Introduction

A Chinese woman said that when her children first started school, she initially had difficulty getting information about their schoolwork as she was not listed on the registration document. ‘They wouldn’t accept me as the ‘real’ mother because I wasn’t listed [on the family registry].’

An American man, who remarried following his wife’s death, said his family had the unique situation of having three different ‘registrations’. Separate family registries for his daughter and second wife, and separate registration as an [sic] foreign resident for himself. ‘It was really strange that my daughter was listed as the head of household when she wasn’t even in school’.

A Korean woman, herself born in Japan, reported their landlord at first did not believe she and her husband were really married. ‘We had to go as far as showing our marriage certificate to prove we weren’t ‘living in sin’.1 (Swenson undated).

The three cases above exemplify the problems encountered by multinational families2 in Japan.3

The genesis of these unusual situations can be traced to the legislative intertwining of family and nationality in Japan. In short, legal status as Japanese (Japanese nationality) is determined by entry (nyūseki) into the Family Registration System (koseki seido). This legal structure creates numerous hindrances and encumbrances because it fails to keep up with and address the changes and diversification of what constitutes a ‘family’ in Japan. As I explain below, the present system, even with these recent changes to residency laws, is inadequate for alleviating such problems in a context of rapid change.

From 9 July 2012 a ‘new residency management system’ (zairyū kanri seido) was introduced in Japan. The amendments promise to improve administrative procedures and remove impediments, like those stated above, and represent some of the most significant changes to the population management of foreign residents in over sixty years. This is welcome news. However, the changes apply to only part of what, in essence, is an elaborate system of registries that are complexly interconnected.

Although it will take some time to fully understand the effects of these recent modifications, my purpose here is to discuss these developments in the broader context of legal and administrative processes that identify, manage and define the population of Japan. I argue that the 2012 changes, whilst a positive step forward, fall short of what is necessary to adequately and appropriately address the diverse and multifaceted population of residents living in Japan today.

The Changes

There are two main structural modifications in the 9 July changes. Firstly, the old ‘Alien Registration System’ (gaikokujin tōrokuseido) has been replaced by a ‘new residency management system’ (zairyū kanri seido). Secondly, residents with foreign nationality are now required to register locally on the Resident Registration (jūminhyō) that is administered by the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communication. These changes do not affect foreign nationals staying less than 3 months, those with temporary visitor status or ‘diplomat’ or ‘official’ status, special permanent residents and persons with no resident status (Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communication 2011a).

With regard to the first change, the Immigration Bureau of Japan’s (Hōmushō Nyūkoku Kanrikyoku) homepage (Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communication undated) describes four modifications resulting from the introduction of the new residency management system:

- The issuing of a resident card (zairyū kaado).

A resident card will be issued to mid- to long-term residents when granted permission pertaining to residence, such as landing permission, permission for change of resident status and permission for extension of the period of stay.

2. The period of stay will be extended to a maximum of 5 years (instead of the previous 3 years).

By changing the maximum period of stay to ‘5 years,’ the period of stay set for each resident status will be modified.

3. The re-entry permit system will be changed.

Foreign nationals in possession of a valid passport and resident card who will be re-entering Japan within 1 year (2 years for Special Permanent Residents) of their departure to continue their activities in Japan will, in principle, not be required to apply for a re-entry permit. (This is called a special re-entry permit).

4. The alien registration system will be abolished.

When the new residency management system goes into effect, the alien registration system will be abolished.

The introduction of the zairyū kanri seido has meant the scrapping of an over sixty year old Alien Registration System (gaikokujin tōroku seido) first introduced under the Alien Registration Act (gaikokujin tōrokurei) during the postwar period on 2 May 1947.

The second structural change involves the Basic Resident Registration Act (jūmin kihon daichō seido). This Act requires residents in a municipality to register and to notify the mayor of any change of address. Until the 9 July changes, the Act was only applicable to Japanese nationals, but now applies to foreign residents as well. The Bureau states that ‘[t]he new residency management system will be applied to all foreign nationals residing legally in Japan for the mid- to long-term with resident status under the Immigration Control Act’. This is perhaps the greatest reform to this system since the introduction of the Resident Registration Law enacted in 1951.

Context and Background

Up until 9 July 2012 residents in Japan were bureaucratically and administratively divided into Japanese nationals and foreign nationals through three systems of registration: Alien Registration (gaikokujin tōroku), Resident Registration (jūminhyō) and Family Registration (koseki). Alien registration and resident registration emerged in the post-war era, but the modern koseki was promulgated much earlier and forms the basis upon which the other laws were constructed. Foreigners were registered on the Alien Registry and Japanese nationals on the other two registries. In order to fully comprehend the structural changes above, a basic understanding of the historical context of these three registration systems is required. The changes are to Alien Registration (gaikokujin tōroku) and the Resident Registration (jūminhyō) introduced when Japan was under Allied occupation. However, the context in which these laws are embedded has a much longer history that is connected to the more fundamentally ingrained system of family registration (koseki).

The legislative intertwining of family registration and Japanese legal status mentioned above is historical and entrenched. The modern koseki (jinshin koseki) was enacted at the beginning of the Meiji Period in 1872 and was initially the only legislation that defined status as Japanese (see Chapman 2011). This definition was embedded in the ideology of the ie seido (family system) based on traditional notions of Japanese society and resurrected in the construction of Japan as a modern nation. Status as Japanese was legally and ideologically defined through membership of a state-recognised household or family. The legal codes for legislating Japanese nationality (kokuseki) were introduced later in 1899 under the Nationality Law (kokusekihō) but were secondary to registration on the koseki. Japanese nationality was made accessible only to those who held koseki registration creating an indelible connection between family registration and nationality. By retaining primacy over kokuseki in defining status as a Japanese national, the koseki is legislatively more powerful. Moreover, the koseki legally and ideologically prioritises the family over the individual as the fundamental social unit in Japanese society and retains the legacy of a system that historically assumes all family members possess Japanese status/nationality. A foreign national cannot enter the koseki until they naturalise as Japanese and, as a part of that process, they are expected to annul any other nationality they hold.4

The ‘Alien Registration System’ (gaikokujin tōrokuseido) and Resident Registration (jūminhyō) that are the foci of the 2012 changes were introduced in the post-war period and represent a contraction of the parameters of Japanese legal status. To understand this we need to go back to the beginning of the Meiji Period and the promulgation of the jinshin koseki. Its introduction led to the inclusion of the inhabitants of the Ryūkyū Islands, the indigenous Ainu and the former Burakumin and Hinin communities within the parameters of legal Japanese status. These groups were differentiated from the majority and marginalized under Tokugawa registries, but their inclusion meant, legally at least, that they were Japanese. However, socially this was not the case and, despite their bureaucratic and legal inclusion, the members of these communities for the most part have occupied an ambivalent position in Japanese society..

During imperial expansion and the colonization of the Korean peninsula, Taiwan and Manchukuo, there was a fundamental shift as the definition of Japanese legal status was further expanded through the koseki.5 As Japanese sovereign territory expanded, so did the legal parameters of Japanese status. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries Japanese legal status was granted to Korean (Chōsenjin), Taiwanese and Chinese (in the puppet state of Manchukuo) subjects registered on gai’chi koseki (outer territory family registers). Prior to this, status as Japanese was limited to subjects with a honseki (principal location of registration) located within Japan proper (nai’chi). The expansion and creation of gai’chi registers meant that millions of colonial subjects were now legally considered to have Japanese status (nihon kokumin). By 1945 there were over 2 million former Korean, 28,000 Taiwanese and 31,000 Chinese (Vasishth 1997:132) colonial subjects living in Japan proper.

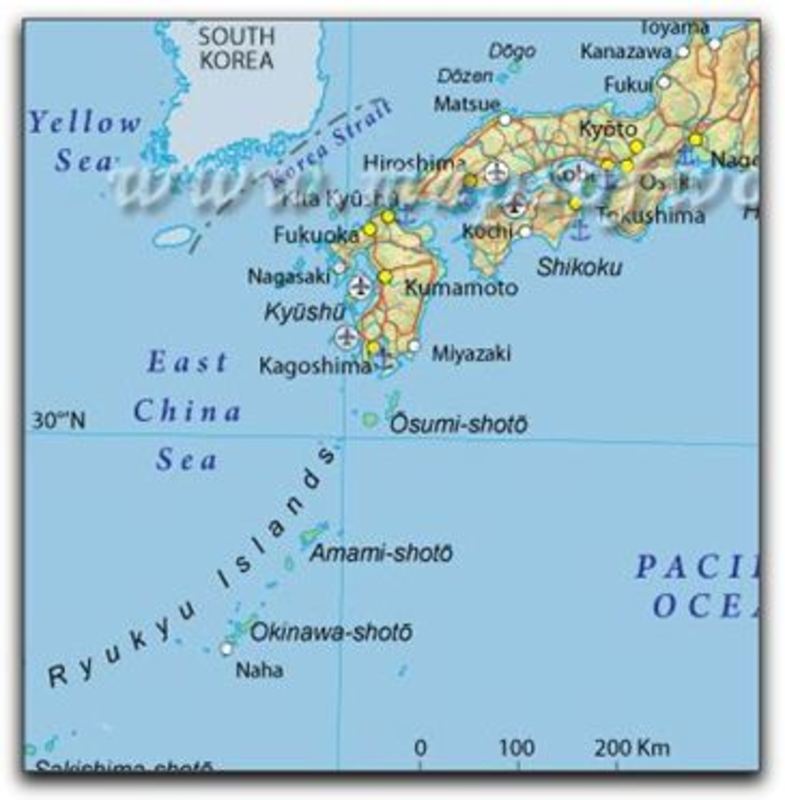

At the end of the Second World War, during the Allied Occupation, despite still possessing legal status as Japanese, an Order was issued on 13 March 1946 requesting Taiwanese, Chōsenese and those with principal registers located south of the 30 degree north latitude (see Figure 1 below) living in Japan to register as non-Japanese.6 The order was issued in the context of a previous memorandum from the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP) that advised the repatriation of ‘non-Japanese’ to their respective homelands (SCAPIN 224 1945). This was followed by the 1947 Alien Registration Order (gaikokujin tōroku rei) implemented on 2 May 1947, the day before the implementation of the 1947 constitution.7

The Alien Registration Order was followed by the Alien Registration Law (gaikokujin tōrokuhō) five years later on 28 April 1952.8 The implementation of this Law meant that over 600,0009 former colonial subjects living in Japan officially lost their legal status as Japanese and had to register as ‘aliens’/foreigners (gaikokujin) (for more on this see Morris-Suzuki 2011). A little later, in the year after the 1965 ROK – Japan Normalization Treaty was ratified, former colonial subjects, their children and grandchildren, who applied for South Korean nationality by January 1971 could receive permanent residence. As a result 323,197 Koreans became permanent residents. Applicants at this stage were required to submit certificates proving they were South Korean nationals. In 1982 the category ‘exceptional permanent residence’ was created for the remaining Korean population that were not required to demonstrate their South Korea nationality, some 268,178 people (see Ryang 1997:5). This treaty-based residency certificate (kyotei eijyū shikaku) was to be revisited in 1991. On 1 November 1991 under a Special Immigration Law (nyūkan tokureihō) a Special Permanent Resident category was introduced which included South and North Koreans as well as Taiwanese. This category offered some limited privileges over and above other permanent residents but did not confer citizenship.

The Alien Registration Law was also the first legislation that decreed the fingerprinting of foreign residents in Japan. Under this law, foreign nationals residing in Japan for three months or longer were required to register their details at a local ward office where they lived. They were also required to carry an Alien Registration Card (gaikokujin tōroku shōmeisho) at all times or risk punitive fines and/or imprisonment.10

Concerns and Issues

The first structural change in the 2012 legislation involves the scrapping of the Alien Registration Law and the Alien Registration Card (gaikokujin tōrokuhō shōmeisho). Although this is an improvement and certainly is welcome, the reality is that non-Japanese nationals residing in Japan are still expected to carry an identification card (zairyū kaado) which continues to attract penalties if the holder cannot produce it when requested by the appropriate authority. For special permanent residents (tokubetsu eijūsha) there is now a Special Permanent Residency Card (tokubetsu eijūsha shōmeisho). The retention of this policing element in this aspect of the legislation is not surprising given the increased global concerns over the threat of terrorism sparked by the 11 September attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. Many other nations have since introduced tougher security and surveillance measures at national entry points as well as stricter immigration procedures. However, the fact remains that Special Permanent Residents are subject to these security measures despite the fact that most in this category are second, third and fourth generation Japan-born residents.

The new system also provides an extension to the period of maximum stay from 3 to 5 years and the introduction of a special re-entry permit. These changes will, in principle, ease the bureaucratic and administrative burden for foreign residents and for the Japanese authorities. The other welcome news is the removal of the term ‘alien’ from the English legal discourse and the use of ‘foreign national’ and ‘resident’ instead. The Japanese term ‘foreigner’ (gaikokujin) remains.

The second main structural change is to the Basic Resident Registration Act. Before the 2012 changes, the jūminhyō reflected the koseki in only applying to Japanese nationals and not to foreign nationals living in Japan. Foreign nationals were already registered through the Alien Registration System, which required them to record any change in residence at the local ward office within 3 months. However, this structure meant that Japanese nationals and non-nationals residing in Japan were divided by separate and distinct registration systems. This administrative demarcation was still applied even when a Japanese national married a non-national (foreign national). There was no formal or consistent recognition that such couples were legally married on either of these two registration systems. As demonstrated in the opening quotes at the beginning of this paper, the children of such families would appear on the koseki and the jūminhyō but not the Alien Registration Certificate. This renders the foreign parent, in the eyes of the bureaucracy at least, as unrelated. Consequently, only a partial picture of families that had members with two or more nationalities was being represented. Different registries handled by different government departments with incomplete information led to numerous impediments and misunderstandings for multinational families. As explained above, some of these impediments included; households being mistaken for single parent families, households where a child was registered as the setai nushi (head of household) because they were the only member of the family registered on the koseki, different procedures in different administrative contexts for different family members, the ‘legitimacy’ of children being question in school and problems over child custody in divorces involving Japanese and non-Japanese nationals (also see Chapman 2008b:435-436).

In 2008 I wrote about a group of foreign residents in Japan who highlighted this issue through protests against a seal that was awarded a ‘special Resident Registration Certificate’ (tokubetsu jūminhyō) (Chapman 2008b). The protesters ‘opposed a registration system that excluded them because of their nationality, despite being long‐term tax‐paying residents’ yet was open to a non‐tax paying fellow ‘mammal’ (Ibid:424). These protests were staged in 2003 and now, almost a decade later, the Japanese government has recognised the problems caused by this approach and has amended the Basic Resident Registration Act so that both Japanese and Foreign nationals will now be registered on the jūminhyō.

According to the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications (2011a) the amendments will enable municipalities to gain a better grasp of multinational families than the previous system allowed. This means that, despite their nationality, all members of a legally recognised family will be identified on one system. In turn, this is meant to eliminate, or at least, significantly reduce the hindrances that such families experienced prior to the change in legislation. This claim is well founded and the change is a welcome step forward for multinational families living in Japan and should alleviate some of the problems encountered under the previous system.

The Broader Context of Residency (Population) Management

These positive developments, however, need to be considered within the broader context of population and residency management. At the centre of legislation in this area is, of course, the koseki and my concerns are mostly with this system. I raise two points for consideration within the context of the 2012 changes. Firstly, I highlight how the idiosyncratic nature of the koseki, in conflating family and nationality, creates numerous irregularities in status that the recent amendments fail to address. Secondly, I argue that these most recent changes also fail to adequately deal with historical legacies that impact on how former colonial subjects and their descendants are documented and identified in Japan.

As outlined above, the changes to the Basic Resident Registration Act allow for the first time, both Japanese nationals and foreign nationals to bureaucratically coexist on one registration system. A multinational family can now register all its family members on the jūminhyō. The change to the Resident Registration that allows multinational families to register on the one system is, as stated above, welcome. However, whilst this change represents progress in the situation for multinational families it stops short of dealing with the more powerful and entrenched koseki seido (Family Registration System) that still administratively and bureaucratically divides families based on nationality.

The administrative format of the koseki and the Resident Registry (jūminhyō) are very similar and in many ways parallel each other. The reason for the existence of such similarities is historical. The koseki registers the ‘principal location of registration’ (honseki) for all Japanese nationals11 that in the past mostly corresponded with birthplace. This is because, in the past, most of the population resided continuously in the ancestral home and thus the honseki and the residential address were one and the same. The jūminhyō is a more recent document and was introduced as the Japanese population become more mobile and urbanised in postwar Japan (White forthcoming). Although the jūminhyō is likely to be used in most daily bureaucratic dealings between multinational families and government departments, there are times in which a koseki tōhon (certified copy) or koseki shōhon (extract) is still required. The fact that family members are still separated according to nationality means that the residency management system still retains the potential to continue to encumber the lives of multinational families. In essence, multinational families are likely to run into the same problems extant under the previous Basic Resident Registration Act in which family members were divided according to nationality.

If we return to the three quotes at the beginning of this paper, we can see how each of these cases may be addressed in some way by the new legislative changes. However, there are still some questions that remain to be answered. For example, in the first case the Chinese woman, and those in similar situations, may still have difficulty if schools continue to prioritize the koseki over the jūminhyō in identifying parents. The same can be said in the third case in verifying marriage status for rental accommodation and in other contexts. It is possible that some government and private organisations will remain unaware of the recent changes and maintain prior practices in which the koseki takes precedence over the jūminhyō. Or, even if aware, some organisations and bodies may choose not to change entrenched practices and request identity to be verified through the koseki. In the second case, the recent legislation will allow all family members to be on one resident registry but the situation of each family member being registered on separate koseki will remain unchanged.

Further, for former colonial subjects and their descendants living in Japan, status as Special Permanent Residents (tokubetsu eijūsha) means a continued ‘denizen’ existence, and in many cases nationality will remain legally obscure. Lara Chen (forthcoming), working with those rendered stateless or with ambiguous status in Japan through the NPO Stateless Network, has discussed how descendants of former colonial subjects (Special Permanent Residents) have their nationalities registered in Japan as, for example, North or South Korean, but in most cases, have no birth certificate.12 In effect, individuals in this situation are rendered stateless and in many cases only realize their stateless status upon applying for a passport to travel overseas. In these cases, instead of a passport, a travel document (tokōsho), a re-entry permit (sainyūkoku kyokasho) and a visa for the country of destination are issued for overseas travel. Moreover, as in the second case introduced in the quotes above, despite being born in Japan, and regardless of generation, for the descendants of former colonial subjects, marriage to a Japanese national brings them no closer to legal status as Japanese. Indeed, having children and creating a ‘family’ actually accentuates the division through the spouse’s exclusion from the koseki whilst every other member of the family is included.

Family Registration Law (kosekihō) and the jus soli approach in Japan as it stands also create difficulties for those that fall into an ‘irregular’ status. This includes so-called Japanese-Filipino Children (JFC) who have not been officially recognized (ninchi) by their Japanese fathers and remain unregistered and consequently excluded from the koseki. This is similar to the situation prior to 1985 when Japanese nationality was patrilineal and children born to American fathers and Japanese mothers were left stateless because the fathers did not declare their paternity.13 Even with the changes in 1985 making nationality ambilineal and the 2008 changes to nationality law,14 the situation for some JFC is still one of exclusion from the koseki and therefore Japanese nationality.

Comparisons

Japan is not the only country with a family registration system. China (hukou), Taiwan (hukou mingbu)15, Korea (hojeok) and Vietnam (ho khau) all have registration systems based on the family as a basic social unit. This is a fundamental bureaucratic and administrative system of population management that differentiates these East Asian countries from the United States and many Western countries. For example, in the US, the UK, Australia and Canada identification of residents is based on the individual as the elementary social unit. The birth certificate is the primary document as proof of identity for obtaining citizenship and, in most cases, for procuring a passport. Most birth certificates contain the names of the mother and father of the registered individual and in principle do not include other family members. Furthermore, a birth certificate is static, in other words, it does not change or require additional information beyond what is first entered at birth. In Japan, the koseki usually lists two generations of family members (if they live under the same roof grandparents may also be included) with updates such as marriages, deaths, adoptions, divorces and acknowledgements of paternity entered as they occur. Therefore it is dynamic and contains far greater detail than a birth certificate. Above all, it is a family rather than an individual record. A new koseki is created once a person marries and the details are then transferred to a new registry.

The other significant difference between Japan and countries like the US is that the latter employ a jus soli approach to citizenship. Thus birthplace is a determining factor in obtaining US citizenship/nationality. Any person born in the US or one of its territories is granted US citizenship regardless of parental citizenship. Children of US citizens are also granted citizenship status. By contrast, Japan applies a mostly jus sanguinis approach that determines nationality according to bloodline. Moreover, Japanese nationality is only granted to those registered on the koseki. Koseki registration is not automatic; parents are required to register their child in the family register in order for that child to be recognised legally as a Japanese national. This means that the koseki is the primary legal mechanism for claiming Japanese nationality and thus complements a bloodline approach to citizenship that is determined by entry into the koseki.16

When it comes to the management of foreign residents, the United States and Japan share some similarities. The US Alien Registration Act (also known as the Smith Act), passed through Congress on 29 June 1940 was motivated by instability in Europe but later was utilised as a vehicle to combat Communism within and outside the US. The introduction of Japan’s Alien Registration Law (gaikokujin tōrokuhō) on 28 April 1952 was motivated by security fears and especially through a connection drawn between the Korean population in Japan and Communism (see Chapman 2008a:25). In the US it is mandatory for visa applicants to submit to fingerprinting as part of biometric identification. Although fingerprinting is used in a number of countries it is worth noting that Japan did not have a history of fingerprinting before the introduction of the Alien Registration Law. The connection between the immigration and alien registration laws in both the US and Japan can be understood in part in light of a deep-rooted fear of communism in the US and the postwar influence of the SCAP administration on Alien Registration Legislation and Immigration Laws in Japan.

The US, of course, has no colonial legacy in which former colonial subjects are classified according to a different visa status. However, the US does have ‘insular areas’ that differ from US states. Insular areas such as the US Virgin Islands, Guam, Puerto Rico and American Samoa are US territories but are differentiated from the 50 states or the District of Columbia. Voting rights in these areas differ from those of the states in that residents do not have voting representation in the congress and are not entitled to electoral votes for President. Although not constitutionally eligible for US citizenship, residents of all territories, with the exception of American Samoa, have had citizenship rights extended to their inhabitants. The inhabitants of these territories are nevertheless legally distinct and are not US citizens or US nationals.

The US and Japan do share a historical parallel with the use of census data. During the Second World War the US Census Bureau handed over census data to the Justice Department, Secret Service and other agencies to identify Japanese-Americans. This resulted in the internment of over 120,000 first generation (issei) and second generation (nisei) (El Nasser 2007; also see Ng 2002). Although a very different context, there are some parallels here with Japan’s use of family registration data to identify Koreans and Taiwanese in postwar Japan.

Criticism

As mentioned, other Asian countries have family registration systems. South Korea has introduced legislative changes to address concerns raised over a family-based system of registration. In 2005, amendments to South Korea’s Civil Code eliminated the family head system (hojeok). The Law on the Registration of Family Relationships was enacted on 1 January 2008 and will eventually turn the family law system into an individual registration system. As an individualized system of documentation these changes will lead to the elimination of the disparities occurring under a family-based system like that in Japan. It was a result of lobbying by women’s groups and civil liberty organisations in Korea concerned about the human rights violations occurring under the system that led to change. Normally, individual registration does not create the encumbrances and marginalization that family registration does when identifying members of a nation (for more on this see Mackie 2009).17 Individual registration eliminates the need for defining residents according to their position in relation to state determined and registered households.

There have been numerous advocates for change in Japan’s Family Registration System. Calls for reform have come from many quarters of society not just those representing foreign residents. Many of these critics have stressed the benefits of an individualised form of registration that would alleviate the discrimination created by the koseki (see Fukushima, 2001; Ninomiya, 2006: 24; Kitamura, 2001; also see Miyamoto, Ninomiya and Shin 2011). For example, freelance writer Kitamura Toshiko (2001) has questioned the need for maintaining the family register (koseki戸籍), suggesting that it be replaced with an individual register (koseki個籍).18 Her argument stems from the fact that the koseki is based on a patriarchal approach to family and discriminates against children born out of wedlock.19 Similarly, Fukushima Mizuho (2001) sees the limitations placed by the state through the koseki law on what constitutes a family. Ninomiya Shūhei, a law academic well known for his criticism of a family-based registry that discriminates on many levels especially in the area of Gender Identity Disorder (GID) and sexual identity, also calls for a registration system based on the individual (2006: 24). However, despite these recent calls for change, family registration and family law have undergone little change in Japan.

Conclusion

In conclusion, there are two points that I wish to emphasize. The first is the need to recognise the positive steps in abolishing the Alien Registration Law and the creation of a new residency management system that allows all members of multinational families to be identified and documented together on one register. This has the potential to alleviate many administrative problems encountered under the former system. The replacement of the term ‘alien’ with ‘foreign resident’ is also a welcome advance, as is the lifting of the requirement for foreigners to apply for re-entry permits whenever leaving Japan. These are signs that Japan recognises the changing landscape of its society and the necessity for broad administrative change to improve the lives of its foreign and Japanese residents.

The second point I wish to make is one of caution. As I have highlighted, there remain unnecessary barriers created by the koseki system as part of Japan’s overall residency (population) management system. Despite the progress in the new management system, multinational families are still divided into nationals and non-nationals through the koseki and this will continue as long as Japanese nationality is determined by family registration. In this respect, the impact of the change in the new residency management system is still unclear and will be determined by practices at the local level by both government and private organisations. This brings me to a broader concern with the koseki system, which is that real change in the management of residents (Japanese nationals and non-nationals alike) will not be evident until the role of the Family Registration System in determining Japanese nationality is reconsidered.

A register that defines legal status as a Japanese national through a family-based registration system affects the lives of many residents in Japan in diverse and unexpected ways and often encumbers people’s lives without their full realisation. The modern koseki began as a bureaucratic instrument of systemization and a mechanism of state security. Moreover, its inception was at a time when international legal codes and the Western notion of nationality had not been established in Japan. Despite this, the system has changed little over time. In contemporary Japan this form of population management is anachronistic and has failed to recognise and follow social change resulting in the creation of unnecessary borders and boundaries that are progressively detrimental to a changing society in an increasingly globalised and connected world.

David Chapman is the convenor of Japanese studies at the University of South Australia. His present research interests focus on the history of minority communities in Japan. He is the author of Zainichi Korean Identity and Ethnicity published by Routledge. He is presently working on two projects involving a social history of identification in Japan and the life stories of first settler descendants on the Ogasawara Islands.

This is an adaptation of a chapter forthcoming in Tai Wei Lim and Stephen Nagy, eds., “Demography and Migration”, The Edwin Mellen Press.

Recommended citation: David Chapman, “No More ‘Aliens’: Managing the Familiar and the Unfamiliar in Japan,” Vol 10 Issue 40 No. 3, October 1, 2012.

Articles on related subjects

• David Chapman, Geographies of Self and Other: Mapping Japan through the Koseki

• Miyamoto Yuki, Ninomiya Shohei and Shin Kyon, The Family, Koseki, and the Individual: Japanese and Korean Experiences

• Tessa Morris-Suzuki, Exodus to North Korea Revisited: Japan, North Korea, and the ICRC in the “Repatriation” of Ethnic Koreans from Japan

• Tessa Morris-Suzuki, Guarding the Borders of Japan: Occupation, Korean War and Frontier Controls

• Lawrence Repeta and Glenda S. Roberts, Immigrants or Temporary Workers? A Visionary Call for a “Japanese-style Immigration Nation”

• Gracia Liu-Farrer, Debt, Networks and Reciprocity: Undocumented Migration from Fujian to Japan

• Tessa Morris-Suzuki, Migrants, Subjects, Citizens: Comparative Perspectives on Nationality in the Prewar Japanese Empire

• Arudou Debito & Higuchi Akira, Handbook for Newcomers, Migrants, and Immigrants to Japan

• Glenda S. Roberts, Labor Migration to Japan: Comparative Perspectives on Demography and the Sense of Crisis

• Sakanaka Hidenori, The Future of Japan’s Immigration Policy: a battle diary

• Tessa Morris-Suzuki, Invisible Immigrants: Undocumented Migration and Border Controls in Early Postwar Japan

References

Chapman, David. 2008a. Zainichi Korean Identity and Ethnicity, Routledge, London.

Chapman, David. 2008b. Tama Chan and Sealing Japanese identity, Critical Asian Studies, Vol. 40, No. 3, pp. 423 – 443.

Chapman, David. 2011. Geographies of self and other: Mapping Japan through the koseki, The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol 9, Issue 29 No 2, July 18.

Chen, Tien-shi (Lara). 2010. ‘Kokka to kojin o tsunagu mono no shinsō’ [The truth behind what connects the state and the individual] in Chen Tien-shi, Kondō Atsushi, Komori Hiromi and Sasaki Teru (eds), Ekkyō to aidentifikeeshon [Identification and Crossing Borders), Tokyo: Shinyōsha, pp. 444-468.

Chen, Tien-shi (Lara). 2011. Mukokuseki [Stateless], Tokyo: Shinchō Bunko.

Chen, Tien-shi (Lara). forthcoming. ‘Legally invisible: Mukoseki and mukokuseki’ in Chapman, D. and Krogness, K. J. eds. People, Power and Polity: Household Registration and the Japanese State, London: Routledge.

El Nasser, H. Papers show census role in WWII camps, USA Today, accessed 25 Sept 2012 here.

Endō, Masataka. 2010. Kindai Nihon no shokuminchi tōchi ni okeru kokuseki to koseki: Manshū, Chōsen, Taiwan [Nationality and Family Registration within Modern Japan’s Colonial Territories: Manchuria, Korea and Taiwan], Tokyo: Akashi Shoten.

Fukushima, Mizuho (ed). 2001. Are mo kazoku kore mo kazoku: Ko o daiji ni suru shakai e [That is Family, That is also Family: Towards a Society that Values the Individual], Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten.

Hertog, Ekaterina. 2009. Tough Choices: Bearing an Illegitimate Child in Contemporary Japan Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Kitamura Toshiko. 2001. ‘Koseki kara koseki e’ [From family registration to individual registration] in Fukushima Mizuho (ed) Are mo kazoku kore mo kazoku: Ko o daiji ni suru shakai e [That is Family, This is also Family: Towards a Society that Values the Individual], Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten.

Mackie, V. 2009. ‘Family law and its others’ in Scheiber, H. and Mayali, L, eds, Japanese Family Law in Comparative Perspective, Berkeley: The Robbins Collection, 139-64.

Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications (Sōmushō). 2011a. Changes to the Basic Resident Registration Law: Foreign residents will be subject to the Basic Resident Registration Law, accessed 9 August 2012.

Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications (Sōmushō). 2011b. Marriages by nationality of bride and groom: Japan, each prefecture and 20 major cities, accessed 24 Sept 2012 here.

Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications (Sōmushō). 2011c. Vital Statistics in Japan: The latest trends, accessed 24 September.

Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications (Sōmushō). Undated. Start of a new residency management system, accessed 9 August 2012 here.

Miyamoto Yuki, Ninomiya Shuhei, and Shin Ki-young. 2011. The family, koseki, and the individual: Japanese and Korean experiences, The Asia-Pacific Journal Vol 9, Issue 36 No 1, September 5.

Morris-Suzuki, T. 2011. Guarding the borders of Japan: Occupation, Korean war and frontier controls, The Asia-Pacific Journal Vol 9, Issue 8 No 3, February 21.

Nagano, Takeshi, Zainichi Chūgokujin: Rekishi to aidentiti [Zainichi Chinese: History and Identity], Tokyo: Akashi Shoten.

Ng, W. 2002. Japanese American Internment During World War II: A History and Reference Guide, Westport: Greenwood Press.

Ninomiya, Shūhei. 2006. Koseki to Jinken [The Koseki and Human Rights], Tokyo: Kaihō Shuppansha.

Ryang, S. 1997. North Koreans in Japan: Language, Ideology, and Identity, Colorado: Westview Press.

Swenson, T. undated. Japan’s family registry system international marriages face a policy of exclusion, accessed 10 September 2012.

Vasishth, A. 1997. ‘A model minority: The Chinese community in Japan’, in Japan’s Minorities: The Illusion of Homogeneity, Michael Weiner (ed), London: Routledge.

White, Linda. (forthcoming). ‘Challenging the heteronormative family in the koseki: Surname, legitimacy, and unmarried mothers’ in Chapman, D. and Krogness, K. J. eds. The State and Social Control: Citizenship and Japan’s Household Registration System, London: Routledge.

Notes

1 This situation is likely to have occurred because the woman is Korean and therefore not registered on her Japanese husband’s koseki register. The koseki is the primary legal form of identification and proof of status for Japanese nationals.

2 I will use the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications (Sōmushō) definition of ‘multinational family’ throughout this paper. That is, families which contain a member with a foreign nationality and at least one member who is a Japanese national.

3 In 2011 international marriages accounted for around 6 % of all marriages in Tokyo and 3.9% of all marriages in Japan (Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare 2011b). International marriages in Japan have been in decline since their peak in 2006 but still represent a significant number (Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare 2011c:32).

4 Japan does not recognise dual or multiple nationality.

5 Often the status of colonial subjects is described as Japanese ‘nationality’. Although the term kokumin (often defined as ‘national’ in the modern context) is used to define colonials during this period, I prefer to refer to refer to ‘Japanese legal status’. This is because the rights and obligations of colonial subjects from those of nai’chi registered Japanese subjects (nationals). For example, whilst Koreans in Japan had the right to vote, those in the outer territories did not. This can be thought of as a ‘layered or differential citizenship’. Furthermore, Japan’s Nationality Law was never implemented on the Korean peninsula and it was the Family Registration Law (kosekihō), not the Nationality Law (kokusekihō), that determined ‘nationality’ or who was a kokumin (Endō 2010:18-19).

6 Ryūkyūans were also considered ‘non-Japanese’ and expected to repatriate to their southern island homes. After the 1972 return of Okinawa to Japan however, Okinawans gained full rights as nationals and citizens of Japan.

7 This Order was full of inconsistencies in the way it defined ‘aliens’. Many without legal status as Japanese; Allied Forces personnel, SCAP members and employees and their families, people in Japan on official business and their accompanying staff and families (Article 2) were not considered ‘aliens’. However, former Taiwanese and Korean colonial subjects were to be considered ‘aliens’ even though they possessed Japanese legal status (Article 11).

8 The San Francisco Peace Treaty, promulgated on the same day, renounced the sovereign control of Japan over the territories of Korea, Taiwan, Karafuto and territories south of 30 degrees north latitude.

9 By this time many of the Koreans and Taiwanese colonial subjects living in Japan had returned to their respective homelands.

10 The alien registration and immigration laws introduced into Japan during the post-war period were significantly influenced by SCAP directives and a US obsession with Cold War communism and border control.

11 Foreign residents when registered also have their honseki recorded. In most cases this is the country corresponding to their nationality.

12 In Japan birth is registered on the koseki but this is only possible if at least one parent is a Japanese national.

13 Most cases were isolated to Okinawa where there are many US military bases.

14 On 4 June 2008 the Supreme Court amended the Nationality Law which resulted in a revision to Article 3 (revised 12 December 2008 and introduced 1 January 2009). The change states that, providing fathers recognise paternity, regardless of the timing, children born out of wedlock will be able to obtain Japanese citizenship (see Chapman 2011).

15 Information provided by Toni Chen for the term used in Taiwan.

16 Entry into the koseki is also possible through marriage and adoption.

17 Mackie highlights the many ways the Family Registration System marginalises the population in Japan (2009).

18 With a play on words, the Japanese character for individual ‘ko’ which has the same reading as the character used for the household in the term koseki, rendering the reading for both a family register and an individual register as ‘koseki’.

19 Children born out of wedlock (this includes in many cases children resulting from long term de facto relationships) were identifiable by the character ‘ko’ (子)being placed by their name and the lack of indication of birth order of the child. The law was changed and since 2004 all children born in Japan have been designated as simply boy or girl and birth order has been removed. However, ‘illegitimacy’ is still recognisable by checking if the father’s name is recorded or if the couple were married at the time of birth on the koseki (see also White forthcoming and Hertog 2009).