(和訳はこちら)

If some extraterrestrial species were compiling a history of homo sapiens, they might well break their calendar into two eras: BNW (before nuclear weapons) and NWE, the nuclear weapons era. The latter era of course opened on August 6 1945, the first day of the countdown to what may be the inglorious end of this strange species, which attained the intelligence to discover effective means to destroy itself, but, so the evidence suggests, not the moral and intellectual capacity to control their worst instincts.

Day 1 of the NWE marked the success of Little Boy, a simple atomic bomb. On day 4, Nagasaki experienced the technological triumph of Fat Man, a more sophisticated design. Five days later came what the official Air Force history calls the “grand finale,” a 1000-plane raid – no mean logistical achievement – attacking cities and killing many thousands of people, with leaflets falling among the bombs proclaiming, in Japanese, “Your Government has surrendered. The war is over!” Truman announced the surrender before the last B-29 returned to its base.1

Those were the auspicious opening days of the NWE. As we now enter its 70th year, we should be contemplating with wonder that we have survived. We can only guess how many years remain.

Some reflections on these grim prospects were offered by General Lee Butler, former head of the U.S. Strategic Command (STRATCOM), which controls nuclear weapons and strategy. He writes that we have so far survived the NWE “by some combination of skill, luck, and divine intervention, and I suspect the latter in greatest proportion.”2

Reflecting on his long career in developing nuclear weapons strategies and organizing the forces to implement them efficiently, he describes himself ruefully as having been “among the most avid of these keepers of the faith in nuclear weapons.” But now, he continues, he realizes that it is his “burden to declare with all of the conviction I can muster that in my judgment they served us extremely ill.” And he asks “By what authority do succeeding generations of leaders in the nuclear-weapons states usurp the power to dictate the odds of continued life on our planet? Most urgently, why does such breathtaking audacity persist at a moment when we should stand trembling in the face of our folly and united in our commitment to abolish its most deadly manifestations?”3

General Butler describes the U.S. strategic plan of 1960 calling for automated all-out strike as “the single most absurd and irresponsible document I have every reviewed in my life.”4 The likely Soviet counterpart is probably even more insane. But it is important to bear in mind that there are competitors, not least among them the easy acceptance of threats to survival in ways that are almost too extraordinary to capture in words.

According to received doctrine in scholarship and general intellectual discourse, the prime goal of state policy is national security. There is ample evidence that the doctrine does not encompass security of the population. The record reveals that even the threat of instant destruction by nuclear weapons has not ranked high among the concerns of planners. That much was demonstrated early on, and remains true to the present moment.

In the early days of the NWE, the U.S. was overwhelmingly powerful and enjoyed remarkable security: it controlled the hemisphere, both oceans, and the opposite sides of both oceans. Long before the war it had become by far the richest country in the world, with incomparable advantages. Its economy boomed during the war, while other industrial societies were devastated or severely weakened. By the opening of the new era, the U.S. had about half of total world wealth and an even greater percentage of its manufacturing capacity. There was however a potential threat: ICBMs with nuclear warheads. The threat is discussed in the standard scholarly study of nuclear policies, carried out with access to high-level sources, by McGeorge Bundy, who was National Security Advisor during the Kennedy and Johnson presidencies.5

Bundy writes that “the timely development of ballistic missiles during the Eisenhower administration is one of the best achievements of those eight years. Yet it is well to begin with a recognition that both the United States and the Soviet Union might be in much less nuclear danger today if these missiles had never been developed.” He then adds an instructive comment: “I am aware of no serious contemporary proposal, in or out of either government, that ballistic missiles should somehow be banned by agreement.”

In short, there was apparently no thought of trying to prevent the sole serious threat to the US, the threat of utter destruction.

Could the threat have been prevented? We cannot of course be sure. It is not impossible, however. The Russians were far behind in industrial development and technological sophistication and in a far more threatening environment. Hence they were much more vulnerable to such weapons systems than the US. There might have been opportunities to explore these possibilities, but in the extraordinary hysteria of the day they could hardly have even been perceived. And it was extraordinary. The rhetoric of such central documents as NSC 68 is quite shocking, even discounting Acheson’s injunction that it is necessary to be “clearer than truth.”

One suggestive indication of possible opportunities is a remarkable proposal by Stalin in 1952, offering to allow Germany to be unified with free elections on condition that it not join a hostile military alliance – hardly an extreme condition in the light of the history of the past half century, when Germany alone had practically destroyed Russia twice, exacting a terrible toll.

Stalin’s proposal was taken seriously by the respected political commentator James Warburg, but apart from him it was mostly ignored or ridiculed. Recent scholarship has begun to take a different view. The bitterly anti-Communist Soviet scholar Adam Ulam takes the status of Stalin’s proposal to be an “unresolved mystery.” Washington “wasted little effort in flatly rejecting Moscow’s initiative,” he writes, on grounds that “were embarrassingly unconvincing.” The political, scholarly, and general intellectual failure leaves open “the basic question,” Ulam writes: “Was Stalin genuinely ready to sacrifice the newly created German Democratic Republic (GDR) on the altar of real democracy,” with consequences for world peace and for American security that could have been enormous?6

Reviewing recent research in Soviet archives, one of the most respected Cold War historians, Melvyn Leffler, observes that many scholars were surprised to discover that “[Lavrenti] Beria — the sinister, brutal head of the secret police – propos[ed] that the Kremlin offer the West a deal on the unification and neutralization of Germany,” agreeing “to sacrifice the East German communist regime to reduce East-West tensions” and improve internal political and economic conditions in Russia – opportunities that were squandered in favor of securing German participation in NATO.7

Under the circumstances, it is not impossible that agreements might have been reached that would have protected the security of the American population from the gravest threat on the horizon. But the possibility apparently was not considered, a striking indication of how slight a role authentic security plays in state policy.

That conclusion has been underscored repeatedly in the years that followed. When Nikita Khrushchev took control in 1953, after Stalin’s death, he recognized that Russia could not compete militarily with the US, the richest and most powerful country in history, with incomparable advantages. If Russia hoped to escape its economic backwardness and the devastating effect of the war, it would therefore be necessary to reverse the arms race. Accordingly, Khrushchev proposed sharp mutual reductions in offensive weapons. By 1960, U.S. intelligence verified huge cuts in active Soviet military forces, with radical reduction of light bomber units, naval air fighter-interceptors, aircraft, and manpower, including withdrawal of more than 15,000 troops from East Germany. Khruschev called on the U.S. to undertake similar reductions of the military budget and in military forces in Europe and generally, and to move towards further reciprocal cuts. President Kennedy privately discussed such possibilities with high Soviet officials, but rejected the offers, instead turning to rapid military expansion, even though the U.S. was already far in the lead. William Kaufmann, a former top Pentagon aide and leading analyst of security issues, describes the U.S. failure to respond to Khrushchev’s initiatives as, in career terms, “the one regret I have.”8

The prominent realist international relations scholar Kenneth Waltz observes that the Kennedy administration “undertook the largest strategic and conventional peace-time military build-up the world has yet seen…even as Khrushchev was trying at once to carry through a major reduction in the conventional forces and to follow a strategy of minimum deterrence, and we did so even though the balance of strategic weapons greatly favored the United States.”9

Once again, Washington chose to harm national security while enhancing state power.

|

A U-2 reconnaissance photograph of Cuba, showing Soviet nuclear missiles, their transports and tents for fueling and maintenance. |

The Soviet reaction was to place missiles in Cuba in October 1962 to try to redress the balance at least slightly. The move was also motivated by Kennedy’s terrorist campaign against Cuba, which was scheduled to lead to invasion that month, as Russia and Cuba may have known. The ensuing “missile crisis” was “the most dangerous moment in history,” in the words of historian Arthur Schlesinger, Kennedy’s advisor and confidant. As the crisis peaked in late October, Kennedy received a secret letter from Khrushchev offering to end it by simultaneous public withdrawal of Russian missiles from Cuba and U.S. Jupiter missiles from Turkey – the latter obsolete missiles, for which a withdrawal order had already been given because they were being replaced by far more lethal Polaris submarines. Kennedy’s subjective estimate was that if he refused, the probability of nuclear war was 1/3 to ½ — a war that would have destroyed the northern hemisphere, President Eisenhower had warned. Kennedy refused. It is hard to think of a more horrendous decision in history. And worse, he is greatly praised for his cool courage and statesmanship.10

Ten years later, Henry Kissinger called a nuclear alert in the last days of the 1973 Israel-Arab war. The purpose was to warn the Russians not to interfere with his delicate diplomatic maneuvers, designed to ensure an Israeli victory, but a limited one, so that the U.S. would still be in control of the region unilaterally. And the maneuvers were delicate. The U.S. and Russia had jointly imposed a cease-fire, but Kissinger secretly informed Israel that they could ignore it. Hence the need for the nuclear alert to frighten the Russians away. Security of the population had its usual status.11

|

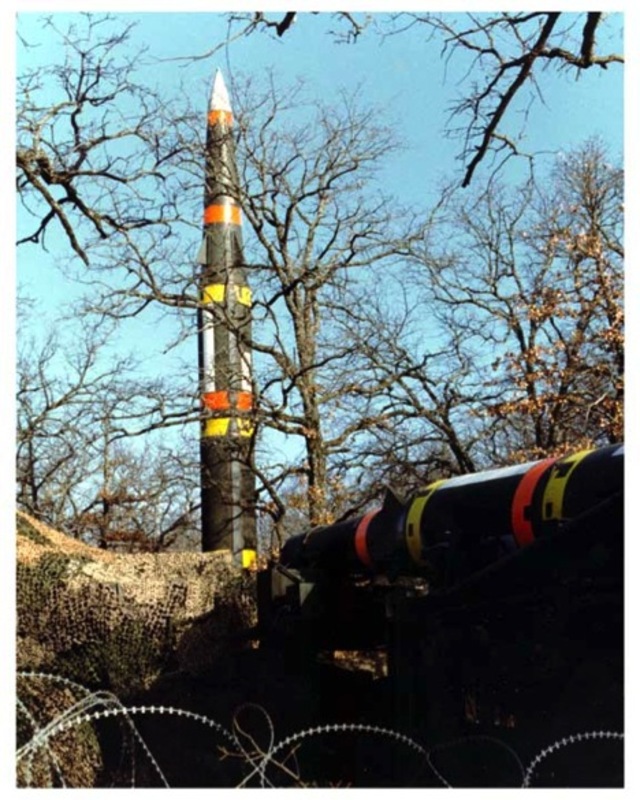

US Pershing Missile |

Ten years later the Reagan administration launched operations to probe Russian air and naval defenses, simulating attacks and even a full-scale release of nuclear weapons, along with a high-level nuclear alert intended for the Russians to detect. These actions were undertaken at a very tense moment. Pershing II strategic missiles were being deployed in Europe, with a 5-10 minute flight time to Moscow, “roughly how long it takes some of the Kremlin’s leaders to get out of their chairs, let alone to their shelters,” according to a CIA memo. In March 1983, Reagan announced the SDI (star wars) program, which the Russians understood to be effectively a first-strike weapon, a standard interpretation of missile defense on all sides. And other tensions were rising. Naturally these actions caused great alarm in Russia, which unlike the U.S. was quite vulnerable and had repeatedly been invaded and virtually destroyed. That led to a major war scare in 1983. Newly released archives reveal that the danger was even more severe than had been previously assumed. A very detailed recent study based on extensive U.S. and Russian intelligence records reaches the conclusion that “The War Scare Was for Real,” and that U.S. intelligence may have underestimated Russian concerns and the threat of a Russian preventive nuclear strike. The exercises almost became “a prelude to a preventive nuclear strike,” according to an account in the Journal of Strategic Studies.12

It was even more dangerous than that, so we learned a year ago, when the BBC reported that right in the midst of these world-threatening developments, Russia’s early-warning systems detected an incoming missile strike from the United States, sending the highest-level alert. The protocol for the Soviet military was to retaliate with a nuclear attack of its own. The officer on duty, Stanislav Petrov, decided to disobey orders and not to report the warnings to his superiors. He received an official reprimand. And thanks to his dereliction of duty, we’re alive to talk about it.13

Security of the population was no more a high priority for Reagan planners than for their predecessors. So it continues to the present, even putting aside the numerous near catastrophic accidents, many reviewed in Eric Schlosser’s chilling study of the topic.14 It is hard to contest General Butler’s conclusions.

The record of post-Cold War actions and doctrines is also hardly reassuring. Every self-respecting President has to have a Doctrine. The Clinton Doctrine was encapsulated in the slogan “multilateral when we can, unilateral when we must.” In congressional testimony, the phrase “when we must” was explained more fully: the U.S. is entitled to resort to “unilateral use of military power” to ensure “uninhibited access to key markets, energy supplies and strategic resources.”15

Meanwhile Clinton’s STRATCOM produced an important study entitled Essentials of Post-Cold War Deterrence, issued well after the Soviet Union had collapsed and Clinton was carrying forward the Bush I program of expanding NATO to the East in violation of promises to Gorbachev – with reverberations to the present.16

The STRATCOM study is concerned with “the role of nuclear weapons in the post-Cold War era.” One central conclusion is that the U.S. must maintain the right of first-strike, even against non-nuclear states. Furthermore, nuclear weapons must always be available, at the ready, because they “cast a shadow over any crisis or conflict.” They are constantly used, just as you’re using a gun if you aim it but don’t fire when robbing a store, a point that Daniel Ellsberg has repeatedly stressed. STRATCOM goes on to advise that “planners should not be too rational about determining…what the opponent values the most,” all of which must be targeted. “[I]t hurts to portray ourselves as too fully rational and cool-headed…That the US may become irrational and vindictive if its vital interests are attacked should be a part of the national persona we project.” It is “beneficial [for our strategic posture] if some elements may appear to be potentially `out of control’,” and thus posing a constant threat of nuclear attack – a severe violation of the UN Charter, if anyone cares.

Not much here about the noble goals constantly proclaimed. Or for that matter about the obligation under the NPT to make “good faith” efforts to eliminate this scourge of the earth. What resounds, rather, is an adaptation of Hilaire Belloc’s famous couplet about the gatling gun: “Whatever happens we have got, The Atom Bomb and they have not” – to quote the great African historian Chinweizu.

Clinton was followed by Bush II, whose broad endorsement of preventive war easily encompasses Japan’s attack in December 1941 on military bases in two U.S. overseas possessions, at a time when Japanese militarists were well aware that B-17 Flying Fortresses were being rushed off the assembly lines and deployed to these bases with the intent “to burn out the industrial heart of the Empire with fire-bomb attacks on the teeming bamboo ant heaps of Honshu and Kyushu.” So the plans were described by their architect, Air Force General Chennault, with the enthusiastic approval of President Roosevelt, Secretary of State Cordell Hull, and Army Chief of Staff General George Marshall.17

Then comes Obama, with pleasant words about abolition of nuclear weapons combined with plans to spend $1 trillion on the nuclear arsenal in the next 30 years, a percentage of the military budget “comparable to spending for procurement of new strategic systems in the 1980s under President Ronald Reagan,” according to a study of the Monterey Institute of International Studies.18

Obama has also not hesitated to play with fire for political gain. Take for example the capture and assassination of Osama bin Laden by Navy Seals. Obama brought it up with pride in an important speech on national security in May 2013. It was widely covered, but one crucial paragraph was ignored.19

Obama hailed the operation but added that it cannot be the norm. The reason, he said, is that the risks “were immense.” The Seals might have been “embroiled in an extended firefight,” but even though, by luck, that didn’t happen “the cost to our relationship with Pakistan and the backlash among the Pakistani public over encroachment on their territory was…severe.”

Let us now add a few details. The Seals were ordered to fight their way out if apprehended. They would not have been left to their fate if “embroiled in an extended firefight.” The full force of the U.S. military would have been used to extricate them. Pakistan has a powerful military, well trained and highly protective of state sovereignty. It also of course has nuclear weapons, and Pakistani specialists are concerned about penetration of the security system by jihadi elements. It is also no secret that the population has been embittered and radicalized by the drone terror campaign and other U.S. policies.

While the Seals were still in the Bin Laden compound, Pakistani chief of staff Ashfaq Parvez Kayani was informed of the invasion and ordered the military to confront any unidentified aircraft, which he assumed would be from India. Meanwhile in Kabul, General David Petraeus was prepared to mobilize U.S. warplanes to respond if Pakistanis scrambled their fighter jets.20

As Obama said, by luck the worst didn’t happen, and it could have been quite ugly. But the risks were faced without noticeable concern. Or subsequent comment.

General Butler was quite correct to observe that it is a near miracle that we have escaped destruction so far. And the longer we tempt fate, the less likely it is that we can hope for divine intervention to perpetuate the miracle.

*An earlier version appeared at TomDispatch.com, “Tomgram: Noam Chomsky, How Many Minutes to Midnight? Hiroshima Day 2014” Aug. 5 2014.

Noam Chomsky is a linguist, philosopher, political analyst and activist. Institute Professor emeritus in the Department of Linguistics and Philosophy at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, his recent books are Hegemony or Survival, Failed States, Power Systems, Occupy, and Hopes and Prospects. His latest book, Masters of Mankind, will be published soon by Haymarket Books, which is also reissuing twelve of his classic books in new editions over the coming year. An archive of his work resides at chomsky.info.

Recommended citation: Noam Chomsky, “How Many Minutes to Midnight? On the Nuclear Era and Armageddon,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 11, Issue 33, No. 1, August 18, 2014.

Notes

1 Wesley F. Craven and James L. Cate, eds., The Army Air Forces in World War II, U. of Chicago Press, 1953, Vol. 5, pp. 732-33. Makoto Oda, “The Meaning of ‘Meaningless Death,” Tenbo, January 1965, translated in the Journal of Social and Political Ideas in Japan, Vol. 4 (August 1966), pp. 75-84. See Noam Chomsky, “On the Backgrounds of the Pacific War,” Liberation, September-October, 1967, reprinted in American Power and the New Mandarins, Pantheon 1969.

2 Cited by Stephen Shapin, “How Worried Should We Be?,” London Review of Books, “Vol. 36 No. 2, 23 January 2014. General Lee Butler, letter to Bill Graham, Chair, Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs and International Trade, House of Commons, Ottawa, July 1998.

3 Butler, International Affairs, 82.4, 2006.

4 Shapin, op. cit.

5 Bundy, Danger and Survival: Choices About the Bomb in the First Fifty Years. Random House, 326.

6 James Warburg, Germany: Key to Peace (Harvard, 1953), 189f. Adam Ulam, Journal of Cold War Studies 1, no. 1 (winter 1999).

7 Leffler, Foreign Affairs, July-August 1996.

8 Raymond L. Garthoff, “Estimating Soviet Military Force Levels,” International Security 14:4, Spring 1990. Fred Kaplan, Boston Globe, Nov. 29, 1989.

9 Kenneth Waltz, PS: Political Science & Politics, December 1991.

10 Sheldon Stern, The Cuban Missile Crisis in American Memory: Myths versus Reality, Stanford U. Press, 2012. For further details and sources see Chomsky, Hegemony or Survival, Metropolitan, 2003, chap. 4.

11 Noam Chomsky and Irene Gendzier, “Exposing Israel’s Foreign Policy Myths: the Work of Amnon Kapeliuk,” Jerusalem Quarterly, Institute of Jerusalem Studies, no 54, summer 2013. To appear as introduction to Amnon Kapeliuk, The 1973 War: the Conflict that Shook Israel, I.B. Tauris; English translation by Mark Marshall of Hebrew original, “Lo ‘mehdal’: ha-mediniut she-holicha le-milhama” (“Not `omission’: the policy that led to war”), Amikam (Tel Aviv) 1975.

12 Benjamin B. Fischer, “A Cold War Conundrum: The 1983 Soviet War Scare,” Summary , last updated July7, 2008. Dmitry Dima Adamsky (2013) The 1983 Nuclear Crisis – Lessons for Deterrence Theory and Practice, Journal of Strategic Studies, 36:1, 4-41, DOI: 10.1080/01402390.2012.732015. See also the documents released by the National Security Archive.

13 BBC News Europe, 26 September 2013.

14 Schlosser, Command and Control: Nuclear Weapons, the Damascus Accident, and the Illusion of Safety, Penguin, 2013.

15 President Bill Clinton, Speech before the UN General Assembly, Sept. 27, 1993; Secretary of Defense William Cohen, Annual Report to the President and Congress: 1999 (Washington, DC: Department of Defense, 1999).

16 “Essentials of Post-Cold War Deterrence,” declassified portions reprinted in Hans Kristensen, Nuclear Futures: Proliferation of Weapons of Mass Destruction and US Nuclear Strategy, British American Security Information Council, Appendix 2, Basic Research Report 98.2, March 1998.

17 Michael Sherry, The Rise of American Airpower (Yale, 1987).

18 Jon B. Wolfstahl, Jeffrey Lewis, and Marc Quint, The Trillion Dollar Nuclear Triad: US Strategic Nuclear Modernization over the Next Thirty Years, James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies, Monterey Institute of International Studies, Monterey CA, Jan. 2014. Possibly an underestimate; see Tom Collina, “Nuclear Costs Undercounted, GAO Says,” Arms Control Today, July/August 2014.

20 Jeremy Scahill, Dirty Wars, Nation Books, 2013, 450, 443.