Translator’s Introduction

Richard Sams

March 10 is the 70th anniversary of the Great Tokyo Air Raid. Although Tokyo was bombed more than 100 times from November 1944 to the end of the war, the firebombing centered on the Shitamachi district in the early hours of March 10, 1945, was by far the most devastating air raid on the capital. In less than three hours from just after midnight, 279 B-29 bombers dropped a total of 1,665 tons of incendiaries.1 By dawn, more than 100,000 people were dead, one million were homeless, and 16 square miles of Tokyo had been burned to the ground.

More people were killed in the indiscriminate firebombing of March 10 than in the immediate aftermath of the dropping of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima. After the war, while Hiroshima and Nagasaki became symbols of Japan’s suffering and the peace movement, the Great Tokyo Air Raid was virtually excluded from public discourse. Hardly anyone wrote about the air raids that reduced the capital and most of Japan’s other cities to ashes, and the few articles that did appear in newspapers attracted little interest. For a quarter of a century after the war, while memorial services were held every year on August 6 and 9 for the victims of the atomic bombings and covered widely in newspapers and on television, the devastating firebombing campaign over Tokyo and much of urban Japan was quietly forgotten. While school textbooks, novels, poetry and films memorialized the atomic bombing and its victims, silence reigned with respect to the firebombing raids.

In the 1950s and 1960s, Japan’s high-speed growth transformed the Tokyo cityscape until all the remaining signs of devastation lay buried underground, out of sight and mind. Tokyo’s hosting of the Olympic Games in 1964 served as a symbol of Japan’s post-war reconstruction. In the same year, the government awarded General Curtis LeMay – the architect of the firebombing campaign – one of its highest honors, the First Class Order of the Rising Sun, for his work in establishing Japan’s postwar Air Self-Defense Force.

On occasion, however, Tokyo’s rapid urban development brought back memories of the devastation of the Shitamachi district from below ground. On June 13, 1967, the shocking discovery of human skeletons in a buried air-raid shelter unearthed during construction at a subway station in the Fukagawa district was reported in the Mainichi Shimbun newspaper. Among those who read the article was Saotome Katsumoto, a writer who had experienced the March 10 air raid as a boy of twelve. Saotome’s experiences during the war had imbued him with a deep pacifism that informed his life and career. He had already published six novels, the first of which had been nominated for the prestigious Naoki Prize. While he had drawn from his experience of the air raid in these novels and described it in various articles, he had never fully come to terms with it. As Saotome recounts below, the newspaper article had a galvanizing effect on him.

|

Saotome Katsumoto Photograph by Cary Karacas |

A few days after he saw this article, Saotome received a visit from the journalist and critic Matsuura Sozo, who had begun to research the question of public amnesia regarding the Tokyo air raids. Matsuura was interviewing various people for an article about the raids for the monthly magazine Bungei Shunju.2 Although the two discussed the possibility of collaborating on a large project, it was not until 1970 that they pursued it in earnest. Saotome would later recall that 1970 was a critical turning point in public awareness of the firebombing of Tokyo. It was not only the twenty-fifth anniversary of the end of the war but also the year when the Anpo protests once again challenged the renewal of the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty. In addition, many survivors of the firebombing of Japan were feeling kinship with the victims of the napalm carpet-bombing of North Vietnam. Saotome saw it as the “last chance to denounce the Tokyo air raids.”3 On March 10, the Asahi Shimbun newspaper featured a letter by Saotome in its “Voices” (readers’ letters) section. After describing his harrowing experience of escaping from the inferno as the incendiary bombs rained down around him, he closed with an appeal: “Should not those of us who experienced the raids, at least on this day, just for one day, speak of what war is really like? And shouldn’t we also think about the bombs indiscriminately falling on Vietnam?”4

In response to Saotome’s plea, personal accounts of the air raids poured into the newspaper’s offices. To accommodate these responses, the Tokyo edition of the newspaper featured a special daily column Tokyo Hibaku Ki (Chronicle of Tokyo’s Bombings) featuring the recollections of victims of the bombings, particularly the March 10 raid. These victims’ testimonies were featured in the newspaper every day for forty days.

Seizing on the momentum generated by this public discussion, Saotome and Matsuura brought together sixteen intellectuals and air raid survivors to form the Society for Recording the Tokyo Air Raids, officially established on August 5, 1970.5 The Society’s central project was to publish the Tokyo Air Raid Damage Records (planned as five 1,000-page volumes) from the viewpoint of the main protagonists: the citizens of Tokyo. Funding was granted for this massive publishing project by the Governor of Tokyo, Minobe Ryokichi, a self-proclaimed “utopian socialist” who had himself experienced the firebombing of Hachioji in western Tokyo just two weeks before the end of the war. It was the first time that the Tokyo Metropolitan Government had made a commitment to support an extensive recording of the history of the air raids.

|

Representatives of the Society for Recording the Tokyo Air Raids meeting with Governor Minobe, August 5, 1970 Second Left to right: Saotome Katsumoto, Matsuura Sozo, Minobe Ryokichi, Ienaga Saburo Source: Tokyo Air Raid Resource Center |

In the meantime, Saotome started visiting victims of the March 10 Shitamachi air raid to gather material for his own book. When he visited Fukagawa Library in July, both the chief librarian and one of the library staff, Hashimoto Yoshiko, recounted how they had survived the inferno that swept through Fukagawa and Honjo wards. Saotome featured Hashimoto’s incredible story of survival in his book. She later became a member of the editorial committee of the Society for Recording the Tokyo Air Raids and was active in raising public awareness.

The Great Tokyo Air Raid was published by Iwanami Shoten in January 1971. On March 10 nearly all of the media broadcast programs or published articles on the Tokyo air raids, focusing on the firebombing of the Shitamachi district. By the end of March, 221 victims of that air raid had submitted accounts of their experiences for inclusion in the first volume of the Tokyo Air Raid Damage Records. Amid this surge in public interest, Saotome’s book became a bestseller. In the first year following publication, about 200,000 copies were sold – an extraordinary number for a non-fiction book about the war. From 1971 until its publication was discontinued in 2007 it went through 49 editions. The fact that a total of about 500,000 copies were sold over 36 years testifies to the extraordinary interest generated by the media during the year of its publication.6 In the early 1970s, successive books and articles about the Tokyo air raids were published, including the five volumes of the Tokyo Air Raid Damage Records (1973-74). By the mid-1970s, however, the fickle interest of the media and general public had faded once again. This was hardly surprising, since it had risen through a particular combination of circumstances – the 25th anniversary of the end of the war, the controversies surrounding the renewal of the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty, the Vietnam War, and the influence of the first socialist Governor of Tokyo. Even so, without the determined activities of a small group of intellectuals and air raid survivors led by Saotome Katsumoto and Matsuura Sozo, it might never have happened at all.

The Great Tokyo Air Raid is an ambitious book. Although Saotome’s main focus was on the experiences of the victims, he also attempted to weave these accounts into a linear narrative of the air raid as a whole, while explaining the low-altitude firebombing strategy adopted by the US Army Air Force. However, as the author himself observed, the fact that only a few US documents had been translated into Japanese made the task very difficult. In 1979 Saotome himself wrote another book on the March 10 air raid, Tokyo ga Moeta Hi (The Day Tokyo Burned), in which he incorporated information from the US Army Air Force Tactical Mission Report that had become available after his first book was published. Nevertheless, the victims’ testimonies that form the core of The Great Tokyo Raid remain as powerful and heartrending today as they were when they were first told to the author forty-five years ago.

Seventy years after the Great Tokyo Air Raid, this is the first time for these survivors’ voices to be heard in the English language.

Richard Sams is a professional translator living in Tokyo. Since translating The Great Tokyo Air Raid a year ago, he has been researching the Tokyo air raids. His article on US bombing strategy for appeared in the Japanese journal Kushu Tsushin (Air Raid Report). He is currently editing a book (“Voices from the Ashes”) with Cary Karacas on the firebombing of Tokyo from the viewpoint of the victims. He has an M.A. in history from Cambridge University.

Author’s Introduction by Saotome Katsumoto (1971)

At about two in the morning on June 11, 1967, on a construction site on the Tozai subway line at Monzen-nakacho in the Fukagawa district of Koto Ward in Tokyo, workmen digging up the ground to repair damage to the track discovered something very strange. Below the pavement, at a depth of 15 meters, they found what appeared to be the remains of an air raid shelter. Inside it were six human skeletons huddled close together. Two of them were children and the other four adults. Their gender could not be determined. The positions of the bones suggested they had been cowering in terror, and one of the adult skeletons was cradling two Buddhist memorial tablets in its arms. There were signs that the shelter had been engulfed in flames. Burn marks were visible on one set of bones, and a rusted steel helmet and decayed water bucket lay close by. For the local residents who came to witness it, this discovery brought back memories of the massive air raid over the Shitamachi, the low-lying eastern district of Tokyo, in the early hours of March 10, 1945.

What were these remains discovered 22 years after the war? Who were the six victims and where were they from? The incident was reported in the Mainichi Shimbun newspaper on June 13. A clue to the identity of the six bodies was provided by the inscriptions on the memorial tablets. The next day, the newspaper reported that Tsuzuki Shizuo7, a company president living in Kamiogi, Suginami Ward, had claimed that the remains were those of his relatives and expressed his wish to collect them.

A friend of Shizuo’s had seen the article on June 13 and told him about it. According to Shizuo, at the time of the air raid just after midnight on March 10, 1945, he was at his wife’s parents’ home together with his wife and their four year-old daughter. When the raid started, seven family members – Shizuo, his wife and daughter, and his wife’s mother with her two other daughters and grandchild – had set out to evacuate to a nearby elementary school. On the way, his mother-in-law noticed that she had forgotten something important and Shizuo went back to get it. When he returned, the others were nowhere to be found. He never saw them again.

Thus Tsuzuki Shizuo came to confront the remains of his wife and child twenty-two years later.

When I read that newspaper article, I immediately wanted to hear Tsuzuki Shizuo’s account of that terrible night and pray for the souls of the victims, but I could not muster the courage to meet him. After all, I was a mere writer and had my own vivid memories of the Great Tokyo Air Raid in which Shizuo lost his wife, child, and other relatives. I was one of those who ran this way and that in frantic efforts to escape the inferno and barely survived. Since then I have considered it my duty to faithfully record the horrific events of that night and convey the reality of war. If I possibly could, I wanted to leave an accurate historical record for future generations.

Considering that at least 80,0008 people died and over a million lost their homes and suffered immeasurable hardships, there are incredibly few written records of the Great Tokyo Air Raid. This was particularly true of the eight years prior to the publication of the Tokyo Metropolitan War Damage Records compiled by the Tokyo Metropolis in 1953 and Photographs of the Great Tokyo Air Raid published in the same year. Since then no records of similar scale have been compiled and only two or three books by individual authors have been published. The only comprehensive document, the Tokyo Metropolitan War Damage Records, is not readily accessible, nor are its statistical sections easy for general readers to understand. Furthermore, its descriptions deliberately omit accounts of the emotional suffering of the victims. Such documents as these cannot convey the terrible reality or an overall picture of the tragedy of the Great Tokyo Air Raid.

It is easy enough to state that more than 80,000 people lost their lives, but sometimes I imagine how it would look if all these victims, in their final death throes, were gathered together in the same place. However much I try to banish this vision from my mind, I am left staring helplessly at it. My decision in the summer of 1970, a quarter of a century after the end of the war, to visit victims of the Great Tokyo Air Raid and record their hitherto silent voices was not simply due to my sense of duty as a fellow survivor. To grasp my own pacifist ideology, I needed to ascertain the truth of the war twenty-five years earlier and to think in my own way about the fates of the 80,000 victims on that terrible night.

However, my approach to Tsuzuki Shizuo met with an unexpectedly firm refusal. I telephoned him to ask if we could meet to talk about his experience but he told me he could not bear to relive it. It is hard for us to reopen past wounds, and the feelings of a man who had to confront the skeletal remains of his wife and child after they had been buried underground for twenty-two years are impossible to imagine. What would be the point of talking about such things to an unknown writer? The emotional scars left on the people of Tokyo, particularly ordinary working people, are not something they can easily talk about. I understand that only too well, for I was a boy of twelve who experienced the trauma of staring death in the face.

In the summer of 1970, twenty-five years after the end of the war, I walked around Tokyo every day with a notebook and pen, visiting families of the victims to interview them about their experiences of the air raids, particularly the Great Tokyo Air Raid of March 10, 1945. I recorded the testimonies of over twenty people either directly or at second hand. I was turned away at the door many times, and not one of those who agreed to be interviewed was calm or composed. As if on cue, they all broke down during their accounts and, sitting there with my pen in hand, I was unable to look up at them. The scars are still deep. These wounds will never heal as long as they live. For them the “postwar” period will never end.

Understanding this state of mind made me all the more determined to get the victims to open up, revisit deeply buried memories, and describe their experiences. I had to reveal clearly the reality of the Great Tokyo Air Raid, a reality that was much worse than tragic. However painful it might be, confronting people’s actual experience of war will surely help to build a firm foothold for peace.

In this book, in addition to the author and Metropolitan Police Department photographer Koyo Ishikawa, eight citizens of the Shitamachi district of Tokyo describe their experiences in the Great Tokyo Air Raid9. Through the living testimonies of these ordinary people I have strived to present a clear picture of that night of indiscriminate firebombing. The recounting of these experiences was painful for both the speakers and the listener, but for the sake of those who bore this pain and for all those who lost their lives, I have attempted to faithfully record the events of March 10, 1945.

Saotome Katsumoto is the author of The Great Tokyo Air Raid (Iwanami Shoten, 1971) and a key figure in memorializing the Tokyo firebombing raids. He is currently Director of the Center of the Tokyo Raids and War Damages. At the age of 83, he is still active as a writer and speaker.

The following links are to victims’ testimonies from The Great Tokyo Air Raid (the ages given are at the time of the air raid):10

Saotome Katsumoto, mobilized student, 12

Kikujima Koji, technical school student, 13

Ishikawa Koyo, police photographer, 40

Hashimoto Yoshiko, housewife, 24

Kokubo Takako, member of volunteer corps, 19

I would like to thank Cary Karacas for sharing his expert knowledge and allowing me to reproduce images from his website, Japan Air Raids.org.

1 Figures from Tactical Mission Report, Mission No. 40

2 This article, titled Kakarezaru Tokyo Daikushu (“The Great Tokyo Air Raid Nobody Writes About”), was eventually published in the March 1968 edition of Bungei Shunju.

3 Saotome Katsumoto, Heiwa o Ikiru (Living in Peace), Sodo Bunka, 1982, p. 55 (my translation).

4 Asahi Shimbun, 10 March 1970.

5 The founding members included the historian Ienaga Saburo, photographer Ishikawa Koyo, writer Arima Yorichiku, and voice actor Tokugawa Musei.

6 These approximate sales figures were conveyed to me directly by the author.

7 In Saotome’s introduction, the name is rendered simply as T-san. I have taken the name from the above-mentioned article by Matsuura Sozo in the March 1968 edition of Bungei Shunju.

8 This figure was based on the materials available to the author at the time. In his 1979 book, Tokyo ga Moeta Hi (The Day Tokyo Burned), Saotome estimated the number of death at about 100,000 based on the latest research. In the special 50th edition of The Great Tokyo Air Raid published in January 2015 to commemorate the 70th anniversary of the end of the war, Saotome states that “at least100,000 is an accurate estimate.”

9 Three of these citizens’ testimonies are featured below.

10 These testimonies are not presented as they appear in the book, but as complete accounts from the beginning of the air raid to the end.

Testimony of Saotome Katsumoto

“Katsumoto! Get up!”

At the sound of my father’s voice, I jumped out of bed. The same instant, a ray of light that made my eyes swim streaked across the south window, followed by an eerie roar that seemed to pierce the earth. I remember the shock of that moment as if it happened last night. Grabbing the first-aid and emergency bags by my pillow, my air-raid hood, and my only treasure, a cloth pouch containing old coins, I rushed down the stairs shouting “I’m coming, I’m coming!”

There was a reason for my quick response. It was March 10, Army Day. It had been rumored that the enemy was planning a huge air raid to coincide with this special day. As if to confirm those fears, a fierce northwesterly wind had been blowing since the previous evening. The flames reflected in the glass of the window and the deafening roars and explosions were enough for even a child to realize it was serious.

I went outside to look. In every direction – east, west, south and north – the dark sky was scorched with crimson flames. The steady roar of the B-29s’ engines overhead was punctuated by piercing screeches followed by cascading sounds like sudden showers. With each explosion, a flash of light darted behind my eyelids. The ground shook. Flames appeared one after another. As our neighbors looked outside their air raid shelters defiantly holding their bamboo fire brooms, they cursed when they saw how fiercely the fires were burning. They were helpless against the raging flames. Fire trucks, sirens wailing, were already speeding toward the fires, but what could they do in this gusting wind and intensive bombardment? Even in the eyes of a child, the situation seemed hopeless.

“Katsumoto, don’t dawdle!” cried my mother. She was standing in front of the air raid shelter, looking around in confusion. I’ll never forget the expression on her face. “Whichever way you look, there isn’t a single dark place, not one. We should’ve eaten those extra rations this evening. It would’ve been better to die on a full stomach.” “Don’t be silly,” said my father, his eyes darting about beneath his steel helmet.

“This time it’s different from usual. Katsumoto, get your things together quickly.”

“Alright.”

“Where’s Shizuko?”

“She’s still sleeping.”

Even now, my easygoing sister was lazing in bed.

“I’ll go wake her,” I said.

I went back into the house and rushed up the stairs beside the kitchen. I clearly recall being able to read the characters on the wall calendar even though all the lights were out.

In the crimson sky, black smoke was gathering in a dense fog and sparks were swirling about. It was a blizzard of sparks. Circling serenely above the pillar of flames, the B-29 bombers continued to pour down their incendiaries. First a bright blue flash shone in the sky, then countless trails of light fell and were absorbed in the black rooftops, from which new flames rose up. “My, how beautiful!” exclaimed my sister. Strangely I still remember that incongruous remark. At that moment, as if to suppress my sister’s admiration, a metallic explosion rang out. Suddenly I saw the huge form of a B-29 flying very low above the rooftops. Its belly opened wide and several black objects fell screeching to the ground. I instinctively covered my face. When I looked up again flames were rising all over the neighborhood. Then I heard my father’s voice from below: “Katsumoto, what are you doing?” Bring down the futons from upstairs and put them on the cart!”

This was how I first encountered the Great Tokyo Air Raid of March 10. At that time, a 12 year-old boy such as myself should not have been in Tokyo. Most schoolchildren in the capital city had been evacuated to the countryside. But because I was born in the first three months of the year, I had been moved up to the senior class after graduating from national elementary school and became what is now called a junior high school student. As a result I avoided evacuation and was placed in the youngest class of mobilized students. Together with most of my friends, I was busy working every day making hand grenades to be thrown by Japanese soldiers in their suicide attacks. But what use could a runny-nosed schoolboy be at a military ironworks? War is so cruel.

For a poor working family like mine, residing in Mukojima ward in the Shitamachi district, there was nowhere to escape to and no time to get away when the air raid struck. All we could do was cower in a corner of this low-lying region of the imperial capital. It was my fate to directly experience the horrors of the Great Tokyo Air Raid.

As is well known, the first US air raid on Tokyo in the Pacific War was the surprise attack by a squadron of 16 B-25 bombers led by Colonel James Doolittle on April 18, 1942. However, US air raids did not begin in earnest until the completion in October 1944 of a base for launching B-29 “Superfortress” heavy bomber raids from Saipan in the Mariana Islands. The first mission by a B-29 from the Saipan base was on November 1, 1944.

I vividly remember that day. At the time we still had classes at school, but the raid took place while we were doing military training. Covered in sweat, we were practicing marathon running on a country road. Suddenly we heard the intermittent wailing of an air raid siren and saw a civil defense corpsman, his face ashen white, screaming, “Enemy rocket! Enemy rocket!” We looked up and saw a metal object glittering like a diamond with streams of white smoke streaking behind it as it moved in stately fashion across the deep blue sky. Successive barrages of fire went up from anti-aircraft guns, but they were completely off target and obviously firing too low. At that time, Japan’s fighter planes and anti-aircraft guns were helpless against aircraft flying at a height of more than 10,000 meters. The anti-aircraft artillery for the defense of Tokyo consisted of seven- and eight-inch guns with a range of 5,000 to 6,000 meters, while most of Japan’s fighter planes could only fly to an altitude of about 8,500 meters.

It was not an enemy rocket. I found out much later that those streams of white smoke were vapor trails and that this B-29 was on a reconnaissance mission. They undoubtedly took some very detailed aerial photographs of Tokyo that day.

Most of us already knew the war was going badly. Japanese troops had been decimated in suicide attacks on Attu Island, the southern island of Guadalcanal had fallen, and the Mariana Islands of Saipan, Guam, and Tinian had all become US frontline bases by the end of 1944. The US armed forces were relentlessly closing in on the Japanese mainland. On the day of the US army landing on the southern coast of Iwo Jima on February 19, 1945, the Japanese defenders were bombarded with as many as 8,000 shells in one day and driven to the north of the island. If Iwo Jima fell and the Americans reached Okinawa, an invasion of the Japanese mainland would be imminent. To camouflage the retreats, the Imperial Headquarters used the expression “change in course”, while the slogan “fight to the death” was replaced by “let them cut your flesh so that you can sever their bones.” For the B-29s, it was now a 1,500-mile flight to Tokyo from the air base in Saipan. They arrived in waves, their bellies filled with explosive and incendiary bombs.

Up to March 10, the B-29s bombing Tokyo had flown at a height of at least 10,000 meters and, although they had dropped large quantities of explosive and incendiary bombs, these had been aimed primarily at military targets in the city. The Great Tokyo Air Raid in the low-lying Shitamachi district was the first time the US air force moved from targeting the main industrial districts that were the basis of Japan’s military capability to low-altitude indiscriminate incendiary bombing that targeted civilians.

Tragically, there was also a very strong wind that day. From around noon on March 9, a northwesterly wind blew under overcast skies, becoming even fiercer from the evening into the night. Snow that had fallen two or three days earlier still remained on the ground in places, and the sudden gusts of wind in the streets cut through you like a knife.

I rose reluctantly from my warm bed and went outside. There was a duty I had to perform as a “young imperial citizen.” The north wind was so fierce that I could hardly stand up. The telegraph wires swayed and lids of garbage boxes flew up into the air. As a precaution against an air raid, I took a fire axe and broke the ice on the surface of the water in the tanks with all my strength. Then I took the shattered pieces of ice one by one and threw them out into the road. It was unpleasant work, but if I hadn’t done it, the water would have immediately frozen again. They said it was the coldest early March in fifty years.

When I had finished this chore, I went back inside the house, blowing on my numb fingers to warm them. The only light in the darkened room came from the radio, which provided us with the latest information. The Daily Record of Air-raid Warnings later published by the Roppongi Civil Defense Corps provides a detailed account of the information announced on the radio that night in the zone under the jurisdiction of the Eastern Army. At 10.30 p.m. on March 9, an air-raid standby alert was issued:

(1) Several presumed enemy targets approaching mainland from off the southern coast.

(2) Unidentified enemy targets flying north towards Boso Peninsula.

(3) First enemy targets entering home island airspace from Boso Peninsula.

(4) First enemy targets keeping close to coast of Boso Peninsula.

(5) First enemy targets changing course from south coast of Boso Peninsula and moving southward out to sea.

According to this information from the Eastern Army-controlled zone, B-29s circling the Boso Peninsula had entered the air space of Tokyo from the south of the peninsula and, without incurring any damage, had changed direction and were now flying far out over the ocean. As the radio announcer repeated the message, I breathed a sigh of relief.

A moment later, my father, dressed in his black uniform, suddenly came in and muttered, “It’s over.”

“Isn’t it Army Day tomorrow, dad?” I asked.

“Yes, but I don’t think they’ll be doing anything special,” replied my father. As he said this, I vaguely remember him putting down his bamboo water gun and heavy-looking steel helmet next to his pillow. It might seem strange for a grown man to have a water gun, but this type was one meter long with a diameter of ten centimeters and was issued only to the heads of firefighter groups. It had the imperial chrysanthemum crest branded on it at the end of the barrel. My father took his water gun with him on firefighting drills. When all the participants had gathered, they would hang a red cloth from the roof of a two-story house to represent the fire. Then they aimed the water gun, shouted out in unison, and shot a jet of water at the cloth. It was all right when they hit the target but when they missed, the cloth just hung there limply and they had to try again until they got it right. Until the night of March 10, everyone had been led to believe that they could defy incendiary bomb attacks with water guns, bucket relays, and fighting spirit.

Feeling relieved that it was a false alarm, my parents, two older sisters and I had gone to bed. During that brief respite, the massive indiscriminate firebombing raid scheduled for Army Day began.

We loaded our most important belongings onto a handcart and made our way down the Mito-kaido road, then turned left and headed south. We were running downwind, pushed along by the northwest wind behind us. To the south of Mukojima, the conflagration was already spreading throughout Honjo and Fukugawa wards. It is hard to explain why we headed towards the fires, but it seems that people lose the capacity to make cool judgments in such situations. The area to the north of our home was already engulfed in flames and sparks were raining down over our heads, so we felt we had to run in the opposite direction. The road was overflowing with people escaping with their various belongings, all of them heading south. We would have needed great conviction to go toward the wind in the opposite direction from that advancing wave of people. There were raging fires in the Asakusa district to the north and we could see fires burning in every direction. The only place that still seemed relatively dark was the Azuma-cho area in the southeast. My father held the handles at the front of the cart, my mother and I pushed it from behind, and my two sisters ran at the sides as we made for that dark place.

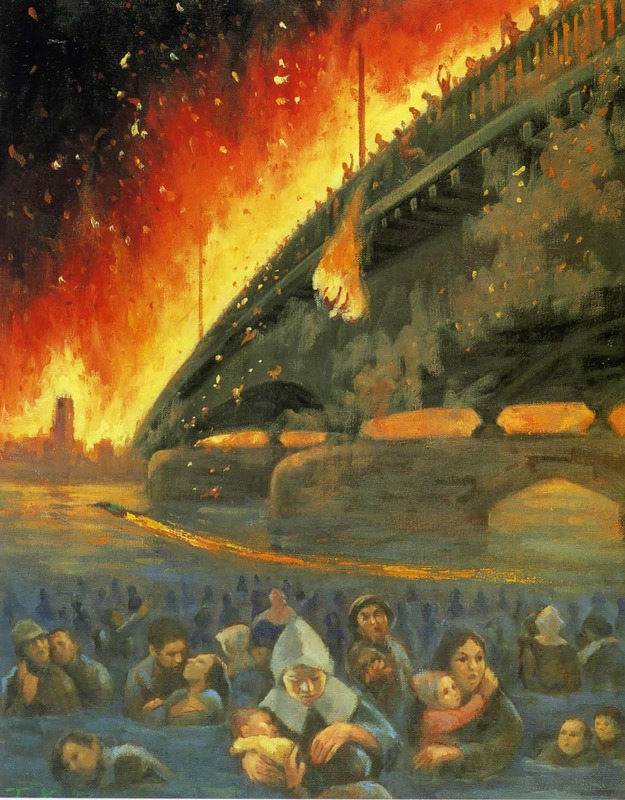

|

The Mukojima Area in Flames Painting by Katsumi Hidesaburo, who was sixteen at the time of the air raid Source: Sumida Local Culture Resource Center |

With an air-raid hood completely covering my head, I was wearing my khaki civilian wartime uniform with the red eagle insignia of the Great Japan Youth Organization on the breast pocket and an identification tag indicating my name, address, school and blood group sewn into it. Over that I wore my elder brother’s embroidered judo robe, which crinkled when I touched it. It looked just like the jackets worn by the firemen, except that it was white (though it was completely black by the following morning). Hanging from my belt underneath the loose-fitting judo robe, I had my first-aid and emergency bags, gaiters to protect my legs, my pouch of old coins, and a rubber trumpet. I didn’t plan to blow the trumpet to call for help; I’d borrowed it from a friend and felt obliged to return it. The coins made a jingling sound as I walked. Looking back on it now, I wasn’t so much afraid as in a daze. I realized that our home might burn down but it didn’t yet occur to me that my life was in danger. If the house was consumed by the flames, I vaguely wondered what would become of Tomi, the tortoise-shell pet cat we had left behind. But where on earth could we escape to? While we were heading for the only dark place, the enemy circling in the sky above would surely drop incendiaries there before we could reach it. The only safe haven was inside those B-29s flying above us. The bastards! To hell with those devils MacArthur and Nimitz!

“This heat is terrible. It’s as if the air is on fire,” said my mother to me, grimacing as she ran. The tone of her voice was despairing. Countless sparks were flying high and low in the wind like swallows. My father advanced while brushing them off his clothes and could only raise his head occasionally in the blizzard. “The fires are everywhere. What on earth are we going to do?” said my mother. In the beginning my mother made numerous remarks like this. Thinking back on it, I guess she couldn’t bear that blind scramble for safety in silence. I still remember the flickering red flames reflected in the lenses of her glasses.

At last we crossed the Hikifunegawa canal. The name, meaning “pull-boat river,” comes from the Edo period when horses pulled boats up and down the canal. After we had crossed the canal and the railway crossing of the Keisei line on the other side, my mother startled us by suddenly announcing she had to go back because she’d forgotten the photograph of my elder brother who had gone off to war. “Don’t be a fool! This is no time to be thinking of someone who isn’t here,” shouted my father, turning round but not stopping. She didn’t utter another word after that. It must have been unbearable to think of her son’s photograph enveloped in flames in our empty house. I understood that, but I also knew that going back would be a journey to hell.

On the way we ran into Mrs. Torii from our neighborhood and her only son Iwao. Mr. Torii, our local watchmaker, had been conscripted in spring of the year before and Iwao was in the same grade as me at school. “What on earth happened to you?” asked my mother in surprise. It was a natural question, because Mrs. Torii looked very strange indeed. It seems that folks completely lose their heads in such situations. While escaping we had seen people carrying tatami mats on their backs, with stone weights used for radish pickling loaded on their bicycles, or with blankets draped over their shoulders like the comic book superhero Golden Bat. But Mrs. Torii and her son were even more unforgettable. She had a futon wrapped around her, fastened with thick straw rope, and several pairs of wooden clogs tied to her waist with silk. Her son was wearing an adult’s steel helmet with two floor cushions tied around his waist at the front and back and wooden clogs hanging from the silk thread. I looked at him in open-mouthed amazement, but he said without laughing, “Let’s all go together.” “Did you bring the clocks with you too?” I joked. “No, we don’t need them. What you need is clogs for walking back over the debris from the fires.” Now I understood. I remembered that they’d warned on the radio that rubber-soled shoes would be dangerous in incendiary air raids, so we should wear shoes with leather or wooden soles. But even if you had wooden clogs, what good was it if you’d lost your home? I’ve completely forgotten what we said after that, but we escaped together with Mrs. Torii and Iwao for another four or five minutes.

We rushed on, forcing our handcart through the crowds and the swirling sparks until we reached the second railway crossing on the Tobu Kameido line from Hikifune to Kameido. But in the middle of the crossing, the handcart bounced on the rail and the lid of a cooking pot on top of our luggage came off and fell clanging to the ground. It rolled along and disappeared round a corner into a back alley. Tutting in annoyance, I went off alone into the alley to fetch it. At a time when we were running for our lives a pot lid was of no importance, but it seemed a shame to throw it away. At that moment, I saw a single B-29 emerge from the reddish purple flames and come straight towards us, flying so low I thought it might collide with the telegraph poles. Reflected in the flames, its wings gleamed bright red like dripping blood. “They’re coming down!” screamed a man just in front of me, looking up at the sky. An ear-splitting explosion shook the ground. I closed my eyes in terror and a golden streak of light flashed behind them. An incendiary pierced the neck of the man who had just cried out, bursting into flames. Then it grazed the shoulder of a woman who had run up beside him and embedded itself in a telegraph pole. In an instant the whole area around me was a picture of hell. An arm and a head had been torn off and bodies were sprawled about. A little girl of four or five stood bolt upright among them, splattered with blood but miraculously spared. I just stood there in shock, holding the lid of the pot with both hands.

“Katsumoto, are you alright?” Emerging from the wall of fire, my father’s face looked like just eyes and a mouth.

After that we lost sight of Mrs. Torii and Iwao as we ran this way and that in the alleys around Azuma-cho. There was no longer any refuge from the fierce wind. The wind fanned the fires and the fires fed the wind. Countless sparks and embers bore down on us, humming like a swarm of bees.

According to the Tokyo Fire Department, the fires in Mukojima broke out a little later than those in Honjo and Asakusa wards. Starting in western Azuma and spreading to parts of Terajima, they merged as they were fanned by the north-west wind and joined forces with the conflagration sweeping through Joto and Honjo wards, surrounding the whole of Mukojima. Like insects drawn to the flame, we found ourselves being dragged into the conflagration. Because we had first seen stronger fires burning in the direction of Asakusa, we panicked and ran south, only to have our escape route blocked by the B-29s arriving ahead of us. We carried on running as the bombs fell from all directions, dodging sputtering incendiaries lodged in the ground and jumping over dead bodies on the road as if we were running an obstacle race.

One incendiary bomb skimmed past the shoulder of a woman near me, lodged itself in a telegraph pole, scattered sparks, and turned into a pillar of fire. Roofs of houses spewed flames, wooden fences and telegraph poles burned, and even the brick-and-mortar warehouses of factories were engulfed in the inferno. Located between the Nakagawa and Kitajukken canals, Azuma-cho contained many factories. It seemed that these were being targeted because all around us pillars of flame were shooting up into the dark sky. Desperately trying to escape the smoke and flames, we ran through the maze of back alleys, only to emerge in the same place we had started. “Damn it!” cried my father. “We’re surrounded by fires.” At that moment the roof of a house collapsed in front of us with a tremendous rumbling sound and a hot wind roared over us as if blown by bellows. Carried by the north wind, black smoke and flames swept over the road devouring everything in their path.

I knew then that we were in the direst straits. There was nothing to do but pray to the gods. Perhaps I thought a kamikaze (“divine wind”) might blow and change the direction of the wind. At that time we young Imperial citizens had been told umpteen times by our schoolteachers that Japan was the “land of the gods” ruled by an unbroken line of emperors and that a kamikaze would blow if worse came to worst. But instead of that divine wind, it was my sister who saved us by discovering the only dark place in the sea of fire. This was the Tobu railway line between Hikifune and Kameido.

“Right, we’ll break through there!,” shouted my father. He scooped water from a water tank into his steel helmet and emptied it over my head. I don’t remember how that felt, but I’ll never forget the sight of the flames like red carp reflected on the surface of the water. We poured water over each other in preparation for our final dash down the railway tracks. Before we started running down that only remaining path to survival, my mother suddenly said she needed to urinate. Saying “It’s not easy running with a full bladder,” she pulled down her trousers and squatted over a garbage box. Before we escaped, my mother had said we should have eaten our extra rations of rice if we were going to die anyway. Now, as we were about to run for our lives, she had to take a piss because she didn’t want to feel uncomfortable! Her comical behavior helped us regain a little composure.

We all took a deep breath, bent down low, and ran for all we were worth down the railway track against the fierce north wind. That wind must have been blowing at 30 meters a second. It blew clumps of fire into the air and they came swirling towards us. With a rushing sound, the flames skimmed past my cheeks and the smoke seemed to penetrate my lungs. Incendiary bombs were still falling all around us, and one of them burst on the track with a loud boom.

“Is everyone all right?” yelled my father as we ran. “We’re okay!” I shouted back, sweeping away the smoke in front of me with my cotton work gloves. My judo robe, which I had soaked with water just a few moments earlier, was already bone dry. I was fighting for breath, could only see about five meters ahead, and no longer knew who was running where. Then, just in front of me, I saw flames flickering. Someone’s back was on fire. “Mum, your backpack!” I screamed. Without replying, my mother threw her burning backpack down on the ground. It turned into a ball of fire and was sucked downwind.

After we had run under several signals along the railway track and over an iron bridge across a drainage channel, we saw that the fires around us were dying down. Many people were sitting or lying exhausted on the tracks. The flames had not yet reached that area and I could see the shining black roofs of the nearby houses. Finally realizing that we had somehow escaped death, my strength suddenly ebbed away and I felt like I was being sucked into the ground. My father said we were still in danger, so we went down Meiji Street past the Terajima Crossroads, making straight for the Sumida River. Like everyone else, we instinctively headed for water. Countless people perished in rivers and canals that night.

Making our way through burning buildings that looked like they might collapse at any moment, we eventually reached a small park near Shirahige Bridge. By now we had no strength left, but then we noticed that the night sky was turning white and dawn was breaking. Our faces were black with soot. The fingers of my gloves were burned off and only the cloth on the backs of my hands remained. The handcart my father had been pulling and our luggage had vanished. Gone too was the pouch of old coins I had tied to my belt. Shocked that I had lost my only treasure, I wanted to retrace my steps to look for it but my father stopped me. As he took a long piss against a tree, I noticed his bamboo water gun was still on his back. Exhausted and bewildered, my mother and sisters just gazed at the sun as it rose in the eastern sky.

The fires started to die down at about five o’clock in the morning. Dawn broke at six. The fierce wind had finally abated a few hours earlier. Like a clot of blood the sun rose unsteadily in the east, yet the sky remained strangely dark.

My parents, sisters and I had managed to escape to a corner of a park near Shirahige Bridge. After my mother treated the burns on my hands with the ointment from my emergency bag, I went on my own to the foot of the bridge just a couple of minutes away. The Kubota Ironworks, where I had been working just the day before, was near the bridge facing the Sumida River. What had become of the factory and my classmates and teachers who worked there?

In just one night the ironworks had been reduced to skin and bones. The skin was tin plate and the bones were iron frames. The cranes were bent like sticks and foul-smelling black smoke was billowing up from the hollowed-out blast furnace. It was deathly quiet, except for the sound of a sheet of paper attached to the gate fluttering in the breeze. I read the handwritten message.

To All Factory Staff

Don’t be discouraged by a little thing like this!

Let’s rebuild our factory right away.

Keep fighting! The enemy is desperate too!

Child though I was, I felt a kind of emptiness as I gazed at those words. Was the enemy really as desperate as we were? I continued walking to the bridge. From the river I heard men’s voices shouting “One, two, three, heave!” When I got to the quay of the Sumida River, I could only stare in horror. On the stone wall of the smoldering quay were several civil defense corpsmen in khaki uniforms with cloths wrapped over their heads and tied under their chins. From a gap where the wall had collapsed they made their way backward and forward over the logs on the water’s surface. Shouting instructions to each other, they were pulling dead bodies out of the water. Looking down, I saw that the river was full of burned and drowned corpses. The men were reeling in the bodies with hooked poles. They bound the stiff corpses with ropes, hauled them up onto the quay, and laid them down in rows like tuna at a fish market. Then I noticed that my father was standing behind me. ‘Take a good look, Katsumoto,’ he said. “Look and never forget. This is what war is.” I clearly remember the way he spoke, muttering the words under his breath. Exhausted by his struggles and privations, he died shortly after the war ended. The frightful scene we witnessed in the Sumida River and my father’s despairing voice have always stayed with me.

|

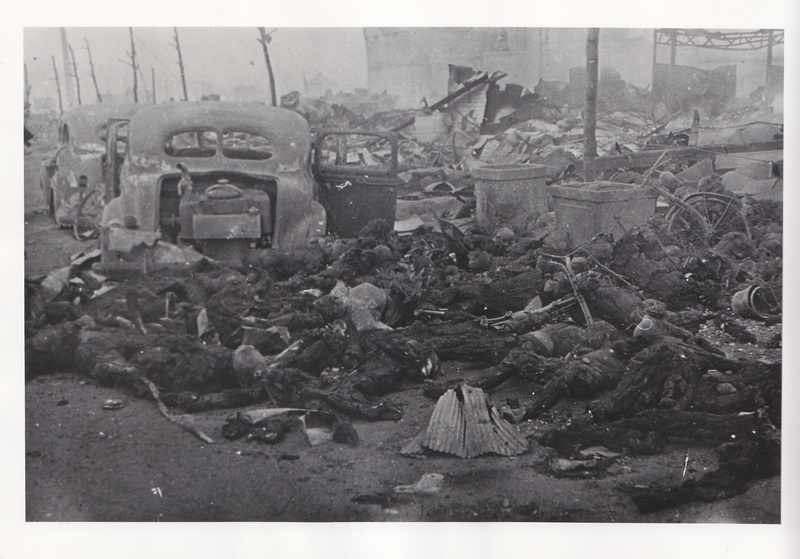

Bodies being pulled out of the canal near Kikukawa Bridge Photograph by Ishikawa Koyo Source: U.S. National Archives |

My father and I walked back together through the smoldering ruins. An indescribable stench filled the air. Sheets of burned tin plate were scattered over the road and tangled telephone lines drooped limply from scorched telegraph poles, swaying over our heads in the wind and blocking our way like barbed wire. From the iron-barred windows of warehouses, melted glass hung down like icicles. On the road were countless six-sided holes where incendiary bombs had fallen and pierced the ground, and amid the smoldering debris water spurted up from a broken pipe. For some reason, the bright white of the toilet bowl lying near it was particularly striking.

The whole area was pervaded by such a sickening stench that we had to open our mouths and breathe in gasps. The ruins were crowded with victims like us. With scorched faces and bloodshot eyes, many of them could hardly see. There was an endless stream of refugees from the fires – people using their leggings as bandages, people with burned cheeks, split lips and mouths hanging open, people with handcarts and bicycle carts carrying burned futons and clothes soaked in water. We too were part of this procession of ghosts. “Make way, make way!” shouted a group of men in steel helmets coming from in front of us, roughly pushing people aside. They were carrying a stretcher made of iron pipes and tin sheet. On it was a half-naked corpse covered with glistening grease. One arm was stretched out diagonally, grasping at nothing. I shuddered and covered my mouth. My mother turned her head away. Everything we saw that morning was grotesque.

We turned into a side street and walked through Mukojima-Hyakkaen Gardens. This was a scenic spot well known in Tokyo for its flowers blooming all year round, but now the branches of the trees were all burned black and covered with futons and clothes. When we reached the Terajima crossroads, we saw something quite unexpected. Only the buildings at the corner where we lived were still standing. What a stroke of luck! The schools, factories, cinema, and fire station were all gone. All around us were burned out ruins and reddish brown scorched earth. Just one row of buildings including our house had been left untouched. “Look, there’s our house!” cried my mother, and we all ran towards it. When we opened the front door, we heard the feeble meowing of Tomi, our tortoise-shell cat, who ran up to us and snuggled against our legs.

But our neighbors Mrs. Torii and her son would never return. We had encountered them during our escape with futons wrapped around them and wooden clogs hanging from their waists, looking rather like the comic book character Tank Tankuro. What had become of them? The watchmaker’s store where they lived had also been undamaged by the fires. From outside we could hear the ticking of the wall clock and cuckoo clock, keeping the time like living beings. Thinking they might have returned, I peered into the store. At the sight of the pendulums swinging back and forth, I suddenly felt afraid and returned to our house. Although they had the foresight to take all those clogs with them so that they could walk back over the scorched ground, Mrs. Torii and her son Iwao had perished in the inferno.

Testimony of Ishikawa Koyo

The only person to photograph the damage in the immediate aftermath of the Great Tokyo Air Raid was the Metropolitan Police Department photographer, Ishikawa Koyo.1 In order to make a photographic record, Ishikawa was instructed by Chief of Police Saka Nobuyoshi to go to all the districts under the Department’s jurisdiction and take photographs just after the air raid started.

From the roof of the Metropolitan Police Department headquarters, Ishikawa saw the night sky in the east turn bright red as the whole Shitamachi was engulfed in a sea of fire. He ran down the stairs to the air defense headquarters in the basement and gazed at the large map of the Metropolitan district on the wall. On its surface countless red and blue miniature lamps were lit, enabling him to see at a glance that vast numbers of incendiary bombs had been dropped in Honjo, Fukagawa and Asakusa wards. Gulping involuntarily as he realized that tonight’s work would put him in danger of his life, he steeled himself and reported to Chief Superintendent Hara that he was going directly to the stricken area. Ishikawa loaded his beloved Leica camera with Kodak film and started the engine of his Chevrolet, which had threaded its way through the burning city several times before. It is ironic that the photographer of the Tokyo Metropolitan Police Department drove a Chevrolet and used a Leica camera with Kodak film. Ishikawa laughs as he recalls that he didn’t have any Japanese-made equipment. In the private diary he scrupulously kept throughout the war, he recorded what he saw that night.

|

Ishikawa Koyo |

“As I was driving at full speed along Showa Road, fire trucks and police security patrol vehicles overtook me, their sirens wailing. When I got to the Asakusabashi crossroads, I was confronted with a gruesome spectacle – a conflagration of raging flames swirling in the wind. At Ryogoku Bridge, I saw an endless stream of escaping people coming towards me over the bridge from the other side. The congestion and confusion defy description. A policeman was shouting in a shrill voice as he tried to guide the crowds, women were screaming, and civil defense corpsmen were barking instructions. A pedestrian could hardly make any headway, let alone a car. I eventually managed to get the car to the side of the police box at the bottom of the bridge and asked a policeman to take care of it. Hanging my camera on my shoulder, I crossed Ryogoku Bridge, slowly forcing my way through the surging mass of people coming from the opposite direction. I was relieved when I finally made it to the bottom of the stairway at the entrance of Ryogoku Police Station, but the area was surrounded by a wall of raging fires. The hot wind was blowing so relentlessly that I couldn’t open my eyes. Looking up at the sky, I saw the crimson flames reflected on the huge silver fuselages of the enemy B-29s above as they cruised at low altitude. As if that wasn’t enough, they were still dropping countless bundles of incendiary bombs.

“In the police chief’s office, a messenger was reporting the current situation. The lights in the police station had gone out but it was still bright in the light of the swirling flames outside. The messenger reporting to the chief had clearly had a rough time getting there. His uniform was in tatters, his face was scorched black, and his eyes were bloodshot. Their faces reflected in the flames, the policemen looked like red demons as they ran about in utter confusion. The police chief looked at me and said, ‘There’s nothing more you can do here. Get away as fast as you can.’ I told him to take care and left the building, but the raging fires and fierce wind bore down on me. I was too preoccupied with getting out of there alive to think about taking photographs.

“Whichever way I looked it was a sea of fire. I found a place a little less exposed to the wind, crouched down and crawled along the road. As the conflagration burned ever more fiercely it whipped up strong winds which stoked the flames, burning people alive as they frantically tried to escape. I saw several people fall and die helplessly in front of me, but there was nothing I could do for them. Their bodies rolled along the road like sacks of potatoes in the stream of fire, passing by with a strange howling sound. Countless futons and other belongings turned into balls of flame as they were swept along in the torrent of fire. I saw the raging flames gutting a building, leaving just the roof intact. As the blizzard of sparks and embers blew down over me, I wondered how long I could last. I was already prepared for death.

“But to die there like that without a struggle was just intolerable. I could have just closed my eyes and accepted my fate, but I told myself I must not die. In that deadly whirlwind of flames, my police colleagues were still making desperate efforts to save as many people as they could under this fierce attack by the barbaric enemy. If they were determined to beat the odds, I too must fight to survive rather than just sitting here waiting for death. Boiling with rage, I got up and found shelter behind a collapsed stone wall from the smoke and blasts of hot air that were scorching my face and burning my eyes.

“In the sky above, as if they were mocking us, the B-29s were still flying serenely through the black smoke at such low altitude that it seemed you could hold out your hand and touch them. As they descended to drop their bombs again and again, the fires on the ground were reflected on their bodies. With the bright-red flames flickering on their huge fuselages and four engines, they looked like winged demons from hell. In my fury at being unable to grab them and throw them to the ground, I yelled ‘You bastards!’ but no sound came from my mouth.

“I don’t remember where or how far I crawled after that. The fires were still burning furiously and the sky was crimson when I noticed that the enemy planes had gone. Through the smoke, I saw that the sky was suffused with a pale light. At that moment I knew at last that I was in the land of the living. There were several other survivors around me. I couldn’t help weeping at the sight of them. I was not sad but overjoyed that they had managed to live through the inferno. Their faces were scorched black, their hair and eyebrows burned, their eyes inflamed by the smoke and ashes, and their wrists swollen dark red by burns. Their clothes were in shreds and covered with holes made by the sparks. I was in the same state. My throat was parched and I did not even have the energy to speak, but I pulled myself together and made my way to the scorching hot road where fires were still burning furiously.

“All along the tramway, the overhead wires were hanging down like spiders’ webs, and the iron frames of burned-out trams looked like huge birdcages. The road was covered with abandoned household goods, bicycles, and carts, all burned and scattered about. The charred bodies of the dead – it was impossible to tell whether they were men or women – lay scattered everywhere. In a corner that people apparently thought offered shelter from the flames, the victims had fallen on top of one another to form a mountain of corpses.

“A hand pump used by the neighborhood association lay burned on the ground, its nozzle still pointing towards the fires – a poignant testimony to citizens’ gallant but hopeless firefighting efforts. Dragging my heavy legs, I staggered through Kikukawa, Morishita-cho and Komagata, forcing my blinded eyes open to witness the devastation around me. I took photographs of the charred bodies on the roads, bodies of women and children, and bodies piled up in heaps. As I pointed my mud-covered Leica at the corpses of all those people who had died in deep resentment, I imagined I heard an invisible voice rebuking me from above. My hands trembled and I could only press the shutter button weakly. But as long as I was alive, I had to keep taking those photographs to fulfill my mission, and to do that I had to be hard-hearted. When I had finished my work, I put my hands together in prayer for the victims and went on my way.”

|

Bodies in Ishihara-cho, Honjo ward Photograph by Ishikawa Koyo Source: U.S. National Archives |

After his narrow escape from the conflagration near Ryogoku Police Station, Ishikawa Koyo returned on foot to the Metropolitan Police Department Headquarters at around noon. His beloved Chevrolet had been gutted in the inferno. That same afternoon he took his camera and accompanied the security squad chief on an inspection of the Honjo district. They arrived at Suzaki Police Station at about 3.00pm. According to Ishikawa, the body of Police Chief Tanisue, a close acquaintance who often looked in at the police headquarters photograph room, was found “in a mummified state,” sitting in his chair in his office holding his child in his arms. Only the iron frames of the chair remained. The official history of the Metropolitan Police Department provides a record of his heroic last moments: “The police chief first ordered his staff to release all persons in custody and to remove important documents, then continued to give various instructions. At just past two in the morning, they attempted to extinguish the fires, but the entire building became engulfed in flames and they were all trapped inside. After the conflagration died down, the bodies of the staff including Police Chief Tanisue were found in the ruins of the police station.”

1 At the time of writing, only Ishikawa’s photographs were known to the author. Photographs taken by three other photographers – Kikuchi Shunkichi, Hayashi Shigeo, and Fukao Kozo – were later discovered. All of these photographs are included in a 520-page collection Tokyo Kushu Shashinshu (Photographs of the Tokyo Air Raids) published in January 2015.

Testimony of Hashimoto Yoshiko

Among those who were in the Shitamachi district of Tokyo on the night of March 9 was Hashimoto Yoshiko, a young twenty-four year-old mother. Yoshiko was at home in Kamezawa, Honjo ward, relaxing with her feet under the kotatsu, a low wooden table covered with a futon and heated from underneath. She gazed fondly at the face of her baby son Hiroshi as he slept peacefully beside her. He had been born on January 3, 1944, and was now 13 months old. Although it was a time when milk and food were in short supply, Hiroshi had graduated from crawling and could now stand and walk. Had it not been for the war, this would have been the proudest and happiest time for a mother.

When Yoshiko married, her husband Bunsaku was “adopted” by the family and took the family name, a common practice back then in families without male heirs. Bunsaku had run the family knitwear store, but the business had been combined into a trust during the war and now he worked at a factory. But he could never be at home when he was really needed. Apart from his work, he was often summoned to conduct civil defense duties such as demolishing the houses of citizens who had been forced to evacuate to make space for firebreaks. When the air raid alert siren sounded, Bunsaku had to leave the house to guard the air-raid defense post at Yanagishima Elementary School.

On March 9, Bunsaku went out immediately when the siren rang, leaving behind Yoshiko with her parents and three younger sisters. Carrying the burden of being the eldest daughter and heir, Yoshiko often felt suffocated by the love of her mother Yasuko, but it was probably just her youth that made it hard for her to get along with her mother. Now she regrets this deeply.

On that night of March 9 when the family spent their last moments together, Yoshiko recalls that for some unknown reason the lights in the house suddenly went out. Under the blackout regulations during the war, the lights were all naked bulbs covered by black cloth so that they could not be seen outside. Yoshiko has no way of knowing now whether the power failure was just in her house or the whole neighborhood. But she remembers she felt a strange foreboding and got up from the kotatsu.

“What happened?” said her sister Chieko, who had managed to find a candle and light it with a match.

“I don’t know. Maybe a bomb dropped somewhere,” replied Yoshiko.

“But they said the enemy planes had gone away.”

“Yes, it’s strange.”

In the light of the candle, they all had gloomy expressions on their faces that were quite different from how they had looked under the electric lights. Even now Yoshiko cannot forget the lonely and anxious look on her mother’s face. Shortly afterwards, the incendiary bombs started raining down on Tokyo.

|

The Hashimoto family Top, left to right: Chieko, mother, Yoshiko Bottom, left to right: Father, Hisae, Etsuko Courtesy of Hashimoto Yoshiko |

“When the air raid started, we all went down into the family air raid shelter. We had already experienced many air raids and had always waited them out in the shelter, huddled together and holding our breath. We never thought about escaping. There were seven of us in the shelter – my parents, my baby and I, and my three younger sisters.

“The roar of the B-29s’ engines was deafening and now and again we heard the dull thuds of bombs falling all around us. This time it was much worse than usual. I cowered in a corner of the shelter, holding my baby son Hiroshi tight and praying that it would soon be over. ‘We have to get out of here!’ shouted my father, who had gone to look outside. I didn’t have time to look at my watch, but I think it was still before one in the morning. ‘We can’t stay here any longer. If we don’t escape, we’ve had it!’ When I heard my father say that, I knew the moment we’d all dreaded had come at last. And the timing couldn’t have been worse with that fierce north wind blowing so strong it might even blow away a small child. Outside the shelter, it was just as my father said. The B-29s were flying freely overhead and to the north of our house was so bright it looked like broad daylight. It wasn’t just to the north. The conflagration had spread over a wide area all around us, scorching the sky bright red. The swirling sparks made it hard for us to keep our eyes open. Raining down across the sky, the sparks and embers fell sputtering onto roofs and wooden balconies.

“I hurriedly strapped Hiroshi to my back and covered him with two short coats. If one was burned off, I hoped that the other would protect him. Then the seven of us headed south. My father pulled the handcart loaded with our most precious possessions, while my sister Etsuko carried a cooking pot containing rice and my mother a kettle filled with water. My father knew from his experience of the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923 that the things we would miss most were water and food, so we made a point of taking them with us.

“Chased by the fires, we ran first to the road under the tracks of the Sobu Line. The area on both sides of the overhead railway had been cleared after compulsory evacuation to create a firebreak. There were several large water tanks set up by the neighborhood volunteer labor corps and they were all filled to the brim with water. We all felt relieved to get there, but that didn’t last long. The flames were bearing down on us, rolling along the road and leaping up into the air. Seeing this, the crowd that had gathered near the water tanks started to scatter in panic. At that moment, we disagreed about what to do next. ‘It’s no good staying here. The B-29s are certain to target the railway. We’ve got to escape to the canal,’ said my father. Chieko thought we should stay where we were: ‘There’s water here, and we can always get into a water tank if it gets really bad.’ But my father was insistent: ‘While we’re arguing about that the incendiary bombs will come raining down on us. If we’re going to escape, we’ve got to do it now.’ Deferring to my father’s opinion, we abandoned the cart and our belongings and headed for the Tatekawa canal. We thought that being near to water would be safer than the railway, and that was the nearest waterway. However much Chieko insisted on staying there, we assumed she would follow us.

“Although it was only about five hundred meters from there to the Tatekawa canal, by that time fires were raging all around us and the houses facing the road were engulfed in flames. With all the smoke and hot air as the fires spread, it felt as if my body was floating. Tile roofs flew up and shafts of flames shot up from under them. When we got to Mitsume Street, we noticed that we’d not just become separated from Chieko but from Etsuko as well. In the middle of the escaping crowds and pursued by flying sparks, my parents and I were doing our utmost to avoid losing sight of each other. If we’d fallen, we would have been trampled to death by the people running behind us. As we were running beside the canal, the strap on one of my wooden clogs broke. My father was also in great pain from the gangrene in his legs, so we immediately turned right and got onto Sanno Bridge.

“On the other side of the canal, Tatekawa-cho was also in flames, so we had no choice but to crouch down on top of the bridge. This place, where the matchmaking deity Gentoku was said to reside, was full of childhood memories. There were rows of night stalls along both sides of the canal and we children would excitedly explore them in the light of the carbide lamps. At first the only purpose of the canal was to drain the land, but later it was used as a waterway connecting the Sumida and Naka rivers. Sanno (“third”) Bridge was one of several bridges over the Tatekawa canal starting with Ichino (“first”) Bridge. On festival days, as well as the various stalls, boats lit by red lanterns would float along the canal. It was once a place filled with the traditional Shitamachi atmosphere, but now fires were raging on both banks and people’s belongings floating on the water were lit by flames.

“Whipped up by the fierce wind, sparks and embers from the raging fires over the canal and in the houses on the banks blew over the bridge and attached themselves to people’s shoulders and backs, setting their clothes on fire. At first we watched out for each other and smothered the sparks, but soon we too were catching fire, putting them out, and catching fire again. People were turning into balls of flame and rolling around on the ground. The ones whose hair caught fire screamed and thrashed about wildly. I heard my baby Hiroshi let out a strange cry, so I hurriedly unstrapped him from my back and held him up to see what was the matter. His mouth was glowing red, but it wasn’t blood. While he was crying sparks had flown into his mouth and were burning in his throat. In a panic, I pried them out with my finger. Then my mother covered my little sister Hisae and me with two coats and lay on top of us, but the coats quickly caught fire and she threw them into the canal below. My eyelashes melted off and my hair burned with a sizzling noise. It didn’t feel hot but it was quite painful. My mother got on top of us and my father lay on top of her. We were all curled up like a snail, desperately trying to protect each other. At that moment I thought, ‘So this is how I’m going to die – here on this bridge with my baby who’s only just started to walk.’ I closed my eyes and saw the flickering red flames behind my eyelids. ‘Yoshiko, jump into the canal!’ screamed my father as if he’d suddenly gone crazy. Holding my shoulders and pulling me to my feet, my mother shouted, ‘Yoshiko, take this!’ She took off her air-raid hood and put it on my head. As the eldest daughter I had always sulked and defied my mother, and now she was giving me her own hood to wear. As long as I live, I’ll never forget the sight of my mother’s face with all those flames behind her.

“Feeling that I had become a burden to my parents, I climbed over the railing of the bridge and jumped into the canal holding my baby close to me. The freezing water pierced through me like a knife. At first I sank deep into the water, but I was a strong swimmer. Kicking the water, I quickly rose to the surface together with Hiroshi. The current was strong but luckily a raft floated up to me and I grabbed it, put my baby on top of it and held onto it as we were carried downstream. Perhaps because of the shock, Hiroshi’s eyes were wide open. As the raft floated along I looked up at Sanno Bridge. The flames were leaping like living creatures among the terrified crowds with a tremendous roaring sound. But I couldn’t see my mother or father up there. Later I wondered whether they had heart failure when they entered the freezing water, or perhaps people had jumped in the canal on top of them and they had been unable to rise to the surface. In the water underneath the bridge, people huddled together under a sheet of burned tinplate were frantically chanting sutras.

“On the other side of the canal the fires were raging and crackling as they devoured the buildings on the bank. Sparks from the fires fell over the raft and water sprayed up from the surface here and there. I had run out of strength and thought I’d had it, but when I saw the face of my baby on the raft I forced myself to keep going. After the raft had floated a little further downstream, a small boat with two men in it approached us. ‘Help! Help! Please at least save my baby!’ I shouted. One of the men picked up Hiroshi and put him in the boat and then pulled me out of the water.

“The next bridge was Kikuhana Bridge. Now it’s an iron bridge but back then it was made of wood. The arched bridge was engulfed in bright red flames from end to end and this was reflected as a ring of fire on the surface of the water. As I was looking at this in horror, a dark figure leapt from the bridge into the canal and spray rose up. When we passed through that ring of fire, I thought it really was the end. If the bridge had fallen on top of us, it would have been. Hugging Hiroshi tightly, I curled up at the bottom of the boat and prayed. Then I noticed that the ring of fire was behind us and the boats and rafts had stopped moving. The direction of the wind must have changed. All around us I could hear people in the water groaning in pain. I put my hand out to help them, but they didn’t even have the strength to cling to it. If they had got hold of my hand, they might have pulled me down into the water. The margin between life and death was that slim.

“Eventually a dim light appeared through the smoke and though I was still barely able to see or think, I noticed a little girl floating in the water. She must have been about four years old. I weakly held out my hand saying, ‘Hold on to this,’ but when I looked more closely I saw that she was dead with her face down. The red waistband around her monpe trousers was trailing behind her in the water. Instinctively I hugged Hiroshi tight and called out his name, but his lips only quivered slightly.

“It’s very hard for me to talk about this. I always seem to get incoherent at this point. I’m a very stubborn person and I don’t usually cry, but when I talk about the night of March 9 … Could I take a short break here?”

Yoshiko finally saw the sun rise on the bank at the crossing between the Tatekawa and Oyokogawa canals. She gave a start when she heard one of the men on the bank say “How’s the baby on your back? Take a good look!” Looking around her, she saw several mothers with babies on their backs and short coats covering them. They must have escaped on rafts or clung to timber in the canal, but in their desperate efforts to escape from the fires they had no time to look round at their babies. Many of the young mothers had finally reached dry land only to find that their babies were dead, and now they lay exhausted and weeping on the bank. Most had strapped their babies to their backs to free both their hands and had not noticed the sparks burning through the coats covering them. By the time they turned round to look, it was too late.

|

Bodies of mother and child Photograph by Ishikawa Koyo Source: U.S. National Archives |

Yoshiko had miraculously survived while holding her baby to her chest. Somehow she had managed to keep hold of Hiroshi after she leapt into the canal. If she hadn’t needed to protect him, she might have given up the ghost herself. But having survived by the skin of her teeth, Yoshiko had exhausted all her strength and could not even get to her feet. The two men who had pulled them out of the river put Yoshiko and Hiroshi in a cart they found in the ruins. The burned-out cart had no tires. When Yoshiko heard its wheels rattling as they went along, she realized that she was still alive.

Yoshiko fell off the cart several times. “Every time I fell, I couldn’t get back up again, so I just lay there on the ground holding onto my baby,” she recalled. “I could no longer move my limbs. But those men were very kind. One of them ran a rice store nearby and the other worked at Honjo Post Office. Every time I fell off the cart, they said ‘Oh dear, missus, there you go again,’ picked me up and put me back in the cart. Only its iron frames were left, so it was quite a rough ride and my bottom hurt, but I held Hiroshi tight with one hand and clung on to the charred iron frame with the other. We were passing through the town where I’d grown up. There were dead bodies all around us, but my vision had become blurred and fortunately I could hardly see anything. Thick smoke hung over us and swirled in the wind. The town seemed strangely small – perhaps a place always looks like that when everything burns down. Above us in the sky, I saw the yellowish sun rising. The sun was rising just as it always did, but my parents and younger sister were gone forever.”

Yoshiko was taken to Doai Hospital where she received first-aid treatment. Her eyesight eventually recovered. Her baby was given a camphor injection and started to get better, but he had forgotten how to walk and excreted jet-black stools. They stayed one night at the hospital so that they could monitor Hiroshi’s condition. Yoshiko had an almost irresistible urge to steal the blanket they gave her at the hospital. She had lost her home and no longer had a futon or even clothes to wear. She really wanted that blanket for the baby, but she realized it would be needed by mothers and babies in even worse condition and left it at the hospital.

The next day Yoshiko’s husband Bunsaku, who had been on air-raid defense duty at Yanagishima Elementary School, came to the hospital. “You’re alive!” he exclaimed in amazement and joy. Her next visitor was her little sister Hisae, her face covered with burns. Chieko had miraculously survived unhurt by the water tanks under the tracks of the Sobu railway line, but both of her parents and sister Etsuko, who had been carrying a cooking pot full of rice, would never return.

In the air raid of March 10, 1945, Hashimoto Yoshiko lost her father Sojiro, mother Yasuko, and younger sister Etsuko.

Testimony of Kokubo Takako

On the night of March 9, nineteen year-old Kokubo Takako, who worked at the Fukagawa ration distribution volunteer corps headquarters, was at the home of her friend Koike Yasue. Takako’s home was in Hirai-cho, but that night she was visiting her friend in Toyosumi-cho on the other side of the canal. Because of her husband’s work, Yasue lived in an official residence of the Imperial Household Department’s Bureau of Forestry. Since her husband went to fight in the war, she had been living there alone with her four year-old son Noboru. Yasue complained of feeling lonely and Takako often went over to cheer her up. Yasue had an open-hearted nature and enjoyed certain privileges living in a residence of the Imperial Household Department, including her own bath and relatively generous rations. Living nearby, Takako went to visit her friend whenever she could. Their greatest pleasure was to sit opposite each other and chat under the warm kotatsu. Even when Takako stayed over at Yasue’s place, her mother didn’t seem to mind.

That night, Takako was able to relax for the first time in a while, enjoying a leisurely bath and feeling quite refreshed. As she got out of the bath and hung the towel on the wall, she felt as if it was suddenly peacetime again. She got back under the kotatsu and continued chatting with her friend, but the strong north wind rattling the shutters made her anxious.

“What a wind! Wouldn’t it be awful if they came tonight,” said Takako. Yasue frowned. She reached out and adjusted the coverlet on little Noboru’s futon. “It’s a horrible wind. Now you’ve made me feel chilly all of a sudden,” she said with a shudder.