The trilateral summit among the presidents of Mongolia, China, and Russia, on the sidelines of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) at Dushanbe, Tajikistan on September 11, 2014, was the culmination of a deliberate summer whirlwind policy blitz of Mongolian President Tsakhia Elbegdorj to position his country to take advantage of deepening Sino-Russian economic relations. Concerned that a “great game” to create a new version of the Eurasian Silk Road was being played out without any Mongolian input, Mongolia’s activist president used the celebrations around the commemoration of different anniversaries in Sino-Mongol and Mongol-Russian relations to make certain that his two powerful neighbors did not proceed with transportation and energy cooperation without taking into account the role of a mineral-rich Mongolia. The landlocked Northeast Asian nation is seeking to become an international transportation hub and at the same time diversify its mineral exports. This spotlight trilateral summit moment in Mongolian-Chinese-Russian relations, together with the trips of Chinese President Xi Jinping and Russian President Vladimir Putin to Mongolia a few weeks previous, attracted attention, bordering on concern, of other Eurasian countries, the European Union, and the United States who do not fully comprehend Mongolia’s strategy.

|

A Spring and Summer of Bilateral Summits in Shanghai and Ulaanbaatar

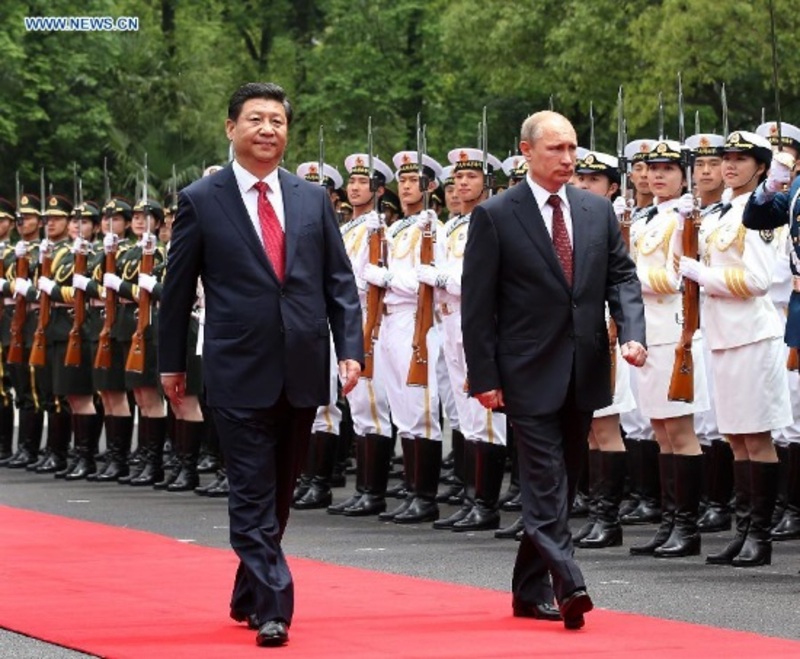

The Dushanbe summit came at a time when both China and Russia have serious foreign policy challenges in their home regions—China in the South China and East China seas involving clashes with Japan, the Philippines and Vietnam among others, and Russia in Ukraine resulting in increasingly crippling economic sanctions. Mongolia, for its part, has had a precipitous decline of over 62% in foreign direct investment (FDI) and reduction of its growth rate to 5.3% (one-half of 2013’s 11.8%) in the first half of 2014.1 This was connected to concern over Mongolia’s vacillating investment legal regime and a slowdown in sales of coal to China. All of these factors propelled increased cooperation among the three nations in the first half of 2014—initially seen via a series of bilateral meetings. The first example was the planning among the leaders when they were in Shanghai on May 20, 2014 at the Fourth Summit of the Conference on Interaction and Confidence Building Measures in Asia over the timing of the Xi and Putin visits to Mongolia. President Xi had agreed to go to Ulaanbaatar to celebrate 65 years of Sino-Mongolian diplomatic relations and announce a new push towards energizing China’s strategic partnership with Mongolia. Putin’s Mongolian visit, ostensibly to celebrate the 75th anniversary of the Soviet-Mongol victory over an invading Japanese army in 1939 at Khalkhin Gol (Nomonhan), was aimed at jumpstarting Russian’s morbid economic relations with its former Cold War satellite whose trade and investment picture has been monopolized for over a decade by China. Originally it seems that Xi and Putin mulled over the possibility of holding a trilateral gathering in Ulaanbaatar in August, but this timetable ultimately was rejected because Putin decided to squeeze in a 5 hour visit to Mongolia instead on September 3rd as part of a swing through the Russian Far East. Mongolian officials told this writer they believe that while Putin was in Shanghai, he also agreed to not oppose Chinese proposals for deeper investment and economic ties with Mongolia in exchange for China’s support for Russian plans on modernizing and developing rail links with Mongolia.2

|

Xi Jinping (left) and Vladimir Putin in China |

Mongolia hosted Chinese President Xi’s state visit on August 21-22. Mongolian leaders deemed the visit very successful in signaling Chinese recognition of the value of stronger political and economic ties to Mongolia, as well as for Chinese acquiescence to Mongolia’s desire to develop trilateral cooperation among China, Russia and Mongolia on a shared vision for a new Silk Road economic corridor. The Chinese signed 26 documents with the Mongols, and Xi’s personal offer, in his address to the Mongolian parliament which was broadcast live on both Mongolian and Chinese television, for the Mongols to participate in his “China Dream” initiative was seen in Mongolia as a positive gesture by the government and domestic press. However, Mongolian blogs resonated with nervous chatter about Chinese hegemonic ambitions fueled by Xi’s strange recital of a famous Mongolian nationalist poem in which he called Mongolia his “native land.”3

Mongolia and China signed a Joint Declaration on relations that set a bilateral trade target of $10 billion by 2020 (up from $6.2 billion in 2013) under a “three-in-one” cooperation model, integrating mineral exports, infrastructure construction and financial cooperation. The Chinese side promised to provide Mongolia 1.3 billion RMB [US$260 million] of aid within 3 years for major economic projects and to possibly grant a soft loan in the amount of RMB 1 billion [$162.7 million]. The presidents of Mongol Bank and Chinese National Bank agreed to an increase of the currency swap exchange from 10 billion to 15 billion RMB to provide foreign currency to Mongolia’s domestic market.

The five new transportation agreements may prove the most significant of all in that they relate to the future of Eurasian economic integration and Sino-Russo-Mongolian cooperation on regional rail projects. These were 1) Inter-Governmental Agreement on “access to the seaport and transit transport” 2) Inter-Governmental General Agreement on development of cooperation of the railway transit transport 3) Inter-Governmental MOU on Development of Railway Cooperation 4) MOU between Ministry of Road and Transportation of Mongolia and Railway Authority of People’s Republic of China on renewal of the “Mongolia and China Border Railway Agreement” and 5) Agreement on “Mongolia-China Border Port Management Cooperation Commission” between National Council of Border Port of Mongolia and General Customs Office of People’s Republic of China. The latter document designated six Chinese seaports, including Tianjin, Dalian, and Jinzhou, for the transit of Mongolian exports to overseas markets. A key breakthrough for the landlocked Mongolia was the agreement that two-thirds of Mongolian goods transported on Chinese rails would be destined for the Chinese market while one-third would be for export via Chinese seaports to third countries. Border crossing co-operation and access to rail capacity within China were promised, and four new Mongolian ports (Shiveekhuren, Bichigt, Gashuunsukhait and Nomrog) were opened for rail transport. New tariffs and additional volume for Mongolian cargo on Chinese railroads were established, and China also gave Mongolia a 40% discount on current transportation tariffs. The big catch to all of these agreements is the necessity to secure ratification by the Mongolian parliament, which remains divided on new rail links to China and which size rail gauge to use.

|

Mongolian President Tsakhia Elbegdorj (right) and Xi Jinping |

Not two weeks later the Mongols welcomed Russian President Putin’s visit as visual proof of a new era in Russian economic investment in Mongolia to balance nearly total Chinese monopolization (89% in 2013) of Mongolia’s foreign trade. The 14 bilateral agreements signed were vaguer than those with China, but of greater importance was Putin’s political message that Russia had not forgotten Mongolia. What is most interesting about the rail projects covered in the Russo-Mongolian agreements is the potential impact on Sino-Russian rail cooperation. An example is the electrification and construction of a second track for the 1100 km (684 mile) rail from Mongolia’s northern border with Russia through the planned Sainshand minerals processing industrial zone in the Gobi to Zamyn Uud on the Chinese border. Russo-Mongolian cooperation also covered exploring development of a western Mongolian railway line joining Russia and China for Russian exports to China, India and Pakistan, as well as researching utilizing the 230 km (143 miles) Choibalsan–Erentsav eastern railway for transit goods into northeast China. During the press conference that Putin held at the end of the Mongolian visit, he singled out bilateral transport cooperation: “This is a very important sector for Mongolia, and it is in our interests too to increase Mongolia’s transit potential. Mongolia is located between Russia and China after all. We are big trade and economic partners and have bilateral trade with China that will come to $64 or already $65-67 billion this year. It therefore makes sense to put Mongolia’s transport possibilities to greater use than is the case today.”4

Dushanbe Trilateral Summit

The Mongols in the spring had begun to talk publicly about a trilateral summit meeting taking place in Ulaanbaatar. When it finally occurred in Dushanbe, President Elbegdorj particularly hailed the meeting as a historically significant first in the history of the three countries5 and suggested it take place every three years in Mongolia. Both Xi and Putin expressed their general interest but did not confirm the venue and timing. President Xi proclaimed that the trilateral summit was of “great significance to deepening mutual trust among the three parties, and pushing forward regional cooperation in Northeast Asia.”6 He said that his Silk Road Economic Belt initiative meshed well with Russia’s transcontinental rail plans and Mongolia’s desire to build up a China-Mongolia-Russia economic corridor in its Talyn Zam [Steppe Road] program. However, he cautioned that if this concept were to succeed, the three nations needed to strengthen traffic interconnectivity, facilitate cargo clearance and transportation, and build a transnational power grid.7 As for Putin, he noted that: “Things discussed at this meeting create the appropriate mechanism to discuss and resolve the largest projects to be implemented by us in the future, and we agreed to promote our cooperation in this regard.” Moreover, the Russian leader asserted that the geographic proximity of Mongolia, Russia and China facilitated long-term projects in infrastructure, energy and mining: “We have things to discuss and we find it important, feasible and useful to establish a regular dialogue.”8

Many foreign observers saw the Dushanbe meeting as proof of China and Russia’s deepening coordination, especially regarding Mongolia and the greater Eurasian continent. However, equally discussed was the concern of Mongolia’s “third neighbors” about the real intentions of President Elbegdorj. Despite the strong democratic record of Elbegdorj from his days in the streets as one of the key protest leaders who brought down Mongolia’s communist government in 1990 and the fact that the plethora of agreements with both China and Russia to improve Eurasian transportation connections through Mongolia also should help Turkey, Europe, Japan and South Korea to become stronger regional trade partners, Mongolia’s new strategy has caught many, including in the restless foreign investor community, off guard. When a Mongolian delegation visited New York and Washington in connection with President Elbegdorj’s speech to the United Nations General Assembly in late September, its members were met with a barrage of questions from American officials about the future of Mongolian allegiance to its policy of reaching beyond its two border neighbors to integrate into the world economy (the so-called ‘third neighbor policy’), as if Mongolia were returning to a pre-democratic mentality.

This concern, while understandable, arises from a lack of understanding of Mongolia’s overall trade predicament and its limited options to find a way forward. After 20 years of unsuccessful efforts to find new trade partners other than its two border neighbors for its minerals and animal by-products, Mongols of all political persuasions came to recognize that they cannot ameliorate the Chinese monopoly over their economy without careful development of real transport and pipeline alternatives to their present poor infrastructure. Following World Bank and IMF advice to just build new roads and rail spurs south to service the Chinese market would merely perpetuate the dependence on China, yet it may be necessary in the short- and mid-term to keep the economy afloat. A longer term strategy of reviving Russian economic investment in Mongolia and building transport infrastructure north to link with the Trans-Siberian rail system as well as promoting Mongolia as a reliable and cheaper alternative for Sino-Russian transit traffic within a greater Eurasian transit zone are absolute necessities. Moreover, Elbegdorj and many other Mongolian policymakers are clever enough to recognize that the Chinese-Russian political rapprochement, which is based on economic self-interest, can only profit Mongolia if Mongolia is seated at the negotiating table and participating in drafting new transport and energy growth models. Thus the U.S. and other democracies should be supportive of Mongolia’s strategy of trust building as possibly leading to greater Northeast Asian political stability and being economically beneficial to American allies such as Japan, South Korea, and Australia.

|

Progress after Dushanbe

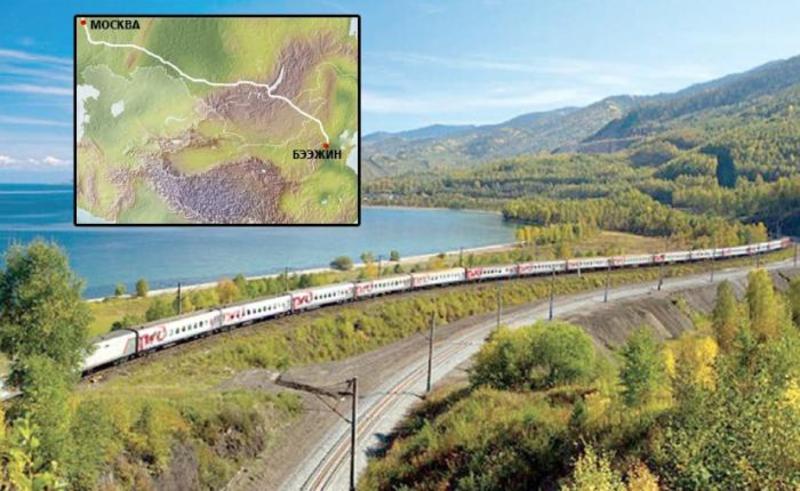

Since the tripartite summit, the Mongols have moved to maintain the momentum of Sino-Russo-Mongolian cooperation. Elbegdorj announced after the SCO that Ulaanbaatar would host a meeting on implementing the Railway Transit Transportation agreements just signed among the three governments and set up a working group to study linking Central Asia’s natural gas fields to China and South Korea through Mongolia via Russia’s “Western Corridor of Natural Gas.”9 The Mongolian government on October 15th at the 18th regular meeting of the Mongolian-Russian Intergovernmental commission on trade, economic, science and technical cooperation initiated a Steppe Road highway project together with the Russian company Dalistroimachanizasiya to develop a 997 km highway, 1100 km high voltage electrical line, gas and oil pipeline from Altanbulag at the northern border through Ulaanbaatar to Zamin Uud on the southern border.10 On October 20th an MOU for a high speed rail line project linking Beijing and Moscow through Mongolia was signed by Russia and China during a visit to Moscow by the Premier of the PRC State Council Li Keqiang. This new passenger train project would reduce the 7000 km journey from 6 days to 2. Cost projections for the new rail line are set at US$ 230 billion on a 5-year construction time schedule.11 The line would parallel the route of the present Ulaanbaatar Railway, which likely would be turned over solely to freight traffic. A few days later in Mongolia’s parliament a draft bill was approved that permits for the first time narrow-gauge (1,435 mm) railroad spurs from coal processing plants to the Chinese border for transporting raw minerals (Tavantolgoi-Gashuunsukhait, Sainshand-Zamiin Uud, and Khuut-Bichigt), contingent on agreement on border crossing cooperation between Mongolia and China. The Russian wide gauge (1,520 mm) spurs were approved for Arts Suuri-Erdenet, Tavantolgoi-Sainshand-Baruun-Urt-Khuut-Choibalsan, and Khuut-Numrug, while the Sainshand and Zamiin Uud lines were eliminated from the government’s proposed plan because of the new Sino-Russo rail agreement.12

The above-mentioned transport and energy projects clearly indicate that Mongolia is now well positioned in the middle of Chinese and Russian plans to expand their transportation cooperation throughout the Eurasian region. This trend is likely to continue, particularly with the continuing delay on the development of the second phase of the giant Rio Tinto-controlled copper and gold deposit at Oyu Tolgoi. That project has been touted as inextricably linked to Mongolia’s economic development. While that assessment is still true, Mongolia has many domestic factors to consider before coming to a final solution on how to proceed. With the indecision and delay, western investors have grown weary and leery of entering into big new mining projects in Mongolia at the central government level which might be derailed by local and environmental groups locked out of the original negotiating processes. Also, many Mongols are uncomfortable with the present reality of major western companies acting as middlemen to move Mongolian raw minerals to Chinese customers—a pattern that further strengthens Chinese monopoly over its economy.

|

Mongolia now has an alternative to this type of foreign investment—increase its role as a transit corridor in the region as it simultaneously develops its dual rail gauge infrastructure in a more balanced manner so that its products are better able to reach new trade partners, and it profits in transit fees from exploding Sino-Russian trade.

Ultimately this plan could break China’s stranglehold on Mongolian trade by helping Japan, South Korea, Southeast Asia and Vietnam sell their goods as alternatives to Chinese ones to Mongolia, especially if North Korean ports are developed to avoid Vladivostok congestion. Also, a modernized rail system across Eurasia would permit Turkey, the Middle East, Iran, and Europe to grow their trade with Mongolia in a substantive fashion. However, the ever present danger of this new game plan lies in Mongolia’s ability to manage the influence of the Sino-Russian partnership in its domestic political scene. Mongolian history tells us that rising Chinese and Russian economic ties brought strong political pressures and even bloody competition. As the 21st century progresses, the challenge of balancing economic benefit and national security remains key for Mongolian leaders.

|

Alicia Campi has a Ph.D. in Mongolian Studies from Indiana University, was involved in the preliminary negotiations to establish U.S.-Mongolia bilateral relations in the 1980s, and served as a diplomat in Ulaanbaatar. She has a Mongolian consultancy company (U.S.-Mongolia Advisory Group), and writes and speaks extensively on Mongolian issues. She has published over 80 articles and book chapters on contemporary Mongolian, Chinese, and Northeast Asian issues, and advises Chinese and western financial institutions on Mongolian investment, particularly in the mining sector. She is the author of The Impact of China and Russia on U.S.-Mongolian Political Relations in the 20th Century.

Recommended citation: Alicia Campi, “Transforming Mongolia-Russia-China Relations: The Dushanbe Trilateral Summit”, The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 12, Issue 45, No. 1, November 10, 2014.

Related articles

• Peter Lee, Mongolian coal’s long road to market: China, Russia and Mongolia

• Peter Lee, A New ARMZ Race: The Road to Russian Uranium Monopoly Leads Through Mongolia

• MK Bhadrakumar, Sino-Russian Alliance Comes of Age: Geopolitics and Energy Politics

• Geoffrey Gunn, Southeast Asia’s Looming Nuclear Power Industry

• MK Bhadrakumar, Russia, Iran and Eurasian Energy Politics

Notes

1 Economic growth in Mongolia decelerated sharply from 8.7% year on year in the final quarter of 2013 to 7.5% in the first quarter of 2014 and to 3.8% in the second, as stimulus was partly withdrawn and foreign direct investment plunged by 62.4%, tamping down investment by 32.4%. ADB, Asian Development Outlook 2014 Update (Manila, 2014).

2 Author’s interviews, Ulaanbaatar, August 7-8, 2014.

3 From the Natsagdorj poem, “My Native Land.” Xi read this to open his August 21, 2014 speech to the Mongolian parliament.

4 “Answers to journalists’ questions following a working visit to Mongolia,” President of Russia website (September 3, 2014).

5 With the exception of a tripartite meeting held almost a century ago at the level of vice foreign ministers. G. Purevsambuu, “First-ever summit held between Presidents of Mongolia, Russia, and China,” The Mongol Messenger (September 19, 2014).

6 “China, Russia, Mongolia to Create Economic Corridor,” thebrickspost (September 12, 201).

7 Mongol Messenger (September 19, 2014); website of President of Mongolia (September 11, 2014).

8 Mongol Messenger (September 19, 2014).

9 Elbegdorj speech, website of President of Mongolia (September 11, 2014).

10 “B. Ooluun, “1000 km highway planned to connect China and Russia,” The Mongol Messenger (October 17, 2014).

11 “Russia and China high speed rail line across Mongolia project MoU signed,” Montsame

(October 20, 2014).

12 “State Policy on Railway Transportation finally approved,” Montsame (October 24, 2014).