Japanese translation is available

Two years after the Fukushima nuclear crisis began two media experts dissect how it has been covered by the media in Japan. Uesugi Takashi is a freelance journalist and author of several books on the Fukushima crisis, including Terebi Wa Naze Heiki De Uso Wo Tsukunoka? (Why does television tell so many lies?). He is also one of the founders of The Free Press Association of Japan (www.fpaj.jp), which attempts to offer an alternative to Japan’s press club system. Ito Mamoru, is professor of media and cultural studies at Waseda University and author of Terebi Wa Genpatsu Jiko Dou Tsutaetenoka? (How did television cover the nuclear accident?).

Uesugi-san, is it true that you have been banned from the media because of your comments on Fukushima?

Until two years ago I had regular programs on television and also radio. Now the only regular radio that I do is Tokyo FM. Right now I don’t do TBS radio (where he had a regular slot). I have no hope of appearing on NHK or on the commercial networks. I used to be a regular or semi-regular on several TV shows but now not even one. I was also a regular guest on radio shows, but no more.

The electric utilities in Japan are major TV sponsors. I found this out two years ago. They spent 70~88.8 billion yen on advertising that year, ahead of Panasonic with 70 billion yen and Toyota at 50 billion yen. When I started claiming that this amounted to bribery of the media by TEPCO, I was no longer asked to appear on radio shows.

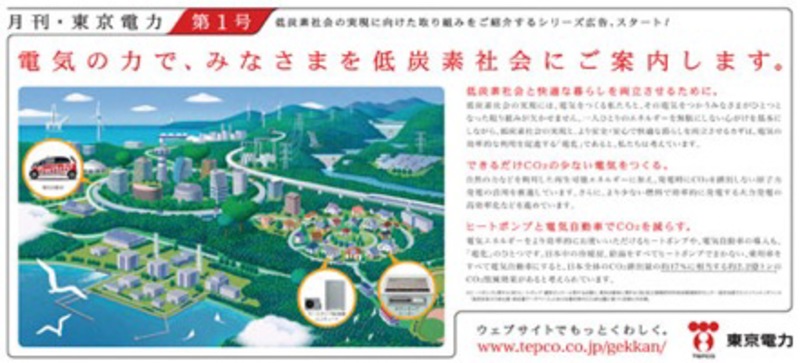

|

The bright future portrayed by Tepco |

Ito-san, tell us about your research. You surveyed Japanese television coverage of the first week of the nuclear crisis and found that only a single anti-nuclear expert had appeared, right?

That’s right. Before the disaster, TBS had a history of inviting experts from the (anti-nuclear) citizens’ nuclear information center; the director of TBS had personal contact with them. But they also always invited pro-nuclear people from the so-called nuclear village, as balance. After the crisis, Fuji TV had a guy called Fujita Yuko, who has always been anti-nuclear, but only once. On the afternoon of March 11th he said there was the possibility of a meltdown. He was never allowed back on screen.

Some foreign correspondents believe that the government and the Japanese media had a duty to avoid triggering panic in the week after March 11. It was fine for the foreign media, perhaps, to sometimes report sensationally, but local journalists had a very heavy responsibility. What’s your take on this?

Ito: When the Fukushima Daiichi number one reactor exploded, a television camera for Fukushima Central Television caught the image and broadcast it two minutes later. The reporters were themselves afraid about what was happening inside, but there was no way that the head of the station couldn’t not report this. In other words, when journalists have information, even without knowing what it really means, it’s their responsibility to report it. They also reported which way the wind was blowing. Did Fukushima residents panic when they heard this video clip? No. Fukushima Central TV repeatedly asked the big Japanese broadcasting networks to report this explosion quickly. But it took an hour and ten minutes before it was reported on Nihon TV, Fuji TV and NHK. And they all reported it at the same time

They are completely different broadcasting companies so how did they do that, reporting at the same time?

Ito: I don’t think it was a coincidence, but I can’t prove that. In Fukushima, all the networks were monitoring local broadcasts and they would have known about the explosion report. They have some kind of collective agreement on what to cover. When the three TV stations finally aired the footage at the same time, they had almost the same explanation (for the blast): it was a result of artificially releasing the vapor from a squib valve.

Uesugi: There is an image of the first reactor explosion that ran in the New York Times and another on the BBC. An hour and ten minutes after the explosion, the image suddenly disappeared from Japan, so the Japanese people couldn’t get access to it for over a year on the mainstream media. You could still see it on YouTube, but not on TV.

I turned to the European Broadcasting Union, which had bought the rights for the coverage. I insisted that on humanitarian grounds the residents should have the information and then decide for themselves what to do after seeing the image. As soon as it was reported, the commercial broadcasting companies in Japan demanded that I remove that image from my homepage. It has become taboo in Japan.

Ito: Really, the government and the media were the ones who actually caused the panic. In a crisis like this, they feel the need to speak in a single voice. But when the government and the media together report that “everything is safe”, it has the opposite effect of making people worry. The government should distribute alternative information and admit there are a lot of things that are not clear. The biggest problem during the nuclear crisis was that there wasn’t that kind of information environment.

Uesugi: It was not ordinary residents, but the government, METI, and the mass media that were panicking. Allowing different views in the media is healthy. When there are different views you have to think and can avoid panic. That’s why I called the Prime Minister’s Residence during the crisis and asked them to let in foreign journalists, and freelance reporters for the Internet and magazines. There would be different types of information available and no panic. The press clubs were causing panic.

Ito: Around March 15th or 16th the central government directly asked Fukushima City if they wanted to evacuate the population of 400,000. The city refused, but the media decided not to report this because they thought it would cause panic. The government once considered extending the evacuation zone as far as Fukushima City. Then later, when the 20 millisieverts issue rose (the government upped the annual limit of “acceptable” radiation limits in schools from 1 – 20 MSv) they didn’t evacuate young children who should most definitely have been taken out of Fukushima and Koriyama cities.

Why do you think journalists for the mainstream media in Japan stayed out of the 20-km evacuation zone, despite the pressure for scoops about what was going on there?

Ito: One of my friends once said, “Japan’s journalism is compliance journalism. Each channel tells the people that it is safe to stay near the area while they tell their own employees that it’s forbidden to report within 30km of the plant because it is dangerous. There is a real double standard, but employees cannot go against that rule.

Uesugi: Members of the press club and the government were openly saying: “My wife’s hometown is in Kyushu so I sent her back there” or: “I let my child go to Singapore.” They were doing this from March 15th. But as Ito-san has said, on TV and in the newspapers, they were saying that everything was safe. Even among politicians, there were some who sent their families out of Japan.

Looking back, what are the key mistakes made by the Japanese media and the foreign media?

Ito: I think the British newspaper, The Sun, carried some awful reports, very sensational. Some of the foreign press exaggerated the crisis. We have to look at differences. There is a huge difference between German TV and Japanese TV for example. In Japan, scientists who come on TV work for universities and are naturally close to the government. In Germany, more and more scientists collect independent scientific knowledge and get involved with anti-nuclear power movements or the Green Party.

In Japan, the organization has too much power and this is getting worse after 3. 11. There is no freedom of speech inside the mainstream media. There are many people who want to speak out and who know about what is going on, but they are censored.

Uesugi: I think the nuclear sensationalism is the fault of the Japanese government and the press clubs for not letting the foreign media into their press conferences, and for not making their reports accurate enough. I think the foreign media did better than the Japanese media, in the sense that they shared different voices. For example the German and Norwegian media were among the first to report the radiation map. The Washington Post was the first to show the diagram of the meltdown and foreign journalists reported inside the evacuation areas.

Ito: In a transnational crisis like this, even scientists have very different views onwhat should be done. The media should provide scientific data to the people and the government, and help make more efficient decisions. But the media have not learnt any skills on how to use communication technology and simply assumed it was safe when the government said it was safe, just like in the bad old days.

Uesugi: We have to be modest about the truth and admit which media was wrong and which was right, otherwise journalists end up doing the same thing as the government: making a mistake, not admitting the mistake and hiding the mistake. Unless this system is improved, I don’t think anything will change. In the end, people who are not told the truth will not trust the media. We have to make a proper accident investigation and confront our own mistakes.

Recommended citation: David McNeill, “Truth to Power: Japanese Media, International Media and 3.11 Reportage,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol 11, Issue 10, No. 3, March 11, 2012.”

David McNeill is the Japan correspondent for The Chronicle of Higher Education and writes for The Independent and Irish Times newspapers. He covered the nuclear disaster for all three publications, has been to Fukushima ten times since 11 March 2011, and has written the book Strong in the Rain (with Lucy Birmingham) about the disasters. He is an Asia-Pacific Journal coordinator.

Articles on related subjects

• Mainichi Shimbun, The Black Box of Japan’s Nuclear Power here

• Reporters Without Borders on Discrimination Against Freelance Journalists in Japan here

• Makiko Segawa, After The Media Has Gone: Fukushima, Suicide and the Legacy of 3.11 here

• Nicola Liscutin, Indignez-Vous! ‘Fukushima,’ New Media and Anti-Nuclear Activism in Japan here

• Philip J. Cunningham, Japan Quake Shakes TV: The Media Response to Catastrophe here

• Tony McNicol and David McNeill, Is Press Freedom Being Eroded in Japan? here

• David McNeill, Freedom of the Press U.S. Style on Okinawa here