ongoing expressions of nationalist and imperialist power originating elsewhere. Its occupational hazards include scholars’ unwitting narrative or analytical reproduction of colonizer tropes—into which they necessarily immerse themselves—and negligent or schematic attention to Islander histories, relative to the project of metropolitan critique.

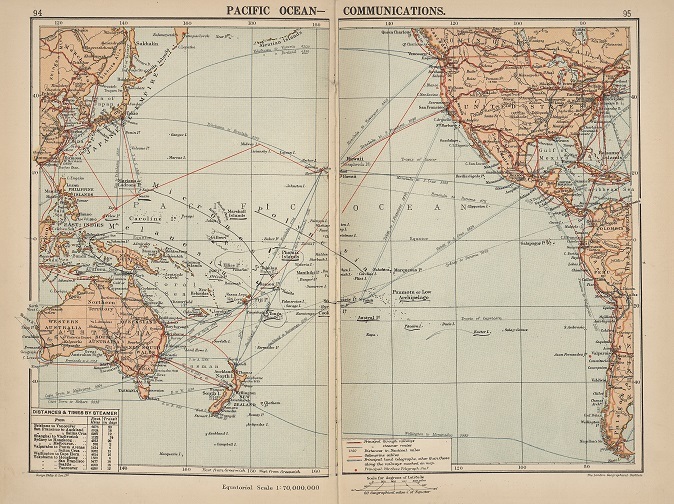

|

This commercial map produced in London in 1914 by Philips’ Chamber of Commerce emphasizes trans-oceanic connectivity, foregrounding railways, steamer routes (with distances and times), submarine cables, land telegraphs and wireless stations. |

A third mode of scholarship is what I’ll call connectionist: its primary object is to establish that histories previously thought to be separate were mutually imbricated. This work can be divided into two subsets. The first flies under the banner of global and transnational history. It hopes to bring global-historical techniques to Pacific history and vice versa, and to ultimately integrate the Pacific into global history’s narratives and analyses.8 On a smaller scale, it seeks to demonstrate that national states and subnational regions (like the US West) have Pacific linkages that conventional units of history have obscured.9 A second connectionist variant involves transnationalizing efforts within Asian-American and Pacific Islander history and ethnic studies. Over the past generation, scholarship previously directed towards demonstrating the presence, importance and contribution of Asian-Americans and Pacific Islanders with respect to US national history has turned its attention to these communities’ durable, dynamic connections to “home” societies; their complex, often fraught navigations of socio-political membership between states; and continuities as well as ruptures in their culture and social organization.10 Both of these sets of literatures, by rescaling and reframing historical research, have raised to the surface previously submerged dynamics, in often transformative ways. But they also come with some risks: the more integrative and “global” the frame, the more Islander histories tend to recede. There is also the serious danger of valorizing cross-national connection for its own sake, whether in the name of historical actors’ authenticity and resistance to Western power or, at one level of remove, in celebration of historians’ own cosmopolitan, globe-trotting imaginations. Given this work’s sometimes heavy reliance upon the conceptual armature of “globalization”—flows, networks, exchanges—it is not surprising that it often shares its aggressively political anti-politics of transnational and global connectivity.

To what extent, if at all, do these far-flung, transnational histories of the Pacific flow into each other? The obstacles here are formidable. Not unlike the Pacific Ocean itself, the fault-lines run deep. There are complicated asymmetries of power, resources and prestige separating rim and island academic systems, which result in highly uneven distributions of intellectual authority when it comes to basic historical agendas, methods and epistemologies: what history is good for, whose histories matter, and whose ways of telling history count. These Pacific histories are organized within diverse historiographies and require varied cultural competences, especially language. In the US academic setting, enduring, structural tensions remain between area studies approaches that foreground Asian-Pacific language, culture and history, understood in regional terms, and ethnic studies approaches that foreground questions of Asian-American and Pacific Islander agency and questions of racialized power and its contestation, understood in largely or exclusively within a US national context. The former stand accused of Cold War complicities and Orientalist tropes, the latter of over-attention to American exclusions and inattention to Asian-Pacific histories.

While national parameters continue to pose significant imaginative and practical challenges, so too do the equally imposing, if far less recognized barricades between transnational projects themselves. The fact that contemporary post-colonial historians, international historians, labor historians, and immigration historians, for example, share a defining opposition to nationalized history does not mean that they will feel any need to undertake the difficult work of talking with each other. In place of a world of nationally containerized histories, one can envision a world of methodologically containerized transnational histories, encased in walls their practitioners hardly know are there.

Thankfully, resourceful historians are clambering over, digging under, and punching holes through these walls even as they consolidate, creating the conditions of possibility for richer conversations between Pacific histories, even if their inventions are sometimes, at least initially, hard to fix on a map. Each in its own way breaks intractable rim/center divides. Taken as a whole, this might be called history at the interstices; it cuts across not only inherited geographic divides, but sub-disciplinary, thematic and methodological ones. Such scholars are writing the histories of restless Pacific “natives” voyaging to what for many may be unexpected destinations in metropolitan rims and peripheries (including Utah). They are demonstrating the ways that Islander history and agency shaped the particular contours taken by imperial rim powers in the Pacific as they sought to impose their will from the “outside.” They are uncovering the role of nationally minoritized peoples, such as Japanese-Americans, as agents of colonial, military and commercial empire in the Pacific, as well as its victims. They are revisiting the lives of East and Southeast Asian laborers in Pacific Islands as vulnerable, sometimes rebellious plantation workers, as well as settler-outsiders, both mixing with and pressures on indigenous worlds. They are looking at Asian exiles and revolutionaries who sought escape, refuge and stepping stones to the United States in Island spaces. And they are enlisting the tools of environmental history, labor history, and political-economic history to make sense of the invention of commodities from Pacific ecologies (fish, whale oil, guano, and pineapple, for example) and their entanglement with of oceanic, rim and ultimately global cultures and economies.[11]

|

This 1943 map of the “Great East Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere” from a World War II Japanese propaganda booklet shows the defeated Euro-American colonial powers in chaos and warm relations between Japan and conquered peoples. It may have targeted colonial subjects in Japan’s wartime empire. |

Three particular moves and sensibilities make this work possible. First is a critical awareness of the inherited geographic frames of dominant scholarship, and a curiosity about not only their obvious holds on historical practice, but their more subtle ones.[12] Second is the courage to rebel against the not-so-soft power of job descriptions, graduate seminars, journal titles, and professional associations as they impart spatial and geographic categories—including oceanic ones—within which the historical imagination is supposed to legitimately and exclusively pool. Third, and enabled by the first two, are inquiries into how historical actors themselves conceived of, practiced and struggled over their own position and mobility. What were their compass points? How did they define “home” and “away”? What power did they have to direct their movements, and what boundaries mattered? How for them did Utah and Hawai’i, Guam and Tokyo, Samoa and Kwajalein, Sydney and Nauru, fit together? Did they bring nationalized identities with them, or did they find or place themselves between national polities? One might think of these moves as displacements that track historical actors’ mobilities, activities, and modes of identification beyond conventional frames, while prying places and spaces out of inherited geographic grids.

|

“On to Tokyo” map from 1944 by Toronto artist Stanley Turner offer viewers a visually dense guide to ongoing Allied military campaigns in the Pacific, with prewar boundaries, the dates of major campaigns and colored areas showing Anglo-American and “Jap control.” |

Ultimately, this work both requires and enables a larger, much-needed revision: the deconstructing of the rim/island divide itself. It is not at all surprising that this particular way of splitting the world came to organize Pacific historical scholarship: it mapped neatly if inadvertently onto the racialized geographies of older, imperial histories; it came loaded with the discursive cachet of 1990s “rim-speak”; it offered a loose, regionally-specific, technocratic substitute for the sharper, more analytically supple dialectic between metropole and colony. It also tended to homogenize spaces that needed disaggregating, and left important questions unasked. When it came to islands, weren’t there key differences in the way inland and mountain peoples, lowland and littoral peoples, fronted the Pacific? And when it came to rims, how far from the ocean did they stretch? In the North American context, for example, were the United States and Canada themselves rim societies, or just their Pacific Coasts? Did California, Oregon, Washington and British Columbia form a single, coherent rim, or were their engagements with the Pacific different enough to situate them along meaningfully different rims? The reconstruction of historical subjects and dynamics that are impossible to fully situate on rims or islands—where did Mormon Hawaii fit?—may ultimately dislodge this geographic dichotomy and even allow its historicization which may, in turn, reduce its formidable sway.

That these modes of Pacific history are hard to square and, to some degree, incommensurable, does not mean that they are not all essential, as are the tensions between them. Historians would do well to embrace the necessity of navigating what will ideally remain a “complex of seas.” Not unlike the Pacific Ocean itself, might Pacific historiography be the site of proliferating intellectual trade languages, born precisely where distant currents collide and intermingle? The goal here would not be a single, authoritative map, an ocean into which rivers inevitably flow, or a language into which all others must be translated, but an unpacified Pacific capable of sustaining a reef’s wild multitudes.

This article is adapted and illustrated based on an article published in Amerasia Journal 42:3 (2016), pp. 32-41.

My thanks to my colleagues in the Georgetown Pacific empires conversations, Toyomi Asano, Eiichiro Azuma, Katherine Benton-Cohen, David Chang, Takashi Fujitani, Mariko Iijima, Jordan Sand, David Smith, and Jun Uchida, and especially, to Jordan Sand for bringing us together. Thanks also Eiichizo Azuma, Dirk Bönker, Mark Selden, Michael Thompson, and Jun Uchida for their critical readings and comments. For reasons of space, the citations for this essay are necessarily partial reflections of the relevant literature.

Notes

Matthew Kester, Remembering Iosepa: History, Place, and Religion in the American West (Oxford University Press, 2013).

On the challenges of writing Pacific history see, especially, Matt K. Matsuda, “The Pacific,” The American Historical Review, Vol. 111, No. 3 (June 2006), pp. 758-80; Damon Ieremia Salesa, “The World from Oceania,” in Douglas Northrup, ed., A Companion to World History (Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012), pp. 391-404; David Armitage and Alison Bashford, eds., “The Pacific and Its Histories,” in Pacific Histories: Ocean, Land, People (Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014), pp. 1-28.

Fernand Braudel, The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1995 [1949]), Vol. 1, p. 18.

For an illuminating, parallel discussion of the constructedness of continents, see Martin W. Lewis and Kären Wigen, The Myth of Continents: A Critique of Metageography (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997).

See Matsuda, “The Pacific.” On the broader Western ideological construction of the “tropics,” in which the Pacific played a key role, see Gary Y. Okihiro, Pineapple Culture: A History of the Tropical and Temperate Zones (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009). On the challenges of asserting an Islands-centered history, see Salesa, “The World from Oceania”; Teresia K. Teaiwa, “On Analogies: Rethinking the Pacific in Global Context,” Contemporary Pacific, Vol. 18 (2006), pp. 71-88.

For histories centered on Oceania and Pacific Island peoples, see, for example, Damon Ieremia Salesa, “The World from Oceania,” in Douglas Northrup, ed., A Companion to World History (Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012), pp. 391-404; Damon Salesa, “The Pacific in Indigenous Time,” in David Armitage and Alison Bashford, eds. Pacific Histories: Ocean, Land, People (Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014), pp. 31-52; David Chang, The World and All the Things Upon It: Native Hawaiian Geographies of Exploration (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2016).

On critical empire history in the contexts of Japanese and US historiographies see, respectively, see Jordan Sand, “Subaltern Imperialists: The New Historiography of the Japanese Empire,” Past and Present, Vol. 225, No. 1 (November 2014), pp. 273-88; Paul A. Kramer, “Power and Connection: Imperial Histories of the United States in the World,” American Historical Review, Vol. 116, No. 5 (2011), pp. 1348-91. For the US context see, for example, Vernadette Vicuña Gonzalez, Securing Paradise: Tourism and Militarism in Hawai’i and the Philippines (Durham: Duke University Press, 2013); Adria Lyn Imada, Aloha America: Hula Circuits through the U. S. Empire (Durham: Duke University Press, 2012); Christina Klein, Cold War Orientalism: Asia in the Middlebrow Imagination, 1945-1961 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003). For Japan, see Yujin Yaguchi, Akogare no Hawai [Longings for Hawa‘i: Japanese Views of Hawai‘i] (Tokyo: Chuo Koron Shinsha, 2011); Robert Thomas Tierney, Tropics of Savagery: The Culture of Japanese Empire in Comparative Frame (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010); Jun Uchida, Provincializing Empire: Omi Merchants in the Japanese Transpacific Diaspora (work in progress). For an innovative juxtaposition of US and Japanese race-making amid inter-imperial war, see Takashi Fujitani, Race for Empire: Koreans as Japanese and Japanese as Americans during World War II (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011). On militarization and resistance in the Pacific, see Setsu Shigematsu and Keith L. Camacho, eds., Militarized Currents: Toward a Decolonized Future in Asia and the Pacific (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010).

See, for example, Armitage and Bashford, “The Pacific and its Histories”; Matt K. Matsuda, Pacific Worlds: A History of Seas, Peoples, and Cultures (Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2011); David Igler, The Great Ocean: Pacific Worlds from Captain Cook to the Gold Rush (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013); Gregory T. Cushman, Guano and the Opening of the Pacific World: A Global Ecological History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014); Takeshi Hamashita, China, East Asia and the Global Economy: Regional and Historical Perspectives, Mark Selden and Linda Grove, eds., (Routledge, 2008).

Kornel Chang, Pacific Connections: The Making of the U. S.-Canadian Borderlands (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012).

For a path-breaking works in the new, transnational Asian-American history, see, especially, Madeline Hsu, Dreaming of Gold, Dreaming of Home: Transnationalism and Migration between the United States and South China, 1882-1943 (Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 2000); Eiichiro Azuma, Between Two Empires: Race, History, and Transnationalism in Japanese America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005).

For scholarship along these lines, see Gary Y. Okihiro, Island World: A History of Hawai’i and the United States (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008); Keith Camacho, Cultures of Commemoration: The Politics of War, Memory and History in the Mariana Islands (University of Hawai’i Press, 2011); Moon-ho Jung, “Seditious Subjects: Race, State Violence, and the U. S. Empire,” Journal of Asian American Studies, Vol. 14, No. 2 (June 2011), pp. 221-47; Kariann Akemi Yokota, “Transatlantic and Transpacific Connections in Early American History,” Pacific Historical Review, Vol. 83, No. 2 (May 2014), pp. 204-19; Simeon Man, “Aloha, Vietnam: Race and Empire in Hawai’i’s Vietnam War,” American Quarterly, Vol. 7, No. 4 (Dec. 2015), pp. 1085-1108; Azuma, Between Two Empires; Imada, Aloha America.

See, for example, different efforts to rethink US history from the Pacific, in Bruce Cumings, Dominion from Sea to Sea: Pacific Ascendancy and American Power (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010), and Gary Y. Okihiro, American History Unbound: Asians and Pacific Islands (Oakland: University of California Press, 2015).