Introduction

The Japan-Korea solidarity movement to support the democratization of South Korea was active throughout the 1970s and 1980s in Japan among Korean residents (Zainichi1) and Japanese intellectuals and activists. Korean activists in the democratization movement have recalled the widespread international support of that era (Chi 2003, 2005; Park 2010; Kim 2010; Oh 2012), and Zainichi and Japanese activists have written about their activities in numerous books and memoirs (Chung 2006; Tomiyama 2009; Shouji 2009; Chung 2012). However, the Japan-Korea solidarity movement has been relatively neglected in both Korean and Japanese scholarship. The few academic articles that mention the movement mainly focus on the activities of Zainichi (Cho 2006) and Christians (Lee 2012). This article extends analysis of the solidarity movement to show how its activities led to a process of self-reflection and self-transformation within Japan.

In order to understand the movement, we need to examine its historical context. Although the mass anti-US-Japan Treaty movement of 1960 (Anpo Tōsō) pivoting on tightly organized ideological sects ultimately failed, it paved the way for a new type of civic activism based on independent, self-organizing, and voluntarily participating individuals.2 This new type activism came to the fore in the subsequent anti-Vietnam War movement, which began to reconsider the relationship between Japan and Asia (particularly Vietnam). While denouncing US imperialism and aggression in Vietnam, many public intellectuals and activists came to question Japan’s own past imperialism in Asia and its contemporary role in supporting the war under the US-Japan military alliance. This questioning led to “a shift from a comfortable mythology of national victimhood to a new morality founded on individual responsibility for both the past and the present” (Avenell 2010, 122). In other words, the sense of responsibility for Asia that emerged during the anti-Vietnam War movement extended to Japan’s previous misdeeds as a colonial power.

The first part of this paper examines the international political and economic conditions surrounding South Korea and Japan in the postwar era and societal reactions to these conditions. It then traces the development of the movement through four stages: 1) from a support movement toward a process of self-questioning; 2) from self-questioning to recognition of the need for self-reformation through solidarity; 3) expansion of networks within the solidarity movement, and 4) evolution of the solidarity movement toward reflexive democracy. These phases were identified through analysis of publications and documents published by, and interviews with, key participants. By illuminating the evolution of the Japan-Korea solidarity movement and its role in Japanese society’s turn toward reflexive democracy, I hope to contribute to the understanding of Japanese social movement history, particularly transnational activism studies in Asia.

Background of the Japan-Korea Solidarity Movement

1) International political-economic structure and the Japan-Korea Treaty of 1965

U.S. occupation, the Cold War and the division of Korea defined the economic and political situation of post-colonial South Korea. Following liberation from Japanese rule in 1945, South Korea experienced U.S. military rule and was heavily dependent on the United States for aid and political direction. As part of the U.S.-led anti-communist bloc in northeast Asia, the governments of South Korea and Japan opened talks in 1951 for establishment of diplomatic relations amidst the Korean War. Given the huge gap in perceptions of the two governments concerning the colonial era, the talks stalled. However, after Park Chung Hee seized power in South Korea in a military coup in May 1961, the talks eventuated in the Treaty on Basic Relations between Japan and the Republic of Korea in 1965. The treaty adopted the language of “economic cooperation” instead of “apology” and “reparations” for the colonial past, as shown by its name: “Agreement between Japan and the Republic of Korea concerning the Settlement of Problems in regard to Property and Claims and Economic Cooperation.” The Japan-Korea Treaty established political-economic ties between the two U.S. allies under the Cold War system, rather than normalizing relations between the former colonizer and the former colonized. In the wake of the Japan-Korea Treaty, the politics and economy of South Korea became more dependent on Japan as well as the United States. In the context of this hierarchically linked three-party political-economic structure, Korean activists struggled, not only for human rights and democracy domestically, but also against U.S. and Japanese support for the military regime in South Korea.

Korean intellectuals and students, in particular, criticized the Japan-Korea Treaty for failing to obtain Japan’s apology and reparations for its colonial past. Korean thinkers and activists denounced the subordinate economic relationship between South Korea and Japan as “neocolonialism,” arguing that the Japan-Korea Treaty and Japanese economic advances in South Korea marked the “re-establishment of a high degree of influence and control by the colonial power whose depredations are so vividly remembered – Japan” (McCormack and Selden 1978, 9). Thus, in order to democratize Korean society and improve human rights and labor rights, Korean activists protested not only against their own government, but also against the Japanese government and Japanese corporations. However, in part because of the military regime’s control of the media, the harsh critiques leveled by Korean activists against Japan’s colonial past were little noted in Japanese society.

2) Information networks amplify the voices of struggling Koreans

Most Japanese activists in the 1960s were scarcely aware of the nationwide movement of 1964-65 opposing the Japan-Korea Treaty movement in South Korea (Takasaki 1996). However, the anti-Vietnam War movement in Japan provided a pool of Japanese activists, many of whom would become interested in the anti-government movement in South Korea. The anti-Vietnam War movement increased interest in Third World liberation movements in Asia. Specifically, it raised questions about the relationship between Japan and Asia, and the nature of the Zainichi, who comprised 88 percent of foreign residents in Japan in 1965.3 In the late 1960s and the early 1970s, Zainichi had launched an anti-ethnic-discrimination movement with the cooperation of principled Japanese intellectuals and students. As Japanese became more interested in the voices of Zainichi, the Zainichi movement for the democratization of South Korea also caught the attention of some Japanese activists.4 Increasing awareness of Asia and the Zainichi led to growing interest among some Japanese in learning about the Korean democratization movement.

At the same time, Korean activists sought to raise international awareness of and support for their movement. In late 1972, when the Yushin Constitution5 strengthened Park’s grip on the presidency and blocked domestic opposition, Korean opposition leaders like Kim Dae Jung tried to pressure the military regime by criticizing it from outside, and by building solidarity among overseas Korean compatriots. In addition, in 1973 in Tokyo, Oh Jae Shik, the secretary of the Urban Industrial Mission of the Council of Churches in Asia, established a Documentation Center for Action Groups in Asia to collect and translate information about and for South Korean activists (Lee 2012; Oh 2013). The effort to collect and share the voices of Koreans internationally became more systematic with the cooperation of Japan’s leading progressive opinion magazine, Sekai, and with the close relationship between Japanese and Korean churches.

The monthly magazine Sekai played an important role in introducing the voices and thoughts of Koreans. Sekai published “The Korean Student Movement in the 1970s” by Nakagawa Nobuo, a Zainichi intellectual. Nakagawa introduced the argument of Korean students who held that Japan was an obstacle to the democratization and reunification of Korea, and that students should therefore advance the anti-Japan movement (Nakagawa 1972). In an interview with the editor in chief of Sekai, Yasue Ryōsuke, Kim Dae Jung criticized the Japan Socialist Party and the Japan Communist Party as well as progressive social groups for aligning themselves with North Korea while neglecting movements for social change in South Korea. He called on conscientious Japanese to “correctly recognize” South Korean democracy movements (Kim 1973: 118). Moreover, “Letters from South Korea,” written by T.K Sei, a pseudonym of Chi Myung Kwan, was serialized in Sekai soon after the Kim Dae Jung kidnapping incident in August 1973. This series (1973~1988), made possible by messengers who secretly carried underground information from South Korea to Japan, provided detailed information on the Korean struggles in the face of the Park regime’s repression (Chi 2003, 2005; Lee 2012).

International Christian networks operating between Japan and South Korea played an important role in sharing information. Many Korean Christians had studied at Japanese theological seminaries during the 1950s and the 1960s and had met Japanese Christians in other countries where they had gone for study or for international conferences and workshops. These networks linking Japanese and Korean Christians, especially progressive Christians, were strengthened in the context of the world ecumenical movement. In the early 1970s, the National Council of Churches in Korea (NCCK) and the National Council of Churches in Japan (NCCJ) institutionalized annual meetings; the first was held in Seoul on July 2-5, 1973. The participants discussed (1) Japan’s economic advance, (2) the legal status of Zainichi, (3) Koreans in Sakhalin, (4) Japan’s immigration law, (5) Korean victims of the atomic bombing, (6) the Yasukuni Shrine, (7) sex tourism, and (8) history textbooks. The meeting produced a resolution calling for further cooperation (NCCK 1987). In short, Christian networks started to discuss and share their mutual criticisms of the Japanese government and mainstream Japanese society, Japan-Korea relations and the Park dictatorship.

These religious, social, and media pathways linking activists created a discursive political space for a transnational “imagined community” (Anderson 1983). Koreans and Japanese intellectuals and activists, who indirectly and directly communicated with each other, started to construct a common understanding and interpretation of Japan-South Korea relations. This was the background of the Japan-Korea Solidarity movement in Japan.

Development of the Japan-Korea Solidarity Movement

1) “Saving” in the early 1970s: from “helping” to “self-questioning”

In the early 1970s, when information infrastructure was not yet systematized, several groups formed a support movement for Korean prisoners of conscience. These prisoners included Kim Chi Ha, a poet with a strong anti-authoritarian stance, and the Suh brothers (Suh Sung and Suh Joon-sik), Zainichi who had come to South Korea for education and were arrested and sentenced as spies. The groups were formed in the context of growing interest in revolution and activism in Asia and Zainichi issues.

Poet Kim Chi Ha was one of the earliest Korean democratic figures to gain prominence in Japan. The movement to support Kim Chi Ha was formed upon his arrest under the anti-Communist Act6 for his poem “Groundless Rumors” (Piŏ), published in the Catholic magazine Changjo in April 1972. Two advocacy groups formed in Japan: one was founded by artist-activist Tomiyama Taeko, and the other by Oda Makoto, novelist and spokesperson of the Citizen’s League for Peace in Vietnam (Beheiren 1965-1974). The former group7 (organized on April 19, 1972) mainly sought to convey Kim Chi Ha’s ideas through paintings and plays8 (figure 1 and 2).

|

Figure 1. Postcard of AI Japan. Tomiyama’s painting is based on Kim Chi Ha’s poem “Bronze Yi Sun-sin” |

The latter group (organized on May 9, 1972 and headed by Oda) organized a “group to visit South Korea” to hand the Korean government a petition demanding the release of Kim Chi Ha (Tsurumi and Kim 1975). With little information on Kim or the Korean democratization movement, meeting him at the prison hospital came as a shock for the group. According to writer Tsurumi Shunsuke, when he presented Kim with the petition “for which we collected signatures from all over the world to demand that you not be given the death sentence,” Kim replied, “Your movement cannot help me, but I will add my voice to help your movement” (Tsurumi et al. 2004, 337). Tsurumi recalled his surprise at Kim’s strong statement, having expected gratitude. However, this response made him reflect on his naivety concerning a distant sufferer like Kim Chi Ha. As an activist opposing the Japan-Korea Treaty during 1964 and 1965, Kim had problematized the emerging collaboration between the Korean military regime and the former Japanese colonial power. Kim’s reaction to Tsurumi and the support movement enabled Japanese activists to that they should support the struggles of Korean activists through their own movement to question Japan’s role in Korea (Wada 1975a).

The arrest of the Suh brothers (Suh Sung and Suh Joon-sik) presented another important issue in the early 1970s. The Army Security Command of South Korea arrested fifty-one people in the “Zainichi students spy incident” on April 20, 1971, just one week before the presidential election in South Korea. Suh Sung was singled out as the leader of the alleged spy group. During interrogation, he underwent torture severe enough to make him attempt suicide, and he was sentenced to death.9 In respondse to the arrest and the court proceedings, the Suh brothers’ family, classmates, and friends, as well as Zainichi organizations and various Japanese activists organized a movement supporting the Suh brothers.

The Committee to Save the Suh Brothers (organized on October 23, 1971) was an umbrella organization intended to unify activities in Tokyo and Kyoto. Shoji Tsutomu, a Protestant pastor and representative of the committee, was almost entirely ignorant of the historical relationship between Japan and South Korea and of the conflict resulting from the division of Korea at that time (Shoji 2009, 28). Initially, the call to save the Suh Brothers was based on a humanitarian approach and their “Japanese-ness.” The death sentence appeal, published in the Committee’s first bulletin (October 1971), ended by noting: “these Zainichi Korean brothers were born in Japan and spent their youth in Japan. When they face death in the severe political situation, how can we Japanese remain silent?”10 By emphasizing the “Japanese-ness” of the Suh Brothers, the committee tried to attract sympathetic attention from Japanese citizens.

|

Figure 2. Leaflet from theatrical performance based on “Bronze Yi Sun-sin” |

However, the humanitarian initiative calling for support of the Zainichi brothers, who were born and raised in Japan, soon developed into more reflexive questioning of Japan’s role in their suffering. Shoji reflected that Suh Sung’s final statement in court11 provided the movement with a turning point; they started to question Japanese policies that supported the military regime of South Korea and prevented the unification of Korea (Shoji 2009, 62-63). Thus, commitment to the support movement led activists to greater awareness of the Zainichi perspective, and to question Japan’s relationship with South Korea.

The movement began with a small number of Japanese intellectuals and activists as a support movement based on helping the distant other, the Japanese-like Zainichi. However, it soon evolved into a questioning of Japan’s role in shaping Japan-Korea relations and the division of Korea. This critical attitude emerged with direct contact and communication with Kim Chi Ha, Suh Sung and others, as well as a growing atmosphere of civic activism that questioned Japan’s role during the global anti-Vietnam War movement.

2) “Self-reformation” through solidarity in the mid-1970s

On August 8, 1973, Kim Dae Jung, South Korea’s opposition leader, was kidnapped in Tokyo by the Korean Central Intelligence Agency (KCIA). This incident made even ordinary Japanese aware of opposition to the military regime in South Korea. Right after the kidnapping incident, Zainichi dissident groups became active to support Kim Dae Jung and made efforts to raise awareness among Zainichi and Japanese citizens about the Korean democratization movement.

The first Japanese group to respond to the kidnapping incident was from the anti-Vietnam War movement (Aochi and Wada eds. 1977, 62-63). Triggered by the kidnapping and the ensuing protests and demonstrations in South Korea,12 anti-Vietnam War and other activists in Japan held a series of meetings to organize an umbrella group to bring together the disparate support groups that had emerged earlier. They called the new group the Council for correcting Japanese policy on South Korea and for solidarity with the democratization movement of South Korea (日本の対韓政策をただし、韓国民主化闘争に連帯する日本連絡会議), for short, the Japan-Korea Solidarity Council (organized on April 18, 1974).

As their formal name suggests, solidarity implied changing Japanese foreign policy, which, by supporting the military regime in South Korea, obstructed democratization and unification. In the November 1975 issue of Sekai, Wada Haruki, general director of the Japan-Korea Solidarity Council, wrote:

The democratization movement of South Korea is teaching us the meaning of pursuing democracy and human rights. Moreover, it teaches us what Japan has done in South Korea. From our current situation, we still need to learn more. This is the meaning of solidarity (Wada 1975a 53-54).

Solidarity was understood as a process of listening to and learning from the voices of the struggling others toward the goal of self-reformation. This attitude was also found among Japanese Christians.

Japanese Christians organized a solidarity group called the Emergency Christian Conference on Korean Problems (ECC, on January 15, 1974). Responding to harsh critiques from Korean Christians and activists, progressive Japanese Christians formed the ECC to address Japan’s colonial past as well as ongoing neo-colonialism, both of which structured the relationship between Japan and Korea. In its founding statement, the ECC explained how it was inspired by Korean activists to begin a process of self-reformation:

We were shocked to receive such harsh critiques and demands, born from their fearless faith-based struggles. That is, the Korean political situation in which people are risking their lives is related to Japan’s past colonization and current economic invasion. This problem is what we Japanese have to be responsible for before God.13

At its founding meeting, the ECC decided to investigate Japanese corporate encroachment in South Korea, as well as sex tourism and other issues between Japan and South Korea. In other words, through solidarity activities, the ECC tried to learn not only about the situation of others, i.e. Koreans, but also the cause of their suffering structured by the Japan-South Korea relationship. This learning process was the basis for a new imagined community linking activists beyond borders.

|

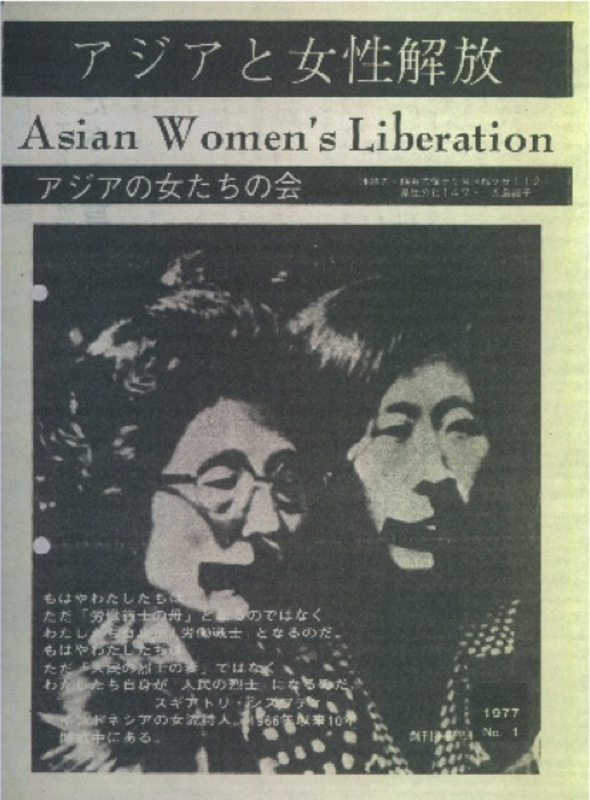

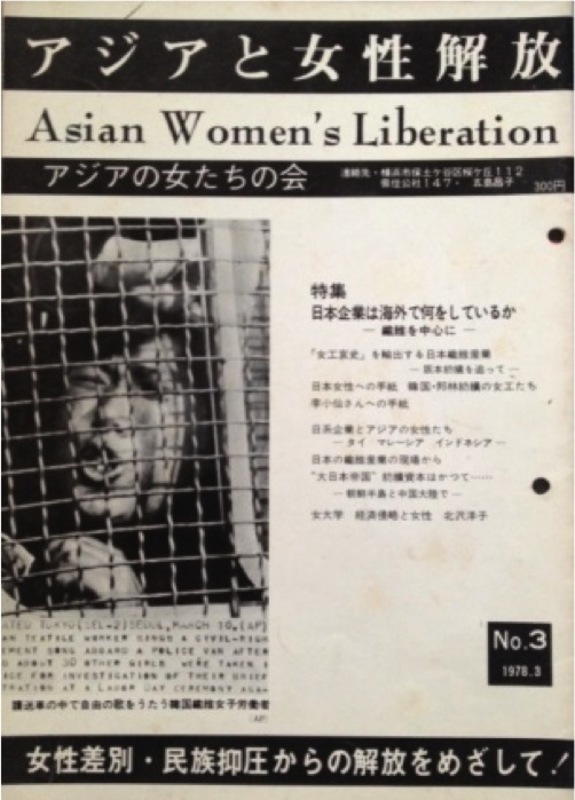

Figure 3a. Cover Photo of Asian Women’s Liberation. From the first to third issues, covers depicted Korean women’s struggle for democracy and labor rights. |

3) Enlarging networks among Zainichi, women, and laborers in the mid-1970s to the early 1980s

Cooperation among Zainichi and Japanese activists, including Christians, was remarkable, especially on the issue of Zainichi prisoners of conscience who were held in South Korea on charges of espionage. Zainichi family members organized the family association in May 1975 and fifty-four groups of Japanese activists formed the National Council to support Zainichi Political Prisoners in June 1976. These groups worked together to raise public support, both domestically and internationally, and to promote activities such as visiting and sending letters and cards to–prisoners of conscience in South Korea. In addition, representatives working for Zainichi prisoners of conscience visited the United Nations and Amnesty International in London to appeal for global support for the Zainichi prisoners.14

The growing networks among solidarity groups extended to the women’s movement. The women’s solidarity movement was born out of the issue of sex tourism, called Kiseng15 Kankou. The Japanese and the Korean National Council of Churches met together officially for the first time in July 1973; responding to a special request by the Council of Korean Christian women, the problem of sex tourism was placed on the agenda. Korean Christian women inspired Japanese Christian and non-Christian women to organize the group Women against Kiseng Kankou. At that time, anti-sex tourism movements sprung up not only in Korea but in Taiwan as well. Matsui Yayori, a well-known Asahi Shimbun foreign correspondent, played an active role in the anti-sex-tourism movement in Japan and in forging bonds with women activists throughout Asia.

On March 1, 1977, Matsui, Tomiyama Taeko, and several other women activists, most of whom had participated in the anti-sex tourism movement, organized the Asian Women’s Association. The founding statement declared their opposition to economic invasion and sex-exploitation. Reacting to the voices of Korean and other Asian women and “learning” from them, these Japanese women activists also formed a solidarity movement dealing with such issues as human rights, labor rights, and the colonial past, all of which were pertinent to East and Southeast Asian women.

Korean women’s struggles were the primary focus of the Asian Women’s Association. The cover photo of Asian Women’s Liberation, the bulletin of the Association, showed Korean women fighting against the repressive military regime (figure 3). In later years, the members of the Asian Women’s Association focused more specifically on war crimes committed against women, particularly the wartime “comfort women.”16

|

Figure 3b. Cover Photo of Asian Women’s Liberation. From the first to third issues, covers depicted Korean women’s struggle for democracy and labor rights. |

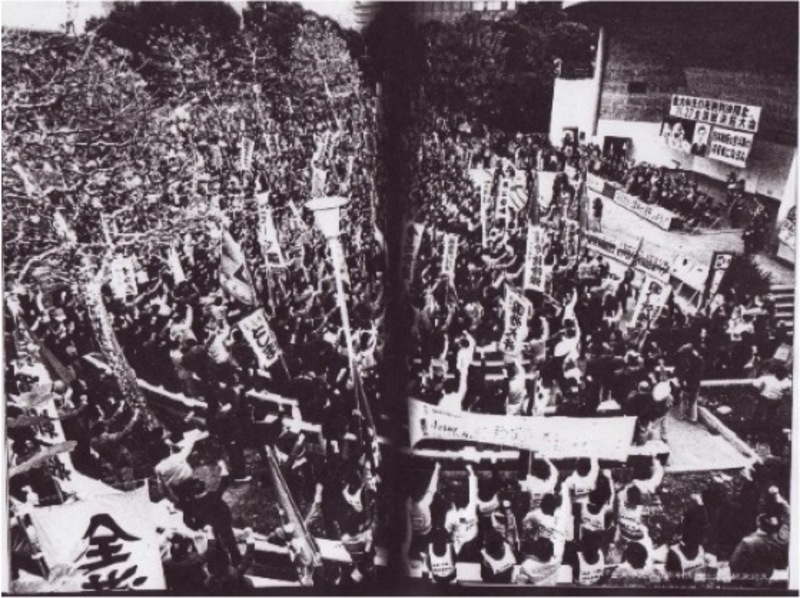

The solidarity movement further broadened to include organizations devoted to the labor movement, which had long shown great sympathy toward North Korea. In the late 1970s, responding to the increasingly wide-ranging solidarity movement among Japanese activists, Christians, and Zainichi, Japanese labor-movement activists also joined in solidarity activities.17 The involvement of the General Council of Trade Unions of Japan (Sōhyō) in the Japan-Korea solidarity movement was triggered by the Kwangju Uprising and the Kim Dae Jung crisis in 1980.18 Responding to the arrest of Kim, Zainichi dissident groups, civic solidarity groups, Christian groups, and even Sōhyō joined the solidarity movement. In order to coordinate their activities, a Meeting of Representatives to Free Kim Dae Jung was held on July 11, 1980 by Sōhyō and other groups; progressive political parties and the Council for Japan-Korea solidarity also joined. At this meeting, the participants organized the Japan Council for Saving Kim Dae Jung and set a goal of collecting ten million signatures.19 According to Watanabe Tetsuro, the secretary for political affairs of the Tokyo office of Sōhyō, the campaign to collect ten million signatures on behalf of a foreign national was “the first and might be the last time”20 such an effort was undertaken in Japan. With Sōhyō’s participation, the number of people who attended the rallies and signed petitions dramatically increased21 compared to previous solidarity activities based on mainly civic participation (Figure 4).

The Japan-Korea solidarity movement peaked when Kim Dae Jung was sentenced to death on September 17, 1980. The movement quieted down when his sentence was eventually commuted to life imprisonment, and he and his family left for the United States at the end of 1982. Although the mass movement subsequently declined, it continued to work on specific issues, such as Zainichi prisoners of conscience, while responding to new issues that arose in the 1980s.

4) Reflexive democracy in the 1980s

By the early 1980s, Japan’s initial support movement based on humanitarian ideals developed into a more reflective phase of self-reformation (自己変革) through listening to and learning from the voices of others. Self-reformation involved questioning Japan’s role in Korea and rectifying Japanese foreign policy concerning Korea. After the intensity of the Kwangju Uprising and the life-threatening crisis for Kim Dae Jung, solidarity movement activists broadened their agenda to include such issues as history textbook treatments of Japanese colonialism and war and the movement protesting the fingerprinting system that singled out Zainichi, while continuing to call for solidarity with the South Korean democratization movement.

In 1982, China and South Korea challenged the revision of Japanese history textbooks, which softened the description of Japanese aggression in Asia as mere “advance.”22 The Emergency Christian Conference on Korean Problems (ECC) and the Council for Japan-Korea Solidarity demanded that the Japanese government “correct the wrong descriptions of Korea, … learn from the critiques by Koreans,” and “apologize for past colonial rule and strive to relax tensions on the Korean peninsula” (Leaflet, August 6, 1982). In addition, the Tokyo local of Sōhyō raised the history textbook issue in a document titled “Call for Japan-Korea Solidarity Actions” (October 16, 1982) and sent to their affiliated labor unions. Solidarity movement activists started to speak out about unsettled issues of the colonial past, demanding that the Japanese government accept responsibility for thirty-six years of colonial rule in Korea.23

|

Figure 3c. Cover Photo of Asian Women’s Liberation. From the first to third issues, covers depicted Korean women’s struggle for democracy and labor rights. |

On September 4, 1984, a collective meeting to protest the visit to Japan by South Korean president Chun Doo Hwan brought together the Japan Socialist Party and Sōhyō24 with groups associated with Wada Haruki (general director of the Japan-Korea Solidarity Council), Tomiyama Taeko, and Yoshimatsu Shigeru (general director of the National Council to Support Zainichi Political Prisoners). The meeting issued the following resolution:

The genuine resolution of the colonial past should begin with an apology to all Korean Minjung expressing the will of the people, including a resolution in the Diet. … With today’s meeting opposing the visit of Chun Doo Hwan, we strive to establish true friendship between Japan and Korea and will work to achieve the civil rights of Zainichi, including abolition of the fingerprinting system, and promote the peaceful unification of Korea.

As shown, the Japan-Korea solidarity movement turned to issues that directly addressed Japan’s internal concerns. Thus, while committing to the solidarity movement with Zainichi activists and sharing the cause of struggling Koreans, Japanese conscientious intellectuals and activists reflected on Japan’s unsettled colonial past and on discrimination against Zainichi.

During the 1980s, the cooperation between Zainichi and Japanese intellectuals and activists broadened to include the “anti-fingerprinting system”, which resulted in the abolition of the system in 1992. Subsequently, efforts related to unresolved colonial problems came to the fore in both South Korea and Japan after the democratization of South Korea. The Kono Statement (1993) on the recognition of and apology for comfort women and the Murayama Statement (1995), which apologized to Asian victims of Japanese imperial rule for the first time at the level of the Diet, may be seen as accomplishments due in part to the Japan-Korea solidarity movement.

While the Japanese sense of responsibility and attitude of self-questioning began to emerge as early as the 1960s with the anti-Vietnam War movement, concrete proposals and actions toward “self-reformation” did not become central to civic activism until the Japan-Korea solidarity movements of the 1970s and 1980s. The Japan-Korea solidarity movement provided an opportunity to listen to and learn from others’ viewpoints. With direct voices of the others, Japanese society became more sensitive to issues of war crimes and the human rights of Zainichi and other minorities. Thus, solidarity with “others” (Korean activists and Zainichi) simultaneously spurred a movement for reflexive democracy.

Conclusion

|

Figure 4. Japanese protesters rally under the banner, “Don’t Kill Kim Dae Jung!” on Nov 27, 1980 (photographed by Hashiguchi Jōji, February 1981, Sekai). According to Wada (1982), 7,000 people attended this rally. |

The anti-Vietnam War movement touched off public questioning in postwar Japanese society on the nature and history of its relationship with Asia. This self-questioning of Japan’s role evolved into self-reformation with concrete agendas and actions during the Japan-Korea solidarity movement, ranging from rectifying Japanese support for the South Korean military dictatorship to calls to settle the colonial past and cooperate with Zainichi’s anti-ethnic discrimination movement. Ultimately, Japanese citizens pushed for internal change toward a more reflexive democratic system. This evolution toward reflexive democracy through the Japan-Korea solidarity movement should be understood not only in the context of the worldwide anti-Vietnam War movement, but also as a product of the growth of formal and informal networks among Koreans, Zainichi, and Japanese.

Through the Japan-Korea solidarity movement in the 1970s and 80s, progressive Japanese and Korean activists and intellectuals constructed an imagined community by sharing issues and concerns about democracy, peace and social justice in Asia. However, many critics have noted that these networks, which transcend national borders, peoples, and sectors, have faced increasing challenge in public discourse since the mid-1990s. Over the last twenty years, Japanese society has witnessed a counteroffensive to erase and deny Japan’s war crimes, including the sexual exploitation of women. Recently, hate speech vilifying Zainichi has found a new younger audience and mobilizing force through the Internet.

World geopolitics and political economy have changed dramatically since the end of the Cold War with the collapse of the Soviet Union and the demise of the Communist bloc. The counteroffensive, including hate speech against Zainichi, could be interpreted in part as a Japanese reaction to neoliberal globalization intensified by the collapse of the Japanese bubble in 1990 and subsequent economic crisis. However, just as principled Korean, Zainichi, and Japanese activists countered the Cold War political economic system that structured the relationship between Japan and South Korea in the 1970s and 80s, the question remains whether new forms of transnational solidarity will emerge to give voice to those who have been silenced and to promote peace in Asia today.

Misook Lee is Project Assistant Professor, Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, University of Tokyo.

Recommended citation: Misook Lee, “The Japan-Korea Solidarity Movement in the 1970s and 1980s: From Solidarity to Reflexive Democracy,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 12, Issue 38, No. 1, September 22, 2014.

Notes

1 Zainichi are Korean residents of Japan who trace their roots to Korea at the time of Japanese colonial rule and who remain Korean citizens, including those born in Japan. The Zainichi community was politically divided between Sōren, established in 1945 and affiliated with North Korea, and Mindan, established in 1946 and affiliated with South Korea. However, many Zainichi did not align with either Sōren or Mindan, and some who were originally affiliated with Mindan separated from that group and espoused solidarity with the democratization movement of South Korea.

2 The Anpo Tōsō was “a moment remembered by academics and activists alike as the birth of independent citizen protest in postwar Japan” (Avenell 2010, 13).

3 Data from Statistics Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communication.

4 The movement was led by several groups: the Korean Student Coalition, the Korean Youth Coalition, and the Mindan Tokyo office, which were critical of Mindan. Basically Mindan is affiliated with South Korea. However, when Park Chung Hee came to power with a military coup in South Korea, several groups within Mindan opposed its decision to support the military regime and separated from Mindan. See Miyata (1977) and Cho (2006).

5 President Park Chung Hee consolidated and systematized his power through the Yushin Constitution, which stipulated that the president would be elected for a six-year period with no limitation on the number of terms. See Dewind and Woodhouse (1979).

6 The act was passed in 1961, just after Park Chung Hee’s military coup. It “provides that persons who belong to, are affiliated with, praise or in any other way encourage or benefit a communist organization may be punished by imprisonment at hard labor for five to seven years” (Dewind and Woodhouse 1979, 15). The act was abolished in 1980, when it was integrated into the National Security Law.

7 In 1973, this group was dissolved and was absorbed by Amnesty International in Japan’s newly formed group “Kakyō” (架橋).

8 Theatrical performance based on Kim Chi Ha’s “Bronze Yi Sun-sin.” The original Korean title is Kuri Yi Sun-shin. Yi Sun-shin was a naval commander in the Chosŏn dynasty, famed for his victories against the Japanese navy during the Imjin War; he became a national hero. In this play, Kim Chi Ha criticized the Korean power elites who enjoyed wealth and power from collaboration with imperial Japan and exploited the poor and powerless people.

9 For more details, see Suh (1994). Suh Sung spent 19 years in the prison.

10 The Committee to Save the Suh Brothers (1992, 11).

11 See, Suh (1994). In his final statement, Suh Sung articulated that he would keep struggling for the Unification of Korea and pursuing positive nationalism. See, also, The Committee to Save the Suh Brothers (1992, 166).

12 The Seoul National University students’ uprising on October 2, 1973, the one-million-person petition movement in December 1973, and a series of student uprisings in early 1974 had occurred in South Korea.

13 ECC statement, January 15, 1974. See, ECC (1976).

14 See Kim (1986). Representatives working for Zainichi prisoners of conscience visited international organizations eleven times from the beginning until 1985.

15 The term Kiseng was originally made and used in pre-modern Korea, meaning a female entertainer and courtesan. The same term was also used to describe the sex tourism of Japanese businessmen in the 1960s and 1970s.

16 Matsui Yayori established the Asia-Japan Women’s Resource Center in 1994, organized the Violence against Women in War Network (VAWW-NET) in 1998, and proposed the Women’s International War Crimes Tribunal on Japan’s Military Sexual Slavery, which was held in Tokyo in 2000 with international cooperation. For more about Matsui Yayori, see the Women’s Active Museum on War and Peace.

17 Interview with Watanabe Tetsuro (November 9, 2011).

18 On May 18, 1980, in Kwangju, a city in southwestern South Korea, pro-democracy students and citizens demonstrated against martial law in Kim Dae Jung’s political base. The military regime sent in the army to crush the uprising. The result was a massacre. The government accused Kim Dae Jung of leading the Kwangju Uprising in an attempt to overthrow the government.

19 The number of signatures they had been able to collect by April 1981 was 5,258,819 (Wada 1982).

20 Interview with Watanabe (November 9, 2011).

21 The number of people who attended the national rally was approximately 15,000 on August 8, 17,000 on September 17, 6,000 on November 13, 7,000 on November 27, 7,000 on December 5, and 15,000 on December 22 (Wada 1982).

22 On the dispute concerning Japanese textbooks, see Nozaki and Selden (2009),

23 See Wada Haruki, Ishizaki Koichi, and the Sengo Gojunen Kokkai Ketsugi o Motomerukai, eds. (1996).

24 The Japanese government chose to compensate the victims through a private Asian Women’s Fund collected by voluntary Japanese citizens. Because the Japanese government did not accept national responsibility for compensation, many South Korean victims refused to accept monetary compensation from the Asian Women’s Fund. See Kim (2006), Morris-Suzuki (2007).

References

Aochi, Shin and Wada Haruki, eds. 1977. Nikkanrentai no Shisō to Kōdō [Thought and Actions of Japan-Korea Solidarity]. Tokyo: Gendaihyōron-sha.

Avenell, Simon A. 2010. Making Japanese Citizens: Civil Society and the Mythology of the Shimin in Postwar Japan. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Chi, Myong Kwan. 2003. “Tokubetsu Intabyū: Kokusai Kyōdō Purojekuto toshite no Kankoku kara no Tsūshin [Letters from South Korea as international united project: special interview to Chi Myong Kwan].” Sekai September: 49-67.

____. 2005. Kyōkaisen o Koeru Tabi [Travel crossing the border]. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten.

Cho, Giun. 2006. “Zainichi chōsenjin to 1970 nendai no kankoku minshuka undō [Zainichi and the Korean democratization movement in the 1970s].” Language, Area and Cultural Studies No. 12: 197-217.

Chung, Kyung Mo. 2010. Sidaeŭi Pulch’imbŏn [Night watch of the era]. Seoul: Han’gyŏre Publisher.

Chung, Jae Joon. 2006. Aru “Zainichi” no Hansei: Kim Dae Jung Kyūshutsu Undō Shōshi [Half life of a Zainichi: A short history of the saving movement for Kim Dae Jung]. Tokyo: Gendaijinbun-sha.

Dewind, Adrian, and John Woodhouse. 1979. Persecution of Defense Lawyers in South Korea: Report of a Mission to South Korea in May 1979. Geneva: International Commission of Jurists.

ECC. 1976. Kankoku minsyuka touso siryosyu 1973~1976 [Collection of materials of the Korean democratization movement 1973~1976]. Tokyo: Sinkyo syupansya.

Hein, Laura, and Rebecca Jenninson, eds. 2010. Imagination without Borders: Feminist Artist Tomiyama Taeko and Social Responsibility. Ann Arbor: Center for Japanese Studies, the University of Michigan.

Human Rights Committee of NCCK. 1987. 1970 nyudae Mijuwha Undong: Kidokgyo Undong ul jungsimuro [Democratization movement in the 1970s: Christians’ Human Rights Movement] (five volumes). Seoul: NCCK.

Iijima, Makoto. 2003. “Kankoku Minsyuka no Dotei to Watashi [Democratization of South Korea and me].” Kyozo June: 13-22.

Kim, Dae Jung. 1973. “Kankoku Minshuka e no Michi [The way for Democratization of South Korea]” Sekai September: 102-122.

—. 2010. Kimdaejung chasŏjŏn [The Biography of Kim Dae Jung] Seoul: Samin.

Kim, Jung Ran. 2006. Ilbon’gun wianbu undongŭi chŏn’gaewa munjeinsige taehan yŏn’gu: chŏngdaehyŏbŭi hwaltongŭl chungsimŭro [A study of the development and the viewpoint of the “Comfort Women” issue in Korea: focusing on the Korean Council for the Women Drafted into Sexual Slavery by Japan]. Doctoral Dissertation, Department of Women’s Studies, The Graduate School of Ewha Womans University.

Kim, Tae Myung. 1986. “Zainichi Kankokujin Seijihan no jūgonen: Kakehashi toshite no Zainichi Kankokujin Seijihan [15 Years of Zainichi Korean Political Prisoners: Zainichi Korean political prisoners as the bridge],” Sekai June: 214-231.

The Committee to Save the Suh Brothers. 1992. Suh kun kyōdai o sukuu tame ni: kaihō gappon [To save Suh Brothers: the collection of the bulletins]. Tokyo: Kage Shobō.

Korea Democracy Foundation. 2008. Han’guk Minjuhwa Undongsa 1 [History of Korea democratization movement 1] Paju: Dolbegae.

____. 2009. Han’guk Minjuhwa Undongsa 2 [History of Korea democratization movement 2] Paju: Dolbegae.

____. 2010. Han’guk Minjuhwa Undongsa 3 [History of Korea democratization movement 3] Paju: Dolbegae.

Lee, Misook. 2012. “Kankoku Minshu ka Undōni okeru Chika Jōhō no Hasshin [Dissemination of underground information in the democratization movement of South Korea].” Contact Zone Vol. 5: 145-172.

Lie, John. 2008. Zainichi: Diasporic Nationalism and Postcolonial Identity. Berkeley: University of California Press.

McCormack, Gavan, and Mark Selden, eds. 1978. Korea, North and South: the deepening crisis. New York: Monthly Review Press.

Minaguchi, Kōzō. 1968. Anpo tōsō shi: hitotsu no undōronteki sōkatsu [The Anti-US-Japan Treaty movement: roundup of movement theory]. Tokyo: Shakai Shinpō.

Moon, Katharine H.S. 2012. Protesting America: Democracy and the U.S.-Korea Alliance. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Morris-Suzuki, Tessa. 2007. “Japan’s ‘Comfort Women’: It’s time for the truth (in the ordinary, everyday sense of the word).” Japan Focus, March 8, 2007.

Nakagawa, Nobuo. 1972. “1970 nendai no Kankoku Gakusei Undō [Korean Student Movement of the 1970s]” Sekai April: 190-199.

Nozaki, Yoshiko, and Mark Selden. 2009. “Japanese Textbook Controversies, Nationalism, and Historical Memory: Intra-national conflicts.” The Asia-Pacific Journal Vol 24-5-09, June 15.

Ōe Kenzaburo and Yasue Ryōsuke. 1984. “Sekai” no 40 nen: sengo o minaosu, soshite, ima [40 years of Sekai: reflection on the postwar period and today]. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten.

Oguma, Eiji. 2002. Minsyu to Aikoku: Sengo Nihon no Nasyonarizumu to Kokyosei [Democracy and Patriotism: Japan’s nationalism and the public sphere in the postwar period]. Tokyo: Shinyo-sha.

—. 2009a. 1968 vol.1: Wakamono tachi no Hanran to Sono Haikei [1968 vol. 1: The youth revolt and its background]. Tokyo: Shinyo-sha.

—. 2009b. 1968 vol.2: Hanran no Shuen to Sono Isan, [1968 vol. 2: the end of the youth revolt and its legacy]. Tokyo: Shinyo-sha.

Oh, Jae Shik. 2012. Naege Kkodŭro Tagaon Hyŏnjang [Presence appearing like flowers for me]. Seoul: Taehan’gidokkyosŏhoe.

Park, Hyung Gyu. 2010. Naŭi Midŭmŭn Kil wie Itta [My faith is on the street]. Paju: Changbi.

Sibuya, Sentaro. 1971. “Yakusha Kōki [Postscript by the translator],” Kim Chi Ha, Nagai Kurayami no Kanata ni [Far away in the long darkness]. Tokyo: Chuokoronsha: 270-273.

Shoji, Tsutomu. 2009. “Kankoku Minshukaundō to Nihonshimin no Kakawari [The Korean democratization movement and its relation to Japanese citizens],” “Chōsen o Mitsumete [By staring at Korea].” Kōrai Hakubutsukan: 27-89.

Sohn, Hak-kyu. 1989. Authoritarianism and Opposition in South Korea. London and New York: Routledge.

Steinhoff, Patrichia G. 2003. Shi e no ideorogī: Nihon Sekigunha [Ideology concerning death: Japan’s Red Army]. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten.

Suga, Hidemi. 2006. 1968. Tokyo: Chikuma-syobo.

Suh, Sung. 1994. Gokuchū 19 nen: Kankoku Seijihan no Tatakai [19 years in prison: the struggle of a Korean political prisoner]. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten.

Takahashi, Kunie. 1974. “Kisen Kankō o Kokuhatsu suru” [I’m denouncing sex tourism]. Sekai May: 144-148.

Takasaki, Sōji.1996. Kenshō: nikkan kaidan [Examination of talks between Japan and Korea]. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten.

Tanaka, Akira. 1975. “Kei to Henken to: ‘Kikan Sansenri’ Sōkan ni yosete [Respect and prejudice],” Sansenri 1: 142-149.

Tōdai hō Zenkyōtō ed. 1971. Kokuhatsu nyūkan taisei [Denunciation of the immigration system]. Tokyo: Aki Shobō.

Tomiyama, Taeko. 2009. Ajia o idaku [Embracing Asia]. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten.

Tsurumi, Shunsuke, and Kim Dalsoo. 1975. “Taidan: Undō ga umidasu mono [Talk: What is learned from Activism].” Sansenri 1: 12-31.

Tsurumi Shunsuke, Ueno Chizuko and Oguma Eiji. 2004. Senso ga Tsubusita Mono: Tsurumi Shunsuke ni Sengosedai ga Kiku [What the war destroyed: Postwar generation’s interviews with Tsurumi Shunsuke]. Tokyo: Shinyo-sha.

Wada, Haruki. 1975a. “Nikkanrentai no Shisō to Tenbō [Thought and prospect of Japan-Korea Solidarity].” Sekai November: 52-28.

—. 1975b. “Kim Chi Ha o Tasukerukai no imi [The meaning of the Committee to save Kim Chi Ha],” Sansenri 1: 52-61.

Wada, Haruki, Ishizaki Koichi, and the Sengo Gojunen Kokkai Ketsugi o Motomerukai, eds. 1996. Nihonwa shokuminchi shihai o do kangaete kitaka [How Japan has reflected on its colonial domination]. Tokyo: Nashinokisha.

Yonekura, Masakane. 1977. “Kankoku kara no Tsūshin o Enshutsu shite [Directing ‘Letters from South Korea’].” Sekai August: 342-246.

Yoshimatsu, Shigeru. 1986. “Zainichi Kankokujin Seijihan no jūgonen: Jūgonenkan kara miete kita mono [Fifteen years of Zainichi Korean Political Prisoners: from fifteen years’ experience].” Sekai June: 232-241.